Abstract

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is an effective method to treat swine manure and recover energy. However, swine manure with high total solid concentration often leads to long startup time of anaerobic digesters, low degradation efficiency of organic matter and incomplete fermentation. Herein, the hydrothermal hydrolysates of digestate obtained at two centrifugal speeds (i.e., the supernatant derived from 4000 to 10,000 rpm, respectively, named H4000 and H1000) co-digested with swine manure were conducted to investigate the effects of hydrolysate addition on AD startup and performance. Although the concentrations of organics were a slightly higher in H4000 than in H10000, a rapider biogas production occurred in the co-digestion of the H10000 hydrolysate and swine manure, indicating that the finer hydrochar was more optimal to prompt AD startup and performance than larger hydrochar. The fine hydrochar in the hydrolysate had a higher charge storage capability, and lower electron-transfer resistance, which could enhance the direct interspecies electron transfer between bacteria and methanogens and microbial activity. Also, hydrolysate addition could promote the growth of potential exoelectrogenic bacteria in AD. These findings provide a deep understanding of the effects of hydrolysate on the AD systems and are helpful for developing AD techniques for swine manure treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is an effective method to treat swine manure and recover energy in the form of biogas (i.e., methane)1. Methane generation in AD is carried out by a series of microorganisms including hydrolytic and fermentative bacteria, acetogenic bacteria and methanogens2,3. During AD, swine manure with high total solid (TS) concentration often leads to volatile fatty acid (VFA) accumulation and pH decrease due to the growing imbalance of hydrolytic and fermentative bacteria and methanogens, which result in long startup time of anaerobic digesters, low degradation efficiency of organic matter and incomplete fermentation4,5. Therefore, improving the conversion of organic matter in swine manure and shortening the startup time of anaerobic digester are necessary for engineering applications.

Hydrothermal treatment (HT) has been employed to treat organic matter for producing hydrochar, bio-oil/chemicals, aqueous phase and gas6,7. HT is generally carried out in a mild temperature range of 120–250 °C with water functioning as the reaction media8. HT of organic matter can produce a large amount of hydrothermal hydrolysate, which contains high concentrations of proteins, organic acids, phenols, benzene, saccharides and nitrogen compounds9. A combined process of hydrothermal hydrolysate and AD has been widely studied and used for solid organic matter treatment such as sludge and agricultural straw, owing to non-fossil resource heat needed for HT, especially, this treatment becomes attractive if proximity to a power plant is provided10. Wang et al.11 reported that the co-digestion of corn stover and its hydrothermal hydrolysate could increase 5.8–10.7% of methane production compared with the mono-digestion of corn stover or its hydrothermal hydrolysate. Zhao et al.12 found the hydrothermal hydrolysate of wheat straw obtained at 120 °C co-digested together with the solid residual could increase 21.5% of the methane yield. So far, the addition of hydrothermal hydrolysate has been proven to be a promising approach for solid organic waste valorization and potential carbon emission reduction.

The degradation of soluble organics in the hydrolysate has been considered to be mainly responsible for the enhancement of biogas (methane) production. Except for the organics, there are abundant suspended particles (i.e., fine hydrochar) in the hydrothermal hydrolysate. Hydrochar is one of organic waste hydrothermal products, which is rich in various functional groups such as –OH and –COOH and has a good pore structure13. Hydrochar can work as the carrier to support methanogens, leading to a more stable activity under high load conditions and less lag time of AD. Additionally, the porous frame structure of hydrochar can act as a good electronic conductor, enhance the electron transfer between bacteria and methanogens in AD systems, and improve AD performance14,15. Moreover, the hydrochar addition in AD system is beneficial to the removal of toxic contaminants (e.g., nanoplastics and phenol) through capture or bio-degradation and mitigating the inhibitory effect of toxic contaminants on methane production16. However, the effects of hydrolysate components including organics and fine particles on AD startup and performance has been rarely known.

The aim of this study was to explore the effects of organics and fine particles in the hydrolysates on AD startup and performance of swine manure. Two hydrolysates of swine manure digestate obtained at different centrifugal speeds (i.e., the supernatant derived from 4000 and 10,000 rpm) were used to conduct the AD experiment. The physio-chemical characteristics, electron transfer capacity, and conductivity of the hydrolysate particles and hydrothermal residue (HR, i.e., centrifugal precipitate) were characterized. During the AD operation, the biogas and methane yield, and the degradation of organics were detected. The shift of microbial community and exoelectrogenic bacteria in different hydrolysate treatments was analyzed by applying MiSeq sequencing. The obtained results could provide a deep understanding of the effects of hydrolysate on the AD systems and was helpful for developing AD techniques for swine manure treatment.

Materials and methods

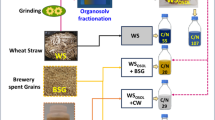

HT process and material preparation

Swine manure digestate was taken from swine farms in Quzhou City, Zhejiang Province, China, as described by Sun et al.17. The TS and volatile solid (VS, on TS basis) concentrations of the dewatered digestate were 24.75 ± 2.31% and 64.82 ± 3.27%, respectively. HT was applied to pretreat the swine manure digestate to obtain hydrolysate. The swine manure digestate was adjusted to the TS content of 10% with tap water and then put into a hydrothermal device, which consisted of a hydrothermal tank with an effective volume of 4 L and a flash tank with an effective volume of 8 L18. The hydrothermal device was purged with high-purity N2 (99.99%) at a flow rate of 400 mL min−1 to create an oxygen-free environment. The mixture was heated to 180 °C at a heating rate of 3 °C min−1 and kept at 180 °C for 35 min. Then, the electric valve was opened to burst the hydrothermal slurry into the flash tank. The hydrothermal slurry was centrifuged at 4000 (i.e. 1431 × g) or 10,000 rpm (i.e. 8944 × g) for 20 min to obtain hydrolysate, labeled H4000 and H10000, respectively. The centrifugal precipitate at 4000 rpm was dried in an oven at 65 °C and was denoted as HR.

AD experiment with hydrothermal products

In order to illustrate the effects of hydrothermal hydrolysate components including organics and fine particles on AD startup and performance, six AD treatments were conducted in the batch experiment: (1) the traditional swine manure AD (control), labeled as CK; (2) the co-digestion of swine manure and H4000 hydrolysate, labeled as CL1; (3) the co-digestion of swine manure and H10000 hydrolysate (the particle concentration in the H10000 hydrolysate was adjusted to the same as in the H4000 hydrolysate with the particles, which was obtained from the H10000 hydrolysate by drying at 60 °C), labeled as CL2; (4) the mono-digestion of the H4000 hydrolysate, labeled as CL3; (5) the co-digestion of swine manure, H4000 hydrolysate and HR, labeled as CLS; and (6) AD only with the inoculum as the blank group, labeled as NT (Table S1). Each treatment was conducted in triplicate.

