Abstract

Waste printed circuit boards were collected and shredded by a shredder in the current work. Shredded boards were treated by NaOH solution to remove or loosen up the polymer coating painted on the boards. As copper was the target element in this experiment two step leaching process was adopted. In the first step, low concentration HNO3 treatment was done to leach the solders and other metals except copper and second step leaching was done by H2O2 added HCl solution for copper leaching. Copper was reclaimed as nanoparticles by electrowinning using this copper-pregnant leach liquor as the electrolyte. Concentration of various elements in the leach liquors of two step leaching process was determined. Different techniques such as particle size analysis, electron microscopy, diffraction and Rietveld refinement were applied to characterize copper nanoparticles. The final copper rich solution found a concentration of copper 29,437.5 ppm with the presence of few other elements. Reclaimed copper particles were approximately 200 to 300 nm revealed by micrographs while having the average crystallite size of 76 nm determined by Rietveld refinement. The presence of metastable cuprous oxide phase was found from the diffraction analysis and the elemental copper phase percentage was 65. Microscopy also confirmed that vacuum drying of the copper particles reduced oxygen contamination from 30 to 6%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Given how much the modern world depends on electrical and electronic devices, the electronics sector is a key driver of swift technical development. To encourage the repair, reuse, and recycling of electronic gadgets, numerous nations and organizations have implemented rules. However, continuous technological advancements have led to a surge in production, consumption, and disposal, significantly increasing the volume of waste electrical and electronic equipment (E-waste). E-waste can contain up to 1,000 toxic substances, including lead, chromium, and plastic additives, posing serious environmental and health risks1. In 2016, global E-waste generation reached 44.7 million metric tons (Mt), equivalent to nearly 4,500 Eiffel Towers or 6.1 kg per inhabitant2. This number is expected to rise to 75 million metric tons by 2030, with an annual growth rate of 3–4% 3,4.

A significant amount of e-waste is made up of printed circuit boards (PCBs), which are made of a complex mixture of metals, ceramics, and polymers5,6. Waste PCBs are an economically appealing secondary metal source because of their high copper concentration (~ 20 weight%) and the presence of precious metals (~ 0.1 weight%)7. Recycling PCBs is essential for resource sustainability and environmental protection because their copper content is actually much higher than that of native Cu ores8. Copper can be recovered from waste PCBs using a variety of techniques, such as pyrometallurgy9,10,11hydrometallurgy12,13,14,15,16,17,18biotechnology19,20,21and mechanical methods22,23,24. The most popular of these are pyrometallurgical processes, which necessitate complex smelting techniques25,26. Leached PCB solutions can yield copper recovery rates of up to 98.6% 27; other methods, like supercritical CO₂ treatment, can yield recovery rates of up to 83% 28. Supercritical methanol is another documented technique that produces fine-grained copper, although it is still a costly path29. Conventional PCB recycling procedures, especially pyrometallurgical approaches27are effective, but they also present serious environmental risks. These processes can lead to the release of toxic dioxins and furans30 or generate large volumes of hazardous effluents, necessitating sustainable and eco-friendly alternatives for PCB recycling. Due to its low energy consumption, high extraction efficiency, and minimal environmental impact, the hydrometallurgical method of recovering metal from waste PCBs is becoming more and more popular. As a result, it may be scaled up and commercialized16,17,31. A wide range of lixiviants has been explored for metal leaching from PCBs, including sulfuric acid31,32aqua regia33,34and nitric acid17,35. Many of these studies, with acid concentrations ranging from 1 to 6 M, also employed H₂O₂ as an oxidizing agent, often in high concentrations (up to 30%) and under moderate temperature conditions to optimize the process16,32,36,37. However, it has been reported that Cu leach solutions derived from nitric acid are unsuitable for electrodeposition35,36,38. Despite these challenges, reclaimed copper from waste PCBs serves as an alternative to natural Cu ores, reducing the energy required for primary Cu production and benefiting the environment. This study develops a two-step hydrometallurgical process using low concentration of HNO₃ followed by HCl to selectively remove impurities and optimize Cu recovery, ensuring an ideal electrolyte composition for electrowinning while minimizing environmental impact. Since Cu nanoparticles have a high commercial value, it is crucial to generate copper in a variety of particle sizes, especially at the nanoscale, in order to further increase the value of the recovered Cu. Combining hydrometallurgy and electrometallurgy to produce Cu nanoparticles from PCBs is one promising method. This is difficult, though, because the basic material is a waste product, and producing high-quality Cu nanoparticles requires rigorous process optimization. In order to facilitate their manufacture and optimize their potential for value-added applications, this work focuses on the synthesis of Cu nanoscale particles from waste PCBs by optimizing critical parameters.

