Abstract

The conversion of gamma particles into optical photons in state-of-the-art scintillator materials is limited to maximum 10 emitted photons per MeV of energy deposited per picosecond, when the material is excited at room-temperature. Breaking this limit has both fundamental and applied importance, and motivates the search for fast and efficient optical emitters at excitation densities relevant for particle detection, up to 1020 electron–hole pairs (eh) per cm3. In this work, we address this challenge by probing the optical response of a promising nanomaterial, CdSe/CdS core/crown nanoplatelets (NPLs), in the shape of drop cast films using intense femtosecond laser pulses. The study finds that the NPL films exhibit a bright optical response at low to medium excitation densities but suffer from high levels of nonlinear quenching, dominated by exciton-exciton annihilation (EEA), at densities exceeding 1017 eh/cm3. The experimental data and theoretical calculations suggest that EEA is enhanced in the drop cast film by the close packing of NPLs which allows excitons to migrate between NPLs in the film. Despite this, light yield estimations based on a simulated distribution of excitation densities predict values upwards of 2000 ph/MeV, while showing ample room for improvement and the future potential of surpassing the 10 ph/MeV/ps benchmark.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Excitons are interesting quasiparticles driving a wide range of luminescence phenomena, ranging from scintillation, i.e. light emission upon the passage of ionizing radiation, to bright and ultrafast luminescence in 2D direct bandgap semiconductor nanoplatelets (NPLs). CdSe NPLs are of particular interest as they exhibit an enhanced excitonic binding energy1,2,3,4 leading to an extremely stable excitonic population at high excitation densities5,6. This gives rise to room-temperature stable biexcitons with a unique sub-ns decay component7. These features, combined with reduced Auger-driven quenching, make them fast and efficient emitters8. Possible applications of this material are vast and varied in nature ranging from using it as a laser gain material7,9, a photocatalyst for hydrogen production through water splitting10, and even as a time-tagger for ionizing radiation detection11. The latter application is motivated by a need for improved time resolution when measuring two 511 keV gamma photons in coincidence in Time-Of-Flight Positron Emission Tomography (TOF-PET)12. An overview of the state-of-the art optical response of scintillator materials relevant for the TOF-PET technique is displayed in Fig. 1a which points to an optical response region with ultrafast decay times (<1 ns) and high light yields (> 10000 photons/MeV) which remains to this day inaccessible. A material with such an optical response, i.e. > 10 ph/MeV/ps, would allow for measuring the coincidence of two 511 keV gamma photons with a time resolution of 10 ps opening up a new avenue for the TOF-PET imaging technique13. Nanomaterials such as CdSe NPLs could be the gateway to this optical region, but implementing them into 511 keV gamma spectroscopy is complicated as the recoil electron path length is much longer than the NPL size, a concept which is visualized in the inset of Fig. 1a. In this sense, the nanoscale geometry that gives rise to the desirable optical properties are simultaneously imposing a severe limitation on measurements of macroscopic parameters such as light yield.

(a) Optical response map for state-of-the-art scintillators in terms of their light yield, decay time, and time resolution measured in a coincidence setup using 511 keV gamma photons. The shaded area shows the scintillation performance open to exploration in this study. (b) z-scan luminescence technique proposed for the optical characterization of promising nanoscintillators at high excitation densities. (c) z-scan luminescence signatures expected for materials where Auger-Meitner recombination (3rd order) or exciton-exciton annihilation (2nd order) are the dominant processes responsible for nonlinear quenching. (d) A sketch of the relevant physical processes that can occur upon optical excitation of the materials under study either in the bulk, or within one NPL.

In this study, we address this issue by introducing a method for evaluating the performance of a nanomaterial under conditions that emulate interaction with ionizing radiation utilizing focused ultrashort pulses of optical photons in the technique known as inter-band z-scan luminescence. This technique is realized by measuring a fraction of the number of emitted photons while optically stimulating a material at different excitation densities and keeping the energy of the optical pulses constant, as sketched in Fig. 1b. This allows for precise control of the electron-hole pair generation process and provides a pathway towards understanding the physical nature of luminescence and quenching mechanisms in a wide variety of scintillators14,15,16,17,18.

Two typical z-scan luminescence traces of materials with a strong Coulomb interaction, where the free carriers bond into excitonic species, are shown in Fig. 1c. As the excitation density increases, the light yield begins to drop in a process called nonlinear quenching (NLQ) which results from the excited species interacting with each other as sketched in Fig. 1d. During thermalization, the excited species are free carriers and can undergo Auger-Meitner recombination in which an electron-hole pair recombines by transferring energy to a third carrier. Since it is a three-particle process, it will have a third order dependence in excitation density15,16. After thermalization, the free carriers form excitons and NLQ mainly occurs as exciton-exciton annihilation (EEA), in which an exciton decays non-radiatively by transferring energy to a nearby exciton, which then ionizes in an Auger-like, two-(quasi)particle process19. From z-scan luminescence traces, it is possible to distinguish materials where NLQ is dominated by either Auger-Meitner recombination or EEA, illustrated in Fig. 1c and called 3rd and 2nd order, respectively.

