Abstract

The findings on the connection between Alzheimer’s disease and the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) are inconsistent. Additionally, the relationship between Alzheimer’s and the DASH diet has not been explored in the Middle East region. This case-control study aimed to evaluate the association between adherence to DASH diet and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. The study included 212 participants (106 cases and 106 controls). Cases were recruited among people in the early stages of the disease who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease within the past six months. Controls were selected from health centers across Tehran. Dietary intake was assessed using a validated 168-item food frequency questionnaire. Four DASH diet indices (Dixon, Mellen, Fung, and Günther) were used to evaluate the adherence. After adjusting for potential confounders, higher adherence to Günther’s, Mellen’s, and Fung’s DASH diet indices were significantly associated with a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease (Mellen’s OR: 0.29; 95% CI: 0.10–0.83; Fung’s OR: 0.22; 95% CI: 0.08–0.65; Günther’s OR: 0.36; 95% CI: 0.13–1.00). Adherence to DASH dietary pattern might be associated with a decreased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Future studies should aim to investigate the association in a prospective design in the Middle East.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dementia ranks among the top causes of disability and death1,2. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia3,4. The global prevalence of Alzheimer’s is expected to double, surpassing 100 million cases by 20505,6,7, imposing a trillion-dollar burden on patients and the healthcare system8,9,10. In Iran, prevalence of dementia among older adults is roughly estimated at 8%, rising to 14% in the central regions11,12,13.

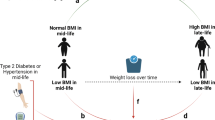

Pro-inflammatory diets, including those high in saturated fats and sugar, can exacerbate the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques in the brain, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s14,15,16. Conversely, anti-inflammatory diets, which are rich in fruits, vegetables and healthy fats, may reduce the risk and slow the progression of disease14,17,18.

While the majority of research has concentrated on specific foods and nutrients19,20,21,22, examining whole dietary patterns could bypass the constraints of focusing on isolated foods or nutrients23,24,25. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), primarily designed to combat high blood pressure, may also affect Alzheimer’s risk26. This diet promotes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins while limiting salt, red meat, and sweets26,27.

Number of studies investigating the relationship between DASH diet and Alzheimer’s risk is limited and outcomes are severely conflicting28,29,30,31. Two studies revealed a significant reduction in Alzheimer’s risk with higher adherence to DASH diet29,30. Conversely, some reports did not find any significant association28,31.

The research explores a crucial public health issue by investigating the link between adherence to the DASH diet and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease within a Middle Eastern population—an area that has received limited attention in prior studies. Specifically, it compares four distinct DASH diet indices, which strengthens the study’s methodological contribution and ensures a comprehensive assessment of dietary patterns. To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the association of four DASH diet indices with risk of Alzheimer.

Methods

Subjects

This case-control study focused on Alzheimer’s patients admitted to the Iran Alzheimer and Dementia Association in Tehran, Iran, between September 2023 and June 2024. The required sample size for this research was determined based on the data provided by Filippini et al. A significance level (α) of 0.05, a power of 0.8, an odds ratio (OR) of 0.66, and a control-to-case ratio of 1 were employed, resulting in a calculated sample size of 106 cases and 106 control participants.

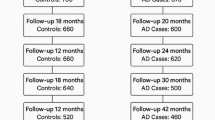

Only those diagnosed by the center’s neurologist based on Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS) score32, with no history of other cognitive disorders, were classified as Alzheimer’s patients. Eligible cases included all new Alzheimer’s cases from the past six months, provided their caregiver was available during the interview. Exclusion criteria included patients whose disease had progressed beyond the fourth stage of the Reisberg Functional Assessment Staging scale33, caregivers lacking knowledge of the patient’s diet before diagnosis, and patients with special dietary habits, such as being vegetarian. (Fig. 1)

The control group was randomly selected from visitors at six health centers across different parts of the city, following an examination by center’s physician and filling out 3MS questionnaire by a trained interviewer in order to rule out any cognitive disorders. Exclusion criteria for controls included a history of any physician-diagnosed cognitive disorder, a 3MS score lower than 7832 and special dietary habits. Participants were matched based on their sex and age. The overall participation rate was 92%. Out of 214 eligible subjects, a case subject was excluded due to daily energy intakes being more than three standard deviations from the mean. Additionally, one control subject was excluded since her dietary data lacked necessary items to calculate DASH diet indices. Finally, 212 subjects (106 cases and 106 controls) were included in the final analysis. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment. All procedures adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the findings were reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for case-control studies.