Experimental

Materials

Waste Printed Circuit Boards of Mobile Phones (A mixture of different brands) were collected from the local scrap market (Elephant Road, Dhanmondi, Dhaka). The chemical reagents (HCl, NaOH, H2O2 and HNO3) used in this study were of analytical grades (Merck, Germany and Scherlue, Spain). For all purposes, de-ionized (DI) water (pH 6.5–7.5) was used.

Instrumentation

The particle size distribution was analyzed using a laser-based particle size analyzer (Manufacturer: Microtrac, Model: S-3500, USA). Phase identification data of several synthesized products were obtained using XRD (Brand: Bruker, Model: D8 Advance, Germany). Concentration of ions in different intermediate solutions was characterized by an Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS; Brand Shimadzu, Model: AA7000, Japan). A (Brand: Jeol, Model: 71031SE2A, Japan) FESEM was used to acquire electron microscopy image and EDX analysis was done by the same instrument for the estimation of elemental contents of product samples.

Methodology

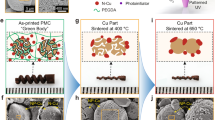

500 g of waste PCBs from mobile phones were first shredded in order to enhance surface area and decrease size. After the polymer covering was removed from the shredded material using a NaOH solution, it was exposed to an HNO₃ solution. The PCB was treated with a mixture of HCl and H₂O₂ after the HNO₃ solution was filtered away. This resulted in the extraction of Cu pregnant leach liquor for electrowinning. Cu particles were obtained by depositing copper on the cathode, collecting it by centrifugation, and vacuum-drying it. Figure 1 provides a summary of the procedure, and the Supplementary Information has additional details about the experimental work.

Results and discussion

Dismantling and shredding

Dismantling the electronic components from the PCB surface worked well since it reduced the amount of impurities in the leach liquor and helped isolate undesirable parts. With a few exceptions that required either pliers or a screwdriver, this procedure was really easy, and most parts were taken out by hand. Furthermore, disassembly made it quicker and more effective to remove the surface polymer covering while also enabling faster solvent interaction with the targeted metal areas. Shredding, as compared to dismantling alone, was found to be more efficient and adaptable. Although dismantling can precede shredding, determining the economic and industrial feasibility of this sequence requires further study. In this experiment, after multiple trials, the final process was developed using shredded PCB as the raw material, which effectively reduced particle size to 2–4 mm. This improved leachant penetration and polymeric coating removal by increasing surface area. Visual examination following NaOH treatment verified that shredding was effective in removing the covering. Additionally, shredding led to mechanical disassembly, which was more effective than manual disassembly alone because it broke down surface-mounted components while also decreasing size. Finally, by improving the contact between the PCB material and the leaching solution, shredding significantly accelerated the leaching process.

Analysis of leaching solution

The objective of this study was to recover copper nanoparticles from waste PCBs, and thus, the leaching process was specifically designed for Cu reclamation. A low-concentration nitric acid solution was initially used to dissolve solder and other unwanted elements while minimizing Cu dissolution at this stage. The subsequent leaching step, carried out with HCl and 5% H₂O₂, was exclusively focused on Cu extraction. The AAS data in Table 1, which demonstrates that the Cu concentration in the nitric acid leachate was only 102.5 ppm while it increased to approximately 30,000 ppm in the HCl solution, supports the excellent efficiency of this two-step leaching method and is consistent with the objective of optimizing Cu recovery in the final liquor.

Additionally, since Fe was not a target metal, its presence needed to be minimized in the final electrowinning solution. AAS data indicates that Fe concentration in the first step was approximately eight times higher than in the final liquor, ensuring minimal Fe interference during electrowinning. The HCl leachate had comparatively higher concentrations of Zn and Pb, although their levels would have been significantly higher in the absence of the initial nitric acid treatment. This is probably because higher molarity HCl promotes better dissolution of Zn and Pb, while low molarity HNO₃ preferentially dissolves these metals at slower rates. Cu recovery was efficiently maximized while impurity levels in the final electrowinning solution were minimized by this two-step leaching procedure.

