Abstract

We computed the plastic mass that the top three fast moving consumer good beverage companies (Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and Nestlé) produced from 2000 to 2023: 138 ± 12 million metric tons (MMT) of plastic, of which 14–21.1 (± 2.2 MMT) (10–15%) were projected to have turned into aquatic pollution. Around 55–60 (± 6.4 MMT) (39–43%) are estimated to have resulted in terrestrial plastic pollution, with only minor amounts (11–14.9 ± 1.6 MMT, equivalent to 8–11%) deemed recycled. For each dollar of revenue, the three companies have generated approximately 40 g of plastic, of which 49–58% become aquatic and terrestrial pollution costing countries $13–19 (± 2) billion USD globally per annum in externalities. Absent change, these companies could add an additional 339 ± 45 MMT plastic mass to countries globally by 2050, costing an estimated $101 ± 13 billion USD. Infrastructure investments in just two regions; Southeast Asia and Pacific and Latin America and the Caribbean, could abate 77% of marine bound plastics from these three companies. The present analysis suggests that fast moving consumer goods companies, with their global reach in over 200 countries, may be well positioned to change the current trajectory of global plastic pollution and ocean plastic littering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The health and wellbeing of humans and ecosystems are increasingly impacted by plastic polymers. Microplastics have been found in the depths of ocean trenches, in the tissues of animals, and even in human placentas1,2,3,4,5. Precursors to microplastics are mismanaged macroplastics (such as plastic beverage containers), with a documented history of leakage into the environment6. Cumulative plastic production is estimated to have reached 8,300 million metric tons (MMT) in 20157. The majority of that mass (56%) was created from the year 2000 onwards, with continuing growth projected absent of significant corporate or regulatory change8.

An estimated 40% of plastic waste generated in the past two decades was derived from packaging. Packaging waste has the shortest product lifetime ranging from 15 min to 16 months, with post-consumption environmental half-lives measured in decades, centuries or even millennia7. The proliferation of single-use plastic by fast-moving consumer goods companies (FMCG) has nearly doubled in the last decade9,10. PET and PP, account for 402 MMT and 718 MMT, respectively, or 63% of all plastics dispersed in the environment since the year 2000. Incidentally, the most prevalent ocean plastic were also PET and PP, which also dominate the plastic packaging11,12,13. A recent brand audit done in 85 countries found that the top three brands with the most litter were the Coca-Cola Company (11%), PepsiCo (5%), Nestlé (3%)6.

The distribution portfolio of packaging by the Coca-Cola company today is 44% PET (the highest), compared to 24% for aluminum and steel, and 9% for glass14. Indeed, North America and East Asia have an exceptionally high demand for bottled water, where it is perceived as the only source of clean drinking water15 (Statista, 2022). While the role of government, countries and consumers are explicitly highlighted in literature, comparably few studies discuss the role of industry in reducing macroplastics in any actionable manner6. In the past decade companies have made numerous commitments to reducing their contribution to plastic pollution globally, but without reported baseline values, adherence to those commitments cannot be measured reliably. Currently, economic growth and environmental pollution are irretrievably linked16. While the beverage industry is a key player in the demand, use, and proliferation of plastic products, estimates are lacking as to the amount of plastics this market sector utilizes and has dispersed into the global environment over the past two decades. Among the 32 leading beverage brands, we used available data for the three leading companies, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Nestlé, that have a combined market share of 85% of the beverage industry (Statista, 2021). First, we present the mass estimates of plastics used over the last two decades and project the business-as-usual scenario to the year 2050. Secondly, we trace the flows of plastic use to destination countries worldwide, classifying by region and income level (High Income = HI, Upper Middle Income = UMI, Lower Middle Income = LMI, Low Income = LI). Finally, plastic waste generated by these three companies are traced to their final end-of-life sinks in land and sea.

Results

Global plastic mass produced by three companies

Fast Moving Consumer Goods companies have the highest market value, totaling nearly 5000 billion USD (see SI 5 and 6). Estimate results indicate the lowest overall world production of plastic from three companies was in the year 2000 at 2.6 MMT and the highest in 2023 at 8.1 MMT, so far. The mass of plastic waste generated per annum by the three major beverage companies studied here is estimated to be in the range of 14 or 20 MMT by 2050 (Fig. 1) if trends of current consumption and waste management continue unabated. The cumulative future mass (from 2024 to 2050) is estimated to reach 339 ± 45.3MMT with a business-as-usual scenario.

