Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, social isolation, especially among university students, was a significant problem due to limited campus visits. This social environment could influence COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy because of a lack of accurate information or fear of novel behaviors resulting from loneliness. This study examined the association of social isolation and loneliness with vaccine hesitancy among university students in Tokyo. An online questionnaire was administered to all students at the Union of Four Universities in Tokyo in March 2022. Respondents were asked about their vaccination frequency, social isolation, loneliness, and other covariates including mental health. Vaccine hesitant were defined as those who had never been vaccinated or had been vaccinated only once during the third vaccination period. Logistic regression analysis was performed. Of the 2,907 students, 1,080 (37.2%) were socially isolated, 480 (16.5%) felt lonely and 113 (3.9%) were vaccine hesitant. Lonely students hesitated vaccine 2.08 times more than non-lonely students (95% CI: 1.25–3.44), which was not true for social isolation (OR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.69–1.65). Loneliness, but not social isolation, was associated with vaccine hesitancy among university students in Tokyo. These findings can be used to plan vaccination programs for adolescents and young adults against future pandemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a respiratory infection caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which has caused a pandemic with serious health, economic and social consequences worldwide1. In addition to preventing infection through behavioral restrictions or the use of masks, the most effective way to control this pandemic is to achieve mass immunity through COVID-19 vaccination2. While COVID-19 vaccination is being promoted, vaccine hesitancy, defined as “delaying or refusing vaccination despite the availability of vaccination services”, is a major challenge worldwide.

A nationwide survey of individuals aged 20–74 on July 21–23, 2021, when the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine was fully administered to healthy individuals aged 18 years and older in Japan, showed that about 30% of the 5,000 participants were hesitant to receive COVID-19 vaccine3. According to the Prime Minister’s Office of Japan, as of March 10, 2022, the vaccination rates were as follows: first dose coverage was 80.4% for the entire population, second dose coverage was 79.3%, and third dose coverage was 28.3%4. For the elderly population aged 65 years and older, the first dose coverage was 92.7%, the second was 92.4%, and the third was 67.4%4. On the other hand, in Tokyo, where hot spot of COVID-19 pandemic and age-specific data are available, the first dose coverage for individuals in their 20s was 79.2%, the second dose coverage was 78.1%, and the third dose coverage was 11.5% 4, lower than average. To expand immunization programs, especially among younger age groups, it is important to understand the factors that influence their vaccine uptake.

Various possible factors have been identified as influencing vaccine hesitancy, including trust issues (not trusting the vaccine or provider), complacency issues (not feeling the need for or the value of the vaccine), and convenience issues (access)5. While these concepts are useful in explaining vaccine hesitancy, they are not sufficient to explain why individuals arrive at this epistemological position, that is, why they do not trust the vaccine, why they do not feel the need for it, and why they do not overcome the difficulties of accessing the vaccine. According to studies on individuals’ reluctance to vaccinate, there are several psychological characteristics (e.g., depression and anxiety) that may influence individuals’ perceptions and attitudes6,7, which can be determined by human relationships, such as social isolation, or loneliness8,9,10. Young adulthood, or emerging adulthood11 is a critical and transitional period that presents psychosocial challenges, such as striving for independence, increased responsibilities, moving away from family relationships, and gravitating towards peer-based relationships12. This stage is also susceptible to loneliness13. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the issue of social isolation and loneliness among university students, as they are restricted or discouraged from going out, and online lectures (including on-time and on-demand) were provided immediately for most classes14. Thus, we hypothesize that social isolation or loneliness may be one of the root causes of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among university students.