Dietary assessment

We employed a validated 168-item semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) with multiple-choice frequency response options to evaluate the usual dietary intakes of all participants. The reproducibility and relative validity of this FFQ in assessing major dietary patterns and food and nutrient intake among Iranian adults have been previously established34. Caregivers were asked to report how often specific portions of various foods were consumed on a daily, weekly, monthly, or yearly basis during the year prior to the Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis (for cases) or their visit of the health centers (for controls). Household measures were used to convert these portion sizes into grams. The specified portion size, dish composition, and the average reported frequency (e.g., divided by 30 for monthly consumption) were considered to calculate the daily intake for each food item. To determine the nutrient intakes from the FFQ, the modified Nutritionist IV software was utilized, which was adapted to include Iranian foods in the original USDA food composition table.

The DASH scores

The inclusion of four distinct DASH diet indices allows for a comprehensive analysis of adherence to the DASH diet and its association with Alzheimer’s disease risk. Each index captures different aspects of dietary patterns or scoring methodologies, providing a multidimensional perspective that strengthens the robustness and validity of the findings. This approach also aligns with prior research exploring variations in DASH diet adherence across different populations, ensuring a deeper understanding of its applicability in a Middle Eastern setting35. These scores were derived from the indices established by Mellen, Fung, Dixon, and Günther36,37,38,39. Table S1 outlines the scoring criteria and points for each index. Dixon’s DASH diet index comprises 8 food groups and one nutrient: total fruits, total vegetables, whole grains, total dairy products, nuts/seeds/legumes, meat/meat equivalents, added sugar, saturated fat, and alcohol. Each category is worth one point, with a total possible score ranging from 0 to 9. In our study, the alcohol component was excluded from Dixon’s DASH score due to religious considerations. The recommended daily energy intake cut-offs were set at 1600 kcal for women and 2000 kcal for men. Details on the calculation of Mellen, Fung, and Günther DASH score can be found in the supplementary information. (Additional file 1)

Data collection

Caregivers were interviewed by skilled interviewers to provide data on socio- economic and demographic variables, history of cognitive disorders and other diseases, family history of Alzheimer’s disease, daily sleep duration, and current or past smoking behavior. Physical activity levels were assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire and subsequently quantified as metabolic equivalent scores (MET-min-week-1)40. To measure weight, we used a digital scale (Seca, Germany) with subjects minimally clothed and without shoes, recorded to the nearest 100 g. Height was measured with a wall-mounted stadiometer (Seca, Germany) to a precision of 2 mm, with participants also barefoot. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the ratio of weight (in kilograms) to the square of height (in meters). Economic score was calculated using family income, and house ownership41.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Significance tests were conducted with a confidence interval of at least 95% (p-value ≤ 0.05). The normality of variables was checked, employing the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The chi-square test examined the relationships between categorical variables. To analyze the association between continuous variables, either the Mann-Whitney test or the independent samples T-test was used. The DASH scores (Dixon’s, Mellen’s, Fung’s, and Günther’s) were analyzed as distribution-based indices, with the lowest tertile serving as the reference category. Unconditional logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals for DASH diet index categories or tertiles and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in multivariate adjusted models. These models were adjusted for age at diagnosis (year), BMI (kg/m2), energy intake (kcal/d), daily sleep (hour), number of children, and family history of Alzheimer’s. Additionally, Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated to compare total scores across the four indices.

Results

Table 1 outlines the demographic details of the study group. Control group had significantly higher height, weight, and BMI. Conversely, the case group had significantly higher sleep hours, number of children, and energy intake. Additionally, participants in the case group reported a higher incidence of family history of Alzheimer’s disease.

Table S2 and S3 present the baseline characteristics based on the categories or tertiles of total DASH scores for all indices. Individuals with higher scores across all indices generally had higher energy intake. The exceptions were Mellen’s index, which adjusts for energy, and Gunther’s index, which varies based on different energy intake levels. Additionally, the economic score was notably higher for those with high scores on Dixon and Fung’s index. Also, people with fewer children or no history of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) were more likely to get higher scores in Dixon and Fung’s index.

