Abstract

Diabetes-a life style based chronic metabolic disease if left untreated and unmanaged can lead to various complications among diabetics. To improve the health-related quality of life of diabetics, health care providers are classically placed to present suitable interventions. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the effect of pharmacist-led educational intervention on the diabetic patient-reported quality of life upon all the domains of EQ-5D. The study subjects selected for the present study were divided among two equal study arms after being recruited from the hospitals randomly. The controlled group consisted of 200 diabetic patients getting regular treatment from the hospitals. Whereas, the interventional group comprised of those 200 diabetic patients who were receiving the pharmacist collaborative care from DMTAC clinics along with the routine diabetic management and treatment. The study duration was of 1 year and consisted of two follow up visits for both study arms. A generic health related quality of life tool EQ-5D was used for exploring and examining the study data. However, to determine the setbacks in all the individual EQ-5D domains and VAS average scores involving ANOVA and T test analysis have been used. The mean glycated haemoglobin-HbA1c was decreased to 1.44% in control group, whereas, a decrease of 2.84% was seen in interventional study arm. A statistically significant betterment in glycated haemoglobin level was seen in the interventional study arm i.e., p < 0.05. However, all the domains of the questionnaire-EQ-5D 5 L conferred significant association with the health related quality of life parameters (p < 0.05). Moreover, in control study arm a statistically significant enhancement is seen related to average scores of health related quality of life reported by patients on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) from 55.89 ± 7.52 to 64.86 ± 5.04. Moreover, the average scores have been ranged from 54.45 ± 8.81 to 72.23 ± 6.41 among interventional study arm, presenting the statistically significant values i.e., F statistics 118.67 (1, 292) along with p < 0.001. The effect of pharmacist involvement in the form of intervention provision presented a positive improvement and statistically significant enhancement on every domain of the questionnaire-EQ-5D. The pharmacist collaborative care in the form of intervention turned out effective in enhancing the patient reported quality of life as well as in improving glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of non-infectious and lifestyle modification related diseases is continuously increasing in various low and middle high-income countries all over the globe1.

The rapid increase in the prevalence of obesity is the major cause of downfall upon public health and is accountable for numerous lifestyle modification related diseases2. Overweight and obesity are one of the major public health related issues that are considered to be the main risk factor for diabetes mellitus type 23. According to the statistics presented by WHO, the diabetes prevalence is increasing rapidly worldwide. Specifically, the prevalence of diabetes in adults is enhancing rapidly and is estimated to be raised upto 642 million globally by 20404.

In Malaysia, as per the statistics shared by Ministry of Health (Elderly Health) in National Health and Morbidity Survey 2018 the total prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) (Patient-reported diabetes) was 18.9%5. The lifestyle and dietary modifications of the patients are directly related to the onset and progression of many chronic diseases, mainly diabetes mellitus6. In diabetics, the main health related issues like constantly elevated blood glucose, poorly controlled diabetes are directly related to physical activity and lifestyle modifications7.

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease that directly influence every domain of HRQoL- patient reported health related quality of life8. Therefore, uncontrolled or poorly controlled blood glucose of diabetics leads to reduction in patient reported quality of life9. A significant reduction in glycated haemoglobin-HbA1c is directly associated to the enhancement in patient reported quality of life of diabetics10. Research studies have proved the effectiveness of educating patients and the impact of compliance regarding medication and diabetic devices in proper management of diabetes mellitus11. Numerous research studies worldwide have proved the importance of pharmacist involvement in enhancing the patient compliance and adherence to medication therapy. Thus, resulting in improved clinical outcomes of diabetes12.

It has been proved with clinical evidences that the alliance of pharmacists with doctors and physicians results in statistically significant enhancement of glycaemic control in diabetics9,10,11. The health system of Malaysia is considered among the top health-care systems worldwide. Thus, the pharmacists are in direct collaboration with medical practitioners (physicians) in hospitals nationwide through Diabetes Medication Therapy Adherence Clinic (DMTAC). In Malaysian healthcare systems, the medical practitioners (physicians) prescribe the most suitable medication regime that would be followed by intervention provided by the pharmacist to the diabetic patient. The pharmacist led intervention involves instructing patient regarding basic concepts of diabetes mellitus, the medication and dosage regime along with the proper usage technique and storage conditions for insulin and related devices.

Numerous methods can be utilized to estimate the clinical outcomes of rational therapy provided to patients for proper management of diabetes mellitus. Health related quality of life (HRQoL) evaluation is among the leading technique to estimate the disease management outcomes for a particular regimen. It utilizes the patient self-reporting and self-evaluation of the patient health status. However, it is believed that it could be affected by the differences in patient’s understanding or self-observations of the disease along with patient’s own beliefs and expectations regarding diabetes13. The health-related quality of life reported by patients can be evaluated by multiple domains. The prime domains include; Physical Health measurement, Social Relations measurement, the sense of independence level, Psychological level measurement, social quality of life measurement as well as the quality of life measures associated with religion, personal beliefs14.

Multiple research studies have presented the evidence that health related quality of life is substantially reduced by the diabetes mellitus. But the influence of other demographic variables upon the incidence of diabetes mellitus are yet to be evaluated15. However, some variables i.e., type of diabetes mellitus, time duration of diabetes, insulin utilization and clinical complications associated with diabetes have direct effect upon the quality of life of diabetic patients16.

