Abstract

Female patients with thyroid cancer have a greater desire for not only curing the disease but also leaving an inconspicuous scar. Systematic nursing has a comprehensive effect on reducing scar formation. However, comprehensive nursing guidance for postoperative scar management are not usually available for patients with thyroid cancer. This study aimed to compare the comprehensive effect of systematic nursing compared to traditional nursing measures on postoperative scar management in patients with thyroid cancer. One hundred patients who underwent radical thyroidectomy between January 2019 and June 2019 were selected and randomly assigned to two groups. Patients in the experimental group (n = 50) received nursing care under systematic nursing guidance, while those in the control group (n = 50) received traditional nursing care. In the 3rd, 6th, and 12th months after surgery, all patients returned to the general surgery department for scar evaluation. Scarring was evaluated using the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS). Patients’ self-evaluated satisfaction scores for scar appearance and nursing guidance were also collected. Compared with the control group, scars in the experimental group were less inconspicuous. At the 6th and 12th months after surgery, the total VSS score in the experimental group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P < 0.001). By the 12th month after surgery, patients in the experimental group were more satisfied with the final scar appearance (experimental group: 4.69 ± 0.48; control group: 4.06 ± 0.57; P < 0.01) and nursing care (experimental group: 4.88 ± 0.34; control group: 4.50 ± 0.52; P < 0.05). Systematic nursing guidance had positive effects on reducing scar formation and enhancing patient satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postoperative scars, a natural outcome of wound healing, usually result in a disfigured appearance, particularly in female patients1. The battle against postoperative scarring has been ongoing for several years. Various approaches, such as modified suturing skills, silicone gel application, and pressure therapy exert positive effects on reducing scar formation to some degree2. Physiological scars usually take at least 3 months to mature3. Pathological scars such as hypertrophic scars and keloids may take years to subside or continue to grow over time3. In such cases, scar management usually requires a long-term intervention.

In general surgery, > 50% of patients with thyroid cancer are female, who desire a cure for the disease as well as a better postoperative scar appearance1. Improving postoperative scarring can further enhance patient satisfaction during the follow-up period, making nursing an important part of care4. However, comprehensive nursing guidance for postoperative scar management are not usually available for patients with thyroid cancer. As there are many approaches to scar management, patients can easily become confused. This study provided systematic nursing guidance for postoperative patients with thyroid. Its comprehensive effect on scar management was compared to traditional nursing measures.

Methods

Patients and grouping

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (1-23ZM0041). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to the retrospective nature of the study if informed consent is waived.

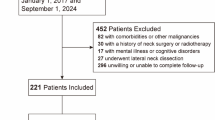

Between January 2019 and June 2019, 100 patients with thyroid cancer (all female) were selected from the Department of General Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital. They were divided into two groups based on a table of random numbers: 50 patients received systematic nursing guidance (experimental group), and the other 50 received traditional nursing guidance.

Computer-generated randomization procedure was used to allocate patients into two groups, in which one got conventional postoperative care and the other got systemic nursing interventions targeted at minimizing scar development. It helped to ensure the robustness and the validity of our findings.

None of the female patients had systemic or chronic diseases; all underwent radical thyroidectomy and were diagnosed with papillary thyroid carcinoma by pathological examination. The same doctor closed the incisions using intradermal sutures and a 3 − 0 absorbable suture (VCP772D; Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Bridgewater, NJ, USA). In all patients, the incisions healed well without infection.

Exclusion Criteria:

-

1.

Patients were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria:

-

2.

Presence of systemic or chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, autoimmune disorders) that could affect wound healing.

-

3.

History of keloid or hypertrophic scar formation.

-

4.

Previous thyroid surgery or other neck surgeries.

-

5.

Incision infection or wound complications during the postoperative period.

-

6.

Incomplete clinical records or follow-up data.

-

7.

Male patients (as the cohort consisted exclusively of females for consistency).

