Abstract

Hearing loss (HL) is a common health issue among older adults worldwide, and its incidence is expected to increase as the population ages. A study has shown that among the estimated 500 million people with hearing impairments worldwide, 28 million Americans suffer from hearing disabilities, and the highest number of individuals with hearing impairments is found in the 45-to-64 years old age group. Depression is a significant public health concern for middle-aged and older adults. In 2015, researchers used data from over 100,000 participants that were collected by the UK Biobank to perform a cross-sectional study and reported that the association between hearing impairment and depression was more pronounced among younger participants (aged 40–49 years) and among those with milder forms of depression. These findings suggest that the impact of hearing impairment on mental health may begin to emerge in middle age. Hearing loss may lead to more obstacles for middle-aged individuals in terms of work and social interactions, thereby increasing the risk of depression. Early intervention for hearing impairment is particularly important for middle-aged people, as it can help identify early risk factors and provide more effective interventions to improve mental health and quality of life. Therefore, building on the existing literature that predominantly focused on older adults, this study involved analysing data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study(CHARLS) database, expanding the age range to 45 years, to investigate the relationship between self-reported hearing loss and depression among middle-aged and older adults. This research used data from the 2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), including data from 5207 individuals aged 45 years and older. Hearing status was self-reported by the participants, whereas depression was assessed with the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10). A multivariable logistic regression model was used to investigate the association between self-reported hearing loss and depression, controlling for sociodemographic variables that are associated with depression in middle-aged and older populations. This study involved the use of a multinomial logistic regression model to analyse the relationship between self-reported hearing loss and depression among middle-aged and older adults, with adjustments made for potential confounding variables. The analysis revealed significant relationships between depression and factors such as hearing status, sex, place of residence, self-rated health, chronic diseases, disabilities with respect to activities of daily living (ADLs), and satisfaction with life. Specifically, individuals with self-reported hearing loss, female individuals, individuals residing in rural areas, individuals with poor self-rated health, individuals with chronic diseases, and individuals with disabilities related to ADLs were more likely to experience depression. In the unadjusted model that was used to analyse the relationship between self-reported hearing loss and depression among middle-aged and older adults, both fair hearing (unadjusted OR = 1.556, 95% CI 1.377–1.758) and poor hearing (unadjusted OR = 2.001, 95% CI 1.630–2.457) were significantly associated with the prevalence of depression. After controlling for various covariates, including sex, age, residential status, education level, marital status, health status, physical disability, chronic diseases, activities of daily living (ADLs), and satisfaction with life, our study revealed that both fair hearing (adjusted OR = 1.235, 95% CI: 1.078, 1.415) and poor hearing (adjusted OR = 1.335, 95% CI: 1.063, 1.677) remained significantly correlated with the prevalence of depression among middle-aged and older adults. Previous research has focused primarily on older adults. Therefore, the present study expanded the age range to include individuals as young as 45 years old. The results show that fair hearing and poor hearing are significantly associated with the prevalence of depression among middle-aged and older adults. These findings suggest that self-reported hearing loss is a risk factor for depression in this population in China. The association between self-reported hearing loss and depression is not limited to older adults but also includes middle-aged individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hearing loss, or presbycusis, is a prevalent sensory impairment among geriatric individuals. Approximately one-third of older adults experience moderate to severe hearing impairment1,2,3,4,5,6. Hearing loss can have a significant impact on multiple aspects of the lives of older adults, including communication, cognition, emotions, and social interactions6,7. The incidence of hearing loss among middle-aged individuals is gradually increasing. Although the prevalence of hearing loss among middle-aged individuals is lower than that among older adults, hearing decline in this age group is still relatively common. The association between hearing loss and depressive symptoms has also been shown to be significant among middle-aged individuals, and interventions such as hearing aids may be more effective in this age group8. Thus, middle-aged individuals have more intervention options than older adults, which can help improve their mental health status. Currently, there are no medications available for effectively curing hearing disorders, so other interventions are needed for improvement. Auditory interventions related to hearing loss (HL) may be effective methods for preventing and treating depression. Using assistive hearing devices to improve hearing and engagement in social activities may reduce the risk of depression9.

