Abstract

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head affects young adults, often requiring THA due to compromised blood supply and hip pain. To assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) regarding avascular necrosis in patients. A cross-sectional study was conducted from May 16 to June 19 at Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University. A total of 933 patients diagnosed with osteonecrosis of the femoral head were recruited. Demographic data were collected, and KAP was assessed through self-designed questionnaires comprising 11 knowledge items (scored 11–55), 8 attitude items (scored 8–40), and 10 practice items (scored 10–50). A total of 933 valid responses were obtained, with 743 (79.6%) being male. Mean KAP scores were: knowledge 34.54 ± 5.19 (range: 11–55), attitude 29.38 ± 5.10 (range: 8–40), and practice 36.82 ± 8.64 (range: 10–50). Item analysis revealed that patients showed positive attitudes towards treatment compliance (89.4% agreeing with the importance of treatment adherence) but felt anxious about their condition (37.8% reporting high anxiety). Regarding practices, patients demonstrated good medication adherence but lower compliance with rehabilitation exercises and follow-up visits. Significant positive correlations were found: knowledge-attitude (r = 0.485, P < 0.001), knowledge-practice (r = 0.580, P < 0.001), and attitude-practice (r = 0.624, P < 0.001). Structural Equation Modeling indicated direct effects of knowledge on attitude (β = 0.466, P < 0.001) and practice, (β = 0.654, P < 0.001), with knowledge also affecting practice indirectly through attitude (β = 0.066, P < 0.001). Patients showed inadequate knowledge but positive attitudes and proactive practices regarding avascular necrosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

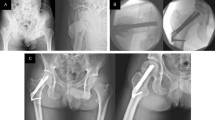

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head, a prevalent and challenging orthopedic condition, involves structural changes due to impaired blood supply, often leading to hip pain and early joint lesions. Annually, this condition accounts for 20,000–30,000 new cases worldwide1 and currently affects approximately 8.12 million individuals in China2. The progression of this disease is generally driven by factors such as trauma, alcohol abuse, extensive use of corticosteroids, organ transplantation, certain inflammatory or autoimmune diseases, sickle cell anemia, lipid metabolism disorders, and viral infections3.

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head primarily affects young adults, causing significant morbidity due to the disruption of blood flow to the femoral head and increased intraosseous pressure4,5. The therapeutic approaches for osteonecrosis of the femoral head include non-surgical methods and surgical interventions. Surgical treatments are categorized into joint arthroplasty and hip preservation surgeries. Joint arthroplasty, particularly effective in advanced stages and when secondary arthritis is present, has been widely validated for its effectiveness6. Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is recognized as a highly effective surgical option, affirmed through various studies7,8,9. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head can lead to rapid destruction and dysfunction of the hip, with approximately 65–70% of patients with advanced stages of the condition requiring total hip arthroplasty10. However, THA may lead to several complications, including postoperative prosthesis loosening, periprosthetic infection, and deep vein thrombosis11. Given the persistent challenges in treating this condition, it is crucial for patients to undergo regular follow-ups to evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment strategies implemented.

The Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) model suggests that individual behaviors are shaped by one’s knowledge and attitudes12. In public health, the exploration of behavioral practices frequently involves assessing both knowledge and risk perception, typically through KAP surveys. This approach is crucial for understanding how health-related behaviors unfold13. By examining the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of patients, significant insights can be gained into the efficacy of current educational and therapeutic strategies, thus identifying opportunities for healthcare providers to enhance patient outcomes. Despite the growing prevalence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head and its significant impact on young adults, there is a notable gap in the literature regarding patients’ understanding of the disease, their psychological responses to diagnosis, and their adherence to treatment recommendations. The KAP model is particularly valuable in this context as it provides a comprehensive framework for assessing not only what patients know about their condition but also how their knowledge influences their emotional responses and subsequent health behaviors. This is especially important for osteonecrosis of the femoral head, where treatment success heavily depends on timely intervention, appropriate lifestyle modifications, and strict adherence to therapeutic regimens14,15. Given the serious implications of this condition, including potential disability and the frequent necessity for major surgeries like total hip arthroplasty, understanding the interplay between knowledge, attitudes, and practices can inform targeted interventions to improve patient outcomes. Accordingly, this study was conducted to explore these dimensions among patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head, with the aim of identifying specific areas for educational and supportive interventions.