Selectivity ratio of elements

This selectivity analysis was conducted to justify the two-step process used to obtain the final leach liquor. Since Cu was the target element, all other metals, including Zn, Fe, and Pb, were regarded as impurities for the electrowinning stage. These elements can interfere with Cu during electrowinning by competing for deposition sites, altering morphology, and reducing purity. To minimize their effects, pre-treatment with 0.3 M HNO₃ was used to reduce impurity concentrations, followed by HCl leaching in the second stage to obtain the final leach liquor for electrowinning. Selective precipitation and filtration could further enhance impurity removal, but in this study, purification was intentionally omitted to evaluate the feasibility of Cu electrowinning under real conditions. Given that low overpotential control promotes preferential Cu deposition, impurity incorporation was expected to be minimal39. Ayorinde et al.40 suggested a minimum standard selectivity ratio of 5 for an effective lixiviant, based on studies using six different lixiviants, including HCl and HNO₃ at various molarities.

The efficiency of the chosen hydrometallurgical process was demonstrated in this investigation by the selectivity ratios for Cu relative to Fe and Pb, which were 63 and 110, respectively (Fig. 2). Despite being lower, the Zn selectivity ratio was still three times more than the typical threshold suggested by Ajiboye et al.40. These results demonstrate that the chosen procedure successfully reduces impurity concentration, ensuring a good recovery of copper in the final leach liquor.

Recovery of copper element

Copper recovery from the hydrochloric acid leach liquor was optimized through multiple trial-and-error experiments using a digital DC voltage source. The final electrowinning process was conducted on a 100 mL solution (pH 1.3) using graphite electrodes at 5 V for 5 min. The formation of Cu particles was driven by controlled nucleation and restricted growth, influenced by temperature and stirring. In the final optimized process, electrowinning was performed at 65 °C with a 750 rpm magnetic stirrer, which significantly reduced particle size. In contrast, because of unrestricted growth, electrowinning without heating and stirring produced larger, micron-sized Cu particles. The improved electrode kinetics and increased ion mobility at 65 °C, enhanced the nucleation rate and inhibited large aggregates formation. Stirring at 750 rpm further contributed to uniform ion distribution, minimized growth, and promoted the formation of smaller, well-dispersed Cu particles. A higher current density of 20 mA/cm² under temperature and stirring conditions, as compared to 12 mA/cm² without these effects, further confirmed this. These optimized conditions shifted the electrowinning balance away from bulk metal deposition, demonstrating a viable approach for Cu nanoparticle synthesis through electrochemical methods41. After 5 min of electrowinning, the electrodes became fully covered with Cu particles. To maximize recovery, the process was repeated multiple times in the same electrolyte, achieving a 77% yield.

Particle size analysis

Particle size analysis was conducted for two samples: Sample-1 (electrowinning without temperature and stirring) and Sample-2 (electrowinning with temperature and stirring). Sample-1 exhibited a broad and random particle size distribution, as shown in Fig. 3a, with two distinct peaks. The first peak, which was centered at 336 nm varied between 200 and 500 nm, while the second peak indicated an average particle size of 1205 nm. Figure 3a shows that 75% of the particles in Sample-1 were in the micron size, indicating that larger particles predominated.

To achieve a narrower size distribution and smaller particles, electrowinning was performed under temperature and stirring conditions (Sample-2). Figure 3b shows a single sharp peak, indicating a uniform distribution, with particle sizes ranging from ~ 200 nm to 300 nm and an average size of 270 nm. This improvement is attributed to increased ion mobility at higher temperatures, which promoted nucleation over growth. Moreover, stirring further stabilized the formation of smaller particles. These findings demonstrate that temperature and stirring play a crucial role in controlling particle size during electrowinning.

SEM imaging and EDX analysis

SEM analysis further confirms the significant role of stirring and temperature in controlling particle size during electrowinning. Figure 4a (Sample-1) shows broad particle size distribution (~ 500 nm) with noticeable agglomeration, while the three-dimensional morphology reveals a mix of circular, cuboidal, rectangular, and round-shaped particles, indicating uncontrolled growth. In contrast, Fig. 4b (Sample-2) exhibits more uniform particle sizes (200–300 nm) with a distinct “sliced fruit” shape, which is probably caused by the electrolyte’s circular movement under constant magnetic stirring. Unlike Sample-1, Sample-2 shows no significant agglomeration, indicating better dispersion and stability.