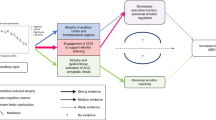

Depression is a severe psychiatric disorder that can lead to abnormal mood, insomnia, loss of interest in life, and suicidal ideation. Annually, more than one million individuals worldwide are estimated to succumb to suicide as a result of depression10,11. The number of individuals with depression has been increasing in recent years. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it is anticipated that by the year 2030, depression will become the cause of the most significant health burden worldwide12. Extensive research and discourse have been dedicated to examining the correlation between hearing loss (HL) and depression. This relationship is complex and may be influenced by multiple factors. Research has demonstrated a connection between hearing loss (HL) and cognitive deterioration, social isolation, and manifestations of depression13. These studies indicate that hearing loss (HL) may lead to reduced social activity among older adults, thereby increasing the risk of depression. Additionally, hearing loss (HL) may result in decreased activity in the brain regions that are responsible for processing sound, thereby affecting emotional regulation and cognitive function14. Nevertheless, the literature presents conflicting findings about the correlation between hearing loss (HL) and depression. While certain studies have identified a notable link between HL and depressive symptoms14,15,16others have failed to establish such a relationship17,18,19. For example, in the study by Li et al., when subjects were divided into subgroups on the basis of study type, a large effect size was demonstrated in the cross-sectional study group (g = 0.68) but not in the cohort study group (g = 0.06)20. In a study by Long Feng et al., the relationship between hearing loss and depression was found to be significant only under specific conditions, such as in middle-aged and older adult populations21. As demonstrated by Laurencese et al.22 in their meta-analysis and sensitivity analysis, there were no significant differences in depression outcomes between patients with self-reported and objectively measured hearing loss. Gopinath et al. reported that depressive symptoms were associated with mild but not moderate or severe hearing loss23 whereas Lee and colleagues reported that hearing thresholds measured with pure tone audiometry (but not self-reported hearing impairment) were associated with depressive symptomatology in a community-dwelling older Chinese population (N = 914)24. These discrepancies may be attributed to variations in research methodologies, sample sizes, participant demographics, and approaches to measuring hearing impairment25.

The relationship between hearing loss (HL) and depression is complex and potentially influenced by a variety of factors. Therefore, future research must further explore the complexity of this relationship and potential moderating factors to provide more effective preventive and intervention measures for older adults. In this study, our analysis was conducted with data from the 2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), which is a nationwide survey that collects information from participants aged 45 years and older. Because the population aged 45 years and above includes both middle-aged and older adults, this population can more comprehensively reflect the diversity of health, lifestyle, and social behaviours across different age groups. Most previous studies focused primarily on the older adults. Research on middle-aged individuals can fill this gap and provide a more comprehensive perspective on the impact of hearing impairment on mental health8.

Therefore, this demographic sample was chosen because of its representativeness and inclusivity. Our research objectives were as follows: (1) to investigate the factors influencing depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adults and (2) to assess the relationship between self-reported hearing loss and depression among individuals aged 45 years and older.

Methods

Study design and population

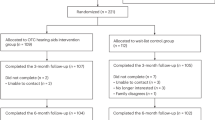

The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) is a nationally representative longitudinal survey in China targeting individuals aged 45 years and older as well as their spouses. The survey uses a random process and a multistage sampling method that is stratified by proportional probability and size. The fourth wave of the survey, which was conducted in 2018, included 19,816 adults aged 45 years and older from 150 counties/districts and 450 villages/urban communities. In this study, a total of 19,561 individuals aged 45 years and older were included. After a rigorous selection process that involved excluding respondents with missing values for key variables, excluding respondents who answered “do not know“ or refused to complete the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) questionnaire, and adjusting for data completeness, a final sample size of 5,702 was included in this study. A diagram of the study design is presented in Fig. 1.

