Abstract

The association between various diseases in the elderly and self-rated health (SRH) has been investigated in many prior studies. Our study aimed to investigate the relationship between oral health and SRH among the geriatric Indian population. The current study used data from the Longitudinal Study of Ageing in India (LASI), conducted during 2017–2018. Our research included 31,228 individuals aged ≥ 60 in the LASI analysis. The present study used univariate and bivariate analyses, including the chi-square test, binary logistic regression, and propensity matching score to accomplish the research objectives. Nearly 88% of the elderly population were exposed to poor oral health status. One-fourth of the older people had poor SRH. The elderly with poor oral health status had a higher prevalence of SRH compared to their counterparts. Propensity score matching (PSM) also showed that the likelihood of experiencing poor SRH exceeded by 5% points among the elderly with poor oral health compared to their counterparts. Our study’s results demonstrated a higher prevalence of oral morbidities among the Indian elderly. It also established a significant and robust association of poor oral health status with poor SRH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Population ageing is a continuous demographic change characterized by rising life expectancy and diminishing birth rates1. There is an increasing focus on the ageing population in developing and developed nations. The United Nations notes that the population aged 65 and above was 703 million in 2020, and is predicted to rise to 1.5 billion by 20502. India is also witnessing demographic transformation, with the senior population anticipated to increase from 8.6% in 2011 to nearly 20% by 2050. By 2026, this population is predicted to exceed 173 million, due to marked improvement in health care3,4,5. While an increased life expectancy is often seen as a positive development, it also presents obstacles associated with age-related illnesses and impairments.

Amidst these concerns, oral health is a crucial yet underemphasized aspect of well-being among the elderly. Ageing impacts over 280 million elderly worldwide, but dental issues like, dental caries, gingival infections, and periodontal conditions are overlooked in national health strategies for elderly population6,7. In India, over 75% of the population has oral health issues, which are associated with poor nutrition, frailty and disability8. These health issues often coexist with other chronic diseases and lead to multi-morbidity and worsening of self rated health (SRH)9,10. Dental issues can result in difficulty in mastication that pre-disposes to dietary restriction, systemic inflammation, and psychological effects6,9,10. These sequelae result in frailty, disability and a negative self-assessment of health6,7.

The “Expansion of Morbidity” hypothesis states that although people are living longer, many of them are experiencing these additional years with chronic diseases and functional impairment11,12. In the elderly population, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and chronic diseases are higher than in their younger counterparts13,14. Depression and hypertension are the most prevalent global health problems and are the precursors of cardiovascular diseases. These account for about 7% of Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs)15. Recent literature reveals that 40% of the geriatric population in India have hypertension while 3.3% have depressive disorders16. Depression is a leading mental illness that is prevalent with age; and affects more than 45 million Indians, which impacting DALYs17,18.

These chronic conditions tend to coexist and result in functional limitation, poor quality of life and increased utilisation of health care services. Multimorbidity is marked by an individual having two or more chronic diseases19,20. The trend of multimorbidity adversely affects the health conditions and well-being of the elderly in particular21. Notably in low and middle-income populations when people live longer, they are exposed to factors that contribute to the onset of chronic diseases11. Research in Bangladesh and India, two South Asian nations reveal significant variation in multimorbidity prevalence, ranging from 4.5 to 83%22,23. Almost one-third of Indian elderly are affected by multimorbidity, linked with poor physical and mental functioning and results in a poorer quality of life24. This worrying trend calls for early intervention to enhance the well-being of the elderly.

SRH has emerged as an important tool in capturing the health conations among the elderly. SRH is a widely used indicator25 to indicate how people perceive their health. This is an aggregated measure that incorporates both the physical and psychological well-being of the individual and is influenced by sociodemographic and behavioral factors. Research from the United States and France has shown that SRH is negatively affected by lower scores, constraints in daily activities, chronic conditions, and memory issues. In India, a study by Sheikh et al. (2024)26 identified lifestyle behaviours as important pathways to SRH. Saha et al. (2022)27 pointed out that the health status of elderly is influenced by living arrangements, marital status and geographical area (urban/rural). The relationship between SRH and geriatric conditions has been studied extensively in India and other countries. Numerous studies have established causal links between health outcomes and exposure i.e. substance use, physical activity and socioeconomic status28,29,30. Saha (2024)31 investigated the association between engagement in social activities and the physical and mental wellness status of old individuals in India, contributing significantly to the understanding of health outcomes within this population.

