Abstract

Low crop productivity plagues the agricultural sector of the Kallu district, partly due to insufficient extension services. Although ICTs’ can revolutionize agriculture, their adoption and effective application remain low in most rural areas. In response, this study bridges this gap by investigating the preferences and applications of ICTs among farmers within the Kallu district. This research innovates how the demographic, socio-economic, infrastructural, and perceptual factors influence ICT choice and application in the farming cycle. The study employed a cross-sectional design, collecting data from 119 respondents using Cochran’s formula. Primary data was gathered through surveys and focus group discussions, while various academic sources served as secondary data sources. Data analysis involved a pie chart, ANOVA, chi-square, and multinomial logistic regression. The study revealed that farmers utilized technologies throughout the entire sorghum production cycle. Various factors influencing ICT preference: gender (2.1% rise in female usage), education (0.14% decline), electric power access (0.06%), hedonic motivation (0.2%), and price value (0.5%) rise in the choice of Pico. Farm income (0.000596%), electric power access (52.5%), relative advantage (0.57%), and hedonic motivation (15%) positively raise TV selection. Age (5.3% decline) and farm income (0.00154%), network access (65.9%), electric access (34.3%), relative advantage (67.9%), hedonic motivation (44.6%), compatibility (78.2%), and information quality (44.3%) significantly rise mobile phone usage. These findings highlight technologies that support farmers across various stages of agricultural practices. However, demographic, socio-economic, infrastructural, and perceptional factors significantly influence ICT utilization. Based on the research findings, we recommend tailoring ICT provision by delivering information through various channels, and catering to farmers’ diverse needs and circumstances. It is critical to address these influencing factors when designing and implementing ICT-based agricultural interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background and justifications of the study

Information and communication technology (ICT) encompasses hardware, software, networks, and media that facilitate data collection, transmission, and processing1. Utilization of appropriate tools for information sharing is the key to the sustainable growth of agriculture in the twenty-first century2.

Globally, the agricultural sector is faced with challenges of low productivity of crops due to a gap in communication between extension agents and farmers3. Sorghum crops are particularly susceptible to climate change, climate variability, poor soil fertility, and pest and weed issues4. In this respect, ICTs offer a unique opportunity to enhance the availability of information on agricultural management and mitigate the associated risks, which could be converted into high productivity of crops5.

Despite the novel ICTs opportunity, there is a gap in current literature on ICT adoption in Ethiopian agriculture, specifically for a specific crop like Sorghum. Even though some research has been conducted to explore overall ICT adoption and its impact on agricultural productivity, there is lack of research that explores farmers’ specific needs and ICT preferences for producing sorghum. Additionally, the factors influencing the choice of different tools, such as mobile phones, radio, television, and Pico, have not been adequately explored in the Ethiopian context.

As highlighted by Deloitte (2012) cited in6, ICTs are applicable throughout the three key stages of the agricultural production process: pre-cultivation, crop cultivation and harvesting, and post-harvest. While its adoption plays a significant role in agricultural development, various factors influence its utilization. These factors encompass socio-economic, personal, situational, and institutional aspects, along with perceptions regarding ICTs7.

The Kallu district grapples with low crop productivity due to limited access to extension services and credit facilities. Additionally, a gap exists in making valuable information readily available to the farming community through ICT-based agricultural advisory services8. Although the recent introduction of Pico projectors for showcasing locally produced videos represents a positive step, the district lacks research exploring the preference and application of ICT in agricultural production from the farmers’ perspective. This necessitates an analysis of the current situation regarding ICT integration across the farming stages. Furthermore, researchers emphasized the need to investigate the factors influencing ICT choices, focusing on perceptions of tools and information quality7,9,10.

Jointly there are lack of crop-specific research, insufficient understanding of ICT Preferences, lack of research specifically focused on the preferences and application of ICTs in agricultural production from the farmers’ perspective within the Kallu district. Therefore, this research investigated how farmerscurrently prefer and utilize different ICT tools in Kallu District, Wollo, Ethiopia. This study intends to contribute to the existing literature and translate theoretical insights into practical applications by analyzing the application of ICTs across the various stages of the farming cycle within this specific local context and investigating the factors influencing farmers’ choices of ICTs, particularly their perceptions of the tools and the quality of the information received.

