Abstract

Although numerous studies have investigated the impact of urban green spaces on health, the association between street-level greenery and domain-specific physical activity (PA) among older adults remains underexplored. This study employed Baidu Street View imagery and deep learning techniques to objectively evaluate street greenery exposure and its relationship with various types of PA among older adults in China. We conducted a cross-sectional study involving 1326 older adults (aged 60 years and above) residing in Beijing, China. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) was used to assess participants’ PA levels. Street greenery was measured within a 500 m buffer around each participant’s residence using Baidu Street View images and deep learning algorithms. Data were analyzed using ANOVA, Chi-square tests, and multilevel linear regression models. Correlation analyses revealed that street greenery within a 500 m buffer of participants’ residences was significantly and positively associated with transportation PA among older adults (p < 0.05), particularly with bicycling (p < 0.01). After adjusting for individual characteristics, annual household income, and other potential confounders, multilevel linear regression analysis indicated that street greenery remained a significant positive predictor of transportation PA (β = 0.08, p < 0.01). No significant associations were found between street greenery and either leisure PA or household PA (p > 0.05). Street greenery around residential areas is significantly associated with transportation PA among older adults in China. Urban green space planning should prioritize enhancing street greenery and creating safe, pleasant walking and cycling environments to support active aging in high-density cities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the gradual increase of the older population, population aging has become a seriously global issue. It has been reported that the global population of people aged 65 and over is expected to reach 16.7% by 20501. China currently has the largest aging population, with 18.7% of its citizens aged 60 and above as of 2020, posing significant challenges to social development2. In the face of the challenges of population ageing, there is an urgent need to construct age-friendly cities that provide supportive environments and services tailored to the needs of older adults. Well-designed urban planning and infrastructure can offer safe and accessible spaces for physical activity (PA), thereby encouraging older adults to engage in exercise3,4. In addition, community services and amenities in friendly cities provide diverse options for health promotion and PA for older adults5, who will be more willing to engage in PA, improve their physical fitness and slow down the ageing process, thereby promoting healthy ageing and harmonious social development.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines PA as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure, noting that both moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity PA can confer health benefits6. Numerous studies have demonstrated that PA plays a vital role in healthy aging by slowing physical and functional decline, highlighting the importance of incorporating PA into healthy aging policies7. Recent studies on promoting PA among older adults have demonstrated that built environments significantly influence PA levels. In particular, green space, a key component of the environment, has been associated with increased PA participation and improved health outcomes in this population8,9. Some researchers even advocate for the construction of greenways as an effective public health intervention10.

Green space is defined as space created by green plants, including green areas or parks composed of lawns, shrubs, and trees11. The health-promoting effects of green spaces emerge through active human–environment interactions. These natural environments serve as therapeutic landscapes where participatory engagement mediates health improvements, creating a dynamic interface between ecological elements and human behavior that positively influences health outcomes12. Research has shown that the association between green space and health is particularly strong among individuals of lower socioeconomic status and older adults13,14. For instance, a prospective cohort study found that the presence of green space in residential neighborhoods helped prevent age-related declines in PA15.

However, the impact of green space on PA may differ based on the type of green space and the specific form of PA involved16. Currently, green space exposure is measured using various indicators, such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), park accessibility, and green land cover. NDVI is calculated based on remotely sensed satellite imagery and is used as a measure of the abundance of plant cover. One study found a significant association between NDVI levels within a 500-m buffer around residences and healthy weight status among older adults17. Additionally, a study in the United States reported a positive correlation between the percentage of neighborhood green land cover and daily minutes of walking among older adults18. Xie et al.19 also demonstrated that park accessibility was associated with better health outcomes in this population. Conversely, some studies have found no significant association between proximity to parks, park size, and levels of PA20,21.

