Abstract

The incidence of infertility in the world is gradually increasing, and assisted reproductive treatment is one of the main methods for infertility treatment worldwide. Infertile women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment are likely to have a negative psychological state. However, deficits in the existing knowledge about women’s negative psychological conditions greatly limit the implementation and effectiveness of psychological interventions. The aim of this study was to identify the specific risk factors for a negative psychological state in infertile women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment. A mixed-methods design that combined quantitative survey and qualitative interview was adopted in this study. In the quantitative study, the DASS-21 questionnaire was administered on 437 infertile women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment to evaluate the prevalence of negative psychological symptoms. Descriptive statistics were conducted on the participants’ demographic information and clinical data, and multiple linear regression analysis was performed on the quantitative data to determine the risk factors for negative psychological states. In the qualitative study, semistructured interviews were conducted with 14 women who reported negative psychological symptoms in the quantitative survey. Thematic analysis was employed for qualitative data. The results of quantitative and qualitative study were comprehensively analyzed and classified. The results of the quantitative survey suggested a high prevalence of anxiety (24.3%), depression (10.8%) and stress (8.7%). Univariate analysis revealed that a negative psychological state in infertile women is significantly related to occupation type, household income, infertility factors, duration of infertility treatment, and the number of previous assisted reproductive treatment cycles (P < 0.05). Multivariate linear regression analysis indicated that annual per capita household income was the primary factor influencing depression scores (P < 0.05), the duration of infertility treatment and occupation type were the primary factors influencing anxiety scores (P < 0.05), unexplained infertility was the primary factor influencing stress scores (P < 0.05). Subsequent qualitative research provided a more detailed exploration of the characteristics and sources of negative psychological states of infertile women, which yielded five key themes: characteristics of a negative psychological state, medical aspects, family issues, conflicts with normal life, and social context influences. The prevalence of a negative psychological state is high among infertile Chinese women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment. The results of mixed-methods study reveal that medical factors associated with assisted reproductive treatment, insufficient family emotional support, conflicts between work and treatment, and financial burdens are the main causes of negative psychological states. Future research needs to explore more effective psychological intervention methods to improve the psychological state of infertile women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infertility is a reproductive disorder that is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the failure to achieve clinical pregnancy after regular unprotected intercourse for 12 months or more. Currently, the number of couples experiencing infertility has reached alarming proportions and continues to increase1. According to the latest report published by the WHO, approximately 17.5% of the adult population experiences infertility, accounting for approximately 1 in 6 individuals worldwide2. Therefore, an increasing number of couples are seeking assisted reproductive treatment. Assisted reproductive treatment mainly includes artificial insemination (AI) and assisted reproductive technology (ART)3. Globally, approximately 2.5 million ART cycles are performed annually, and the total number of births has exceeded 8 million4. In China, the development of ART has been particularly rapid, and the number of babies conceived through ART has exceeded 300,000 per year, accounting for 1.69%~ 3% of the total number of births since 20165.

Because infertility and assisted reproductive treatment are both high-pressure situations, the psychological status of infertile women undergoing infertility treatment has been studied. Previous findings have suggested that infertile women are more likely to have a negative psychological state, particularly anxiety, depression and stress6,7,8. The prevalence of a negative psychological state is even greater among those seeking assisted reproductive treatment8,9. Possible reasons are as follows. Firstly, sociocultural and personal attitudes are influenced by the fact that infertility may be considered shameful, and many couples are reluctant to publicly admit to such problems10. There is a tendency for society to think that “infertility is always the woman’s fault”11,12. Secondly, assisted reproductive treatment, which involves numerous nonphysiological procedures, can be extremely stressful13. Hormone therapy and medical monitoring may have different impacts on patients’ psychological states14,15. Moreover, the failure of treatment is another important factor that can lead to psychological disorders. Although assisted reproduction has allowed numerous infertile couples to achieve pregnancy, implantation failure and consecutive pregnancy losses, which are triggering factors for prolonged grief in infertile women, still have high incidence rates16.

The high prevalence of negative psychological states in infertile women may have profound effects on various aspects of their daily lives, such as sexual functioning and family relationships13,17. Evidence also suggests that psychological anxiety and distress before or during assisted reproductive treatment may jeopardize the likelihood of pregnancy. Though results are controversial in this respect18,19,20, there are meta-analyses suggesting that stress levels during ART are negatively associated with clinical pregnancy and live birth rates20,21. The presence of a negative psychological state is also one of the important reasons why patients discontinue ART treatment13,22. Therefore, researchers have begun to focus on psychological interventions to improve the quality of life and pregnancy outcomes of infertile women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment. However, some studies have suggested that psychotherapy could be efficacious in reducing the psychological distress and/or improving the ART outcomes of infertile women, but others have revealed the opposite23,24,25. A recent meta-analysis of randomised control trials (RCTs) revealed that psychological interventions are only associated with slight reductions in patients’ distress and moderate effects on ART outcomes26.

