Abstract

Life events are noteworthy moments that we often share on social media. However, how such online disclosures of life events impact our mental wellbeing is largely unknown. This study examines the effects of these disclosures using data from 236 participants. Regression models reveal that individual differences and event attributes significantly influence wellbeing. Through a quasi-experimental design, we find that sharing life events on Facebook positively impacts wellbeing by increasing positive affect and sleep quality while reducing negative affect, stress, and anxiety. Notably, disclosing negative events shows the strongest improvement in wellbeing, suggesting a protective effect of social media. Additionally, life event disclosures elicit more reactions and comments than other Facebook posts, with negative events receiving more comments but fewer reactions than non-negative life event disclosures. These findings offer insights into the complex relationship between online disclosures and wellbeing, contributing to theoretical understanding and practical strategies for enhancing online experiences and supporting mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

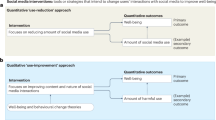

Our lived experiences unfold along non-linear paths marked by inevitable ups and downs. These fluctuations are punctuated by life events—noteworthy changes in our social or personal circumstances that can potentially alter our psychophysiology and behaviors1,2. By definition, life events—whether positive or negative, personal or collective—can disrupt our daily routines and impact our behaviors, emotions, and wellbeing, both in the short- and long-term. At the same time, the rise of digital and social media platforms has transformed how we process and share these experiences. Life event disclosures are a unique social media activity that straddles an individual’s context across their offline and online worlds. We often share our life events on Facebook, X (Twitter), Instagram, and other emerging popular social media platforms3. These platforms also have explicit affordances encouraging us to record and archive our life events. For example, the Facebook timeline reminds us of birthdays and personal milestones, such as getting married, starting a new job, or moving to a new place. Prior research has studied social media disclosures of sensitive life events, such as gender transitions4, death of a loved one5,6, child birth7, job loss8, and pregnancy loss9, and the choices between disclosure and non-disclosure of life events on social media3,10,11. However, the effects of such disclosures on our wellbeing remain underexplored.

Interestingly, there is contrasting evidence about the impact of social media use on mental wellbeing—both detrimental and beneficial. On the one hand, excessive screen-time and addiction to social media have been associated with adverse mental health outcomes12,13. The addictive nature of social media platforms— characterized by distracting notifications and a constant need for social validation—can further exacerbate stress and mental health14. O’Reilly et al.15 identified three themes in terms of the negative effects of social media in youth and adolescents: 1) links to mood and anxiety disorder, 2) risk of cyberbullying, and 3) addictive use patterns. However, this evidence is not univocal—a longitudinal study spanning eight-years with 500 adolescents found no significant relationship between increased social media use and deteriorating mental health outcomes16.

On the other hand, research has also revealed the therapeutic potential of social media in improving mental wellbeing17,18, decreasing loneliness19, and increasing life satisfaction20. These platforms enable stigmatized and sensitive self-disclosures21. Disclosing emotionally meaningful experiences online has been linked to emotional release, increased self-acceptance, and solidarity with others22,22,24. Prior work has also recognized social media as a mental health intervention through self-disclosure, peer support, and self-reflection opportunities25,25,27. In particular, Naslund et al.28 highlighted the key benefits and challenges of social media platforms for individuals with lived experiences of mental health conditions—while the benefits include facilitation of social interactions, peer support networks, engagements and retention in services, the challenges include risk on symptoms, hostile interactions, and consequences28.

Beyond these mixed findings, scholars have pointed out methodological limitations in existing research, which often relies on cross-sectional data and retrospective self-reports29,30. Further, much research has focused on aggregated metrics such as screen time or platform use, without fully accounting for the diversity of behaviors that can occur within these interactions. As a result, we know relatively little about what actually happens during screen time. Yet, to better understand social media’s impact on wellbeing, it is critical to look “under the hood”—at what individuals do during their time online, especially the nature and content of their posts, which can widely vary in psychological significance. One such behavior, disclosure of personally meaningful life events, is common but remains understudied. These disclosures are qualitatively different from routine updates or casual interactions—they often involve emotional vulnerability, identity exploration, or moments of personal significance3. A lingering question that persists: Are social media platforms conducive environments—from a mental wellbeing perspective—for disclosing personally meaningful life experiences?

Accordingly, it is crucial to understand the interplay between offline life events, online disclosures, and an individual’s psychological health. This is also important from a behavioral health perspective, as life event occurrences are often overlooked when in mental health assessments using digital behavioral data. Failing to account for these events can result in biases and inaccuracies in real-world predictions of mental health. This paper aims to address the question, How does disclosing a life event on social media impact an individual’s mental wellbeing?

We conducted our study within the scope of the Tesserae project31—a large-scale passive sensing research initiative where 236 participants shared their year-long Facebook data and also responded to periodic self-reported wellbeing surveys of positive and negative affect, stress, anxiety, and sleep. These participants also responded to an exit-survey—based on the PERI life event scale32—of their life event occurrences during the participant period. We adopted a quasi-experimental design based on the potential outcomes framework33 and difference-in-differences34 to examine the causal effect of self-disclosing life events on Facebook on wellbeing. We found that self-disclosing life events on Facebook positively impacts an individual’s wellbeing—increased positive affect and sleep quality, and decreased negative affect, stress, and anxiety.

Additionally, we conducted a deeper dive into understanding the effects of life event disclosures on Facebook. Regression models revealed that receiving engagement (reactions and comments) is positively associated with improved wellbeing. We further dissected Facebook life event disclosures by valence (negative, neutral, and positive life events), and aggregated the average treatment effects (ATEs), to find that Facebook disclosures provide the strongest ATEs in improving wellbeing in the case of negative events followed by neutral events, but no such significant change in the case of positive life events. This finding suggests that social media disclosures may have “protective effects” in the context of negative life events. We also examined the differences in reactions and comments to find that life event posts are likely to receive a significantly greater quantity of reactions and comments than other Facebook posts. Again, posts disclosing negative life events are likely to receive fewer reactions but more comments than neutral and positive life event posts. The differences in how other Facebook users engage on the life event disclosures can help explain the “protective efects” of social media.

Taken together, our work makes three key contributions. First, using a quasi-experimental design, we provide empirical evidence that life event disclosures, particularly of negative life events, can have protective effects on mental wellbeing. Second, we uncover how patterns of social feedback (reactions and comments) vary by event valence and are linked to wellbeing outcomes, offering insight into the social dynamics underlying these effects. Third, we advance a novel, context-sensitive perspective on digital wellbeing by centering our analysis on life event disclosures–a psychologically significant and previously underexamined form of social media engagement.

