Abstract

This study investigates and compares the impact of various precursor-based reduced graphene oxide (rGO) nanofillers, prepared through chemical and thermal reduction methods on the mechanical properties of E-glass fiber-reinforced epoxy resin composites (GFRPs). Varying amounts of rGO derived from semi-anthracite coal-based graphene oxide (AC-rGO) and graphite-based graphene oxide (Gr-rGO), synthesized via thermal reduction and chemical reduction (AC-GT, Gr-GT, AC-GC, and Gr-GC) into an epoxy resin matrix were dispersed into an epoxy resin matrix. The resulting mixture was infused into E-glass fiber mats to fabricate multiscale composites using vacuum-assisted resin infusion molding technique. The most notable improvements were observed in the thermally reduced graphene synthesized from anthracite coal (AC-rGO)-reinforced GFRPs at a loading of 0.25 phr (parts per hundred resin), with enhancements of 13.4% in flexural strength, 25% in tensile strength, and 21.5% in impact strength. The corresponding improvements for the chemically reduced graphene synthesized from AC-GO, AC-GC-reinforced GFRPs were 9.4%, 23.4%, and 14.1%, respectively. In contrast, for chemically and thermally reduced Gr-rGO-reinforced GFRPs the flexural strength increased by 15.7% and 14.4%, tensile strength by 20% and 22.2%, and impact strength by 16.4% and 7.5%, respectively. A similar trend was observed for interlaminar shear strength (ILSS) testing. To understand the observed differences with various GO precursors, XRD, SEM, and FTIR analyses were conducted. The increment in mechanical properties for AC-rGO-reinforced GFRP is almost equivalent to or greater than Gr-rGO-reinforced GFRP, regardless of the synthesis method used. The enhanced mechanical properties, including high strength, lightweight characteristics, and cost-effectiveness, are essential for a range of applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

E-Glass fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRPs) composites, known for their exceptional mechanical attributes and versatile design capabilities, have found widespread utilization across critical engineering sectors, including aerospace, marine, wind turbine blade production, civil engineering, and the automotive industry1,2. Conventional GFRPs face a range of typical challenges stemming from the incongruity in physical and interfacial characteristics between the binding polymer matrices and the fabric constituents. While there may be a moderate enhancement in mechanical strength, this is offset by reduced toughness and heightened vulnerability to impacts, potentially leading to sudden catastrophic failure due to weak interfacial adhesion and the presence of interfacial flaws3. Furthermore, the rapid deterioration arises from disparities in the thermal expansion coefficients of the matrix and fibers, while substantial manufacturing expenses can also pose additional constraints4.

Also, epoxy resins and hardeners serve as the primary choice for the matrix in GFRPs due to their superior attributes, including high stiffness, exceptional strength, excellent thermal stability, and remarkable chemical and corrosion resistance5. However, a notable drawback of epoxy is its inherent tendency towards low fracture toughness6. Therefore, the fiber-based composites industry employs various nanofillers to transfer stress from the matrix to the nanofiller. This can be achieved by simply incorporating a small concentration of nanofillers, thereby augmenting their mechanical characteristics7,8.

Graphene is considered an excellent choice as a filler for epoxy because it forms a strong bond with epoxy, thanks to its beneficial functional groups like hydroxyl and carboxyl and also the strong pi-pi interactions owing to its hexagonal aromatic structure. Additionally, graphene possesses exceptional high-temperature properties, maintaining its strength and stiffness even at temperatures as high as 2500 °K9. Shabberhussain et al.10 showed that the addition of graphene nanoplatelets to GFRP composites fabricated using the hand layup method increased tensile strength and flexural strength, while composites fabricated using the vacuum bag process exhibited reduced tensile properties due to poor adhesion. Cakir et al.11 conducted a study to investigate the impact of different concentrations of graphene nanoparticles (GNP) in epoxy adhesive on the shear and flexural properties of bonded joints in GFRP. The results revealed that the incorporation of 0.3 wt% GNP led to significantly improved load transfer between the adherents, resulting in a remarkable 145% increase in shear strength. Additionally, samples containing 0.2 wt% GNP showed a substantial 100% enhancement in flexural strength. From the literature, it is quite evident that graphene serves as an excellent nanofiller.

The modified Hummers’ method, utilizing graphite as the precursor, has been the prevailing commercially employed technique for synthesizing graphene12,13,14,15,16. Al-Mufti et al.17 employed graphite as a precursor for GO, and further subjecting GO to thermal treatment at 800°C to reduce GO and produce rGO. FTIR analysis revealed the disappearance of certain oxygen-containing functional groups in rGO compared to GO. Additionally, some peaks in the rGO spectrum were flattened, indicating the removal of carbonyl groups. In18, they have also subjected GO to single thermal reduction (STR) and double thermal reduction (DTR) processes in which samples were exposed to temperatures of 500, 700, and 900 °C for 5 min. The prime focus was to check the electrical conductivity of rGO and the results indicated that the DTR process improved the electrical conductivity of rGO samples. However, with the increasing cost of graphite and its regional limitations, researchers have been investigating alternative, easily accessible precursors like coal, biomass, etc19. Moreover, the modified Hummers’ method is tedious, demanding harsh chemicals, leading to the emission of harmful gases like NOx, ClOx, and few carcinogens. To address these concerns, Lee and Mahajan20 have developed a simplified process to synthesize GO that uses semi-anthracite coal as a precursor and a single acid (HNO3) for oxidative scissoring of the sp2 graphitic domains from the coal edges. More recently, Garg et al.21 extended this process to bituminous coal (BC) obtained from one of the mines in India and showed that the original recipe for semi-anthracite coal needs fine-tuning for optimal production of GO. In the previous work21,22, the potential of coal-derived GO obtained from different ranks of coal as a nanofiller in enhancing the mechanical properties of E-glass fiber based epoxy composites has been shown. The incorporation of AC-GO (semi-anthracite coal derived GO) as a nanofiller in GFRP composites led to notable enhancements in their mechanical characteristics. The tensile strength and modulus experienced a significant increase of 18.3% and 30.9%, while the flexural strength and modulus rose by 22.7% and 25.1%, respectively. Furthermore, a slight uptick of 6.7% was noted in the impact strength at a loading of 0.125 phr of AC-GO in GFRP composites. It was concluded that the particle size of GO fillers is crucial for the mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Smaller nanofiller particle sizes, as in BC-GO, can enhance these properties through reinforcement effects, filler-matrix interaction, and particle packing density.