Methods

Study design and subjects

This cross-sectional study was conducted from May 16 to June 19 at the author’s hospital, focusing on patients diagnosed with osteonecrosis of the femoral head. The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the author’s Hospital, and informed consent was secured from all participants. Inclusion criteria included: (i) individuals aged 18–85 who were mentally alert, without communication barriers, and expressed willingness to participate; (ii) patients diagnosed with osteonecrosis of the femoral head for at least three months, including those who had undergone total hip arthroplasty; (iii) patients meeting the diagnostic criteria for osteonecrosis of the femoral head with a confirmed diagnosis, as per the "Expert Consensus on Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment Techniques for Osteonecrosis of the femoral head (2022)16." Exclusion criteria encompassed: (i) patients with advanced-stage tumors, active tuberculosis, or infectious diseases; (ii) individuals with intellectual disabilities. This study was conducted and reported in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for observational studies.

Questionnaire design and data collection

The questionnaire design was informed by the "Expert Consensus on Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment Techniques for Osteonecrosis of the femoral head (2022)16." Following its initial creation, the questionnaire underwent revisions based on feedback from five orthopedic subject matter experts specializing in joint surgery and was subsequently pilot-tested with 24 participants. During the pilot testing, we specifically assessed participants’ comprehension of questionnaire items, asking them to explain their understanding of each question to ensure clarity and relevance. Based on their feedback, we adjusted terminology, provided additional explanations for medical terms, and simplified complex questions to enhance understanding across different educational levels. To further ensure comprehension during data collection, various support mechanisms were implemented: patients in the ward and outpatient department had questions answered by the doctor on duty; patients who were followed up by telephone received explanations from doctors via phone; doctors were continuously available to answer questions in the WeChat group where questionnaires were collected; and for elderly patients, their children assisted in completing the questionnaire. The reliability of the questionnaire was confirmed with an overall Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.932.

The final version of the questionnaire, presented in Chinese (a version translated into English was attached as an Appendix), consisted of four sections: demographic information (including age, gender, education level, occupation type, income level, smoking and drinking habits, exercise, and duration of illness), and dimensions assessing knowledge, attitudes, and practices. The knowledge dimension comprised 11 items, rated from very knowledgeable (5 points) to very unknowledgeable (1 point), with a total possible score range of 11–55 points. The attitude dimension included 8 items on a five-point Likert scale, from strongly agree (5 points) to strongly disagree (1 point), yielding a total score range of 8–40 points. The practice dimension featured 10 items, scored from always (5 points) to never (1 point), with a total possible score of 10–50 points. Adequate knowledge, positive attitudes, and proactive practices were defined as scores exceeding 70% of the maximum possible score in each respective dimension17.

Data collection was facilitated using Questionnaire Star, and the researchers gathered contact information of previous patients via phone calls, WeChat groups, departmental bulletin boards, and outpatient visits. This approach enabled the distribution of the questionnaires to the intended study participants.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). SPSS 22.0 was selected for its comprehensive statistical capabilities and reliability in handling survey data. Appropriate parametric and non-parametric tests were applied based on data distribution. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were performed to explore the risk factors associated with K, A, and P, with 70% of the total score was used as the cut-off value. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized to explore the relationships between knowledge (K), attitude (A), and practice (P). SEM was specifically chosen for its ability to examine complex relationships between latent variables and to simultaneously test direct and indirect effects, which was essential for understanding how knowledge impacts practices both directly and through attitudinal changes. Model fit was evaluated using root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), incremental fit index (IFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and comparative fit index (CFI). A two-sided P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Initially, a total of 1002 samples were collected. Eleven cases with incorrect answers to the quality control questions and fifty-eight cases with an answer time of less than 90 s were excluded, resulting in a final valid data of 933 cases, with an effective rate of 93.11%. Of these, 487 (52.2%) were aged 50–64 years, 743 (79.6%) were male, 458 (49.1%) had high school education, 458 (49.1%) were manual labors, 439 (47.1%) had family’s monthly income of 5000–10,000 Yuan, 438 (46.9%) exercised for an average of 30–60 min per day in the past week, 461 (49.4%) diagnosed with femoral head necrosis for 2–5 years. Their mean knowledge, attitude, and practice scores were 34.54 ± 5.19, 29.38 ± 5.10, and 36.82 ± 8.64, respectively. Further analysis of demographic influences revealed notable patterns. Education level showed a consistent positive association with all three KAP dimensions (P = 0.002, P < 0.001, P < 0.001 respectively), with participants holding bachelor’s degrees or above scoring significantly higher (knowledge: 36.06 ± 4.44; attitude: 30.35 ± 5.12; practice: 39.49 ± 7.12) compared to those with high school education (knowledge: 33.91 ± 5.88; attitude: 29.09 ± 5.12; practice: 36.10 ± 9.06). Similarly, family monthly income demonstrated strong positive correlations with KAP scores (all P < 0.001), with participants in the highest income bracket (> 20,000 Yuan) showing superior knowledge (35.93 ± 4.26), more positive attitudes (31.35 ± 3.80), and better practices (39.91 ± 8.25) compared to those earning < 2000 Yuan (knowledge: 30.24 ± 8.23; attitude: 27.94 ± 4.98; practice: 30.19 ± 9.92) (Table 1). In addition, patients’ knowledge, attitude, and practice scores varied across total alcohol consumption in the past 30 days (P = 0.005, P = 0.005, P < 0.001), average daily exercise duration in the past week (P = 0.002, P < 0.001, P < 0.001), and duration of femoral head necrosis (P = 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001). Concurrently, patients’ knowledge scores were more likely to differ by work type (P < 0.001). Their attitude scores were more likely to differ by residence (P < 0.001) and smoking status (P = 0.042). Those with different gender (P = 0.035), residence (P = 0.018), work type (P < 0.001), and smoking status (P = 0.030) were more likely to have different practice scores (Table 1).