Table 2 shows the relationships between the total scores of various DASH indices. The correlation coefficients varied from 0.22 to 0.62. The strongest correlation was found between Fung’s and Günther’s indices (r = 0.62), whereas the weakest was between Dixon’s and Mellen’s DASH indices (r = 0.22).

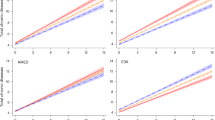

The ORs and their 95% CI for total DASH scores and risk of Alzheimer’s disease are shown in Fig. 2 and Table S4. After accounting for potential confounders, we observed a significant trend across the tertiles of dietary intake for three DASH diet indices, Mellen’s, Fung’s and Günther’s, with P-trend values of 0.01, 0.002, and 0.03, respectively. Moreover, individuals in the highest tertiles of both Mellen’s and Fung’s scores had a 71 and 78% lower OR of Alzheimer’s disease compared to those in the lowest tertiles (Mellen’s OR: 0.29; 95% CI: 0.10–0.83; Fung’s OR: 0.22; 95% CI: 0.08–0.65). Finally, the trend in OR was not statistically significant for Dixon’s index (P-trend: 0.07). Furthermore, a gender-based subgroup analysis revealed a significant reduction in the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, observed exclusively among individuals in the highest tertile of Fung’s DASH score (OR: 0.20; 95% CI: 0.04–0.98) (Table 3). Nevertheless, some Odds Ratios with 95% Confidence Intervals approach significance, their interpretation warrants caution due to the potential for variability (Table S4). This variability may arise from sampling limitations or underlying biases, emphasizing the need for careful consideration when drawing conclusions from these findings.

Crude and adjusted ORs (95% CIs) for Alzheimer’s disease by tertiles of DASH diet index scores. Basic model adjusted for age at diagnosis, sex and BMI. Multivariate model adjusted for age at diagnosis, BMI, energy intake, sleep per day, number of children and family history of Alzheimer. *p ≤ 0.05 considered as significant.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first observational study that explores the relationship between four DASH diet indices and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. In this case-control study, we discovered that higher adherence to three of the four DASH indices (Günther’s, Mellen’s and Fung’s) was significantly linked to a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease. However, we failed to find a significant relation between the trend of OR and Dixon’s index.

This variation in results could be attributed to the differences in scoring methodologies and sensitivity to capturing dietary adherence trends35,36,42. Mellen’s index focuses on specific nutrient targets (e.g., potassium, magnesium, fiber) and penalizes deviations from optimal nutrient intake35,39. Its precision in quantifying nutrient adherence may contribute to its significant association with reduced Alzheimer’s disease risk. Fung’s index, conventional scoring, emphasizes on food components, allowing the identification of dietary patterns with high adherence to DASH principles35,37. Its quintile-based categorization of intake may capture broader variations across individuals, leading to stronger associations35. Günther’s Index is a more intricate food-based scoring system that assesses adherence across a variety of components38. This index’s higher granularity may better identify adherence patterns, correlating significantly with Alzheimer’s risk reduction35,38. Dixon’s index, while also food-based, has fewer components compared to Günther’s along with a rigid scoring system36. This simpler structure may be less sensitive in detecting adherence trends, contributing to the lack of significant association35,36.