Ethical Considerations and Compliance with Guidelines: This study utilised data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), which is a publicly available dataset that has been approved by the Peking University Biomedical Ethics Committee (Approval Number: IRB00001052-11015). All the study methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the ethical principles outlined in the “Regulations on Ethical Review of Biomedical Research Involving Human Beings”. The data that were used in this study were anonymised, and the study did not involve any direct interaction with human participants, thus ensuring the protection of participants’ privacy and confidentiality. Additionally, the use of CHARLS data complied with the guidelines for the use of harmonised datasets, which are designed to facilitate international comparative research while maintaining data integrity and ethical standards.

Depression assessment

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10), DC009-DC018, was used to evaluate the degree of depression among the study participants. The reliability and validity of the CES-D-10 scale have been verified in middle-aged and older Chinese populations26. Using eight negatively worded items and two positively worded items, the CES-D-10 scale gauges participants’ experiences over the preceding week. The items include the following: “I was bothered by trivial matters,” “I had trouble concentrating on things,” “I felt depressed,” “I felt everything I did required effort,” “I felt hopeful about the future,” “I felt fearful,” “My sleep was restless,” “I enjoyed life,” “I felt lonely,” and “I could not get going.” Participants answered the survey items by selecting one of the following responses: “Rarely or not at all (< 1 day)”, “Not very often (1–2 days)”, “Sometimes or about half the time (3–4 days)”, or “Most of the time (5–7 days)”. The four answer options are assigned scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 points, respectively. The final score was calculated by adding the scores of the ten questions. The total score ranged from 0 to 30. Respondents with scores of 10 or higher were considered to have depression, and those with scores below 10 were not considered to have depression27. Thus, based on the CES-D-10 scores, patients were categorized into two groups: “Yes” for those with depression and “No” for those without depression.

Self-reported hearing assessment

The self-reported hearing assessment uses the CHARLS questionnaire to evaluate an individual’s hearing. Participants were asked the following question: “How is your hearing? (If you frequently wear hearing aids, how is your hearing with the aids on? If you do not frequently wear hearing aids, how is your hearing without them? )” Participants selected one of the following answer choices: excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. The results were not significantly influenced by the presence of hearing aids, as only 132 participants (0.67% of the total sample) utilised hearing aids. The accuracy of the self-reported question has been validated and is considered comparable to objective measurements of hearing28. Answers of “poor” or “fair” were considered to indicate self-reported hearing difficulty28and these respondents were classified into the hearing loss group. Thus, participants who had an identified hearing impairment, who wore a hearing aid, or who had self-reported difficulty with hearing were included in the hearing loss group; the remaining participants were including in the reference group.

Evaluation of other covariates

On the basis of previous understanding, we also considered sociodemographic characteristics and health-related factors in this study. Sociodemographic covariates included age (45–59 years or ≥ 60 years), sex (male or female), place of residence (urban centre, urban–rural mixed area, rural area, or special region), marital status (married, separated, divorced, widowed, or never married), and education level (primary school or below, middle school, or high school and above). Health-related variables included self-rated health status (healthy or unhealthy), chronic disease status (no chronic disease, single chronic disease, or two or more chronic diseases), and satisfaction with life (satisfied or dissatisfied). Participants were asked about their activities of daily living (ADLs), which included the following: dressing, bathing, eating, getting in and out of bed, using the toilet, controlling urination and defecation, doing household chores, cooking, shopping, making phone calls, taking medication, and managing finances. Participants could select one of the four following answers for each activity: (1) No, I have no difficulties; (2) I have difficulties, but I can still manage; (3) Yes, I have difficulties and need help; or (4) I am unable to do it. Participants were considered to have functional disabilities if they selected any answer indicating difficulties.