Nursing approaches

Patients in the experimental group received systematic nursing guidance. This approach implemented a systematic care plan that is detailed enough to give explicit attention to three major phases of postoperative care (early, within one month; intermediate, between the second and sixth months; and late, between the seventh and twelfth months), and each includes specific interventions related to changes in physiology and the process of scar maturation taking place at that time. In contrast to routine nursing, which concentrates on immediate postoperative care, the system goes beyond one year after surgery, treating scar care needs in the long term.

To optimize scar outcomes, the following systematic nursing interventions were applied:

Tension-reducing techniques: Tapes and silicone gel sheets were applied regularly from the early recovery stage to reduce mechanical stress on the incision and prevent hypertrophic scarring.

Sun protection education: Patients received guidance on protecting the scar area from UV-induced pigmentation. This included the daily use of sunscreen and physical coverings during outdoor activities.

Scar care goals: These interventions aimed to make scars more pliable and lighter in color—key characteristics evaluated using the Vancouver Scar Scale during follow-up visits.

Active follow-up system: A structured follow-up and reminder system was established by the nursing team. Monthly reminders were sent to patients to reinforce adherence to the scar management protocol.

Individualized feedback: At each follow-up (third, sixth, and twelfth month), personalized feedback was provided based on scar assessment results. Care plans were adjusted as needed to improve outcomes.

Objective outcome monitoring: This structured approach facilitated ongoing, objective evaluation of scar conditions and patient satisfaction over time.

In contrast, the control group received traditional nursing measures, which focused on postoperative nursing after radical thyroidectomy, with no approaches to avoid scar formation. These traditional measures were introduced to patients before surgery and before leaving the hospital. Patients in the experimental group also received monthly reminders from nurses for adherence to systematic nursing guidance. All patients from both groups visited the general surgery outpatient for pictures and assessment of their scar condition in the 3rd, 6th, and 12th months after surgery.

Scar satisfaction evaluation

Scar satisfaction was assessed at the 3rd, 6th, and 12th months after surgery. A five-level satisfaction scale was used in this evaluation process: 1 = deeply unsatisfied, 2 = unsatisfied, 3 = moderate, 4 = satisfying, and 5 = very satisfying. Scar satisfaction was evaluated by a panel consisting of three senior physicians (Professors) specialized in general surgery with clinical experience in postoperative care. This multidisciplinary team approach was intended to enhance the reliability and consistency of the scar assessments.

Vancouver scar scale (VSS)

After operations, we took a detailed look at how our patients’ scars were healing by using the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS), a respected tool that measures scars by looking at their blood supply, height, flexibility, and color. The VSS helps us put a number to the scar’s condition, with 0 meaning the skin is just like new, and 14 pointing to very troubling scars. We kept an eye on the scars over time, which let our experienced team rate their healing process fairly and systematically. This was especially important for the young women we often see, because how a scar looks can really affect them emotionally.

Scar condition evaluation

At the 3rd, 6th, and 12th months of follow-up, the Vancouver Scar Scale1 (VSS) was used by three doctors to evaluate the scar condition of each patient.

Patients’ satisfaction with nursing

Patients evaluated nursing care in the 12th month of follow-up using a five-level satisfaction scale (as explained previously).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). An independent sample t-test was used for group comparisons using SPSS v.24.0. software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All calculated P-values were two-sided, with values < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

No significant differences were found between the two groups regarding age (experimental group: 42.00 ± 7.49 years; control group: 41.13 ± 6.16 years, P > 0.05), body mass index (experimental group: 23.12 ± 2.39 kg/m2; control group: 23.25 ± 2.52 kg/m2, P > 0.05), and incision length (experimental group: 8.25 ± 1.34 cm; control group: 7.81 ± 1.42 cm, P > 0.05). (Table 1)

Scar appearance

Figure 1 shows the scar appearance during the 3rd, 6th, and 12th months of follow-up. Scars in the control group exhibited higher hypertrophic levels in the 6th month, decreasing by the 12th month. Moreover, the scars in the control group were much more obvious than those in the experimental group.

Illustration of scar appearance of typical patients in the experimental and control group. In the 3rd month, scar condition was similar between the experimental and control groups. In the 6th month, the control group showed higher hypertrophic levels, which were then reduced in the 12th month. In the experimental group, scar appearance was similar at each follow-up time. Compared to the control group, the scar from the experimental group is inapparent.