Social isolation and loneliness look similar, but they are different. Social isolation is defined as an inadequate quality and quantity of social relationships with others. It is primarily judged objectively, whereas loneliness is a distressing, subjective emotional state resulting from a discrepancy between desired and achieved patterns of social interaction15. A study of 22,756 participants aged 15–81 from across Japan revealed that vaccination rates were lower among those who were socially isolated. They did not have negative perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine but were less likely to receive information from those who had been vaccinated16. Another previous study reported that loneliness was associated with a subsequent decrease in influenza vaccination among individuals over 60 years of age in Germany, possibly because lonely individuals may not perceive the use of preventive health services as a social norm or may lack motivation to use the services17. Another study examined the association between loneliness and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in adults in the United Kingdom and found that lonely individuals tended to have lower risk estimates for COVID-19 and were less likely to be vaccinated against COVID-1918. The findings of these previous studies suggest that both socially isolated and lonely individuals are less likely to gather information and use preventive health services and have lower vaccination rates.

Vaccine hesitancy needs to be considered in a cultural context. Previous studies on vaccine hesitancy have been conducted mainly in Western countries where individualism is more prevalent19,20, but in Japan, which has a collectivist culture21,22,23,24,25, the impact of social isolation and loneliness on attitudes toward vaccines may be different. It would be interesting to conduct a study that examines the association of social isolation and loneliness with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Japan, as the negative effects of these psychosocial factors may be more pronounced in environments with strong peer pressure and homogeneity among university students.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the association of social isolation and loneliness with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Japanese university students. In addition, by analyzing the association between these psychosocial factors and the reasons for vaccine hesitancy, we attempted to contribute to the formulation of more effective vaccine promotion measures.

Methods

Design, setting, and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted in March 2022, after the first but before the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. All students at the Union of Four Universities in Tokyo (Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Tokyo Institute of Technology, and Hitotsubashi University) were informed about the survey, and an online questionnaire was administered. The questionnaire was anonymous, and responses were received from 2935 students. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Of these, 2907 were finally included in the analysis after excluding samples that did not respond to the study outcome “vaccine hesitancy” (n = 6), as well as those that did not provide information on gender (n = 22, because the sample size of this cell is too small to analyze). This study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee at Tokyo Medical and Dental University (approval ID: M2021-299).

Social isolation and loneliness

For social isolation, students were asked, “In the past year, how many friends do you see at least once a week?” and if they answered “0”, they were considered to be socially isolated (definition 1). This was based on the assumption that students met their friends in person, but some respondents may have included online interactions through online meeting tools. In this study, we did not explicitly exclude online interaction in the survey due to the difficulty of distinguishing in-person and online social connectedness between the students under the COVID-19 circumstance. For the sensitivity analysis, we also defined social isolation as having no friends to meet at least once a week in the past year and living alone (definition 2). Loneliness was measured using the 10-item UCLA Loneliness Scale Version 3 (Japanese version)26,27. The scores ranged from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater loneliness. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current population was 0.87. Based on the cutoff for loneliness in the previous study28 and the finding that 20% of participants in Japan reported occasional or more frequent loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic29, we considered a participant to be lonely if the loneliness score was above the 80th percentile, i.e., the score was equal to or over 27.

Vaccine hesitancy

Vaccine hesitancy is generally defined as a delay in accepting or refusing a vaccine despite the availability of vaccine services5. In this study, vaccine hesitant was defined as those who had never been vaccinated or had been vaccinated only once during the third vaccination period, because the survey was conducted at the time when the third vaccination was in full swing in Japan.