By applying a second-order quenching model to our experiments, we can analytically replicate NLQ measurements across five orders of magnitude of excitation density. This allows us to quantify the optical performance of materials at excitation densities occurring upon interaction with ionizing radiation. The light yield of a nanomaterial can then be estimated by calibrating the z-scan measurements to a well known scintillator and using a simulated distribution of excitation densities. The material chosen for this study is 4.5 monolayer (ML) CdSe/CdS core/crown NPLs and \(\hbox {Bi}_4\) \(\hbox {Ge}_3\) \(\hbox {O}_{12}\) (BGO) as the reference material. To replicate the possible integration of the NPLs in an ionizing radiation detection setup, we study the material as drop cast films. Our findings demonstrate that CdSe NPLs are powerful optical emitters with significant untapped potential. However, it seems that the close packing of NPLs in the drop cast film allows excitons to diffuse throughout the sample, effectively enhancing the EEA.

(a) A sketch of the optical setup from light source to sample where each optical component is labeled. The excitation wavelength can be switched from the fourth harmonic to the second harmonic by removing all the optical elements in the beige box. (b) Peak fluence measurements of the second and fourth harmonic at the sample position are presented along with fits on the form of Eqs. (1) and (2). The two y-axes to the right indicate the induced peak excitation densities in CdSe/CdS core/crown NPLs and BGO respectively calculated from Eq. (3).

Spatial distribution of excitation

At the heart of the z-scan method is the ability to vary the optical density of the excitation delivered to the sample while keeping total energy of the pulses constant. This is achieved using a translating lens with a travel direction parallel to the beam which moves the beam waist and changes the excitation density in the stationary sample plane. This is sketched in Fig. 2a. For a Gaussian beam, the peak fluence in the sample plane can be expressed as:

where \(w_{x,y}\) are the Gaussian widths of the beam, found by fitting to a Gaussian beam profile and \(E_p\) is the energy of the optical pulse. For a perfectly collimated beam with wavelength \(\lambda ,\) and defining \(z = 0\) to be the lens position which places the beam waist, \(w_0\), at the sample surface, the beam widths can be expressed as:

where M is the unitless beam quality factor. To account for the different bandgaps of the materials, the second and fourth harmonic of a Ti:sapphire fs-laser with photon energies of 3 and 6 eV are used for measurements on the NPLs and BGO, respectively. This keeps the photon energy in the same regime where \(E_g< h\nu < 2E_g\) for both materials which ensures comparability between their quenching kinetics. Measurements of the peak fluence for both the second and fourth harmonic are shown in Fig. 2b along with fits essentially on the form of Eqs. (1) and (2). Details on the beam characterization can be found in the Supporting Information Section I.

(a) TEM image of the CdSe/CdS core/crown NPLs used in this paper. (b) An image of the drop cast sample on a Si-substrate. (c) Height profile of the drop cast sample. (d) Absorption and PL measurements of the core-only and core/crown samples in solution. The values are normalized to the Heavy-Hole absorption peak.

Drop cast NPL films

The 4.5 monolayer (ML) CdSe/CdS core/crown NPLs studied in this paper were synthesized following literature protocols reported in detail elsewhere20,21. The synthesis followed a two-step procedure where the CdSe core NPLs were synthesized first and a CdS crown was added later. The size distribution of core-only NPLs were found from analyzing Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) images and estimated as \({20\pm 4}\,\hbox {nm} \times {5\pm 1}\,\hbox {nm}\). A TEM image of the core/crown NPLs used in this paper is shown in Fig. 3a.

The NPLs are studied as a drop cast film on a silicon substrate. In order to obtain the most homogeneous film, the evaporation process was slowed down by adding heptane to the solution just before the casting. The sample homogeneity was confirmed visually (see Fig. 3b) and by measuring a height profile which is presented in Fig. 3c. The sample height of around \({3}\,\upmu \hbox {m}\) ensures that measurements are made in the thick sample limit where all the energy of the optical pulses is absorbed in the film. A film thickness at least on the \(\upmu\text{m}\)-scale is also a requirement for TOF-PET applications22.

Spectrally resolved absorption and photoluminescence (PL) measurements of the core-only and core/crown samples in solution are shown in Fig. 3d. The core-only absorption spectrum shows two distinct absorption peaks at 509 and 480 nm owing to Heavy-Hole (HH) and Light-Hole (LH) exciton lines, respectively, which is consistent with previously published data1,2,9,21,23,24,25. After crowning, both the PL peak and the HH absorption peak are slightly redshifted by about 3 nm which is attributed to a changing dielectric environment for the excitons24. The core/crown absorption spectrum also exhibits a distinct absorption peak around 406 nm which is identified as the overlapping HH and LH exciton lines in 4.5 ML CdS NPLs2. The lack of any PL emission peak in the spectral range between 400–450 nm confirms that the sample is free from CdS NPLs26.