We discuss our work’s theoretical and practical implications in understanding the wellbeing impacts of life event disclosures. Our results can be interpreted through several theoretical lenses. Individuals’ use and disclosure on social media could be associated with the fulfillment of their psychological and social needs such as emotional expression and seeking social support, as per the Uses and gratifications theory35. Our findings support the therapeutic benefits of self-disclosure and expressive writing17,36—disclosing emotionally salient experiences on social media can foster intimacy and psychological relief. For example, when disclosing difficult events, individuals may be seeking empathy, validation, or reassurance, which could explain the observed improvements in wellbeing. The Social Capital Theory highlights how such disclosures may activate both bonding (strong ties) and bridging (weak ties) support networks—ranging from empathy to practical advice37. Furthermore, our findings that—negative life events when disclosed on Facebook could lead to improved wellbeing outcomes—support the Stress Buffering Hypothesis38, which posits that social support can mitigate the negative psychological effects of stressful life events. In our study, engagement (e.g., comments on life event posts) may act as a buffer that softens emotional distress. The Social Support Behavioral Code39 provides a lens to interpret the nature of this engagement, suggesting that supportive responses, particularly emotional or informational ones, are instrumental in improving perceived wellbeing following a disclosure. Taken together, these frameworks suggest that the act of disclosing a life event on social media is not merely an incidental online behavior, but serves as a mechanism for coping, connection, and seeking support. Accordingly, our work is a step towards offering informed interventions and recommendations for individuals, mental health professionals, and social media platforms about the potential benefits and risks of disclosing life events on social media. In conclusion, our study emphasizes the potential for digital platforms to serve as catalysts for positive psychological outcomes. By advancing theoretical understandings and informing practical interventions, our findings contribute to the ongoing dialogue at the intersection of digital technologies, social connectedness, and mental health.

Results

To examine how social media disclosures of life events impacted wellbeing changes, we needed to minimize confounds. We adopted a causal-inference design with the occurrence of a life event as the treatment and the changes in wellbeing measures as outcomes. We measured the effects over a two-week period after the life event. That is, for every Treated instance, we measured self-reported mental wellbeing in the two-week period after the occurrence of life event (After period) and compared that with self-reported wellbeing in the two-week period before the life event (Before period). To mitigate the confounds that these changes can be at random, we compared the outcomes in the Treated instances to counterfactual Control—how the individual’s wellbeing might have changed had they not been subjected to treatment (life event occurrence). Then, we operationalized the effects of the treatment on wellbeing outcomes by adopting a difference-in-differences strategy34. The Methods section elaborates our approach of curating our Treated and Control datasets, and measuring the treatment effects.

Quantifying the wellbeing impact of life event disclosures

To quantify how life event disclosures on Facebook impacted post− event mental wellbeing changes, we built regression models, where 1) for independent variables, we used individual differences (demographics and traits) and life event attributes (type, valence, intimacy, anticipation, status, scope, and significance), and 2) for dependent variables, we used the difference-in-differences (\(\mathtt {DiD_W}\)) of Treated and Control wellbeing (\(\texttt{W}\))—we built separate linear regression models for each of our wellbeing measures—positive affect, negative affect, stress, anxiety, and sleep quality.

Table 1 shows the results of the regression models We describe our observations below, per regression model—all of which show statistical significance in the goodness-of-fit (\(\mathtt {R^2}\), \(\texttt{p}\)<0.05). Our findings largely reveal that life disclosures on Facebook are associated with improved wellbeing—aligning with prior research on the benefits of self-disclosures on social media17,40,41.

Positive affect We find that Facebook disclosures bear a positive coefficient (0.12)—i.e., disclosing a life event on social media is associated with an increase in positive affect. In terms of life event attributes, health-related events are likely to decrease positive affect (-15.78). We note a positive coefficient for valence (0.91)—positive events are likely to increase positive affect, whereas negative events are likely to decrease positive affect. This observation aligns with the broaden-and-build theory42, which suggests that positive emotions can foster resilience and wellbeing. Among psychological traits, we find a negative coefficient for conscientiousness (-0.35) but a positive coefficient for neuroticism (0.55)—i.e., life events are likely to increase positive affect for individuals with high conscientiousness but decreased positive affect for individuals with high neuroticism.

Negative affect We find that disclosing life events on Facebook bears a significant coefficient (− 0.32) with changes in negative affect. The negative coefficient indicates that disclosing life events on Facebook is associated with a decrease in negative affect, indicating an improvement in wellbeing. This finding aligns with studies suggesting that social media disclosure can lead to emotional processing and social support, which help reduce negative emotions41,43. Among life event attributes, we see positive coefficients for life events related to health (5.65), personal (6.74), and work (5.92)—indicating that these types of life events are associated with an increase in negative affect. Also, the valence of a life event has a high negative coefficient (− 9.10), indicating that negative events are likely to increase negative affect, and positive events are likely to decrease negative affect. We also note positive coefficients for status (0.54), scope (0.31), and significance (9.99)—indicating that negative affect is likely to increase for continuous, individualized, and significant events. Among personality traits, we find that extraversion shows a positive coefficient (0.29), indicating that more extroverted individuals are likely to show increased negative affect after life events.

Stress First, we note a negative coefficient for social media disclosures (− 0.25), indicating that disclosing life events on social media is likely to decrease stress levels. For event attributes, we note a positive coefficient for health (6.18), personal (2.48), and work (1.83) related events. As in the case of negative affect, valence shows a negative relationship (− 2.66), indicating that negative life events are likely to increase the stress levels of individuals. Interestingly, the continuous status of events shares a negative relationship (− 0.16)—this could plausibly be associated with habituation in the stress response of individuals following life events44. We find a negative coefficient for openness (− 0.12) but a positive coefficient for extraversion (0.13), indicating that individuals with high openness are likely to be less stressed, and those with high extraversion are likely to be more stressed after a life event.

Anxiety We find similar signs of coefficients, like in the case of negative affect and stress, i.e., disclosing on social media (0.18) is likely to decrease anxiety. Among life event attributes, we find positive coefficients for health (5.99), personal (2.07), and work (1.50) related events but a negative coefficient for local (5.64) events. Again, valence (− 1.65) shares a negative relationship, and continuous status (0.21), scope (0.25), and significance (2.99) share positive relationships. Among personality traits, openness has a negative coefficient (− 0.18), and extraversion has a positive coefficient (0.16), i.e., extroverted individuals are likely to experience heightened anxiety after a life event. We note a weakly positive coefficient for trait negative affect (0.02).

Sleep quality Here again, social media disclosures show an improvement in wellbeing as indicated by the positive coefficient (0.20)—suggesting that disclosing life events on social media leads to better sleep. In fact, sharing personal experiences online may alleviate emotional burdens, promote social support, and reduce stress, which is critical for better sleep45. Contrastingly, prior work46 found that general social media use is associated with poorer sleep quality. However, we find that a specific kind of social media use—such as life event disclosures—may instead be linked to improved sleep quality, highlighting the nuanced effects of different online behaviors on wellbeing. For life event attributes, we note positive coefficients for health (1.36) and school (6.88) related life events. We note that continuous life events show a positive coefficient (0.57). Among personality traits, conscientiousness shows a positive relationship (0.20), indicating that individuals with high conscientiousness are likely to show better sleep after a life event. Again, trait anxiety shows a positive coefficient (0.05), and unsurprisingly, trait sleep quality (PSQI) shows a negative coefficient (-0.05)—the PSQI measure is reverse-coded (higher values indicating lower trait sleep quality).