These inconsistent research findings suggest that the effectiveness of psychological interventions may be influenced by individual risk factors, which have not yet been systematically identified or thoroughly investigated27. Most studies on the negative psychological states of infertile women have focused mainly on the relationships between psychological distress and stigma or ART outcomes12,27. Only a few studies have investigated the risk factors11,28. Age, education level, reproductive history, family income and partner depression are common risk factors for a negative psychological state16,29. Moreover, the limited research analysing the causes of negative psychological states has focused mainly on questionnaire surveys, with only preliminary analysis of the causes. This approach fails to uncover the complex pathways underlying negative psychosocial states, potentially obscuring key intervention targets. To develop effective psychological interventions, it is necessary to fully understand the underlying risk factors for negative psychological states in infertile women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment.

The aim of this study was to assess the current psychological situation of infertile women and identify the specific risk factors for negative psychological states to understand the psychological challenges faced by these women during the infertility treatment process and provide a theoretical basis for the development of effective psychological interventions. Here, we enrolled 437 infertile women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment and conducted a mixed-methods study involving questionnaires and interviews. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use a mixed-methods design by using the DASS − 21 to assess the psychological states of infertile women and analyse the risk factors for negative psychological states.

Methods

Study design

This study adopted an explanatory sequential mixed-method design to collect data on the psychological states of infertile women from multiple perspectives. A mixed-methods design is a paradigm that integrates elements of both quantitative and qualitative research, aiming to provide richer data for a better understanding of research phenomena and to enhance the credibility, depth, and breadth of a study30,31. First, we conducted a quantitative survey to evaluate the prevalence of negative psychological symptoms, including anxiety, depression and stress, in a sample of infertile women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment. We subsequently conducted a qualitative analysis (semistructured interviews) among infertile women who reported negative psychological symptoms to clarify their feelings and analyse the causes of their negative psychological state.

Participants

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, Hangzhou Medical College (Ethics No. KY2024014, Hangzhou, China). The ethical standards adhered to by this research are in accordance with the 2013 version of the Helsinki Declaration. Between June 2023 and May 2024, infertile female patients undergoing assisted reproductive treatment at the Department of Reproductive Endocrinology, Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, were recruited for the study. The inclusion criteria for the quantitative research part were: (1) clinical diagnosis of infertility; (2) beginning a cycle of AI or ART; (3) willingness to participate in the study and provide informed consent; and (4) adequate reading comprehension skills to accurately respond to the questionnaire items. The exclusion criteria were: (1) reliance on ART to preserve fertility due to cancer treatment; and (2) limited cognitive and judgemental abilities and the inability to understand and consent to the study. The sample size for the quantitative study was determined on the basis of an empirical rule, where the sample size is typically 10 to 20 times the number of research variables. This study includes 12 variables, considering a 10% expected rate of invalid samples, the minimum required sample size was 143 participants. For the quantitative part of the study, convenience sampling was used. When infertile women established their medical records and confirmed their decision to undergo assisted reproductive treatment at the study center, they were invited to participate in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment in this mixed-methods study. Before starting the investigation, the participants were informed about the purpose of the study and their rights through an information sheet. Data collected from the participants were confidential and stored in accordance with applicable data protection regulations to ensure privacy.

The purposive sampling method was employed to screen eligible participants from the infertile women who had already completed the questionnaire survey for qualitative interviews. The determination of the interviewees in this qualitative study adhered to the principles of maximum variation and information saturation. The principle of maximum variation emphasized the selection of samples with heterogeneous characteristics, aiming to cover diverse dimensions of the research phenomenon. This approach enhanced the comprehensiveness and explanatory power of the research findings. The principle of information saturation entailed continuous data collection and analysis until new data no longer generated novel themes or insights, at which point the sampling process was terminated32. Specifically, initially, the research team engaged in extensive communication with women whose scores on the DASS-21 met the criteria of ≥ 10 for depression, ≥ 8 for anxiety, and/or ≥ 15 for stress (indicating at least mild symptoms in any dimension of depression, anxiety, and/or stress), fully respecting their autonomy in making decisions regarding participation in the interviews. Subsequently, sociodemographic factors and treatment-related factors of the infertile women were taken into account. The qualitative interviewees ultimately included in the study exhibited notable heterogeneity in aspects such as occupation, income, causes of infertility, treatment duration, and previous cycles of ART treatment. Finally, the interviews were halted when no new information emerged and the data reached saturation.

Clinical data collection

The participants’ demographic information and clinical data were collected from their electronic medical records. Demographic information included age, body mass index (BMI), educational attainment, occupation type and family income. Clinical data included infertility-related factors (reproductive history, duration of infertility, and causes of infertility) and treatment characteristics (duration of assisted reproductive therapy, history of assisted reproductive treatment, and current treatment protocol).

Quantitative measurements

The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-Short Form (DASS-21), which was originally developed in 199533,34 and comprises 21 items, was used to assess the following three dimensions of patients’ negative mental states: Depression (7 items), an example of which includes “I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feelings at all”; Anxiety (7 items), an example of which includes “I was aware of dryness of my mouth”; and Stress (7 items), an example of which includes “I found it hard to wind down” (Supplemental file 1). The items are scored on a four-point Likert-type scale (0 = “Did not apply to me at all” to 3 = “Applied to me very much”). The standard scores for each subscale are derived by multiplying the respective subscale scores by a factor of 2, and the score of each subscale ranges from 0 to 42 points. According to the judgement criteria, participants with a standard score ≥ 10 points on the depression subscale were considered at risk for depression, participants with a standard score ≥ 8 points on the anxiety subscale were considered at risk for anxiety, and participants with a standard score ≥ 15 points on the stress subscale were considered at risk for stress, and a higher score indicated greater risk35.