The distribution of knowledge dimensions shown that the three questions with the highest number of participants choosing the “Very uninformed” option were "MRI of the hip joint is the gold standard for diagnosing osteonecrosis of the femoral head." (K6) with 33.3%, "The treatment plan for osteonecrosis of the femoral head should comprehensively consider factors such as the patient’s age, the stage and type of bone necrosis, and adherence to joint-preserving treatment." (K9) with 31.9%, and "Treatment techniques for osteonecrosis of the femoral head" (K8) with 31.3% (Table S1). The responses to the attitude items showed that 35.6% always felt the pain caused by osteonecrosis of the femoral head in their daily life (A1), 37.8% felt very anxious and very afraid of the disease (A2), and 34.6% reported that the disease had very serious impacts on their work and life (A3). In addition, towards other treatment and care related items, about 10% of the patients had a negative attitude (choosing “disagree” or “strongly disagree”) (Table S2). When it comes to relevant practices, 12.3% seldom and 9.6% never undertake appropriate rehabilitation according to their condition (P10), 12.2% seldom and 8.9% never self-regulate to maintain a good state of mind (P19), and 11.6% seldom and 9.3% never undergo regular follow-ups (P7) (Table S3).

In the correlation analysis, significant positive correlations were found between knowledge and attitude (r = 0.485, P < 0.001), knowledge and practice (r = 0.580, P < 0.001), as well as attitude and practice (r = 0.624, P < 0.001), respectively (Table S4).

Multivariate logistic regression showed that with Bachelor’s degree or above (OR = 1.728, 95% CI [1.182, 2.525], P = 0.005), lived in urban (OR = 0.667, 95% CI [0.494, 0.902], P = 0.009), other work type (OR = 1.771, 95% CI [1.186, 2.646], P = 0.005), with family’s monthly income of more than 2000 Yuan (OR > 1, P < 0.005), consumed 30 bottles of alcohol in the past 30 days (OR = 0.700, 95% CI [0.502, 0.977], P = 0.036), and diagnosed femoral head necrosis for 5 years or more (OR = 1.599, 95% CI [1.001, 2.553], P = 0.049) were independently associated with knowledge. Meanwhile, knowledge score (OR = 1.252, 95% CI [1.203, 1.303], P < 0.001), lived in urban (OR = 0.528, 95% CI [0.378, 0.737], P < 0.001), consumed more than 30 bottles of alcohol in the past 30 days (OR = 0.449, 95% CI [0.268, 0.753], P = 0.002), and exercise for an average of more than 60 min per day in the past week (OR = 0.519, 95% CI [0.302, 0.891], P = 0.017) were independently associated with attitude. Furthermore, knowledge score (OR = 1.252, 95% CI [1.197, 1.309], P < 0.001), attitude score (OR = 1.089, 95% CI [1.053, 1.126], P < 0.001), manual labor (OR = 1.871, 95% CI [1.209, 2.895], P = 0.005), other work type (OR = 2.406, 95% CI [1.498, 3.863], P < 0.001), with family’s monthly income of 5000–10,000 Yuan (OR = 2.056, 95% CI [1.088, 3.884], P = 0.026), with family’s monthly income of more than 20,000 Yuan (OR = 2.987, 95% CI [1.293, 6.898], P = 0.010), consumed 30 bottles of alcohol in the past 30 days (OR = 0.403, 95% CI [0.231, 0.703], P = 0.001), diagnosed femoral head necrosis for 2–5 years (OR = 2.050, 95% CI [1.240, 3.390], P = 0.005), and diagnosed femoral head necrosis for 5 years or more (OR = 2.627, 95% CI [1.485, 4.648], P = 0.001) were independently associated with practice (Table 2).