Analyzing the causal effects on mental wellbeing

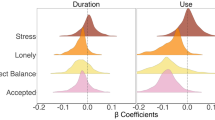

The above regression analyses reveal how life events impact individuals’ mental wellbeing, based on individual differences and life event attributes. Now, we break down this analysis further within individuals. Driven by the findings in Table 1, we break down the dimensions of disclosure on Facebook (yes/no) and the valence of life events (negative, neutral, positive). Table 2 reports the average treatment effect (\(\texttt{ATE}\)), effect size (Cohen’s \(\texttt{d}\)), and \(\texttt{t}\)-test for the changes in wellbeing measures for negative, neutral, and positive life events, and we describe the findings below:

Negative life events First, we look at life events that were not disclosed on social media. Based on effect sizes (Cohen’s \(\texttt{d}\)), we find that negative affect shows the highest Cohen’s \(\texttt{d}\)=0.19, with a positive ATE=0.36. This indicates the likelihood of an increase in negative affect following negative life events that were not disclosed on social media, supported by findings that online self-disclosure shows therapeutic effects on wellbeing17. In contrast, we find stark differences when negative life events are disclosed on social media. For instance, negative affect shows a statistically significant likelihood to decrease (\(\texttt{d}\)=-0.73, \(\texttt{t}\)=-4.93) with an \(\texttt{ATE}\)=-1.53. Similarly, stress (\(\texttt{ATE}\)=-0.42) and anxiety (ATE=-0.40) also show a statistically significant likelihood to decrease. The reduction of stress and anxiety aligns with the stress-buffering hypothesis for online self-disclosures of negative life event experiences22. We also note a positive \(\texttt{ATE}\)=0.57 and statistical significance (\(\texttt{ATE}\)=0.57, \(\texttt{d}\)=0.40) for sleep—indicating better sleep after disclosing negative life events on social media. These observations indicate the improvement of negative affect, stress, anxiety, and sleep following the disclosure of negative life events on social media.

Neutral life events When not disclosed on social media, neutral life events do not significantly impact wellbeing changes. However, when neutral life events are disclosed on social media, we see significant changes in negative affect, stress, anxiety, and sleep. In particular, disclosures are associated with wellbeing improvements in terms of a decrease in negative affect (\(\texttt{ATE}\)=-0.59), stress (\(\texttt{ATE}\)=-0.20), and anxiety (\(\texttt{ATE}\)=-0.23), whereas an increase in sleep quality (\(\texttt{ATE}\)=0.45).

Positive life events Similar to neutral events, when not disclosed on social media, positive life events do not significantly impact wellbeing changes. In addition, when disclosed on social media, we do not find any statistical significance for the wellbeing measures, as revealed by low ATE, Cohen’s \(\texttt{d}\), and t-test (\(\texttt{p}\)>0.05). This could be because Facebook already has a positivity bias47, and positive life event disclosures might be perceived as normative rather than exceptional. As a result, their emotional impact may not significantly enhance wellbeing because they do not stand out enough or for long, and the feedback received might feel obligatory, dampening the wellbeing effect48. Further, positive life event disclosures on social media can unintentionally evoke social comparison; individuals may downplay their happiness when they compare positive experiences to those of others, neutralizing potential benefits49.

Together, these findings indicate that disclosing life events (especially negative and neutral events) can lead to an improvement in terms of decreased negative affect, stress, and anxiety, and better sleep.

Post-hoc: responses to life event disclosures on Facebook

When someone shares a post on social media (e.g., Facebook), others can interact with it in various ways, such as reacting or leaving comments. In this regard, we examined the engagement received on life event disclosures. This would also help us explain how social media disclosures of life events lead to improved wellbeing outcomes, which we found in the previous section. We measured the responses received in terms of the engagement (reactions and comments) received. First, we built regression models to understand the relationship between engagement received and wellbeing outcomes. Then, we examined the differences in responses to Facebook posts disclosing life events from other posts. Finally, within life event disclosures, we examined the differences in responses to disclosures of varying valence (negative, neutral, and positive).

Social media engagement and wellbeing

Within the Facebook dataset of identified life events disclosures, we examined the relationship between received engagements and wellbeing. We built regression models for each wellbeing outcome (dependent variables) using individual attributes, life event attributes, and the number of reactions and comments received on life event disclosure posts as independent variables. Table 3 shows the results of the regression models. These models show significant \(\mathtt {R^2}\) (0.35 for positive affect, 0.60 for negative affect, 0.45 for stress, 0.44 for anxiety, and 0.26 for sleep).

We look at the engagements received on life event disclosures shared on Facebook and their association with wellbeing. Among the statistically significant measures (\(p<\)0.05), we observe that the number of reactions received is positively associated with positive affect (0.01) and negatively associated with negative affect (-1.7E-3), stress (-1.7E-3), and anxiety (-1.0E-4). Further, the number of comments received is positively associated with both positive affect (3.4E-3) and sleep (4.2E-3) but is negatively associated with anxiety (-1.0E-4). As previously noted, an increase in positive affect and sleep, and a decrease in negative affect, stress, and anxiety, signifies an improvement in wellbeing. These regression models, therefore, suggest that higher engagement levels on life event disclosures are generally associated with enhanced wellbeing outcomes.

Life event disclosures vs. other posts

Next, we compared the engagements received on posts with life event disclosures and other posts for the same individuals by obtaining the effect size (Cohen’s \(\texttt{d}\)), paired t-tests, and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. This would reveal if life event disclosures are likely to receive significantly different engagement than other Facebook posts. Table 4 reports the differences—we find that posts disclosing life events receive 132% higher reactions and 135% higher comments than the other posts. This is plausibly because life event self-disclosure posts could foster a sense of connection and intimacy among viewers, tending them to engage with the post50.

Life event disclosures varying in valence

Now, within life event posts, we examined the responses. Given that valence is a major attribute of life events that is also associated with wellbeing outcomes, we compared the responses to negative, neutral, and positive life event posts.

Similar to the above, we obtained the number of reactions and comments separately for negative, neutral, and positive life event posts. We conducted the Kruskal-Wallis test to obtain the statistical significance in the differences, as reported in Table 5. We observed an interesting contrast in terms of likes and comments—1) for reactions, negative life event posts received a mean 11.25 reactions, which is significantly lower than neutral (25.93) and positive (22.53) life event posts; however, 2) for comments, negative life event posts received a mean of 9.18 comments, which is significantly higher than neutral (3.52) and positive (3.38) life event posts. This indicates that the Facebook audience is more likely to respond to negative life event posts with comments rather than reactions compared to other life event posts.

Discussion

Principal findings

Our findings revealed multifaceted insights into the effects of disclosing life events on social media on mental wellbeing. We found that life event occurrences are strongly associated with mental wellbeing, including affect, stress, anxiety, and sleep quality. Our regression analyses revealed that both individual differences and life event attributes are significantly associated with an individual’s wellbeing outcomes. We found that disclosing life events on Facebook had a predominantly positive impact on individuals’ wellbeing. This was evidenced by increased positive affect and sleep quality, as well as decreased negative affect, stress, and anxiety following disclosures. Notably, by dissecting life events by different valence, we found that Facebook disclosures exhibited the strongest effects in improving wellbeing in the case of negative events. This suggests that social media platforms may help foster resilience and coping mechanisms, particularly in response to adverse disruptions in life. The following paragraphs discuss the implications of our work.

