Abstract

Understanding socioeconomic inequalities in health helps identify vulnerable groups and guide targeted interventions. Mental health disorders significantly affect well-being and productivity. This study assessed the prevalence and socioeconomic inequalities in depression, anxiety, and stress among employees of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences. This cross-sectional study analyzed data from the Tehran University of Medical Sciences Employees’ Cohort (TEC) baseline phase, comprising 4,442 individuals. The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-42 (DASS-42) was utilized to measure mental health disorders. Education level and wealth index were considered as socioeconomic indicators. The Slope Index of Inequality (SII) and the Relative Index of Inequality (RII) were employed to estimate socioeconomic inequality. The age-adjusted prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress was 8.7%, 8.6%, and 11.5%, respectively. The relative wealth-related inequality analysis revealed that, after adjusting for age, sex, marital status, and education level, the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress in the lowest wealth index was 2.54, 2.89, and 1.65 times higher than in the highest wealth index, respectively. Additionally, the relative education-related inequality analysis indicated that, adjusted for age, sex, marital status, and wealth index, individuals with primary education or no formal education had 2.58, 2.99, and 2.14 times higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress compared to those with a doctoral degree, respectively. Significant disparities in the prevalence of mental health disorders were found across educational and wealth index levels. Targeted interventions and policies should aim to achieve and sustain long-term benefits for vulnerable and disadvantaged groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2019, an estimated 970 million people globally were living with a mental disorder, with anxiety and depression being the most common1. Mental disorders account for 1 in 6 years lived with disability worldwide1. In Iran, a developing country, the prevalence of mental disorders has increased in recent decades, with depressive and anxiety disorders among the top 10 causes of death and disability in 20192. Evidence has shown that mental health is related to sleep quality, quality of life, and overall mortality3,4,5. Additionally, mental disorders can reduce functional ability and lead to disabilities and suicide6,7.

Mental health disorders—particularly anxiety and depression—are highly prevalent in the working population8,9. These conditions are closely associated with reduced productivity, increased absenteeism, and work-related disability10,11. Global estimates indicate that depression and anxiety contribute to the loss of approximately 12 billion working days each year, resulting in an economic burden of around $1 trillion due to diminished productivity12. So, addressing mental health within the workforce and identifying disparities in mental disorders is of critical importance. On the other hand, socioeconomic status (SES) is a key determinant of such disparities13. Individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds often experience more life stressors and have limited access to quality healthcare services14. Similarly, employees from lower SES backgrounds may also experience elevated levels of work-related stress and reduced access to mental health resources compared to their more advantaged peers15.

While various studies globally and within Iran have examined the association between social determinants of health and health-related outcomes, to our knowledge, no cohort study has comprehensively assessed these associations or the trends in socioeconomic inequalities in health over time in Iran. Furthermore, given the worsening economic conditions, recent sanctions16, rising inflation17, and social crises in Iran, the necessity of conducting a cohort study focusing on social determinants of health has become even more pronounced. Mental health remains one of the most critical health outcomes, with evidence indicating an increasing prevalence of mental disorders and their severe consequences, such as suicide. Therefore, it is essential to design context-based studies to enhance current knowledge and provide appropriate evidence for evaluating the impact of interventions. In response to this gap, several cohort studies have recently been launched in Iran to provide context-based evidence18. Among these, the cohort study of employees at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences stands out for its specific focus on the social determinants of health. Given the diversity of its workforce and socioeconomic backgrounds, this setting provides an ideal opportunity to assess socioeconomic inequalities in mental health and their trends using various SES indicators19. The present study evaluated educational and wealth-related socioeconomic inequalities in mental health disorders among employees of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, using data from the Tehran University of Medical Sciences Employees’ Cohort (TEC) baseline phase.

Methods

Study population

This cross-sectional study was conducted on individuals participating in the baseline phase of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences Employees’ Cohort (TEC). Data collection began in 2018, and all data were collected by 15 trained staff through face-to-face interviews. The inclusion criteria for the TEC study were any employment status within TUMS and its affiliated centers. The study population comprised administrative, clinical, and academic staff from the university and its affiliated centers. No exclusion criteria were applied for the current analysis; all participants in the TEC study were included, resulting in a total sample of 4,442 individuals. More details regarding the study design can be found in previous publications19.