AD reactor was composed of a 1 L glass bottle with an 800 mL working volume. After being purged with high-purity N2 (99.99%) at a flow rate of 50 mL min−1 for 10 min, the AD reactor was sealed with a rubber stopper, and wrapped with black plastic to avoid light as described by Kang et al.19. The swine manure was taken from swine farms in Quzhou City, Zhejiang Province, China17. To ensure the experimental materials of swine manure were relatively uniform, the swine manure was first air-dried, ground and screened through a 10-mesh sieve, and then added into the AD reactors with the TS content of ~ 12% for AD. Although the physiochemical and biological properties of air-dried swine manure might vary a little, it could be well used to construct the same mass of manure substrate for the experiment treatments to eliminate the operation error owing to the settlement of manure slurry. The inoculum collected from lab-scale swine manure AD digesters was added to accelerate AD, with the TS and VS concentrations of 29.7 and 23.2 g L−1, respectively. A low inoculum of 10% (v/v) was used to investigate the effects of the components of hydrolysate on the AD startup and performance in this study. AD experiments were conducted in a 38 °C-water bath at 80 rpm for 100 d. The biogas and methane production in the AD reactors were calculated by the blank control (NT treatment) subtracted from those in the corresponding treatments and expressed in the unit of mL gTS−1.

Characterization of the hydrothermal products

To investigate the electron transfer properties of HR and the fine particles in the hydrolysate (i.e., H4000 and H10000 particles), the HR and hydrolysate were dried in an oven at 60 °C, respectively. The surface morphology and elemental compositions of the dried HR and the fine particles of H4000 and H10000 were analyzed by a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, FEI Quanta 450, 20 kV, USA) equipped with an energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS). The fourier transform infra-red (FTIR, Nicolet iS10, Thermo Fisher, USA) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCALAB, 250Xi, Thermo Scientific, USA) were used to analyze the functional groups and elemental structures of the hydrothermal products. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) of HR and fine particles were analyzed by an electrochemical workstation CHI660E (Shanghai Chenhua, China). The working electrodes were prepared by the dropcast method20. Briefly, the prepared fine particles or HR samples (0.8 g) were mixed with conductive carbon black and polytetrafluoroethylene water lotion (60 wt%) in a mass ratio of 8:1:1 in 10 mL ethanol. The mixture was ultrasonicated for 30 min to make it completely dispersed, and then heated in a water bath to form a sample paste. The paste was brushed on 1 × 1 cm stainless steel foam (the effective surface area was 2 cm2), and dried in vacuum under 60°C. The fine particles or HR sample loading rate was ~ 25 mg on each working electrode. In the three-electrode test system, stainless steel and Hg/HgO reference electrode (SEC) were applied as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively, and the fine particles- or HR-modified electrodes were working electrodes. The electrolyte was Na2SO4 solution (0.5 mol L−1). The voltage of the CV test was set from − 0.1 to 1.1 V. The EIS tests were performed at an open-circuit voltage in the frequency range of 10‒2–105 Hz and the amplitude of 5 mV.

Analytical methods

During the AD experiment, biogas samples were collected to measure the concentrations of CH4 and CO2 by a gas chromatograph with a thermal conductivity detector (GC-TCD) as described by Wang et al.21. Approximately 20 mL AD samples were taken from the anaerobic reactors periodically for physicochemical characteristics. The concentrations of TS and VS were determined by drying a certain volume of digestion at 105 °C until constant weight, and igniting at 600 °C for 3 h, respectively. The remaining samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 20 min to obtain the solid and liquid samples. The concentrations of chemical oxygen demand (COD), NH4+-N, TN and pH value were measured as the methods described by Eaton et al.22. The concentrations of soluble protein and soluble sugar were determined by modified Lowry’s method and phenol sulfuric acid method, respectively23. The concentration of VFAs was analyzed by a gas chromatograph with a flame ionization detector (GC-FID) as described previously24. The contents of protein and total sugar in the solid samples were determined by the Kjeldahl determination and phenol–sulfuric acid method, respectively25,26. The contents of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin in the solid samples were determined by Van Soest method27.

The conductivity of hydrolysate, tap water, and the initial mixture of CK (tap water + swine manure), CL1 (tap water + H4000 + swine manure), CL2 (tap water + H10000 + swine manure), and CLS (tap water + H4000 + swine manure + HR), was measured with DDS-307A conductivity meter (Thundermagnetic, China). The size distribution of the particles in the H4000 and H10000 hydrolysates was determined using the QICPIC system (Sympatec, GmbH, Germany)28. The morphology of the solids was observed using a Philips XL-30E scanning electron microscope (Holland). Each sample was measured in triplicate.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and MiSeq sequencing

The AD samples were collected from the AD reactors on days 1, 13, 34, 62, and 100, and used to analyze the succession of microbial community structure. Genomic DNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A.™ soil DNA extraction kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Inc., Norcross, USA). PCR amplification was performed for the V3-V4 region of total bacterial DNA using the primer set 338F/806R with barcodes29. The PCR products were sequenced on Illumina Miseq platform at Shanghai Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. The sequencing data were analyzed as described by He et al.30.

Data analysis

In the three-electrode system, the specific capacitance (Cp, F g−1) was calculated using Eq. (1)31.

where i is the response current density inside the CV curve, A; Vi and Vf are the initial and final scan voltages, respectively, mV; m is the mass of active material, g; k is the scan rate, mV s−1.

The statistical analysis of data was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS 19.0. Canonical correlation analysis (CCA) for the correlation between the environmental parameters and the microbial community in the AD reactors was performed using the Vegan package in R software. The Monte Carlo test was adopted based on 499 random permutations.