Mass of plastic in million metric tons (MMT) produced by three major beverage companies, representing 85% of the global beverage market, from 2000 to 2050. The historic part of the estimation (2000–2023) and the future (2024–2050) is a function of revenue, plastic polymer trends and GDP. The highest estimates of plastic waste produced by these three companies. The maximum, average and lowest estimate of plastic waste production are represented in red, yellow and green as trendlines, with the standard deviation depicted in lighter shade. The cumulative sum area under the curve for the average estimated mass of plastics (gray middle line) made by three top beverage companies over the course of 23 years is 138 MMT, (signifying 100% of total plastic mass), with the total upper estimate being 151 MMT, and the total lower estimate being 127 MMT.

From 2000, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Nestlé produced an estimated 59.2 ± 4.7MMT, 45.3 ± 3.6MMT, and 33.2 ± 2.6MMT of plastic waste, respectively (Fig. 2). The majority of plastics are sold to high, upper-middle and lower-middle income countries. However, Coca-Cola sells the most to LMI countries (20.2 ± 2MMT), while PepsiCo sells the most to HI countries (32.8 ± 4MMT). For all companies combined, 33–37 ± 3 MMT, or 24–26% of the plastic was disposed of in sanitary landfills. Around 36–38 ± 4.1MMT is considered to have ended up in non-sanitary landfills around the world. More plastic made by these three companies is estimated to have ended up in ocean sinks (14–21.1 ± 2.1 MMT) than was recycled (11.9–14 ± 1.3 MMT).

Sankey diagram of global flows of total cumulative estimated mass of plastics (in MMT) from the top three global beverage companies from 2000 to 2023 flowing to countries and then to end-of-life sinks. (A–C), Mass flows from companies (organized by decreasing plastic waste mass), to countries (categorized by income classification and organized by decreasing population and) to waste end-of-life sinks. Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Nestlé produced an estimated 59 MMT, 45 MMT and 33 MMT of plastic waste respectively, over 2000–2023. (B) Plastic packaging sold to countries. Economies of countries (n = 217) were classified to four income levels as defined by the World Bank. (C) The flow of plastic into six designated end-of-life sinks as classified by the World Bank on waste sinks by country (n = 217 countries).

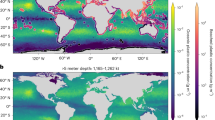

For each dollar of revenue, the three companies have generated approximately 40 g of plastic, of which 49–58% become aquatic and terrestrial pollution costing countries $13–19 (± 2) billion USD globally per annum in externalities (SI,6b,c,h). Absent change, these companies could add an additional 339 ± 45 MMT plastic mass to countries around the world by 2050, costing an estimated $101 ± 13 billion USD to collect and handle (SI, 6g). Consumption of goods from Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Nestlé increase by income classification, suggesting that the wealthier the country the more plastic is consumed. Currently, HI, and UMI income countries account for 75% of all plastic sales (Fig. 2). Although low- and middle-income countries only buy 25% of the products that come in plastic from Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Nestlé, these countries do not have adequate management infrastructure in place to manage the plastic waste post end-of-life. Assessing the results by region (Fig. 3) indicates that 82% % of Coca-Cola’s marine litter stems from their sales in Southeast East Asia & Pacific, closely followed by their sales in Latin America & the Caribbean. An estimated 71% and 74% of PepsiCo and Nestlé’s emissions to marine systems stem from their sales in Latin America & Caribbean and Southeast Asia & Pacific. This analysis suggests that around ~ 77% of their plastic pollution to oceans could be reduced via infrastructure investments in South East Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean (Fig. 3).

The percentage of plastic going into each end-of-life sink from each company organized by geographic region. Percentage of companies waste to country end-of-life sinks (organized by decreasing environmentally sound value). Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Nestlé produced an estimated 59 MMT, 45 MMT and 33 MMT of plastic waste respectively from 2000 to 2023. That mass went into six end-of-life sinks; Recycling, Incineration, Sanitary Landfill, Dumped Non-Sanitary Landfill, Mismanaged, and Marine Pollution. Each end-of-life sink was further stratified into by one of seven geographic regions.