The association between street greenery and PA has garnered increasing attention in recent years. Street greenery is often assessed through streetscape imagery and the Green View Index (GVI) is the percentage of vegetation pixels in a streetscape photograph based on eye level, which more closely approximates the level of exposure to green space as perceived by the human eye’s perspective22. Compared with traditional green space assessment methods, street greenery better reflects the real perceived green exposure environment in the daily life of individuals. He et al. reported a positive correlation between street greenery and time spent on PA among older adults9. Similarly, a study conducted in Hong Kong found that street greenery was positively associated with walking frequency and total walking time among older adults23. However, findings on the relationship between street greenery and active travel remain mixed. While some studies have demonstrated a positive association between street greenery and active travel behavior24, others reported that higher GVI values were negatively associated with the likelihood of active travel25. These inconsistencies may be attributed to variations in study settings, population characteristics, and PA types.

A review of prior studies suggests that the method used to assess green space exposure may significantly influence its observed relationship with PA. Current evidence on the effects of green environments on older adults’ PA remains inconclusive. In the context of the increasing trend of population aging, there is a need to explore in depth the specific effects of green space environments on older adults. Focusing on the interaction between individuals and the environment, this study selects the GVI as a green space exposure indicator, extends the traditional two-dimensional measurement method to the three-dimensional level. By integrating static Baidu Street View images with deep learning techniques, this approach aims to more accurately capture the visual perception of green exposure. Prior research has established that different types of PA play a critical role in promoting the health and quality of life of older adults26,27. Street greenery may provide accessible and diverse settings for PA among this population. However, few studies have specifically examined the relationship between street greenery and different types of PA in older adults.

Therefore, this study aims to explore the association between street greenery and different types of PA among Chinese older adults using Baidu Street View images and deep learning. The findings are expected to inform urban green space planning and provide valuable insights for policymakers.

Methods

Participants

The study was conducted in October 2023 using a cross-sectional design. Data for this study were obtained from the Tsinghua University Retiree Health Survey28. Participants were recruited from an all-university party organized by Tsinghua University for retired faculty and staff, where participants were recruited to participate in a health survey. Before the study began, the researcher introduced the purpose and procedures of the study to the participants. Those who agreed to participate signed an informed consent form and completed the questionnaire. The questionnaire collected information on the demographics and socioeconomic status of the retirees, their level of education, health behaviors, health conditions, and level of PA. As soon as participants submitted the questionnaire, trained graduate students checked the submitted questionnaire for completeness. Participation in the survey is voluntary and a gift of $1 will be given upon receipt of a completed questionnaire. In China, people aged 60 years and above are referred to as the older adults, so we included only retired faculty and staff aged 60 years and above in this study. All participants were able to engage in PA independently and had lived in their residence for more than one year, and data from a total of 1326 retired older adults were included in this study. The study protocol was approved by the local research ethics committee.

Measurement of street greenery

The eye-level street greenery was derived from Baidu street view images using the PSPNet technique29. Baidu Street View Map is one of the Chinese biggest street view image providers22. The street greenery measurement process is as follows. Firstly, the coordinates corresponding to the home address information of the older people in the questionnaire were obtained. Secondly, a buffer zone with a 500 m radius is delineated, with this coordinate as the center. The 500 m buffer zone was chosen mainly because, based on the review of prior literature and the characteristics of the study population30,31,32, the 500 m buffer zone may more closely reflect the real activity environment and behavioral habits of older adults. Thirdly, sampling points are set within the buffer zone, using ArcGIS software. Specifically, sampling points were generated at 50 m intervals and covered the entire road network within the 500 m buffer zone, in order to comprehensively capture the street greenery exposure experienced by the older adults. Fourthly, the sampling points are inputted into a Python script that utilized Baidu Maps’ API interface to download four Street View images with a 90° field of view for each point. Finally, these street view images are merged to construct a panoramic visual representation of each sampling point33.

The quantity of street greenery was measured by the GVI. Previous studies have confirmed the accuracy of deep learning models in image segmentation34,35. In this study, a deep learning model named PSPNet was used to obtain the GVI from street view images. After the training, PSPNet can accurately and stably segment the greenery in the street view images and calculate the GVI. As shown in the following equation, GVI calculates the proportion of street greenery pixels in the total pixels of the photo, which is the ratio of greenery pixels to total pixels in the four images22,36. The “i” in the equation is the streetscape image corresponding to each point. The GVI ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating more street greenery.