A nuanced look at the role of social media for mental health

This work contributes new and critical evidence on the mental health effects of social media use, a topic that has sparked significant public and academic debate. In recent years, social media platforms such as Facebook have been questioned by different governments over their negative effects51. The urgency of this issue is underscored by the recent U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy’s advisories on social media’s risks to mental health by recommending warning labels on platforms to notify users of the potential harms associated with usage52,53. They also issued another advisory emphasizing the need to reform online environments to combat the growing crisis of loneliness and social disconnection53. Much of the existing literature relies on screen time as a proxy for social media use, a measure that has been criticized for oversimplifying the complexities of online interactions. For instance, Haidt presented a critical narrative on the decline of youth wellbeing over the past 15 years, attributing much of this trend to the increasing ubiquity of digital and online interactions54. Although this work has drawn attention to the potential harms of social media, it has also faced criticism from scholars like Odgers55, who argued for a more nuanced understanding of how digital and online interactions influence wellbeing.

This paper examined a more nuanced social media activity—focusing on life event disclosures—rather than general measures of social media use (such as screen time). Our work found further support for social media engagement in the form of reactions and comments, as also noted in prior work on social media use, both generally37,56, as well as for sensitive self-disclosures9,17,21,57. Therefore, this work offers a novel approach to examining social media use by characterizing life event disclosures, prompting a new methodological advancement in this area of research.

Through a deeper investigation of specific social media activities, our findings underscore the benefits of social media, which are often overlooked in public discourse dominated by its potential harms. Our work paints a more complex picture of the role of social media use—social media’s harms must be considered in the context of its potential benefits. This viewpoint is also echoed in a recent article58—platforms can facilitate meaningful social connections and provide emotional support through features that encourage life event disclosures and foster supportive interactions. Importantly, our findings should also be interpreted in light of individual differences in disclosure behavior. For instance, individuals with high extraversion and agreeableness could be more likely to disclose life events on social media3, suggesting that disclosure is not uniform across users. This aligns with theories of self-presentation59, where social media posts serve expressive and social functions shaped by individual traits. While our study examined the effects of disclosure and engagement on wellbeing, these behaviors may reflect underlying personal traits. This inspires future research into how disclosure tendencies influence the impact of online support and whether tailoring interventions by psychological traits could enhance effectiveness.

Furthermore, while it is essential to acknowledge and address the risks associated with social media, such as privacy breaches, cyberbullying, and exposure to toxic behaviors60,60,62, it is also important to recognize the positive and protective effects social media can offer. For instance, platform features like reactions, comments, and sharing can enhance wellbeing by promoting connection, validation, and social support. Our findings can inspire the design of interventions and platforms that amplify these benefits, potentially counteracting broader trends of loneliness and social disconnection53, reinforcing a need for balanced and thoughtful approaches that address both the potential risks and benefits of social media engagement.

Integrating offline events with online data in digital mental health research

A majority of technology-driven mental wellbeing measurements fail to encompass a spectrum of human experiences beyond what is directly captured through the technology. For instance, conventional social media studies typically rely exclusively on people’s online behaviors to assess mental wellbeing, overlooking the substantial impact of offline factors on mental health outcomes63,64. Such data could be biased because they often capture only a fragment of human experience or may not fully represent the individual’s reflective emotional state. Disregarding the (offline) facet can lead to skewed conclusions that fail to account for critical offline events that may significantly impact an individual’s mental health. For instance, an algorithm solely based on social media data may fail to capture life events an individual did not disclose—and we know from prior work3 and this research that not every life event is disclosed by everyone on social media. Therefore, incorporating offline events and other data sources can help reduce biases in research findings. Our findings bear implications for research on human behaviors, emphasizing the importance of considering life events in predictive modeling of behaviors and wellbeing. These factors are often overlooked but prove crucial in understanding human dynamics, especially mental wellbeing.

In addition, online engagement can be influenced by multiple external variables, including social norms (e.g., only sharing positive content) or platform-specific affordances (e.g., algorithms amplifying certain types of interactions). This may lead to positivity bias47 in the data, where the absence of negative disclosures, due to self-censorship or privacy concerns may give an incomplete picture of mental wellbeing. Importantly, offline factors, such as personal crises, transitions, or successes, often carry emotional and psychological weight that is not always reflected in online behavior. In fact, the Life Course Theory65 emphasizes the role of significant life events (e.g., marriage, job loss, illness) in shaping individuals’ mental health across time—the trajectory component of this theory argues a cumulative impact of life experiences on future health and wellbeing. Consistent with this theory and as highlighted in our work, life events significantly influenced mental wellbeing outcomes, and if only online data is considered, models risk omitting these influential offline events. By integrating offline life event data (self-reports, surveys, interviews), we demonstrate that researchers can better capture the diverse factors contributing to mental health, reducing data bias and allowing a more nuanced understanding of wellbeing.

Moreover, the presence of supportive online engagement—such as comments in response to life event disclosures—may not reflect a purely online phenomenon. Individuals who receive such support may already have stronger offline social networks, which can shape both their likelihood of disclosing events and their psychological outcomes. Prior studies have shown that offline connectedness often correlates with more visible and supportive online interactions41,56, making it difficult to isolate the causal role of online engagement alone. Although we controlled for several baseline psychological traits, we did not have direct measures of participants’ offline support, which presents an important direction for future work. Integrating mixed-methods approaches—such as interviews or offline support surveys—would enable a more comprehensive disentanglement of the interplay between online and offline support systems in shaping wellbeing.

Including offline events in digital mental health research offers additional benefits. Quasi-experimental designs, such as those used in this paper, allow for causal inferences about how life events impact wellbeing. Our approach highlighted that the act of disclosing offline life events on social media is associated with changes in mental wellbeing, suggesting that digital platforms may serve as both amplifiers of and buffers against stress. This approach of triangulating between data sources can significantly mitigate additional biases associated with reliance on a single data stream66,67. Therefore, by considering both online and offline aspects of individuals’ lives, we provide a more comprehensive understanding of how various factors contribute to mental wellbeing in the digital age.

That said, integrating offline and online datasets presents significant challenges, particularly due to the sensitive nature of personal social media data and the technical limitations posed by the restricted availability and functionality of social media data APIs. One potential approach is participant-driven data collection—such as in Tesserae project31—where individuals voluntarily shared their social media data through privacy-preserving tools. These approaches can be coupled with data donation approaches with appropriate consenting practices68. Further, collaborations with social media platforms can also enable better access to anonymized user data, facilitating large-scale studies while maintaining confidentiality and best research practices. Importantly, such collaborations are also in the best interests of social media platforms, as it is their inherent responsibility to ensure the safety and wellbeing of their users—and also help them address the recent criticism about the social media platforms in accounting for user safety51. Additionally, researchers can employ ethnographic or diary methods, asking participants to document significant offline experiences alongside corresponding social media disclosures. While the datasets used in this study are novel and rare, these strategies offer pathways to overcome barriers in data collection, emphasizing the importance of ethical practices and participant privacy.