Covariates

Covariates included age, sex, university affiliation, economic situation (stable, moderate, tight), living arrangements (whether living alone or not), physical health score (self-assessed on an 11-point scale from 0 “poor” to 10 “good”), and mental health score (self-assessed on an 11-point scale from 0 “poor” to 10 “good”). Previous study has shown that these covariates influence both social isolation/loneliness30 and vaccine hesitancy31. They were assessed through the questionnaire. Missing values for covariates ranged from 0% for sex to 7.3% for social isolation (n = 211), and imputed datasets were created in Stata using mi impute32. 50 imputed datasets were obtained. The results from each imputed dataset were aggregated into one estimate using Rubin’s rule33.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are reported as frequencies (%) and continuous variables as means (SD: standard deviation). To compare variables between different groups, the chi-squared test was used for categorical variables, and ANOVA was used for continuous variables. The primary outcome of this study was vaccine hesitancy. First, a univariable logistic regression analysis was performed to determine whether social isolation or loneliness was associated with vaccine hesitancy. Subsequently, a multivariable analysis was performed adjusting for the above covariates. To further assess the robustness of our findings, we changed the definition of social isolation from definition 1 to definition 2 and conducted a sensitivity analysis to verify the stability of the results. As a secondary analysis, a multivariate logistic regression analysis of model 3 was conducted to examine the interaction between social isolation (definition 1)/loneliness and each covariate (economic status and living environment). To assess the association between social isolation (definition 1) and loneliness, we also presented the distribution of social isolation and loneliness among participants and then conducted an independence chi-squared test using the supplemented data set. Data analysis was performed with Stata 15.0 SE (Stata Corporation, Texas, TX). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. Of the 2,907 participants, 1080 (37.2%) were socially isolated (definition 1) and 480 (16.5%) felt lonely. Of the 113 who hesitated to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, 31 (27.4%) felt lonely. On the other hand, of the 2,794 who did not hesitate to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, a smaller percentage of them (449, 16.1%) felt lonely. There were no differences in mean age (22.7 years [SD: 4.9] and 23.1 years [SD: 5.2], respectively) or sex ratio (male: 66.4% and 57.6%, respectively) between the vaccine hesitant and non-hesitant groups. The distribution of university affiliation did not differ either. In terms of economic situation, 50–60% of the students were stable and there was no difference in the distribution between the two groups. However, the percentage of students living alone was higher in the vaccine hesitant group (49.6% vs. 36.8%).

The odds ratio (OR) of social isolation (definition 1) and loneliness for vaccine hesitancy is shown in Table 2. After adjustment for covariates, model 1 showed that social isolation was not associated with vaccine hesitancy (OR: 1.20, 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 0.79–1.83). On the other hand, model 2 showed that loneliness approximately twofold increased risk of vaccine hesitancy (OR: 2.12, 95% CI: 1.29–3.46). Finally, in model 3 where social isolation and loneliness were put into the model simultaneously and adjusted for covariates, social isolation was not associated with vaccine hesitancy (OR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.69–1.65), but loneliness was still associated with vaccine hesitancy (OR: 2.08, 95% CI: 1.25–3.44). There was no statistically significant interaction between social isolation/loneliness and each covariate (economic situation, living arrangements). Table S2 in the Supplementary Information shows the results of the sensitivity analysis. When we changed the definition of social isolation from definition 1 to definition 2 and analyzed the same models, the results were all similar in trend. In model 3, social isolation was not associated with vaccine hesitancy (OR: 1.47, 95% CI: 0.87–2.48), but loneliness was still associated with vaccine hesitancy (OR: 2.08, 95% CI: 1.27–3.41).

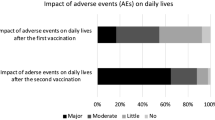

The status of social isolation (definition 1) and loneliness is shown in Table 3. Of the total, 10.4% of the students were socially isolated and lonely. 26.6% had only social isolation, and 5.3% of the students had only loneliness. The results of a chi-square test of independence indicated a small, positive association between social isolation and loneliness (χ2 (1) = 8500, p < 0.001, N = 148027, φ = 0.24). The results of a question on the reasons for beliefs about future vaccination intentions are shown in Table 4. Both socially isolated (definition 1) and lonely individuals were less likely to be recommended for vaccination by family and friends and less likely to be concerned about infecting others. Socially isolated individuals were not likely to underestimate COVID-19 or take adverse events more seriously. Conversely, lonely individuals were less concerned about serious illness. They were more worried about adverse reactions, with some believing that a foreign body would enter their bodies due to vaccination.