Objective of the study

The general objective was investigating farmers preference and utilization of ICT tools in Kallu District, Wollo, Ethiopia. Specifically,

-

1

To analyze the application of ICTs across the Sorghum farming cycle.

-

2

To assess the determinants influencing farmers’ choices of ICTs.

Methodology of the study

Description of the study area

Kallu is selected due to there is a lack of studies in the area regarding ICTs utilization. Kallu district, located in the South Wollo Administrative Zone of Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia (Fig. 1), primarily practices mixed subsistence farming. Sorghum and maize are the dominant cereal crops, occupying a significant portion of the cultivated area. The major cereal crops grown in the area are teff, maize, wheat, and Sorghum. The district’s extension system, similar to others in Ethiopia, is managed by the district agricultural office8.

The population of Kallu district is approximately 227,488 people, with around 16.86% living in urban areas (CSA, 2017), as cited in11. Kallu district is located approximately between 39°40’—41E longitude and 11°06’—11°58’N latitude. The district covers a total area of approximately 851.54 square kilometers. The elevation of Kallu district ranges from about 1400 to 1850 m above sea level in some areas, and in other reports, it’s mentioned to range from 500 to 2700 m above sea level, indicating some variation within the district.

The South Wollo zone, including Kallu, experiences a bimodal rainfall pattern: Belg (short rainy season), typically from mid-February to the end of April. Meher (main rainy season): from mid-June to early September, contributing the majority (65–95%) of the annual rainfall12.

Sampling procedure and size determination

A cross-sectional research design was employed for this study. Data collection occurred in the Kallu district. The district was purposefully selected due to its access to information and lack of study on ICT utilization. Subsequently, two kebeles were chosen using simple random sampling. A sample size of 119 respondents was determined using simple random proportional sampling. The sample size calculation relied on a method to estimate population proportions outlined by Cochran (1977), as cited in13 as follows:

Based on the households’ variability q = 0.46 obtained from the non-users’ population number, P = 0.54 obtained from the users’ population number, and taking a 92% confidence level with ± 8% precision, hence, e = 0.08; z = 1.75. The necessary sample size is as follows:

Data type, source, collection method, and analysis

In this study, both qualitative and quantitative data were gathered. Both primary and secondary sources were used. The researcher collected the data through a household survey and focus group discussion (FGD) with 10 members. The data were analyzed by using SPSS V-25 and STATA V-17. The Pi-chart descriptive statistic was used to analyze the application of ICT tools, along the Sorghum farming life cycle, along with ANOVA and Chi-Square test, as well as content analysis for FGD findings. The inferential statistics, namely the Multinomial logit model (MNL) was used to analyze the determinants of ICT choice in sorghum crop production.

According to Wooldridge20, the specific equation for the multinomial logit model used to analyze farmers’ choice of tools (radio, mobile, TV, and Pico) could be as follows:

Where:

-

Pr (yi = k): The probability that the ith farmer chooses the kth device (radio, mobile, TV, or Pico).

-

αk: A constant term for the kth ICT device.

-

βk: A vector of regression coefficients for the kth device, representing the impact of the independent variables on the log-odds of choosing that device compared to a reference category (usually one of the ICTs).

-

xi: A vector of independent variables for the ith farmer, including factors like:

-

Socio-economic factors: Age, Gender, Farm Income, Price value, Education, and Social Influence

-

Infrastructural factor: Network Access, Electric power access

-

Perception factors: Relative Advantage, Hedonic Motivation, Compatibility, Simplicity, Quality of information, Awareness of ICTs,

-

Σ: Summation over all possible ICT devices (j = 1, 2, 3, 4).

-

This equation models the probability of each farmer (i) choosing a particular device (k) based on the combination of socio-economic and perception factors (xi).

-

The βk coefficients indicate how changes in each independent variable (e.g., age, income, network access) influence the likelihood of a farmer selecting device k compared to the reference device.