Theoretical implications: protective effects of social media

Self-disclosure and intimacy

Within our dataset, our findings contrast assumptions regarding the potential risks associated with online self-disclosures and rather reveal the positive impact of social media disclosure on wellbeing, particularly in the context of negative life events. Thereby, this work supports prior work on the positive effects of self-disclosures, such as the therapeutic effects of intimate self-disclosures69,70. Our findings align with Uses and Gratifications Theory, which posits that individuals actively engage with media platforms to fulfill psychosocial needs such as emotional expression, validation, and a sense of belonging35. In parallel, Social Capital Theory37 provides a valuable lens to understand how life event disclosures on social media can activate social resources that contribute to improved wellbeing outcomes.

We found that sharing negative experiences and disclosures can elicit strong and beneficial responses, potentially leading to therapeutic mental wellbeing outcomes. This finding sparks an intriguing conundrum regarding the dynamics of social media interactions when compared to previous research. For instance, Kramer et al. found that emotional states could spread among users through “emotional contagion” on Facebook, suggesting that exposure to negative posts could inadvertently evoke sadness in users without their conscious realization71 and Burke et al. found a tendency for normative Facebook use to exhibit a positivity bias47. Therefore, while negative disclosures might induce sadness in others, paradoxically, sharing such experiences could potentially improve the poster’s mental wellbeing. A variety of underlying mechanisms could explain this observation, which needs further theoretical investigation. Leaning on the narrative identity theory72, it is possible that an act of disclosing deeply personal life events on social media platforms may help individuals construct and maintain a coherent narrative identity, contributing to a sense of purpose and improved mental health.

Empathy and social support

Our findings are consistent with the stress-buffering hypothesis, where online self-disclosure acts as a relief mechanism, reducing the emotional burden of stressful experiences22,73—grounded in self-disclosure benefits from social science research73. By venting or disclosing life event experiences, individuals may experience a cathartic effect, helping to alleviate the immediate distress tied to those events74. People with strong social networks—friends, family, or community—are likely to experience less severe negative wellbeing consequences compared to those without these resources. The fact that disclosing life events on Facebook improves wellbeing outcomes may indicate that the protective effects of social networks may be present in online contexts as well. Social media platforms enable individuals to experience a sense of belongingness and emotional connection in response to life event disclosures that may help their wellbeing. In that sense, our work adds to the body of evidence that demonstrates the positive role that social media platforms may play when it comes to mental wellbeing75. Our findings provide support that social media disclosures can help towards the buffering effect of coping with negative life events76,77. Further research can examine the nature and extent of these protective effects of social media in response to life event disclosures.

Wellbeing effects of social media engagement

Further, our analysis on the differential responses to life event disclosures on Facebook provides insights into the mechanisms underlying the observed protective effects. The greater quantity of received engagement (reactions and comments) to life event posts than other posts, and greater comments specifically to negative life events, highlight the role of social media as a platform for interpersonal connection and social support during times of distress. Prior work developed theoretical frameworks on sensitive disclosures on social media, such as the disclosure-decision-making framework of what people choose (not) to disclose9. Our work empirically informs these frameworks by adding the dimension of how these disclosures and responses also benefit the individuals’ mental wellbeing.

Importantly, while our study focuses on short-term (two-weeks) changes in wellbeing following life event occurrences and corresponding Facebook disclosures, the long-term impacts of repeated disclosure on mental health remain an important area for future research. Repeated sharing can lead to cumulative benefits, such as ongoing emotional regulation, normalization of stigmatized conversations, or strengthened digital support networks. However, there may also be risks, such as heightened dependency on online validation or increased emotional exposure. Further longitudinal and between-subjects examinations are needed to examine how sustained disclosure behaviors can impact wellbeing trajectories over time.

Design implications: towards online platforms that prioritize and support mental wellbeing

From a design standpoint, our findings carry implications for social media users and platforms alike. A key takeaway from our study, albeit seemingly trivial, includes the entanglement of people’s online and offline lives. Our results highlight the potential benefits of encouraging sensitive self-disclosure on social media platforms, particularly in response to life events. These insights can be leveraged to incorporate social media interventions into therapeutic practices and recommendations to deal with major life events, providing additional avenues of support. Our findings provide support to research on expressive writing that has revealed healing effects on individuals undergoing difficult and traumatic life events36,78, and how social media can offer such a writing- or journaling-based self-reflection opportunity towards enhanced mental wellbeing79,80. Accordingly, platforms can adopt strategies that encourage more expressive writing and self-disclosure81,82.

This work underscores the importance of designing social media platforms that prioritize user wellbeing. It is important to note that Facebook, by design, typically limits the reach of a post within a “controlled audience”—within the friends circle of the individual. It would be interesting to see how these findings translate into other platform designs, such as a broadcasted public audience (e.g., on Twitter) or a closed community of interest (e.g., on Reddit). Prior research notes how platforms such as Reddit facilitate features like pseudonymity and community-driven moderation, which enable candid self-disclosures about stigmatized concerns21,40. This study contributes to the body of literature in understanding the effects of platforms’ design affordances and mental health15,75, and prompts further research into this space in exploring how specific design features may directly impact an individual’s wellbeing.

Our study highlights the value of platform affordances that facilitate social support and validation, amplifying the positive impact of sharing personal experiences. Designing features that enable users to selectively share posts with specific subsets of their social network could help tailor audiences more likely to respond supportively. Also, the advent of LLMs can inspire the building and evaluation of features such as personalized reaction buttons or comment prompts, encouraging empathetic and validating responses that could contribute to a more positive social environment. By understanding the nuanced effects of life event disclosures on user experiences, platform developers can enforce policies and guidelines to not only mitigate potential harms but also enhance supportive interactions. For instance, social media platforms primarily implement policies and punitive approaches based on limiting, moderating, and addressing toxic and antisocial behaviors, but it is equally important in promoting positive discourse and pro-social behaviors83,84. This work reinforces the need for such a balance, showing the positive impact of sensitive self-disclosures on mental wellbeing.

Along similar lines, this work indirectly opens up interesting discussions on algorithmic ranking and wellbeing effects. Social media platforms’ ranking algorithms often prioritize content that drives engagement85. Prior work86 highlighted that algorithmic prioritization can amplify certain narratives while silencing others—therefore, deeply personal disclosures may be overlooked in favor of content deemed more engaging by the platform’s algorithm. This can limit the visibility of an individual’s life event disclosure, reducing opportunities for social support—a key benefit of self-disclosure17,74,87. Addressing this requires rethinking algorithms to value the emotional and contextual significance of content alongside engagement metrics.

Ethical implications

Given the sensitive nature of this work, it is imperative to acknowledge and address potential ethical considerations surrounding studying individuals’ personal experiences, particularly in relation to mental health and social media disclosure. We recognize that life events, by their very nature, can evoke deeply personal emotions and vulnerabilities. As such, the ethical implications of our work extend beyond academic discourse to encompass the wellbeing and privacy of the individuals involved in the study. For instance, it is essential to recognize the potential negative societal implications that may arise from our findings. One concern is perpetuating or reinforcing societal stereotypes or stigmatization associated with certain life events. For instance, the observation of the differential responses to positive versus negative life events may inadvertently reinforce stereotypes or expectations about what happiness and adversity should look like on social media.