Qualitative interviews

A semistructured interview guide was used to conduct individual face-to-face interviews with a subsample of participants with depression, anxiety and/or stress symptoms. Following the confirmation of the study’s main objectives, we reviewed the relevant literature to understand the existing knowledge and theoretical framework of the research topic. The interview guide was created through discussion among a reproductive specialist, a psychiatrist and nurses and included four themes: (1) the psychological status of infertile women; (2) the impact of family factors on the mental health of women undergoing infertility treatment; (3) the influence of social relationships on the psychological status of women; and (4) the effects of medical factors on the mental health of women. Detailed information is shown in Supplemental file 2.

Pretesting was conducted before the formal interviews, and the questions were flexibly adjusted according to the instructions on the basis of the respondents’ answers36. The interviews were conducted by a master’s student who was trained and supervised by an experienced nurse who is a national third level psychological counselor. Before the formal interview, we conducted repeated training and simulations to ensure quality. The interviews were conducted in a private room during the patients’ medical visits. Each interview lasted approximately 30 to 60 min, depending on the course of the conversation. Prior to the start of the interviews, all the participants were informed that the sessions would be audio-recorded and documented. The recordings were transcribed verbatim after each session.

Data analysis

Quantitative analyses

SPSS 26.0 was used for all quantitative statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics are expressed as the means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables and as frequencies and proportions for dichotomous variables. The potential factors related to differences in depression, anxiety and stress, such as age, educational attainment, family income, occupation type, infertility duration, infertility factors, and treatment history, were analysed via t tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA), or nonparametric tests. Separate multivariate linear regression analyses were performed with negative psychological scores as the dependent variables and statistically significant variables from univariate analysis as the independent variables.

Qualitative analyses

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the qualitative data. The six steps of thematic analysis were conducted according to the references: familiarization with the data; generating codes; searching for themes; reviewing the themes; defining and naming the themes; producing the report37. Three researchers jointly analysed the interview data. The qualitative analysis software NVivo 14.0 was used to organize the data codes. First, the interview transcripts were analysed sentence-by-sentence, and initial codes were identified. Then, the codes were sorted into subthemes on the basis of similarities and differences. The subthemes were ultimately categorized into themes, each theme was defined and explained, resulting in the final interview report. To ensure the accuracy and confirmability of the data, all audio recordings were transcribed verbatim immediately after each interview. The transcripts were then cross-checked by two researchers to ensure accuracy, and any uncertainties were clarified by returning to the interviewees for confirmation. To reduce potential bias, three researchers independently coded and analysed the data. After initial coding, they compared their results and discussed any discrepancies until consensus was reached.

Results

Quantitative data

Participant characteristics

A total of 437 infertile women beginning assisted reproductive treatment were included in the questionnaire study. Among these women, 331 (75.7%) were starting an ART cycle, and 106 (24.3%) were starting an AI cycle. A total of 370 (84.7%) women were undergoing assisted reproductive treatment for the first time. The clinical characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Depression, anxiety, and stress status of the participants

As shown in Table 2, among the 437 women, 47 women (10.8%) reported experiencing depressive symptoms. 106 women (24.3%) had anxiety symptoms, 38 women (8.7%) reported feeling stressed. Among them, 35 women (8%) exhibited symptoms of both depression and anxiety. 21 women (4.8%) experienced both depressive and stress symptoms, whereas 31 women (7.1%) reported symptoms of both anxiety and stress. Finally, 18 women (4.1%) had all three types of negative psychological symptoms simultaneously.

Analysis of negative psychological states in infertile women

To further investigate the risk factors for negative psychological states, we conducted univariate analysis to statistically analyse the negative psychological scores of women with different sociodemographic characteristics. As shown in Table 1, in terms of the depression and anxiety, the main factors affecting the scores were occupation type, family income, duration of infertility treatment and history of assisted reproductive treatment. With respect to occupation type, workers and other manual labourers and unemployed individuals had significantly higher scores for depression and anxiety. The group with high family income had significantly lower scores for depression, anxiety, and stress. For the clinical data, the group with a history of assisted reproductive treatment and the group with a moderate duration (1–3 years) of infertility treatment had significantly higher scores for depression and anxiety. In the dimension of stress, family income significantly affected the women’s stress scores, which was reflected by a lower level of stress in women with high family income. In terms of infertility factors, women in the group with female infertility had significantly greater stress levels than those with combined factors or male infertility, whereas the group with unexplained infertility received the lowest score. Consistent with depression and anxiety, the group with a history of assisted reproductive treatment and the group with 1–3 years of infertility treatment had higher stress scores.

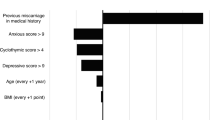

Separate multivariate linear regression analyses

Separate multivariate linear regression analyses were performed with depression, anxiety, and stress scores as the dependent variables and the five statistically significant variables from the univariate analysis as the independent variables. Dummy variables were set for categorical variables. As shown in Table 3, the results of the multivariate linear regression analysis indicated that annual per capita household income was the primary factor influencing depression scores among women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment. The duration of infertility treatment and occupation type were the primary factors affecting anxiety scores, whereas unexplained infertility was the main factor influencing stress scores among women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment.