The fit of the SEM model yielded good indices demonstrating good model fit (RMSEA value: 0.066, SRMR value: 0.077, TLI value: 0.879, and CFI value: 0.891) (Table S5), and the SEM results showed that the direct effect of knowledge on both attitude (β = 0.466, P < 0.001) and practice (β = 0.654, P < 0.001), as well as of attitude on practice (β = 0.141, P < 0.001), moreover, knowledge indirectly affected practice through attitude (β = 0.066, P < 0.001) (Table 3; Fig. 1).

Discussion

Despite inadequate knowledge, patients showed positive attitudes and proactive practices towards managing osteonecrosis of the femoral head. To further enhance patient outcomes, clinical interventions should prioritize educational programs that target increasing knowledge, which is strongly correlated with both attitudes and practices.

The study’s findings indicate a complex interplay of KAP towards osteonecrosis of the femoral head, revealing that despite inadequate knowledge levels, patients generally exhibit positive attitudes and proactive practices. This pattern of KAP outcomes aligns with previous research suggesting that higher motivation for self-management can often compensate for knowledge deficits, particularly in chronic disease contexts where patients gradually adapt their behaviors over time despite initial informational shortcomings18,19. The pattern of KAP outcomes in our study aligns with research on other chronic musculoskeletal conditions. A recent systematic review of KAP studies among patients with various orthopedic conditions found that despite knowledge deficits, patients often develop positive attitudes toward treatment over time, particularly when healthcare providers establish effective communication channels20. Regarding rehabilitation adherence, our results showing approximately 22% of patients seldom or never undertaking appropriate rehabilitation are consistent with a meta-analysis that reported non-adherence rates of 20–30% for prescribed physical therapy across musculoskeletal conditions21. These comparisons suggest that challenges in patient education and self-management transcend specific diagnoses, highlighting the potential for developing educational interventions that address common barriers to knowledge acquisition and behavioral change in orthopedic care.

Analyzing the relationships among KAP through correlation analysis, multivariate logistic regression, and SEM, the findings are consistent with the hypothesis that knowledge significantly influences both attitudes and practices, a relationship substantiated in numerous studies across different health contexts22,23. The SEM results highlighted not only the direct effects of knowledge on attitudes and practices but also indicated an indirect pathway through which knowledge influences practices via attitudes, reinforcing the cascading effect of knowledge enhancement on patient behaviors. Examining specific demographic and behavioral factors, the significant differences in KAP scores across various categories were strongly supported by the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Higher education levels were consistently associated with better knowledge, more positive attitudes, and improved practices, suggesting a need for tailored educational interventions for patients with lower educational attainment. These educational differences highlight the importance of developing simplified, accessible materials using plain language and visual aids for patients with limited education, potentially enhancing their understanding and engagement with treatment protocols. Similarly, the strong correlation between income levels and KAP scores indicates that socioeconomic factors play a crucial role in disease management. Patients with higher monthly family income demonstrated significantly better knowledge, attitudes, and practices compared to those in lower income brackets, suggesting that financial barriers may impede optimal care. Future interventions should consider providing subsidized care options and financial counseling for economically disadvantaged patients to improve their ability to engage in rehabilitation and follow recommended treatment protocols. Urban residents displayed better attitudes compared to their non-urban counterparts, potentially due to better access to health resources or more exposure to health education24,25, a finding supported by logistic regression results indicating urban residence as a predictor of positive attitudes. Interestingly, despite the importance of physical activity in managing avascular necrosis, the data did not show consistent differences in practices based on the average daily exercise duration, which may be explained by varying physical capacities and differing stages of disease among patients. This finding suggests that generic recommendations for physical activity might need to be tailored to individual patient capacities and disease stages to be more effective26,27.