Statistical analysis

The data that were utilised in this study were extracted from the DTA format of the CHARLS database, initially converted from Stata 18.0 to Excel format, and subsequently imported into SPSS 26.0 for analytical purposes. First, we outlined the data characteristics. The categorical variables are presented as n (%) and include the following: hearing condition, sex, age, place of residence, educational level, marital status, health status, physical disability, chronic diseases, activities of daily living (ADLs), and satisfaction with life. Chi-square tests were used to assess the influence of different factors on depression. For the analysis of quantitative data, t tests were used when the assumption of normality was met, whereas nonparametric tests were utilised when this assumption was not satisfied. Continuous numerical variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (\(\overline {{\text{x}}}\) ±SD) and included age and depression level. Additionally, multivariable logistic regression was used to identify the factors associated with depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults, with the outcomes presented as odds ratios (ORs) accompanied by their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A stepwise regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between self-reported hearing loss and depression. All the findings were deemed statistically significant at a significance level of p < 0.05. The variable assignments are depicted in Table 1.

Results

Study population

All the participant characteristics are presented in Table 2.

In the unadjusted model that was used to assess the relationship between self-reported hearing loss and depression, both fair hearing (unadjusted OR = 1.556, 95% CI: 1.377–1.758) and poor hearing (unadjusted OR = 2.001, 95% CI: 1.630–2.457) were significantly associated with the prevalence of depression among middle-aged and older adults (Table 3).

On the basis of the analysis presented in Model 2, after adjusting for covariates, including sex, age, place of residence, education level, and marital status, fair hearing (adjusted OR = 1.537, 95% CI: 1.355, 1.743) and poor hearing (adjusted OR = 1.990, 95% CI: 1.608, 2.462) were significantly correlated with the prevalence of depression among middle-aged and older adults (Table 4). In Model 3, after controlling for health status, physical disabilities, chronic illnesses, activities of daily living (ADLs), and satisfaction with life as covariates, our analysis revealed that fair hearing (adjusted OR = 1.235, 95% CI: 1.078, 1.415) and poor hearing (adjusted OR = 1.335, 95% CI: 1.063, 1.677) remained significantly associated with the prevalence of depression among middle-aged and older adults (Table 5).

Discussion

Most studies that examined the relationship between hearing ability and depression focused on adults aged 60 years and above, with relatively less attention given to middle-aged individuals (such as those aged 45 years and above). By extending the age range to 45 years, this study fills a gap in research on the relationship between hearing loss and depressive symptoms in this age group29. Expanding the age range increases the universality and representativeness of the study results, including a broader population and providing support for the development of more comprehensive public health policies and interventions29.

This study was based on data from the 2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). This study involved the use of a multivariate logistic regression model that was designed to analyse the association between self-reported hearing loss and depression among older adults, with adjustments made for potential confounding variables. The analysis results indicate that hearing impairment, female sex, rural residency, poor self-rated health status, chronic diseases, and limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) are associated with a greater risk of depression.

The findings of the present study indicate an association between self-reported hearing loss and depression among middle-aged and older adults. Our findings are similar to those of other studies. In the study by Wu et al.30 the methods for assessing depression and hearing loss were consistent with those used in this study. However, there were differences in sample size, age range, and covariates included compared with this study. Lu et al.31 used logistic regression to examine hearing loss as assessed via self-report, similar to the methods used in this study. However, the study population was limited to older adults. In the study by Guan et al.32 logistic regression and stepwise regression methods were used, and hearing loss was assessed via self-report in participants aged 50–80 years. In all the above studies, an association between hearing loss and depression was demonstrated.

Studies have demonstrated a correlation between hearing loss and both decreased social participation and increased risk of depression. Additionally, hearing impairment is correlated with cognitive decline and a heightened risk of dementia, which may indirectly affect the social participation and mental well-being of older adults33. Several studies suggest that the impact of hearing loss on mental health varies across different age cohorts, and a more pronounced effect is observed in younger and middle-aged populations14,17. The severity of hearing loss also affects the strength of its association with depressive symptoms. For example, a study demonstrated that for every 20-decibel increase in hearing loss, the likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms correspondingly increases15. Consequently, for older adults, undergoing routine auditory evaluations and adopting suitable intervention strategies may prove advantageous in mitigating the potential adverse effects of hearing loss on mental health.