Qualitative data

Fourteen participants participated in individual interviews, each of whom received a high score in at least one dimension (depression, anxiety and stress). Table 4 presents the characteristics of these 14 women. The content of the interviews was analysed using thematic analysis, leading to the identification of five key themes: characteristics of a negative psychological state, medical aspects, family issues, conflicts with normal life, and social context influences. Each theme includes corresponding subthemes that were assigned numerical codes. Their respective frequencies were calculated. Detailed thematic information and selected quotes are listed in Table 5. The following sections present each theme and its subthemes.

Theme 1: characteristics of a negative psychological state

The subthemes under the theme “Characteristics of a negative psychological state” were diversity, various triggers leading to different outcomes and continuous impact throughout treatment. This theme emphasizes the pervasiveness and complexity of negative emotions across the entire treatment process, highlighting the necessity for ongoing psychological support.

Diversity

Infertile women may experience various negative psychological symptoms, including anxiety, stress, low self-esteem, fear, and pessimism. Different individuals may exhibit similar or distinct negative psychological responses, whereas the same individual may experience multiple negative psychological symptoms.

Various triggers leading to different outcomes

Infertile women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment may develop a negative psychological state. When women experience challenges such as physical discomfort or treatment failure during treatment, they may experience negative emotions, including fear, anxiety, confusion, and avoidance. Treatment failure is the factor that most significantly triggers negative emotions in patients. Initially, women may find it difficult to accept this outcome, but these emotions gradually subside over time. This reflects patients’ self-adaptation to negative psychology states, which serves as a result of self-regulation and a coping mechanism.

Continuous impact throughout treatment

Women may experience negative psychological responses at any stage of assisted reproductive treatment. For example, they may feel apprehensive about upcoming procedures before treatment begins, experience anxiety prior to oocyte retrieval and embryo transfer, and worry about the outcomes after procedures.

Theme 2: medical aspects

The subthemes under the theme “Medical aspects were side effects, unpredictable results, healthcare providers, and the treatment process. This theme emphasizes how medical procedures and provider interactions can directly influence women’s emotional well-being during treatment.

Side effects

The surgical procedures and hormone injections involved in assisted reproductive treatment can induce pain and discomfort. Additionally, women express concerns about the potential impacts of treatment on their overall health. For example, ovarian hyperstimulation may lead to ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), resulting in ascites and other conditions causing discomfort. Women have also expressed concerns that hormone injections may have adverse effects on ovarian function or changes in body image, such as weight gain and increased body hair.

Unpredictable results

These unpredictable results often lead to fluctuations in women’s psychological states. For example, women may experience anxiety and confusion due to treatment changes or interruptions caused by medical factors. Additionally, previous experience of treatment failure may lead to concerns in the next cycle, and the inability to determine the cause of treatment failure further exacerbates these worries.

Healthcare providers

Participants have reported that poor service attitudes among healthcare providers can have a negative impact on their psychological condition, with the main problem being a lack of patience. In addition, the communication skills of medical staff can influence patients’ experiences. For example, doctors may present information in a direct manner that patients find difficult to accept, or patients might set unrealistic expectations for treatment outcomes. When the eventual outcomes do not meet these expectations, patients may struggle to cope with the disappointing reality.

Treatment process

Some women have reported that long waiting times for meetings with healthcare providers, insufficient protection of their personal privacy, and excessive procedural care negatively impact their experiences and emotions. They feel that there is a lack of individual attention to their specific needs during consultations.

Theme 3: family issues

The subthemes under the theme “Family issues” were excessive concern, a lack of action, and insufficient psychological support. This theme reflects how familial dynamics and emotional imbalance within relationships can contribute to psychological distress in infertile women.

Excessive concern

Both partners within a couple often put pressure on themselves to become pregnant as soon as possible, which can create significant stress for the woman, as she may feel unable to meet family expectations. Even when a couple is undergoing IVF treatment, their elders may excessively inquire about the progress and outcomes of the treatment and may even interfere with the couple’s normal daily life.

Lack of action

During the process of assisted reproductive treatment, men are generally reluctant to seek additional information related to fertility. They tend to be less proactive and unwilling to engage in activities such as exercise or smoking cessation to improve treatment outcomes. This significant difference in effort compared with that of women may make infertile women experience a sense of imbalance and unfairness.

Insufficient emotional support

Because male partners and other family members experience much less physical distress than female partners do, they may lack a deep understanding of assisted reproductive treatment and find it difficult to understand the physiological and psychological challenges experienced by their female partners. Moreover, the economic and emotional pressures associated with assisted reproductive treatment may cause anxiety for other family members, leaving them with insufficient resources to support the emotional needs of the woman undergoing treatment.

Theme 4: conflicts with normal life

The subthemes under the theme “Conflicts with normal life” were time conflicts between work and treatment, financial burden, and a decline in quality of life. This theme illustrates how reproductive treatment disrupts women’s work-life balance and daily functioning, thereby reducing life satisfaction.

Time conflicts between work and treatment

Many women mention time conflicts between their work and medical treatment, expressing frustration over the need for frequent hospital visits that require them to take time off. Moreover, due to the demand for treatment, some women have to leave their jobs or transition to less demanding positions with limited career opportunities.