Data collection

Details of the data collection procedures for the TEC study have been described in full elsewhere20. In brief, multiple methods were employed, including clinical sampling, interview-based questionnaires, and physical examinations. Interviews were conducted by trained personnel holding at least a bachelor’s degree. The present study utilized data on age, sex, marital status (single, married, divorced, or widowed), socioeconomic status, and mental health.

Mental health

Mental health was assessed using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-42 (DASS-42)21. The Persian version of DASS-42 has been previously found valid and reliable in the Iranian population. The DASS-42 is a 42-item questionnaire that assesses mental health in three subscales: depression, anxiety, and stress. Each subscale is evaluated with 14 questions, with scores ranging from 0 to 42. Participants were classified into two groups based on their subscale DASS-42 scores. A score ≥ 21 for depression, ≥ 15 for anxiety, and ≥ 26 for stress was considered indicative of a mental disorder for each subscale22. These cutoffs correspond to severe to extremely severe levels of symptoms, as defined by the Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS).

Socioeconomic status

The education level and household wealth index were assessed to measure socioeconomic status. Participants were classified into seven groups based on their education level: no formal education/primary, intermediate, diploma, associate degree, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, and doctoral degree. Additionally, the household wealth index was created based on ownership of specific assets, including a dishwasher, microwave, personal computer (PC or laptop), washing machine, color television (LCD or LED), video players (VHS or VCD or DVD), access to the internet at home, possession of a personal vehicle (not for work or income), and housing ownership status (owner or tenant), alongside metrics such as the number of rooms per capita and living area per capita.

Statistical analysis

The Categorical Principal Components Analysis (CATPCA) approach was applied to construct a household wealth index based on household assets23. The age-adjusted prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress was estimated across different education levels and wealth quintiles. We employed two widely used indices to quantify socioeconomic inequalities: the Slope Index of Inequality (SII) and the Relative Index of Inequality (RII). Both indices adopt a regression-based approach to measure absolute and relative socioeconomic inequalities in mental health, respectively24. Both the SII and the RII provide interpretable measures of the magnitude and direction of socioeconomic inequalities.

The SII and RII values with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated employing Poisson regression models. To estimate RII, individuals were ranked according to their socioeconomic status (from the highest wealth index or highest level of education (0) to the lowest (1). The RII denotes the ratio of the prevalence of mental disorders between individuals at the highest socioeconomic rank to those ranked at the lowest socioeconomic status. In the case of SII, the absolute difference in the prevalence of mental health disorders between those in the highest and lowest ranks was estimated. An RII greater than 1 indicates a higher prevalence of the risk factors among individuals with lower socioeconomic status. In comparison, an SII greater than 0 suggests a higher prevalence among individuals of lower socioeconomic status than those of higher status. An RII of 1 and an SII of 0 indicate the absence of socioeconomic inequality in the prevalence of the studied outcomes. Our analysis first estimated age-adjusted RII and SII in the initial model. Subsequently, in the second model, we further adjusted these estimates for age, sex, marital status, and either wealth index or education level. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 14 software.

Ethical consideration

This study was conducted following the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences approved this project under code IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1398.246. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Results

In total, 4442 participants were included in this study. The mean and standard deviation (SD) of age were 42.3 ± 8.8 years. The age-adjusted prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress was 8.7, 8.6, and 11.5, respectively. The age-adjusted prevalence of depression in the poorest wealth quintile was 13.6%. In the richest wealth quintile, it was 4.6%. Similarly, the age-adjusted prevalence of anxiety in participants with no formal/primary education was 13.3%, and it was 2.9% in participants with doctoral degrees (Table 1).