The findings of this study demonstrate that females exhibit a greater prevalence of depression than males. A Chinese study investigating the association between adiposity and depressive symptoms revealed that 19.9% of males and 33.2% of females demonstrated depressive symptoms. Owing to hormonal fluctuations, females are more susceptible to depression34. In this study, middle-aged and older adults living in rural areas were more prone to depression. Specific socioeconomic and lifestyle factors exert a more substantial effect on depressive symptoms in rural regions. A study by Rost et al. (1998) further demonstrated the limited access to specialised treatment among older adults with depression in rural areas. This disparity potentially leads to a deficiency in effective interventions and support when addressing depressive symptoms35. Middle-aged and older adults who self-assess their health as poor are more susceptible to depression. Self-rated health is recognised as a robust predictor of long-term depressive outcomes36. This study demonstrated a significant correlation between chronic diseases and depression, and the greater the number of illnesses, the greater the risk of developing depression. A study conducted in Brazil further confirmed this perspective. Research has indicated that the prevalence of depression is markedly greater among individuals with one or more chronic diseases than among those without chronic conditions37. Furthermore, this study revealed a significant association between activities of daily living (ADLs) and depression. A prospective study involving 2,713 participants from the Chicago Chinese Older Adult Population Study also demonstrated a significant relationship between depressive symptoms and the incidence of functional impairment38. A community-based study conducted in Beijing revealed that older adults with disabilities exhibit a greater propensity for experiencing depressive symptoms39. There is a notable correlation between satisfaction with life and depression. Research that focused on older adults has identified a positive association between satisfaction with life and happiness, as well as a negative association between these psychological states and depressive symptoms. This finding suggests a potential inverse relationship between satisfaction with life and depressive symptoms, whereby an increase in satisfaction with life is associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms, and vice versa40.

This study is not without its limitations. Notably, the assessment of hearing condition was self-reported using a five-level scale rather than via standardised scales or diagnostic tools such as the older adults Hearing Impairment Survey-Screening or clinical evaluations. This methodological approach may lead to underestimation or overestimation of hearing loss severity, particularly among older adults with cognitive impairment, thereby compromising the accuracy and reliability of self-reported hearing status in this population. Therefore, when feasible, future studies should use audiometric testing to increase data reliability. However, given the complex nature of the relationship between hearing loss and depression, the analysis did not account for all potential confounding variables. Owing to the inherent characteristics of large-scale database studies, the occurrence of missing values is unavoidable. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design has inherent limitations. Future longitudinal studies or experimental designs are needed to verify potential causal mechanisms involved.

Conclusions

This research revealed a correlation between self-reported hearing loss and depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults. Furthermore, although there is an association between self-reported hearing loss and depressive symptoms, this relationship may be influenced by various confounding factors. Future research should further elucidate the causal relationship between self-reported hearing loss and depressive symptoms and investigate effective intervention strategies to improve the mental health outcomes of affected individuals. Such efforts may be pivotal for mitigating the risk of depression.

Can I obtain the CHARLS data?

All the data collected at CHARLS are maintained at the National School of Development of Peking University, Beijing, China.

Data availability

The data utilized in this research are publicly accessible. The full dataset can be requested from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HL:

-

Hearing loss

References

Agrawal, Y., Platz, E. A. & Niparko, J. K. Prevalence of hearing loss and differences by demographic characteristics among US adults: data from the National health and nutrition examination survey, 1999–2004. Arch. Intern. Med. 168 (14), 1522–1530. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.168.14.1522 (2008).

Keidser, G., Seeto, M., Rudner, M., Hygge, S. & Rönnberg, J. On the relationship between functional hearing and depression. Int. J. Audiol. 54 (10), 653–664. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2015.1046503 (2015).