Scar satisfaction from patients, doctors, and nurses

By the 12th month, patients in the experimental group showed higher satisfaction with their scars (P < 0.01), and doctors also reported higher satisfaction with scars among patients in the experimental group (P < 0.05). (Fig. 2; Table 2)

Scar satisfaction evaluation. Experimental group patients have higher satisfaction (P < 0.01) towards scars 12 months after surgery. Doctors showed the same result (P < 0.05). In other follow-up times, no significant difference between the control and experimental groups was found. Even in the 12th month, nurses showed higher satisfaction towards experimental group scars but showed no significant difference.

Scar condition evaluation by VSS

During the 3rd, 6th, and 12th months of follow-up, each aspect of VSS was recorded by specialists. In the 3rd month, patients in the control group showed greater thickness (P < 0.01). However, in the 6th month after surgery, patients in the experimental group showed remarkably lower pigmentation (P < 0.001), vascularization (P < 0.01), thickness (P < 0.01), and pliability (P < 0.05) compared to the control group. By the 12th month, patients in the control group showed higher pigmentation (P < 0.01), vascularization (P < 0.01), and itching (P < 0.01). Significantly higher total scores were found in the control group in the 6th and 12th months after surgery (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3; Table 3).

Scar condition evaluation by VSS. In the 3rd month after surgery, most aspects of VSS showed no significant difference between the two groups except thickness (P < 0.01). In the 6th month, most aspects of VSS showed significant differences except pain and itch. In the 12th month, higher scores for pigmentation (P < 0.01), vascularization (P < 0.01), and itch (P < 0.01) were shown in the control group, who also showed higher total scores in the 6th and 12th months (P < 0.001).

Patients’ satisfaction with nursing care

At the end of this study, patients’ satisfaction with nursing care was assessed. Compared to the control group (4.50 ± 0.52), patients from the experimental group (4.88 ± 0.34) reported significantly higher satisfaction with nursing care (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Surgery is the most effective treatment for thyroid cancer, which is prevalent in China2,3. However, surgery always leaves a long, linear, disfiguring scar. Patients with thyroid cancer have relatively good prognoses after surgical resection. Many studies have focused on new approaches to combat scar formation with the reduction in patient concerns about thyroid tumors in recent years5. Most of these studies used either single or combination therapies6. Although these approaches have achieved certain effects within a certain period, the compliance rate of these patients may not be high, especially regarding invasive treatments or nursing measures. Patient education on scarring should be regular and detailed. However, comprehensive nursing guidance for postoperative scar management are not usually available for patients with thyroid cancer. To help patients understand every key step in antiscar nursing better, our nursing team developed the first systematic and comprehensive nursing guide and evaluated its effectiveness.

Incisions for thyroid cancer are mostly made along the skin lines of the neck. Hence, post-operative neck scarring is generally considered acceptable. Incision healing is divided into inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling processes. The remodeling stage is the most important stage that determines the quality of scar formation, which starts three weeks after incision formation and lasts 6 months4. Kathy et al.7 found that patients were concerned about scarring within a year of thyroid cancer surgery. Therefore, long-term observation and management are required to achieve satisfactory post-operative scars. Postoperative incision nursing care should be continued for a year8.

In our study, the enrolled female patients were followed up for 12 months, and the scarring quality of the patients was evaluated in detail and quantified using the VSS. Systematic nursing guidance were established according to the time after surgery (1st month; 2nd − 6th months; 7th − 12th months). All measures in the systematic nursing guides were noninvasive, which enhanced patient compliance. Since the follow-up lasted for a year, our nurses reminded the patients of the key nursing points monthly to increase their compliance, which was part of the systematic nursing guide. As part of the systematic nursing guidance, monthly reminders were provided to patients to reinforce key aspects of postoperative care. The guidance focused on three main components: Life customs: Patients were advised to avoid activities that might cause excessive tension or friction on the incision site, such as vigorous neck movements or sleeping without proper neck support. Maintaining good rest and avoiding stress were also encouraged, as psychological well-being can influence wound healing. Eating habits: A balanced diet rich in protein, vitamins (especially A and C), and trace elements like zinc was emphasized to promote skin regeneration and reduce the risk of abnormal scarring. Spicy and allergenic foods were discouraged, as they may contribute to local inflammation or delayed healing. Tension-reducing devices: The use of silicone gel sheets and medical tape was encouraged early in recovery to minimize mechanical stress on the incision and prevent hypertrophic scarring. These combined measures aimed to improve compliance, support wound healing, and reduce the incidence of hypertrophic scars or keloids9,10,11,12.