Worldwide, various research study tools are validated after construction to access the health related quality of life-patient reported during chronic diseases. The most important among these are; WHO-QoL, SF-36 and EQ-5D tools14. The easiest research study tool to obtain and utilize for evaluating patient reported-health related quality of life during all chronic diseases is EQ-5D. It is designed to access the physical characteristics, mental level, social staging as well as mobility characteristics of the targeted patients17. The above mentioned study tool (EQ-5D) has been validated and utilized in multiple studies globally, to access the quality of life of patients (patient reported) through various chronic diseases including cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases (asthma), metabolic diseases mainly diabetes mellitus as well as various neurological complications18]– [19. The most recent category of EQ-5D present is the version named as; EQ-5D-5 L. It has been evaluated as comparatively better tool regarding ease of use than the previous versions20. It has a brief list of questions that makes it a low time consumption questionnaire for reporting health related quality of life by the patients. The method of keeping a check upon the health related quality of life of patients and other clinical parameters at regular intervals play an important role in substantially enhancing the quality of life of diabetics. However, health-related quality of life parameters and different factors influencing it, differ substantially based upon geographical regions and cultures20. Therefore, utilizing such a brief study tool with short questionnaire has been regarded as very favourable for accessing the patient-reported health-related quality of life.

Thus, the present research study has been directed to determine the patient-reported health-related quality of life along with its association with patient related demographic variables upon the domains of EQ-5D as well as VAS score at various steps.

Methodology

Study population and study approvals

The 2 tertiary health care hospitals from the city Kedah of Malaysia were selected for the present prospective study. It was a non-clinical, randomized control trial (RCT) study.

The present study has been registered as a clinical trial from multi-centred setting, according to WHO requirements with trial number ACTRN12621001128886 on Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR).

Furthermore, the present study had been registered with “National Medical Research Register” presented with protocol number NMRR-17-2381-38042 and was officially approved by local authorities of study centres along with Medical Research and Ethics Committee (MREC) committee, Ministry of Health Malaysia with approval number KKM/NIHSEC/ P18-1307(13). The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the ethical committee. All participants provided written informed consent for their participation in the study. The study was conducted from July 2018 to November 2019 at both of the study sites. During this period, the 2015 edition of the Malaysian Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus served as the standard reference for clinical care and patient management.

The sample size of the present study was calculated based upon the research study conducted by Mubashra et al., in 201621. The calculations were done to compare and analyse the average blood glucose values among both study arms. Approximately 65 study subjects from each study arm were required to determine the differences of 0.80% approximately (8.48% vs. 9.27% level of HbA1c) along with the 80% certainty (power) and using an alpha level of 0.05 and SD is σ = 1.61. The significant value to reject this null hypothesis was considered as 0.05. The independent t-test statistic was used to testify this null hypothesis. The additional dropout rate was considered as 20% thus the sample size was calculated as 80 samples in each study arm.

Procedure and randomization

The recruitment process spanned three to four months, depending on the patient influx at designated hospitals. Initially, 600 eligible patients with type 2 diabetes provided consent through an Informed Consent Form (ICF) and were considered for inclusion. Their details were recorded in Microsoft Excel, where a randomization process was conducted to ensure an unbiased allocation into control and intervention groups. To further reduce selection bias, a second round of randomization was performed within each group, ultimately selecting 200 patients for each.

Patients were eligible for the study if they had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus for at least five years and had an HbA1c level above 8.0%. Based on the required sample size and necessary study approvals, participants were recruited from designated study centers, with 200 diabetic patients enrolled from each hospital. Among them, 100 were assigned to the control group, while the remaining 100 were placed in the intervention group.

However, certain individuals were excluded from the study, including those newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, pregnant women with diabetes, diabetics with HIV or cancer, and patients with incomplete medical records.

To prevent information contamination between the intervention and control groups, Diabetes Medication Therapy Adherence Clinics (DMTAC) services were scheduled exclusively on two designated days per week at all participating hospitals. This scheduling ensured that only patients in the intervention group received pharmacist-led educational sessions on those specific days. Additionally, all physicians managing diabetes care for both study groups were kept informed about the research through the Clinical Research Centre (CRC) of their respective hospitals. This approach eliminated information blindness and minimized potential data contamination.

Patients in the control group consisted of adult diabetic individuals receiving standard outpatient care as per the Malaysian Clinical Practice Guidelines 2015 at the designated study hospitals. In contrast, the intervention group included patients receiving the same standard outpatient care but with additional pharmacist-led educational interventions at the selected hospitals.

The pharmacist-led intervention implemented in this study was based on the standardized framework of the Diabetes Medication Therapy Adherence Clinic (DMTAC), utilized across tertiary hospitals in Malaysia. The intervention was delivered through four structured educational modules during scheduled follow-up visits, focusing on enhancing patients’ knowledge, self-management, and adherence.

Module 1 covered core diabetes education, including signs and symptoms, therapeutic goals (e.g., fasting blood glucose and HbA1c targets), medication adherence, management of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, self-monitoring of blood glucose, proper medication storage, and addressing patient-specific concerns. Module 2 focused on cardiovascular health, providing education on lipid profiles, blood pressure control, and peripheral vascular disease. It also included counseling on cardiovascular medications such as antihypertensives, antiplatelets, and statins, along with their potential side effects.

Module 3 emphasized lifestyle modifications, including the importance of regular physical activity, nutritional guidance, and smoking cessation. It reinforced awareness of hypoglycemic symptoms and promoted healthier behavioral choices. Module 4 addressed macrovascular and microvascular complications of diabetes, with emphasis on prevention, early detection, and appropriate treatment strategies. Practical foot care education and continued support for lifestyle changes were also included.