Another ethical implication pertains to the potential misuse of our findings. While our study highlights the positive impact of social media disclosure on mental wellbeing, there are risks of exploitation or manipulation by bad actors or entities seeking to capitalize on people’s vulnerabilities, such as targeted advertising based on disclosed life events or algorithms aimed at exploiting emotional vulnerabilities for commercial gain.

Again, while our work demonstrates the potential benefits of life event disclosures on social media, it is critical to also address the risks inherent in such disclosures. For instance, not all audiences on social platforms are supportive; hateful or unsupportive engagement can exacerbate stress and emotional harm88,89. Furthermore, disclosing negative experiences can also inadvertently encourage negative social comparisons, a phenomenon found to be detrimental to mental health49,90. These risks challenge the assumption that encouraging more disclosure is universally beneficial. Instead, future designs should carefully weigh the trade-offs, incorporating safeguards to mitigate risks while fostering supportive interactions. Overall, platforms need to be carefully designed to encourage self-disclosure, but also prevent inadvertent harms.

To mitigate these ethical concerns, adhering to stringent ethical standards and policies for research and practice is crucial. For social media research, obtaining informed consent from participants, ensuring confidentiality and anonymity, and safeguarding sensitive data against unauthorized access or misuse remain of paramount importance. It is critical to exercise caution in interpreting and disseminating findings, avoiding sensationalism or oversimplification of complex mental health issues associated with technology use. Further, our findings can help policymakers make informed decisions for regulatory frameworks that can protect individuals’ privacy rights and prevent the misuse of personal data for unethical purposes. Transparency and accountability in data collection, storage, and usage by platforms and third parties alike should be emphasized.

Visualization of the parallel trends assumption in wellbeing outcomes before and after intervention (life event occurrence as shown in the dotted line), and the x-axis shows days relative to the event. Note: the assessment of parallel trends is based on visual inspection, not formal statistical testing116.

Limitations and future directions

Our study has limitations, which also suggest interesting future directions. First, our study suffers from data and methodological limitations. Although our methodology was inspired by a quasi-experimental design, we cannot claim “true causality” due to the lack of counterfactual data. Combining our results with randomized experiments and between-subjects analyses will help provide a comprehensive understanding of the effects of life event disclosures on wellbeing. We acknowledge that our regression models may be subject to endogeneity concerns, given the potential bidirectional relationship between social media engagement (e.g., likes and comments) and wellbeing outcomes. While we controlled for baseline individual differences and psychological traits, unobserved confounders such as offline support systems may bias our estimates. Although the parallel trends assumption appears visually supported (Fig. 1), this is not a formal statistical test and should be interpreted with caution. More generally, the difference-in-diference approach is susceptible to underlying biases due to unobserved time-varying confounders. Additionally, engagement metrics, such as reactions and comments, are influenced by the number of friends on Facebook. However, because our dataset did not have the number of friends of each individual, we could not include this as a control variable in our regression models. Prior work has explored the complexity of engagement in health-related social media contexts, highlighting factors like message framing, perceived credibility, and audience receptiveness91,92. Moreover, Golder and Graham93 highlighted how content dynamics on platforms like Twitter complicate causal interpretation. Future work could incorporate longitudinal designs with lagged engagement variables, instrumental variable strategies, or matching techniques to better infer causal effects and disentangle the directionality of these associations.

Further, our study only examined with quantity of comments; however, as noted by94, quality of content bears a significant impact on the outcomes. Therefore, future research can also examine the content of comments for a better understanding. Additionally, while we considered interaction terms to capture more nuanced relationships, these terms were not statistically significant, leading us to favor simpler models for easier interpretation. Although we explored the effects of various life events, our study is limited in its ability to provide deeper insights into how specific types of life events impact individual well-being. Future research can build on Haimson et al.10’s work by focusing on the nuanced effects of specific life events. Additionally, more rigorous analyses of life event attributes are needed. For instance, our study lacked data to disentangle the effects of anticipation—the length of time an individual anticipates the occurrence of a specific event. Understanding whether prolonged anticipation amplifies or reduces stress related to the event will offer valuable insights. Likewise, our dataset assumes that the disclosure date of a life event aligns with its occurrence, as in prior work3, which may not always hold true—there can be a lag between an event’s occurrence and its disclosure. This limitation also applies in the case of self-reported survey data, which is susceptible to recall bias. Future research could integrate additional data sources to obtain a better-aligned and accurate representation of life events. More fundamentally, our study is not clinical in nature—we did not have access to participants’ baseline mental health conditions. Future work could incorporate standardized assessments, such as the PHQ-9, as well as offline psychosocial support information.

Fundamentally, although social media (Facebook) disclosures offer naturalistic, ecologically valid, in-the-moment insights that are self-initiated and contextually grounded, they may also be influenced by social desirability, platform norms, audience expectations, and selective self-presentation. As such, not all life events or emotional states may be equally represented in the data3. In addition, our study is limited to a single social media platform (Facebook), and we cannot claim generalizability to other platforms. Notably, the dataset used in our study was collected during 2018-19, with the latest posts dating back to 2019. On the one hand, this dataset is from a pre-COVID period, when several disruptions happened in both the offline and online lives of individuals; on the other hand, social media platforms continually evolve over time. For example, social media use has also transitioned from posting status updates for friends (on Facebook) or, more broadly (on Twitter), to sharing and consuming short-form videos, as seen on platforms like TikTok and Instagram. Life event disclosures can be in different modalities (such as via videos) or in comments. This opens up opportunities to examine other kinds of sensitive disclosures and their wellbeing effects in more modern use of social media for a holistic understanding. Our study also suffers from self-selection bias—we could only study individuals who agreed to participate and consented to share their data in the Tesserae project31. For more generalizable claims, future research can study more diverse populations with varying social media use. We acknowledge a limitation in our dataset’s lack of information for reaction types such as “likes”, “sad”, “angry”, “wow”, and “haha”. This limited us from exploring how social media audiences react differently to various life event disclosures. Further, our study did not have access to the content of comments from responders on Facebook posts. Future research can examine such comments in responses to provide further insight into what contributes to protective effects or improvements in people’s mental wellbeing. Importantly, future research can conduct time series explorations on the longer-term impacts of life events on wellbeing changes.

Methods

Study and data

This paper sourced its data from the Tesserae project31,95—a large-scale longitudinal project of studying wellbeing through multiple data modalities that recruited 754 participants. These participants were information workers in cognitively demanding fields in diverse job positions and roles (e.g., engineers, consultants, and managers) at various organizations across the U.S. The participants were enrolled between January 2018 and July 2018, and were asked to remain in the study for either up to a year or until April 2019.

