Abstract

Although the relationship between depression and cognitive dysfunction has been extensively documented, research examining the intermediary role of metacognitive processes remains surprisingly limited. This study employed advanced network analytical techniques to elucidate the complex interrelationships between metacognitive beliefs, depressive symptomatology, subjective cognitive complaints (SCCs), and objective cognitive performance in clinical and non-clinical populations. Using a rigorously selected sample of participants with major depressive disorder (MDD; n = 146) and demographically matched controls (n = 138), we constructed regularized partial correlation networks to identify central nodes and bridge pathways. Results revealed that negative metacognitive beliefs specifically beliefs about uncontrollability and danger of thoughts—demonstrated the highest centrality indices (strength) and formed critical bridge connections between depressive symptoms and SCCs. Importantly, the network architecture differed significantly between MDD and control groups (Network Comparison Test: M = 0.28, p = .003), with the MDD network exhibiting stronger connectivity between metacognitive nodes and subjective cognitive complaints (∆edge = 0.31, p < .01). Longitudinal analyses utilizing graphical vector autoregression models (n = 167) demonstrated that changes in metacognitive beliefs temporally preceded alterations in both depressive symptoms (β = 0.34, p < .001) and subjective cognitive complaints (β = 0.29, p < .01), independent of objective cognitive performance. These findings provide compelling evidence for the metacognitive model of depression and suggest that interventions targeting maladaptive metacognitive beliefs may effectively address both mood symptoms and subjective cognitive dysfunction, even in the absence of objective cognitive impairment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cognitive dysfunction represents a core feature of major depressive disorder (MDD), with implications for treatment response, functional recovery, and overall illness trajectory1. While objective cognitive deficits in domains of attention, memory, and executive function have been well-documented in depression2, subjective cognitive complaints (SCCs) – that is, self-perceived difficulties in cognitive functioning – often demonstrate stronger associations with depressive symptoms than with actual cognitive performance3,4. This discrepancy between subjective experience and objective performance presents a significant clinical challenge, as SCCs contribute substantially to functional impairment and quality of life reductions independent of objective cognitive status5. Notably, depressed individuals often report cognitive difficulties out of proportion to their measured performance, suggesting that metacognitive factors and negative appraisals6 rather than objective deficits drive these complaints7. The metacognitive model of depression8 offers a potentially illuminating framework for understanding this disconnection between subjective and objective measures. Metacognition—defined as cognition about cognition—encompasses beliefs, processes, and strategies that monitor, control, and appraise cognitive functioning9. Wells and Matthews1 propose that maladaptive metacognitive beliefs contribute to psychopathology through a cognitive-attentional syndrome (CAS) characterized by perseverative thinking (worry/rumination), threat-focused attention, and unhelpful coping behaviors. Two types of metacognitive beliefs appear particularly relevant to depression: positive beliefs about rumination (e.g., “Ruminating helps me find solutions”) and negative beliefs about the uncontrollability and danger of thoughts (e.g., “My worrying thoughts are uncontrollable”)10. According to the metacognitive model, positive beliefs drive individuals to engage in rumination (believing it will help solve problems), whereas negative beliefs about uncontrollability and danger create distress and a sense of helplessness regarding one’s thoughts. These beliefs in combination fuel the CAS, perpetuating rumination and self-focus that maintain depression and potentially skew subjective cognitive experiences. While substantial evidence supports the role of metacognitive beliefs in depressive symptomatology11,12, their relationship to cognitive functioning in depression has received limited investigation. Several theoretical mechanisms might explain how metacognitive processes could influence the relationship between depression and cognitive functioning:

-

Attentional resource allocation: Negative metacognitive beliefs may perpetuate self-focused attention and rumination, thereby depleting cognitive resources available for external task demands13.

-

Negative interpretive bias: Maladaptive metacognitive beliefs might bias the interpretation of cognitive lapses, amplifying the subjective experience of cognitive failure14.

-

Cognitive confidence: Reduced confidence in cognitive abilities may increase hypervigilance toward cognitive lapses and discourage implementation of compensatory strategies15.