In addition to education, pharmacists closely monitored clinical parameters (e.g., blood glucose levels) and provided individualized recommendations for medication optimization—including dose titration or therapy adjustments—based on the patient’s glycemic control, tolerance, and adherence. These recommendations were reviewed and implemented by the treating physicians, in line with the 2015 Malaysian Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. While both groups were comparable in terms of baseline therapy (oral medication, insulin, or a combination), over the 6-month and 1-year follow-up periods, changes in medication regimens were more systematically observed in the intervention group. Pharmacists actively reviewed and assessed each patient’s glycemic control and adherence, and where clinically appropriate, recommended medication adjustments (e.g., dose titration or therapy change), which were subsequently approved by the treating physicians.

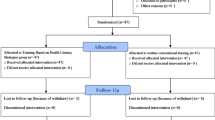

Relevant data were collected separately for both groups—clinical records from diabetic clinics for the control group and from DMTAC services for the intervention group—at each follow-up. At the start of the study, baseline data collection included clinical disease outcomes and Quality of Life (QoL) for each patient. Improvements in clinical outcomes and QoLs were documented during each follow-up visit. To assess changes in QoL relative to baseline, two follow-up visits were conducted for both groups. A complete study flowchart is provided in Fig. 1 below.

The EQ-5D 5 L research tool was used to evaluate the initial health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Following this, follow-up HRQoL results were calculated for both study groups—the control study arm and the interventional study arm—with a 6-month interval between assessments. Two follow-up visits for each group were recorded to assess changes in HRQoL relative to the baseline observations.

Data collection measures

Two distinct tools were employed for collecting patient information data in the study. The first tool utilized was a data collection form, encompassing demographic details of patients and disease-specific clinical outcomes such as Glycated Haemoglobin (HbA1c), Fasting Blood Glucose (FBS), Lipid profile, and the blood pressure status of individuals with diabetes. The second study tool, EQ-5D-5 L, consisted of two sections: the EQ-5D descriptive system featuring five domains, and a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) ranging from 1 to 10020.

EQ-5D-5 L scoring system

The EQ-5D-5 L study tool encompasses five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each domain is graded on a scale of 1 to 5, where “no problems” is assigned 1, “slight problems” receive 2, “moderate problems” are denoted as 3, “severe problems” are rated 4, and “extreme problems” are designated as 5. Patients mark their health status by choosing a number from 1 to 5 for each domain. As per the instructions in the EQ-5D-5 L usage guide, the patient’s data, representing the health demographic profile of individuals with diabetes, is recorded using frequency (%) and number (N%) tabulation for all the domains of EQ-5D-5 L.

However, the scores record of EQ-VAS (visual analogue scale) of diabetic included the overall scoring system for health measure, where diabetics were requested to score their total health status from 0 to 100, upon completion of the rest of the questionnaire. Here, zero indicated worst health status whereas, a Hundred means the best status of health.

Statistical analysis

The data were entered into Microsoft Excel version 2023 and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 (NY, USA). The normality of the numeric variables was confirmed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and further normality was assessed using skewness and kurtosis tests. Descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. For normally distributed data, independent t-tests and one-way ANOVA were used for group comparisons. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons of mean VAS scores were conducted using the Games-Howell procedure to identify statistically significant or non-significant differences between pairs. Fisher’s exact test or the Chi-square test was applied for categorical data. Effect sizes were calculated using Cramer’s V or Phi (φ). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant, with degrees of freedom (df) reported for all statistical tests.

Results

Initially, 600 patients with type 2 diabetes were enrolled in the study and randomly assigned to two groups, with 300 patients in the control group and 300 in the intervention group. However, in the next step, a secondary randomization process was conducted to ensure an unbiased distribution, and 200 patients were selected for each group. As a result, the final baseline study population consisted of 400 diabetic adult patients.

Over the course of the study, only 294 patients successfully completed the required two follow-up visits over the one-year study period. A total of 106 patients (26.6%) dropped out due to various known and unknown reasons. Among them, 59 patients (29.5%) from the control group and 47 patients (23.5%) from the intervention group discontinued their participation. Known reasons for dropout included the transfer of some intervention group patients to other specialized Medication Therapy Adherence Clinics, such as Nephrology, Geriatric, and Respiratory units, due to complications requiring specialized care. Importantly, a portion of the dropouts in the intervention group was due to referral to specialized Medication Therapy Adherence Clinics (e.g., Nephrology, Geriatric, Respiratory), necessitated by emerging complications, rather than a lack of interest or disengagement. The slightly lower dropout rate in the intervention group may indeed reflect the positive influence of the pharmacist-led intervention, which likely enhanced patient engagement and continuity of care. In the control group, some patients were reassigned to Medication Therapy Adherence Clinics where hospital pharmacists provided disease-related education after their condition failed to improve, making them ineligible to continue in the study. Additionally, some control group patients were transferred to different hospitals or relocated to other areas, preventing further follow-up and leading to their exclusion. Figure 1 presents the detail of patient flow throughout the study duration.