This study builds upon the conclusions of our previous work to investigate the influence of particle size on the mechanical properties of composites synthesized using AC-rGO and Gr-rGO. The performance of a hydrophobic nanofiller (rGO) with a hydrophilic nanofiller (GO) in terms of their dispersion in a hydrophobic matrix, such as hydrophobic epoxy has also been compared. It is hypothesized that a hydrophobic nanofiller in a hydrophobic matrix should reduce interfacial tension between the filler and matrix, leading to better wetting, dispersion, and resulting mechanical strength. Additionally, the impact of chemical and thermal reduction techniques, which are commonly employed to convert GO to rGO on the mechanical properties of the composites are investigated. Thermal reduction is expected to produce higher-quality nanofillers due to fewer residual impurities compared to chemical reduction. Even after thermal reduction, rGO typically retains a small fraction of oxygen-containing functional groups. These groups can form covalent or hydrogen bonds with the polymer matrix, providing interfacial linkages23. Also, the restoration of conjugated π-electron systems during thermal reduction enhances rGO’s ability to interact with aromatic or π-rich polymer matrices24. The latter often involves reducing agents like hydrazine hydrate that can leave behind unwanted byproducts and contaminants. While it is true that thermal and chemical reduction processes largely eliminate oxygen-containing functional groups from the GO surface, these methods offer several advantages that are critical to the objectives of our study. Firstly, the reduction of GO restores its sp² hybridized carbon structure, significantly improving the electrical conductivity and thermal stability of the resulting reduced graphene oxide (rGO). These properties are essential for enhancing the performance of polymer composites in applications where high mechanical strength is required. Secondly, although the reduction process removes a majority of functional groups, residual oxygen-containing groups often remain on the rGO surface. These residual groups can form chemical bonds or non-covalent interactions with the polymer matrix, contributing to interfacial adhesion. Thirdly, the restored graphitic structure facilitates π-π interactions with polymers that possess aromatic backbones, which is another mechanism promoting compatibility with the matrix. Moreover, the rough surface morphology of rGO aids in mechanical interlocking with the polymer chains, enhancing the composite’s mechanical properties. This leads to more uniform load transfer and improves overall composite performance.

This study introduces multiple aspects of novelty, focusing on an integrated examination of particle size, nanofiller chemistry, and processing techniques, which are less frequently addressed together in composite material research. The mechanical properties of different composites containing differently processed nano fillers have been related to their different structures, processing, morphology, and finally to the expected different extent of interfacial bonding.

Materials and methods

Materials

The epoxy resin Araldite CY 230-1and curing agent Aradur HY 951, possessing diglycidyl ether functionality and aliphatic amine functionality respectively, were obtained from Huntsman Advanced Materials. in India. The epoxy resin and curing agent were mixed in a weight ratio of 10:1 as per the manufacturer’s recommended stoichiometry to ensure optimal cross-linking and curing. E-glass fiber mats, sourced from Revex Plasticizers Pvt. Ltd. in India, served as the reinforcing phase in the composite, while graphite powder (98% purity) was sourced from Loba Chemie. AC-rGO was synthesized in-house using a facile one-pot method followed by reduction. Raw chunks of semi-anthracite coal (80% fixed C content), sourced from coalfields in Kashmir, were supplied by SVISPAT Pvt Ltd in Pune, Maharashtra, India. Other chemicals like acetone, hydrochloric acid, hydrofluoric acid, nitric acid, sulphuric acid, sodium nitrate, potassium permanganate, hydrogen peroxide, and hydrazine hydrate were sourced from Merck. Double distilled water was utilized to prepare the reagents and for washing purposes during the experiments. All chemicals were used as received without further purification.

Synthesis of coal-derived graphene oxide via one-pot method

The nut-size raw coal was subjected to ball milling to achieve a particle size smaller than 100 μm. To purify the raw coal powder, a mixture of acids, 37% HCl, and 50% HF, along with 500 ml of distilled water, was employed. This mixture was stirred using a magnetic stirrer for 36 h. Afterwards, the mixture was allowed to settle undisturbed for 12 h, leading to the formation of black precipitates at the bottom of the beaker.

Following this, three grams of the purified coal were oxidized using 16 M HNO3 at a temperature of 120°C for 5 h. The resulting solution containing oxidized Coal-GO was then neutralized and subjected to probe sonication for 4 h, after which centrifugation was performed. The resulting AC-GO solution was subsequently dried in an oven at a temperature lower than 60 °C20,21.

Synthesis of graphite-derived GO via modified hummers’ method

The mixture of graphite powder and sodium nitrate (NaNO3) was added to 46 ml of conc. sulphuric acid (H2SO4) which appeared black and viscous. The resulting solution was kept in an ice bath to maintain the temperature below 20 °C and stirred for 4 h. Later, approximately 6 g of potassium permanganate (KMnO4) was introduced to the solution and vigorously stirred for another hour which turned to purplish-brown, indicating the formation of manganese intermediates. Thereafter, 220 ml distilled water was added dropwise, accompanied by continuous stirring (changed to brownish yellow), suggesting successful oxidation. Dropwise addition of 10 ml of 30% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) resulted in a bright yellow solution. Lastly, the solution was washed using 5% hydrochloric acid (HCl) and distilled water. The product was dried in an oven overnight to procure dry powdered GO.

Chemical reduction of AC-GO and Gr-GO

0.3 g of AC-GO/Gr-GO was added to 30 ml of 10% hydrazine hydrate (H6N2O) and sonicated for 10 min. Then the prepared solution was transferred to an autoclave and kept in a muffle furnace for 12 h at 180°C. After the completion of the reaction, the solution was washed several times using distilled water and dried in an oven at 80°C. The obtained final powders were designated as AC-GC (AC-rGO synthesized by chemical reduction) and Gr-GC (Gr-rGO synthesized by chemical reduction).

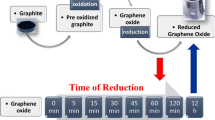

Thermal reduction of AC-GO and Gr-GO

3 g of powdered AC-GO/Gr-GO was taken in a boat-shaped crucible and heated to 800°C for 1 h at a rate of 2 °C/min. Following a dwell time of 1 h at 800°C, the furnace was allowed to cool naturally to room temperature. The whole process was in an atmosphere of 10% N2. The end product was thermally reduced rGOs: AC-GT and or Gr-GT20.

Fabrication of GFRP multiscale composites

Based on previous work22, similarly, the concentration range of rGO are varied and obtained from the two precursors using chemical and thermal reduction (AC-GC, AC-GT, Gr-GC, and Gr-GT) from 0.125 phr (parts per hundred resin) to 0.75 phr in the GFRP composites. The choice of very low rGO loadings (0.125–0.75 phr, i.e., ≈ 0.125–0.75 wt%) is supported by multiple studies showing that modest rGO additions yield strong gains, whereas higher loadings give diminishing returns or dispersion problems. For example, Ejaz et al. found that adding just 0.25 wt% rGO to an epoxy adhesive improved tensile strength by 9.5% and toughness by 128%25. Khabaz-Aghdam et al.26 likewise report that rGO loadings up to 0.5 wt% steadily increase elastic modulus and strength in an epoxy adhesive. Marami et al.27 observed ~ 27% higher lap-shear strength at 0.5 wt% rGO in a biobased epoxy system. In an actual glass-fiber/epoxy composite, Dubey and Panneerselvam showed that 0.75 wt% rGO produced ~ 40% higher tensile strength and ~ 58% higher compressive strength (and similarly large flexural gains) relative to neat epoxy28. Importantly, all these works note that higher loadings ( ≳ 0.5–1 wt%) tend to cause rGO agglomeration or processing difficulties, which cut off further strength improvements. Initially, respective rGOs were dispersed in the epoxy resin and homogenized at 20,000 rpm for 10 min, followed by probe sonication at 80% amplitude for 10 min in an ice bath to allow dissipation of excessive heat. The solution was mechanically stirred at 500 rpm for 10 min. Following this, the hardener was introduced into the mixture. The resulting dispersion was then infused into the VARIM (Vacuum Assisted Resin Infusion Molding). Before the infusion process, the VARIM table underwent cleaning using a cleansing agent, and it was subsequently coated with a mold release agent to prevent sticking.