Discussion

In this study, we found that loneliness was an independent risk factor for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Japanese university students, whereas social isolation was not. This suggests that the emotional state of experiencing loneliness is a more important determinant of vaccine hesitancy than the structural social network of being socially isolated among university students.

This finding is consistent with a previous study conducted in the United Kingdom, which showed a negative association between loneliness and the likelihood of receiving the COVID-19 vaccine18. Another study of participants aged 15–81, with almost equal representation of all age groups across Japan, found that social isolation, but not loneliness, was associated with vaccine hesitancy16. In the study, the following differences between social isolation and loneliness were indicated as contributing factors: socially isolated individuals tended to receive less information about vaccination from family and surroundings and to estimate their own low risk of severe illness, whereas lonely individuals gathered information but were afraid of adverse events. On the other hand, in our study, information about vaccination from family and community was less common among both socially isolated and lonely individuals, and optimism about severe illness and fear of adverse events was higher among lonely individuals. According to the 2021 Communications Usage Trend Survey conducted by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications34, the Internet usage rate in Tokyo is 87.0% (compared with the national average of 82.9%), of which the social networking service usage rate is 79.4% (compared with the national average of 72.19%), which is higher. In Tokyo, a large metropolitan area, the psychological impact of loneliness is estimated to be greater than the amount of information problems caused by social isolation. Besides, that previous study defined vaccine hesitant as those who had never been vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine in February 2022, while our study defined vaccine hesitant in March 2022 as those who had never been vaccinated or had been vaccinated only once during the third vaccination period (i.e. a relatively lax definition of vaccine hesitant). Further, in that previous study, social isolation was assessed according to the Lubben Social Network Scale 6 (Japanese version)35, which asked about family relationships and friendships. Whereas we defined social isolation as “not getting together with friends at least once a week in the past year”. Loneliness was assessed using the 3-item version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale Version 3 (Japanese version)26 in the previous study and the 10-item version in our study. As a result, in the previous study, 56.8% of 15-44-year-olds were socially isolated (of whom 18.1% were vaccine hesitant) and 43.4% were lonely (of whom 15.5% were vaccine hesitant). In contrast, our study showed a lower prevalence of loneliness by using a 10-item version; 37.2% were socially isolated (of whom 3.9% were vaccine hesitant) and 16.5% were lonely (of whom 6.5% were vaccine hesitant). In addition to differences in prevalence in the study population, the fact that our study did not include relationships with family members or advisers in the assessment of social isolation may have influenced the differences in results.

Loneliness may contribute to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for the following three reasons. First, lonely individuals may be less able to access and use information about COVID-19; a survey of young Australian adults during the COVID-19 pandemic found that loneliness, but not social isolation, was associated with lower health literacy36. Individuals experiencing higher levels of loneliness reported less social support for their health and had more difficulty finding, evaluating, and understanding medical information. This may be due to negative feelings about themselves and others, making it difficult for them to find trustworthy people and information in the first place12. Second, it may be associated with less contact with communities with positive social norms about prevention that can be shared and reinforced among community members, which may lead to less interest in prevention activities. For example, according to an earlier study of COVID-19 preventive behaviors and loneliness in Japanese adults, loneliness was associated with lower engagement in personal preventive behaviors such as wearing masks, washing hands, and keeping a social distance when outdoors37. High levels of loneliness have also been associated with lower uptake of preventive health services, including cancer screening38,39,40. Third, individuals experiencing loneliness often overestimate their own risk (in this case, the risk associated with vaccination)41. Lonely individuals have been reported to attend preferentially to negative social information, to have reduced neural responses to pleasant social stimuli, and to have increased neural activation when viewing unpleasant social images. These findings support the hypervigilance to social threat hypothesis (HSTH) for loneliness42. As a result, they may evaluate vaccines negatively and choose not to be vaccinated.