Cormier, K., Brennan, C. & Sharma, A. Hearing loss and psychosocial outcomes: influences of social emotional aspects and personality. PLoS ONE. 19 (6), e0304428. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304428 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Association between activities of daily living and depressive symptoms among older adults in china: evidence from the CHARLS. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1249208. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1249208 (2023).

Chang, H. P., Ho, C. Y. & Chou, P. The factors associated with a self-perceived hearing handicap in elderly people with hearing impairment–results from a community-based study. Ear Hear. 30 (5), 576–583. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181ac127a (2009).

Lee, K. Y. Pathophysiology of age-related hearing loss (peripheral and central). Korean J. Audiol. 17 (2), 45–49. https://doi.org/10.7874/kja.2013.17.2.45 (2013).

Chang, H. P. & Chou, P. Presbycusis among older Chinese people in taipei, taiwan: a community-based study. Int. J. Audiol. 46 (12), 738–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992020701558529 (2007).

Chakrabarty, S., Mudar, R., Chen, Y. & Husain, F. T. Contribution of tinnitus and hearing loss to depression: NHANES population study. Ear Hear. 45 (3), 775–786. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001467 (2024).

Wei, J., Li, Y. & Gui, X. Association of hearing loss and risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 15, 1446262. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2024.1446262 (2024).

Bi, Y. H., Pei, J. J., Hao, C., Yao, W. & Wang, H. X. The relationship between chronic diseases and depression in middle-aged and older adults: A 4-year follow-up study from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 289, 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.032 (2021).

Ren, X. et al. Burden of depression in china, 1990–2017: findings from the global burden of disease study 2017. J. Affect. Disord. 268, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.011 (2020).

Martínez-Pérez, B., de la Torre-Díez, I. & López-Coronado, M. Mobile health applications for the most prevalent conditions by the world health organization: review and analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 15 (6), e120. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2600

Rutherford, B. R., Brewster, K., Golub, J. S., Kim, A. H. & Roose, S. P. Sensation and psychiatry: linking age-related hearing loss to late-life depression and cognitive decline. Am. J. Psychiatry. 175 (3), 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17040423 (2018).

Scinicariello, F. et al. Age and sex differences in hearing loss association with depressive symptoms: analyses of NHANES 2011–2012. Psychol. Med. 49 (6), 962–968. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718001617 (2019).

Golub, J. S. et al. Association of audiometric age-related hearing loss with depressive symptoms among Hispanic individuals. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 145 (2), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2018.3270 (2019).

Kim, H. J., Jeong, S., Roh, K. J., Oh, Y. H. & Suh, M. J. Association between hearing impairment and incident depression: A nationwide follow-up study. Laryngoscope 133 (11), 3144–3151. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.30654 (2023).

Tambs, K. Moderate effects of hearing loss on mental health and subjective well-being: results from the Nord-Trøndelag hearing loss study. Psychosom. Med. 66 (5), 776–782. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000133328.03596.fb (2004).

Fu, X., Eikelboom, R. H., Liu, B., Wang, S. & Jayakody, D. M. P. The impact of untreated hearing loss on depression, anxiety, stress, and loneliness in tonal language-speaking older adults in China. Front. Psychol. 13, 917276. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.917276 (2022).

Leverton, T. Depression in older adults: hearing loss is an important factor. BMJ 364, l160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l160 (2019).

Li, F., Jin, M., Ma, T. & Cui, C. Association between age-related hearing loss and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 20 (1), e0298495. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298495 (2025).

Feng, L. et al. Associations between age-related hearing loss, cognitive decline, and depression in Chinese centenarians and oldest-old adults. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 13, 20406223221084833. https://doi.org/10.1177/20406223221084833 (2022).

Lawrence, B. J. et al. Hearing loss and depression in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontologist 60 (3), e137–e154. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz009 (2020).

Gopinath, B. et al. Depressive symptoms in older adults with hearing impairments: the blue mountains study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 57 (7), 1306–1308. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02317.x (2009).

Lee, A. T., Tong, M. C., Yuen, K. C., Tang, P. S. & Vanhasselt, C. A. Hearing impairment and depressive symptoms in an older Chinese population. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 39 (5), 498–503 (2010).