Following the guidelines set by ASTM standards, two-ply mats were employed for preparing the composites sheet for testing their tensile and flexural properties. For impact testing, specimens were prepared using twelve layers of this mat. For uniform resin distribution, a separator cloth was placed on the top layer of the glass-fiber mat. On top of this, a perforated sheet was situated. To enhance resin flow, a wire mesh was integrated to establish a smooth route. An infusion pipe was positioned over the wire mesh and secured using sealant tape. Furthermore, a breather cloth was utilized once more to form a bridge across the wire mesh, ensuring the resin flowed smoothly. In the concluding phase of the manufacturing process, the complete setup was covered with a lamination sheet and sealed using a sealant tape. A vacuum pump was utilized to maintain a vacuum pressure of around 1 mbar. The resin infusion procedure was carried out with the assistance of the vacuum pump, ensuring that the fiber mat was thoroughly impregnated with the resin. After the infusion, the multiscale composite sheets underwent a curing stage, followed by two separate post-curing phases, each lasting 6 h. The initial post-curing was conducted at a temperature of 23 °C, followed by the second at 60 °C. The general scheme/camera visuals are shown in Figure S1, which represents the protocol followed during the preparation of sheets.

Characterization and mechanical testing

To assess the properties of multiscale composites comprising different rGOs with GFRP, a range of analytical techniques was employed, including FESEM (Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy), XRD (X-Ray Diffraction), and FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy). X-Ray Diffraction analysis (XRD) was conducted using a PANalytical X-ray diffractometer equipped with Ni-filtered Cu Kα radiations (λ = 0.1504 nm). The scanning rate was set at 2 degrees per minute in the 10–90º range, with an applied voltage of 45 kV. Fractographic analysis of fractured composite samples was conducted using a ZEISS field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) with an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. To analyze the functional groups, present in different concentrations within the prepared composites and identify any chemical modifications resulting from the addition of rGOs, a Shimadzu FTIR spectrophotometer (IRTacer-100) was employed. FTIR analysis was conducted by scanning the range of 400–4000 cm− 1. Particle size distribution measurements of the dispersed graphene oxide in deionized water were performed using a dynamic light-scattering method (DLS) with the Zetasizer instrument from Malvern. The composite specimens for mechanical testing, including impact, tensile strength, and flexural strength were prepared following the guidelines outlined in ASTM D 256–02, ASTM D 3039, and ASTM D 790–02, respectively. The tensile strength and flexural strength of the composites were assessed using a Universal Testing Machine (UTM) manufactured by Zwick/Roell in Germany. For impact testing, a Tinius Olsen impact tester (model-IT504) was utilized. To ensure reproducibility, five specimens were prepared and tested for each strength property in all the composites.

Results and discussion

XRD and FTIR of GFRP multiscale composites

The XRD patterns for different rGO nanofillers synthesized from coal-based and graphite-based GO through different routes of reduction (AC-GC, Gr-GC, AC-GT, Gr-GT), along with EGFP (without nanofiller) are shown in Fig. 1a. According to references21] and [22, the XRD patterns of coal-based GO exhibit peaks at 2θ (002) = 23.9° corresponding to the crystalline carbon. Another peak at 2θ = 42.3° observed in AC-GO (synthesized by one-pot method) represented the plane reflection of graphite (100), whereas Gr-GO (synthesized by modified Hummers’ method) exhibits an XRD diffraction peak at around 2θ = 10.19° corresponding to the (002) plane with a d-spacing of 0.86 nm. In Fig. 1a, AC-GC and AC-GT, by contrast, exhibit distinctive peaks at 2θ (002) = 26.5° and 25.2°, respectively, suggesting that the Coal-GO is well-restored to the primary structure of turbostratic graphitic carbons found in purified coals. The 2θ (002) in Gr-GC and Gr-GT are observed at 25° and 26.4°, respectively. The reduced intensity of the C (002) peak in Gr-GC and Gr-GT, in comparison to graphite20, is likely due to the presence of carbonaceous nanomaterials that have not completely transformed into crystalline graphite. This phenomenon is likely linked to the prevalence of sp3 carbon (in-plane defects) on the basal plane introduced during the thermal treatment, during which oxygen functional groups are eliminated20,21. The d-spacing is calculated using Bragg’s Law: nλ = 2dsinθ where, n = 1 (first-order diffraction), λ = 1.5406 Å (Cu Kα radiation). The Table S2 attached below shows the d-spacing calculated for each synthesized composite. From the Table S2, it is quite evident that GO typically shows a higher interlayer spacing (d-spacing) compared to reduced graphene oxide (rGO). This is because the oxidation process introduces oxygen-containing functional groups (such as hydroxyl, epoxy, and carboxyl groups) onto the basal planes and edges of the graphite/coal structure. These groups disrupt the π–π stacking and increase the interlayer distance. For instance, Gr-GO and AC-GO exhibits a greater d-spacing, indicating significant oxidation and exfoliation.

Upon reduction- whether thermal or chemical- many of these oxygen-containing groups are removed, leading to partial restoration of the graphitic structure. As a result, the interlayer spacing decreases due to the re-establishment of π–π interactions and removal of intercalated water or oxygen groups. This is evident from the d-spacing values of the rGO samples, which fall in the range of 3.35–3.56 Å, significantly lower than that of Gr-GO. The slight differences in rGO d-spacing among the samples can be attributed to the type of precursor (graphite vs. coal) and the reduction method used. For example, chemically reduced samples (Gr-GC and AC-GC) retain slightly higher d-spacing compared to thermally reduced Gr-GT and AC-GT, possibly due to incomplete removal of oxygen functionalities or differences in reduction efficiency.

Without any nano reinforcement, the XRD spectrum of EGFP0 shows a clear diffraction peak at 2θ = 19.02°, which is ascribed to residual crystalline silica within the composite material. Since no other distinguishable diffraction peaks were observed in the GFRP composite, it suggests that the composite, lacking nanofillers, possesses an amorphous structure29.

XRD diffractograms of AC-GC, AC-GT (0.25 phr and 0.75 phr of each), Gr-GC, and Gr-GT (0.50 phr and 0.75 phr of each) composites (Fig. 1b and c) when compared with that of GFRP alone (Fig. 1a), clearly show no other distinct peaks corresponding to the crystalline planes of the respective AC-rGO or Gr-rGO. This implies that the incorporation of nanofillers does not influence the degree of crystallinity of the corresponding GFRP composites30. The consistent presence of an identical peak in all GFRP composites, i.e., 2θ = 19.02°, suggests that the morphology of the reinforced GFRPs is predominantly exfoliated indicating that rGO platelets might be far apart from each other. This observation holds true regardless of the specific composition or type of nanofiller employed.