Despite the growing concern of multimorbidity, oral health remains a blind spot in the study of chronic health conditions among the geriatric population6,14. Studies have focused predominantly on cancer, cardiac disease, hypertension, stroke, thyroid disorders, diabetes, dyslipidemia, chronic lung disease, arthritis, depression, and angina, overlooking the impact of oral health in promoting healthy ageing18,22,24.

Studies that highlight the role of oral health in shaping SRH, especially in the Indian setting are limited23,24. A few previous studies, such as those conducted by Ghosal et al. (2022)32 and Batra et al. (2020)10, have mainly investigated the status and patterns of oral health problems and their associations. Literature reveals that oral morbidity increases the chance of poor SRH in the elderly7,8. However, the causal association through which oral morbidity is linked to SRH remains hitherto unexplored in the Indian context33. Poor oral health can hinder the control of NCDs leading to a vicious cycle in the elderly34,35. However, research in the Indian subcontinent lacks sufficient evidence to understand the mechanisms underlying the mentioned association. Our study aims examine the relationship between oral health and SRH using the LASI data to address this contentious issue. The research question for this study is whether oral morbidity affects the SRH of the elderly in India.

Materials and methods

Data source

This research used Wave 1 (2017–2018) of the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI). It is a nationally representative survey of ageing and health in India. The LASI surveyed 73,396 people aged ≥ 45 from the entire country. The dataset contains 31,902 subjects aged 60 and above. LASI offers a rich source of information on different aspects of health, healthcare utilization, sociodemographic characteristics, disease burden, and program and policy coverage among the older population. The survey applied a stratified random cluster sampling strategy including several stages. A three-stage sampling method i.e. selection of Primary Sampling Units (villages), selection of households and selection of individuals was used in the rural regions. In urban areas, a four-stage sampling approach i.e. selection of wards, selection of Census Enumeration Blocks, selection of households and selection of eligible individuals was used. The household and individual response rates were approximately 93% and 96% respectively. More details on the sampling procedures are described in the LASI national report 2017–201836.

Study sample

The first LASI Wave included a total of 73,396 people aged ≥ 45. This research only analyzed Indian individuals aged 60 years and above. After excluding respondents aged 59 or below (n = 41,494), and those who did not provide information on their SRH (n = 674), the final analysis was conducted on 31,228 older people. This study focuses on the impact of oral morbidity and self-rated health among the elderly in India. Prior evidence shows that the severity of oral health issues such as gingival disease and tooth loss, and their functional impact are much more prominent among the elderly6,31. Our study did not compare younger and older individuals. Therefore, to maintain conceptual clarity, the study only considered the population aged 60 years and above. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of selecting the study population.

Variable description

Outcome variable

Self-rated health (SRH) was assessed in the LASI individual schedule with the question: “Overall, how would you rate your health in general?” The responses included: “Very good,” “Good,” “Fair,” “Poor,” and “Very poor.” The respondents who had at least one of the specified oral health problems were considered to have “poor” oral health. In this study, SRH was classified as a binary variable. Those who selected the categories ‘Poor’ and ‘Very poor’ were classified as having poor health (coded as 1), while the categories ‘Fair’, ‘Very good’, and ‘Good’ were classified as having good health (coded as 0)4.

Exposure variable

Oral health

The LASI survey has information on oral health problems in the past year, which includes periodontal diseases (swelling or bleeding of the gums, ulcers), dental caries, tooth pain, loose teeth, cavities, sores or cracks in the corners of the mouth, tooth loss (edentulism) and problems in chewing solids. In this study, swollen gums, dental caries, bleeding gums, tooth pain, ulcers (more than two weeks), loosed teeth, and comfortably sores/cracks in the corners of the mouth were also considered as relevant parameters. Nevertheless, several characteristics, including regular visits to the dentist, ability to chew solid food, and gum disease were not included due to their possible correlation with the aforementioned conditions. The variables included are; Any of these conditions were classified as 1 (Poor oral health), while the variables that were not present were considered as 0 (Good oral health).