From the absorption spectra of the core-only and core/crown samples in solution, it is possible to estimate the volume fraction of CdSe to CdS in the NPLs by using the Maxwell-Garnet effective medium approach to calculate their absorption coefficients27. Using this method, the volume fractions of CdSe/Cds, \(f_{\text {CdSe}}/f_{\text {CdS}}\), were found to be 37%/63% respectively. From this, we calculate volume of the core/crown NPLs as \(V_{\text {NPL}} = 369\,\hbox {nm}^{3}\) which means that 1 exciton per NPL corresponds to an excitation density of \(\sim 3\times 10^{18}\hbox {cm}^{-3}\). We also use the volume fractions to calculate the linear absorption coefficient, \(\alpha\), of the NPLs in the drop cast films. This is used to convert the measured peak fluence at a given lens position to an induced excitation density in terms of electron-hole-pairs per volume in the NPLs. From this calculation, we estimate the linear absorption coefficient of the NPLs in the drop cast sample to be \(3.3\times 10^{5}\,\hbox {cm}^{-1}\) at 3 eV excitation. This value is supported by direct transmission measurements on thinner samples made from the same NPL synthesis drop cast on a transparent substrate. Details on the theoretical estimate for the absorption coefficient and the transmission measurements are presented in the Supporting Information Section II. For BGO, the linear absorption coefficient is known to be \(5.4\times 10^{5}\,\hbox {cm}^{-1}\) at 6 eV excitation28.

The initial peak excitation density can be expressed for each lens position as

where R is the reflection coefficient, measured to be 0.1 for the drop cast NPL film and set at 0.3 for BGO15. The peak excitation densities created in the NPLs and BGO are related to the peak fluence of the second and fourth harmonic, respectively, in Fig. 2b.

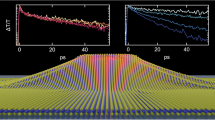

(a) The measured nonlinear luminescence efficiency of BGO and CdSe/CdS core/crown NPLs plotted against the peak excitation density. This data is referred to as a NLQ trace. Fits to the data on the form of Eq. (7) with a constant background added are also shown. The insert shows an average of digitized PMT pulses measured at an excitation density of \(5\times 10^{16}\,\hbox {cm}^{-3}\) where the signal from BGO has been scaled by a factor of 6. (b) The probability density function of excitation densities found by simulating 662 keV \(\gamma\)-ray deposition in Yttrium Aluminium Garnet29 is shown alongside the integrants of Eq. (11) for BGO and the NPL film. The calculated effective nonlinear luminescence efficiencies and the predicted light yields are also presented.

Second order quenching model

Both materials studied in this paper have excitonic luminescence and therefore we describe the NLQ dynamics using a second order model. The differential equation for the density of the excitonic population, n, can be written as:

where \(\tau ^{-1} = R_1+Q_1\) is the sum of the linear rate constants encompassing both radiative and non-radiative processes, the rates of which are given by \(R_1\) and \(Q_1\), respectively. We neglect a generation term and simply assume an initial population of excitons equal to the excitation density generated by the laser pulse which is a Gaussian distribution with a peak excitation density given by Eq. (3). Second order quenching is represented through the bi-molecular coefficient \(k_2\) which can be constant or time-dependent depending on the system under study.

The decay kinetics of CdSe NPLs and other 2D semiconductors have previously been studied in solution using a second order model with an EEA coefficient, \(k_2\), constant in time9,30,31,32. This model is theoretically valid for systems where excitons can undergo fast 3D diffusion33 or for isolated NPLs in solution where diffusion is disregarded and EEA can only occur between excitons within the same NPL34. Alternatively, when exciting NPLs in drop cast films, the excitons are expected to migrate through non-radiative energy transfer in self-assembled stacks of NPLs. Both the self assembly into needle-like stacks and the ability of the excitons to migrate through these have been thoroughly documented35,36,37,38,39. We therefore introduce a model to describe the exciton kinetics in NPL films which takes diffusion of excitons in 1D into account. Specifically, excitons are considered able to move randomly between NPLs in the film and quench via EEA if they occupy the same NPL. This gives rise to a time-dependent second order quenching term on the form of

where \(V_{\text {NPL}}\) is the volume of each NPL, a is the average distance between NPLs in the stack, and D is the 1D diffusion coefficient. This model is based on theoretical work by Engel et al.33 and a full derivation of Eq. (5) can be found in the Supporting Information Section V.

For self-activated scintillators such as BGO, second order quenching is usually modeled through Förster resonant energy transfer between immobile dipoles, which is analytically described with a second order quenching coefficient on the form of

with \(R_{dd}\) being the Förster transfer radius40. This model has successfully described the luminescence kinetics of multiple self-activated scintillators such as BGO14,15,18,40. Since \(k_{2,\text { BGO}}\) and \(k_{2,\text { NPLs}}\) are functionally identical in their time-dependence, they will in the following analysis collectively be written as \(k_2 = \kappa _2t^{-1/2}\), while a constant EEA coefficient will be written as \(k_2 =Q_2\). Both models will be applied to both materials.