Financial burden

Family financial burden originates from two aspects: the significant costs associated with assisted reproductive treatment and a woman’s inability to concentrate on work during the treatment period, which negatively affects household income.

Decline in quality of life

Many women often find themselves involuntarily thinking about assisted reproductive treatment in their daily lives, which increases their psychological burden. Some participants spend considerable time travelling to the hospital, leading to feelings of exhaustion. Therefore, they may be forced to change their lifestyle habits, leading to a decline in their overall quality of life.

Theme 5: social context influences

The subthemes under the theme “Social context influences” were traditional sociocultural stressors, social difficulties, and the influence of other patients. This theme reveals how societal and peer-related pressures shape women’s self-perception and emotional responses to infertility.

Traditional sociocultural stressors

Participants may be influenced by traditional Chinese beliefs, including that childbirth is highly important for a person’s survival and the continuation of a family. Therefore, women may experience shame due to infertility and the need for assisted reproductive treatment.

Social difficulties

Compared with their peers, infertile women often experience distress due to delayed life progress. This distress is exacerbated in social situations, where infertile women may struggle to engage in conversations centred on children. When these women invest significant effort in trying to conceive but are unsuccessful, they may feel frustrated and even jealous, especially of their friends who easily conceive.

The influence of other patients

Infertile women are significantly influenced by other patients, who often exchange information and express their emotions. Infertile women may feel envious when someone successfully conceives and experience concern about their own treatment outcomes when others are unsuccessful. In addition, when patients’ treatment progress lags behind that of patients with similar conditions, they may also experience anxiety.

Discussion

This study aimed to comprehensively assess the psychological status of infertile women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment and to identify the underlying causes of their negative psychological feelings. Our findings suggest that the prevalence of anxiety, followed by depression and stress, in infertile women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment is remarkably high. This result is consistent with those of previous studies16,38,39,40. This situation prompted us to identify the causes of adverse psychological conditions to guide the development of targeted psychological interventions. In this study, we used a mixed research method that combined the acquiring of quantitative data on depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms, as measured by the DASS-21, and of qualitative interview data to comprehensively assess the psychological status of infertile women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment. In the quantitative part of the study, we conducted a stratified analysis based on the sociodemographic and medical information about the included participants. The results revealed that negative psychological states in infertile women are related to occupation type, household income, infertility factors, duration of infertility treatment, and the number of previous assisted reproductive treatment cycles. However, the multivariate linear regression model indicated that these existing factors can predict only part of the reason as the value of R2 is low. Subsequent qualitative research, conducted by interviewing high-scoring women, provided a more detailed exploration of the characteristics and sources of negative psychological states in infertile women. Negative emotions such as low self-esteem, fear, and pessimism were also identified during the interviews. This analysis yielded five key themes: characteristics of a negative psychological state, medical aspects, family issues, conflicts with normal life, and social context influences. The results of mixed-methods study reveal that medical factors associated with assisted reproductive treatment, insufficient family emotional support, conflicts between work and treatment, and financial burdens are the main causes of negative psychological states.

Impact of medical factors of assisted reproductive treatment

Medical factors associated with assisted reproductive treatment have a particularly significant effect on the mental health of women. First, our results showed that the duration of assisted reproductive treatment and a history of treatment cycles significantly affected all three negative psychological scores. Previous ART studies also reported that the experience of treatment failure and uncertainty about the outcome of treatment were predictors of psychological distress41,42. Treatment failure not only triggers excessive anxiety when the cause is unknown but also causes patients to experience confusion about whether to continue treatment in the future43. Second, patients were concerned about the possible side effects of assisted reproductive treatment. In our study, the patients reported experiencing health problems such as discomfort and mood swings due to hormone injections, oocyte retrieval surgery, and so on. Third, the complexity of the treatment process is another reason for patients’ negative psychology. In the quantitative research, interestingly, compared with hopeful patients with short-term treatment and good adaptation after long-term treatment, women with a moderate duration (1–3 years) of infertility treatment had higher scores for depression, anxiety and stress. This result is consistent with the literature44. Surprisingly, quantitative analysis revealed no significant difference in negative psychological scores between women receiving AI treatment and ART treatment. Perhaps because, regardless of the type of treatment received, owing to the uncertainty of outcomes, patients view the results of each stage as a test and experience immense psychological pressure45. Patients’ negative psychological feelings are more pronounced if they encounter medical staff with inappropriate coping attitudes during this complex treatment process.

Insufficient family emotional support

Family emotional support is also an important aspect that affects the mental health of infertile women. Qualitative interviews revealed that women in treatment stage were particularly influenced by their social and family environments. According to the social support theory46, familial support encompasses not only relatives’ involvement but also emphasizes the pivotal role of spousal support within the social support framework. Insufficient family emotional support, especially from the male partner, is an important cause of adverse psychological conditions in infertile women. In most East Asian families that prioritize lineage continuity, women bear the primary responsibility of reproduction. Infertility is often considered as the woman’s fault47. Therefore, although pregnancy is a matter for both partners, men are less involved and endure less hardship than women during assisted reproductive treatment. Some male partners are reluctant to take positive measures such as smoking cessation and exercise to improve the success rate of treatment. They often lack concern and empathy for their female partners and may even blame them when discussing the cause of infertility, even if the cause of infertility may be male factors. These behaviours and attitudes may worsen the psychological burden on infertile women48,49. Moreover, the behavior of other relatives, such as urging, blaming, and even excessive concern, can affect women’s psychological state. This has also been reported in other Asian countries such as Japan and Vietnam48,50. In contrast, the provision of social and emotional support to infertile women by their male partners and close relatives can alleviate their negative emotions during treatment51.