Current evidence linking the DASH diet to risk of Alzheimer’s disease is limited. In line with our findings, after more than 4 years of follow-up, the Memory and Aging Project found that individuals with the highest adherence to the DASH diet had a significantly lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease29. Additionally, those in the highest tertile of DASH adherence experienced a slower decline in overall cognitive function. The study also showed that a continuous DASH score was linked to a slower rate of decline in global cognition, episodic memory, and semantic memory30. Meanwhile, Shakersain et al. failed to find a significant association between DASH score and cognitive decline in Swedish population28. However, this might be the result of using a summarized version of FFQ that could have missed some influential items28,43. Moreover, reports from a study from Spain, investigating the association between adherence to DASH diet with cognitive performance, indicated no significant relation between Fung’s DASH index and variations in cognitive function31. Although Nishi et al.31, focused on individuals with a mean age of 65 years and reported results following a 2-year follow-up period, its participants were predominantly recruited from populations with obesity or overweight conditions. This recruitment criterion likely influenced the outcomes of their dietary assessment and restricted the generalizability of their findings. In contrast, our study demonstrated significant associations across tertiles of dietary intake for three DASH diet indices (Mellen’s, Fung’s, and Günther’s) and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, with P-trend values of 0.01, 0.002, and 0.03, respectively (Fig. 2; Table S4). Similarly, while Daniel et al.44 found no significant association between Fung’s DASH index and cognitive decline or performance, in our study individuals in the highest tertiles of Fung’s DASH score exhibited a remarkable reduction in risk—78% (OR: 0.22; 95% CI: 0.08–0.65). This divergence could reflect differences in the study populations or dietary assessment methodologies, underscoring the need for further investigation into these relationships.

On the contrary, Wengreen et al. reported a significant association between quintiles of adherence to DASH diet and better average cognition among adults aged over 65 years24. Likewise, Haring et al. reported Higher quintile of DASH score significantly associated with lower risk of mild cognitive impairment in older people after over 9 years of follow-up45.

The precise mechanisms by which DASH affects risk of Alzheimer’s disease are gradually coming to light. Whole grain, vegetables, fruits, legumes, and nuts are rich in essential nutrients and bioactive compounds that possess anti-inflammatory and antioxidant qualities. Also, some of these nutrients, including B vitamins, affect the balance of neurotransmitters and epigenic regulations17,46,47,48. These properties are believed to help reduce oxidative stress in the brain, support the growth of new neurons, and enhance neuronal connectivity17,46,47,49. Furthermore, by limiting the intake of sweets and processed meat in the DASH diet, the harmful effects of high fat and sugar on the formation of beta amyloid protein and brain inflammation can be reduced50. Additionally, Diet-induced changes to the gut microbiome could also play a role, as suggested by a previous New York university women’s health study that identified an increase in pro-inflammatory gut bacteria in women who reported higher cognitive complaints51,52. Finally, since hypertension is a known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, the DASH diet’s influence on blood pressure regulation could explain the results53.

The primary strength of our study lies in the comparison of four different DASH diet indices for the same outcome. Additionally, to eliminate the chance of diet al.teration due to Alzheimer’s disease or diagnosis, we exclusively enrolled patients in the early stages of the disease who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease within the past six months. The study’s strengths also included a high participation rate among subjects and an analysis adjusted for confounding variables. However, our research has several limitations. Firstly, due to the case-control design, there is a potential for recall bias. Participants diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers might remember their past diets differently, which could lead to an overestimation of associations. Secondly, selection bias is a concern in retrospective case-control studies. In our study, we minimized this risk by ensuring high participation rates and selecting control participants from various health centers across the city, representing different socio-economic backgrounds. Another limitation is the lack of precision in our results, attributed to the small sample size. Additionally, despite using a validated food-frequency questionnaire to assess dietary intake, measurement errors were unavoidable, potentially causing underestimation or overestimation of associations34. Future prospective studies are necessary to clarify the role of different aspects of the four DASH diet indices in predicting Alzheimer’s risk and to establish a standardized DASH diet index for these patients.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings indicated that adherence to DASH diet was associated with a decreased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. However, it is important to note that slight differences among the scoring methods can influence the outcomes, which should be considered in future studies.

Data availability

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Collaborators, G. B. D. Global mortality from dementia: application of a new method and results from the global burden of disease study 2019. Alzheimer’s Dementia: Translational Res. Clin. Interventions 7(1), e12200 (2021).

Wimo, A. et al. The worldwide costs of dementia in 2019. Alzheimer’s Dement. 19(7), 2865–2873 (2023).

Breijyeh, Z. & Karaman, R. Comprehensive review on alzheimer’s disease: causes and treatment. Molecules 25(24), 5789 (2020).

Scheltens, P. et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 397(10284), 1577–1590 (2021).

Rajan, K. B. et al. Population estimate of people with clinical alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in the united States (2020–2060). Alzheimers Dement. 17(12), 1966–1975 (2021).

Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia. In 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public. Health. 7(2), e105–e125 (2022).