Raman spectroscopy was additionally carried out on the rGO samples. In the Raman spectra of most carbon-based materials, notable peaks are observed, namely the D and G bands located in the range 1327–1350 cm− 1 and 1590–1602 cm− 1, respectively31. The D-band signifies structural imperfections induced by k-point phonons in the A1g symmetry breathing mode, whereas the G-band corresponds to in-plane vibrations of E2g phonons related to sp2 carbon atoms32. In AC-rGO samples (AC-GC and AC-GT) shown in Figure S3, the intensity of the D-band is less than of the G-band, indicating successful restoration of sp2 graphitic carbons during the formation of rGO. However, in the case of Gr-GC, the intensity of the D-band is higher than the G-band which denotes that the sample is highly defective. This may be possibly due to the utilization of H6N2O which even after several washing leaves traces indicating a disordered structure. However, in Gr-GT, the D-band intensity is comparable to the G-band intensity. Oliveira et al.33 reported that the bands on (rGO prepared via thermal reduction of the GO (Gr-GT), spectrum are similar to the GO spectrum, but have low intensities in the G and D bands. It is less intense because of the increased crystallinity related to the deoxygenation of the structure and the decrease of sp3 carbons. The ID/IG ratios estimated from Raman spectra were ~ 0.92 for AC-GC, ~ 0.98 for AC-GT, ~ 0.87 for Gr-GC, and ~ 0.89 for Gr-GT. These values reflect higher defect density in coal-based rGO compared to graphite-based rGO, aligning with their respective mechanical performance trends.

FTIR stands out as a highly favored tool for analyzing mechanistic interpolymer hydrogen bonding. It provides a non-destructive and highly effective means to capture the molecular fingerprint of diverse compositions. The FTIR spectra of cured epoxy/glass fiber composites, both with and without nanofillers at various loadings, are depicted in Fig. 2. For conciseness, only the spectra corresponding to the relevant concentrations are displayed, as the peaks were largely uniform across all samples.

Significantly, the spectra exhibited similarity between composites with and without the nanofiller. This similarity arises from the abundance of functional groups present in both epoxy and glass fiber34, such as epoxides, carbonyls, and hydroxyl groups, as well as few oxygen-based functional groups on graphene surface, leading to overlapping peaks. The intense and wide peaks detected within the range of 3319 cm− 1 to 2910 cm− 1 can be ascribed to the existence of -OH stretch groups. The peaks observed between 1598 cm− 1 to 1715 cm− 1, and 1438 cm− 1 to 1450 cm− 1 are indicative of the bending vibrations of C-H bonds present in the composite material35. AC-GC spectra represent a prominent peak at 1562 cm− 1, AC-GT at 1480 cm− 1, Gr-GC a very slight stretch at 1509 cm− 1, and Gr-GT at 1572 cm− 1 and 1125 cm− 1 which shows C = C stretch, C-H bending, N-O stretch, C = C and C = O stretch respectively highlighting the restoration of conjugation or aromatic structures. These FTIR spectra of rGO nanofillers synthesized from coal and graphite exhibit significantly reduced intensities of functional group peaks, indicating that the thermal or chemical reduction of AC-GO and Gr-GO effectively removes oxygen-containing functional groups. However, the observed difference in reduction efficiency between graphite-based GO and coal-based GO using hydrazine hydrate can be attributed to fundamental differences in their structural and chemical nature. Graphite, being a highly crystalline and ordered carbon source, yields GO with a relatively uniform distribution of oxygen-containing groups, primarily located at the edges and interlayer spaces. These groups are more accessible and easier for hydrazine to reduce, resulting in a more complete elimination of functional groups and restoration of the sp² carbon framework. In contrast, coal-derived GO originates from a more amorphous and heterogeneous carbon matrix, which contains a higher density of defects, disordered carbon regions, and a more complex distribution of oxygen functionalities, including strongly bound hydroxyl and carboxyl groups. These groups are often located at defect sites or within internal pores, making them less accessible to hydrazine. As a result, while graphite-based GO undergoes more efficient and near-complete reduction to form Gr-GC, coal-based GO typically shows only partial deoxygenation to form AC-GC under the same hydrazine treatment conditions. Therefore, FTIR spectra for Gr-GC lack visible peaks.

Tensile and flexural properties of GFRP composites reinforced with AC-GC, Gr-GC, AC-GT, and Gr-GT nanofillers

In this section, the effect of incorporating AC-GC, Gr-GC (synthesized through chemical reduction), AC-GT, and Gr-GT (synthesized through thermal reduction) nanofillers on the mechanical behavior of glass fiber-reinforced polymer composites has been investigated. First, consider the tensile strength and tensile modulus data displayed in Figs. 3 and 4 for AC-GC, Gr-GC, AC-GT, and Gr-GT-based GFRPs with four different loadings of the respective nanofillers ranging from 0.125 phr to 0.75 phr. For both AC-rGO and Gr-rGO, the tensile strength initially increases with an increase in the loading rate, reaching a maximum at 0.25 phr for AC-GC and AC-GT and 0.50 phr for Gr-GC and Gr-GT. Beyond these optimal values, a further increase in the loading rate led to a decrease in tensile strength due to agglomeration of the nanofillers. Agglomeration reduces the exposed surface area of AC-GC, Gr-GC, AC-GT, and Gr-GT, leading to fewer π-π available for bonding with the epoxy matrix and poorer dispersion of particles in the matrix, thereby reducing the efficiency of stress transfer from the matrix to the reinforcing rGOs.

Notably, the incorporation of AC-GC and AC-GT leads to a comparable increase in tensile strength (23.4% and 25%) at the optimal loading of 0.25 phr; for Gr-GC and Gr-GT, this increase is 20% and 22.2% at the optimal loading of 0.50 phr. It is worth noting that tensile strength increased almost similarly regardless of the synthesis method (chemical or thermal reduction) and different precursor, coal or graphite (20–25%). The gain in tensile strength is attributed to the even distribution of rGO within the epoxy resin, facilitating efficient stress transfer from the matrix to the fillers. This phenomenon might also stem from the oxygen functionalities within rGO, albeit very few36. Additionally, the tensile modulus for both AC-rGO and Gr-rGO is also higher than that of GFRP, see Fig. 4, it being 31.7% and 32.8% for 0.25 AC-GC and AC-GT, and 28.7% and 30.2% for 0.50 Gr-GC and Gr-GT.

Interestingly, as the numbers indicate, the relative advantage in the tensile modulus of AC-rGO and Gr-rGO is distinctly higher than the improvement observed for the tensile strength. This increase in tensile modulus can be attributed to the relatively high modulus of the rGO filler and the good interfacial adhesion between the rGO and the epoxy matrix. Good interfacial adhesion may arise from surface chemistry interactions, as well as from mechanical interlocking of the wavy rGO sheets with the epoxy matrix as also reported by Olowojoba et al.37. Also, Tschoppe et al.38 observed a modulus increase of 8.5% in an epoxy composite containing 1.5 wt% of thermally reduced GO and 11.4% in a composite filled with 2 wt% of nitrogen-doped thermally reduced GO. Chetri et al.39 reported the preparation of NMP-functionalized reduced GO nanosheets via one-pot hydrothermal reduction. These nanosheets were subsequently integrated into an epoxy matrix to produce epoxy composites. The enhanced compatibility and interfacial interaction between the epoxy matrix and NMP-functionalized rGO resulted in approximately 28%, 19%, and 51% enhancements in tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and storage modulus, respectively. Figure S2 shows the tensile stress versus % extension curve which shows that the tensile properties tend to increase for both chemical and thermally reduced graphene-based composites with respect to neat GFRP.

Figures 5 and 6 display the data for flexural strength and flexure modulus of the GFRP composites with AC-GC, Gr-GC, AC-GT, and Gr-GT at different loadings.