Covariates

The covariates included several characteristics such as gender (Male and Female), age (60–69, 70–79, and 80 and above), education (attended school and never attended), and marital status (married and others). The study also considered other factors such as religion (Hindu, Muslim, and Others), place of residence (rural and urban), Monthly Per Capita Expenditure (MPCE) quintile (Poorest, Poorer, Middle, Richer, and Richest), and caste (Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe, Other Backward Class, and Others) together with living arrangements (living alone, living with spouse and or other, living with spouse and children, living with children and other, or living with others only). Three lifestyle factors were also considered: Current tobacco use (Yes or No), Current alcohol use (Yes or No), and Physical activity (Yes or No).

The association between oral morbidity and outcome variables, namely SRH and hypertension is depicted in Fig. 2.

Statistical analysis

In this study, descriptive, bivariate, binary logistic regression model were conducted. Frequencies and percentages were among the descriptive statistics utilized to characterize the study population. Chi-square test (χ2) was performed to compare the prevalence of SRH across the covariates and oral health. We applied the svyset command to account for the complex survey design, and employed individual-level sample weight available in the dataset to ensure the representativeness of the estimates. Propensity score matching (PSM) was conducted to accomplish the objectives. A p-value below 0.05 was taken as significant in all analyses. The regression with multiple models was used to assess the relationship between oral health, other covariates, and SRH. Then, the effect of oral health on SRH was examined again after controlling for all the covariates. The following models were estimated:

Model 1

Oral Health and SRH.

Model 2

Oral Health + Individual and Household Characteristics and SRH.

Model 3

Oral Health + Individual and Household Characteristics + Lifestyle Factors and SRH.

A multicollinearity test was conducted using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and the result showed that there was no multicollinearity among the variables (Mean VIF = 1.3, Max VIF = 1.65, Min VIF = 1.01). The Stata version 16 was used to complete the study analysis.

Propensity score matching (PSM) was applied to analyze the relationship between oral health and self-rated health (SRH). The LASI is based on probability sampling, but selection bias may still occur in observational analysis because of differences in covariates across exposure groups. The propensity score was used to reduce such bias by balancing observed characteristics between individuals with and without poor oral health37. This method produces a counterfactual to enable the estimation of the effect of the treatment (poor oral health in this case) when it did not occur.

In PSM, the propensity score is computed based on many variables that ascertain the likelihood of an individual being allocated to the treatment group. The propensity score was used to implement kernel matching to equilibrate the sample between the treatment and control groups. The propensity score is a balancing measure that ensures t the equilibrium of observable features between the two groups. In this study, the persons with poor oral health were considered as the treatment group. The Kernel-based matching was done to compare them with the elderly having good oral health (control group). The weights were assigned to all control observations in accordance with their proximity in propensity score space. This allows for the e utilization of more information from the sample and provides more stable estimates than strict one-to-one matching. The PSMs were calculated based on several selected variables such as individual, household, and lifestyle factors.

The probability that oral health affects SRH given definite variables can be written as:

Where D = 0 if the person has good oral health.

D = 1 if the person has poor oral health.

And X is the vector of pre-intervention characteristics.

To measure the effect of oral health on SRH, two parameters were calculated: Average Treatment Effect (ATE) and Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT).

i. Average Treatment Effect (ATE): This parameter measures the average effect of poor oral health on the population and can be written as:

Where:

E(.) is the mathematical expectation.

Y1Y_1Y1 represents average SRH outcome for individuals with poor oral health.

Y0Y_0Y0 represents average SRH outcome for those with good oral health.

ii. Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT): ATT is the mean treatment effect for those who were indeed treated (that is, had poor oral health). It is defined as:

where (D) = (0, 1) denotes the control and treatment group, respectively. Where \({\text E}({\text Y0} \mid {\text D }= 1)\) is a counterfactual mean, it is the expected mean of the treated subjects, which would have experienced if they had good oral health. Since this is unobservable it has to be estimated using the matching technique.

Ethical consideration

The research used publicly available data from the IIPS LASI portal. Since the data were publicly accessible and de-identified, no additional ethical approval was required.