Nichols, E. & Vos, T. The Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia from 1990–2019 and forecasted prevalence through 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease (GBD) study 2019. Alzheimer’s Dement. 17(S10), e051496 (2021).

Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 19(4), 1598–1695 (2023). (2023).

Jetsonen, V. et al. Total cost of care increases significantly from early to mild alzheimer’s disease: 5-year ALSOVA follow-up. Age Ageing. 50(6), 2116–2122 (2021).

Wong, W. Economic burden of alzheimer disease and managed care considerations. Am. J. Manag Care. 26(8 Suppl), S177–s183 (2020).

Oshnouei, S., Safaralizade, M., Eslamlou, N. F. & Heidari, M. Uncovering the extent of dementia prevalence in iran: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public. Health. 24(1), 1168 (2024).

Aajami, Z., Kebriaeezadeh, A. & Nikfar, S. Direct and indirect cost of managing alzheimer’s disease in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Iran. J. Neurol. 18(1), 7–12 (2019).

Navipour, E., Neamatshahi, M., Barabadi, Z., Neamatshahi, M. & Keykhosravi, A. Epidemiology and risk factors of alzheimer’s disease in iran: A systematic review. Iran. J. Public. Health. 48(12), 2133–2139 (2019).

Xu Lou, I., Ali, K. & Chen, Q. Effect of nutrition in alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Frontiers Neuroscience 17 (2023).

Akiyama, H. et al. Inflammation and alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 21(3), 383–421 (2000).

Kinney, J. W. et al. Inflammation as a central mechanism in alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. (N Y). 4, 575–590 (2018).

McGrattan, A. M. et al. Diet and inflammation in cognitive ageing and alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 8(2), 53–65 (2019).

Vasefi, M., Hudson, M. & Ghaboolian-Zare, E. Diet associated with inflammation and alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 3(1), 299–309 (2019).

Ge, M. et al. Role of calcium homeostasis in alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis. Treat. 18, 487–498 (2022).

Lloret, A., Esteve, D., Monllor, P., Cervera-Ferri, A. & Lloret, A. The Effectiveness of Vitamin E Treatment in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J. Mol. Sci 20(4) (2019).

Lauer, A. A. et al. Mechanistic Link between Vitamin B12 and Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 12(1) (2022).

Socha, K. et al. Dietary habits, selenium, copper, zinc and total antioxidant status in serum in relation to cognitive functions of patients with alzheimer’s disease. Nutrients. 13(2), 287 (2021).

Berendsen, A. M. et al. Association of long-term adherence to the Mind diet with cognitive function and cognitive decline in American women. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 22(2), 222–229 (2018).

Wengreen, H. et al. Prospective study of dietary approaches to stop Hypertension– and Mediterranean-style dietary patterns and age-related cognitive change: the cache County study on memory, health and Aging123. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98(5), 1263–1271 (2013).

BETTER, M. A. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 20, 3708–3821 (2024).

Theodoridis, X. et al. Adherence to the DASH diet and risk of hypertension: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 15(14), 3261 (2023).

Ellouze, I., Sheffler, J., Nagpal, R. & Arjmandi, B. Dietary Patterns and Alzheimer’s Disease: An Updated Review Linking Nutrition to Neuroscience. Nutrients 15(14) (2023).

Shakersain, B. et al. The nordic prudent diet reduces risk of cognitive decline in the Swedish older adults: A Population-Based cohort study. Nutrients 10(2), 229 (2018).

Morris, M. C. et al. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 11(9), 1007–1014 (2015).

Tangney, C. C. et al. Relation of DASH- and Mediterranean-like dietary patterns to cognitive decline in older persons. Neurology 83(16), 1410–1416 (2014).

Nishi, S. K., Mediterranean, D. A. S. H., Dietary Patterns, M. I. N. D., Cognitive Function. & et al., and The 2-Year longitudinal changes in an older Spanish cohort. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 782067 (2021).

Gharaeipour, M. & Andrew, M. K. Examining cognitive status of elderly iranians: Farsi version of the modified Mini-Mental state examination. Appl. Neuropsychology: Adult. 20(3), 215–220 (2013).

Sclan, S. G. & Reisberg, B. Functional assessment staging (FAST) in alzheimer’s disease: reliability, validity, and ordinality. Int. Psychogeriatr. 4(Suppl 1), 55–69 (1992).