Subgroup analysis by sex showed that a common mental disorder in both sexes was anxiety (13.8% in females and 8% in males). In both sexes, the age-adjusted prevalence of mental disorders was different in socioeconomic strata. For instance, the age-adjusted prevalence of anxiety in females who had no formal/primary education was 22.0%, while it was 5.1% in females with doctoral degrees. More details are presented in Table 1.

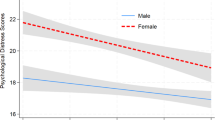

Table 2 presents the absolute and relative measures of wealth-related inequality in the prevalence of mental health disorders. A visual representation of these findings is provided in Fig. 1, which illustrates the SII and RII estimates across wealth quintiles. According to SII, the difference in the prevalence of anxiety between the lowest and highest wealth quintiles was 11.07% (SII = 11.07; 95% CI: 8.27–13.88, p < 0.001). After adjusting for age, sex, marital status, and education, the difference in the prevalence of anxiety between the lowest and highest wealth index quintiles was 6.94% (SII = 6.94; 95% CI: 3.62–10.27, p < 0.001). Additionally, according to the RII, after adjusting for age, the prevalence of depression in the lowest wealth quintile was 3.26 times higher than that in the highest wealth quintile (RII = 3.26; 95% CI: 2.26–4.71, p < 001). In model 2, adjusted for age, sex, marital status, and education, the prevalence of depression in the lowest wealth quintile was 2.54 times higher than that in the highest wealth quintile (RII = 2.54; 95% CI: 1.64–3.93, p < 0.001) (Table 2; Fig. 1).

In females, based on SII, after adjusting for age, the difference in the prevalence of depression between the lowest and highest wealth quintiles was 15.66% (SII = 15.66; 95% CI: 11.50–19.82, p < 0.001). In model 2, the difference in the prevalence of depression between the lowest and highest wealth quintiles was 11.47% (SII = 11.47; 95% CI: 6.81–16.12, p < 0.001). Regarding RII, in model 1, the prevalence of depression in the lowest wealth quintile was 5.03 times higher than that in the highest wealth quintile (RII = 5.03; 95% CI: 3.26–7.76, p < 0.001). In model 2, the prevalence of depression in the lowest wealth quintile was 3.30 times higher than in the highest wealth quintile (RII = 3.30; 95% CI: 1.99–5.48, p < 0.001).

In males, after adjusting for age, the difference in the prevalence of anxiety between the lowest and highest wealth quintiles was 6.08% (SII = 6.08; 95% CI: 2.10–10.07, p < 0.001). Based on RII, after adjusting for age, the prevalence of anxiety in the lowest wealth quintile was 2.58 times higher than that in the highest wealth quintile (RII = 2.58; 95% CI: 1.26–5.32, p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of depression and stress between the lowest and highest wealth quintiles in male participants, as observed in models 1 and 2 based on SII and RII.

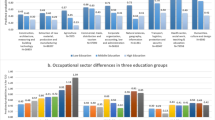

Table 3 summarizes the absolute and relative education-related inequalities in the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress. These results are further illustrated in Fig. 2, which provides a forest plot of the SII and RII values across educational levels, enhancing the interpretability of the observed disparities. In model 1, adjusted for age, the prevalence of anxiety was 10.69% higher in people with no formal/primary education than in people with a doctoral degree (SII = 10.69; 95% CI: (7.85–13.52, p < 0.001). In model 2, the prevalence of anxiety in participants with primary education or no formal education was 7.01% higher than in participants with a doctoral degree (SII = 7.01; 95% CI: 3.76–10.26, p < 0.001). In model 1 for RII, the prevalence of anxiety among participants with primary education or no formal education was 4.01 times higher than among those with a doctoral degree (RII = 4.01; 95% CI: 2.77–5.94, P < 0.001). Moreover, after further adjustment for age, sex, marital status, and wealth index (Model 2), this association remained significant, with participants in the lowest educational category exhibiting a 2.99 times higher prevalence of anxiety compared–those with doctoral degrees (RII = 2.99; 95% CI: 1.90–4.70, p < 0.001) (Table 3; Fig. 2).