Results and discussion

Characteristics of hydrolysate and HR

The pH values of the two hydrolysates were 7.63–7.74. The TS and VS concentrations were 2.04 ± 0.09% and 71.55% ± 0.34% in the H4000 hydrolysate, respectively, while they decreased to 1.77 ± 0.21% and 69.89 ± 0.80% in the H10000 hydrolysate due to the increasing centrifugal speed (Fig. 1). The COD, NH4+-N and TN concentrations were 25.9–29.4 g L−1, 669–772 mg L−1 and 1667–1805 mg L−1 in the experimental hydrolysates, owing to the release of the organics and the degradation of nitrogen compounds during HT11. Compared with the H4000 hydrolysate, the COD, NH4+-N and TN concentrations of the H10000 hydrolysate decreased by 11.90%, 9.83%, and 7.63%, respectively, likely owing to the fact that more dissolved organic matter and nitrogen compounds adhere to or adsorbed on particle surfaces were removed with the increasing centrifugal speed from 4000 to 10,000 rpm32. The particle compositions were different in the two hydrolysates. The average particle size of the solids in the H10000 hydrolysate was 769.48 ± 44.55 μm, while it was 1047.12 ± 73.31 μm in the H4000 hydrolysate, indicating that fewer large particles were presented in the H10000 hydrolysate due to the higher centrifugal speed. The experimental HR and swine manure were both rich in cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, total sugar and protein. The lignin content was 20.98% in the HR, owing to the refractory components33. The VS content was 77.48% in the swine manure, while it was 45.55% in the HR owing to a large amount of non-volatile solid retained in the digestate after AD17.

The concentrations of TS and VS (A), NH4+-N, TN and COD (B), and particle size composition (C) in the experimental hydrolysates (i.e., H4000 and H10000), and the specific organic compound contents of total sugar, protein, hemicellulose, cellulose, lignin and VS in the swine manure and HR (D) (** represents significant differences, p < 0.01).

The SEM images suggested that the largest particles occurred in HR, and fewer large particles were presented in the H10000 hydrolysate than in the H4000 hydrolysate due to the higher centrifugal speed (Fig. 2). The average pore diameters of the particles in the H4000 and H10000 hydrolysates, and HR were 11.52, 10.26 and 15.47 nm, respectively (Table S2). Compared with the particles in the H4000 hydrolysate, the specific surface area of particles was higher in the H10000 hydrolysate (9.75 m2 g−1). Further analysis on the functional groups and elemental structures of the hydrothermal products were conducted by FTIR and XPS. The results demonstrated that O–H (3438 cm−1)34, C–H (2924 and 2845 cm−1)35, C=O (1640 cm−1)36 and C–O (1062 cm−1)37 were abundant in all the hydrothermal products. The O–H and C=O peaks of the particles in the H4000 and H10000 hydrolysates were larger than those of HR, indicating the particles in H4000 and H10000 hydrolysates had more O–H and C=O groups. The full scan spectra of XPS revealed that C and O were the major elements in the hydrothermal product, and the percentage of O in HR was higher than that in the particles in the H10000 and H4000 hydrolysates. The high-resolution XPS C 1 s deconvolutions of the hydrothermal products confirmed the existence of C–O, C–C and C=O groups. The area percentage of C=O in the particles in the H10000 and H4000 hydrolysates, and HR was 9.26%, 3.71% and 3.56%, respectively. More C–O presented in the particles in the H4000 hydrolysate and HR than that in the H10000 hydrolysate (Table S2). The area percentage of C–C was 81.55–84.89% in the particles in the H10000 and H4000 hydrolysates, and HR. Since carbon was rich in the hydrolysate particles and HR, all the particles in the H10000 and H4000 hydrolysates, and HR could be called hydrochar38.

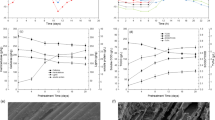

Hydrolysate addition promoting startup and gas production of AD

During the whole experiment, the biogas production was low in NT with a cumulative value of 9.4 mL, indicating that the biogas production generated from the inoculum could be neglected. Compared with CK, the biogas production increased quickly in CL2 and CLS from day 33, which was earlier than in CL1 (day 38) and CK (day 48) (Fig. 3), indicating that hydrolysate addition could prompt the startup of AD. Although the relative biogas production was higher in CL1 than CL2 in the first 35 d, owing to the high COD concentration of hydrolysate. However, the biogas production increased more early in CL2 than in CL 1 after 36 d. The cumulative biogas production was significantly higher in CL2 than in CL1 between days 54 and 82 (p < 0.05) with the relative higher biogas production between days 43 and 82. The NH4+-N concentration was slightly higher in H4000 than in H10000, but they both less than 800 mg L−1, which is reported to have no obviously inhibitory effect on AD performance39. This suggested that the finer hydrochar in the hydrolysate were more favorable for the startup of AD. A higher cumulative biogas production was observed in CL1, CL2 and CLS with the hydrolysate addition than in CK. Wu et al.40 also reported that fine biochar (i.e., 75–150 μm) was more favorable for enhancing the production of medium chain fatty acids with an increased electron transfer efficiency of 92.6% than large particle biochar of 2000–5000 μm. Luo et al.41 found that biochar with smaller particle size was more effective in promoting AD, and was more suitable for methanogens attaching to its surface. Compared with CL1, a higher biogas production was observed in CLS with the addition of H4000 hydrolysate and HR. This indicated that a suitable addition of HR could also accelerate biogas production, likely owing to the conductive materials such as hydrochar and/or organics generated in the HT42.

The cumulative biogas and methane production showed similar trends during the experimental period. At the end of the experiment, the cumulative biogas and methane productions were 267.6–271.8 and 175.3–177.0 mL g-TS−1, respectively, in CL1, CL2 and CLS, which were around 1.4 times of those in CK. This indicated that hydrolysate addition could increase biogas and methane production during AD of swine manure. In CL3 fed only with the hydrolysate (without swine manure), the degradation of organics in the hydrothermal hydrolysate from digestate could produce 24.1 mL g-TSdigestate−1 biogas during the whole experiment.

Hydrolysate addition accelerating organic degradation

In order to well understand the effects of hydrolysate addition on AD performance, the variations of organic concentrations over time were investigated in this study. Since CL3 was only fed with the H4000 hydrolysate and inoculum, the concentrations of organics in CL3 during the entire experiment were not detected. The initial pH value was 6.59–6.67 in the experimental AD reactors (Fig. 4). With the degradation of organic matter, the pH value presented a slight decrease in the first stage. The pH value fluctuated between 6.52 and 6.73 during days 13 and 34 in CL1, CL2 and CLS, which was lower than in CK. This might be attributed to the enhanced hydrolysis, acidogenesis and acetogenesis occurring in CL1, CL2 and CLS. Similarly, low biogas and methane production were observed during this period. After that, the pH value increased to 7.91–8.28 between days 62 and 100 in the AD reactors, which was consistent with the high biogas and methane production. This indicated that methanogenesis was dominant in the AD reactors after day 34.