According to14 while parameter estimates provide directional information, marginal effects offer a more practical understanding of how changes in independent variables influence the likelihood of choosing different categories.

Where:

-

∂Pr(yi = k)/∂xi: Represents the marginal effect of the ith independent variable on the probability of choosing category k.

-

βk: The vector of coefficients for category k. αk: The constant term for category k.

-

xi: The vector of independent variables for the ith observation.

-

Σ: Summation over all possible categories (j = 1, 2, …, K).

Results

The application of ICTs in sorghum production

Our investigation identified the widespread application of ICTs throughout the farming life cycle (Fig. 2). The survey results revealed that most household heads (68.91%) utilized ICTs across all three stages of farming: pre-cultivation, cultivation, and post-harvest. A smaller portion (15.97%) employed ICTs in two stages, primarily pre-cultivation and cultivation. Additionally, 6.72% of respondents relied on ICTs solely during the pre-cultivation stage, while 4.2% utilized them exclusively during the combined stages of cultivation with harvesting, and 4.2% for post-harvest.

Focus group discussion (FGD) participants described they are using ICTs in various ways, including direct calling, the 8028-hotline service, and text messaging via mobile phones. Additionally, they mentioned accessing information through radio and television broadcasts, as well as attending audio-visual programs offered by Pico devices. The participants stated:

"We use direct calling, text SMS, and the 8028-hotline service by using mobile phones, and we also attend radio, TV, and Pico programs."

This participant statement shows a multi-faceted strategy for obtaining information in the farming cycle. They use both traditional as well as more contemporary forms of communication.

Mobile phone communication: Direct telephone call and text SMS are common and popular channels of interpersonal communication and getting personalized information.

8028 Hotline Service: This would suggest a single, perhaps special service for accessing a certain information or aid. The“8028”number would likely refer to a local or regional service.

Mass Media (Radio and Television): They are the traditional broadcast media, with the ability to address a massive audience with wide information and focused programs.

Pico Programs (Audio-Visual): This implies the use of Pico devices, which are usually small, portable projectors. These devices are used in an effort to distribute audio-visual content which are developed with in the native community and indigenous knowledge, perhaps for educational or informational purposes, in a communal setting.

The use of such a diverse range of methods suggests an effort to reach a wide segment of the population through channels that are both accessible and familiar to them. It also implies that different types of information or engagement might be delivered through these various platforms.

Then, we pick the points from the findings ICT application into 3 main stages of farming as follows in Fig. 3.

ICT usage within Socio-economic, infrastructural, and perception variables

The ANOVA is used to compare means across different groups. In this case (Radio, Mobile, TV, and Pico) across Age, Income, and Education. There are significant differences in age among mobile, Pico, Radio, and TV users. There are significant differences in age and income among mobile, Pico, Radio, and TV users (Table 1). Let’s see one by one:

There is a significant negative difference between the ages of those who primarily use mobile devices and those who primarily use radio. This suggests that mobile users tend to be younger. There are significant differences in age between Pico users and Mobile users, with Mobile users being younger. The result shows a significant positive difference in income between TV and radio users, suggesting that TV users have higher incomes. There is a significant difference in income between Pico and TV users, indicating that Pico users tend to have lower incomes. Although there is an overall significant difference in education, there are non-significant differences in education levels between Pico, Mobile, Radio, and TV users.

Table 2 presents the results of a Chi-Square test, which shows a significant association between categorical variables. In this case, we’re examining the relationship between various factors and the choice of ICT (Radio, Mobile, TV, Pico).

There is a significant difference between males and females in the choice of Pico, Mobile, Radio, and TV. The test reveals a significant difference between those who have and don’t have electric power access in the choice of Pico, Mobile, Radio, and TV. In addition, there is a significant difference between those who have and don’t have network access in the choice of Pico, Mobile, Radio, and TV.