Network analysis offers a particularly valuable methodological approach for investigating these complex interrelationships. Unlike traditional latent variable models, network models conceptualize psychological constructs as systems of interacting components, allowing for the identification of central nodes (variables with strongest connections to other variables) and bridge nodes (variables that connect different domains)16. This approach has yielded important insights into depression17 and cognitive functioning18, but has not been applied to examining the metacognitive underpinnings of depression-related cognitive dysfunction. Additionally, we incorporated a temporal network approach to explore dynamic, directional relationships among these variables over time. Temporal network analysis (e.g., graphical vector autoregression) models how variables at one time point predict changes in others at later time points, providing insight into directional influences that cross-sectional networks cannot address19. The present study employs both cross-sectional and temporal network analysis to investigate the interrelationships between metacognitive beliefs, depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive complaints, and objective cognitive performance20,21. We hypothesized that: (1) metacognitive beliefs would demonstrate strong centrality in the overall network; (2) negative metacognitive beliefs would serve as bridge nodes connecting depressive symptoms with subjective cognitive complaints; (3) network structure would differ significantly between MDD and control groups, with more pronounced connections involving metacognitive beliefs in the MDD network; and (4) longitudinally, changes in metacognitive beliefs would temporally precede changes in depressive symptoms and subjective cognitive complaints. We focused on negative (rather than positive) metacognitive beliefs as likely bridges because negative beliefs (e.g., “I cannot control my thoughts”) directly amplify distress and cognitive worry, whereas positive beliefs (e.g., “Worrying helps me cope”) primarily encourage rumination without directly linking mood and cognitive complaints.

Methods

Participants

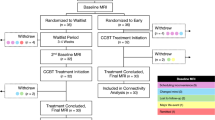

The study sample comprised 284 participants: 146 individuals meeting DSM-5 criteria for MDD and 138 healthy controls without current or past psychiatric disorders. MDD participants were recruited from hospitals and healthy controls were recruited through local community advertisements. MDD diagnosis was established using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5; First et al., 2015). Inclusion criteria for the MDD group were: (1) primary diagnosis of MDD; (2) minimum score of 14 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D); (3) age 18–65 years; and (4) fluency in English. Exclusion criteria included: (1) history of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, or organic brain syndromes; (2) substance use disorder within the past 6 months; (3) intellectual disability (IQ < 70); (4) electroconvulsive therapy within the past 6 months; and (5) significant change in psychotropic medication within the past 4 weeks. Healthy controls were matched to the MDD group on age, sex, and education, and screened for absence of current or lifetime psychiatric disorders using the SCID-5. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. A subset of participants (n = 167; 89 MDD and 78 controls) completed follow-up assessments at 6-month and 12-month time points to enable longitudinal analyses. Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

Measures

Metacognitive beliefs

The Metacognitions Questionnaire-301 assessed five dimensions of metacognitive beliefs: (1) positive beliefs about worry (e.g., “Worrying helps me cope”); (2) negative beliefs about uncontrollability and danger of thoughts (e.g., “When I start worrying, I cannot stop”); (3) cognitive confidence (e.g., “I have a poor memory”); (4) need for control (e.g., “Not being able to control my thoughts is a sign of weakness”); and (5) cognitive self-consciousness (e.g., “I pay close attention to the way my mind works”). Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = “do not agree” to 4 = “agree very much”), with higher scores indicating more pronounced metacognitive beliefs. The MCQ-30 has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.72 to 0.931.

Depressive symptoms

Depression severity was assessed using the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale9, a clinician-administered measure evaluating core depressive symptoms including low mood, anhedonia, sleep disturbance, and psychomotor changes. Scores range from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating greater severity. The HAM-D is a widely used measure with well-established psychometric properties (Cronbach’s α ≈ 0.8), reflecting adequate internal consistency and inter-rater reliability in assessing depression severity. The Beck Depression Inventory-II10 provided a self-report measure of depression severity, with scores ranging from 0 to 63.

Subjective cognitive complaints

The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ;12) assessed self-reported cognitive difficulties in everyday life. This 25-item questionnaire measures the frequency of cognitive failures across memory, attention, and executive functioning. Items are rated on a 5-point scale (0 = “never” to 4 = “very often”), with higher scores indicating more frequent cognitive failures. The CFQ has demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.89) and test–retest reliability (r = 0.82)11.

Objective cognitive performance

Objective cognitive performance was assessed using a comprehensive battery targeting three domains:

-

Verbal memory: The California Verbal Learning Test–II (CVLT-II;11) assessed verbal learning and memory through immediate recall, delayed recall, and recognition trials.