Bowl, M. R. & Dawson, S. J. Age-related hearing loss. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Med. 9 (8), a033217. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a033217 (2019).

Fu, H., Si, L. & Guo, R. What is the optimal cut-off point of the 10-item center for epidemiologic studies depression scale for screening depression among Chinese individuals aged 45 and over? An exploration using latent profile analysis. Front. Psychiatry. 13, 820777. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.820777 (2022).

Xu, R., Liu, Y., Mu, T., Ye, Y. & Xu, C. Determining the association between different living arrangements and depressive symptoms among over-65-year-old people: the moderating role of outdoor activities. Front. Public. Health. 10, 954416. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.954416 (2022).

Ferrite, S., Santana, V. S. & Marshall, S. W. Validity of self-reported hearing loss in adults: performance of three single questions. Rev. Saude Publica. 45 (5), 824–830. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-89102011005000050 (2011).

Carrijo, M. F. et al. Relationship between depressive symptoms, social isolation, visual complaints and hearing loss in middle-aged and older adults. Psychiatriki 34 (1), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.22365/jpsych.2022.086 (2023).

Wu, C. Bidirectional association between depression and hearing loss: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. J. Appl. Gerontol. 41 (4), 971–981. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648211042370 (2022).

Lu, Z., Yu, D., Wang, L. & Fu, P. Association between depression status and hearing loss among older adults: the role of outdoor activity engagement. J. Affect. Disord. 345, 404–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.10.050 (2024).

Guan, L., Liu, Q., Chen, D., Chen, C. & Wang, Z. Hearing loss, depression, and medical service utilization among older adults: evidence from China. Public. Health. 205, 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.01.025 (2022).

Dawes, P. et al. Hearing loss and cognition: the role of hearing AIDS, social isolation and depression. PLoS ONE. 10 (3), e0119616. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119616 (2015).

Qian, J., Li, N. & Ren, X. Obesity and depressive symptoms among Chinese people aged 45 and over. Sci. Rep. 7, 45637. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45637 (2017).

Rost, K., Zhang, M., Fortney, J., Smith, J. & Smith, G. R. Rural-urban differences in depression treatment and suicidality. Med. Care. 36 (7), 1098–1107. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199807000-00015 (1998).

Ambresin, G., Chondros, P., Dowrick, C., Herrman, H. & Gunn, J. M. Self-rated health and long-term prognosis of depression. Ann. Fam Med. 12 (1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1562 (2014).

Frank, P. et al. Association between depression and physical conditions requiring hospitalization. JAMA Psychiatry. 80 (7), 690–699. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0777 (2023).

Kong, D., Solomon, P. & Dong, X. Depressive symptoms and onset of functional disability over 2 years: A prospective cohort study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 67 (S3), S538–S544. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15801 (2019).

Jiang, J., Tang, Z. & Futatsuka, M. The impact of ADL disability on depression symptoms in a community of Beijing elderly, China. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 7 (5), 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02898005 (2002).

Joshanloo, M. & Blasco-Belled, A. Reciprocal associations between depressive symptoms, life satisfaction, and Eudaimonic well-being in older adults over a 16-year period. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20 (3), 2374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032374 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study team for providing data and training in the use of the datasets. We thank Dr. Lin Zhang and Dr. Hui Yang for their rigorous instructions on this study, as well as all the participants for their efforts.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82060863), Science and Technology Projects of Guizhou Province (Qiankeheji-zk [2021] General 500), Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ethnic Medicine Science and Technology Research Special Project of Guizhou Province QZYY-2024-068, Research Project of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou University of TCM GZEYK [2020]11, and Research Project of Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine [2019]20.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XFH was responsible for data collection and collation. YBL and CHT conducted the data analysis. LZ and HY evaluated the data quality for inclusion in the study. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., He, X., Liu, Y. et al. The association between hearing loss and depression in the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Sci Rep 15, 20537 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05749-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05749-9