There is a significant difference between those who perceived and didn’t perceive the relative advantage of technology in terms of tool choice. Additionally, there is a significant difference between those who got and didn’t get hedonic motivation from technology in the choice of Pico, Mobile, Radio, and TV. Furthermore, there is a significant difference between those who chose tools that fit with them and didn’t in the choice of Pico, Mobile, Radio, and TV. It also shows a significant difference between those who chose first info quality and didn’t in the choice of Pico, Mobile, Radio, and TV.

There is a significant association between social influence and ICT choice. There is a significant difference between those who have received peer assistance and those who haven’t in the utilization of Pico, Mobile, Radio, and TV. The test shows a significant difference between those who perceived and didn’t perceive the lower price value in the choice of Pico, Mobile, Radio, and TV.

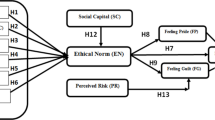

Factors determining farmers’ ICT preference

Our study investigated the factors influencing farmers’ preferences for specific Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in their agricultural practices. The dependent variable was the chosen tools class, with radio designated as the reference category for comparison with other options. This choice aligns with Martin’s19 suggestion to compare categories based on logical or significant differences, in this case, the distinct audio-only nature of radio compared to the audio-visual capabilities of other ICTs.

To ensure the model’s robustness, we assessed multicollinearity using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). All VIF values were below 10, indicating no problematic multicollinearity. Additionally, the Hausman test confirmed the validity of the Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives (IIA) assumption, signifying that the dependent variables were mutually exclusive. The model’s goodness-of-fit was further supported by a highly significant likelihood ratio test (p < 0.00) and a pseudo-R-squared value of 0.6985, suggesting that the independent variables explained approximately 69.85% of the variation in ICT preference.

While parameter estimates in the Multinomial Logit (MNL) model reveal the direction of the effect of independent variables on the dependent variable, they don’t directly represent the magnitude of change or probabilities. Therefore, marginal effects were employed to estimate the expected change in the probability of choosing a specific ICT class due to a unit change in an independent variable14. Our analysis identified 11 out of 14 hypothesized independent variables as having significant influences on ICT preference, as detailed in Table 3. The positive or negative signs of these significant variables indicate whether the likelihood of preferring a particular tool class increases or decreases relative to the reference category (radio) with a unit change in the corresponding variable.

The Multinomial Logit (MNL) analysis revealed that gender significantly influenced farmers’ decisions to choose Pico devices, with a negative effect at the 1% significance level. The marginal effect indicated an approximate 2.1% increase in the probability of female farmers choosing Pico compared to male farmers. Age emerged as another significant factor, negatively impacting the choice of mobile phones at the 1% significance level. A one-year increase in age was associated with a 5.3% decrease in the probability of utilizing mobile phones.

Education level also exerted a negative influence on the preference for Pico devices, with a statistically significant effect at the 1% level. Each additional year of formal education was associated with a 0.14% decrease in the likelihood of using Pico. Farm income emerged as a positive predictor for both mobile phone and TV utilization with a marginal effect of 0.0000154 and 5.96e-06, respectively. This means when farm income increases by one unit the probability of using Mobile increases by 0.00154% and TV by 0.000596%.

Network access played a crucial role in mobile phone usage, with a significant positive effect. The marginal effect indicated that access to a network significantly increased the likelihood of using a mobile phone by approximately 65.9%. Interestingly, electricity access positively impacted the choice of mobile phones, TV, and Pico projectors compared to Radio. This suggests that access to electricity significantly increased the probability of using mobile phones, TVs, and Pico by about 34.3%, 52.5%, and 0.06%, respectively.

Perceived relative advantage positively influenced the choice of both mobile phones and TVs. Farmers who perceived a tool as having a higher relative advantage were more likely to choose it, with marginal effects indicating a 67.9% and 0.57% increase in the probability of using mobile phones and TVs, respectively. Hedonic motivation, reflecting the desire for enjoyment and relaxation, also exerted positive effects on the selection of Mobile phones, TVs, and Pico devices. The marginal effect revealed that when farmers sought more relaxation, the probability of choosing mobile phones, TVs, and Pico devices increased by 44.6%, 15%, and 0.2%, respectively.