-

Visual memory: The Brief Visuospatial Memory Test–Revised (BVMT-R;13) evaluated visual learning and memory through immediate and delayed recall of geometric figures.

-

Executive functioning: The Trail Making Test (TMT;14) Parts A and B assessed processing speed and cognitive flexibility. The Stroop Color-Word Test15 measured inhibitory control, and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST;16) evaluated set-shifting ability.

Raw scores were converted to age-adjusted standard scores (z-scores). Composite scores for each cognitive domain were calculated by averaging the z-scores of tests within that domain.

Procedure

Participants completed clinical interviews, self-report questionnaires, and cognitive testing in a single session lasting approximately 3 h, with breaks provided as needed. Assessments were administered by trained clinical psychologists or research assistants under supervision. The order of assessment was fixed: clinical interview, self-report measures, and finally cognitive testing. Longitudinal follow-up assessments (6-month and 12-month) followed identical procedures.

Statistical analysis

Network estimation

Network analyses were conducted using R (version 4.1.2) with the packages bootnet (version 1.5;17), qgraph (version 1.9.2;18), and mgm (version 1.2–12;19). To avoid redundancy and multicollinearity, we selected key variables as network nodes: five MCQ-30 subscales, six core HAM-D items (depressed mood, guilt, suicidal ideation, work/activities, psychomotor retardation, psychic anxiety), five CFQ items representing distinct aspects of subjective cognitive complaints, and three composite scores of objective cognitive performance. We tested for any redundant nodes using the “goldbricker” function from the R package networktools. No pair of nodes exceeded the recommended similarity threshold (0.25), indicating that all selected variables captured distinct constructs. We estimated a Gaussian graphical model (GGM) using the graphical least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) algorithm with Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC) model selection. This approach estimates a regularized partial correlation network in which edges (connections between nodes) represent conditional dependence relations between variables, controlling for all other variables in the network. The hyperparameter γ was set to 0.5 to balance sensitivity and specificity. Separate networks were estimated for the full sample, MDD group, and control group.

Network analysis

Network properties were analyzed using several metrics:

-

Centrality indices: strength centrality (sum of absolute edge weights connected to a node), betweenness centrality (number of shortest paths between pairs of nodes that pass through a given node), and closeness centrality (inverse of the sum of distances from a node to all other nodes).

-

Community detection: The walktrap algorithm identified clusters of densely interconnected nodes within the network.

-

Bridge analysis: Bridge expected influence (the sum of edge weights connecting a given node to nodes in other communities) was calculated using the networktools package21 to identify nodes that connect different domains.

-

Network comparison: The Network Comparison Test (NCT;20) evaluated structural differences between the MDD and control networks.

Temporal network analysis

For the longitudinal subsample, we conducted temporal network analysis using graphical vector autoregression (GVAR) models implemented in the mlVAR package18. This approach estimates how variables at one time point predict variables at subsequent time points, controlling for all other variables in the network. Temporal networks were visualized using qgraph, with edges representing significant temporal effects (p < 0.05).

Network stability and accuracy

Network stability was assessed via case-dropping bootstrap procedures (1000 iterations), which yielded correlation stability coefficients for centrality indices (all > 0.25, indicating adequate stability;19). Edge weight accuracy was evaluated using non-parametric bootstrap 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Sample characteristics

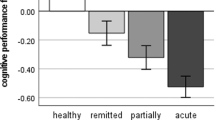

Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of the MDD and control groups. The groups did not differ significantly in age, sex, or education, confirming successful demographic matching. As expected, individuals with MDD scored significantly higher on measures of depression severity, metacognitive beliefs, and subjective cognitive complaints, and demonstrated poorer performance on objective cognitive tests.

Network structure (full sample)

Figure 1 illustrates the network structure for all participants. In the aggregated network, nodes formed coherent communities corresponding to metacognitive beliefs, depressive symptoms, SCCs, and objective cognitive performance. Centrality analysis (Fig. 2) identified negative metacognitive beliefs (strength = 1.87) as the most central node in the overall network, followed by subjective memory complaints (1.62), depressed mood (1.58), and cognitive confidence (1.51). Among metacognitive nodes, negative beliefs about uncontrollability and danger demonstrated substantially higher centrality than other metacognitive dimensions. Objective cognitive performance nodes displayed relatively lower centrality in the overall network. Bridge analysis indicated that negative metacognitive beliefs had the highest bridge expected influence, linking the metacognitive domain with both depressive symptoms and SCCs. Community detection revealed four clusters aligning with the predefined domains (metacognitive beliefs, depressive symptoms, SCCs, and objective cognition).