Results

Profile of the study population

Table 1 shows the selected background characteristics of 31,228 elderly in India. The predominant segment of the sample population (59.4%) consisted of individuals aged 60 to 69. Women made up a slightly higher proportion of the sample (52.7%) compared to men (47.3%). A significant portion of the population (56.5%) had no formal education, while over 70% of the sample resided in rural areas, Economic inequalities were apparent, with 43.4% of respondents falling into the two lowest MPCE quintiles (poorest and poorer), while only 16.5% were in the richest quintile. Nearly 6% of the elderly reported living alone at the time of the survey. As far as lifestyle behaviours are concerned, approximately one-third of the elderly population were current smokers, while 7.8% reported consuming alcohol within the past three months.

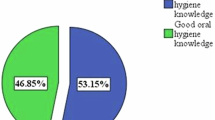

The health profile of older adults highlights significant concerns, with an overwhelming majority (88.3%) reporting poor oral health and nearly one-fourth (24.2%) reporting poor self-rated health.

Prevalence of self-rated health (SRH) based on oral health status and other factors

Table 2 illustrates the prevalence of poor SRH based on oral health status and other chosen factors among elderly individuals in India. The prevalence of poor SRH was greater among the elderly with inadequate oral health (25.1%) than those with satisfactory oral health (17.7%) (Fig. 3), with a χ2 test value of < 0.001, indicating a robust association between oral health and SRH.

The prevalence of poor SRH rose with age. Among those aged 60–69 years, 20.3% reported poor SRH, which rose to 27.4% for those aged 70–79 years, and peaked at 36.6% for those aged 80 years and older. A larger proportion of females (25.9%) reported poor SRH compared to males (22.3%). Older adults who never attended school had a higher prevalence of poor SRH (26.5%) compared to those who attended school (21.2%). Poorer individuals in the lowest MPCE quintiles (poorest and poorer) reported higher levels of poor SRH (26.4% and 24.1%, respectively), compared to those in the richer quintiles. Older persons living alone were more vulnerable to poor self-rated health (35.1%), followed by those living with others only (31.9%).

As far as lifestyle behaviours are concerned, tobacco consumers had a slightly lower prevalence of poor SRH (22.6%) compared to non-smokers (25.0%). Alcohol consumers in the past three months also reported a lower prevalence of poor SRH (18.9%) than non-consumers (24.7%). A notable difference was observed between those who engaged in physical activities (21.0%) and those who did not (29.5%). The result also highlights that oral health, along with all other covariates except place of residence, is significantly linked with poor SRH among the elderly.

Oral health status and SRH

Table 3 depicts the association between oral health conditions and SRH, using multiple binary logistic regression. Three models were employed to explore this relationship; Model 1 (unadjusted analysis), Model 2 (after adjusting for individual and household factors) and Model 3 (after further adjusting for lifestyle factors). In Model 1, the results found that elderly with poor oral health status had a 75% (UOR: 1.75; 95% CI: 1.42–2.15) higher likelihood of experiencing poor SRH than their counterparts. In Model 2 & 3, the association between oral health and poor SRH remained statistically significant. The odds ratios were 1.59 (95% CI: 1.40–1.75) in Model 3 and 1.57 (95% CI: 1.42–1.72) in Model 2. The Odds ratios indicate that poor oral health is significantly linked with a higher chance of experiencing poor SRH among elderly, even after accounting for potential confounders.

Association between covariates and SRH

Age and sex emerged as significant predictors, with higher odds of poor SRH observed among females and older age groups (e.g., adults aged 80 + years had nearly double the odds: AOR: 1.97; 95% CI:1.81–2.16) (Table 3). Caste, religion, living arrangements, and physical activity were also significant covariates; for instance, Scheduled Tribe individuals and those living with children or others reported better SRH, while those not participating in physical activity had 49% higher odds of poor SRH (AOR: 1.49; 95% CI:1.41–1.58). Muslims had significantly higher odds of reporting poor self-rated health than Hindus (AOR: 1.23; 95% CI:1.13–1.34). Economic status showed limited association with poor SRH, while tobacco consumption and alcohol use were not statistically related to poor SRH among older elderly in the adjusted models.