Compatibility perception emerged as a significant predictor of mobile phone usage. The marginal effect indicated that a positive perception of compatibility with a tool corresponded to a 78.2% increase in the likelihood of utilizing a mobile phone. Furthermore, information quality positively influenced the choice of mobile phones. Farmers seeking high-quality information were more likely to choose mobile phones, with the marginal effect suggesting a 44.3% increase in the probability of doing so. Finally, the perceived price value of a tool positively impacted the choice of Pico devices. When farmers considered the price-value proposition to be favorable, the probability of using Pico increased by approximately 0.5%.

These findigs outlined and Summarized key Marginal effects and their practical implications in Table 4 below:

Discussion

The findings of this investigation highlight the significant role of ICTs in modernizing agricultural practices. The widespread adoption of ICTs across all stages of the farming cycle underscores their potential to enhance productivity, efficiency, and sustainability in the agricultural sector. A substantial majority of household heads utilize ICTs in multiple stages of farming, demonstrating a high level of digital literacy and awareness within the farming community. The diverse range of ICT applications, including direct calling, SMS, hotline services, radio, television, and Pico devices, indicates the adaptability of ICTs to various needs and contexts. These findings align with previous research by Deloitte (2012), cited in6, which highlights the applicability of ICTs across the three key stages of the agricultural production process: pre-cultivation, crop cultivation and harvesting, and post-harvest.

The ANOVA result revealed that Mobile users tend to be significantly younger than radio and Pico users. TV users have significantly higher incomes compared to radio users. Pico users tend to have significantly lower incomes than TV users. While there’s an overall significant difference in education levels across the groups, there aren’t significant differences between specific pairs of ICT users (Pico, Mobile, Radio, and TV). The result is in line with15 younger farmers are more likely to adopt digital technologies such as mobile applications. It also consistence with16 that age and Income levels significantly influence the choice of ICT.

The Chi-Square test results reveal significant associations between several variables and ICT preference. Demographic Factors such as Sex play a significant role in ICT choice. Males and females exhibit distinct preferences for different ICTs. Access to electricity influences the choice of ICTs, likely due to the power requirements of certain devices. Network connectivity is a crucial factor, as it enables the use of data-intensive ICTs like mobile phones and smartphones. Perceived Attributes of Technology such as Individuals who perceive the relative advantage of a particular ICT are more likely to choose it. The pleasure and enjoyment derived from using an ICT can influence its adoption. The compatibility of an ICT with an individual’s lifestyle and needs is a significant determinant of choice. The perceived quality of information accessible through an ICT can impact its popularity. Social and economic Factors such as Peer influence and social norms can shape ICT preferences. Individuals who have received peer assistance are more likely to use a particular ICT. The perceived value of an ICT relative to its cost influences adoption decisions.

The MNL analysis has revealed several significant factors influencing farmers’ choices of ICTs. These fall under demographic factors, infrastructural, psychological actors/perception, and Social and economic factors.

The female farmers chose Pico compared to the male farmers. This suggests that Pico devices might be particularly beneficial for farmers lacking access to other ICT tools, potentially enabling them to receive agricultural information more effectively. Younger farmers are more likely to adopt mobile phones. Lower levels of education are associated with a higher likelihood of using Pico devices. This could be attributed to the fact that Pico programs are often presented in local languages and feature familiar local figures, making them more easily accessible to illiterate farmers compared to potentially more top-down radio programs. Higher-income is positively correlated with the use of mobile phones and TVs. Access to a network significantly increases the likelihood of using mobile phones. Electricity access positively impacts the use of mobile phones, TVs, and Pico device usage with different percentages. This finding aligns with previous research by17that the gender of the household head can influence technology adoption9. found that younger farmers are more likely to adopt and prefer modern technologies due to their familiarity and comfort with them. The result also agrees with16 that age and Income levels significantly influence the choice of ICT. In addition, with18 findings on the impact of rising income on ICT adoption by farmers. The education level enhances the ability to understand and use ICT tools effectively15.