In previous studies, tension control and silicone gel were the most common methods for preventing scar formation due to their convenience and simplicity13,14,15,16. Patients in the experimental group reported no adverse impact on their lives or quality of life from using tension-reducing tape and silicone gel. However, they were willing to follow our guidance because they felt well taken care of by the monthly reminders from the nurses. By the 12th month after surgery, the patients in the experimental group were more satisfied with their scarring appearance and nursing care.

Previous studies have indicated many factors that could contribute to scar formation and appearance, including inflammation17,18, tension19, suture skills20, allergic diseases21, and individual lifestyle habits22. Several recent studies have focused on new approaches to combat scar formation, most of which use single or combination therapies. The VSS is currently the most frequently used scar assessment scale13,14 and is linked with quality of life1. Six aspects were used to evaluate scar conditions: pigmentation, vascularization, thickness, pliability, pain, and itching. Pigmentation is related to ultraviolet rays; therefore, sunscreen is the most effective way to lower the pigmentation score, as shown in our 6th and 12th postoperative month results. Vascularization is key in assessing scar formation and development23,24. Compared with the control group, the vascularization scores at the 6th and 12th post-operative months were much lower in the experimental group; however, no significant difference was found in the 3rd postoperative month. This indicates that improvement in scar vascularization by comprehensive nursing takes at least six months. Thickness and pliability represent scar maturation25. The scores for thickness and pliability in the experimental group were lower than those in the control group, indicating that comprehensive nursing improved scar maturation in the early stages of post-operative scar formation. Symptoms such as pain and itching usually affect patients’ quality of life after surgery26. Patients in the experimental group had no obvious complaints of pain or itching in the 6th month, indicating that a comprehensive nursing strategy can improve patient recovery and quality of life.

According to our results, systematic nursing guides have a promising effect on reducing scar formation and increasing patient satisfaction and are comprehensive, understandable, and practical. However, spontaneous discontinuation of systematic nursing guides may lead to the failure of anti-scar therapy. To solve this problem and increase patient compliance, we reminded patients monthly of the anti-scar key points. Although this might have increased the nurses’ workload, satisfactory results were achieved.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. First, the sample size was limited, which may impact the generalizability of the findings to a larger and more diverse population. Additionally, the study does not provide information about the long-term effects or whether the benefits persist over a more extended period. Despite using monthly reminders to enhance patient compliance, there were challenges in ensuring that all patients followed the systematic nursing guidance consistently. Although this study shows promise, its limitations need to be acknowledged when interpreting the findings.

Conclusion

Post-operative scar management requires long-term nursing care. Systematic nursing guidance can improve scar appearance and increase patient satisfaction.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Finlay, V. et al. Modified Vancouver Scar scale score is linked with quality of life after burn. Burns 43 (4), 741–746 (2017).

Carling, T. & Udelsman, R. Thyroid Cancer. Annu. Rev. Med. 65, 125–137 (2014).

Campagnoli, M. et al. Patient’s Scar satisfaction after conventional thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid Cancer. J. Pers. Med. 13 (7), 1066 (2023).

Kant, S., van den Kerckhove, E., Colla, C., vander Hulst, R. & Piatkowski de Grzymala, A. Duration of Scar maturation: retrospective analyses of 361 hypertrophic Scars over 5 years. Adv. Skin. Wound Care. 32 (1), 26–34 (2019).

Kurumety, S. K. et al. Post-thyroidectomy neck appearance and impact on quality of life in thyroid cancer survivors. Surgery 165 (6), 1217–1221 (2019).