We also examined the interactions between social isolation/loneliness and several key covariates (economic situation, living arrangements) using multivariate logistic regression. Although none of these interactions reached statistical significance, this does not rule out the possibility that these factors may still influence vaccine hesitancy, either individually or in combination. These covariates could potentially influence vaccine hesitancy through pathways not captured by our interaction analysis, such as by directly influencing access to information or health care resources.

Social isolation and loneliness are moderately correlated with each other, but they are distinct psychosocial constructs in the previous study43. This means that socially isolated individuals do not necessarily experience loneliness, and conversely, some individuals may experience loneliness without being socially isolated. It can be assumed that individuals who are socially isolated but not lonely may have a low preference for social relationships, low expectations of social relationships and contact, and a reserved personality that does not want much from others44,45,46. In contrast, individuals who are not socially isolated but lonely may be dissatisfied with their existing relationships due to factors such as having low-quality or toxic relationships, and having different expectations and preferences for relationships from their existing ones45,47,48,49. In this study, a small positive correlation was found between social isolation and loneliness; 71.5% of those who were socially isolated were not lonely, and 9.5% of those who were not socially isolated experienced loneliness. During the COVID-19 pandemic, even in an environment that encouraged social distance and less social behavior, students may have remained socially connected and interacted with family and friends through online channels. One limitation is that our assessment of social isolation (“In the past year, how many friends do you see at least once a week?“) may have included online interaction. Future study should distinguish between in-person and online interaction for a more accurate understanding of social connectedness. In addition, Japan had a social norm that encouraged social isolation for the public benefit22,23. It is also possible that they recognized that being socially isolated was the same situation as everyone else and that they were not unique, and were, therefore, less likely to experience negative emotions. Further study investigating the impact of social isolation and loneliness on health outcomes is warranted, taking into account the similarities and differences between these psychosocial factors.

This study has several limitations. First, the data in this study are cross-sectional, so the direction of association or causality cannot be determined. While an association between social isolation/loneliness and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is suggested, it is possible that students who did not receive the COVID-19 vaccine felt lonely due to less socially acceptable behaviors associated with their decision. Longitudinal studies are needed to clarify the temporal order and causality between these factors. Second, there are other unmeasured factors that may confound the observed association. Specifically, in addition to political beliefs and distrust of health care providers, the lack of digital health literacy and the spread of misinformation need to be considered. Recent studies have suggested that individuals with lower digital health literacy are more susceptible to misinformation and that the spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories about COVID-19 vaccines through social media significantly influences attitudes and vaccination rates50,51. Third, an exact response rate was not available because the survey was distributed through university registered mail for students and the number of invitees was unknown to the researchers. Students who chose to participate in the study may have been systematically different from those who did not. Future study examining the characteristics of non-respondents is warranted to assess the potential impact of selection bias. Fourth, the study participants were students from the four universities, a population with a relatively high level of education. Previous studies have shown that individuals with lower levels of education are more likely to be lonely52 and avoid to vaccines53,54. The results of this study may underestimate the true association between loneliness and vaccine hesitancy. Furthermore, vaccine hesitancy varies by region, and it is known that vaccination rates tend to be lower in rural areas than in urban areas55, so the impact of these factors should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. This limits the generalizability of our findings to other populations and contexts. Future study should include a more diverse sample of students from different universities and regions to improve external validity.

Nonetheless, the results of this study have important implications for university student vaccination programs for future pandemics. Addressing the loneliness of this population is one strategy to reduce vaccine hesitancy. This can be achieved through neighborhood identification and the formation of stronger social networks56,57,58. For example, being active on the university campus, engaging with peers, and interacting with faculty members can increase a sense of belonging to one’s university59,60. Higher levels of loneliness are reported by students in departments with small group sizes or where self-study and writing are more common61. Therefore, incorporating more collaborative learning with peers and teachers into the curriculum may help to reduce loneliness62. It is also known that support, particularly from friends, has been found to reduce loneliness63, and social support groups set up by universities may be a useful tool for discussing potential problems and making contact with others64. Furthermore, university students who are less physically active are more likely to be lonely, and the provision of university sports programs can help to increase the proportion of physically active students65. When planning vaccination programs for adolescents and young adults in future pandemics, it may be helpful to include loneliness interventions. Future study should also evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions in improving vaccine uptake and reducing loneliness among university students.