Network of metacognitive beliefs, depressive symptoms, SCCs, and objective cognitive performance (full sample). Node colors indicate domain (blue = metacognitive, red = depressive, green = SCCs, yellow = objective cognition). Edge thickness reflects the magnitude of regularized partial correlations.

Standardized strength centrality indices for all nodes in the full sample network. Higher values indicate greater centrality. Error bars represent bootstrapped 95% CIs. Node labels correspond to Fig. 1.

Figure 1 Network structure of metacognitive beliefs, depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive complaints, and objective cognitive performance in the full sample. Blue nodes represent metacognitive beliefs (POS = positive beliefs about worry; NEG = negative beliefs about uncontrollability/danger; CC = cognitive confidence; NC = need for control; CSC = cognitive self-consciousness). Red nodes represent depressive symptoms (DM = depressed mood; GF = guilt feelings; SI = suicidal ideation; WA = work/activities; PR = psychomotor retardation; PA = psychic anxiety). Green nodes represent subjective cognitive complaints (MEM = memory failures; ATT = attention failures; ACT = action slips; REC = recognition failures; COM = communication failures). Yellow nodes represent objective cognitive performance (VM = visual memory; VBM = verbal memory; EF = executive function). Edge thickness represents the strength of association; blue edges indicate positive associations, red edges indicate negative associations.

Bridge analysis revealed that negative metacognitive beliefs exhibited the highest bridge expected influence (0.78), forming significant connections between the metacognitive community and both depressive symptoms and subjective cognitive complaints. Cognitive confidence served as a secondary bridge node (0.46), connecting metacognitive beliefs with objective cognitive performance.

Network comparison between MDD and control groups

The Network Comparison Test revealed significant differences in overall network structure (M = 0.28, p = 0.003) and global strength (S = 2.04, p = 0.001) between the MDD and control groups. Figure 3 shows the group-specific networks. In the MDD network, connections between negative metacognitive beliefs and SCCs were notably stronger than in the control network, particularly for memory complaints (edge weight difference = 0.31, p = 0.006) and attention failures (edge weight difference = 0.29, p = 0.008). Additionally, the connection between cognitive confidence and objective visual memory performance was stronger in the MDD group (edge weight difference = 0.24, p = 0.019). Bridge analysis for the MDD network identified negative metacognitive beliefs as the primary bridge between metacognitive beliefs and both depressive symptoms and SCCs (bridge expected influence = 0.84). In contrast, in the control network, cognitive confidence served as the main bridge between metacognitive beliefs and other domains (bridge expected influence = 0.38). Thus, the pattern of interconnections differed qualitatively: the depressed group’s network was characterized by tighter coupling of metacognitive beliefs with mood and subjective cognition, whereas the control group’s network showed weaker cross-domain links.

Network structures for MDD (A) and control (B) groups. Node colors and labels as in Fig. 1. Blue edges indicate positive associations; red edges indicate negative associations. Edge thickness represents association strength.

Temporal network analysis

Temporal network analysis of the longitudinal subsample revealed significant time-lagged relationships between metacognitive beliefs, depressive symptoms, and SCCs across the 12-month follow-up. Figure 4 displays the temporal network with significant pathways. Negative metacognitive beliefs at baseline significantly predicted subsequent depressive symptoms at 6 months (β = 0.34, p < 0.001) and SCCs at 6 months (β = 0.29, p = 0.002), controlling for baseline levels of those variables. Similarly, negative metacognitive beliefs at 6 months predicted depressive symptoms (β = 0.32, p < 0.001) and SCCs (β = 0.27, p = 0.004) at 12 months. Importantly, the reverse temporal paths were considerably weaker and non-significant: neither depressive symptoms nor SCCs at earlier time points significantly predicted later negative metacognitive beliefs (βs < 0.18, ps > 0.09), indicating a primarily unidirectional temporal pattern from metacognitive beliefs to subsequent symptoms/complaints. Objective cognitive performance showed minimal temporal associations with other variables; notably, there were no significant lagged effects between objective performance and either metacognitive beliefs or SCCs.