Conflicts between work and assisted reproductive treatment

In terms of occupation type, our quantitative research revealed significant differences in anxiety and depression scores among women in different job categories, with workers and other manual labourers obtaining the highest scores. In the qualitative interviews, the participants also expressed frequent concerns about time conflicts between work and assisted reproductive treatment. Frequent medical visits inevitably affect women’s work schedules, thereby increasing negative emotions. In addition to the impact of time management, the conflict between work and treatment also manifests in the negative emotions that affect work quality and the challenge of personal promotion. Courbiere et al. reported that almost half of women who underwent assisted reproduction reported a negative impact on the quality of work or the need to lie about missing work14. Therefore, even without considering economic factors, the conflict between work and assisted reproductive treatment could still strongly affect the psychological states of infertile women.

Trouble with financial issues among women undergoing infertility treatment

Both our quantitative and qualitative studies showed that income level affects adverse psychological conditions in participants. A previous study in Romania9 also indicated that family income was the most important factor influencing the stress levels of infertile women. On the one hand, this is due to the high cost of assisted reproductive treatment and the fact that patients are unsure whether the high-cost treatment will result in pregnancy or how much they need to spend continually. On the other hand, assisted reproductive treatment has an impact on women’s work, leading to a decrease in family income14. More expenses and less family income further exacerbate the family’s economic crisis.

Future directions

Given the widespread and interconnected psychological burden of infertile women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment, we suggest that future research should aim to improve the efficiency of available psychological interventions. The theory of stress and coping states that the effectiveness of an intervention depends on the fit between the stressors experienced and the strategies used to address them52. Interventions need to start by improving the external environment, such as enhancing medical care conditions and strengthening social support systems, as well as providing psychological treatment for infertile women. In terms of healthcare, in addition to continuously improving the safety and success rates of assisted reproductive treatment, optimizing medical treatment procedures, fully informing patients, and providing training for medical staff are very important. These training programs should focus on enhancing professional operational skills, improving communication abilities, and strengthening the concept of patient-centered care throughout the entire assisted reproductive treatment process. In terms of the social environment, on the basis of the theory of social support46, the most important goal is to obtain emotional support from relatives, especially physical and mental support from male partners. Additionally, targeted and individualized psychological treatment is necessary for women in need. The most suitable treatment approach and modality for patients should be chosen on the basis of their preferences26.

Strengths and limitations

In this study, we used the DASS-21 to perform quantitative measurements, this scale has good reliability and validity and has been widely applied in research across various fields53. To our knowledge, this is the first study in China to apply the DASS-21 in psychological research on infertile women. The strength of our study is the use of a mixed-methods approach. With respect to the cross-sectional questionnaire, we conducted a stratified analysis of the basic information of the included participants and interviewed high-scoring women. Qualitative interviews further supplemented the closed-ended questionnaire, and its content partially demonstrates the mechanisms through which these factors exert their influence, allowing for an in-depth exploration of sensitive emotions and factors not captured by the questionnaire. This information provides a valuable theoretical basis for the implementation of psychological interventions for infertile women. Secondly, compared with previous studies in which participants were required to complete lengthy questionnaires with numerous items54,55, in this study, the DASS-21, which is more concise and easier to understand, was used, thus reducing the burden on participants and improving the reliability of the results. Moreover, in the quantitative research part of this study, we collected more than 400 questionnaires and comprehensively gathered the sociodemographic data and treatment data of infertile women, thus establishing a relatively adequate data foundation. Based on such diverse and substantial data, this study can reliably reflect the actual situation of infertile women, providing solid support for the research conclusions. However, this study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample in this study was from a single centre, which may affect the broad applicability of the results. Secondly, the study lacks longitudinal data, making it impossible to track the changes in the psychological states of infertile women over time. In addition, the quantitative research part of this study only focused on depressive, anxious, and stress symptoms, without covering other possible psychiatric diagnoses or symptoms. Future research can further improve and expand in response to these deficiencies.

Conclusion

The results of this mixed-methods study revealed that the prevalence of negative emotions, including depression, anxiety and stress, is high among infertile Chinese women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment. Medical factors associated with assisted reproduction, insufficient family emotional support, conflicts between work and treatment, and financial burdens are the main factors related to negative psychological states. These findings underscore the importance of integrating psychological care into assisted reproductive treatment, particularly within culturally specific contexts such as China, and psychological interventions that take these factors into account may become more effective. Future research could explore tailored, multidisciplinary interventions that involve medical staff, mental health professionals, and family members. In addition, longitudinal studies are warranted to assess the long-term psychological trajectories of women undergoing assisted reproduction and to evaluate the sustained effectiveness of targeted interventions.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the privacy of the participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AI:

-

Artificial insemination

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- ART:

-

Assisted reproductive technology

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DASS-21:

-

The depression, anxiety, and stress scale-short form

- IVF-ET:

-

In vitro fertilization-embryo transfer

- OHSS:

-

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

- RCTs:

-

Randomised control trials

- SDs:

-

Standard deviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Beaujouan, E. Latest-Late fertility?? Decline and resurgence of late parenthood across the Low-Fertility countries. Popul. Devel Rev. 46, 219–247 (2020).