Measurement of physical activity

In this study, the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) was mainly used to assess the PA level of older adults. The PASE is an extensively validated self-administered assessment tool for measuring PA in Chinese older adults37,38,39. This study assessed older adults’ leisure PA, transportation PA, and household PA in the past week.

Leisure PA refers to activities performed during leisure time, such as walking in the park, playing Tai Chi, and keeping fit. For Leisure PA, PASE categorizes it into three intensity levels, which are light physical activity (LPA), moderate physical activity (MPA), and vigorous physical activity (VPA). The total number of hours of LPA in the past week is based on responses to two questions in the PASE assessment tool38—"How many days in the past seven days have you engaged in the following LPA? For example, yoga, watering flowers, hiking, etc.?" and "On average, how many hours per day do you spend engaged in LPA? The same structure was used for MPA and VPA, with relevant activity examples such as table tennis for MPA, and tennis, or soccer for VPA. The total duration of each activity type was computed by multiplying the number of days by the average daily duration.

Household PA refers to activities performed to accomplish daily household chores, such as cooking, sweeping, and laundry. The total number of hours of household PA in the past week is based on responses to two questions in the PASE assessment tool38—"How many days in the past 7 days have you engaged in the following household physical activities? For example, cooking, dishes, laundry, cleaning, etc.?" and "On average, how many hours per day do you spend engaged in household PA? Multiply the average number of hours of household PA per day by the corresponding number of days to calculate the total number of hours of household PA for the last week.

Transportation PA refers primarily to activities undertaken to reach a destination, such as walking or cycling to shop, work, school, etc., and encompasses walking activities and cycling activities for transportation purposes. Total hours of walking in the last week were constructed based on the answers to the two questions from the PASE assessment tool38—“How many days over the past seven days did you take a walk for at least 10 min continuously to get to and from places? For example, for walking to shopping, walking to work, etc.?”, and “On average, how many hours per day did you spend walking?” Total hours of walking in the last week were calculated by multiplying the daily average number of hours spent walking by the corresponding number of days.

Total hours of cycling in the last week were constructed based on the answers to the two questions adapted from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Physical Activity Questionnaire40—“How many days over the past seven days did you bike for at least 10 min continuously to get to and from places?”, and “On average, how many hours per day did you bike?” Total hours of cycling in the last week were calculated by multiplying the daily average number of hours spent biking by the corresponding number of days.

We calculated last week’s leisure PA score, transportation PA score, household PA score, and total PA score for each survey participant based on their answers to the assessment questions. Higher scores represent higher levels of PA in older adults.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics for the quantity of greenery, participant demographic information, and PA are listed. In this study, the quantity of greenery was referred to as the streetscape GVI within 500 m of the participant’s home address. Participants’ demographic information contained age, gender, height, weight, BMI, education level, and household economic income, smoking, drinking. PA contained transportation PA, leisure PA, household PA, and total PA. For quantitative variables, mean and standard deviation (SD) values were reported. For categorical variables, percentages were reported. ANOVA and Chi-square tests were performed to test whether the differences between variables are significant. The association between the street greenery and participants’ PA was analyzed by Spearman correlation. When the p-value was less than 0.05, it was considered to be correlational and significant.