Conclusion

Loneliness was associated with vaccine hesitancy but not with social isolation among university students in Tokyo. This suggests that measures to address loneliness should be considered when planning vaccination programs for adolescents and young adults in future pandemics.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19 (2020).

Bartsch, S. M. et al. Vaccine efficacy needed for a COVID-19 coronavirus vaccine to prevent or stop an epidemic as the sole intervention. Am. J. Prev. Med. 59, 493–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.011 (2020).

Okamoto, S., Kamimura, K. & Komamura, K. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and vaccine passports: A cross-sectional conjoint experiment in Japan. BMJ Open 12, e060829. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-060829 (2022).

The 76th Advisory Board on Countermeasures to Combat New Coronavirus Infections. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000913223.pdf (2022).

MacDonald, N. E. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 33, 4161–4164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036 (2015).

Nomura, S. et al. Reasons for being unsure or unwilling regarding intention to take COVID-19 vaccine among Japanese people: A large cross-sectional National survey. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 14, 100223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100223 (2021).

Tsutsumi, S. et al. Willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccination and the psychological state of Japanese university students: A Cross-Sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031654 (2022).

Giovenco, D. et al. Social isolation and psychological distress among Southern U.S. College students in the era of COVID-19. PloS One 17, e0279485. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279485 (2022).

Matthews, T. et al. Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: A behavioural genetic analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 51, 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1178-7 (2016).

Ray, M. E., Coon, J. M., Al-Jumaili, A. A. & Fullerton, M. Quantitative and qualitative factors associated with social isolation among graduate and professional health science students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 83, 6983. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe6983 (2019).

Arnett, J. J. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 55, 469–480 (2000).

Heinrich, L. M. & Gullone, E. The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 26, 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002 (2006).

Varga, T. V. et al. Loneliness, worries, anxiety, and precautionary behaviours in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal analysis of 200,000 Western and Northern Europeans. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2, 100020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100020 (2021).

Information and Communications in Japan. WHITE PAPER 2021. https://www.soumu.go.jp/johotsusintokei/whitepaper/eng/WP2021/chapter-2.pdf#page=4 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Social isolation in mental health: A conceptual and methodological review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 52, 1451–1461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1446-1 (2017).

Ukai, T. & Tabuchi, T. Association between social isolation and loneliness with COVID-19 vaccine uptake in Japan: A nationwide cross-sectional internet survey. BMJ Open 13, e073008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-073008 (2023).

Hajek, A. & König, H. H. Does loneliness predict subsequent use of flu vaccination? Findings from a nationally representative study of older adults in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244978 (2019).

Jaspal, R. & Breakwell, G. M. Social support, perceived risk and the likelihood of COVID-19 testing and vaccination: Cross-sectional data from the united Kingdom. Curr. Psychol. 41, 492–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01681-z (2022).

Hofstede, G. Culture and organizations. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 10, 15–41 (1980).

Jiang, S., Wei, Q. & Zhang, L. Individualism versus collectivism and the early-stage transmission of COVID-19. Soc. Indic. Res. 164, 791–821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02972-z (2022).

Kokami Shoji, N. S. Peer pressure (Dotyo Atsuryoku) (Kodansha, 2020).

Lu, C., Menju, T. & Williams, M. Japan and the other: Reconceiving Japanese citizenship in the era of globalization. Asian Perspect. 29, 99–134. https://doi.org/10.1353/apr.2005.0030 (2005).

Fukushima, M., Sharp, S. F. & Kobayashi, E. Bond to society, collectivism, and conformity: A comparative study of Japanese and American college students. Deviant Behav. 30, 434–466 (2009).