Farmers who perceive a tool as having a higher relative advantage are more likely to choose it. The desire for enjoyment and relaxation positively influences the choice of mobile phones, TVs, and Pico devices. A positive perception of compatibility with a tool increases the likelihood of using mobile phones. Farmers seeking high-quality information are more likely to choose mobile phones. The perceived price-value proposition positively impacts the choice of Pico devices. This finding is in line with7 Perceptions of ICTs, such as relative advantage, compatibility, simplicity, and delivered information quality, which influence farmers’ choices of ICTs.

Conclusion and recommendation

Our study, surveyed 119 respondents to investigate preferences and applications of information communication technologies among farmers in Sorghum production. The findings revealed that ICTs were utilized throughout the farming cycle, encompassing pre-cultivation, cultivation, and post-harvest stages. This widespread adoption indicates the potential of ICTs to bridge information gaps for farmers across various agricultural activities. The primary ICT tools employed included radio, mobile phones, television, and Pico devices. Our analysis identified several factors influencing farmers’ preferences for specific ICTs, including gender, age, education level, farm income, network access, electricity access, perceived value, information quality, and perceptions regarding relative advantage, hedonic motivation, and compatibility. Notably, the household head’s gender and education level negatively impacted the choice of Pico devices, while factors like electricity access, hedonic motivation, and perceived value exerted a positive influence. Similarly, farm income, electricity access, relative advantage, and hedonic motivation positively affected the selection of TV, whereas age exhibited a negative influence on the preference for mobile phones. Conversely, farm income, network access, electricity access, relative advantage, hedonic motivation, compatibility, and information quality all contributed positively to the choice of mobile phones. In conclusion, our study underscores the multifaceted nature of ICT adoption in agricultural production, influenced by a combination of demographic, socio-economic, infrastructural, and perceptual factors

Based on these findings, there is a need to tailor ICT interventions to ensure that farmers can access information tailored to their specific needs and contexts (e.g. develop mobile applications that provide specific agricultural information, establish community-based ICT centers). we recommend addressing infrastructural challenges related to ICT usage, such as network connectivity and electricity access (e.g. government-subsidized Mobile devices, public–private partnerships for Network Expansion, and providing renewable energy Solutions). Expanding infrastructure is crucial to unlock the wider dissemination of ICT benefits in the agricultural sector. Additionally, considering price as a key determinant of its adoption among farmers, it is better if the government extends farmer-to-farmer knowledge sharing Platforms by using Pico, encouraging competition among telecommunication providers could lead to lower costs for consumers and encourage telecommunication providers to offer affordable data packages.

Limitations of study

The study is limited geographically, theoretical, and methodological scope. It incorporated one district and one crop, covering innovation diffusion Theory and the UTAUT 2 model. It employed a cross-section research design. So, we recommend that future research shall be conducted by using longitudinal studies, exploration of ICT utilization on other crops, and its impact on livelihood and food security. In addition, conducting in-depth impact assessments to evaluate the specific benefits and challenges associated with ICT adoption in different agricultural contexts. Furthermore, Analyzing the effectiveness of existing policies and regulations in promoting ICT adoption and use in agriculture and recommending necessary reforms.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study can be available by requesting the correspondence author.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- ICT:

-

Information communication technology

- FGD:

-

Focus group discussion

- MNL:

-

Multinomial logit

- TV:

-

Television

- UTAUT:

-

Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor

- IIA:

-

Independence of irrelevant alternatives

References

Hu, X., Gong, Y., Lai, C. & Leung, F. K. The relationship between ICT and student literacy in mathematics, reading, and science across 44 countries: A multilevel analysis. Comput. Educ. 125, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.021 (2018).

Ashraf, E., Shurjeel, H. K. & Iqbal, M. Creating awareness among farmers for the use of mobile phone cellular technology for dissemination of information regarding Aphid (Macrosiphum miscanthi, Hemiptera, Aphididae) attack on wheat crop. Sarhad J. Agric. 34(4), 724–728. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2018/34.4.724.728 (2018).

Khan, N. et al. Analyzing mobile phone usage in agricultural modernization and rural development. Int. J. Agric. Ext. 8(2), 139–147 (2020).