Gentile, R. D. Treating scars to the neck. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. North. Am. 25 (1), 99–104 (2017).

Son, D. & Harijan, A. Overview of surgical Scar prevention and management. J. Korean Med. Sci. 29 (6), 751–757 (2014).

Bach, K. et al. Time heals most Wounds - Perceptions of thyroidectomy scars in patients with thyroid Cancer. J. Surg. Res. 270, 437–443 (2022).

Monstrey, S. et al. Updated Scar management practical guidelines: non-invasive and invasive measures. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 67 (8), 1017–1025 (2014).

Edwards, J. Scars: an overview of current management and nursing care. Dermatological Nurs. 15 (2), 18–25 (2016).

Due, E. et al. Effect of UV irradiation on cutaneous cicatrices: a randomized, controlled trial with clinical, skin reflectance, histological, immunohistochemical and biochemical evaluations. Acta Derm Venereol. 87 (1), 27–32 (2007).

Li-Tsang, C. W., Lau, J. C., Choi, J., Chan, C. C. & Jianan, L. A prospective randomized clinical trial to investigate the effect of silicone gel sheeting (Cica-Care) on post-traumatic hypertrophic Scar among the Chinese population. Burns 32 (6), 678–683 (2006).

Byrne, M. & Aly, A. The surgical suture. Aesthet. Surg. 39 (Suppl 2), S67–S72 (2019).

Grabowski, G., Pacana, M. J. & Chen, E. Keloid and hypertrophic Scar formation, prevention, and management: standard review of abnormal Scarring in orthopaedic surgery. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 28 (10), e408–e414 (2020).

Rabello, F. B., Souza, C. D. & Farina Júnior, J. A. Update on hypertrophic Scar treatment. Clinics 69 (8), 565–573 (2014).

Zoumalan, C. I. Topical agents for Scar management: are they effective? J. Drugs Dermatol. 17 (4), 421–425 (2018).

Eming, S. A., Wynn, T. A. & Martin, P. Inflammation and metabolism in tissue repair and regeneration. Science 356 (6342), 1026–1030 (2017).

Ogawa, R. Keloid and hypertrophic scars are the result of chronic inflammation in the reticular dermis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 (3), 606 (2017).

Song, H. et al. Tension enhances cell proliferation and collagen synthesis by upregulating expressions of integrin alphavbeta3 in human keloid-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Life Sci. 219, 272–282 (2019).

Başbuğ, A., Doğan, O., Ellibeş Kaya, A., Pulatoğlu, Ç. & Çağlar, M. Does suture material affect uterine Scar healing after Cesarean section? Results from a randomized controlled trial. J. Invest. Surg. 32 (8), 763–769 (2019).

Komi, D. E. A., Khomtchouk, K. & Santa Maria, P. L. A review of the contribution of mast cells in wound healing: involved molecular and cellular mechanisms. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 58 (3), 298–312 (2020).

Wallace, H. J., Fear, M. W., Crowe, M. M., Martin, L. J. & Wood, F. M. Identification of factors predicting Scar outcome after burn in adults: a prospective case-control study. Burns 43 (6), 1271–1283 (2017).

Korntner, S. et al. Limiting angiogenesis to modulate Scar formation. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 146, 170–189 (2019).

DiPietro, L. A. Angiogenesis and wound repair: when enough is enough. J. Leukoc. Biol. 100 (5), 979–984 (2016).

Li, P. et al. The recovery of post-burn hypertrophic Scar in a monitored pressure therapy intervention programme and the timing of intervention. Burns 44 (6), 1451–1467 (2018).

Berman, B., Maderal, A. & Raphael, B. Keloids and hypertrophic scars: pathophysiology, classification, and treatment. Dermatol. Surg. 43 (Suppl 1), S3–S18 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all laboratory members for their critical discussion of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-B-130).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZY collected the data and wrote the draft, and created the figures and table. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (1-23ZM0041). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to the retrospective nature of the study the informed consent is waived.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Liu, F., Wang, L. et al. Effect of systematic nursing on scar appearance following radical thyroidectomy: a retrospective cohort analysis. Sci Rep 15, 29235 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06419-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06419-6