Hydrolysate was rich in organics such as VFAs and reducing sugar, which were released from the hydrolysis of macromolecular organics during HT9,43. The hydrolysate addition increased the COD concentration in the AD samples, owing to the abundant organics in the hydrolysate such as soluble sugar and soluble protein (Fig. S1). An increased concentrations of soluble sugar and soluble protein were also observed in CL1, CL2 and CLS. With the degradation of organic matters, the COD concentrations increased, and reached the maximum values in the AD samples on day 34. It was consistent with the decreasing pH value on day 34. This indicated that hydrolysis, acidogenesis, and acetogenesis reactions were dominant in the first 34 d. After day 34, the COD concentrations decreased and dropped to 15.13–22.33 g L−1 in the AD samples on day 100. Compared with CK, higher COD concentrations remained in the AD reactors with the hydrolysate addition (p < 0.005), likely owing to the refractory organics such as soluble protein in the hydrolysate44. Compared with the soluble sugar, the soluble protein was more difficult to degrade in AD. The soluble protein remaining in the AD samples of swine manure with hydrolysate addition was significantly higher than that in CK (p < 0.001), suggesting that high refractory organics remained in the hydrolysate. Similarly, Zhong et al.45 reported that solid protein and soluble protein in the hydrolysate were the main nitrogen compounds during hydrothermal treatments. The change in protein structure might influence the biodegradability of soluble protein in the hydrolysate46.

Acetic acid, propionic acid and butyric acid were the main VFAs during AD. With the degradation of organics, the VFA concentrations increased and reached the peaks on day 34, which was consistent with the increasing COD concentrations and the decreasing pH values. After that, the VFA concentrations decreased with time. However, propionic acid decreased after day 62. This might be attributed to the pH value of ~ 8 between days 34 and 62, which led to propionic acid-enriched VFAs production47. Compared with CK, the VFA concentrations decreased more quickly in CL1, CL2, and CLS. This indicated that a faster VFA degradation occurred in the AD reactors with the hydrolysate addition. Pentanoic acid was not detected in CL2 and CLS on day 62, while it was not detected in CK and CL1 on day 100, suggesting that a faster organic degradation occurred in CL2 and CLS than in CK and CL1.

During the AD process, organic matters are mainly degraded into CH4 and CO2 by microorganisms48. After the operation of 100 d, the TS concentration decreased from the initial value of 12.32–13.76% to 7.23–7.88% with degradation efficiencies of 38.6–45.5% (Fig. S2). The VS concentrations decreased from 75.37–79.39% to 66.3–68.78% in the AD reactors. Total sugar, protein, hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin were the main organic matter in the swine manure. During the AD process, the contents of total sugar, hemicellulose and cellulose decreased, while the contents of protein and lignin increased indicating that organic matters such as total sugar, hemicellulose and cellulose presented rapid degradation, especially the total sugar could quickly be converted into biogas (mainly methane and CO2). Compared with total sugar, the contents of hemicellulose and cellulose, protein decreased slowly. During AD, the degradation efficiencies of protein were 20.2%-34.1% in the experimental treatments. However, almost no lignin was degraded during AD, owing to the complicated composition of lignin49.

Electron transfer capacity and conductivity of hydrolysate

The specific conductance of the hydrolysates, swine manure, and their mixture with HR was investigated (Fig. 5). The conductivity was 10.62 ± 0.04 and 10.72 ± 0.02 mS cm−1 of the H4000 and H10000 hydrolysate, respectively, which were higher than those of tap water (0.13 mS cm−1) and tap water with manure (i.e., the conductivity of swine manure slurry, 2.59 ± 0.07 mS cm−1), owing to the abundant compounds in the hydrolysate released during HT such as VFAs and NH4+9. When the hydrolysate was added to the swine manure, the conductivities of the mixture increased about 4.4 times (11.43–11.69 mS cm−1) compared with the control without hydrolysate. And the addition of HR into the H4000 hydrolysate and manure mixture further increased the specific conductance to 12.35 mS cm−1. The higher conductivity of the mixture with hydrolysates might improve the electron transfer rate50.

The conductivities (A), cyclic voltammetry (B) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (C) of the experiment materials. H4000 and H10000 in Figure B and C denote the fine hydrochar in the H4000 and H10000 hydrolysate, respectively. Different letters in the figure denote significant difference at p < 0.05.

CV is used to denote the capacitive characteristics of the hydrochar in hydrolysate, manure and HR samples, owing to the area enclosed by CV curve positively related with the capacitance51. The fine particles in the H4000 and H10000 hydrolysates were dried and then dropcasted on a stainless steel substrate to prepare fine particle-modified electrodes for electrochemical property tests. Within the scan range of − 0.1 ~ 1.1 V vs. SEC, the stainless steel electrode didn’t show obvious current change, while the electrodes with sample loading on the stainless steel substrate surfaces demonstrated a large current increase during the positive scan, suggesting that the sample particles had better electro-activity than that of stainless steel in the scan range. With the modification of H4000 and H10000 hydrochar, the specific capacitance of the electrodes was 23.67 and 26.08 F g−1, respectively, which was only around half of that with the HR modification and 40% of that with the solid manure modification. It indicated that the hydrochar in the H4000 and H10000 hydrolysate could store more charges than the HR and manure particles, which could enhance the number of available active sites30. Besides, there was no obvious redox peak in the experimental materials, indicating that the redox reactions were not the main role in enhancing electron transfer50.

To explore the resistance characteristics of the sample materials, EIS was conducted for the prepared working electrodes. The diameter of the semicircle in the high-frequency region in the Nyquist plot represents the charge-transfer resistance (Rct) of the electrodes, and the straight line in the low-frequency region represents the Warburg resistance (W0)52. The Rct of the H4000 and H10000 hydrochar-modified electrodes was 25.12 and 29.2 Ω, respectively, which was significantly lower than that of HR (113.7 Ω) and swine manure (95.7 Ω) modified electrode (Table S3), suggesting that the fine hydrochar in the hydrolysates had higher electron transfer activity. The superior charge-transfer properties of the fine hydrochar might mainly contribute to the good AD performance of swine manures, with the better work of the finer H10000 hydrochar.