Multilevel linear regression models were used to explore independent associations between street greenery around residences and PA among older adults. Two models were successively used for the analysis. Model 1 included only all individual covariates: age, gender, height, weight, smoking, drinking, household income, and education level, and Model 2 further added the quantity of street greenery. Standardized β, 95% confidence intervals (CI), and adjusted R2 were reported for the models. All statistical procedures were performed in SPSS 27.0 and significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all participants. A majority of the participants were composed by females (60.94%). The mean age of the sample was 71.99 (SD = 7.06). The mean height and mean weight of all participants were 162.38 cm (SD = 7.78) and 63.52 kg (SD = 9.86), respectively. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 24.07 kg/m2 (SD = 3.20). In addition, a large percentage of participants (32.7%) had an annual household income of less than or equal to 10,000 yuan. Only 5.7% of the participants had annual household incomes greater than or equal to 160,000 yuan. More than one-half (n = 669; 50.5%) of the participants’ education level was college. A rather small proportions of these participants were current smokers (7.4%) and drinkers (8.0%). ANOVA showed that males were significantly higher than females in age, height, and weight (all p < 0.001), but BMI was not significantly different between genders (p = 0.896). Moreover, chi-square tests indicated that gender was significantly associated with annual household income, education level, smoking, and drinking status (all p < 0.001), suggesting notable demographic and socioeconomic differences by gender among this sample.

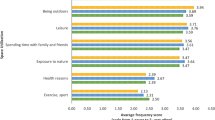

Table 2 shows the descriptive information for the quantity of street greenery and PA. As shown in Table 2, the average quality of street greenery was 0.25 (SD = 0.07). Regarding PA, the total PA score among all participants was 102.99 (SD = 61.91), with the highest component being household PA (43.67 ± 34.50), followed by leisure PA (33.04 ± 32.17) and transportation PA (26.28 ± 23.80). Among leisure PA, LPA was the largest contributor (17.20 ± 19.81). Gender differences were evident in several PA dimensions. Males had significantly lower MPA and household PA compared to females (p < 0.001), but showed no significant differences in street greenery exposure. These patterns may reflect traditional gender roles in household labor and preferences for activity types.

Table 3 presents the results of the correlation analysis between participants’ PA scores and street greenery. Street greenery was significantly and positively correlated with transportation PA (p < 0.05), particularly with cycling (p < 0.01). This relationship was more pronounced among female participants (p < 0.01), suggesting that women may be more sensitive to environmental aesthetics during cycling. However, no significant correlations were observed between street greenery and leisure PA, household PA, or total PA.

Table 4 shows the results of the multilevel linear regression models. Controlling for sociodemographic factors, street greenery was significantly associated with transportation PA (β = 0.08, p < 0.01), indicating that higher greenery levels may encourage walking or cycling as transport. No such associations were found for leisure PA (β = − 0.02, p > 0.05) or household PA (β = − 0.04, p > 0.05), suggesting that environmental greenery may have a selective effect on PA type. These results highlight the domain-specific role of street greenery in promoting transportation PA rather than recreational or domestic activities.

Among covariates, age was negatively associated with all PA types, while education level was inversely associated with both transportation and leisure PA, possibly reflecting more sedentary lifestyles among the more educated. Gender was positively associated with household PA, with females reporting significantly higher scores.

Discussion

This study objectively assessed street greenery exposure at eye level using Baidu Street View images and deep learning techniques. It investigated the association between street greenery and various types of PA among older adults. The results revealed a significant positive correlation between street greenery within a 500 m residential buffer and transportation PA among Chinese older adults. However, no significant associations were found between street greenery and leisure or household PA.

These findings reinforce the notion that urban green spaces positively influence PA in older adults41,42. A previous cross-sectional study conducted in Shanghai, China, demonstrated that higher street greenery levels were associated with increased total PA and active transportation among older adults43. Similarly, a study in Hong Kong used Google Street View images to evaluate both the quantity and quality of street greenery and found positive associations with time spent in recreational physical activities, such as walking, jogging, and cycling44. As another densely populated metropolis, Beijing shares similarities with Shanghai and Hong Kong. The present study further highlights the beneficial role of street greenery in promoting PA among older residents in high-density urban environments. Previous research has shown that well-designed green spaces can offer a safe and comfortable environment that encourages outdoor activity among older adults45. An international comparative study examining the relationship between green spaces and outdoor recreation among older adults in cities such as Sydney, Singapore, and Dhaka found a positive association between high-quality green spaces and walking activity46. These findings highlight the need to integrate green space planning into urban development strategies to support healthy aging. However, it is essential to consider that cultural factors, climatic conditions, and urban planning practices vary across countries and regions, potentially influencing how older adults utilize green spaces. Therefore, designing green spaces that are tailored to the local needs and behavioral habits of older adults is crucial to maximizing their potential to promote PA.