Asai, A., Okita, T. & Bito, S. Discussions on present Japanese psychocultural-social tendencies as obstacles to clinical shared decision-making in Japan. Asian Bioeth. Rev. 14, 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41649-021-00201-2 (2022).

Vogt, G. & Qin, S. Sanitizing the National body: COVID-19 and the revival of Japan’s closed country strategy. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 31, 247–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/01171968221125482 (2022).

Arimoto, A. & Tadaka, E. Reliability and validity of Japanese versions of the UCLA loneliness scale version 3 for use among mothers with infants and toddlers: A cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 19, 105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0792-4 (2019).

Russell, D. W. UCLA loneliness scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 66, 20–40. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2 (1996).

Koyama, Y. et al. Interplay between social isolation and loneliness and chronic systemic inflammation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: Results from U-CORONA study. Brain Behav. Immun. 94, 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.03.007 (2021).

Cabinet Secretariat. Basic Survey on Human Connection. https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/kodoku_koritsu_taisaku/zittai_tyosa/r4_zenkoku_tyosa/index.html (2022).

Kanbay, M. et al. Social isolation and loneliness: Undervalued risk factors for disease States and mortality. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 53, e14032. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.14032 (2023).

Machida, M. et al. Individual-level social capital and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Japan: A cross-sectional study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2086773 (2022).

Aloisio, K. M., Swanson, S. A., Micali, N., Field, A. & Horton, N. J. Analysis of partially observed clustered data using generalized estimating equations and multiple imputation. Stata J. 14, 863–883 (2014).

Rubin, D. B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys Vol. 81 (Wiley, 2004).

Communications Usage Trend Survey. https://www.soumu.go.jp/johotsusintokei/tsusin_riyou/data/eng_tsusin_riyou02_2021.pdf (2021).

Kurimoto, A. et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the abbreviated Lubben social network scale. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 48, 149–157. https://doi.org/10.3143/geriatrics.48.149 (2011).

Vasan, S., Eikelis, N., Lim, M. H. & Lambert, E. Evaluating the impact of loneliness and social isolation on health literacy and health-related factors in young adults. Front. Psychol. 14, 996611. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.996611 (2023).

Stickley, A., Matsubayashi, T., Ueda, M. & Loneliness COVID-19 preventive behaviours among Japanese adults. J. Public Health 43, 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa151 (2021).

Hajek, A., Bock, J. O. & König, H. H. The role of general psychosocial factors for the use of cancer screening-findings of a population-based observational study among older adults in Germany. Cancer Med. 6, 3025–3039. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1226 (2017).

Messina, C. R. et al. Relationship of social support and social burden to repeated breast cancer screening in the women’s health initiative. Health Psychol. 23, 582–594. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.582 (2004).

Kinney, A. Y., Bloor, L. E., Martin, C. & Sandler, R. S. Social ties and colorectal cancer screening among Blacks and Whites in North Carolina. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 14, 182–189 (2005).

Okruszek, Ł., Aniszewska-Stańczuk, A., Piejka, A., Wiśniewska, M. & Żurek, K. Safe but lonely? Loneliness, anxiety, and depression symptoms and COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 11, 579181. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.579181 (2020).

Cacioppo, J. T., Norris, C. J., Decety, J., Monteleone, G. & Nusbaum, H. In the eye of the beholder: Individual differences in perceived social isolation predict regional brain activation to social stimuli. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 21, 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2009.21007 (2009).

Newall, N. E. G. & Menec, V. H. Loneliness and social isolation of older adults: Why it is important to examine these social aspects together. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 36, 925–939. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517749045 (2019).

Carstensen, L. L. The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science 312, 1913–1915. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127488 (2006).

Dykstra, P. A. & Fokkema, T. Social and emotional loneliness among divorced and married men and women: Comparing the deficit and cognitive perspectives. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 29, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973530701330843 (2007).