Asghari, G. et al. Reliability, comparative validity and stability of dietary patterns derived from an FFQ in the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Br. J. Nutr. 108(6), 1109–1117 (2012).

Miller, P. E. et al. Comparison of 4 established DASH diet indexes: examining associations of index scores and colorectal cancer123. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98(3), 794–803 (2013).

Dixon, L. B. et al. Adherence to the USDA food guide, DASH eating plan, and mediterranean dietary pattern reduces risk of colorectal adenoma. J. Nutr. 137(11), 2443–2450 (2007).

Fung, T. T. et al. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch. Intern. Med. 168(7), 713–720 (2008).

Günther, A. L. et al. Association between the dietary approaches to hypertension diet and hypertension in youth with diabetes mellitus. Hypertension 53(1), 6–12 (2009).

Mellen, P. B., Gao, S. K., Vitolins, M. Z. & Goff, D. C. Jr. Deteriorating dietary habits among adults with hypertension: DASH dietary accordance, NHANES 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Arch. Intern. Med. 168(3), 308–314 (2008).

Vasheghani-Farahani, A. et al. The persian, last 7-day, long form of the international physical activity questionnaire: translation and validation study. Asian J. Sports Med. 2(2), 106–116 (2011).

Garmaroudi, G. R. & Moradi, A. Socio-economic status in iran: a study of measurement index. Payesh (Health Monitor). 9(2), 137–144 (2010).

Heidari, Z. et al. Dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diets and breast cancer among women: a case control study. BMC Cancer. 20(1), 708 (2020).

Rothenberg, E. M. Experience of dietary assessment and validation from three Swedish studies in the elderly. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 63(Suppl 1), S64–S68 (2009).

Daniel, G. D. et al. DASH diet adherence and cognitive function: Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 46, 223–231 (2021).

Haring, B. et al. No association between dietary patterns and risk for cognitive decline in older women with 9-Year Follow-Up: data from the women’s health initiative memory study. J. Acad. Nutr. Dietetics. 116(6), 921–930 (2016). e1.

Ozawa, M., Shipley, M., Kivimaki, M., Singh-Manoux, A. & Brunner, E. J. Dietary pattern, inflammation and cognitive decline: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 36(2), 506–512 (2017).

Hayden, K. M. et al. The association between an inflammatory diet and global cognitive function and incident dementia in older women: the women’s health initiative memory study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 13(11), 1187–1196 (2017).

Ekstrand, B. et al. Brain foods - the role of diet in brain performance and health. Nutr. Rev. 79(6), 693–708 (2021).

Nilsson, A., Halvardsson, P. & Kadi, F. Adherence to DASH-Style dietary pattern impacts on adiponectin and clustered metabolic risk in older women. Nutrients 11(4), 805 (2019).

Fadó, R., Molins, A., Rojas, R. & Casals, N. Feeding the brain: effect of nutrients on cognition, synaptic function, and AMPA receptors. Nutrients 14(19), 4137 (2022).

Wu, F. et al. Gut microbiota and subjective memory complaints in older women. J. Alzheimers Dis. 88, 251–262 (2022).

David, L. A. et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut Microbiome. Nature 505(7484), 559–563 (2014).

Ungvari, Z. et al. Hypertension-induced cognitive impairment: from pathophysiology to public health. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 17(10), 639–654 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank Iran Dementia and Alzheimer association, Deputy of health from Shahid Beheshti university and Iran university of medical sciences and all the participants for their assistance and cooperation.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MMA participated in the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and final approval of the manuscript. SK, MS, MK and HS carried out the study, participated in data acquisition, and approved final version of the manuscript. MA, FK and SR contributed to conception, design, provided specialized council and approved the final manuscript. BR contributed to conception, design, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content manuscript editing, English editing of our manuscript and final approval of manuscript. He also provided critical feedback for revising the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics board of the National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science approved the study protocol, approval number [IR.SBMU.NNFTRI.REC.1402.027], and a written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrolment in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abbasi, M.M., Khandae, S., Shahabi, M. et al. Association between the DASH diet and Alzheimer’s disease in a case-control study. Sci Rep 15, 23312 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05416-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05416-z