The reduction in particle size is attributed to the synergistic effect of increased current density and enhanced nucleation rate at higher temperatures. At elevated solution temperature, current density increases, promoting higher nucleation site formation and smaller grain sizes42,43. Furthermore, stirring prevents excessive growth at a single nucleation site, ensuring uniform ion deposition across multiple sites. This combined effect of temperature and stirring facilitates the formation of finer, well-dispersed, and homogeneous Cu particles during electrowinning.

EDX analysis was conducted on a macro scale, providing an overall compositional overview rather than data from a specific particle. Some unidentified peaks in the spectra were attributed to instrumental artifacts, such as carbon (C) from the carbon tape and platinum (Pt) from the sputtering process performed prior to SEM analysis.

Table 2 exhibits a compositional summary of the EDX analysis. Figure 5; Table 2 confirm the presence of Cl in Sample-1, indicating incomplete rinsing with deionized (DI) water. This problem was resolved in Sample-2, where Cl contamination was successfully eliminated by extensive DI water rinsing.

Another notable observation was the high oxygen (O) content in Sample-1, likely due to air drying, which promoted oxidation. The oxygen content of Sample-2 dropped by around 24% after vacuum drying, indicating that oxidation was successfully reduced under controlled drying conditions. However, open-air handling or air exposure during storage may be the cause of the trace oxygen found in Sample-2. Regarding Cu content, Sample-2 contained 87% Cu, which would exceed 90% if C artifacts were excluded, whereas Sample-1 contained only 50% Cu. This highlights how crucial appropriate cleaning, drying, and storing are to producing high-purity Cu particles.

XRD analysis

XRD analysis of Sample-1 (Fig. 6a) confirmed the presence of metastable cuprous oxide (Cu₂O) (JCPDS: 01-071-3645), indicating that the initially synthesized product was elemental Cu, which later oxidized. SEM-EDX analysis revealed that 30% oxygen content contributed to Cu₂O formation, likely due to air exposure during storage or handling prior to SEM and XRD analysis. Additionally, the initial hump in the XRD scan suggests moisture absorption, possibly resulting from the air-drying process or environmental contamination at a later stage.

In contrast, XRD analysis of Sample-2 (Fig. 6b) predominantly detected elemental Cu (JCPDS: 00-004-0836) with a minor presence of Cu₂O. The higher peak intensity in the XRD pattern indicates a high degree of crystallinity, suggesting the presence of single-crystal domains or very small grains. The formation of metastable Cu₂O in Sample-2 can be attributed to the high reactivity of Cu nanoparticles, as their smaller size increases surface area and susceptibility to oxidation. Unlike Sample-1, peak broadening (higher FWHM) in Sample-2 suggests that vacuum drying helped stabilize the copper phase by limiting oxidation. Notably, air-dried samples (Sample-1) did not exhibit detectable elemental Cu, while vacuum-dried Sample-2 predominantly retained metallic Cu, highlighting the importance of controlled drying conditions in preserving nanoparticle stability.

Rietveld refinement

Rietveld refinement of samples provided the crystallite parameters of both Sample-1 and Sample-2.

The Rietveld refinement process successfully matched all diffraction peaks for both phases, except for the final peak of the copper phase (Fig. 7d), which exhibited partial matching. This discrepancy may be due to the presence of a twin phase, contributing to a minor deviation. As shown in Fig. 7a, after instrumental calibration, all peaks remained intact for further phase identification and analysis. Figure 7b confirms that Sample-1 consists entirely of the cuprite phase (Cu₂O) with 100% purity. In contrast, the refinement analysis of Sample-2 initially detected Cu₂O (Fig. 7c) and then identified elemental copper (Cu) (Fig. 7d), revealing a composition of 65% copper and 35% cuprite. Following the refinement process, the residual error in both graphs was significantly reduced, resulting in nearly straight residual lines, indicating a high degree of accuracy in the Rietveld refinement. The crystallite parameters derived from this analysis, as summarized in Table 3, further confirm that Sample-2 contains 65% copper and 35% cuprite, whereas Sample-1 is entirely composed of the cuprite (Cu₂O) phase.