EQ-5D 5 L was utilized to record patient’s health related data. After baseline data collection, two follow ups were conducted with a gap of six months. Study duration was of 1 year involving 1 year of data collection period starting from the time of diabetics’ recruitment. During baseline observations, among demographic parameters; time duration of diabetes mellitus among study subjects was the only variable that presented a significant variation i.e., the time duration of diabetes mellitus occurrence was comparatively more in interventional study arm. However, no other demographic variable presented statistically significant variation. Moreover, education status of the study subjects had no significant difference among control and interventional group.

Table 1 demonstrated the demographic variables as well as clinical characteristics of both the study arms.

Study tool- EQ-5D-5 L interpretations

Variations have been detected in every dimension of health related-quality of life reported by diabetics from the initial observations (baseline) to first follow up, and later second follow up.

During baseline survey, no particularly significant difference was seen in quality of life reported by diabetics in both study arms. Statistically non-significant variation in p-value of both study arms demonstrates no particular difference in the study subject’s health related quality of life. Health related quality of life of diabetics is seen to be enhanced as the result of betterment of glycaemic control. During baseline data collection, most of the diabetics reported “severe problem” upon multiple domains of EQ-5D-5 L questionnaire. However, a few study subjects reported “No problem” as well as “Slight problem” upon multiple dimensions of EQ-5D study questionnaire.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the respondents from both control as well as interventional group. Whereas, the differences in multiple dimensions of the questionnaire EQ-5D 5 L in both study arms i.e., control group + interventional group from the baseline observations to the follow-up 1 is presented in Table 2.

At first follow up survey, both control and interventional study arm presented improvement. But, interventional study arm presented better improvements results. Table 3 demonstrated remarkable improvements among every dimension of EQ-5D. Moreover, variations could be observed among “Moderate problems” as well as “Severe problems” dimensions. However, a statistical significant results among these domains presents more improvement in the interventional study arms.

The results from the effect size presents weak positive impact among all dimensions of control and interventional study arms.

During the second follow up visit, comparatively higher improvement has been noted in both control and interventional study arm. However, these betterments were greater in the interventional study arm. Table 4 presents some remarkable improvements in every dimension of EQ-5D. Most importantly, majority of the diabetic’s quality of life improved from “Moderate Problems” to the status “No Problem at all” & “Minor Problems”.

But stronger significant association and positive association on all of these dimensions presents that the betterment in health-related quality of life was greater in the interventional study arm as compared to the controlled study arm.

During baseline survey, no particular difference in health-related quality of life of diabetics has been seen among both of the study arms. Afterwards, during the first follow up survey, a significant difference (p < 0.001) was seen among both study arms. Moreover, the difference was highly statistical significant during second follow up visit.

As shown in Table 5 Degree of freedom in both of the follow-ups indicates the intensity of this significant difference (F-value 19.79 and 118.66 respectively) in the current study.

Results of present study presented that the VAS score was distributed normally for both study arms. Therefore, one-way ANOVA was applied to evaluate the null hypothesis. The findings of VAS score between both study arms revealed that there was non-significant association identified p = 134 F(1,292) = 2.263. To evaluate the equality of variances, no homogeneity of variance as assessed by Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances. Therefore, Post-hoc analysis by means of Games-Howell’s procedure presented that the average of VAS score for control study arm (Mean = 55.89, SD = 7.52) was statistically non-significant as compared to intervention group (Mean = 54.45, SD = 8.81).

The outcomes of the present research study present that glycated haemoglobin-HbA1c has been reducing at a continuous pace among both study arms. However, this reduction was comparatively more significant in the interventional study arm. The health care structure of Malaysia is among the strongest healthcare organizations, globally. The endocrinologists and the physicians prescribe drugs therapies to diabetic’s based upon the recommended guidelines, that results in enhanced diabetic control as well as reduction in HbA1c at a continuous pace. Moreover, the improvement in blood sugar levels of diabetics was comparatively more statistically significant in the interventional study arm, because of the pharmacist involvement in educating patients regarding diabetes management. This is the evidence that clinical outcomes of diabetes mellitus can be improved, if patient’s knowledge regarding diabetes is enhanced with the involvement of pharmacist led educational intervention.

Since, the glycated haemoglobin i.e., HbA1c levels are constantly reducing among diabetics with every visit of the follow up. However, this reduction is statistically greater in the interventional study arm. Eventually, the health-related quality of life would be enhanced as the result of greater control of HbA1c levels. The diabetic clinical outcomes as glycated haemoglobin-HbA1c levels are presented in Table 6.

The present study resulted that quality of life of diabetics can be substantially enhanced by reduction in HbA1c levels. The betterments in the quality of life reported by patients could be seen among every dimension of the questionnaire EQ-5D. This betterment in quality of life was observed in both study arms i.e., controlled study arm as well as interventional study arm. However, the QoL- patient reported was substantially improved in the interventional group as the result of pharmacist led educational intervention.

During baseline survey, dimension of morbility the majority of study subjects lied at “Moderate Problems” along with “Severe Problems”. In controlled study arm, it was 78.2% whereas, interventional study arm had 72.51%. However, during first follow up visit, controlled study arm the scores was reduced to 21.62% with the interventional study arm 24.62%. The frequency of study subjects with moderate and severe problems continued to reduce throughout the year and at second follow up, controlled study arm presented 21.3% whereas it was reduced to 11.12% (p = 0.006) in the interventional study arm. These results prove that the interventional study arm presented much more improvement as compared to the controlled study arm.