Discussion

The present study aimed to estimate the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress, as well as to examine socioeconomic inequalities in the prevalence of these mental health disorders in Tehran University of Medical Sciences employees. Results indicated that stress was the most commonly reported mental health disorder among participants. We also observed significant inequalities in the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress across different levels of education and wealth in the overall population. Subgroup analysis by sex revealed that wealth-related inequalities were significant among females but not among males. However, education-related inequalities in mental health were evident in both men and women.

This study found that the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress was 8.7%, 8.6%, and 11.5%, respectively. In a population-based cross-sectional study conducted in Ilam, Iran, utilizing the DASS-21 questionnaire, the prevalence of severe depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms was found to be 19.90%, 25.95%, and 15.75%, respectively25. Based on a systematic review and meta-analysis, the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress, as measured by the DASS-21 questionnaire, among nurses working in Iranian hospitals was 30%, 28%, and 38%, respectively26. In another study conducted by Niemeyer et al., which focused on the German adult population and utilized the DASS-21 questionnaire, 9.4% of the participants reported severe and very severe depression symptoms27. A study conducted on Jordanian nurses using DASS-42 revealed that about 64% of participants had symptoms of depression, 58.8% had symptoms of anxiety, and 46.6% had symptoms of stress28. The results of a study using data from the Tehran Cohort Study showed that the prevalence of depression was 43% and anxiety was 40%, according to the General Health Questionnaire version 28 (GHQ-28)29. Similarly, a population-based study of 24,584 participants over the age of 15 in Iran reported a 29.7% prevalence of mental health disorders based on the GHQ-2830. The prevalence in our study population was similar to that observed in studies conducted on community-dwelling individuals. Variations in measurement tools and population demographics may contribute to differences in the prevalence of mental disorders across different geographic regions.

The observed sex differences in the prevalence of mental disorders are consistent with findings from numerous previous studies31,32,33, which have reported higher rates of depression, anxiety, and stress among females compared to males. Several biological and psychosocial factors may help explain these disparities34,35. Clinical data shows that females experience higher rates of depression and anxiety during times of notable hormonal changes, such as the premenstrual, postpartum, and perimenopausal phases36,37. Additionally, women are more likely to encounter psychosocial stressors and are often quicker to recognize and report symptoms of mental health conditions. They may also respond differently to stress due to socially constructed gender roles and expectations38. Workplace-related factors may further contribute to these disparities. For instance, women are less likely than equally qualified men to attain high-reward positions or leadership roles and often face wage disparities, even when controlling for education and full-time employment status39,40. Together, these factors may compound the risk of mental health issues among female employees.

As expected, the prevalence of mental disorders was higher among individuals in the lowest wealth quintile compared to those in the highest, consistent with findings from previous studies25,41. The results of a survey conducted among individuals over the age of 15 in Tehran indicated a significant socioeconomic inequality in mental health. In this study, the concentration index was used to quantify socioeconomic inequality42. Subgroup analysis by sex indicated considerable inequality in the prevalence of mental health disorders among females, but this inequality was not observed in males. One possible explanation is the complex interplay of other contributing factors, such as biological, psychosocial, and environmental factors, that may impact mental health outcomes independently of socioeconomic status37,43. Studies indicate that an increase in income has a slightly more substantial impact on the mental well-being of females than males43,44. Prior research suggests that women may be more susceptible to the adverse mental health effects of social isolation caused by income inequality45,46,47. Females tend to report mental health symptoms at earlier stages than males, and there are notable gender differences in how individuals respond to stressors38.