Effects of hydrolysate addition on microbial community

Microbial diversity varies with treatments and time during the AD process (Fig. S2). Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota and Synergistota were the main phyla in the experimental AD reactors, accounting for 95.1–99.7% of the total sequencing reads (Fig. 6). Compared with bacteria, the relative abundance of archaea was lower in the AD reactors (less than 0.05%). In our previous study, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota were also found to be the predominant microorganisms in the AD reactors with the addition of Fe-modiffed digestate hydrochar53. Clostridium sensu stricto 1, Ruminofilibacter, Proteiniphilum, Thiopseudomonas, Advenella, Hydrogenispora, Caldicoprobacter, Terrisporobacter, Tepidimicrobium, Petrimonas and Advenella were the predominant genera in the experimental AD reactors, which mainly belonged to the hydrolytic bacteria, acidogenic bacteria, and acetogentic bacteria. The microbial community structures changed with the substrate biodegradation in the AD reactors. In the initial stage (day 1), the degrading microorganisms of multiple sugars and hydrocarbon such as Clostridium sensu stricto 1, Terrisporobacter, Turicibacter and Romboutsia dominated in the reactors, which were positively correlated with the concentrations of VFA, TS, cellulose, hemicellulose sugar and COD. The variation in the relative abundance of these genera could indicate the decomposition of the easily biodegradable organics. For example, the relative abundance of Clostridium sensu stricto 1 was high in the initial AD samples with the values of 3.9–15.8%, and increased a little in the AD reactors in the first 34 d. After that, the relative abundance of Clostridium sensu stricto 1 decreased to 2.6–3.4% in CL1, CL2 and CLS on day 62, while it kept a high value of 17.0% in CK. This suggested a faster degradation of multiple sugars occurred in CL1, CL2 and CLS. Similarly, Terrisporobacter, a strictly anaerobic bacterium that can degrade carbohydrate raw materials into acetic acid54, dominated the AD reactors on day 1 with the relative abundance of 1.2–3.6%. With the degradation of organic matter, the relative abundance of Terrisporobacter reached a peak on day 13 or 34. Then it decreased to below 1% in CL1, CL2 and CLS on day 62, while it was 3.1% in CK. This also indicated that a faster hydrocarbon degradation occurred in CL1, CL2 and CLS than that in CK. With the degradation of easily biodegradable organics and VFA production, microorganisms involved in small molecule organic degradation such as Thiopseudomonas, Tepidimicrobium, Petrimonas, Advenella, Fermentimonas, Sporanaerobacter and protein-degrading bacteria Proteiniphilum began rapid growth and reached the high peak in the relative abundance between days 13 and 3455. Except for Proteiniphilum, the relative abundances of the small molecule organics-degrading microorganisms were positively correlated with the VFA concentrations. The relative abundance of Proteiniphilum was low with the values of 0.14–0.59% in the AD reactors on day 1. With the degradation of organic matters, the relative abundance of Proteiniphilum increased and reached the peak in CL2 and CLS on day 34, and then decreased to 5.8–7.8% in the end, while it kept a high value of 17.5–20.6% in CK and CL1. This suggested that a fast protein degradation occurred in CL2 and CLS. After the consumption of biodegradable organics such as protein and sugars, lignocellulose-degrading bacteria including Ruminofilibacter, Herbinix and Caldicoprobacter became dominant in the AD reactors between days 62 and 100. The relative abundances of Ruminofilibacter and Caldicoprobacter increased from less than 0.15% on day 1 to 9.8–34.5% and 3.3–11.9%, respectively, in the AD reactors between days 62 and 100. This was consistent with the high removals of cellulose and hemicellulose in the AD reactors. Hydrogenispora are acetogenic bacteria, which have been reported to dominate in the later stage of AD, and can work as a indicator for AD stage19. The relative abundance of Hydrogenispora increased from less than 0.04% to 1.2%-6.1% in CL1, CL2 and CLS on day 62, while it was 0.13% in CK, suggesting that a faster AD occurred in CL1, CL2 and CLS than in CK. The correlation analysis of environmental factors, biogas and methane production rates, and the main genera also showed that the relative abundances of Ruminofilibacter, Herbinix, Caldicoprobacter, Proteiniphilum and Hydrogenispora were significantly correlated with the methane production rate.

Taxonomic classification of bacterial 16S rRNA gene at phylum level (A) and main genera (B), heat map of correlation between the main genera and environmental factors (C), the relative abundance of methanogens (D), and canonical correlation analysis (CCA) of microbial communities and environmental factors (E) in the AD reactors. The number after the rod in the sample name denotes the sampling time. * represents P < 0.05. ** represents P < 0.01.

Hydrogenotrophic methanogens including Methanobrevibacter, Methanoculleus, Methanosphaera, Candidatus Methanoplasma, Methanofollis and Methanomassiliicoccus, RumEn M2 and Methanoculleus56,57,58,59 were the dominant genera for methanogenesis in the experimental AD reactors (Fig. 4D). Among them, Methanosphaera, Candidatus Methanoplasma, Methanofollis and Methanomassiliicoccus, RumEn M2 and Methanoculleus were also capable of converting methyl compounds into methane56,57,58,59. Similarly, Hu et al.60 found that hydrogenotrophic methanogens predominated in the AD reactor of swine manure with the relative abundance of 90.2%, while acetoclastic methanogens were not detected. In the initial samples, Methanobrevibacter and Methanosphaera predominated in the AD reactors. With the degradation of organic matter, the methanogenic community varied. In CK, Candidatus Methanoplasma, Methanofollis, Methanoculleus and RumEn M2 became dominant on day 100. Compared to CK and CL1, the relative abundances of Candidatus Methanoplasma and Methanoculleus were higher in CL2 and CLS in the end.

CCA analysis showed that the microbial communities in the AD reactors at the same sampling points clustered together except for the CK-62 sample, indicating that the AD time was the most important factor in affecting microbial community structure. Among all the detected environmental factors, TS and isobutyric acid had significant effects on the microbial communities (p < 0.005). Between days 13 and 34, VFAs had significant influences on the microbial communities (p < 0.05), which might be because they were the major substrates for microbial growth and metabolism at this stage.