In the knowledge dimension, survey responses indicate significant disparities in patient cognition, with notable deficiencies demonstrated in core knowledge domains such as the pathogenesis of osteonecrosis of the femoral head and imaging diagnosis. For instance, a substantial proportion of patients were uninformed about the role of MRI as the gold standard for diagnosis and the various treatment techniques available. This finding resonates with previous studies highlighting knowledge gaps in patient populations regarding disease-specific diagnostic and treatment modalities28,29. To address these gaps, targeted educational interventions could be developed, such as informational sessions led by healthcare providers, interactive online modules, and patient brochures that specifically address these poorly understood areas. Additionally, integrating educational content into routine clinical interactions might also help in reinforcing this knowledge30,31.

In the attitude dimension, although a majority of patients demonstrate cognitive awareness of avascular necrosis’s clinical significance and early diagnostic imperatives, ambivalence and noncompliance tendencies emerge prominently regarding post-diagnostic behavioral modifications. Similar studies have shown that while patients may understand the severity of their condition, translating this understanding into a positive attitude towards behavioral change remains a challenge32,33. To enhance attitudes, specifically towards lifestyle modification, more personalized counseling that aligns with individual patient lifestyles, motivational interviewing by healthcare professionals, and patient support groups could be effective. Such interventions should focus on the direct benefits of lifestyle changes, potentially increasing patient motivation34.

The practice responses demonstrate that although a substantial cohort of patients exhibits proactive engagement in preventive health behaviors, longitudinal adherence to such practices displays significant variability. This pattern is particularly pronounced in two critical domains: compliance with scheduled clinical surveillance and consistent implementation of therapeutic lifestyle modifications. This inconsistency can be partly attributed to a lack of sustained motivation and the absence of structured support systems35,36. To improve practices, establishing more frequent and structured follow-up appointments could help maintain patient accountability. Additionally, developing a patient-led support system, such as peer groups or buddy systems, can provide emotional and motivational support. Healthcare providers might also consider using mobile health technologies, which have been shown to enhance patient engagement and adherence through reminders and tracking tools37.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits the ability to infer causal relationships between knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Future research should consider longitudinal designs to better track how changes in knowledge affect attitudes and practices over time, potentially establishing stronger evidence for causal relationships. Second, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce response bias, as participants might have provided socially desirable answers or may not accurately remember past behaviors. To address this limitation, future studies could incorporate objective measures such as electronic medication adherence monitoring or analysis of medical records to validate self-reported behaviors. Third, the study was conducted at a single hospital, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other populations or settings with different socioeconomic or cultural backgrounds. Multi-center studies across diverse geographical regions and healthcare settings would enhance the external validity of findings and provide insights into regional variations in KAP among patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Fourth, the cross-sectional design precluded our ability to assess the dynamic effects of disease progression or treatment modalities on KAP outcomes. Additionally, comorbid conditions such as diabetes and osteoporosis may indirectly influence KAP levels by affecting patients’ health literacy, which warrants validation through prospective studies. Sixth, the skewed gender distribution (79.6% male) in our study may limit the generalizability of KAP scores. While the male predominance aligns with the epidemiological characteristics of ONFH—where established risk factors such as alcohol consumption and smoking contribute to non-traumatic osteonecrosis38—overrepresentation of one gender could obscure potential sex-specific differences. Future studies should adopt stratified sampling or gender-matched designs to validate these findings across balanced cohorts. Additionally, qualitative research methods such as in-depth interviews or focus groups could complement quantitative findings by providing deeper insights into the barriers and facilitators affecting patients’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices.