The crystallite size of the copper phase in Sample-2 was determined to be 76.7 nm. Additionally, the cuprite (Cu₂O) phase exhibited a reduction in crystallite size, decreasing from 55.8 nm in Sample-1 to 41.5 nm in Sample-2. This reduction is likely a result of the heat and stirring conditions applied in the electrolytic cell, which influenced the phase formation process. Furthermore, this trend suggests that smaller crystallites are more susceptible to oxidation, leading to the formation of the metastable cuprite (Cu₂O) phase. The Rietveld refinement analysis confirmed that both phases belong to a cubic crystal structure, with lattice parameters of 3.62 Å for the copper phase and 4.27 Å for the cuprite phase. A slight increase in the crystal density of Cu₂O by 0.007 g/cm³ in Sample-2 indicates a possible reduction in porosity. Additionally, the crystal density of the copper phase in Sample-2 closely approached its theoretical density of 8.96 g/cm³, further supporting the phase stability and material integrity.

Comparison with literature data

Table 4 compares the achieved results found in studied literature with this work.

Considering the leaching parameters, having 10 times higher solid to liquid (S/L) ratio and without temperature application, concentration of Cu in the leach liquor has been found approximately 1.5 times rich compared to Yang et al. For Cu recovery when solvent extraction process was adopted use of modifier was necessary which made the process complex since handling of additional chemical became mandatory. Moreover, this route found the particles in the micrometer (µm) range not even in the nano range. In the super critical methanol process, higher temperature condition compared to this study was adopted which found the particles in a range of 100–500 nm without further purification of leach solution. On the other hand, purified leach solution was able to synthesize particles of 50–300 nm while this study found the average particles size in 270 nm without purification. It could be mentioned that purification of leach liquor is laborious, chemically more complex, time consuming and economically unpractical. Another point to mention about the current study is that it uses the most efficient leaching process and a simple metal recovery technology to reduce process complexity and potential operational costs.

Conclusions

The increasing use of electronic devices has led to a global environmental challenge associated with electronic waste (E-waste), necessitating the development of sustainable recovery methods. This study focused on the recovery of copper from waste printed circuit boards (WPCBs), transforming it into a value-added product in the form of Cu nanoparticles. A combination of physical and chemical treatments, followed by a two-step leaching process, successfully prepared a Cu-rich solution with a concentration of 29,437.5 ppm, which was then used as an electrolyte for electrowinning. Under optimized conditions (65 °C, 750 rpm stirring), Cu nanoparticles were reclaimed, with sizes ranging from 200 nm to 300 nm and an average crystallite size of 76 nm. The measured density of 8.894 g/cm³ closely matched the theoretical Cu density of 8.96 g/cm³, indicating high purity. This study demonstrates that Cu nanoparticles can be directly recovered from PCB leach liquor using electrometallurgy without additional purification steps, making the process efficient and cost-effective. The results further confirm that elevated temperature and stirring play a crucial role in reducing particle size and ensuring uniform morphology. However, Cu nanoparticles exhibit a tendency toward oxidation, primarily forming the metastable cuprous oxide (Cu₂O) phase, which can be minimized through vacuum drying and careful storage. This approach offers a simple, scalable, and environmentally sustainable method for Cu recovery, contributing to the circular economy and reducing dependence on primary Cu extraction. In order to ensure compliance with environmental requirements and promote sustainable metal recovery, waste solutions from leaching and electrowinning should be neutralized, precipitated to remove heavy metals, and then safely disposed of or recycled.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

E-Waste Management | International Environmental Technology Centre. https://www.unep.org/ietc/what-we-do/e-waste-management

Balde, C. P., Forti, V., Gray, V., Kuehr, R. & Stegmann, P. The Global E-Waste Monitor 2017. United Nations University (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proci.2014.05.148

Barthet, A., Chauris, H., Romary, T., Semetey, V. & Chautru, E. Advanced granulometric characterization of shredded waste printed circuit boards for sampling. Waste Manage. 187, 296–305 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Enhanced recovery of high purity Cu powder from reclaimed copper smelting fly Ash by NH3·H2O–NH4Cl slurry electrolysis system. J. Clean. Prod. 428, 139368 (2023).

Cayumil, R. et al. High temperature investigations on optimising the recovery of copper from waste printed circuit boards. Waste Manage. 73, 556–565 (2018).