Mechanisms of hydrolysate addition on AD performance

Exoelectrogenic bacteria have been reported to be abundant in the AD system to transfer electrons to methanogens through cell components, such as c-type cytochrome and e-pili61,62. Compared with interspecies electron transfer using H2 or formate as the electron carrier, DIET has a more prominent capacity to accelerate the degradation of organic matter in AD systems63. The enhancement in methane production by conductive materials is often correlated with a high abundance of potential exoelectrogenic bacteria51. In this study, there were about 20 known potential exoelectrogenic bacteria detected in the AD reactors (Fig. 7 and Table S4). Defluviitoga, Syntrophomonas, Lentimicrobium, Comamonas, Lysinibacillus, Enterococcus and Desulfovibrio were the main potential exoelectrogenic bacteria in the AD reactors. The relative abundance of potential exoelectrogenic bacteria was 0.27–0.97% in the initial AD samples. With the degradation of organic matter, the relative abundance of potential exoelectrogenic bacteria increased to 3.7–9.1% in CL1, CL2 and CLS in the end, which was higher than that in CK (1.7%). This suggested that the hydrolysate addition could promote the growth of potential exoelectrogenic bacteria, enhance the DIET process between bacteria and methanogens owing to the good conductivity of hydrochar (shown by CV and EIS in Fig. 5), and thus accelerate the degradation of organics such as VFAs and increase the biogas and methane production64.

The relative abundance of potential exoelectrogens bacteria in the AD reactors (A), heat map of correlation between the potential exoelectrogens bacteria and environmental factors (B), and correlation analysis of environmental factors, biogas and methane production rates, and their Mantel test analysis for potential exoelectrogens bacteria community (C) in the AD reactors, with a color gradient denoting Spearman’s correlation.

Heat map visualizing correlation between the main potential exoelectrogenic bacteria and environmental factors were drawn based on Pearson correlation analysis (Fig. 7). The potential exoelectrogenic bacteria including Syntrophomonas, Desulfovibrio, Syntrophaceticus, Defluviitoga and Pelotomaculum were positively correlated with pH, protein, lignin and methane production rate. Compare with CK, the relative abundance of Syntrophomonas, Desulfovibrio, Syntrophaceticus, Defluviitoga and Pelotomaculum was higher in the treatments with hydrolysate addition, especially in CL2 with the addition of H10000 hydrolysate. This suggested that the hydrolysate addition could prompt the growth of exoelectrogenic bacteria, especially the finer hydrochar in the hydrolysate.

The correlation analysis of environmental factors, biogas and methane production rates, and their Mantel test analysis for potential exoelectrogenic bacteria showed that pH, TS, hemicellulose and cellulose, sugar, protein and lignin had the strongest correlations with potential exoelectrogenic bacteria community in the AD reactors with a mantels’r above 0.4 and P < 0.01. Isovaleric acid, soluble sugar and methane production rate were significantly correlated with potential exoelectrogenic bacterial community (0.01 < P < 0.05). This indicated that organic matter including hemicellulose and cellulose, sugar, protein, lignin and pH were the main factor in affecting the community of potential exoelectrogenic bacteria.

Nutrients in hydrolysate have been reported to be responsible for boosting the growth of the functional microbial community, especially exoelectrogenic bacteria65. In this study, although there were more NH4+-N, TN, COD, TS and VS in the H4000 hydrolysate than those in the H10000 hydrolysate, the H10000 hydrolysate was more favorable for biogas production. This indicated that the hydrochar in the H10000 hydrolysate were better in prompting AD startup and performance than that in the H4000 hydrolysate. Further study on the hydrochar in the hydrolysates revealed that the average particle size of the solids in the H10000 hydrolysate was 26.51% smaller than that in the H4000 hydrolysate. The finer hydrochar possessed higher charge storage capability, and lower electron-transfer resistance. Additionally, compared with CL1, a high relative abundance of potential exoelectrogenic bacteria was observed in CL2 and CLS, indicating that the hydrochar in the H10000 hydrolysate was more optimal to facilitate the growth of potential exoelectrogenic bacteria than that in the H4000 hydrolysate. The higher electron-transfer properties of the fine hydrochar in the hydrolysate might be the major reason to enhance the DIET process and microbial activity in AD.

Taken together, we hypothesized the mechanisms of hydrolysate addition in the AD systems as shown in Fig. 8. The superior charge storage capability, and electron-transfer activity of the fine hydrochar in the hydrolysate improve the DIET process and microbial activity to prompt AD startup and performance. The fine hydrochar in the hydrolysate could work as conductive materials, which could facilitate the growth of potential exoelectrogenic bacteria such as Defluviitoga, Syntrophomonas and Lentimicrobium, and increase the extracellular electron transfer between bacteria and methanogens in AD systems. Additionally, the organics in hydrolysate could also promote the growth of hydrolytic bacteria, acetogenic bacteria and acidogenic bacteria, which could accelerate the degradation of macromolecular substrates such as sugar, protein, cellulose and hemicellulose to generate VFAs, H2 and CO2. Thus, the AD performance was enhanced by the hydrolysate addition. Hydrogeno-trophic methane production might be the main pathway in the AD reactors, but we also did not rule out acetoclastic methane production occurred in this system. Further studies such as methanogenic abundance and activity need to be conducted to illustrate the influencing mechanisms of hydrolysate on methane production.

Conclusions

Fine hydrochar was rich in the hydrolysate despite of high centrifugal speeds of 4000–10,000 rpm. Compared with HR, the hydrochar in the H4000 and H10000 hydrolysates had more O–H and C=O functional groups. The hydrochar in the H10000 hydrolysate had more C=O, while the hydrochar in the H4000 hydrolysate and HR had more C–O. Although the concentrations of organics such as COD were higher in the H4000 hydrolysate than in the H10000 hydrolysate, more biogas was produced in the co-digestion of the H10000 hydrolysate and swine manure. Compared with the larger hydrochar, the finer hydrochar in the H4000 and H10000 hydrolysates were more optimal for facilitating the growth of potential exoelectrogenic bacteria. Moreover, the fine hydrochar had higher charge storage capability, and lower electron-transfer resistance that could enhance the DIET process and microbial activity. These findings provided new insights into the mechanisms of hydrolysate in prompting AD startup and performance. Since the hydrolysates obtained only from two centrifugal speeds were used in this study, the influence of fine hydrochar in the hydrolysate on AD performance might be interfered by the complex components in hydrolysates. Further studies such as effects of a wider range of centrifugal speeds, and particle sizes of hydrochar on AD performance and microbial activity should be conducted to illustrate the role of hydrochar and develop AD techniques for swine manure treatment.

Data availability

Raw reads obtained in this study are available at the NCBI Short Read Archive (SRA) under the accession number PRJNA916386.

References

Zubair, M. et al. Biological nutrient removal and recovery from solid and liquid livestock manure: Recent advance and perspective. Bioresour. Technol. 301, 122823 (2020).