Similar to tensile properties, the maximum gains in flexural strength and flexure modulus were observed at a loading of 0.25 phr for AC-GC and AC-GT and 0.50 phr for Gr-GC and Gr-GT (see Figs. 5 and 6, respectively). For AC-GC and AC-GT, the flexural strength increased by 9.4% and 13.4%, and for Gr-GC and Gr-GT, the flexural strength increased by 15.7% and 14.4%. The main reason for the gain in flexural strength can be attributed to the planar geometry of rGOs, as the thickness of the sheets is small they create a wrinkled structure that provides better mechanical interlocking with epoxy chains40. The flexural modulus for AC-GC and AC-GT increased by 27.4% and 19.7% whereas for Gr-GC and Gr-GT, this increase was 31.8% and 28.2%. This may be attributed to the strong aromatic interactions (π-π bonding) between the different rGOs and epoxy matrix leading to their varying dispersion in the matrix which synergistically affects the overall moduli. Liu et al.41 developed composites of reduced graphene oxide/polyimide resin (rGO/PI) through hot-pressing, resulting in improved mechanical properties. The rGO nanosheets were synthesized via thermal reduction and easily mixed with PI powders in an aqueous solution using sonication. Compared to pure PI, the optimized rGO/PI resin (1.5 wt%) composite exhibited a 30% increase in tensile strength, 19% in flexural strength, and 27% in impact strength. These enhancements were attributed to the fine dispersion of graphene nanosheets with high specific surface area and strong adhesion between rGO and the matrix. However, with the addition of excess rGO sheets (2 wt%), there is a gradual decrease in strength and modulus, likely due to the sheet loading surpassing the critical level. This leads to undesirable phenomena such as the formation of holes and cracks in the matrix.

Interlaminar shear strength (ILSS) and impact strength of GFRP composites reinforced with AC-GC, Gr-GC, AC-GT, and Gr-GT nanofillers

ILSS is heavily influenced by factors such as fiber-matrix adhesion, manufacturing quality, and the presence of defects like delamination or voids. The ILSS for the rGO based GFRP composites has been calculated by using the formula:

\({\text{ILSS}}\,=\,{\text{3P}}/{\text{4bt}}\)

where, P represents the maximum load applied (N), b is the width of the specimen (mm), and t stands for the thickness of the specimen (mm). Figure 7 depicts the ILSS graphs for all the GFRP composites both with or without nano reinforcements. The ILSS increased by 25.7% and 27.3% for 0.25 phr AC-GC and 0.25 phr AC-GT but for 0.50 phr Gr-GC and 0.50 phr Gr-GT, it increased by 22% and 24% compared to GFRP. The optimized concentration of rGO ensures good dispersion of rGO within the matrix and along fiber-matrix interfaces. This enhances interfacial bonding and restricts crack propagation, leading to a significant increase in ILSS. rGO reinforces the polymer matrix by restricting crack propagation through its high stiffness and strength. Also, rGO’s 2D structure can act as a physical barrier against delamination between composite layers.

To complete our study of the effect of AC-GC, Gr-GC, AC-GT, and Gr-GT fillers on the mechanical properties of their composites with GFRP, Fig. 8 presents the impact strength of all the composites, both with or without nano reinforcements, to assess their load-bearing capacity under sudden loading conditions. The impact strength increased by 14.1% and 21.5% for 0.25 phr AC-GC and 0.25 phr AC-GT but for 0.50 phr Gr-GC and 0.50 phr Gr-GT, it increased by 16.4% and 7.5% compared to that of GFRP. The impact strength increase with respect to the pristine E-glass fiber/epoxy is possibly due to the robust sp2 carbon bonds in rGO structure that imparted the reinforcing effect of rGO within the adhesive system. In comparison to 0.25 AC-GC and AC-GT system and 0.50 Gr-GC and Gr-GT, the impact strength for higher than the optimal loading reduced which can be attributed to the agglomerating effect of rGO at higher concentration, which negatively affects impact strength42. Aradhana et al.36 investigated the impact strength of both epoxy/GO and epoxy/rGO systems. They observed a significant increase as the notch depth decreased from 2.54 to 0.5 mm across all adhesive systems, indicating a clear transition from brittle to ductile behavior due to the reduction in the stress concentration area. Their study demonstrates the potential of epoxy/rGO composites for improved impact strength. Mi and colleagues synthesized hybrids of halloysite nanotubes-reduced graphene oxide (HRGO) by concurrently reducing and hybridizing graphene oxide with halloysite nanotubes, which were then incorporated into epoxy resin. The inclusion of 0.2 wt% HRGO resulted in a remarkable 104.8% increase in impact strength43. Adak and co-workers introduced thermally reduced graphene oxide (TRGO) as a reinforcing filler in epoxy resin to examine its impact on the mechanical properties of carbon fiber (CF)/epoxy composites. The impact strength surged by 93% with a TRGO loading of 0.2 wt% in the CF/epoxy composites compared to CF-reinforced epoxy alone44. It was observed that the wrinkled structure of synthesized TRGO may be helpful in interlocking with the epoxy resin and CF.

Studies have shown that incorporating reduced graphene oxide into GFRP composites significantly improves their tensile and flexural strength. Table S1 shows the selected literature representing the potential of graphene in GFRP composites. For instance, Kiratli et al. investigated the effects of adding graphene nanoplatelets to an epoxy matrix at concentrations of 0.25 wt%, 0.5 wt%, and 1 wt%. They found that the flexural strengths increased by 4.32%, 12.88%, and 7.03%, respectively. Table S1 also depicts our recent work which shows the potential for coal-derived graphene oxide in GFRP composites. Table 1 provides the summary of the mechanical properties achieved at the optimized concentration of nanofiller in the GFRP composites.

Comparison of the mechanical properties of Coal-derived GO and rGO

As evident in table S1, AC-GO and Gr-GO showed their best mechanical behavior at 0.125 phr and 0.25 phr loading in GFRPs respectively. This behavior is attributed to AC-GO’s smaller particle size distribution which results in a larger surface area-to-volume ratio compared to Gr-GO shown in DLS studies by Garg et al.22. This enhances the mechanical properties of AC-GO based composites at lower nanofiller concentrations in GFRP systems, compared to Gr-GO based composites. To test, whether the particle size had a significant role in case of rGOs, DLS studies were performed. Figure 9 shows the DLS studies for different synthesized rGOs.