Temporal network showing significant relationships across time points. Nodes are arranged by domain (metacognitive beliefs, depressive symptoms, SCCs, objective cognitive performance). Arrows represent significant temporal effects (p < .05), and are labeled with standardized β coefficients; arrow thickness indicates effect strength. For clarity, only edges with |β|> 0.20 are displayed.

Discussion and conclusion

This study employed network analysis to investigate the complex interrelationships between metacognitive beliefs, depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive complaints, and objective cognitive performance. Our findings provide several novel insights into the metacognitive underpinnings of depression and cognitive functioning. First, our results demonstrate that negative metacognitive beliefs—particularly beliefs about the uncontrollability and danger of thoughts—were the most central nodes in the network, forming strong connections with both depressive symptoms and subjective cognitive complaints. This aligns with Wells’ metacognitive model of depression1, which posits that negative metacognitive beliefs contribute to the development and maintenance of depressive symptoms by perpetuating rumination and worry. Our study extends this model by showing that these same metacognitive beliefs also contribute to subjective cognitive complaints. Second, the marked discrepancy between the connections of metacognitive beliefs with subjective vs. objective cognitive measures supports the hypothesis that metacognitive beliefs influence the perception and interpretation of cognitive experiences more than actual cognitive performance. This parallels previous findings highlighting the dissociation between subjective and objective cognition in depression11,12. Our results suggest that maladaptive metacognitive beliefs may intensify self-focus and negative interpretive biases, leading to a heightened perception of greater cognitive dysfunction than objectively present. Third, the significant differences in network structure between MDD and control groups underscore the pathological role of metacognitive beliefs in depression. The stronger connections between negative metacognitive beliefs and SCCs in the MDD network suggest that once depression develops, negative metacognitions may play a particularly important role in the subjective experience of cognitive dysfunction. This concurs with the CAS described in the metacognitive model9, wherein perseverative negative thinking and attentional biases increase awareness and negative interpretation of cognitive failures. By contrast, in the control group’s network, negative metacognitive beliefs were not dominant connectors; instead, a different metacognitive factor (cognitive confidence) appeared as a modest bridge between cognitive performance and subjective complaints. This difference reinforces that maladaptive metacognitive influences are especially consequential in the context of depression. Fourth, our temporal network analysis provides evidence consistent with a directional influence of metacognitive beliefs in the relationship between depression and subjective cognitive functioning. The finding that changes in negative metacognitive beliefs predict subsequent changes in both depressive symptoms and SCCs—but not vice versa—supports the metacognitive model’s proposition that these beliefs represent higher-order processes that influence lower-order symptoms and experiences. This temporal sequence suggests that interventions targeting metacognitive beliefs might effectively address both depressive symptoms and subjective cognitive complaints.

These findings have important clinical implications. Metacognitive therapy (MCT;1), which directly targets maladaptive metacognitive beliefs through techniques such as detached mindfulness and attention training, might be particularly effective for addressing not only depressive symptoms but also subjective cognitive complaints. Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of MCT for depression1, but its effects on subjective cognitive functioning have not been systematically evaluated. Our findings suggest that MCT might offer advantages over traditional cognitive-behavioral therapy for depressed patients with prominent subjective cognitive complaints. Furthermore, our results highlight the importance of assessing metacognitive beliefs in the clinical evaluation of cognitive complaints in depression. The MCQ-301 could be incorporated into standard assessment protocols for depressed patients reporting cognitive difficulties, potentially improving treatment selection and prognosis.

Several limitations of the current study warrant consideration. First, while our longitudinal analysis allows for temporal inferences, its limited number of follow-up points (three) constrains the strength of conclusions, and experimental manipulation of metacognitive beliefs would provide stronger evidence for causal relationships. Second, our sample comprised individuals with relatively moderate depression severity and without significant comorbidities, potentially limiting generalizability to more severe or complex clinical presentations. Third, although comprehensive, our cognitive testing battery was administered in a structured setting, which may not fully capture everyday cognitive functioning10. Future research should examine whether metacognitive interventions specifically targeting negative beliefs about uncontrollability and danger of thoughts lead to improvements in both depressive symptoms and subjective cognitive complaints. Additionally, investigating potential moderators of the relationship between metacognitive beliefs and cognitive functioning—such as rumination, personality traits, or attentional control—could provide further insight into underlying mechanisms.