Discussion

The average cost of collection and sorting of plastics globally is $298.75 USD/metric ton17, not including landfill and disposal fees. Thus, plastic waste from the three companies combined was estimated to have cost taxpayers $740 ± 0.8 M USD annually so far (SI, 6f). This annual cost is projected to increase to $3.8 ± 0.5 B USD per annum by the year 2050 with an additional 339 ± 45MMT of plastic waste being added (SI 4a,f,g) (Fig. 1), if practices do not change. Africa and Asia are anticipated to encompass 97% of the world’s population growth, which is expected to take place over the next three decades, as predicted by the United Nations (2001). Accordingly, Lebreton et al.18 argue that a disproportionate burden of plastic waste will occur in coastal communities in those regions. Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia are future markets for these brands, and our estimates suggest that waste management infrastructure will be unable to keep pace with the strong economic growth, leading to marine pollution, dumping in non-sanitary landfills and mismanagement of waste. Accordingly, we question the notion that countries and consumers are the most powerful actors to stop or even to take responsibility for decreasing or improving the waste management of single use plastics and plastic packaging and suggest that more fastidious actions may be taken by industry actors. Research indicates that 56 companies are responsible for half of the identifiable branded plastic pollution in land and sea6. The beverage industry in particular has an extremely fast turnover time, and thus the single-use plastics attributed to this industry are more likely to proliferate with growing markets and economies. To cap plastics into the world’s oceans could be met more easily by the FMCG industry as demonstrated by the data presented here, than by individual countries and individual consumers, as an estimated 0.6–0.9 MMT/year (cumulatively so far 2000–2023) of plastic waste ends up in oceans from just three companies.

Latin America and the Caribbean’s leaking into marine could stem from tourism, whereas Southeast Asia’s marine plastic flows could be from their consumption of bottled water. The waste that is mismanaged or recycled in the EU and USA could potentially end up in other countries after collection in western recycling centers and subsequent shipment to countries lacking both recycling and solid waste management infrastructure19.

Companies spend between 1 and 4% of their revenue on packaging. That represents $1.9B to $7.8B USD in 2019 for Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Nestlé. We note that “recyclable” does not necessarily equal actually recycled. Globally an estimated 9% of plastic is recycled7. Even though Coke, Pepsi, and Nestlé claim to use materials that are recyclable—they do not get recycled for various reasons20. Other major brands have similar commitments, ensuring a high demand for pure recycled materials, especially PET. To deliver on these commitments at scale, companies should consider investing in contamination and traceability technology to enable re-entry of plastics back into their supply chains. Lastly, clear data is a key, especially in light of the global UN plastic treaty. A reduction cannot be measured if the base value is unknown, emphasizing a need for public disclosure of plastic consumption by all FMCG companies. If the FMCG companies want to keep their recycling commitments and retrieve their packaging costs, they will have to aid the waste management industry to trace their products post end-of-life, as sentiment echoed by other scientists6,9

Conclusion

Plastics offer considerable benefits to society but their current unrestricted and unlimited use in the FMCG sector may not be sustainable. Global plastic pollution is often portrayed as a wicked problem for which solutions remain elusive. However, the present study and others6,8,21 suggest that a disproportionate amount of plastic pollution could be avoided if industry took responsibility at end-of-life. Our policy recommendation is a call for researchers and industry to develop and refine methodologies specifically focused on evaluating data collection at end-of-life and for consumer goods companies to publicly disclose, reduce, report and retrieve the packaging they sell in the various global regions that are vulnerable to plastic pollution leakage. We estimate that some 39–43% of the plastics used by the three major global beverage corporations over the last 23 years have been either openly dumped, mismanaged and some 14–21.3 ± 2.2 MMT of plastics are estimated to have found their way into ocean sinks. Upper-middle, lower-middle, and low-income countries account for about 60% of the sales market for FMCG, but it is precisely these countries that do not have adequate waste management infrastructure to manage the plastic at end-of-life. In the past two decades, three companies dispersed 81.9 ± 8.5 MMT of plastic in low, middle and upper middle-income countries respectively. Previous researchers have focused on countries and people as the responsible drivers and empowered entities to reduce global plastic waste and pollution22. Results of the present analysis suggest that a course change by a few important players could help to make real progress toward the protection of global human populations, wildlife, and threatened natural resources. With Coke, Pepsi, and Nestlé’s global reach and sales to more than 217 countries, these and other consumer goods companies can unanimously ensure a swift and comprehensive decrease in plastic pollution or a lack thereof.

Limitations

There are important limitations that must be considered. First, this study assumes that the waste produced by these three companies is indeed single-use PET and PP and not any other type of plastics. We lacked detailed data on the plastic type and understand that future waste treatment may change. This estimate also does not account for the global waste trade and assumes that waste management data collected in 2018 by the worldbank is static across the past 20 years. Furthermore, we cannot account for the price variation in polymer packaging and thus assume a direct 1:1 relationship between predictor variables such as company revenue and plastic mass, this assumption should be examined and tested in future research. These findings represent preliminary estimates, and we encourage future researchers to refine and extend this work by employing alternative methodologies and additional data sources for replication. While our estimates are limited by data availability, others are welcome to correct our estimates with proprietary data. Finally, this research does not include Coke, Pepsi, and Nestlé’s philanthropic activities in recycling infrastructure. Future work could investigate how waste trade factors into this study and map the company specific planetary boundaries for this data, while replicating this study for other companies whilst including economic considerations.