From Fig. 9, it was observed that coal-derived rGOs had significantly higher particle size distribution as compared to AC-GO (0.17 μm as reported in21). These results were consistent with the20 where the Coal-rGO exhibited a bit larger particle size in the range of 200–600 nm in comparison to the Coal-GO synthesized in their study. This can be attributed to the restacking of highly agglomerated particles in an aqueous dispersion. Fu et al.45 depicted that particle size has a more pronounced effect on tensile strength. Despite the different synthesis techniques, AC-GC and AC-GT had almost similar particle size distribution, therefore, the increase in tensile strength was also quite similar, i.e., 25% for AC-GT-based composites, and 23.4% for AC-GC-based composites. These values are quite higher than those observed for AC-GO in our previous study21. The tensile strength increased by 18.3% in the case of AC-GO-reinforced GFRPs. This happens due to proper dispersion of hydrophobic nanofiller, i.e., AC-GC and AC-GT in the hydrophobic epoxy matrix. The nature of the nanofiller has a significant impact on the mechanical properties of composites. Cazan et al.46 in their review presented many studies showed that improvements in the mechanical strength and modulus of TiO2-filled polymeric nanocomposites compared to the pristine-base matrix. The mechanical properties of the TiO2 nanocomposites depend significantly on their internal structure. The poor compatibility of hydrophilic TiO2 nanoparticles with a hydrophobic polymer matrix may lead to particle aggregates and/or agglomerates. The aggregates create defect sites in the nanocomposites, and the improvement in mechanical properties is not observed. However, they stated that as the particle size decreases significantly into 1D or 2D nanoparticles, i.e., nanorods, nanotubes or nanoribbons, particles with a high aspect ratio, more uniform dispersion can be achieved. Therefore, AC-GO being hydrophilic nanofiller showed better dispersion due to their reduced particle size in comparison to rGOs and also owing to the functional groups spread over the surface or the edges without disrupting the internal structure. In the case of rGOs, similar surface energies of the hydrophobic filler and matrix minimize interfacial tension, facilitating better dispersion47 leading to improvement in mechanical aspects of GFRPs. Another vital aspect to be considered is the interfacial bonding between rGO nanofiller and the epoxy matrix which plays an important role in the overall improvement in mechanical properties. Despite the reduction process, rGO often retains a small fraction of oxygen-containing groups (e.g., hydroxyl and carboxyl groups) on its surface. These groups can form covalent bonds or hydrogen bonds with the epoxy matrix during curing, enhancing interfacial adhesion. The rough, wrinkled surface of rGO enhances mechanical interlocking with the epoxy matrix, strengthening the interface and enabling efficient load transfer. Strong interfacial bonding ensures effective stress transfer from the matrix to the rGO, which is vital for improving the mechanical properties, such as tensile strength, flexural properties, and impact strength48. Additionally, it minimizes the formation of voids or defects at the interface, which could otherwise act as stress concentrators.

FESEM images of fractured surfaces of FRP composites and toughening mechanism

Fractured surfaces of tensile samples were analyzed using FESEM to investigate dispersion and compatibility, two key factors influencing the interaction between glass fiber and the epoxy polymer matrix49. Figure S4 uncovered prominent wide gaps between fibers and the epoxy matrix, suggesting insufficient interfacial adhesion. The lack of bonding between the fiber and the matrix leads to significant fiber pull-out under stress, resulting in decreased fracture resistance and easy detachment of fibers from the matrix. This detachment creates voids, leading to straightforward material fracture. Weak interfacial bonding causes the material to deform under relatively low loads. In simpler terms, GFRPs without AC-GC, Gr-GC, AC-GT, and Gr-GT fillers exhibit low strength50. Additionally, the surface of the control GFRP sample facilitated crack propagation, allowing failure to spread extensively without encountering any barriers. The rGOs derived from coal or graphite in the multiscale composite samples serve as obstacles that hinder crack propagation and the linear expansion of fracture surfaces. As deformation initiates and a crack advances within the composite material, it encounters multiple nanofillers and interfaces between fibers and the matrix, which collectively impede the progression of the crack. The resistance exerted by the fillers forces the crack to alter its trajectory, effectively prolonging its path. This deflection in the crack growth path owes to the enhancing mechanical properties of the composites. Alternatively, the crack’s advancement through the material may also result in the fracturing or splintering of the fillers themselves. This process requires a large amount of energy51,52. Another toughening mechanism involves rGO pullout, as illustrated in Fig. 10 (a, c). It’s worth noting that tensile stress is transferred to the rGOs, causing them to stretch in the direction of tension. Ultimately, the improvement in the mechanical properties of the multiscale composite samples with 0.25 AC-GC, 0.25 AC-GT, and 0.50 Gr-GC, 0.50 Gr-GT content can be credited to the uniform dispersion of graphene, as evidenced by the consistent fracture surface (see Fig. 10 (a, c) and Fig. 11 (a, c))53. Conversely, the formation of cracks in the agglomeration areas of rGOs at concentrations higher (0.75 phr) than the optimal loading exerts detrimental effects on the mechanical properties attributable to particle aggregation and poor bonding illustrated in Fig. 10 (b, d) and Fig. 11 (b, d)54.

Noting that clear identification of AC-GC, AC-GT, Gr-GC, and Gr-GT in the polymer matrix from the FESEM micrograph is quite difficult, therefore, EDX analysis has been done to confirm the presence of the nanofillers. The EDX spectra (see Figure S5 and Figure S6) confirm the presence of C, O, N (from AC- rGO and Gr- rGO) as well as aluminosilicates (from E-Glass fiber). The presence of N has also been observed in coal-based GFRPs which might be due to its inherent presence in the coal microstructure from which rGO is synthesized.

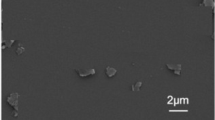

Figure 12 presents the SEM images of rGO synthesized from coal and graphite. Regardless of the synthesis technique, all rGO samples exhibit a flaky, layered morphology with distinctly rough surfaces. Although the wrinkled morphology is not resolved at the presented SEM scale, its mechanical effect remains plausible based on the material’s known structural characteristics and previously reported findings. These wrinkles prevent restacking, promote better dispersion, and provide mechanical interlocking within the matrix, contributing to stress transfer efficiency55,56.

Interaction Mechanism of rGO–Epoxy Interface Even without deliberate surface functionalization, rGO can form a robust interface with an epoxy matrix through non-covalent bonding and physical entanglement. In particular, rGO typically retains some residual oxygen functional groups (e.g. hydroxyls, carboxyl or epoxides) from incomplete reduction, which are capable of hydrogen bonding with the epoxy network (for example, with hydroxyls formed during cure or polar amine/epoxy groups)57. Such hydrogen bonding contributes significantly to interfacial adhesion, as evidenced by studies showing that H-bond interactions greatly strengthen epoxy/graphene oxide interfaces. Additionally, the aromatic graphitic domains of rGO can engage in π–π stacking with the aromatic rings of epoxy resin (e.g. the phenylene groups in DGEBA-based epoxy)58. These π–π interactions create attractive forces at the filler–matrix interface, which can act as “sacrificial bonds” that dissipate energy and improve stress transfer under load. Moreover, the two-dimensional sheet geometry of rGO (often wrinkled or crumpled in morphology) leads to mechanical interlocking within the cured polymer network. The epoxy matrix can conform around the graphene sheets, and the large aspect ratio of rGO impedes pull-out, thereby enhancing frictional stress transfer37, . Together, these mechanisms – hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking, and mechanical interlocking – synergistically improve the interfacial bonding between unfunctionalized rGO and epoxy, resulting in more effective load transfer in the composite.

Conclusions

In this study, a comprehensive experimental study to assess the impact of AC-GC and AC-GT (synthesized from AC-GO via chemical and thermal reduction methods) and Gr-GC and Gr-GT (synthesized from graphite via chemical and thermal reduction methods) nanofillers on the mechanical properties of GFRP composites, including tensile and flexural properties, as well as impact strength has been conducted. These results were compared with a control composite comprising E-glass fiber and epoxy resin (EGFP) without any nanofiller. The key findings are as follows:

-

An optimal threshold concentration of the AC-GC and AC-GT filler (0.25 phr) and of Gr-GC and Gr-GT filler (0.50 phr) was identified, beyond which the mechanical properties significantly decrease due to particle aggregation, as indicated by SEM. The aggregation results in fewer available bonding sites and a reduced aspect ratio, ultimately leading to lower reinforcement efficiency. AC-GC and AC-GT exhibited optimal loading rate at a lower concentration of 0.25 phr in comparison to Gr- rGO based nanofillers. This is attributed to the smaller particle size distribution of AC- rGO, leading to a larger surface area-to-volume ratio compared to larger particles of Gr- rGO, which contributes to achieving better mechanical properties of AC-rGO based composites at lower concentrations of nanofiller loading in GFRP systems as compared to Gr- rGO.