Propensity score matching (PSM) results

Figure 4, a balance diagnostic using kernel density, typically illustrates the propensity score distribution for both the treatment and control groups before and after matching. Before matching, the kernel density curves for the treatment group (e.g., individuals with poor oral health) and the control group (e.g., individuals with good oral health) are showed a substantial change in the range of scores, indicating an imbalance in covariates between the groups. After matching, the kernel density curves for the treatment and control groups coincided more closely, demonstrating improved balance in covariate distribution achieved through matching. This overlap indicates that the matched samples are more comparable, reducing selection bias in estimating the treatment impact of oral health status on poor SRH.

Estimating the effect of oral morbidity on SRH outcomes

The results from PSM analysis, presented in Table 4, demonstrate the contribution of oral health status to poor SRH among the Indian elderly. Before matching, the proportion of people with poor SRH was 0.09 higher among those with poor oral health (treated) than those with good oral health (controls); 24% vs. 15%. After matching, this difference was reduced to 0.05 (24% vs. 19%), which means that poor oral health remains significantly associated with poor SRH even when other potential confounders are assessed. The ATE of poor oral health on SRH was estimated at 0.05, with a statistically significant at p < 0.001 (95% CI: 0.04, 0.07). These findings depict that poor oral health is an important contributor to SRH among older adults, even after consideration of selection bias through matching.

Discussion

Global demographic shifts are ubiquitous, indicated by ageing populations, which frequently correspond with rising illness, especially in emerging nations like India14. As a result, ageing has become a major concern, and healthy ageing is an important public health goal. The role of oral health in shaping SRH remains inadequately explored, especially within the Indian context33. This paper aspires to fill this gap by examining the repercussions of oral health on SRH among the elderly using nationally representative data from LASI. It determines the prevalence of suboptimal self-rated health and its underlying causes. It employs robust multivariate logistic regression and PSM in a bid to eliminate bias.

Our analysis noted a higher prevalence of oral morbidities was experienced by the elderly in India; 88% of them had problems like dental caries, periodontal disease and tooth loss. This prevalence is higher than what has been documented in earlier researches14. A paper from New Delhi indicated that 92% of those over 60 years had dental caries38. The factors contributing to these problems include improper dietary practices, limited access to dental services, inadequate oral hygiene, and drug misuse9,23,31. Another study indicated that oral health is inadequately regarded within the broader health framework, leading to the chronicity of oral disorders due to neglect39. It demonstrated that about 25% of elderly in India had poor SRH27,29. A number of factors, including age, sex, religion, living arrangements, and daily activities, were seen to be associated with poor SRH40. The extreme elderly were more likely to report SRH than young-old (60–69 years). This finding is in concordance with previous studies that have similarly shown a greater burden of SRH among the oldest elderly31,41. This difference is mainly explained by the fact that physiological deterioration increases with age and leads to decreasing physical and functional status, social isolation, and limited accessibility to health care, which in turn hampers the SRH23. Furthermore, females were 30% more inclined to assess their health as fair or poor compared to men42. This increased sensitivity could be attributed to their dependent status on physical and financial aspects of spouses and/or children, which in turn limits their ability to acquire desired health care treatments23,43.

Our study is in concordance with contemporary literature that elderly people who are lonely and those who do not exercise have a stronger inclination to assess their poor health; this may be due to social isolation, loneliness, and multimorbidity29,44,45. The results of our study noted that Muslims were at greater risk of having poor SRH, which may be due to socioeconomic status, healthcare availability, and cultural factors46. It is pertinent that in the final model, substance use and housing location surprisingly did not significantly correlate with SRH.

A major finding of the study is that poor oral health is a strong exposure of poor SRH among older adults, even after adjusting for individual, household, and lifestyle factors7. The condition of oral health affects SRH through ongoing physical discomfort, nutritional limitations, and psychosocial distress that extend beyond the effects of individual, household, and lifestyle factors8,31. The PSM analysis results supported this association. It was established that older adults with poor oral health were 1.6 times more likely to have in poor SRH. The PSM analysis showed a post-matching difference of 0.05 (24% vs. 19%), which means that poor oral health remains a significant exposure for poor SRH even when other potential confounders are considered.

An Algerian study showed that poor SROH is a key contributor to SRH which is similar to our study47. Sanabria (2023)48 in Colombia also established that overall edentulism and dental implants utilisation are significant predictors of SRH. Researchers have argued that oral health complications such as edentulism, gum disease, and poor dental cleanliness are linked with other diseases like diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and depression that affect SRH8,9,49.