The luminescence efficiency, \(\eta\), is defined as the ratio of emitted photons to number of electron-hole-pairs created. The number of emitted photons are found by solving the differential equation for excitons for each initial population and integrating over space and time,

where \(T = t/\tau\),

where erf is the error-function and \(\text {Li}_2\) is the dilogarithmic function defined in the supporting information Eq. \((\text {S}46)\). Note that the luminescence efficiency can be split in to a constant linear part defined as \(\eta _{\text {lin}} = \frac{R_1}{R_1+Q_1}\), and a nonlinear part, \(\eta _{\text {NLQ}} = \eta /\eta _{\text {lin}}\) which depends on the initial concentration of excitons. The linear luminescence efficiency is an identical concept to the PL quantum efficiency (PLQE), which is a benchmark parameter for PL active materials. Details on the derivation of Eq. (7) can be found in the Supporting Information Section III.

Results

Data from z-scan luminescence experiments are shown for both the drop cast CdSe/CdS core/crown NPL film and the BGO crystal in Fig. 4a. The intensity of the PL signal upon above bandgap excitation is plotted as function of the peak excitation density and we will refer to this data as a NLQ trace. Luminescence efficiency fits on the form of Eq. (7) with an added constant background have been applied to the NLQ traces. It turns out that both model expressions from Eq. (9) fit the data very well (see Supporting Information Section IV) and only the model with a time-dependent \(k_2\) is plotted in Fig. 4a.

To ensure comparability between the NLQ traces in Fig. 4a, the position of the PMT was kept fixed and the sample faces were placed in exactly the same position. During both z-scans, the average optical pulse energy was set at 20 nJ and photon energies set at 3 eV and 6 eV for NPLs and BGO respectively. The PL signal at each excitation density has been normalized to the value of the linear luminescence efficiency.

The shape of the NLQ traces for both BGO and the NPLs is consistent with a quenching mechanism of second order. For BGO, this agrees with previous studies15,16. The NPLs, even though they are semiconductors, do not behave as their bulk counterparts under z-scan measurements. This is attributed to the fact that the emitting species are not free carriers but excitons due to their enhanced binding energy in the NPL geometry41, and it is consistent with previous studies of other quantum confined semiconductor materials42. The striking similarity between the NLQ traces of two very different materials, one is a dense crystal and one is a drop cast film of NPLs, is attributed to their common excitonic emission processes with fast thermalization times. It is also clear that the NPL film suffers from significantly more NLQ than BGO. In fact, at peak excitation densities as low as \(5\times 10^{16}\,\hbox {cm}^{-3}\) we already observe significant NLQ, \(\eta _{\text {NLQ}}\approx 0.9\), in the NPL film. As this excitation density corresponds to a maximum of 0.02 excitons per NPL, there is clear evidence for diffusion of excitons between NPLs within the film. To obtain a trustworthy estimate for the relative linear luminescence efficiencies of the NPL film to BGO, we measure the PL count rate for both materials at low excitation density with a PMT operating in single photon counting mode. We determine the relative linear luminescence efficiency of the NPL films compared to BGO as \(\eta _{\text {lin,NPLs}}/\eta _{\text {lin,BGO}} = 1.28\).

From the NLQ traces of BGO and the NPL film, we are able to estimate their relative light yield under conditions typically occurring upon ionizing radiation excitation. We do this by assuming a distribution of excitation densities, f(n), simulated for 662 keV \(\gamma\)-ray deposition in undoped Yttrium Aluminium Garnet (YAG) published in29 and reprinted in Fig. 4b. The choice of excitation density distribution will be discussed further in the discussion section. The predicted light yield of the two materials, LY, can be estimated by integrating the probability density function of this distribution weighted by the luminescence efficiency extracted from fits to the NLQ traces. The nonlinear component of luminescence efficiency found in Eq. (7) can be converted to depend on the average excitation density rather than the peak excitation density through the transformation17

Using transformed luminescence efficiencies, we can define an effective nonlinear luminescence efficiency at the given excitation density distribution

from which, the expected LY of the NPL film can be estimated

where \(\hbox {LY}_\text {BGO}\) is reported by the manufacturer as 8500 photons/MeV at 622 keV gamma ray excitation43. The integrants of Eq. (11) are shown in Fig. 4b alongside the calculated effective nonlinear luminescence efficiencies. Inserting the relative linear- and effective nonlinear luminescence efficiencies in Eq. (12), yields an estimate for the LY of CdSe/CdS core/crown NPL films of \(\sim 2000\,\)photons/MeV.

(a) The fitted luminescence efficiency for the NPL films transformed to depend on average excitation density is shown in green. The dotted line indicates the predicted luminescence efficiency for the NPLs in solution as a function of average excitation density. The average number of excitons per NPL is calculated by multiplying the average excitation density with the NPL volume, \(V_{\text {NPL}}\). (b) Fits to the observed NLQ traces for BGO and CdSe/CdS core/crown NPLs using the second order quenching model Eq. (7) with a time dependent \(k_2\) without adding a constant background. The normalized background level was found to be \(0.145\pm 0.001\) and \(0.022\pm 0.001\) for BGO and NPLs respectively. To highlight the functional dependence of Eq. (7) on the parameter \(\sqrt{\pi \tau }\kappa _2\) we have also included plots corresponding to the values: \(4\times 10^{-20}\), \(4\times 10^{-18}\), and \(4\times 10^{-16}\,\hbox {cm}^{3}\).