Methods

Data sources

Self-reported data on annual consumption of plastics by each individual company (Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and Nestlé) were taken from the public domain (SI, 1a) for the years 2018 and 201923. Five independent variables (1) Gross domestic product (GDP) (present-day $USD), (2) GNI/ capita (current $US), (3) total plastic polymer trends (MMT/year), (4) historic company revenue (current $USD), and (5) waste generation rate (MMT/year) were tested, to predict the dependent variable of interest: annual revenue Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Nestlé for the same years. After removing colinear variables (SI, 1e) and we used a time series forecasting model called ARIMA with the GDP as a regressor to predict company specific revenue for future years. Then, by assuming a 1:1 ratio between total polymer, GDP and historic company specific revenue as predictor variables, we obtained an estimate range of year-by-year plastic use for each company for years for missing data over two decades (2000 to 2023) and we computed anticipated values of plastic waste production for future years through 2050.

Localization of plastic waste generation by product manufacturer

Global soft drink sales, in millions of liters, by geographical region for the years 2012 and 2017 were collected (SI, 1c & 2). These data were converted to an average sales percentage for each of the seven regions of the world. Since Coca-Cola and PepsiCo are largely soft drink-based companies, this data was used as a proxy for their sales in those geographical regions. For Nestlé, sales distribution data by region was retrieved from the company website as a percentage of sales revenue for the year 2020 (SI, 1c and 2). Gathered sales percentages were multiplied with the mass in MMT for each company’s plastic waste data to arrive at the mass of plastics in MMT, deposited in each of the seven regions of the world (See SI, 1d and 2). To obtain the percentage of sales by income classification, sales data by region were weighted by the population for each of the four income classifications SI, 3).

Analysis of end-of-life fate of plastics embedded in company products

To estimate the final destination of post-consumer plastics from beverage company products, the percentage of plastic waste distributed to different final sinks for each country was applied to the estimated plastic mass by company per country using Kaza et al.24. End-of-life sinks were classified into six end of life classifications, recycling, incineration, sanitary landfill, dumping in non-sanitary landfills (denoted by Dumped NSLF*), mismanaged (as defined by the World Bank) and marine pollution (denoted by Marine P*). The end-of-life waste management data were averaged by income classification and then weighted by the population to arrive at the percentage for end-of-life sink for each of the seven world regions (SI, 2). Field studies were used to verify EOL data.

Number of fast-moving consumer goods

The top 100 wealthiest companies, as defined by their market value, was downloaded from the Forbes website25. Each company was categorized as one of the seven categories (FMCG, Tech, Tech Goods, Oil and Gas, Biotech, Financial, Media and Other, see SI, 5).

Economic burden, marine clean-up cost and externalities

Taxpayer costs were calculated using external information from Lau et al., (2021) and Borrelle et al.17, where they state that the average global cost of collection of plastic is 156.5 USD/t on plastic waste. The average cost of sorting plastic was 142.25 USD/t of plastic waste. This cost was averaged and multiplied by the total mass calculated by the above data set (SI, 6c-i). The cost of cleaning up just the plastic into Marine Environments by Nestle, PepsiCo and Coca-Cola was estimated using Beaumont et al.26 analysis on cost of marine clean-up of plastics (between 3300 and 33,000 USD/t of marine plastic) and multiplying that by the calculated mass in this study (SI, 6g,h,i).

Data visualization

All data visualizations were performed in the R software v.4.1.1.

Ethical approval

This research did not include human or animal experiments.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files and will be made public in a repository.

Abbreviations

- FMCGs:

-

Fast moving consumer goods companies

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- C:

-

The Coca-Cola Company

- P:

-

PepsiCo

- N:

-

Nestlé

- HI:

-

High-income

- UMI:

-

Upper middle-income

- LMI:

-

Lower middle-income

- LI:

-

Low income countries

- BAU:

-

Business-as-usual

- EU:

-

European union

- PE:

-

Polypropylene

- PET:

-

Polyethylene terephthalate

- B:

-

Billion

- MMT:

-

Million metric tons

References

Adhikari, S., Kelkar, V., Kumar, R. & Halden, R. U. Methods and challenges in the detection of microplastics and nanoplastics: A mini-review. Polym. Int. 71(5), 543–551. https://doi.org/10.1002/pi.6348 (2022).