Perlman, D. European and Canadian studies of loneliness among seniors. Can. J. Aging 23, 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1353/cja.2004.0025 (2004).

Cloutier-Fisher, D., Kobayashi, K. & Smith, A. The subjective dimension of social isolation: A qualitative investigation of older adults’ experiences in small social support networks. J. Aging Stud. 25, 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.012 (2011).

Davies, R., Scott, A., Shahtahmasebi, S. & Wenger, G. C. Social isolation and loneliness in old age: Review and model refinement. Aging Soc. 16, 333–358. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X00003457 (1996).

Lee, Y. & Ko, Y. Feeling lonely when not socially isolated: Social isolation moderates the association between loneliness and daily social interaction. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 35, 1340–1355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517712902 (2018).

Rahbeni, T. A. et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Umbrella review of systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 10, e54769. https://doi.org/10.2196/54769 (2024).

Brackstone, K. et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and confidence in the Philippines and Malaysia: A cross-sectional study of sociodemographic factors and digital health literacy. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2, e0000742. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742 (2022).

Matthews, T. et al. The developmental course of loneliness in adolescence: Implications for mental health, educational attainment, and psychosocial functioning. Dev. Psychopathol. 35, 537–546. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579421001632 (2023).

Okubo, R., Yoshioka, T., Ohfuji, S., Matsuo, T. & Tabuchi, T. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its associated factors in Japan. Vaccines. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9060662 (2021).

Paul, E., Steptoe, A. & Fancourt, D. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Implications for public health communications. Lancet Reg. Health Europe 1, 100012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012 (2021).

Marzo, R. R. et al. Perception towards vaccine effectiveness in controlling COVID-19 spread in rural and urban communities: A global survey. Front. Public. Health 10, 958668. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.958668 (2022).

Jaspal, R. & Breakwell, G. M. Socio-economic inequalities in social network, loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 68, 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020976694 (2022).

Jetten, J., Haslam, C. & Alexander, S. H. The Social Cure: Identity, Health and Well-Being (Psychology Press, 2012).

Jetten, J. Together Apart: The Psychology of COVID-19 (Sage, 2020).

Strayhorn, T. L. College Students’ Sense of Belonging: A Key to Educational Success for all Students (Routledge, 2018).

Gopalan, M. & Brady, S. T. College students’ sense of belonging: A national perspective. Educ. Res. 49, 134–137. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x19897622 (2020).

Diehl, K., Jansen, C., Ishchanova, K. & Hilger-Kolb, J. Loneliness at universities: Determinants of emotional and social loneliness among students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091865 (2018).

Kocak, R. The effects of cooperative learning on psychological and social traits among undergraduate students. Social Behav. Personal. Int. J. 36, 771–782 (2008).

Lee, C. Y., Goldstein, S. E. & Loneliness Stress, and social support in young adulthood: Does the source of support matter?? J. Youth Adolesc. 45, 568–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0395-9 (2016).

Ames, M. E. et al. The moderating effects of attachment style on students’ experience of a transition to university group facilitation program. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 43, 1 (2011).

Page, R. M. & Hammermeister, J. Shyness and loneliness: Relationship to the exercise frequency of college students. Psychol. Rep. 76, 395–398. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1995.76.2.395 (1995).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the study participants for their contribution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.G. and N.N. conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, conducted the formal analysis, performed the investigation, and curated the data. Y.G. wrote the original draft of the manuscript. N.N. contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript. T.N., M.S., I.S., H.N., S.O. and K.W. contributed to the conceptualization, data collection, and review and editing of the manuscript. T.F. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data collection, and drafting of the original manuscript, as well as the supervision and management of the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Goto, Y., Nawa, N., Nakayama, T. et al. Loneliness, but not social isolation, is a risk factor for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in university students in Tokyo, Japan. Sci Rep 15, 17562 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01110-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01110-2