Discussion

Second order model

Since we are only examining time-integrated PL signals, and both models introduced in Eq. (9) fit the data, we are not really able to confirm the presence of excitonic diffusion in the NPL film based on the fits alone. However, as mentioned in the results section, evidence of diffusion can be found when looking at NLQ traces as a function of the average number of excitons per NPL, which is shown in the top axis of Fig. 5a. We observe significant NLQ at average excitation densities much lower than 1 exciton pr. NPL, which is clear experimental evidence that excitons are able to diffuse between NPLs in the film. Therefore, using a model with a constant EEA coefficient is not theoretically founded.

From the fits to the NLQ traces and using published values for the PL decay times, we are able to extract values for \(Q_2\) and \(\kappa _2\) for both materials which are presented in Table 1. The \(\kappa _2\) found for BGO is consistent with values for other scintillators exhibiting second order quenching such as CsI:Tl and NaI:Tl with \(\kappa _2\) also in the order of \(10^{-15}\,\hbox {cm}^{3}\hbox {s}^{-0.5}\)15. We can use the fitted value of \(\kappa _2\), the volume of each NPL, \(V_{\text {NPL}}\), and \(a = {5}\,\hbox {nm}\) (see supporting information Eq. (S14)) to estimate the 1D diffusion coefficient for excitons in the NPL film to be \({0.04}\,\hbox {cm}^{2}\,\hbox {s}^{-1}\). This is somewhat smaller than the value of \({0.2}\,\hbox {cm}^{2}\,\hbox {s}^{-1}\) reported for 5.5 ML CdSe core-only NPLs39, however, this difference can probably be attributed to a higher stokes shift in the 4.5 ML NPLs and the fact that the irregular CdS crown could make the self-assembled stacks more disordered. Previous studies of 4.5 ML CdSe/CdS core/crown NPLs in solution have found constant EEA coefficients around \(10\times 10^{-4}\,\hbox {cm}^{2}\,\hbox {s}^{-1}\)9,25,34, which is supported by theoretical calculations19. Using the NPL thickness of 1.364 nm45, this value can be converted to a 3D excitation density which predicts \(Q_2 = 1.36\times 10^{-10}\,\hbox {cm}^{3}\hbox { s}^{-1}\). This suggests that the EEA coefficient is over 50 times larger for the NPL film than typical values for NPLs in solution. This is backed by preliminary z scan measurements of NPLs in solution which show lower rates of EEA compared to a drop cast film (see Supporting Information Section VI). To further underline this point, we plot the predicted NLQ trace for NPLs in solution in Fig. 5a. Inserting the predicted NLQ trace for the NPLs in solution in Eq. (11), the effective nonlinear luminescence efficiency increases almost 10 fold.

When fitting the second order model, Eq. (7), to the observed NLQ trace of BGO, it proved impossible without adding a substantial, flat background of \(14.5\%\) of the signal at low excitation density. However, background measurements indicate a count rate due to laser leakage of \(\le 1\%\), which means that there must be a discrepancy between the model and the data. This is illustrated in Fig. 5b, where the observed NLQ traces are shown alongside fits on the form of Eq. (7) without adding the constant background. A possible explanation is that the expression for \(k_2(t)\) in Eq. (6) breaks down at high excitation densities as it can only be assumed to be valid if there are no more than two excitons per sphere of radius \(R_{dd}\)14. This occurs at excitation densities higher than \(2.4\times 10^{18}\,\hbox {cm}^{-3}\) for BGO, and when looking at the NLQ trace of BGO, this value roughly coincides with where the fit starts to deviate from the data.

The excitation density distribution

In order to use the observed NLQ traces to make a prediction on the light yield, we need a distribution of excitation densities in the material resulting from interaction with ionizing radiation. Few such distributions have been published, and we choose to use one simulated for \(\gamma\)-ray deposition in YAG, published in29, over other materials such as CsI and NaI, both published in46. This choice is based on the electronic stopping power of YAG being in between that of CdSe and BGO for electron energies below 600 keV.

The distribution of excitation densities expected in the NPLs in an ionizing radiation detection system will depend heavily on the choice of detector geometry. If the detector is designed with the intent of measuring luminescence from the NPLs resulting from direct exposure to ionizing radiation, e.g. while embedded in a polymer matrix, we should expect a distribution similar to the one shown in Fig. 4b. However, if the NPLs are combined with a high-Z material and designed to emit upon excitation from secondary electrons, the distribution would shift towards higher excitation densities. Based on our data, the NPLs will be utilized best in a detector geometry that favors lower excitation densities. Further numerical studies into the energy deposition of ionizing radiation in nanocomposite dense media would improve the light yield estimate obtained using the method introduced in this paper, which is currently limited by a lack of available excitation density distributions.