Islam, M. K., Haque, N. & Somerville, M. A. Characterisation and Techno-Economics of a Process to Recover Value from E-waste Materials BT - TMS 2021 150th Annual Meeting & Exhibition Supplemental Proceedings. in 995–1006Springer International Publishing, Cham, (2021).

Kiddee, P., Naidu, R. & Wong, M. H. Electronic waste management approaches: An overview. Waste Manage. 33, 1237–1250 (2013).

Syed, S. Recovery of gold from secondary sources—A review. Hydrometallurgy 115–116, 30–51 (2012).

Jung, M., Yoo, K. & Alorro, R. D. Dismantling of electric and electronic components from waste printed circuit boards by hydrochloric acid leaching with Stannic ions. Mater. Trans. 58, 1076–1080 (2017).

Cayumil, R. et al. Generation of copper rich metallic phases from waste printed circuit boards. Waste Manage. 34, 1783–1792 (2014).

Flandinet, L., Tedjar, F., Ghetta, V. & Fouletier, J. Metals recovering from waste printed circuit boards (WPCBs) using molten salts. J. Hazard. Mater. 213–214, 485–490 (2012).

Li, H., Eksteen, J. & Oraby, E. Hydrometallurgical recovery of metals from waste printed circuit boards (WPCBs): Current status and perspectives – A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 139, 122–139 (2018).

Birloaga, I., Coman, V., Kopacek, B. & Vegliò, F. An advanced study on the hydrometallurgical processing of waste computer printed circuit boards to extract their valuable content of metals. Waste Manage. 34, 2581–2586 (2014).

Fogarasi, S., Imre-Lucaci, F., Egedy, A., Imre-Lucaci, Á. & Ilea, P. Eco-friendly copper recovery process from waste printed circuit boards using Fe3+/Fe2 + redox system. Waste Manage. 40, 136–143 (2015).

Tuncuk, A., Stazi, V., Akcil, A., Yazici, E. Y. & Deveci, H. Aqueous metal recovery techniques from e-scrap: hydrometallurgy in recycling. Min. Eng. 25, 28–37 (2012).

Wojtal, T., Saternus, M., Willner, J., Rzelewska-piekut, M. & Lisi, M. Two-Stage leaching of PCBs using sulfuric and nitric acid with the addition of hydrogen peroxide and Ozone. (2024).

Kumari, S., Panda, R., Prasad, R. & Alorro, R. D. Sustainable process to recover metals from waste PCBs using physical Pre-Treatment and hydrometallurgical techniques. 1–17 (2024).

Oke, E. A. & Potgieter, H. Recent chemical methods for metals recovery from printed circuit boards: A review. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 26, 1349–1368 (2024).

Rodrigues, M. L. M. et al. Copper extraction from coarsely ground printed circuit boards using moderate thermophilic bacteria in a rotating-drum reactor. Waste Manage. 41, 148–158 (2015).

Wu, W., Liu, X., Zhang, X., Zhu, M. & Tan, W. Bioleaching of copper from waste printed circuit boards by bacteria-free cultural supernatant of iron–sulfur-oxidizing bacteria. Bioresour Bioprocess. 5, 10 (2018).

Zhu, N. et al. Bioleaching of metal concentrates of waste printed circuit boards by mixed culture of acidophilic bacteria. J. Hazard. Mater. 192, 614–661 (2011).

Nekouei, R. K., Pahlevani, F., Rajarao, R., Golmohammadzadeh, R. & Sahajwalla, V. Two-step pre-processing enrichment of waste printed circuit boards: mechanical milling and physical separation. J. Clean. Prod. 184, 1113–1124 (2018).

Guo, C., Wang, H., Liang, W., Fu, J. & Yi, X. Liberation characteristic and physical separation of printed circuit board (PCB). Waste Manage. 31, 2161–2166 (2011).

Duan, H., Hou, K., Li, J. & Zhu, X. Examining the technology acceptance for dismantling of waste printed circuit boards in light of recycling and environmental concerns. J. Environ. Manage. 92, 392–399 (2011).

Islam, M. K. et al. Effect of B2O3 on the Liquidus temperature and phase equilibria in the CaO–Al2O3–SiO2–B2O3 slag system, relevant to the smelting of E-waste. J. Sustainable Metall. 8, 1590–1605 (2022).