Infertility Prevalence Estimates, 1990–2021. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/978920068315 (Accessed 29 May 2023).

Zou, K., Ding, G. & Huang, H. Advances in research into gamete and embryo-fetal origins of adult diseases. Sci. China Life Sci. 62, 360–368 (2019).

Zhang, S. et al. Long-term health risk of offspring born from assisted reproductive technologies. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 41, 527–550 (2024).

Bai, F. et al. Assisted reproductive technology service availability, efficacy and safety in Mainland China: 2016. Hum. Reprod. (Oxford, England) 35, 446–452 (2020).

Chaves, C., Canavarro, M. C. & Moura-Ramos, M. The role of dyadic coping on the marital and emotional adjustment of couples with infertility. Fam Process. 58, 509–523 (2019).

Purewal, S., Chapman, S. C. E. & van den Akker, O. B. A. Depression and state anxiety scores during assisted reproductive treatment are associated with outcome: a meta-analysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 36, 646–657 (2018).

Kato, T., Sampei, M., Saito, K., Morisaki, N. & Urayama, K. Y. Depressive symptoms, anxiety, and quality of life of Japanese women at initiation of ART treatment. Sci. Rep. 11, 7538 (2021).

Margan, R. et al. Impact of stress and financials on Romanian infertile women accessing assisted reproductive treatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 3256 (2022).

Pacheco Palha, A. & Lourenço, M. F. Psychological and cross-cultural aspects of infertility and human sexuality. Adv. Psychosom. Med. 31, 164–183 (2011).

Zhu, C. et al. Incidence and risk factors of infertility among couples who desire a first and second child in shanghai, china: a facility-based prospective cohort study. Reproductive Health. 19, 155 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. The social stigma of infertile women in Zhejiang province, china: a questionnaire-based study. BMC Women’s Health. 21, 97 (2021).

Gameiro, S., Boivin, J., Peronace, L. & Verhaak, C. M. Why do patients discontinue fertility treatment? A systematic review of reasons and predictors of discontinuation in fertility treatment. Hum. Reprod. Update. 18, 652–669 (2012).

Courbiere, B. et al. Psychosocial and professional burden of medically assisted reproduction (MAR): results from a French survey. PLOS ONE. 15, e0238945 (2020).

Timmons, D., Montrief, T., Koyfman, A. & Long, B. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: A review for emergency clinicians. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 37, 1577–1584 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors for anxiety and depression in infertile couples of ART treatment: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 22, 616 (2022).

Facchin, F. et al. Infertility-related distress and female sexual function during assisted reproduction. Hum. Reprod. 34, 1065–1073 (2019).

Boivin, J., Griffiths, E. & Venetis, C. A. Emotional distress in infertile women and failure of assisted reproductive technologies: meta-analysis of prospective psychosocial studies. BMJ 342 (2011).

Nicoloro-SantaBarbara, J. M. et al. Psychological and emotional concomitants of infertility diagnosis in women with diminished ovarian reserve or anatomical cause of infertility. Fertil. Steril. 108, 161–167 (2017).

Peaston, G., Subramanian, V., Brunckhorst, O., Sarris, I. & Ahmed, K. The impact of emotional health on assisted reproductive technology outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Fertil. (Camb). 25, 410–421 (2022).

Matthiesen, S. M. S., Frederiksen, Y., Ingerslev, H. J. & Zachariae, R. Stress, distress and outcome of assisted reproductive technology (ART): a meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. (Oxford England). 26, 2763–2776 (2011).

Rich, C. W. & Domar, A. D. Addressing the emotional barriers to access to reproductive care. Fertil. Steril. 105, 1124–1127 (2016).

Gaitzsch, H., Benard, J., Hugon-Rodin, J., Benzakour, L. & Streuli, I. The effect of mind-body interventions on psychological and pregnancy outcomes in infertile women: a systematic review. Archives Women’s Mental Health. 23, 479–491 (2020).

Zhou, R., Cao, Y. M., Liu, D. & Xiao, J. S. Pregnancy or psychological outcomes of psychotherapy interventions for infertility: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 12 (2021).

Katyal, N., Poulsen, C. M., Knudsen, U. B. & Frederiksen, Y. The association between psychosocial interventions and fertility treatment outcome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 259, 125–132 (2021).

Dube, L., Bright, K., Hayden, K. A. & Gordon, J. L. Efficacy of psychological interventions for mental health and pregnancy rates among individuals with infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 29, 71–94 (2023).

Yokota, R. et al. Association between stigma and anxiety, depression, and psychological distress among Japanese women undergoing infertility treatment. Healthc. (Basel Switzerland). 10, 1300 (2022).

Liang, S. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of infertility among 20–49 year old women in Henan province, China. Reproductive Health. 18, 254 (2021).