Khalid, A., Arshad, M., Anjum, M., Mahmood, T. & Dawson, L. The anaerobic digestion of solid organic waste. Waste Manage 31, 1737–1744 (2011).

Yadav, M. et al. Organic waste conversion through anaerobic digestion: A critical insight into the metabolic pathways and microbial interactions. Metab. Eng. 69, 323–337 (2022).

Ahn, H. K., Smith, M. C., Kondrad, S. L. & White, J. W. Evaluation of biogas production potential by dry anaerobic digestion of switchgrass-animal manure mixtures. Appl. Biochem. Biotech. 160, 965–975 (2010).

Nasir, I. M., Mohd Ghazi, T. I. & Omar, R. Anaerobic digestion technology in livestock manure treatment for biogas production: A review. Eng. Life Sci. 12, 258–269 (2012).

Marzbali, M. H. et al. Wet organic waste treatment via hydrothermal processing: A critical review. Chemosphere 279, 130557 (2021).

Song, B. et al. Recent advances and challenges of inter-disciplinary biomass valorization by integrating hydrothermal and biological techniques. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 135, 110370 (2021).

Ghimire, N., Bakke, R. & Bergland, W. H. Liquefaction of lignocellulosic biomass for methane production: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 332, 125068 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Additional ratios of hydrolysates from lignocellulosic digestate at different hydrothermal temperatures influencing anaerobic digestion performance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 32866–32881 (2023).

Mayer, F., Bhandari, R. & Gäth, S. A. Life cycle assessment on the treatment of organic waste streams by anaerobic digestion, hydrothermal carbonization and incineration. Waste Manage 130, 93–106 (2021).

Wang, F. et al. Anaerobic co-digestion of corn stover and wastewater from hydrothermal carbonation. Bioresour. Technol. 315, 123788 (2020).

Zhao, Z. et al. Promoting the overall energy profit through using the liquid hydrolysate during microwave hydrothermal pretreatment of wheat straw as co-substrate for anaerobic digestion. Sci. Total Environ. 857, 159463 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Bamboo derived hydrochar microspheres fabricated by acid-assisted hydrothermal carbonization. Chemosphere 263, 128093 (2021).

Ahmed, M. et al. Anaerobic degradation of digestate based hydrothermal carbonization products in a continuous hybrid fixed bed anaerobic filter. Bioresour. Technol. 330, 124971 (2021).

Ayodele, O. O. et al. Stabilization of anaerobic co-digestion of biowaste using activated carbon of coffee ground biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 319, 124247 (2021).

Wang, C., Wei, W., Zhang, Y. T., Chen, X. & Ni, B. J. Hydrochar alleviated the inhibitory effects of polyvinyl chloride microplastics and nanoplastics on anaerobic granular sludge for wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 452, 139302 (2023).

Sun, K. et al. Chemical and microbiological characterization of pig manures and digestates. Environ. Technol. 44, 1916-1925SS (2023).

Liao, D. et al. Hydrothermal treatment enhances energy recovery from pig manure digestate and improves the properties of residues. J. Environ. Sci. Health Pt. A 58, 116–126 (2023).

Kang, Y. R. et al. Effects of different pretreatment methods on biogas production and microbial community in anaerobic digestion of wheat straw. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 51772–51785 (2021).

Xu, Z. et al. Green synthesis of nitrogen-doped porous carbon derived from rice straw for high-performance supercapacitor application. Energy Fuels 34, 8966–8976 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Methane oxidation in landfill waste biocover soil: kinetics and sensitivity to ambient conditions. Waste Manage. 31, 864–870 (2011).

Eaton, A., Clesceri, L. S. & Greenberg, A. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater (American Public Health Association, 2005).

Eskicioglu, C., Kennedy, K. J. & Droste, R. L. Characterization of soluble organic matter of waste activated sludge before and after thermal pretreatment. Water Res. 40, 3725–3736 (2006).

Li, J., Chen, T., Yin, J. & Shen, D. Effect of nano-magnetite on the propionic acid degradation in anaerobic digestion system with acclimated sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 334, 125143 (2021).

Urbat, F., Müller, P., Hildebrand, A., Wefers, D. & Bunzel, M. Comparison and optimization of different protein nitrogen quantitation and residual protein characterization methods in dietary fiber preparations. Front. Nutr. 6, 127 (2019).

Yue, F. et al. Effects of monosaccharide composition on quantitative analysis of total sugar content by phenol-sulfuric acid method. Front. Nutr. 9, 963318 (2022).

Van Soest, P. V., Robertson, J. B. & Lewis, B. A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 74, 3583–3597 (1991).

Wang, L. et al. Effect of particle size on the performance of autotrophic nitrogen removal in the granular sludge bed reactor and microbiological mechanisms. Bioresour. Technol. 157, 240–246 (2014).

Wang, J. et al. CS2 increasing CH4-derived carbon emissions and active microbial diversity in lake sediment. Environ. Res. 208, 112678 (2022).

He, R. et al. Conversion of sulfur compounds and microbial community in anaerobic treatment of fish and pork waste. Waste Manage 76, 383–393 (2018).

Naderi, H. R., Mortaheb, H. R. & Zolfaghari, A. Supercapacitive properties of nanostructured MnO2/exfoliated graphite synthesized by ultrasonic vibration. J. Electroanal. Chem. 719, 98–105 (2014).

Saha, S. et al. Verification of the solid-liquid separation of waterlogged reduced soil via a centrifugal filtration method. Soil Syst. 8, 61 (2024).

Zheng, W., Phoungthong, K., Lü, F., Shao, L. M. & He, P. J. Evaluation of a classification method for biodegradable solid wastes using anaerobic degradation parameters. Waste Manage 33, 2632–2640 (2013).

Yuan, S. & Dai, X. H. Facile synthesis of sewage sludge-derived mesoporous material as an efficient and stable heterogeneous catalyst for photo-Fenton reaction. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 154, 252–258 (2014).

Silva, J. O. et al. Thermal analysis and FTIR studies of sewage sludge produced in treatment plants. The case of sludge in the city of Uberlândia-MG, Brazil. Thermochim. Acta 528, 72–75 (2012).

Yu, X. et al. Promotion effect of KOH surface etching on sucrose-based hydrochar for acetone adsorption. Appl. Surf. Sci. 496, 143617 (2019).

Obreja, A. C. et al. Isocyanate functionalized graphene/P3HT based nanocomposites. Appl. Surf. Sci. 276, 458–467 (2013).