Outlook and future research

The results in this paper motivates research into methods that could reduce the diffusion-enhanced EEA in drop cast films, e.g., by spatially separating the NPLs by embedding them in polystyrene or further concentrating the excitons in the NPL core by growing larger crowns. Diffusion-enhanced EEA could explain why we predict a much higher LY for the CdSe/CdS core/crown NPLs than previously measured 200 ph/MeV47, since these samples had their ligands stripped before deposition thus increasing the density but also possibly the NLQ. However, this underlines the fact that TOF-PET applications require a dense detector medium, which means that attempts to reduce diffusion-enhanced EEA cannot solely rely on spatially diluting the NPLs.

Another avenue of future research would be to compare the NLQ traces of different CdSe/CdS NPL samples or possibly other nanoscintillator materials. It has recently been documented how changes to the nanoparticle size and nanoscale geometry, e.g. core/shell/core- against core/shell quantum dots, have potentially dramatic effects on their radioluminescent properties42,48. We believe the methods presented in this paper can be used to further the development of new- and fine-tuning of existing nanoscintillator materials in a closely packed configuration relevant for TOF-PET.

As a final result, we are also able to estimate the linear luminescence efficiency of the NPL films. For BGO, assuming a phonon-factor of 2.549, the average energy required to create an electron-hole-pair is around 10.75 eV, and when combined with the reported LY, this yields a luminescence efficiency of 9.1 %. Since we know the nonlinear contribution, it is possible to estimate the linear luminescence efficiency of BGO to be around 36%. Using this value for BGO and the factor 1.28 difference in their linear response, predicts a linear luminescence efficiency of the drop cast NPL films of 47%. Such a quantum efficiency is lower than the PLQE measured in solution which is reported to be around 82%. This suggests that the deposition into a closely packed thin film also lowers the linear luminescence efficiency which opens up yet another avenue for possible improvements to the performance of the NPL films. A summary of the calculated linear- and effective nonlinear luminescence efficiencies of the samples studied in this paper are presented in Table 2.

Conclusion

The main conclusion to be drawn from this study is that we demonstrate a method to probe the NLQ of nanomaterials under high density optical excitation. This is motivated by the lack of other experimental methods to understand the optical response of nanomaterials to 511 keV gamma-ray excitation. The data obtained with this method combined with numerical simulations of ionizing radiation energy deposition can conceivably open up a fast and efficient way of evaluating the light yield of nanomaterials in conditions not accessible through other experimental means. Assuming a distribution of excitation resulting from interaction with ionizing radiation, we estimate a light yield of 4.5 ML CdSe/CdS core/crown NPLs in drop cast films of upwards of 2000 photons/MeV which is a promising result compared to previous estimates which were found using X-ray excitation. This encourages further studies into the optical response of NPLs at dense excitation where variations in the NPL geometry and deposition method should be investigated.

We also demonstrate that the method provides a pathway to understanding the nature of luminescence and quenching mechanisms of both wide bandgap bulk scintillators and nanoscintillators. It specifically provides a method to determine the second order quenching term, which is tightly linked to the optical performance of the material at high excitation densities. Comparing the measured NLQ trace for NPLs in drop cast films with previous measurements of the same material in solution, we observe enhanced nonlinear quenching in the films which we attribute to diffusion-enhanced exciton-exciton annihilation. Combined with an apparent reduction in the linear luminescence efficiency, our study points to the NPLs having a potential light yield upwards of 20 times higher than what is reported in this study. To conclude, CdSe/CdS nanoplatelets show a large untapped potential as luminescence centers capable of surpassing the 10 photons/MeV/ps benchmark.

Methods

Optical setup

The photon source for the z-scan luminescence measurements is a Ti:sapphire laser with a repetition rate of 5 kHz, a pulse length of 40 fs, and a broad emission spectrum (\(\text {FWHM}\sim 25\,\)nm) centered around 800 nm. The higher harmonics are generated in \(\beta\)-Barium Borate crystals and they are separated from the fundamental by coated fused silica flat harmonic separators.

PL of the drop cast films in the z-scan setup is measured with an ET Enterprises 9107B PMT while fluctuations in the power of the incoming optical pulses are monitored with a beam sampler directing part of the beam to a Thorlabs DET10A/M biased Si photodiode. To minimize background contamination, the z-scan luminescence measurements are conducted in an optical enclosure which allows for an optical filter setting to account for the broad emission spectrum of BGO. The filter setting on the PMT consists of a 750 nm short-pass filer, a 450 nm long-pass filter, and a \(405\pm 20\,\hbox {nm}\) notch filter. The PMT voltage is set at 650 V and the analogue signals from both the PMT and photodiode are digitized and integrated using a CAEN 730B Digitizer which allows for pulse-to-pulse measurements of the emitted light and the energy of the excitation pulse. The measurement time for each lens position is chosen to be 1 s which corresponds to 5000 optical pulses.

Beam profiles are measured using a Thorlabs BP209-VIS/M scanning slit beam profiler.

Measurements of PL in single photon counting mode is done with a PicoQuant PMA07 Hybrid PMT.