-

SEM studies revealed that rGOs derived from coal or graphite in the multiscale composite samples serve as obstacles that hinder crack propagation and the linear expansion of fracture surfaces. The AC- rGO, demonstrating its optimal mechanical behavior at 0.25 phr, confirms our hypothesis. The hydrophobic nature of rGO, similar to the matrix, ensures proper dispersion, unlike GO which leads to significant improvement in mechanical properties. This results in enhanced mechanical properties.

-

The effective enhancement in mechanical properties of Coal-rGO-based composites opens up a new class of materials critical for various industrial applications in aerospace, marine, sports equipment, and defense sectors.

Data availability

Data will be made available on reasonable request from corresponding author.

References

Wang, Q. et al. An embedded non-intrusive graphene/epoxy broadband nanocomposite sensor co-cured with GFRP for in situ structural health monitoring. Compos. Sci. Technol. 236, 109995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2023.109995 (2023).

Jamshaid, F. et al. Tactical tuning of mechanical and thermo-mechanical properties of glass fiber/epoxy multi-scale composites by incorporating N-(2-aminoethyl)-3-aminopropyl trimethoxysilane functionalized carbon nanotubes. Iran. Polym. J. 29, 875–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13726-020-00848-y (2020).

Hu, K., Kulkarni, D. D., Choi, I. & Tsukruk, V. V. Graphene-polymer nanocomposites for structural and functional applications. Prog Polym. Sci. 39, 1934–1972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2014.03.001 (2014).

Mirabedini, A. et al. Evolving strategies for producing multiscale graphene-enhanced fiber‐reinforced polymer composites for smart structural applications. Adv. Sci. 7, 1903501. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201903501 (2020).

Jamshaid, F., Khan, R. U. & Islam, A. Performance improvement of glass fiber/epoxy composites upon integrating with N-(2-aminoethyl)-3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane functionalized graphene oxide. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 31, 3810–3822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10904-021-02015-z (2021).

Zhao, J. et al. Simultaneously tuning interfacial and interlaminar properties of glass fiber fabric/epoxy laminated composites via modifying fibers with graphene oxide. Compos. Sci. Technol. 235, 109970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2023.109970 (2023).

De, S. et al. Elevated-temperature mechanical performance of GFRP composite with functionalized hybrid nanofiller. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 139, e53223. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.53223 (2022).

Sasidharan, S. & Anand, A. Epoxy-based hybrid structural composites with nanofillers: A review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 12617–12631. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.0c01711 (2020).

Mishra, B. P., Mishra, D. & Panda, P. An experimental investigation of the effects of reinforcement of graphene fillers on mechanical properties of bi-directional glass/epoxy composite. Mater. Today Proc. 33, 5429–5441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.03.154 (2020).

Shabberhussain, S. & Velmurugan, R. Effect of graphene nanoplatelets on mechanical performance of GFRP composites. Mater. Sci. Forum Trans. Tech. Publ. https://doi.org/10.4028/p-dm021j (2022).

Çakır, M. V., Erkliğ, A. & Ahmed, B. F. Graphene nanoparticle effect on flexural and shear behaviors of adhesively bonded single lap joints of GFRP composites. J. Brazilian Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 43, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40430-021-02920-x (2021).

Quaresimin, M., Schulte, K., Zappalorto, M. & Chandrasekaran, S. Toughening mechanisms in polymer nanocomposites: From experiments to modelling. Compos. Sci. Technol. 123, 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2015.11.027 (2016).

Atif, R., Shyha, I. & Inam, F. Mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties of graphene-epoxy nanocomposites-A review. Polym. (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym8080281 (2016).

Zaaba, N. I. et al. Synthesis of graphene oxide using modified hummers method: solvent influence. Procedia Eng. 184, 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.04.118 (2017).

Shams, S. S. et al. Synthesis of graphene from biomass: A green chemistry approach. Mater. Lett. 161, 476–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2015.09.022 (2015).

Marcano, D. C. et al. Correction to improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS Nano, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.8b00128

Al-Mufti, S. M. S., Almontasser, A. & Rizvi, S. J. A. Influence of temperature variations on the dielectric parameters of thermally reduced graphene oxide. Mater. Today Proc. 57, 1713–1718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.12.344 (2022).

Al-Mufti, S., Almontasser, A. & Rizvi, S. J. A. Single and double thermal reduction processes for synthesis reduced graphene oxide assisted by a muffle furnace: A facile robust synthesis and rapid approach to enhance electrical conductivity. AIP Adv. 12, 125306. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0128803 (2022).

Alam, S. N., Sharma, N. & Kumar, L. Synthesis of graphene oxide (GO) by modified hummers method and its thermal reduction to obtain reduced graphene oxide (rGO)*. Graphene 06, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.4236/graphene.2017.61001 (2017).

Lee, S. Y. & Mahajan, R. L. A facile method for coal to graphene oxide and its application to a biosensor. Carbon 181, 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2021.05.007 (2021).

Garg, A. et al. Simplified One-Pot synthesis of graphene oxide from different coals and its potential application in enhancing the mechanical performance of GFRP nanocomposites. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6 (15), 14594–14608. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.3c03197 (2023).

Garg, A., Basu, S., Mehta, R. & Mahajan, R. L. Enhancing the mechanical performance of E-glass fiber epoxy composites using coal‐derived graphene oxide. Polym. Compos. 45 (3), 2444–2461. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.27931 (2023).

Ahmad, H., Fan, M. & Hui, D. Graphene oxide incorporated functional materials: A review. Compos. Part. B Eng. 145, 270–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.02.006 (2018).

Mitra, M. et al. Reduced graphene oxide-polyaniline composites—synthesis, characterization and optimization for thermoelectric applications. RSC Adv. 5, 31039–31048. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA01794G (2015).

Ejaz, H. et al. An experimental and simulation study of RGO effects on mechanical behaviour of structural adhesive and lap shear joints strength. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 126, 103480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2023.103480 (2023).

Khabaz-Aghdam, A. et al. Effect of reduced graphene oxide on mechanical behavior of an epoxy adhesive in glassy and rubbery States. J. Compos. Mater. 55, 3839–3848. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219983211031659 (2021).

Marami, G. et al. Improving the mechanical behavior of the adhesively bonded joints using RGO additive. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 70, 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2016.07.014 (2016).

Dubey, U. & K P Low-combustible, high-strength, and thermally stable bio-blended epoxy-based bio-nanocomposite using reduced graphene oxide as a strengthening agent. J. Reinf Plast. Compos. https://doi.org/10.1177/07316844241279013 (2024).

Adekomaya, O., Adediran, A. A. & Adama, K. Characterization and morphological properties of glass fiber reinforced epoxy composites fabricated under varying degrees of hand lay-up techniques. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 22, 110. https://doi.org/10.4314/jasem.v22i1.20 (2018).