Kambo, H. S. & Dutta, A. A comparative review of biochar and hydrochar in terms of production, physico-chemical properties and applications. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 45, 359–378 (2015).

Park, S. & Kim, M. Effect of ammonia on anaerobic degradation of amino acids. Ksce J. Civ. Eng. 20, 129–136 (2016).

Wu, S. L. et al. Revealing the mechanism of biochar enhancing the production of medium chain fatty acids from waste activated sludge alkaline fermentation liquor. ACS ES&T Water 1, 1014–1024 (2021).

Luo, C., Lü, F., Shao, L. & He, P. Application of eco-compatible biochar in anaerobic digestion to relieve acid stress and promote the selective colonization of functional microbes. Water Res. 68, 710–718 (2015).

Cavali, M. et al. A review on hydrothermal carbonization of potential biomass wastes, characterization and environmental applications of hydrochar, and biorefinery perspectives of the process. Sci. Total Environ. 857, 159627 (2023).

Ahmad, F., Silva, E. L. & Varesche, M. B. A. Hydrothermal processing of biomass for anaerobic digestion—A review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 98, 108–124 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Energy recovery from high ash-containing sewage sludge: Focusing on performance evaluation of bio-fuel production. Sci. Total Environ. 843, 157083 (2022).

Zhong, M., Yang, D., Liu, R., Ding, Y. & Dai, X. Effects of hydrothermal treatment on organic compositions, structural properties, dewatering and biogas production of raw and digested sludge. Sci. Total Environ. 848, 157618 (2022).

Chen, R., Dai, X. & Dong, B. Decrease the effective temperature of hydrothermal treatment for sewage sludge deep dewatering: Mechanistic of tannic acid aided. Water Res. 217, 118450 (2022).

Feng, L., Chen, Y. & Zheng, X. Enhancement of waste activated sludge protein conversion and volatile fatty acids accumulation during waste activated sludge anaerobic fermentation by carbohydrate substrate addition: The effect of pH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 4373–4380 (2009).

Kunatsa, T. & Xia, X. A review on anaerobic digestion with focus on the role of biomass co-digestion, modelling and optimisation on biogas production and enhancement. Bioresour. Technol. 344, 126311 (2022).

Shahzadi, T. et al. Advances in lignocellulosic biotechnology: A brief review on lignocellulosic biomass and cellulases. Adv. Biosci. Biotech. 5, 246–251 (2014).

Wang, C. et al. Responsiveness extracellular electron transfer (EET) enhancement of anaerobic digestion system during startup and starvation recovery stages via magnetite addition. Bioresour. Technol. 272, 162–170 (2019).

Yin, C. et al. Sludge-based biochar-assisted thermophilic anaerobic digestion of waste-activated sludge in microbial electrolysis cell for methane production. Bioresour. Technol. 284, 315–324 (2019).

Zhao, S., Wang, C. Y., Chen, M. M., Wang, J. & Shi, Z. Q. Potato starch-based activated carbon spheres as electrode material for electrochemical capacitor. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 70, 1256–1260 (2009).

Shen, Y., Zhan, X., Ye, M., Zha, X. & He, R. Effects of Fe-modiffed digestate hydrochar at different hydrothermal temperatures on anaerobic digestion of swine manure. Bioresour. Technol. 395, 130393 (2024).

Cho, H. U., Kim, Y. M. & Park, J. M. Changes in microbial communities during volatile fatty acid production from cyanobacterial biomass harvested from a cyanobacterial bloom in a river. Chemosphere 202, 306–311 (2018).

Chen, S. & Dong, X. Proteiniphilum acetatigenes gen. nov., sp. Nov., from a UASB reactor treating brewery wastewater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55, 2257–2261 (2005).

Shi, J. et al. Effect of thermal hydrolysis pretreatment on anaerobic digestion of protein rich biowaste: Process performance and microbial community structures Shift. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 1–17 (2022).

Chen, S. C. et al. Methanofollis fontis sp. Nov., a methanogen isolated from marine sediment near a cold seep at Four-Way Closure Ridge offshore southwestern Taiwan. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 70, 5497–5502 (2020).

Pyzik, A. et al. Comparative analysis of deep sequenced methanogenic communities: Identification of microorganisms responsible for methane production. Microb. Cell Fact. 17, 197 (2019).

Palevich, N. et al. Complete genome sequence of Methanosphaera sp. ISO3-F5, a rumen methylotrophic methanogen. Microbiol. Resour. Ann. 13, e00043-e124. https://doi.org/10.1128/mra.00043-24 (2024).

Hu, Y. Y. et al. Study of an enhanced dry anaerobic digestion of swine manure: Performance and microbial community property. Bioresour. Technol. 282, 353–360 (2019).

Rotaru, A. E. et al. A new model for electron flow during anaerobic digestion: Direct interspecies electron transfer to Methanosaeta for the reduction of carbon dioxide to methane. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 408–415 (2014).

Ren, S. et al. Hydrochar-facilitated anaerobic digestion: Evidence for direct interspecies electron transfer mediated through surface oxygen-containing functional groups. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 5755–5766 (2020).

Zhao, Z. et al. Why do DIETers like drinking: Metagenomic analysis for methane and energy metabolism during anaerobic digestion with ethanol. Water Res. 171, 115425 (2020).

Shi, Z. et al. Genome-centric metatranscriptomics analysis reveals the role of hydrochar in anaerobic digestion of waste activated sludge. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 8351–8361 (2021).

Wang, Z., Lee, T., Lim, B., Choi, C. & Park, J. Microbial community structures differentiated in a single-chamber air-cathode microbial fuel cell fueled with rice straw hydrolysate. Biotechnol. Biofuels 7, 1–10 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Central Guide Local Science and Technology Development of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region with Grant No. ZYYD2023B16, Open Project Program of Xinjiang Biomass Solid Waste Resources Technology and Engineering Center with Grants No. KSUGCZX202303 and KSUGCZX202510, and Kashi University research project with Grant No. (2023)2846.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xianghao Zha: Methodology, Data curation, Investigation. Feixing Li: Methodology, Data curation, Investigation. Yan Shen: Methodology, Data curation, Investigation. Xin Zhang: Methodology, Data curation. Ruo He: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zha, X., Li, F., Shen, Y. et al. Fine hydrochar in hydrothermal hydrolysate promotes startup and gas production of swine manure anaerobic digestion. Sci Rep 15, 22873 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06044-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06044-3