Islam, M. K. et al. Phase equilibria study of CaO-Al$_{2}$O$_{3}$-SiO$_{2}$-Na$_{2}$O slags for smelting waste printed circuit boards. JOM - J. Minerals Met. Mater. Soc. 73, 1889–1898 (2021).

Veit, H. M., Bernardes, A. M., Ferreira, J. Z., Tenório, J. A. S. & de Malfatti, C. Recovery of copper from printed circuit boards scraps by mechanical processing and electrometallurgy. J. Hazard. Mater. 137, 1704–1709 (2006).

Calgaro, C. O. et al. Fast copper extraction from printed circuit boards using supercritical carbon dioxide. Waste Manage. 45, 289–297 (2015).

Xiu, F. R. et al. A novel recovery method of copper from waste printed circuit boards by supercritical methanol process: Preparation of ultrafine copper materials. Waste Manage. 60, 643–651 (2017).

Menad, N., Björkman, B. & Allain, E. G. Combustion of plastics contained in electric and electronic scrap. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 24, 65–85 (1998).

Wstawski, S., Emmons-Burzyńska, M., Rzelewska-Piekut, M., Skrzypczak, A. & Regel-Rosocka, M. Studies on copper(II) leaching from e-waste with hydrogen sulfate ionic liquids: Effect of hydrogen peroxide. Hydrometallurgy 205, 105730 (2021).

Ippolito, N. M., Medici, F., Pietrelli, L. & Piga, L. Effect of acid leaching Pre-Treatment on gold extraction from printed circuit boards of spent mobile phones. Mater. 2021. 14, 362 (2021).

Bas, A. D., Deveci, H. & Yazici, E. Y. Treatment of manufacturing scrap TV boards by nitric acid leaching. Sep. Purif. Technol. 130, 151–159 (2014).

Kumar, M., Lee, J. C., Kim, M. S., Jeong, J. & Yoo, K. Environ. Eng. Manage. 13, 2601–2607 (2014).

Gande, V. V., Vats, S., Bhatt, N. & Pushpavanam, S. Sequential recovery of metals from waste printed circuit boards using a zero-discharge hydrometallurgical process. Clean. Eng. Technol. 4, 100143 (2021).

Kumari, S., Panda, R., Prasad, R., Alorro, R. D. & Jha, M. K. Sustainable process to recover metals from waste PCBs using physical Pre-Treatment and hydrometallurgical techniques. Sustainability (Switzerland) 16, (2024).

Behnamfard, A., Salarirad, M. M. & Veglio, F. Process development for recovery of copper and precious metals from waste printed circuit boards with emphasize on palladium and gold leaching and precipitation. Waste Manage. 33, 2354–2363 (2013).

Hsu, E., Barmak, K., West, A. C. & Park, A. H. A. Advancements in the treatment and processing of electronic waste with sustainability: a review of metal extraction and recovery technologies. Green Chem. 21, 919–936 (2019).

Elsherief, A. E. Effects of Cobalt, temperature and certain impurities upon Cobalt electrowinning from sulfate solutions. 43–49 (2003).

Ajiboye, A. E. et al. Extraction of copper and zinc from waste printed circuit boards. Recycling 4, 1–13 (2019).

Hashemipour, H., Zadeh, M. E. & Pourakbari, R. Investigation on synthesis and size control of copper nanoparticle via electrochemical and chemical reduction method. 6, 4331–4336 (2011).

Lai, J. The effect of temperature on limiting current density and mass transfer in electrodialysis. 123–132 (1987).

Popov, K. I. & Djokić, S. S. B. N. G. Fundamental Aspects of Electrometallurgy (Kluwer Academic/Plenum, 2002).

Yang, J., Wu, Y. & Li, J. Hydrometallurgy recovery of ultra Fi Ne copper particles from metal components of waste printed circuit boards ☆. Hydrometallurgy 121–124, 1–6 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology. The authors are grateful to the Bangladesh Council of Scientific and Industrial Research for allowing them to use their labs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAR: Experimental Conduct; Analysis; Write-upHMMAR: Concept; Review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M.A.R., Rashed, H.M.M.A. Selective recovery of nanoscale copper particles from mobile phone waste printed circuit boards through acid leaching and low temperature electrowinning. Sci Rep 15, 23195 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05862-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05862-9