Regarding different types of PA, the main findings of this study revealed a significant association between exposure to street greenery and transportation PA among older adults. This aligns with the findings of Schoner et al.47 who reported that higher levels of tree cover are associated with increased engagement in active transportation, such as walking and cycling. In high-density urban areas like Beijing, cycling and walking are the primary modes of transportation PA and constitute the major sources of daily activity for older adults. Research has shown that tree-lined streets are more likely to promote active transportation behaviors, such as walking and biking, than parks48. Therefore, greater exposure to street greenery may be more effective in promoting transportation PA among this population. However, in the present correlation analysis, street greenery was significantly and positively associated with bicycling but not with walking. Moreover, a systematic review and meta-analysis found no significant association between greenery or aesthetically pleasing landscaping and transient walking49. One possible explanation is that older adults may choose different forms of transportation-based PA depending on the urban and cultural context. Variations in the methods used to assess green space and PA may also contribute to inconsistent findings.

The analyses in this study showed no significant correlation between street greenery and leisure PA among older adults. Similarly, a previous cross-sectional study conducted in the United Kingdom also reported no correlation between urban green space and leisure PA among middle-aged and older adults50. In contrast, Lu et al.44 observed a positive association between street greenery and leisure PA. These inconsistent findings may stem from factors such as differences in study populations, geographic regions, and the extent to which potential confounders were controlled across studies. Moreover, the leisure PA assessed in this study primarily included physical exercises such as running, swimming, and dancing. These activities are influenced by a variety of environmental factors, including perceived safety, environmental aesthetics, and the availability of fitness facilities, all of which can shape individuals’ engagement in PA51,52. Since this study focused solely on street greenery as an environmental factor, future research should incorporate additional environmental variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of determinants influencing leisure PA.

Green spaces are not only linked to residents’ PA behaviors, but there is also growing evidence indicating their broader health benefits53,54,55. A systematic review demonstrated that green spaces are positively associated with both increased PA and improved health outcomes, such as reduced risks of mental health disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and mortality56. For mental health, Wang et al.57 found that higher residential greenery was associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms in older adults. Regarding physical health, Yang et al.58 reported that residing in greener areas was linked to healthier blood lipid profiles, particularly among women and older adults. Although the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, current research proposes that green spaces may improve health through various pathways, including improved air quality, increased PA, enhanced social cohesion, and stress reduction. Notably, PA may serve as a key mediator in the relationship between green space and health outcomes59. The results of the correlation between street greenery and PA in this study may also help to further explain the mechanism of green space on health. Future research could further analyze the mechanisms by which green space affects the health of older adults based on the PA perspective.

The strength of this study is the use of Baidu Street View images combined with deep learning techniques to assess street greenery around participants’ residences. This method provides a more realistic and human-centered measure of green space exposure, aligning closely with pedestrians’ visual perception, and offers improved accuracy and reliability compared to traditional assessment methods. Future studies could incorporate multi-source data (e.g., NDVI) to examine how perceived and objective measures of greenery differentially affect PA. This approach could enhance our understanding of environmental influences and inform more effective urban planning strategies. Moreover, this study comprehensively explored the association between street greenery and various types of PA among older adults. These findings are valuable for the targeted design of green streetscapes to promote PA and enhance the quality of life in aging populations.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design prevents causal inference and only allows for the identification of associations. Longitudinal cohort studies and experimental research are needed to further explore the mechanisms underlying the relationship between street greenery and PA. Second, the study focused exclusively on older adults aged 60 years and above, without including other age groups. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported PA is another limitation. Future studies should consider expanding the sample size and incorporating objective measures of PA to examine the association between street greenery and PA across different age groups. Third, the exposure assessment may be affected by the Uncertain Geographic Context Problem60, as it relies solely on a 500-m residential buffer, which may not capture the full range of participants’ environmental exposures due to their mobility beyond the home area. Future studies should consider activity space–based approaches to more accurately measure environmental exposure.