Results were compatible with previous studies that considered depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms to be higher in people with low education levels27,33,48. Prior research has identified two main mechanisms linking educational attainment to mental health: social causation and social selection. These mechanisms are often discussed in terms of causality, positing that higher levels of education lead to increased economic resources, reduced chronic stressors, healthier behaviours, enhanced social support, and improved mental health outcomes49,50. An alternative explanation suggests that unmeasured factors such as early-onset mental health issues, familial characteristics, genetic predispositions, and biological health conditions may confound the relationship between education and mental health (based on this hypothesis, educational attainment was a proxy)49. However, educational attainment is an important and established factor in mental health and should be considered. In addition to statistical significance, the effect sizes reported in this study, specifically the RII and the SII, offer valuable insights into the magnitude of socioeconomic inequalities in mental health. For example, the adjusted RII values demonstrated that individuals in the lowest wealth quintile were 2.54 times more likely to experience depression and 2.89 times more likely to experience anxiety compared to those in the highest wealth quintile. These differences are not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful, indicating substantial inequalities in mental health outcomes. The magnitude of these disparities highlights the need for targeted public health interventions and emphasizes the critical role of socioeconomic status in identifying vulnerable groups at greater risk of mental health disorders. The clinical and public health relevance of these findings lies in their potential to guide resource allocation and support the development of interventions aimed at improving access to mental health services among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.

Limitations and considerations

The study benefits from a robust strength in its large sample size, providing statistical power to detect meaningful patterns. Additionally, using trained interviewers enhances the reliability and validity of the data collection process, ensuring accurate and consistent responses from participants. However, the current study had certain limitations, particularly concerning the self-reported assessment of socioeconomic status, which may be threatened by response bias. Moreover, the data were derived from a cross-sectional study; therefore, causal interpretations of the associations between socioeconomic factors and health should be approached with caution. It is important to note that there is not much difference in government employees’ income (as a variable affecting wealth) due to the government’s standardized pay policies. However, there can be variations in the level of education among the employees.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated significant socioeconomic inequalities in the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among employees at a major medical university. Stress was the most commonly reported mental health condition, and both lower educational attainment and lower wealth status were strongly associated with a higher prevalence of mental disorders. These findings emphasize the importance of addressing mental health through the lens of social determinants and support the implementation of targeted, equity-focused interventions. Improving access to affordable mental health services, raising awareness, and addressing the root causes of socioeconomic disadvantage are essential steps toward reducing mental health disparities in institutional workforces. Future longitudinal research is needed to explore the causal pathways linking socioeconomic status and mental health, and to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of interventions aimed at promoting equity in mental well-being.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TEC:

-

Tehran University of Medical Sciences employees’ cohort

- DASS-42:

-

The depression, anxiety, and stress scale-42

- SII:

-

Slope index of inequality

- RII:

-

Relative index of inequality

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- CATPCA:

-

Categorical principal components analysis

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

References

Global and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 9, 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(21)00395-3 (2022).

Global burden of 369. diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1204–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30925-9 (2020).

Delbari, A. et al. Evaluation of sleep quality and related factors in community-dwelling adults: Ardakan cohort study on aging (ACSA). J. Res. Health Sci. 23, e00591. https://doi.org/10.34172/jrhs.2023.126 (2023).

Maddalena, N. C. P., Lucchetti, A. L. G., Moutinho, I. L. D., Ezequiel, O. & Lucchetti, G. d. S. Mental health and quality of life across 6 years of medical training: A year-by-year analysis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 70, 298–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640231206061 (2024).

Vogt, T., Pope, C., Mullooly, J. & Hollis, J. Mental health status as a predictor of morbidity and mortality: A 15-year follow-up of members of a health maintenance organization. Am. J. Public Health 84, 227–231. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.84.2.227 (1994).

Brådvik, L. Suicide risk and mental disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15092028 (2018).

Ross, R. E., VanDerwerker, C. J., Saladin, M. E. & Gregory, C. M. The role of exercise in the treatment of depression: Biological underpinnings and clinical outcomes. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 298–328. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01819-w (2023).

Almutairi, A. F. et al. The prevalence and associated factors of occupational stress in healthcare providers in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Gen. Med. 809–816. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S446410 (2024).

Kakemam, E. et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress and associated reasons among Iranian primary healthcare workers: A mixed method study. BMC Prim. Care. 25, 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02268-w (2024).

Harvey, S. et al. Depression and work performance: An ecological study using web-based screening. Occup. Med. 61, 209–211. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqr020 (2011).