Cook, C., & Halden, R. Ecological and health issues of plastic waste. Plastic Waste Recycl. 513–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-817880-5.00020-7 (2020).

Halden, R. U. Plastics and health risks. Annu. Rev. Public Health 31, 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103714 (2010).

Law, K. L. et al. Plastic accumulation in the North Atlantic subtropical gyre. Science 329(5996), 1185–1188. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1192321 (2010).

Pabortsava, K., & Lampitt, R. High concentrations of plastic hidden beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean. Nat. Commun. 11 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17932-9 (2020).

Cowger, W. et al. Global producer responsibility for plastic pollution. Sci. Adv. 10(17), eadj8275. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adj8275 (2024).

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R. & Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 3(7), e1700782. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1700782 (2017).

Pottinger, A. S. et al. Pathways to reduce global plastic waste mismanagement and greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Science 386(6726), 1168–1173. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adr3837 (2024).

Phelan, A. et al. Plastic pollution and packaging: Corporate commitments and actions from the food and beverage sector. J. Clean. Prod. 331(129827), 129827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129827 (2022).

Tan, J., Tiwari, S. K. & Ramakrishna, S. Single-use plastics in the food services industry: Can it be sustainable?. Mater. Circ. Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42824-021-00019-1 (2021).

Gewert, B., Plassmann, M. M. & MacLeod, M. Pathways for degradation of plastic polymers floating in the marine environment. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 17(9), 1513–1521. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5em00207a (2015).

Ioakeimidis, C. et al. The degradation potential of PET bottles in the marine environment: An ATR-FTIR based approach. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23501 (2016).

Van Sebille, E. et al. A global inventory of small floating plastic debris. Environ. Res. Lett. 10(12), 124006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/12/124006 (2015).

Coca-Cola. Refresh the World. Make a Difference. Business & Environmental, Social and Governance Report, 35–72. https://www.coca-colacompany.com/ (2022).

Hu, Z., Morton, L. W. & Mahler, R. L. Bottled water: United States consumers and their perceptions of water quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 8(2), 565–578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8020565 (2011).

Rao, C. & Yan, B. Study on the interactive influence between economic growth and environmental pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 27(31), 39442–39465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10017-6 (2020).

Borrelle, S. B. et al. Predicted growth in plastic waste exceeds efforts to mitigate plastic pollution. Science 369(6510), 1515–1518. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba3656 (2020).

Lebreton, L. et al. River plastic emissions to the world’s oceans. Nat. Commun. 8(1), 1–10 (2017).

Brooks, A. L., Wang, S. & Jambeck, J. R. The Chinese import ban and its impact on global plastic waste trade. Sci. Adv. 4(6), eaat0131. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aat0131 (2018).

Shen, L., & Worrell, E. Plastic recycling. In Handbook of Recycling (eds. Meskers, C. et al.) 497–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-323-85514-3.00014-2 (Elsevier, 2024).

Bachmann, M. et al. Towards circular plastics within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 6(5), 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-01054-9 (2023).

Jambeck, J. R. & Johnsen, K. Citizen-based litter and marine debris data collection and mapping. Comput. Sci. Eng. 17(4), 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1109/mcse.2015.67 (2015).

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. The Global Commitment 2019. 76. https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/resources/apply/global-commitment-progress-report (2019).

Kaza, S., Yao, L., Bhada-Tata, P., & Van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050 (World Bank Publications, 2018).

Forbes, The Global 2000 List of Companies. https://www.forbes.com/lists/global2000/?sh=2c23e5cd5ac0 (accessed Aug 2022).

Beaumont, N. J. et al. Global ecological, social and economic impacts of marine plastic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 142, 189–195 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Braden Allenby and A. Samuel Pottinger for their support, inspiration and mentorship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. N.B.: Conceptualization, methodology, data visualization, writing—original draft preparation, review and editing. Dr. S.A.: Data visualization, validation, data curation, review and editing. Dr. E.D.: Lab resources, validation, data curation, review and editing. Dr. C.S.: Methodology, review and editing. Dr. R.U.H.: Conceptualization, methodology, funding, supervision, project administration and writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Biyani, N., Adhikari, S., Driver, E.M. et al. Mass and fate estimates of plastic waste dispersed globally to marine and terrestrial environments by three major corporations. Sci Rep 15, 22074 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01679-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01679-8