Conclusion

This study revealed a significant association between residential street greenery and transportation PA among older adults in China. Specifically, enhancing street-level greenery, such as planting trees along sidewalks and creating safe and pleasant walking and cycling environments, may effectively promote active transportation behaviors among older adults. Unlike traditional studies that focus on parks or use coarse vegetation indices, this study employed street-level greenery data derived from Baidu Street View images and deep learning techniques, providing a more accurate representation of older adults’ actual visual exposure to greenery. These findings highlight the importance of distinguishing between different PA domains when evaluating environmental influences and suggest that street greenery plays a particularly critical role in facilitating transportation PA. The results provide novel evidence to support urban planning initiatives aimed at developing age-friendly environments.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

He, W., Goodkind, D. & Kowal, P. R. An Aging World: 2015 (United States Census Bureau Washington, 2016).

Hanmo, Y. Dynamic trend of China’s population ageing and new characteristics of the elderly. Popul. Res. 46, 104–116 (2022).

Mooney, S. J. et al. Neighborhood disorder and physical activity among older adults: A longitudinal study. J. Urban Health 94, 30–42 (2017).

Boakye, K. A., Amram, O., Schuna, J. M. Jr., Duncan, G. E. & Hystad, P. GPS-based built environment measures associated with adult physical activity. Health Place 70, 102602 (2021).

Laddu, D., Paluch, A. E. & LaMonte, M. J. The role of the built environment in promoting movement and physical activity across the lifespan: Implications for public health. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 64, 33–40 (2021).

Organization, W. H. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World (World Health Organization, 2019).

Moreno-Agostino, D. et al. The impact of physical activity on healthy ageing trajectories: Evidence from eight cohort studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 17, 1–12 (2020).

Xiao, Y., Miao, S., Zhang, Y., Chen, H. & Wu, W. Exploring the health effects of neighborhood greenness on Lilong residents in Shanghai. Urban For. Urban Green. 66, 127383 (2021).

He, H., Lin, X., Yang, Y. & Lu, Y. Association of street greenery and physical activity in older adults: A novel study using pedestrian-centered photographs. Urban For. Urban Green. 55, 126789 (2020).

Deng, Y., Liang, J. & Chen, Q. Greenway interventions effectively enhance physical activity levels—A systematic review with meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 11, 1268502 (2023).

Beyer, K. M. et al. Exposure to neighborhood green space and mental health: Evidence from the survey of the health of Wisconsin. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11, 3453–3472 (2014).

Carmen, R. et al. Keep it real: Selecting realistic sets of urban green space indicators. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 095001 (2020).

De Vries, S., Verheij, R. A., Groenewegen, P. P. & Spreeuwenberg, P. Natural environments—Healthy environments? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between greenspace and health. Environ. Plan. A 35, 1717–1731 (2003).

Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., Groenewegen, P. P., de Vries, S. & Spreeuwenberg, P. Green space, urbanity, and health: How strong is the relation?. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 60, 587–592 (2006).

Rolland, Y. et al. Disability in obese elderly women: Lower limb strength and recreational physical activity. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 1, 1–78 (2007).

Picavet, H. S. J. et al. Greener living environment healthier people?: Exploring green space, physical activity and health in the Doetinchem Cohort Study. Prev. Med. 89, 7–14 (2016).

Zhou, W. et al. The role of residential greenness levels, green land cover types and diversity in overweight/obesity among older adults: A cohort study. Environ. Res. 217, 114854 (2023).

Besser, L. M. & Mitsova, D. P. Neighborhood green land cover and neighborhood-based walking in U.S. older adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 61, e13–e20 (2021).

Xie, B., An, Z., Zheng, Y. & Li, Z. Healthy aging with parks: Association between park accessibility and the health status of older adults in urban China. Sust. Cities Soc. 43, 476–486 (2018).