Conclusions

In conclusion, patients demonstrated inadequate knowledge, positive attitudes and proactive practices towards osteonecrosis of the femoral head. These findings underscore the need for targeted educational interventions that enhance patient understanding to further improve their attitudes and self-management practices. To optimize clinical outcomes, healthcare providers should integrate personalized education programs into routine care for patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head, particularly focusing on those with lower socioeconomic status and education levels. Specifically, we recommend: (1) developing multimedia educational materials that address identified knowledge gaps, especially regarding diagnostic techniques and treatment options; (2) implementing peer-support programs to enhance positive attitudes toward lifestyle modifications; (3) establishing structured follow-up systems with digital reminders to improve adherence to rehabilitation protocols; and (4) creating tailored interventions for vulnerable populations such as those with lower education levels and income. These targeted approaches may collectively improve disease management and patient outcomes for this challenging orthopedic condition.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- KAP:

-

Knowledge, attitudes, and practices

- THA:

-

Total hip arthroplasty

- SD:

-

Standard deviations

- SEM:

-

Structural equation modeling

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation

- IFI:

-

Incremental fit index

- TLI:

-

Tucker–Lewis index

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

References

Wells, M. E. & Dunn, J. C. Pathophysiology of avascular necrosis. Hand Clin. 38(4), 367–376 (2022).

Chinese guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head in adults. Orthop. Surg. 9(1), 3–12 (2017).

Hoogervorst, P., Campbell, J. C., Scholz, N. & Cheng, E. Y. Core decompression and bone marrow aspiration concentrate grafting for osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J. Bone Joint. Surg. Am. 104(Suppl 2), 54–60 (2022).

Boontanapibul, K. et al. Diagnosis of osteonecrosis of the femoral head: Too little, too late, and independent of etiology. J. Arthroplasty 35(9), 2342–2349 (2020).

Konarski, W. et al. Avascular necrosis of femoral head-overview and current state of the art. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(12), 7348 (2022).

Mont, M. A., Salem, H. S., Piuzzi, N. S., Goodman, S. B. & Jones, L. C. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: Where do we stand today?: A 5-year update. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 102(12), 1084–1099 (2020).

Capone, A., Bienati, F., Torchia, S., Podda, D. & Marongiu, G. Short stem total hip arthroplasty for osteonecrosis of the femoral head in patients 60 years or younger: A 3- to 10-year follow-up study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 18(1), 301 (2017).

Martz, P. et al. Total hip arthroplasty with dual mobility cup in osteonecrosis of the femoral head in young patients: Over ten years of follow-up. Int. Orthop. 41(3), 605–610 (2017).

Miladi, M., Villain, B., Mebtouche, N., Bégué, T. & Aurégan, J. C. Interest of short implants in hip arthroplasty for osteonecrosis of the femoral head: Comparative study “uncemented short” vs. “cemented conventional” femoral stems. Int. Orthop. 42(7), 1669–1674 (2018).

Cehelyk, E. K., Stull, J. D., Patel, M. S., Cox, R. M. & Namdari, S. Humeral head avascular necrosis: Pathophysiology, work-up, and treatment options. JBJS Rev. 11(6), e23 (2023).

Park, C. W., Lim, S. J., Kim, J. H. & Park, Y. S. Hip resurfacing arthroplasty for osteonecrosis of the femoral head: Implant-specific outcomes and risk factors for failure. J. Orthop. Translat. 21, 41–48 (2020).

Deng, Y. M., Wu, H. W. & Liao, H. E. Utilization intention of community pharmacy service under the dual threats of air pollution and COVID-19 epidemic: Moderating effects of knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(6), 3744 (2022).

Aerts, C. et al. Understanding the role of disease knowledge and risk perception in shaping preventive behavior for selected vector-borne diseases in Guyana. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14(4), e0008149 (2020).

Kuroda, Y., Matsuda, S. & Akiyama, H. Joint-preserving regenerative therapy for patients with early-stage osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Inflamm. Regenerat. 36(1), 4 (2016).

Mont, M. A., Cherian, J. J., Sierra, R. J., Jones, L. C. & Lieberman, J. R. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: Where do we stand today?: A ten-year update. JBJS 97(19), 1604–1627 (2015).

Association Related To Circulation Osseous Chinese Microcirculation Society C-A: [Expert consensus on clinical diagnosis and treatment technique of osteonecrosis of the femoral head (2022 version)]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 2022, 36(11), 1319–1326.

Hebo, H. J., Gemeda, D. H. & Abdusemed, K. A. Hepatitis B and C viral infection: Prevalence, knowledge, attitude, practice, and occupational exposure among healthcare workers of Jimma University Medical Center, Southwest Ethiopia. ScientificWorldJournal 2019, 9482607 (2019).