It has been established that the inflammatory burden that is associated with poor oral health increases the risk of chronic diseases and subsequently decreases the perceived health status50. Dental pain, tooth loss, and issues with mastication are also connected with malnutrition thereby worsening overall health status and SRH38,51. Stigma, in the form of embarrassment over dental appearance and social isolation due to oral discomfort, affects self-esteem and SRH outcome52. Literature indicates that older people with oral health problems tend to rate their general health and mental well-being inferior due to the impact of poor dental health on nutrition, speech, and social interaction53. In India, poor oral health is exacerbated by poor diet, improper brushing techniques and inadequate availability of dental services10,54. Since oral health is usually not considered as much as other health concerns, dental diseases tend to become chronic and cause systemic issues32. The study has important implications for healthcare delivery systems and public health policies in LMICs, including India, which is experiencing fast population ageing. Oral health is often neglected in national programs such as the National Programme for Health Care of the Elderly (NPHCE) despite its well-established associations with health and nutrition outcomes. The research demonstrates the necessity of including oral health services to standard geriatric care in India. Combining community-based dental care with frontline health worker training can address the service gaps. Oral health must be recognized as pivotal in maintaining healthy aging and overall quality of life.

Limitations

Our analysis undertakes a comprehensive assessment of oral health and SRH in the geriatric population, utilizing extensive national data sets from India. It offers a valuable perspective on this unexplored domain. Despite its strength, our study is not without limitations. Firstly, the study relied on cross-sectional data, which restricts the establishment of a causal link between the exposure (oral health) and the results (SRH). Secondly, the study neither considers the nutritional factors nor the factors related to oral health, such as oral hygiene and proximity to dental care, due to the lacunae of data in the survey, and these factors have a role in influencing health outcomes. Thirdly, the SRH is a subjective concept that depends upon the respondent’s perceptions, and can introduce bias. These limitations highlight the demand for comprehensive prospective research examining the variables influencing oral health outcomes.

Conclusion

Our research demonstrates a robust linkage between oral health status and poor self-rated health (SRH) in the Indian subcontinent. An overwhelming part of the geriatric population suffered from dental issues. The results underscore that oral health is a vital aspect of healthy ageing. Neglect towards dental health results in chronic systemic sequelae. The study recommends that policymakers prioritize oral healthcare in the health policy, strategies, and programs directed at older persons. In addition, it is prudent to incorporate appropriate oral hygiene habits and regular dental examinations in programs for the geriatric population.

Data availability

The data used for this study is publicly available. Anyone can download the LASI data set from the International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) website (https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/content/LASI-data).

References

World Health Organization. Progress report on the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing, 2021–2023. at (2023). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240079694

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Ageing 2023: Challenges and opportunities of population ageing in the least developed countries. at (2023). https://desapublications.un.org/publications/world-population-ageing-2023-challenges-and-opportunities-population-ageing-least

Agarwal, A., Lubet, A., Mitgang, E., Mohanty, S. & Bloom, D. E. in Popul. Change Impacts Asia Pac. (eds. Poot, J. & Roskruge, M.) 30, 289–311Springer Singapore, (2020).

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) & National Programme for Health Care of Elderly (NPHCE), MoHFW. Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) Wave 1, 2017-18, India Factsheet, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai. (International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and NPHCE, MoHFW. at (2018). https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/sites/default/files/other_files/LASI_W1_Factsheet_INDIA.pdf

United Nations Population Fund. ‘Caring for Our Elders: Early Responses’ - India Ageing Report – 2017. UNFPA, New Delhi, India. at (2017). https://india.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/India%20Ageing%20Report%20-%202017%20%28Final%20Version%29.pdf

Chan, A. K. Y., Chu, C. H., Ogawa, H. & Lai, E. H.-H. Improving oral health of older adults for healthy ageing. J. Dent. Sci. 19, 1–7 (2024).

Peres, M. A. et al. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet Lond. Engl. 394, 249–260 (2019).

Roy, S., Malik, M. & Basu, S. Prevalence, patterns, and predictors of oral morbidity in patients with diabetes: evidence from the longitudinal ageing study in India. Cureus 16, e72164 (2024).