Klompmaker, J. O. et al. Green space definition affects associations of green space with overweight and physical activity. Environ. Res. 160, 531–540 (2018).

Kaczynski, A. T., Potwarka, L. R. & Saelens, B. E. Association of park size, distance, and features with physical activity in neighborhood parks. Am. J. Public Health 98, 1451–1456 (2008).

Chen, X., Meng, Q., Hu, D., Zhang, L. & Yang, J. Evaluating greenery around streets using Baidu panoramic street view images and the panoramic green view index. Forests 10, 1109 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. Association between street greenery and walking behavior in older adults in Hong Kong. Sust. Cities Soc. 51, 101747 (2019).

Zhang, Z., Yang, S., Zhou, L. & Wang, H. Nonlinear associations between design, land-use features, and active travel. Transport. Res. Part D-Transport. Environ. 136, 104440 (2024).

Wu, J., Wang, B., Ta, N., Zhou, K. & Chai, Y. Does street greenery always promote active travel? Evidence from Beijing. Urban For. Urban Green. 56, 126886 (2020).

Thornton, J. S., Morley, W. N. & Sinha, S. K. Move more, age well: Prescribing physical activity for older adults. CMAJ 197, E59–E67 (2025).

Schwartz, B. D., Liu, H., MacDonald, E. E., Mekari, S. & O’Brien, M. W. Impact of physical activity and exercise training on health-related quality of life in older adults: an umbrella review. Geroscience https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-024-01493-6 (2025).

Yu, H., An, R. & Andrade, F. ambient fine particulate matter air pollution and physical activity: A longitudinal study of university retirees in Beijing. China. Am. J. Health. Behav. 41, 401–410 (2017).

Zhao, H., Shi, J., Qi, X., Wang, X. & Jia, J. In 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 6230–6239.

Hino, A. A., Reis, R. S., Sarmiento, O. L., Parra, D. C. & Brownson, R. C. The built environment and recreational physical activity among adults in Curitiba. Brazil. Prev. Med. 52, 419–422 (2011).

Florindo, A. A. et al. Mix of destinations and sedentary behavior among Brazilian adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 21, 1–7 (2021).

Sarkar, C. et al. Environmental correlates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 96 779 participants from the UK Biobank: A cross-sectional, observational study. Lancet Planet. Health 3, e478–e490 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Assessing street-level urban greenery using Google Street View and a modified green view index. Urban For. Urban Green. 14, 675–685 (2015).

Lu, Y. The association of urban greenness and walking behavior: Using google street view and deep learning techniques to estimate residents’ exposure to urban greenness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 1576 (2018).

Helbich, M. et al. Using deep learning to examine street view green and blue spaces and their associations with geriatric depression in Beijing. China. Environ. Int. 126, 107–117 (2019).

Dong, R., Zhang, Y. & Zhao, J. How green are the streets within the sixth ring road of Beijing? An analysis based on tencent street view pictures and the green view index. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 1367 (2018).

Yu, H. J., Zhu, W. M., Qiu, J. & Zhang, C. G. Physical activity scale for elderly (PASE): A cross-validation study for Chinese older adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 44, 647–647 (2012).

Vaughan, K. & Miller, W. C. Validity and reliability of the Chinese translation of the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE). Disabil. Rehabil. 35, 191–197 (2013).

Ngai, S. P., Cheung, R. T., Lam, P. L., Chiu, J. K. & Fung, E. Y. Validation and reliability of the physical activity scale for the elderly in Chinese population. J. Rehabil. Med. 44, 462–465 (2012).

Prevention, C. F. D. C. A. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Physical Activity Questionnaire (PAQ), 2019–2020, <https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/default.aspx?BeginYear=2019> (2019).

Song, Y., Li, H. & Yu, H. Effects of green space on physical activity and body weight status among Chinese adults: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 11, 1198439 (2023).

Feng, X., Toms, R. & Astell-Burt, T. Association between green space, outdoor leisure time and physical activity. Urban For. Urban Green. 66, 127349 (2021).