During baseline survey, dimension of self care- the study subjects belonging to controlled study arm, who presented “Moderate”, “Severe” along with “unable to wash or dress” were 90.98% among total study subjects. This number was reduced to 26.23% during first follow up visit and further reduced to 17.1% (p < 0.001) during second follow up visit. On the contrary, during baseline survey, it was 92.81% in the interventional study arm and was substantially reduced to 26.21% during first follow up visit. Moreover, it was further decreased to 13.71% during second follow up. Likewise, much betterment has been observed in the Usual activities’ domain.

During base-line survey the controlled study arm study subjects presented the health-related quality of life as “Severe Problems” along with “Unable to do usual activities” were reported to be 40.51%. However, at first follow up visit it was reduced to 18.51% and further decreased to 8.51% at second follow up visit. On the other hand, the interventional group presented 43.81% scores during baseline survey. Moreover, it was reduced to 8.51% upon second follow up and further decreased to 5.91% (p < 0.001) during second follow up visit. These results demonstrate the substantial improvement as compared to the controlled study arm.

Likewise, during baseline survey dimension of discomfort & pain- study subjects who reported “no pain/discomfort” were only 17.1%. However, this number was increased with time. During first follow up visit, the number of study subjects belonging to controlled study arm was raised to 31.91%. However, among interventional study arm the number of study subjects was raised to 43.12%. Moreover, during second follow up visit, the number of study subjects from the control study arm presenting “no pain/ discomfort” were 34.81%. Whereas, interventional study arm has 63.41% (p < 0.001) of diabetics- (almost 2 times to that of control study arm). These results clearly elaborate the effectiveness of pharmacist led intervention upon the health related-quality of life of the diabetic patients.

Likewise, during baseline survey dimension of Anxiety and depression- the study subjects from controlled study arm reporting “Not anxious/depressed” were 38.12% and 35.91% study subjects from the interventional study arm reported the subject cited supra. However, this number was enhanced substantially and second follow up visit presented the percentage of 63.12% at controlled study arm along with 81.72% in the interventional study arm (p = 0.005).

Discussion

The present research study was aimed to determine the impact of pharmacist led educational intervention upon the health-related quality of life reported by diabetes mellitus- type 2 patients by questionnaire EQ-5D-5 L tool. The study has proved that the quality of life of diabetic patients depends directly upon the blood glucose levels. The reduction in glycated haemoglobin levels (HbA1c) of diabetics result in the enhancement of HRQoL of patients and the other way around.

The current study presents that the clinical outcomes i.e., Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels of the diabetics from the interventional study group presented more significant reduction (average decrease of 2.83%) as compared to the diabetics from the controlled study arm (average decrease 1.44%) during a study duration of one year with two follow up visits. Likewise, patient reported quality of life of diabetics presented similar conclusions. The HRQoL (all dimensions of EQ-5D) presented by the diabetics belonging to interventional study arm was substantially more improved as compared to the HRQoL reported by the controlled study arm patients. This betterment in quality of life has been observed starting from the follow up 1, extending till the last follow up visit. The findings of the present study are in line to the results of a research study from Malaysia in 2016 by Butt et al.21, . This has been presented that the involvement of pharmacist in the form of intervention for a duration of six months results in an average reduction of 1.18%±1.362 in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, resulting in a substantial enhancement in the patient reported quality of life of the diabetics. These findings are in accordance with the findings of meta analysis conducted by Collins et al.., in 2011. They presented that a pharmacist led educational intervention through a randomised controlled trial (RCT) for a duration of six months, leads to an average reduction in HbA1c for around 0.96% that automatically leads to the betterment in health-related quality of life of the study subjects22.

The current study aimed to evaluate the impact of pharmacist intervention on the quality of life (QoL) of type 2 diabetic patients using the EQ-5D-5 L questionnaire. Given that disease-specific knowledge among diabetic patients in Malaysia is relatively low (Ching Li et al., 2019), EQ-5D was chosen for its simplicity23. Additionally, no prior studies in Malaysian hospitals have assessed the QoL of diabetic patients or the effectiveness of the DMTAC program. This study provides valuable insights by evaluating the impact of the DMTAC program across different QoL domains through two follow-ups using the EQ-5D questionnaire. The improvement in patient-reported mobility QoL observed in the present study aligns with previous research21,22,23,24. Butt M et al. (2016) reported significant variations in the mobility domain within the intervention group (p = 0.03), whereas no significant difference was observed in the control group (p = 0.35)21. Similarly, our findings indicate a statistically significant improvement in the self-care dimension within the intervention group (p < 0.001), despite a weak effect size (Φ = 0.328).

However, unlike previous studies, which found no significant impact of pharmacist intervention on self-care, our study observed a notable improvement. Butt M et al. (2016) reported a statistically non-significant effect (p = 0.15) on self-care in the intervention group, and Scott et al. also found no significant impact in their study involving pharmacist participation24. This discrepancy suggests that factors unique to the present study—such as the intervention design, patient characteristics, pharmacist engagement, and duration of follow-ups—may have contributed to this improvement.

A key factor influencing this positive outcome may be the structured pharmacist-led educational intervention. By the second follow-up, patients in the intervention group had undergone multiple counseling sessions with pharmacists, leading to increased disease-related knowledge, which, in turn, improved their self-care and overall QoL. In contrast, the control group did not receive such counseling, explaining the lack of similar improvements. This justification is supported by a study conducted in an Australian sample, which highlighted that diabetes knowledge is a crucial factor influencing QoL in diabetic patients25.