Mehta, V. et al. Oral health status of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities in india: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 24, 748 (2024).

Batra, P., Saini, P. & Yadav, V. Oral health concerns in India. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 10, 171–174 (2020).

Geyer, S. & Eberhard, S. Compression and expansion of Morbidity—Secular trends among cohorts of the same age. Dtsch. Arzteblatt Int. 119, 810–815 (2022).

Gruenberg, E. M. The failures of success. Milbank Mem. Fund Q. Health Soc. 55, 3–24 (1977).

Jan, B. et al. Cardiovascular Diseases Among Indian Older Adults: A Comprehensive Review. Cardiovasc. Ther. 6894693 (2024). (2024).

Patel, V. et al. The lancet commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet Lond. Engl. 392, 1553–1598 (2018).

GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Lond. Engl. 403, 2133–2161 (2024).

Aggarwal, P. & Raval, V. V. Examining concurrent and longitudinal associations between quality of interpersonal relations and depressive symptoms among young adults in India. J. Affect. Disord Rep. 19, 100851 (2025).

Kundu, A. & Bandyopadhyay, S. in Dev. Environ. Sci. (eds. Sivaramakrishnan, L., Dahiya, B., Sharma, M., Mookherjee, S. & Karmakar, R.) 14, 415–430 (Elsevier, 2024).

Panda, P., Dash, P., Behera, M. & Mishra, T. Prevalence of depression among elderly women in India-An intersectional analysis of the longitudinal ageing study in India (LASI), 2017–2018. Res. Sq. rs.3.rs-2664462 (2023).

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global burden of disease study 2019. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. at (2020). https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019

Hajat, C. & Stein, E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: A narrative review. Prev. Med. Rep. 12, 284–293 (2018).

García Pérez, A. & Villanueva Gutiérrez, T. Multimorbidity and depressive symptoms and their association with Self-Reported health and life satisfaction among adults aged ≥ 50 years in Mexico. J. Cross-Cult Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-025-09521-4 (2025).

Chowdhury, S. R., Das, C., Sunna, D., Beyene, T. C., Hossain, A. & J. & Global and regional prevalence of Multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 57, 101860 (2023).

Pati, S. et al. Prevalence and outcomes of Multimorbidity in South asia: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 5, e007235 (2015).

Varanasi, R. et al. Epidemiology and impact of chronic disease Multimorbidity in india: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Multimorb Comorbidity. 14, 26335565241258851 (2024).

World Health Organization. Decade of healthy ageing: baseline report. at (2021). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017900

Sheikh, I., Garg, M. K., Agarwal, M., Chowdhury, P. & Saha, M. K. Functional limitations and depressive symptoms among older people in india: examining the role of physical activity. Int. J. Ment Health Addict. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01250-y (2024).

Saha, A., Rahaman, M., Mandal, B., Biswas, S. & Govil, D. Rural urban differences in self-rated health among older adults: examining the role of marital status and living arrangements. BMC Public. Health. 22, 2175 (2022).

Prieto, L. Exploring the influence of social class and sex on Self-Reported health: insights from a representative Population-Based study. Life Basel Switz. 14, 184 (2024).

Basumatary, R., Kalita, S. & Bharadwaj, H. Self-rated health of the older adults in the Northeastern region of india: extent and determinants. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob Health. 30, 101856 (2024).

Rarajam Rao, A. et al. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Impairment in Intrinsic Capacity among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: An Observational Study from South India. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 1–9 (2023). (2023).

Saha, S. Social relationships and subjective wellbeing of the older adults in india: the moderating role of gender. BMC Geriatr. 24, 142 (2024).

Ghosal, S. et al. Oral health among adults aged ≥ 45 years in india: exploring prevalence, correlates and patterns of oral morbidity from LASI wave-1. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob Health. 18, 101177 (2022).

Kanungo, S. et al. Association of oral health with Multimorbidity among older adults: findings from the longitudinal ageing study in india, Wave-1, 2017–2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 12853 (2021).

Badewy, R., Singh, H., Quiñonez, C. & Singhal, S. Impact of poor oral health on Community-Dwelling seniors: A scoping review. Health Serv. Insights. 14, 1178632921989734 (2021).