Hell, M. E., Miller, W. R., Nielsen, B. & Nielsen, A. S. Is treatment outcome improved if patients match themselves to treatment options? Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 19(1), 219 (2018).

Timmermans, L. et al. Self-management support in flemish primary care practice: The development of a preliminary conceptual model using a qualitative approach. BMC Prim Care 23(1), 63 (2022).

Goh, S.-L. et al. Efficacy and potential determinants of exercise therapy in knee and hip osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 62(5), 356–365 (2019).

Zhang, Z.-Y. et al. Digital rehabilitation programs improve therapeutic exercise adherence for patients with musculoskeletal conditions: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Therapy 52(11), 726–739 (2022).

Bekele, H. T., Nuri, A. & Abera, L. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward cervical cancer screening and associated factors among college and university female students in dire Dawa City, Eastern Ethiopia. Cancer Inform. 21, 11769351221084808 (2022).

Kim, B. J., Kim, S., Kang, Y. & Kim, S. Searching for the new behavioral model in energy transition age: Analyzing the forward and reverse causal relationships between belief, attitude, and behavior in nuclear policy across countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(11), 6772 (2022).

Negesa, L. B., Magarey, J., Rasmussen, P. & Hendriks, J. M. L. Patients’ knowledge on cardiovascular risk factors and associated lifestyle behaviour in Ethiopia in 2018: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 15(6), e0234198 (2020).

Zhang, Q. N. & Lu, H. X. Knowledge, attitude, practice and factors that influence the awareness of college students with regards to breast cancer. World J. Clin. Cases 10(2), 538–546 (2022).

Alley, S. J. et al. Engagement, acceptability, usability and satisfaction with Active for Life, a computer-tailored web-based physical activity intervention using Fitbits in older adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 20(1), 15 (2023).

Gorny, A. W., Chee, W. C. D. & Müller-Riemenschneider, F. Active use and engagement in an mHealth initiative among young men with obesity: Mixed methods study. JMIR Form. Res. 6(1), e33798 (2022).

Kaye, D. K. Navigating ethical challenges of conducting randomized clinical trials on COVID-19. Philos Ethics Humanit. Med. 17(1), 2 (2022).

Singh, S. et al. Clinical prediction of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) via anthropometric and biochemical variations in Prakriti. Diseases 10(1), 15 (2022).

Lamb, J. N., Holton, C., O’Connor, P. & Giannoudis, P. V. Avascular necrosis of the hip. BMJ 365, l2178 (2019).

Teimouri, M., Motififard, M. & Hatami, S. Etiology of femoral head avascular necrosis in patients: A cross-sectional study. Adv. Biomed. Res. 11, 115 (2022).

Benbelkacem, S. et al. Tumor lung visualization and localization through virtual reality and thermal feedback interface. Diagnostics (Basel) 13(3), 567 (2023).

Yang, T. et al. The impact of using three-dimensional printed liver models for patient education. J. Int. Med. Res. 46(4), 1570–1578 (2018).

Koerner, M., Westberg, J., Martin, J. & Templeman, D. Patient-reported outcomes of femoral head fractures with a minimum 10-year follow-up. J. Orthop. Trauma 34(12), 621–625 (2020).

Bao, H. Effects of messaging framing on the self-management activities and self-efficacies of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Iran. J. Public Health 52(6), 1248–1258 (2023).

Choi, W. & Lee, U. Loss-framed adaptive microcontingency management for preventing prolonged sedentariness: Development and feasibility study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 11, e41660 (2023).

Coles, T. M., Wilson, S. M., Kim, B., Beckham, J. C. & Kinghorn, W. A. From obligation to opportunity: Future of patient-reported outcome measures at the Veterans Health Administration. Transl. Behav. Med. 9(6), 1157–1162 (2019).

Liu, W., Yue, J., Guo, X., Wang, R. & Fu, H. Epidemiological investigation and diagnostic analysis of osteonecrosis of the femoral head in three northeastern provinces of China. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 19(1), 292 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guangnian Liu carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. Chengqi Huang and Xing Chen performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. Zhitong Zhu and Liming Dong participated in acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University (KLL-2024–086). The study was carried out in accordance with the applicable guidelines and regulations.

Informed consent

All participants were informed about the study protocol and provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, G., Huang, C., Zhu, Z. et al. Knowledge, attitude, practice, and influencing factors among patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Sci Rep 15, 22899 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06604-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06604-7