Additionally, the current study found a statistically significant enhancement in the QoL dimension of regular activities within the intervention group (p < 0.001), with a weak positive effect observed across both study arms (Φ = 0.248). This finding suggests a modest but meaningful improvement in daily activities. It is consistent with Butt M et al. (2016), who also reported a statistically significant improvement in this domain (p = 0.07)21. However, it contrasts with Johnson CL et al. (2008), who did not observe a significant impact on usual activities26.

The uniqueness of this study lies in its prospective, multi-centered design with a one-year follow-up, distinguishing it from previous research. Our results align with a prospective 12-month follow-up study conducted in Nepal by Upadhyay et al. (2020), which demonstrated that improved patient knowledge directly correlated with better QoL27. Their findings support our conclusion that increased disease awareness leads to QoL enhancement, emphasizing the critical role of pharmacist-led interventions in diabetes management. These findings highlight the importance of structured pharmacist interventions in improving self-care and daily functioning among diabetic patients. Future research should further explore the specific mechanisms driving these improvements and assess the long-term sustainability of pharmacist-led interventions in diabetes care.

The present study found a significant improvement in the pain/discomfort-related quality of life (QoL) in the pharmacist intervention group, although the effect size (Φ = 0.297) suggests a weak positive association. These findings contrast with previous studies, which reported no significant difference between the control and intervention groups in this QoL domain21,24,26. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is the role of pharmacist-led interventions in improving glycemic control and patient self-care, which may have contributed to reduced pain and discomfort.

Diabetic neuropathy and other complications are well-documented contributors to pain and discomfort in diabetic patients28. Previous studies have attributed the lack of significant improvement in this domain to the progressive nature of diabetic neuropathy, which often persists despite pharmacological interventions. However, in the present study, some improvement was observed even in the control group, suggesting that factors beyond pharmacist intervention—such as general disease management and patient adaptation—may have played a role. Nevertheless, the greater improvement in the intervention group underscores the potential benefit of pharmacist-led counseling and education in alleviating diabetes-related pain and discomfort.

By the second follow-up, many patients in the intervention group reported fewer symptoms related to diabetic complications, likely due to improved glycemic control. This aligns with findings from a study conducted in Vietnam by Pham et al. (2020), which reported that diabetic complications negatively impacted health-related QoL, particularly in social and mental health domains29. Our study suggests that by preventing or managing complications through pharmacist interventions, patients may experience improved well-being and reduced discomfort.

The most significant improvements in QoL across all domains, including pain/discomfort, were observed at the fourth follow-up visit, with a statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups. A key factor behind these improvements appears to be the pharmacist-led educational interventions provided through the DMTAC program. These interventions likely promoted lifestyle and dietary modifications, leading to better glycemic control. Studies have shown that improved glycemic control correlates with better QoL. For instance, Svedbo Engström et al. (2019) reported that diabetic patients with higher HbA1c levels experienced lower QoL in most SF-36v2 domains, while those with better glycemic control had improved QoL30. Similarly, Lau et al. (2004) found a positive association between improved HbA1c levels and mental well-being, although they did not observe a significant relationship between glycemic control and physical health31. Overall, these findings suggest that pharmacist-led interventions may play a crucial role in improving diabetes-related pain/discomfort by enhancing glycemic control and promoting self-care behaviors. Future research should further explore the long-term impact of such interventions and investigate whether these improvements persist beyond the study period.

The baseline differences in age and duration of diabetes between the intervention and control groups (p < 0.05) may have influenced the study outcomes, particularly in the pain/discomfort and self-care domains. Older patients and those with a longer duration of diabetes are more likely to experience advanced diabetic complications, including neuropathy, which can impact their perception of pain and overall quality of life (QoL)32. It is possible that participants in the intervention group, despite having a longer diabetes duration on average, benefited more from pharmacist-led counseling, leading to better glycemic control and symptom management over time. Additionally, previous research suggests that older patients may have different coping mechanisms and adherence patterns to disease management strategies, which could contribute to variations in reported QoL improvements. While this study did not statistically adjust for these differences, future research should consider controlling for these variables to better isolate the true effect of pharmacist-led interventions on QoL outcomes.

The betterment in QoL- dimension of anxiety of the current study illustrate a weak positive association (p-0.005 with Φ-0.226) among the interventional and control study arms.

Such observations from the current study are in line with previously published research data21,24,26. Butt M et al.., and colleagues presented the findings of remarkable improvement that was statistically significant (p < 0.001) noted in the study group with pharmacist participation and statistically non-significant in the controlled study arm (p = 0.31)21. Similarly Scott DM et al.., presented the similar findings of improvement in QoL- dimension of anxiety, remarkably as the result of pharmacist intervention upon the diabetics24. Moreover, a one year follow up research study upon the QoL- domain of mental component, depicted the notable betterment in the study group with pharmacist intervention whereas, control study group showed a non-significant association26.

The current study presented average scores of diabetics QoL upon Visual Analogue Scale (VAS scale) utilizing the EQ-5D 5 L form. During baseline observations, the average scores of diabetics belong to controlled study arm were 55.89 ± 7.52, and 54.45 ± 8.81 in patients from the interventional study arm that proved to be statistically not significant (p-0.135, df-2.27). That proves that during baseline observations all the diabetics had almost identical VAS scale. However, during first follow up observations, patient reported QoL average scores upon VAS scale were 59.97 ± 6.79 in the control study arm with 63.11 ± 5.20 in the interventional study arm that was statistical highly significant values (p < 0.001, df-19.79).