Martin, J. K., Blum, T. C., Beach, S. R. & Roman, P. M. Subclinical depression and performance at work. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 31, 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00789116 (1996).

Word Health Organization: Mental health at work (2022). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work.

Molarius, A. et al. Mental health symptoms in relation to socio-economic conditions and lifestyle factors—a population-based study in Sweden. BMC Public. Health 9, 302. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-302 (2009).

Yu, Y. & Williams, D. R. Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health151–166 (Springer, 1999).

Schelleman-Offermans, K. et al. Socio-economic inequities in mental health problems and wellbeing among women working in the apparel and floriculture sectors: Testing the mediating role of psychological capital, social support and tangible assets. BMC Public. Health. 24, 1157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18678-5 (2024).

Mohamadi, E. et al. Impacts of economic sanctions on population health and health system: A study at national and sub-national levels from 2000 to 2020 in Iran. Glob. Health 20, 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-024-01084-2 (2024).

Hemmati, M., Tabrizy, S. S. & Tarverdi, Y. Inflation in Iran: An empirical assessment of the key determinants. J. Econ. Stud. 50, 1710–1729. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-07-2022-0370 (2023).

Poustchi, H. et al. Prospective epidemiological research studies in Iran (the PERSIAN cohort study): Rationale, objectives, and design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 187, 647–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx314 (2017).

Nedjat, S. et al. Prospective cohort study on the social determinants of health: Tehran university of medical sciences employees` cohort (TEC) study protocol. BMC Public. Health. 20, 1703. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09798-9 (2020).

Nedjat, S. et al. Prospective cohort study on the social determinants of health: Tehran university of medical sciences employeescohort (TEC) study protocol. BMC Public. Health. 20, 1–7 (2020).

Lovibond, S. H. & Lovibond, P. F. Depression anxiety stress scales. Psychol. Assess. (1995).

Lovibond, S. H. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (Psychology Foundation of Australia, 1995).

Sartipi, M., Nedjat, S., Mansournia, M. A., Baigi, V. & Fotouhi, A. Assets as a socioeconomic status index: Categorical principal components analysis vs. latent class analysis. Arch. Iran. Med. 19, (2016).

Moreno-Betancur, M., Latouche, A., Menvielle, G., Kunst, A. E. & Rey, G. Relative index of inequality and slope index of inequality: A structured regression framework for estimation. Epidemiology 26, 518–527. https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0000000000000311 (2015).

Kakaei, H. et al. High prevalence of mental disorders: a population-based cross-sectional study in the City of Ilam, Iran. Front. Psychiatry 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1166692 (2023).

Hemmati, F. et al. The prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress in nurses working in Iranian hospitals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Review/Przegląd Epidemiologiczny 75 (2021).

Niemeyer, H., Bieda, A., Michalak, J., Schneider, S. & Margraf, J. Education and mental health: Do psychosocial resources matter? SSM Popul. Health 7, 100392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100392 (2019).

Al-al, A. The association between workplace bullying and the mental health of Jordanian nurses and its predictors: A cross-sectional correlational study. J. Workplace Behav. Health 40, 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2024.2322725 (2025).

Bahrami, M. et al. Epidemiology of mental health disorders in the citizens of Tehran: A report from Tehran cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 23, 267. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04773-1 (2023).

Noorbala, A. A. et al. Survey on mental health status in Iranian population aged 15 and above one year after the outbreak of COVID-19 disease: A population-based study. Arch. Iran. Med. 25, 201–208. https://doi.org/10.34172/aim.2022.35 (2022).

Otte, C. et al. A meta-analysis of cortisol response to challenge in human aging: Importance of gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology 30, 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.06.002 (2005).

Sheikh, M. A., Abelsen, B. & Olsen, J. A. Clarifying associations between childhood adversity, social support, behavioral factors, and mental health, health, and well-being in adulthood: A population-based study. Front. Psychol. 7, 727. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00727 (2016).

Yousefzade, S. H., Pilafkan, J., Rouhi Balasi, L., Hosseinpour, M. & Khodadady, N. Prevalence of mental disorders in the general population referring to a medical educational center in Rasht, Iran. JOHE 3, 32–36. https://doi.org/10.18869/acadpub.johe.3.1.32 (2014).