Materials used

The 4.5 monolayer (ML) CdSe/CdS core/crown NPLs studied in this paper were synthesized in a two-step procedure, as described in ref.21.

The absorption and PL spectra for the core/crown and core-only NPLs in solution presented in Fig. 3d were measured with a Perkin Elmer LAMBDA 365+ UV/Vis Spectrometer and an Edinburgh Instruments FLSP920 UV–vis–NIR spectrofluorometer, respectively. PL measurements used a 450 W xenon lamp at an excitation wavelength of 400 nm. PLQE of the core/crown NPLs in solution was measured with the same equipment as was used for PL measurements of the NPLs in solution using an integrating sphere.

The height profile of the drop cast film presented in Fig. 3c is measured with a Dektak XT Surface Profile Measuring System.

The BGO sample studied in this paper is a 1 cm3 cube with all six faces polished and grown by EPIC43 using the Bridgman technique.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon request. Please contact the corresponding author.

References

Ithurria, S. & Dubertret, B. Quasi 2d colloidal cdse platelets with thicknesses controlled at the atomic level. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 16504–5. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja807724e (2009).

Ithurria, S. et al. Colloidal nanoplatelets with two-dimensional electronic structure. Nat. Mater. 10, 936–941 (2011).

Moreels, I. Colloidal nanoplatelets: Energy transfer is speeded up in 2d. Nat. Mater. 14, 4246. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4246 (2015).

Nasilowski, M., Mahler, B., Lhuillier, E., Ithurria, S. & Dubertret, B. Two-dimensional colloidal nanocrystals. Chem. Rev. 116, 10934–10982 (2016).

Tomar, R. et al. Charge carrier cooling bottleneck opens up nonexcitonic gain mechanisms in colloidal cdse quantum wells. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 9640–9650. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b02085 (2019).

García Flórez, F., Kulkarni, A., Siebbeles, L. D. A. & Stoof, H. T. C. Explaining observed stability of excitons in highly excited cdse nanoplatelets. Phys. Rev. B 100, 245302. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.100.245302 (2019).

Grim, J. Q. et al. Continuous-wave biexciton lasing at room temperature using solution-processed quantum wells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 891–895. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2014.213 (2014).

Rowland, C. E. et al. Picosecond energy transfer and multiexciton transfer outpaces auger recombination in binary cdse nanoplatelet solids. Nat. Mater. 14, 484–489. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4231 (2015).

Rodà, C. et al. Colloidal cdse/cds core/crown nanoplatelets for efficient blue light emission and optical amplification. Nano Lett. 23, 3224–3230. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c05061 (2023).

Sigle, D. O., Zhang, L., Ithurria, S., Dubertret, B. & Baumberg, J. J. Ultrathin cdse in plasmonic nanogaps for enhanced photocatalytic water splitting. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 1099–1103 (2015).

Turtos, R. M. et al. On the use of CdSe scintillating nanoplatelets as time taggers for high-energy gamma detection. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 3, 37 (2019).

Lecoq, P. On the way to the 10 ps time-of-flight pet challenge. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 137, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/s13360-022-03159-8 (2022).

Kwon, S. I. et al. Ultrafast timing enables reconstruction-free positron emission imaging. Nat. Photonics 15, 914–918. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-021-00871-2 (2021).

Kirm, M. et al. Exciton-exciton interactions in cdwo4 irradiated by intense femtosecond vacuum ultraviolet pulses. Phys. Rev. B 79, 233103 (2009).

Grim, J. Q. et al. Nonlinear quenching of densely excited states in wide-gap solids. Phys. Rev. B 87, 5117. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.87.125117 (2013).

Williams, R. T. et al. Scintillation Detectors of Radiation: Excitations at High Densities and Strong Gradients, 299–358 (Springer Singapore, Singapore, 2015).

Belsky, A. et al. Time-resolved luminescence z-scan of csi using power femtosecond laser pulses. Radiat. Meas. 124, 1–8 (2019).

Spassky, D. et al. Excitation density effects in luminescence properties of camoo4 and znmoo4. Opt. Mater. 90, 7–13 (2019).

Steinhoff, A., Jahnke, F. & Florian, M. Microscopic theory of exciton-exciton annihilation in two-dimensional semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 104, 155416 (2021).

Bertrand, G. H., Polovitsyn, A., Christodoulou, S., Khan, A. H. & Moreels, I. Shape control of zincblende cdse nanoplatelets. Chem. Commun. 52, 11975–11978 (2016).

Leemans, J. et al. Near-edge ligand stripping and robust radiative exciton recombination in cdse/cds core/crown nanoplatelets. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 3339–3344. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c00870 (2020).

Krause, P., Rogers, E. & Bizarri, G. Advances in design of high-performance heterostructured scintillators for time-of-flight positron emission tomography. Adv. Theory Simul. 7, 425. https://doi.org/10.1002/adts.202300425 (2023).

Tessier, M. D. et al. Efficient exciton concentrators built from colloidal core/crown cdse/cds semiconductor nanoplatelets. Nano Lett. 14, 207–213. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl403746p (2014).