Xiao, Y., Miao, S., Zhang, Y., Xie, B. & Wu, W. Exploring the associations between neighborhood greenness and level of physical activity of older adults in Shanghai. Urban For. Urban Green. 24, 101312 (2022).

Lu, Y. Using Google Street View to investigate the association between street greenery and physical activity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 191, 103435 (2019).

Juul, V. & Nordbo, E. C. A. Examining activity-friendly neighborhoods in the Norwegian context: Green space and walkability in relation to physical activity and the moderating role of perceived safety. BMC Public Health 23, 259 (2023).

Shuvo, F. K., Feng, X. & Astell-Burt, T. Urban green space quality and older adult recreation: An international comparison. Cities Health 5, 329–349 (2021).

Schoner, J. et al. Bringing health into transportation and land use scenario planning: Creating a National Public Health Assessment Model (N-PHAM). J. Transp. Health 10, 401–418 (2018).

Vich, G., Marquet, O. & Miralles-Guasch, C. Green streetscape and walking: Exploring active mobility patterns in dense and compact cities. J. Transp. Health 12, 50–59 (2019).

Cerin, E., Nathan, A., van Cauwenberg, J., Barnett, D. W. & Barnett, A. The neighbourhood physical environment and active travel in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 14, 15 (2017).

Hillsdon, M., Panter, J., Foster, C. & Jones, A. The relationship between access and quality of urban green space with population physical activity. Public Health 120, 1127–1132 (2006).

Brownson, R. C., Hoehner, C. M., Day, K., Forsyth, A. & Sallis, J. F. Measuring the built environment for physical activity: state of the science. Am. J. Prev. Med. 36, S99-123.e112 (2009).

Zhang, Y. et al. The impact of interventions in the built environment on physical activity levels: A systematic umbrella review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 19, 156 (2022).

Hunter, R. F. et al. Advancing urban green and blue space contributions to public health. Lancet Public Health 8, e735–e742 (2023).

Barboza, E. P. et al. Green space and mortality in European cities: A health impact assessment study. Lancet Planet. Health 5, e718–e730 (2021).

Ali, M. J., Rahaman, M. & Hossain, S. I. Urban green spaces for elderly human health: A planning model for healthy city living. Land Use Pol. 114, 105970 (2022).

James, P., Banay, R. F., Hart, J. E. & Laden, F. A review of the health benefits of greenness. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2, 131–142 (2015).

Wang, P. et al. Association between residential greenness and depression symptoms in Chinese community-dwelling older adults. Environ. Res. 243, 117869 (2024).

Yang, B. Y. et al. Residential greenness and blood lipids in urban-dwelling adults: The 33 Communities Chinese Health Study. Environ. Pollut. 250, 14–22 (2019).

Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., de Vries, S. & Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 35, 207–228 (2014).

Kwan, M.-P. The uncertain geographic context problem. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 102, 958–968 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of all the individuals who have contributed to this study. We thank the study staff and participants.

Funding

This study was supported by the Beijing Social Science Foundation of China (21YTA009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yiling Song: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Formal analysis; Mingzhong Zhou: Methodology, Data curation; Jiale Tan: Methodology; Jiali Cheng: Investigation; Yangyang Wang: Data curation; Xiaolu Feng: Writing—review and editing; Hongjun Yu: Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experimental protocol for involving humans was following the national/ international/institutional boards and the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Tsinghua University Institutional Review Board (No.20110170). All the participants gave written informed consent before completing the survey. Confidentiality of participants’ information was guaranteed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, Y., Zhou, M., Tan, J. et al. Association between street greenery and physical activity among Chinese older adults in Beijing, China. Sci Rep 15, 19509 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03050-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03050-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Systematic review of nonlinear associations between the built environment and walking in older adults

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

Exploring the spatial heterogeneity of micro-mobility ownership based on the geographically weighted Poisson regression model: an empirical study from a small and medium-sized plain city

Transportation (2025)