In conclusion, this study provides novel evidence for the central role of metacognitive beliefs in the relationship between depression and subjective cognitive functioning. Our findings support a metacognitive conceptualization of SCCs in depression, whereby maladaptive metacognitive beliefs contribute to a heightened perception and negative interpretation of cognitive difficulties. This metacognitive perspective offers promising avenues for assessment and intervention, potentially addressing a significant unmet need in the treatment of depression-related cognitive dysfunction.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to university’s policy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hammar, Å. & Årdal, G. Cognitive functioning in major depression—a summary. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 3, 26 (2009).

Jones, P. J. (2018). networktools: Tools for identifying important nodes in networks (R package version 1.2.0) [R package]. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=networktools.

Haslbeck, J. M. B. & Waldorp, L. J. mgm: Estimating time-varying mixed graphical models in high-dimensional data. J. Stat. Softw. 93(8), 1–46 (2020).

Heaton, R. K., Chelune, G. J., Talley, J. L., Kay, G. G., & Curtiss, G. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test: Manual—Revised and Expanded. (Psychological Assessment Resources, Lutz, FL, 1993).

Koster, E. H. W., De Lissnyder, E., Derakshan, N. & De Raedt, R. Understanding depressive rumination from a cognitive science perspective: The impaired disengagement hypothesis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31(1), 138–145 (2011).

Normann, N., van Emmerik, A. A. P. & Morina, N. The efficacy of metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Depress. Anxiety 31(5), 402–411 (2014).

Papageorgiou, C. & Wells, A. An empirical test of a clinical metacognitive model of rumination and depression. Cogn. Ther. Res. 27(3), 261–273 (2003).

Reitan, R. M. Validity of the trail making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept. Mot. Skills 8(3), 271–276 (1958).

Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 23(1), 56–62 (1960).

Groenman, A. P., van der Werf, S. & Geurts, H. M. Subjective cognition in adults with common psychiatric classifications: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 313, 114374 (2022).

Fried, E. I. et al. Mental disorders as networks of problems: A review of recent insights. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 52(1), 1–10 (2017).

Golden, C. J. Stroop Color and Word Test: A Manual for Clinical and Experimental Uses. (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL, 1978).

Flavell, J. H. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. Am. Psychol. 34(10), 906–911 (1979).

First, M. B., Williams, J. B. W., Karg, R. S., & Spitzer, R. L. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5—Research Version (SCID-5-RV). (American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington, VA, 2015).

Delis, D. C., Kramer, J. H., Kaplan, E. & Ober, B. A. California Verbal Learning Test–Second Edition: Administration and Scoring Manual 2nd edn. (Psychological Corporatio, San Antonio, TX, 2000).

Broadbent, D. E., Cooper, P. F., FitzGerald, P. & Parkes, K. R. The cognitive failures questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 21(1), 1–16 (1982).

Brigola, A. G. et al. Subjective memory complaints associated with depression and cognitive impairment in the elderly: A systematic review. Dementia & Neuropsychologia 9(1), 51–57 (2015).

Bridger, R. S., Johnsen, S. Å. K. & Brasher, K. Psychometric properties of the cognitive failures questionnaire. Ergonomics 56(10), 1515–1524 (2013).

Borsboom, D. & Cramer, A. O. J. Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9(1), 91–121 (2013).

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory–II 2nd ed. (Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX, 1996).

Benedict, R. H. B. Brief Visuospatial Memory Test–Revised: Professional Manual. (Psychological Assessment Resources, Lutz, FL, 1997).

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study has been reviewed by the University Review Committee (U.R.C.) including Human Subjects for the School at Shandong First Medical University, Shandong Province, China, who verified that all methods used in this study were carried out in line with the 1964 Helsinki 10 declaration and its subsequent revisions or similar ethical standards, as well as the ethical requirements of the institutional research committee. Informed consent has been obtained from all subjects involved in this study to publish this paper.

Consent for publication

We agree to access my manuscript for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhan, Y., Ding, X. Metacognitive deficits drive depression through a network of subjective and objective cognitive functions. Sci Rep 15, 22529 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06224-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06224-1