Alhumade, H., Rezk, H., Nassef, A. M. & Al-Dhaifallah, M. Fuzzy logic Based-Modeling and parameter optimization for improving the corrosion protection of stainless steel 304 by Epoxy-Graphene composite. IEEE Access. 7, 100899–100909. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2930902 (2019).

Zheng, Y. et al. Raman spectroscopy and correlative-Raman technology excel as an optimal stage for carbon‐based electrode materials in electrochemical energy storage. J. Raman Spectrosc. 52, 2119–2130. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.6178 (2021).

Siddique, Z. B., Basu, S. & Basak, P. Development of graphene oxide dispersed natural ester based insulating oil for Transformers. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 28, 1326–1333. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2021.009445 (2021).

Oliveira, A. E. F., Braga, G. B., Tarley, C. R. T. & Pereira, A. C. Thermally reduced graphene oxide: synthesis, studies and characterization. J. Mater. Sci. 53, 12005–12015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-018-2473-3 (2018).

Deng, J. et al. The surface modification effect on the interfacial properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy: A molecular dynamics study. Nanotechnol Rev. 11, 1143–1157. https://doi.org/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0068 (2022).

Kanny, K. & Mohan, T. P. Resin infusion analysis of nanoclay filled glass fiber laminates. Compos. Part. B Eng. 58, 328–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.10.025 (2014).

Aradhana, R., Mohanty, S. & Nayak, S. K. Comparison of mechanical, electrical and thermal properties in graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide filled epoxy nanocomposite adhesives. Polym. (Guildf). 141, 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2018.03.005 (2018).

Olowojoba, G. B. et al. In situ thermally reduced graphene oxide/epoxy composites: thermal and mechanical properties. Appl. Nanosci. 6, 1015–1022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-016-0518-y (2016).

Tschoppe, K., Beckert, F., Beckert, M. & Mülhaupt, R. Thermally reduced graphite oxide and mechanochemically functionalized graphene as functional fillers for epoxy nanocomposites. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 300, 140–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/mame.201400245 (2015).

Chhetri, S. et al. Functionalized reduced graphene oxide/epoxy composites with enhanced mechanical properties and thermal stability. Polym. Test. 63, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymertesting.2017.08.005 (2017).

Martin-Gallego, M. et al. Comparison of filler percolation and mechanical properties in graphene and carbon nanotubes filled epoxy nanocomposites. Eur. Polym. J. 49, 1347–1353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2013.02.033 (2013).

Liu, P., Yao, Z. & Zhou, J. Investigation of thermal properties and mechanical properties of reduced graphene oxide/polyimide resin composites. Polym. Compos. 38, 2321–2331. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.23815 (2017).

Sharmila, T. K. B. et al. Mechanical, thermal and dielectric properties of hybrid composites of epoxy and reduced graphene oxide/iron oxide. Mater. Des. 90, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2015.10.055 (2016).

Mi, X. et al. Fabrication of Halloysite nanotubes/reduced graphene oxide hybrids for epoxy composites with improved thermal and mechanical properties. Polym. Test. 76, 473–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymertesting.2019.04.007 (2019).

Adak, N. C. et al. Effect of thermally reduced graphene oxide on mechanical properties of woven carbon fiber/epoxy composite. Crystals 8, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst8030111 (2018).

Fu, S. Y., Feng, X. Q., Lauke, B. & Mai, Y. W. Effects of particle size, particle/matrix interface adhesion and particle loading on mechanical properties of particulate-polymer composites. Compos. Part. B Eng. 39, 933–961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2008.01.002 (2008).

Cazan, C., Enesca, A. & Andronic, L. Synergic effect of TiO2 filler on the mechanical properties of polymer nanocomposites. Polym. (Basel). 13, 2017. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13122017 (2021).

Rong, M. Z., Zhang, M. Q. & Ruan, W. H. Surface modification of nanoscale fillers for improving properties of polymer nanocomposites: a review. Mater. Sci. Technol. 22, 787–796. https://doi.org/10.1179/174328406X101247 (2006).

Jamshaid, F., Khan, R. U. & Islam, A. Performance tuning of glass fiber/epoxy composites through interfacial modification upon integrating with dendrimer functionalized graphene oxide. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 138, 50876. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.50876 (2021).

Bhanuprakash, L., Ali, A., Mokkoth, R. & Varghese, S. Mode I and mode II interlaminar fracture behavior of E-glass fiber reinforced epoxy composites modified with reduced exfoliated graphite oxide. Polym. Compos. 39, E2506–E2518. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.24809 (2018).

Prusty, R. K., Ghosh, S. K., Rathore, D. K. & Ray, B. C. Reinforcement effect of graphene oxide in glass fibre/epoxy composites at in-situ elevated temperature environments: an emphasis on graphene oxide content. Compos. Part. Appl. Sci. Manuf. 95, 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2017.01.001 (2017).

Shakuntala, O., Raghavendra, G. & Samir Kumar, A. Effect of filler loading on mechanical and tribological properties of wood Apple shell reinforced epoxy composite. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/538651 (2014).

Rafiee, M. A. et al. Fracture and fatigue in graphene nanocomposites. Small 6, 179–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.200901480 (2010).

Eqra, R., Janghorban, K. & Daneshmanesh, H. Mechanical properties and toughening mechanisms of epoxy/graphene nanocomposites. J. Polym. Eng. 35, 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1515/polyeng-2014-0134 (2015).

Chandrasekaran, S. et al. Fracture toughness and failure mechanism of graphene based epoxy composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 97, 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2014.03.014 (2014).

Stankovich, S. et al. Graphene-based composite materials. Nature 442, 282–286. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04969 (2006).

Kim, H., Abdala, A. A. & Macosko, C. W. Graphene/polymer nanocomposites. Macromolecules 43, 6515–6530. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma100572e (2010).

Shrestha, A. et al. Molecular Understanding of adhesion of epoxy resin to graphene and graphene oxide surfaces in terms of orbital interactions. Langmuir 39, 5514–5526. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.3c00262 (2023).

Han, X. et al. Effect of π–π stacking interfacial interaction on the properties of graphene/poly (styrene-b-isoprene-b-styrene) composites. Nanomaterials 11, 2158. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11092158 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to TIET-VT, Center of Excellence in Emerging Materials (CEEMS), Thapar Institute of Engineering & Technology, Patiala, India, CIPET, Amritsar, SAI Labs at TIET, DPMS at TIET for the mechanical testing facility and characterizations. The study was supported by TIET-VT, CEEMS via the project code, 8026.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: A.G., S.B., R.L.M., R.M. Experimentation: A.G. Analysis/interpretation of data: A.G. Drafting the manuscript: A.G. Critical reviewing of manuscript: S.B., R.L.M., R.M. Approval of the final manuscript: A.G., S.B., R.L.M., R.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Garg, A., Basu, S., Mahajan, R.L. et al. Effect of rGO synthesized from different precursors on the enhancement in mechanical properties of GFRPs. Sci Rep 15, 29108 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04488-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04488-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Role of rGO in improving the mechanical and thermal performance of PANI/graphene nanocomposites

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Nickel and graphene oxide enhanced bismuth oxide for humidity sensing capabilities

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2025)