Mohammed, A. & Misganaw, A. Modeling future climate change impacts on sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) production with best management options in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. CABI Agric. Biosci. 3(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43170-022-00092-9 (2022).

Waqar, M. et al. ICT is an important information tool for sustainable agriculture productivity. Int. J. Biosci. (IJB). 18(2), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.12692/ijb/18.2.39-44 (2021).

Barakabitze, A. A., Fue, K. G. & Sanga, C. A. The use of participatory approaches in developing ICT-based systems for disseminating agricultural knowledge and information for farmers in developing countries: The case of Tanzania. Elec. J. Info. Syst. Dev. Countries 78(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2017.tb00576.x (2017).

Kante, M., Oboko, R. & Chepken, C. Influence of perception and quality of ICT-based agricultural input information on use of ICTs by farmers in developing countries: Case of Sikasso in Mali. Electron. J. Info. Syst. Dev. Countries 83(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2017.tb00617.x (2017).

Zegeye, F., Kirub, A. & Teshome, D. Familiarization and application of ICTs in agricultural advisory services to farmers: the case of two rural districts of Ethiopia. Et. J. Agric. Sci. 27(2), 99–109 (2017).

Kilima, F. T. M., Sife, A. S. & Sanga, C. Factors Underlying the Choice of Information and Communication Technologies among Smallholder Farmers in Tanzania. Int. J.Comput. ICT Res. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781441926133-4 (2016).

Saidu, A., Clarkson, A. M., Adamu, S. H., Mohammed, M., & Jibo, I. Application of ICT in agriculture: Opportunities and challenges in developing countries. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Mathemat. Theory, 3(1), 8–18; www.iiardpub.org (2017).

Mohammed, A., Solomon, B. W. & Ermias, T. T. Determinants of smallholders’ food security status in kalu district, northern Ethiopia. Challenges https://doi.org/10.3390/challe12020017 (2021).

Adane, A. & Asmerom, B. Analysis of spatiotemporal distribution, variability, and trends of rainfall in Wollo area Northeastern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 20(1), e0312889. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0312889 (2025).

Sarmah, H., Hazarika B. and Choudhury, G. An investigation on the effect of bias on a determination of sample size based on data related to the students of schools of Guwahati. Int. J. Appl. Mathemat. and Statist. Sci., 2, 33–48; www.researchgate.com (2013).

Greene, W. H. Econometric Analysis 4th Edition International, 201–215 (Prentice Hall, 2000).

Hoang, H. & Tran, H. Smallholder farmers’ perception and adoption of digital agricultural technologies: Empirical evidence from Vietnam. Outlook Agric. 52, 457–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/00307270231197825 (2023).

Mauti, K., Ndirangu, S. & Mwangi, S. Choice of information and communication technology tools in tomato marketing among smallholder farmers in Kirinyaga County, Kenya. J. Agric. Ext. https://doi.org/10.4314/jae.v25i3.8 (2021).

Fadeyi, O., Ariyawardana, A. & Aziz, A. Factors influencing technology adoption among smallholder farmers: a systematic review in Africa. J. Agric. Rural Dev. Tropics Subtrop. (JARTS). 123, 13–30 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Factors influencing the technology adoption behaviors of litchi farmers in China. Sustainability. 12(1), 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010271 (2020).

Martin, K.G. Strategies for choosing the reference category in dummy coding, retrieved on 24 November 2022. https://www.theanalysisfactor.com/strategies-dummy-coding/ (2020).

Wooldridge, J. M. Econometric analysis of cross-section and panel data. MIT Press.1096 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We would like to be grateful to all participants of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SAS: Acquisition, Analysis, Interpretation of data, Software, Drafted the work YSY: Conception, Design of the work, and Revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

In this research, first we got ethical approval from Bahir Dar university. Next, we got permission from the Kallu district agricultural office and selected Kebele chairman. Then, Informed consent was obtained from all participants before their involvement in the study. All research procedures were conducted according to ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seid, S.A., Yizengaw, Y.S. Preferences and applications of information communication technologies among farmers in Kallu district, Wollo, Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 22931 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05713-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05713-7