Kelestemur, Y. et al. Platelet-in-box colloidal quantum wells: Cdse/cds@cds core/crown@shell heteronanoplatelets. Adv. Func. Mater. 26, 3570–3579. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201600588 (2016).

Tomar, R. et al. Charge carrier cooling bottleneck opens up nonexcitonic gain mechanisms in colloidal cdse quantum wells. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 9640–9650. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b02085 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Uniform thickness and colloidal-stable cds quantum disks with tunable thickness: Synthesis and properties. Nano Res. 5, 337–351 (2012).

Achtstein, A. W. et al. Linear absorption in cdse nanoplates: Thickness and lateral size dependency of the intrinsic absorption. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 20156–20161 (2015).

Antonangeli, F., Zema, N., Piacentini, M. & Grassano, U. M. Reflectivity of bismuth germanate. Phys. Rev. B 37, 9036–9041. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.37.9036 (1988).

Belsky, A. et al. Mechanisms of luminescence decay in yag-ce, mg fibers excited by \(\gamma\)-and x-rays. Opt. Mater. 92, 341–346 (2019).

Delport, G. et al. Exciton-exciton annihilation in two-dimensional halide perovskites at room temperature. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 5153–5159. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b01595 (2019).

Sortino, L. et al. Radiative suppression of exciton–exciton annihilation in a two-dimensional semiconductor. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 202. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-023-01249-5 (2023).

Zheng, Y., Venkatesh, R., Rojas-Gatjens, E., Reichmanis, E. & Silva-Acuña, C. Exciton bimolecular annihilation dynamics in push-pull semiconductor polymers. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 272–280 (2024).

Engel, E., Leo, K. & Hoffmann, M. Ultrafast relaxation and exciton-exciton annihilation in ptcda thin films at high excitation densities. Chem. Phys. 325, 170–177 (2006).

Kunneman, L. T. et al. Bimolecular auger recombination of electron-hole pairs in two-dimensional cdse and cdse/cdzns core/shell nanoplatelets. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 3574–3578 (2013).

Tessier, M. D. et al. Phonon line emission revealed by self-assembly of colloidal nanoplatelets. ACS Nano 7, 3332–3340 (2013).

Jana, S. et al. Stacking and colloidal stability of cdse nanoplatelets. Langmuir 31, 10532–10539 (2015).

Guzelturk, B. et al. Nonradiative energy transfer in colloidal cdse nanoplatelet films. Nanoscale 7, 2545–2551 (2015).

Wen, Z. et al. Ultrapure green light-emitting diodes based on cdse/cds core/crown nanoplatelets. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 56, 1–6 (2019).

Liu, J., Guillemeney, L., Abécassis, B. & Coolen, L. Long range energy transfer in self-assembled stacks of semiconducting nanoplatelets. Nano Lett. 20, 3465–3470 (2020).

Vasil’ev, A. N. From luminescence non-linearity to scintillation non-proportionality. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 55, 1054–1061. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.2007.914367 (2008).

Shornikova, E. V. et al. Exciton binding energy in cdse nanoplatelets measured by one-and two-photon absorption. Nano Lett. 21, 10525–10531 (2021).

Guzelturk, B. et al. Bright and durable scintillation from colloidal quantum shells. Nat. Commun. 15, 4274 (2024).

Epic crystal.

Shim, J. et al. Luminescence, radiation damage, and color center creation in eu 3+-doped bi 4 ge 3 o 12 fiber single crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 93, 5131–5135 (2003).

She, C. et al. Low-threshold stimulated emission using colloidal quantum wells. Nano Lett. 14, 2772–2777 (2014).

Korzhik, M., Tamulaitis, G. & Vasil’ev, A. N. Physics of fast Processes in Scintillators Vol. 262 (Springer, 2020).

Martinez Turtos, R., Gundacker, S., Omelkov, S., Auffray, E. & Lecoq, P. Light yield of scintillating nanocrystals under x-ray and electron excitation. J. Lumin. 215, 116613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2019.116613 (2019).

Fratelli, A. et al. Size-dependent multiexciton dynamics governs scintillation from perovskite quantum dots. Adv. Mater. 37, 2413182 (2025).

Gektin, A. & Vasil’ev, A. Scintillation, phonon and defect channel balance, the sources for fundamental yield increase. Funct. Mater. (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research has been funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.J. developed and constructed the experimental setups used for the z-scan luminescence measurements, conducted the experiments, and performed the data analysis and visualization. A.D.G. synthesized the NPLs and measured absorption spectra, PL spectra and PLQE of the NPLs in solution. I.M., B.J., R.M.T. contributed significantly to the methodology, analysis, and writing process. R.M.T. conceived the ideas that motivated this study. S.J. and R.M.T. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed and edited this manuscript leading to its final form.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jessen, S., Di Giacomo, A., Moreels, I. et al. Nonlinear quenching of excitonic emission from nanoplatelet films at high excitation densities. Sci Rep 15, 23423 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04572-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04572-6