Kajantie, E. & Phillips, D. I. The effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31, 151–178 (2006).

Kudielka, B. M. & Kirschbaum, C. Sex differences in HPA axis responses to stress: a review. Biol. Psychol. 69, 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.11.009 (2005).

Douma, S. L., Husband, C., O’Donnell, M. E., Barwin, B. N. & Woodend, A. K. Estrogen-related mood disorders: Reproductive life cycle factors. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 28, 364–375. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-200510000-00008 (2005).

Solomon, M. B. & Herman, J. P. Sex differences in psychopathology: Of gonads, adrenals and mental illness. Physiol. Behav. 97, 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.02.033 (2009).

Bebbington, P. E. Sex and depression. Psychol. Med. 28, 1–8 (1998).

Galos, D. R. & Coppock, A. Gender composition predicts gender bias: A meta-reanalysis of hiring discrimination audit experiments. Sci. Adv. 9, eade7979. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ade7979 (2023).

Joshi, A., Oh, S. & DesJardine, M. A. New perspective on gender bias in the upper echelons: Why stakeholder variability matters. Acad. Manage. Rev. 49, 322–343. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2021.0131 (2023).

Azaraeen, S., Memarian, S. & Fakouri, E. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders and the related demographic factors among the patients referred to comprehensive health centers in Jiroft 2017. J. Jiroft Univ. Med. Sci. 7, 422–431 (2020).

Morasae, E. K. et al. Understanding determinants of socioeconomic inequality in mental health in Iran’s capital, Tehran: A concentration index decomposition approach. Int. J. Equity Health 11, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-11-18 (2012).

Zhang, R., Feng, D., Xia, J. & Wang, Y. The impact of household wealth gap on individual’s mental health. BMC Public Health 23, (1936). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16871-6 (2023).

Owens, C. & Hadley, C. The relationship between mental well-being and wealth varies by wealth type, place and sex/gender: Evidence from Namibia. Am. J. Hum. Biol. e24064. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.24064 (2024).

Glise, K., Ahlborg, G. & Jonsdottir, I. H. Course of mental symptoms in patients with stress-related exhaustion: Does sex or age make a difference? BMC Psychiatry 12, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-18 (2012).

Höglund, P., Hakelind, C. & Nordin, S. Severity and prevalence of various types of mental ill-health in a general adult population: Age and sex differences. BMC Psychiatry 20, 209. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02557-5 (2020).

Patel, V. et al. Income inequality and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association and a scoping review of mechanisms. World Psychiatry 17, 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20492 (2018).

Williams, D. R., Yan, Y., Jackson, J. S. & Anderson, N. B. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J. Health Psychol. 2, 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910539700200305 (1997).

Halpern-Manners, A., Schnabel, L., Hernandez, E. M., Silberg, J. L. & Eaves, L. J. The relationship between education and mental health: New evidence from a discordant twin study. Soc. Forces. 95, 107–131. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sow035 (2016).

Ritsher, J. E. B., Warner, V., Johnson, J. G. & Dohrenwend, B. P. Inter-generational longitudinal study of social class and depression: A test of social causation and social selection models. Br. J. Psychiatry 178, s84–s90. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.178.40.s84 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This study was/has been done with the cooperation/support of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) employees’ cohort (TEC) study (Grant no: 36600).

Funding

The authors did not receive any funds for the publication of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G., F.G., and V.B. made substantial contributions to the study conception, the analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. S.A., P.Z., F.Z.D., and M.S. contributed to the interpretation of data, and revised the manuscript critically. H.P. participated in the acquisition, and interpretation of data and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors agreed on the final manuscript prior to submission. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted following the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences approved this project under code IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1398.246. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghorbani, S., Ghavidel, F., Abdollahi, S. et al. Socioeconomic inequality in mental health disorders: A cross-sectional study from the Tehran University of Medical Sciences employees’ cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 17796 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02192-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02192-8