Privacy and Ethics. The Tesserae project was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the lead institution, the University of Notre Dame, with reliance agreements at all participating research universities. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant institutional and national guidelines and regulations governing research with human participants. All members of the research team completed CITI (Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative) training in the ethical conduct of human-subjects research. The participants were provided with informed-consent documents, and consent was sought separately for each data modality. They could seek clarification and opt out of any data collection. During the consent and enrollment process, participants were explicitly informed that their involvement in the study did not require them to change their social media behavior in any way and that they could continue using social media as they normally would. The study was designed with a strong commitment to participant privacy and data security. All data used in the analysis were de-identified and stored on secure, encrypted servers.

Individual attributes

The participants provided self-reported data on demographics and psychological traits during enrollment in the Tesserae project. They responded to survey questions on demographics (e.g., age, gender, education, etc.), and psychological constructs: (1) Cognitive Ability assessed by the Shipley scales of Abstraction (fluid intelligence) and vocabulary (crystallized intelligence)96, (2) Personality Traits, the big-five personality traits as assessed by the Big Five Inventory (BFI-2) scale97, and (3) Wellbeing Traits, the general positive and negative affect levels as assessed by the Positive And Negative Affect (PANAS-X) scale98, the anxiety level as measured via State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)99, and the quality of sleep as measured via the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)100. Table 6 summarizes the dataset’s self-reported data distribution.

Self-reported daily wellbeing state measures

Participants also responded to daily and periodic surveys on wellbeing measures during the course of their participation period. These surveys consisted of short self-report surveys where participants responded to their immediate (state-level) wellbeing measures. These included: 1) Positive and negative affect measured by PANAS-Short101, 2) Stress as measured by a single-item omnibus question, “how do you rate your current level of stress?” on a scale of 1-5102,103, 3) Anxiety as measured by a daily single item instrument104 on a scale of 1-5, and 4) Sleep as measured by a single item MITRE scale measuring the total number of hours (0-24) of sleep in the previous day.

Social media data

The Tesserae project asked consented participants to authorize their social media data, particularly Facebook, unless they opted out or did not have an account31. The enrollment briefing and consent process explicitly explained that they were expected to continue with their typical social media use. Participants granted access to social media data through an Open Authentication (OAuth) based data collection infrastructure developed in prior work95. The OAuth protocol is an open standard, privacy-preserving, and convenient approach for data collection, enabling users to log in and grant third-party access to their data without sharing any personal credentials.

Among these, the total of 572 participants who provided access to Facebook data, 242 participants did not make any update during the year-long study period between January 2018 and April 2019—the same period when the participants’ self-reported life event occurrences were also collected. The remaining 330 participants made 14,202 posts during this study period—the data used by Saha et al.3 for studying life event disclosures on social media, which analyzed the relationship between individual and life event attributes, examining what life events are disclosed when, how, and by whom. The authors developed a codebook based on the PERI Life Events Scale to label and annotate life event attributes in social media disclosures3. Our work uses the dataset from this prior work with labels of life event disclosures and attributes in participants’ Facebook posts.

We particularly focus on the dataset by 236 participants who also responded to a life events survey (described in the next subsection). Figure 2 and Table 7 provide the distribution of the Facebook data—these 236 participants made a total of 12,397 posts ranging between 1 and 597 posts per individual (mean = 52.53, std. = 97.15). Each post received an average of 1.99 comments and 10.29 reactions.

The coding of life event disclosures was conducted in prior work3, where a rigorous multi-phase annotation process was followed to identify and categorize self-disclosed life events in Facebook posts. Five annotators from diverse cultural backgrounds (three women, two men; representing Caucasian, East Asian, and South Asian ethnicities) were recruited to account for the heterogeneity in participants’ cultural contexts. These annotators initially coded a random sample of 140 posts using the PERI Life Events Scale32, with the flexibility to introduce new categories for disclosures not covered by the original taxonomy. Discrepancies were discussed with two authors, and a refined codebook was developed to resolve boundary cases (e.g., distinguishing between “trip” and “vacation”). The annotators then independently coded an additional 50 posts, yielding an 88% agreement rate and an average Fleiss’ \(\kappa\) = 0.71, indicating substantial inter-rater reliability. For the remaining dataset (14,002 posts), two annotators coded posts independently, and given the subjectivity inherent in social media content, a liberal identification strategy was adopted—labeling a post as a life event disclosure if either annotator marked it as such. To support consistency, annotators referred to contextual cues across adjacent posts and followed jointly developed guidelines for ambiguous cases (elaborated in a codebook presented in Table 3 of Saha et al.’s work3).

Life events data

This paper uses life events data from two sources—1) Self-reported life events survey: the participants in the Tesserae project optionally responded to a life events survey at the end of the study. This survey was based on the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview (PERI) life events scale32. Out of the initial total of 754 participants, 423 participants responded to these surveys with 1,547 entries of life events during the study participation period (mean=3.86 events per individual). Among these 423 respondents, 236 provided their Facebook data. Prior work qualitatively coded the life event disclosures on 14,202 Facebook posts during the participation period, and built a codebook of social media disclosures of life events3. The coding was done analogous to the PERI life events scale, and each life event occurrence was labeled with the life event attributes. In particular, the authors formally defined a Facebook post to contain a life event, “if the post describes an event which is directly or indirectly associated with the individual or their close ones, such that it potentially leaves a psychological, physiological, or behavioral impact, or be significant enough to be remembered after a period.”3. We list and describe the life event attributes of the life event occurrences (on the PERI survey and Facebook):

Event type The PERI scale categorizes life events into six broad types—School, Health, Personal, Financial, Work, and Local. In the PERI survey-based life events data, participants self-reported the type of events, whereas the Facebook data was manually coded based on reading through the posts using the same PERI survey categories3.

Anticipation Anticipation is a characteristic of life events— anticipated events can be those that one can hope or worry about in the next six months105. Life events in both the survey and Facebook were labeled with anticipation labels3. Examples of anticipated events include buying a house and childbirth/pregnancy-related events, whereas unanticipated events include accidents or getting laid off at work.

Valence Valence is the positivity or negativity of a life event. In the PERI survey, participants self-reported valence of life events on a 7-point scale of “Extremely Negative” to “Extremely Positive.” The VADER106 tool was used to identify the major sentiment of a life event disclosure across negative, neutral, and positive, and assigned this label as the valence for life event entries3. For comparability across datasets, these labels were re-scaled on a scale of -1 (negative) to +1 (positive).

Intimacy Intimacy of a life event constitutes of how intimate or how comfortably an individual can open up about a life event to personal, close, trusted others, and public circles of relationships17. Life events were annotated with an intimacy label on a Likert scale of Low, Medium, and High.

Temporal status Life events can be grouped based on temporal status—either as continuous or discrete events. In the PERI life events survey, participants self-reported the temporal status, and the social media disclosures were manually labeled3.

Scope The scope of a life event consists of how much the event directly relates to an individual themselves, or their close ones, or more generic circles107. Scope of directness was labeled on a 3-point Likert scale where 1) Low scope events included generic events like bad weather, 2) Medium scope events associate with someone close and leave an indirect effect on the individual (e.g., spouse’s pregnancy, child going to school), and 3) High scope events are unique and direct on an individual (e.g., disease diagnosis)3.