In the same way, upon second follow up visit, the VAS scale enhanced upto 72.23 ± 6.41 and 64.86 ± 5.04 (df-118.67) in the interventional study arm and in controlled study arm respectively. This proves that QoL of diabetics upon every follow up visit continuously improves remarkably as the result of pharmacist led educational intervention. Such observations of the VAS scale are supported by notable improvements through every dimension of EQ-5D questionnaire upon pharmacist involvement as intervention provision.

Visual Analogue Scale scores present patient reported QoL ranging from 0 to 100. Diabetics are most likely to rank their health status in better position in the absence of any health issue related to depression/anxiety, normal activity, pain, mobility status and self care parameters in their life. During the beginning of the research study, majority of the study subjects reported health related problems in all dimensions of EQ-5D form. However, by the end of the study, these health-related problems were reduced as the result of pharmacist led intervention. Due to which, at the final follow up observations the patients reported improvement in patient reported QoL upon VAS scale.

A few studies conducted in Korea, Japan, Norway and Malaysia upon type 2 diabetes mellitus utilizing EQ-5D questionnaire to evaluate QoL has scores 91, 84, 85 and 82.46 respectively18,21,33,34. It is a well understood fact that EQ-5D scores level for different regions of the world would be different. But still, quality of life reported by patients is normally influenced by demographic characteristics of the patient including education. This reality should be focused upon during interpretation along with the comparison of QoL values and scores.

The patient’s knowledge regarding the disease is very crucial to obtain accurate results upon the patient reported HRQoL questionnaire. Patient’s poor knowledge about the disease act as a barrier in reporting patient reported quality of life. Majority of the patients have no knowledge about their disease till they start getting its clinical complications, it is the challenging problem of developing countries including Malaysia35.

This randomized controlled trial is one of the first to evaluate the impact of a pharmacist-led intervention on Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) in diabetic patients, focusing on EQ-5D domains and the VAS score. Conducted across two tertiary care hospitals in Malaysia, the study assessed the influence of pharmacist interventions on the HRQoL outcomes of diabetic patients. While the one-year follow-up provided meaningful insights, a longer follow-up period would offer a more comprehensive understanding of disease progression, particularly in relation to diabetic complications. As this study was limited to one state in Malaysia, its findings cannot be generalized to the entire country. Therefore, further research is necessary, with similar studies conducted across all states, to better assess the overall impact of pharmacist-led interventions on HRQoL in diabetes management. Based on the results, several recommendations can enhance future research and healthcare practices. A nationwide, long-term follow-up study should be initiated by the Ministry of Health for a more thorough evaluation. Given the demonstrated effectiveness of pharmacist involvement, the expansion of pharmacist-led interventions, such as the Diabetes Medication Therapy Adherence Clinic (DMTAC) program, should be considered in all hospitals and clinics across Malaysia. Additionally, the potential impact of pharmacist interventions on the HRQoL of patients with other chronic conditions, such as asthma, arthritis, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia, should be explored. Finally, the introduction of MTAC services in private hospitals and clinics could further improve accessibility and effectiveness. This study was conducted with the 2015 edition of the Malaysian Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus as the guiding reference for treatment protocols and clinical decisions36. Future research could explore the impact of more recent updates to clinical guidelines, such as the 2020 CPG, to assess any changes in treatment outcomes and practices.

Conclusion

In general, healthcare professionals are at front line to provide compliance therapy for diabetes mellitus according to the Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) in the health care centres recruited for this study for both study groups. Yet, the participation of pharmacist in the form of interventions results in improved control upon clinical outcomes of diabetes mellitus. The results from this study confirms the effectiveness of DMTAC programme in Malaysia. This study suggests that the diabetics along with the patients would uncontrolled diabetes should be involved in pharmacist led interventional programs to prevent further clinical complications along with enhancement of their health-related quality of life.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR)- ACTRN12621001128886, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and so are not publicly available. The data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of ANZCTR with details: NMRR ID: NMRR-17-2381-38042Universal Trial Number (UTN): U1111-1252-5588 Registration number: ACTRN12621001128886Ethics approval number: KKM/NIHSEC/ P18-1307 (13)URL: https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx? ACTRN=12621001128886 Corresponding author (Dr. Zahid Iqbal) should be contacted to request data of this study.

References

Joshi, R. et al. Task shifting for non-communicable disease management in low and middle income countries–a systematic review. PloS One 9, 8 (2014).

Romieu, I. et al. Energy balance and obesity: what are the main drivers? Cancer Causes Control. 28 (3), 247–258 (2017).

Leitner, D. R. et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes: two diseases with a need for combined treatment strategies-EASO can lead the way. Obes. Facts. 10 (5), 483–492 (2017).

Roglic, G. WHO global report on diabetes: a summary. Int. J. Noncommunicable Dis. 1 (1), 3 (2016).

National Health and Morbidity Survey. : Elderly Health Volume II : Institute for Public Health, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Ministry of Health Malaysia. (NMRR-17-2655-39047) (2018).

da Silva, J. A. et al. Diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and living with a chronic condition: participatory study. BMC Public. Health. 18 (1), 699 (2018).

American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 37 (Supplement 1), S81–90 (2014).

Trikkalinou, A., Papazafiropoulou, A. K. & Melidonis, A. Type 2 diabetes and quality of life. World J. Diabetes. 8 (4), 120 (2017).

Ginsberg, B. H. Factors affecting blood glucose monitoring: sources of errors in measurement. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 3 (4), 903–913 (2009).