Wolf, T. G., Cagetti, M. G., Fisher, J. M., Seeberger, G. K. & Campus, G. Non-communicable diseases and oral health: an overview. Front. Oral Health. 2, 725460 (2021).

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), National Programme for Health, MoHFW Care of Elderly (NPHCE), Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health (HSPH), & University of Southern California (USC). Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) Wave 1, 2017-18, India Report, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai. at (2020). https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/sites/default/files/LASI_India_Report_2020_compressed.pdf

Rosenbaum, P. R. & Rubin, D. B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. (1983).

Patro, B. K., Kumar, R., Goswami, B., Mathur, A., Nongkynrih, B. & V. P. & Prevalence of dental caries among adults and elderly in an urban resettlement colony of new Delhi. Indian J. Dent. Res. Off Publ Indian Soc. Dent. Res. 19, 95–98 (2008).

Watt, R. G. et al. Ending the neglect of global oral health: time for radical action. Lancet Lond. Engl. 394, 261–272 (2019).

Patnaik, I., Sane, R., Shah, A. & Subramanian, S. V. Distribution of self-reported health in india: the role of income and geography. PloS One. 18, e0279999 (2023).

Xu, D., Arling, G. & Wang, K. A cross-sectional study of self-rated health among older adults: a comparison of China and the united States. BMJ Open. 9, e027895 (2019).

Arokiasamy, P., Jain, K., Multi-Morbidity & Uttamacharya & Functional limitations, and Self-Rated health among older adults in india: Cross-Sectional analysis of LASI pilot survey, 2010. Sage Open. 5, 2158244015571640 (2015).

Singh, K. et al. Multimorbidity in South Asian adults: prevalence, risk factors and mortality. J. Public. Health Oxf. Engl. 41, 80–89 (2019).

Yang, M. & Gong, S. Geographical characteristics and influencing factors of the health level of older adults in the Yangtze river economic belt, china, from 2010 to 2020. PloS One. 19, e0308003 (2024).

Patel, R. & Bansod, D. W. Correlates of poor self-rated health among school-going adolescent girls in urban varanasi, India. BMC Public. Health. 23, 1921 (2023).

Chowdhury, S. H. et al. Risk of depression among Bangladeshi type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 11 (Suppl 2), S1009–S1012 (2017).

Pengpid, S. & Peltzer, K. Poor Self-Rated oral health status and associated factors amongst adults in Algeria. Int. Dent. J. 73, 701–708 (2023).

Venegas-Sanabria, L. C., Moreno-Echeverry, M. M., Borda, M. G., Chavarro-Carvajal, D. A. & Cano-Gutierrez, C. A. Oral health and self-rated health in community-dwelling older adults in Colombia. BMC Oral Health. 23, 772 (2023).

Moynihan, P., Makino, Y., Petersen, P. E. & Ogawa, H. Implications of WHO guideline on sugars for dental health professionals. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 46, 1–7 (2018).

Wu, B., Fillenbaum, G. G., Plassman, B. L. & Guo, L. Association between oral health and cognitive status: A systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 64, 739–751 (2016).

Inoue, S., Suma, S., Furuta, M., Wada, N. & Yamashita, Y. Possible association between oral health status and appetite loss in community-dwelling older adults. Nurs. Health Sci. 26, e13111 (2024).

Jacob, L. et al. Associations between mental and oral health in spain: a cross-sectional study of more than 23,000 people aged 15 years and over. J. Affect. Disord. 274, 67–72 (2020).

Shankar, K. S. et al. Effectiveness of oral health education interventions using braille on oral health among visually impaired children: proposal for a systematic review. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 16, S97–S101 (2024).

Kothia, N. R. et al. Assessment of the status of National oral health policy in India. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 4, 575–581 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.M., I.S., A.M. - conception or design of the work; T.N., I.S. - analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; V.M., I.S. - drafted the work; I.S., T.N., A.M. - reviewed it critically for important intellectual content. All the authors gave their approval for the final version to be published and are in agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheikh, I., Mehta, V., Noor, T. et al. Assessment of oral morbidity and self rated health in the Indian geriatric population with a propensity score matched approach. Sci Rep 15, 33045 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06287-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06287-0