Wang, L., Tang, Y. & Wang, Y. Predictors and incidence of depression and anxiety in women undergoing infertility treatment: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 18 (2023).

Creswell, J. W. A Concise Introduction To Mixed Methods Research (SAGE, 2021).

Tashakkori, A., Johnson, R. B. & Teddlie, C. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences (SAGE, 2020).

Huang, Y. C., Lei, R. L., Lei, R. W. & Ibrahim, F. An exploratory study of dignity in dementia care. Nurs. Ethics. 27, 433–445 (2020).

Lovibond, S., Lovibond, P., Lovibond, S. & Lovibond, P. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales 2 (1995).

Lovibond, P. F. & Lovibond, S. H. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 33, 335–343 (1995).

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales - DASS. https://www2.psy.unsw.edu.au/DASS/ (Accessed 7 September 2024).

Seidman, I. E. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences (Teachers College, 1991).

Kiger, M. E. & Varpio, L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE guide 131. Med. Teach. 42, 846–854 (2020).

Braverman, A. M., Davoudian, T., Levin, I. K., Bocage, A. & Wodoslawsky, S. Depression, anxiety, quality of life, and infertility: a global lens on the last decade of research. Fertil. Steril. 121, 379–383 (2024).

Shi, L-P. et al. Infertility-related stress is associated with quality of life through negative emotions among infertile outpatients. Sci. Rep. 14, 19690 (2024).

Shayesteh-Parto, F., Hasanpoor-Azghady, S. B., Arefi, S. & Amiri-Farahani, L. Infertility-related stress and its relationship with emotional divorce among Iranian infertile people. BMC Psychiatry. 23, 666 (2023).

Lok, I. H. et al. Psychiatric morbidity amongst infertile Chinese women undergoing treatment with assisted reproductive technology and the impact of treatment failure. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 53, 195–199 (2002).

Verhaak, C. M. et al. Women’s emotional adjustment to IVF: a systematic review of 25 years of research. Hum. Reprod. Update. 13, 27–36 (2007).

Ikemoto, Y. et al. Analysis of severe psychological stressors in women during fertility treatment: Japan-Female employment and mental health in assisted reproductive technology (J-FEMA) study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 304, 253–261 (2021).

Kee, B. S., Jung, B. J. & Lee, S. H. A study on psychological strain in IVF patients. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 17, 445–448 (2000).

de Castro, M. H. M., Mendonça, C. R., Noll, M., de Abreu Tacon, F. S. & do Amaral, W. N. Psychosocial aspects of gestational grief in women undergoing infertility treatment: A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 13143 (2021).

Casale, M. & Carlqvist, A. Is social support related to better mental health, treatment continuation and success rates among individuals undergoing in-vitro fertilization? Systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. PLoS One. 16, e0252492 (2021).

Ying, L. Y., Wu, L. H. & Loke, A. Y. Gender differences in experiences with and adjustments to infertility: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 52, 1640–1652 (2015).

Matsubayashi, H. et al. Increased depression and anxiety in infertile Japanese women resulting from lack of husband’s support and feelings of stress. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 26, 398–404 (2004).

Sambasivam, I. & Jennifer, H. G. Understanding the experiences of helplessness, fatigue and coping strategies among women seeking treatment for infertility - A qualitative study. J. Educ. Health Promot. 12, 309 (2023).

Truong, L. Q. et al. Infertility-related stress, social support, and coping of women experiencing infertility in Vietnam. Health Psychol. Rep. 10, 129–138 (2022).

Anaman-Torgbor, J. A. et al. Experiences of women undergoing assisted reproductive technology in ghana: A qualitative analysis of their experiences. PLoS One. 16, e0255957 (2021).

Folkman, S. & Lazarus, R. S. If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 48, 150–170 (1985).

Yohannes, A. M., Dryden, S. & Hanania, N. A. Validity and responsiveness of the depression anxiety stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) in COPD. Chest 155, 1166–1177 (2019).

Kamboj, N. et al. Women infertility and common mental disorders: A cross-sectional study from North India. PloS One. 18, e0280054 (2023).

Kulaksiz, D. et al. The effect of male and female factor infertility on women’s anxiety, depression, self-esteem, quality of life and sexual function parameters: a prospective, cross-sectional study from Turkey. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 306, 1349–1355 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Min-Juan Wu for her comments on the interview guide and data analyses. We also wish to thank all the women who voluntarily participated in this study.

Funding

This study was funded by the Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project of Zhejiang Province (Ref: 23NDYD23YB), awarded to Dr. Yu Zhang.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JYH contributed to the study design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript drafting and critical discussion. YDW contributed to the study design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data and critical discussion. ZX contributed to data collection and data analysis. MTY was involved in the implementation of the study design, analysis and interpretation of data. YFL assisted in the collection of the data. YTP assisted in the data analysis. XHF contributed to the study design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical discussion. YZ supervised the entire project and was critically involved in the study design, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript drafting and revising. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the study.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, Hangzhou Medical College (No. KY2024014, Hangzhou, China). The ethical standards adhered to by this research are in accordance with the 2013 version of the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment in this mixed methods study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, JY., Wu, YD., Xiao, Z. et al. A mixed-methods study on negative psychological states of infertile women undergoing assisted reproductive treatment. Sci Rep 15, 20916 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06397-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06397-9