Sherwani, S. I., Khan, H. A., Ekhzaimy, A., Masood, A. & Sakharkar, M. K. Significance of HbA1c test in diagnosis and prognosis of diabetic patients. Biomark. Insights. 11, BMI–S38440 (2016).

Jin, J., Sklar, G. E., Oh, V. M. & Li, S. C. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: a review from the patient’s perspective. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 4 (1), 269 (2008).

Iqbal, M. Z., Khan, A. H., Iqbal, M. S. & Sulaiman, S. A. A review of pharmacist-led interventions on diabetes outcomes: an observational analysis to explore diabetes care opportunities for pharmacists. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 11 (4), 299 (2019).

Megari, K. Quality of life in chronic disease patients. Health Psychol. Res. 1, 3 (2013).

World Health Organization. Measuring quality of life: The World Health Organization quality of life instruments (the WHOQOL-100 and the WHOQOL-BREF). WHOQOL-measuring quality of life. (1997).

Kiadaliri, A. A., Najafi, B. & Mirmalek-Sani, M. Quality of life in people with diabetes: a systematic review of studies in Iran. J. Diabetes Metabolic Disorders. 12 (1), 54 (2013).

Jing, X. et al. Related factors of quality of life of type 2 diabetes patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 16 (1), 189 (2018).

Whalley, D. et al. Is the EQ-5D fit for purpose in asthma? Acceptability and content validity from the patient perspective. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 16 (1), 160 (2018).

Lee, W. J., Song, K. H., Noh, J. H., Choi, Y. J. & Jo, M. W. Health-related quality of life using the EuroQol 5D questionnaire in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Korean Med. Sci. 27 (3), 255–260 (2012).

Pinto, É. B., Maso, I., Vilela, R. N., Santos, L. C. & Oliveira-Filho, J. Validation of the EuroQol quality of life questionnaire on stroke victims. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 69 (2B), 320–323 (2011).

EQ-5D-5L. User guide: basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-5L instrument. EuroQol research foundation 2019. Version 3.0 Updated September 2019 (2019).

Butt, M., Ali, A. M., Bakry, M. M. & Mustafa, N. Impact of a pharmacist led diabetes mellitus intervention on HbA1c, medication adherence and quality of life: a randomised controlled study. Saudi Pharm. J. 24 (1), 40–48 (2016).

Collins, C., Limone, B. L., Scholle, J. M. & Coleman, C. I. Effect of pharmacist intervention on glycemic control in diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 92 (2), 145–152 (2011).

Li, L. et al. Diabetes literacy and knowledge among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus attending a primary care clinic in Seremban. Malaysia Malaysian J. Nutr. 25, 3 (2019).

Scott, D. M., Boyd, S. T., Stephan, M., Augustine, S. C. & Reardon, T. P. Outcomes of pharmacist-managed diabetes care services in a community health center. Am. J. Health-System Pharm. 63 (21), 2116–2122 (2006).

Kueh, Y. et al. Modelling of diabetes knowledge, attitudes, self-management, and quality of life: a cross-sectional study with an Australian sample. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 13, 1–11 (2015).

Johnson, C. L. et al. Outcomes from diabetescare: a pharmacist-provided diabetes management service. J. Am. Pharmacists Association. 48 (6), 722–730 (2008).

Upadhyay, D. K. et al. Impact assessment of pharmacist-supervised intervention on health-related quality of life of newly diagnosed diabetics: a pre-post design. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 12 (3), 234–245 (2020).

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus. P. R. Health. Sci. J. ;20, 2 (2013).

Pham, T. et al. Effects of diabetic complications on health-related quality of life impairment in Vietnamese patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 1, 4360804 (2020).

Svedbo et al. Health-related quality of life and glycaemic control among adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes–a nationwide cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 17, 1–11 (2019).

Lau-Chuen-Yen, A. K. et al. Association between glycaemic control and quality of life in diabetes mellitus. J. Postgrad. Med. 50 (3), 189–194 (2004).

Feldman, E. L. et al. Diabetic neuropathy. Nat. Reviews Disease Primers. 5 (1), 41 (2019).

Sakamaki, H. et al. Measurement of HRQL using EQ-5D in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Japan. Value Health. 9 (1), 47–53 (2006).

Solli, O., Stavem, K. & Kristiansen, I. S. Health-related quality of life in diabetes: the associations of complications with EQ-5D scores. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 8 (1), 18 (2010).

Thomas, S., Beh, L. & Nordin, R. B. Health care delivery in Malaysia: changes, challenges and champions. J. Public Health Afr. 2, 2 (2011).

Ministry of Health Malaysia. Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, 5th edition; CPG Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2015 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to convey thanks to the Director General of Health Malaysia for kind permission to publish this study. The authors extend their appreciation to the deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this research work.

Funding

The authors thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through the large Groups Project Under grant number (RGP.2/578/45).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Authors Muhammad Zahid Iqbal and Saad S. Alqahtani designed the study, performed the initial statistical analyses, and wrote the protocol. Authors Muhammad Zahid Iqbal and Saad S. Alqahtani wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors Muhammad Zahid Iqbal and Saad S. Alqahtani managed refined analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iqbal, M.Z., Alqahtani, S.S. Effect of pharmacist led intervention on health related quality of life in diabetic patients assessed using EQ5D domains and visual analogue scale. Sci Rep 15, 21222 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04439-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04439-w