Significance Each life event is associated with a degree of significance on an individual’s life108. In the PERI survey, participants self-reported significance (7-point scale of Lowest to Highest Significance). For Facebook disclosures, each event was labeled with a significance rating based on the PERI scale32. The significance ratings were separately standardized on a min-max scale of 0-1 to make the ratings comparable across the two datasets. We used this scaled score in our ensuing analyses.

Statistical power of the participant pool

Although we cannot claim absolute generalizability and representativeness of our participant pool, our dataset includes a demographically and psychologically diverse sample of participants from across the U.S. (Table 6). To assess whether our sample size was sufficient for the regression analyses conducted, we performed a power analysis, as per Dattalo (2008)109. Power analysis estimates the minimum number of participants needed to detect meaningful effects in a population, given the model complexity and expected effect sizes109,110. Assuming a small-to-moderate effect size (\(f^2\) = 0.15), an alpha level of 0.05, and 25 predictors (our regression model specification), the estimated required sample size is 172 participants. Our analytic sample of 236 exceeds this threshold, suggesting adequate statistical power to detect moderate effects in our regression models. While we acknowledge that detecting very small effects (\(f^2<\)0.05) would require larger samples, our longitudinal within-subjects design and repeated measures provide additional statistical sensitivity and support the robustness of our findings.

Operationalizing a causal-inference design

Obtaining Treated and Control datasets

Given the unavailability of “true counterfactual” data, we drew on synthetic control111 and placebo testing112 approaches to simulate our Control data. We drew on permutation test approaches from prior work113,109,115. Essentially, we permuted (randomized) several placebo dates (where there was no life event) within an individual’s Facebook timeline. These placebo dates are meant to rule out the likelihood that significant changes (if any) around life event occurrences could also happen around any other randomized (or placebo) dates. For each life event occurrence, we obtained 50 placebo dates which are outside of the range of two-week Before and After periods of the life event. Then, we repeated the same wellbeing effects measurements, i.e., the changes in the wellbeing outcomes in the two-week Before and After period around each placebo date. These placebo dates, along with their Before and After periods, served as the corresponding Control datasets for the actual life event occurrences from the Treated datasets.

Measuring the treatment effects

Next, we operationalized the effects of the treatment on wellbeing outcomes by adopting a difference-in-differences strategy34. First, for each wellbeing measure \(\texttt{W}\), we measured the differences in the After and Before wellbeing of the Treated instances (\(\Delta _{\texttt{T,W}}\)), and the same for the Control instances (\(\Delta _{\texttt{C,W}}\)). Then, we measured the \(\mathtt {DiD_W}\) as the difference in \(\Delta _{\texttt{T,W}}\) and \(\Delta _{\texttt{C,W}}\). We averaged the \(\mathtt {DiD_W}\)s across \(\texttt{N}\) instances as the average treatment effect (ATE). Equation 1 represents our operationalization approach. To measure statistical significance in wellbeing differences between the Treated and Control instances, we obtained the effect size (Cohen’s d) and paired t-tests. We also conducted the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS)-test to test against the null hypothesis that the Treated and Control wellbeing differences were drawn from the same distribution.

Checking for parallel trends assumption

To support the validity of our difference-in-differences (DiD) approach, we assessed the parallel trends assumption116. This assumption posits that, in the absence of the treatment (i.e., life event occurrence), the Treated and Control instances of wellbeing would have followed similar temporal trajectories. If this condition holds, any divergence in outcomes after the Treated can be more confidently attributed to the treatment effect rather than underlying group differences or time-varying confounders. To evaluate this, we visually inspected trends in wellbeing measures around the life event occurrence (day=0) in Fig. 1. The pre-treatment trajectories appear parallel for the Treated and Control datasets, suggesting that our approach led to comparable datasets. This supports the plausibility of the parallel trends assumption, and provides more support for the validity of our analyses.

Handling missing data

Life event disclosures in this study were entirely participant-driven; we only analyzed events that were voluntarily shared. There was no reliable way to infer non-disclosures. Prior work (e.g., Saha et al., 2021) has shown that individuals may choose to disclose life events in one modality (e.g., social media) but not another (e.g., self-report surveys), highlighting the challenges of identifying unreported events. For missing data in daily wellbeing surveys, when a participant failed to complete a survey on a given day, we imputed their individual mean wellbeing score based on their other completed responses as a baseline estimate. This approach allowed us to preserve these datapoints for analysis while minimizing assumptions about unobserved psychological states.

Conclusions

This study explored the impact of life event disclosures on mental wellbeing by examining the data from 236 participants who shared year-long Facebook activity and responded to periodic mental wellbeing surveys on positive and negative affect, stress, anxiety, and sleep quality, along with a life event survey. We adopted a quasi-experimental study design to find that sharing life events on social media enhanced wellbeing by increasing positive affect and sleep quality while reducing negative affect, stress, and anxiety. Notably, disclosing negative life events led to the most significant improvements in wellbeing, suggesting a protective effect of social media. Additionally, we examined engagement patterns of life event disclosures to find that life event disclosures elicit greater reactions and comments than other Facebook posts. Further, negative events are likely to receive more comments, but lower reactions than non-negative life event disclosures. These findings contribute to an empirical understanding of the complex relationship between online self-disclosure and (offline) mental wellbeing. This study offers both theoretical and practical implications for enhancing online experiences as well as supporting mental wellbeing in digital spaces.

Data availability

As per the consent process and IRB requirements, the raw data cannot be publicly shared. However, consented and de-identified data collected in the project can be made available upon request, subject to an appropriate data use agreement, if applicable. For additional details, the corresponding author, KS, can be contacted. More information on the Tesserae project’s data sharing are available at: tesserae.nd.edu/data-sharing/.

References

Harkness, K. L. & Monroe, S. M. The assessment and measurement of adult life stress: Basic premises, operational principles, and design requirements. J. Abnorm. Psychol. (2016).

Masuda, M. & Holmes, T. H. Life events: Perceptions and frequencies. Psychosom. Med. 40, 236–261 (1978).

Saha, K. et al. What life events are disclosed on social media, how, when, and by whom? In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–22 (2021).

Haimson, O. L., Brubaker, J. R., Dombrowski, L. & Hayes, G. R. Disclosure, stress, and support during gender transition on facebook. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 1176–1190 (2015).

Massimi, M. & Baecker, R. M. A death in the family: opportunities for designing technologies for the bereaved. In CHI (2010).

Brubaker, J. R., Hayes, G. R. & Dourish, P. Beyond the grave: Facebook as a site for the expansion of death and mourning. Inf. Soc. 29, 152–163 (2013).

De Choudhury, M., Counts, S., Horvitz, E. J. & Hoff, A. Characterizing and predicting postpartum depression from shared facebook data. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 626–638 (2014).

Burke, M. & Kraut, R. Using facebook after losing a job: Differential benefits of strong and weak ties. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 1419–1430 (2013).

Andalibi, N. & Forte, A. Announcing pregnancy loss on facebook: A decision-making framework for stigmatized disclosures on identified social network sites. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–14 (2018).

Haimson, O. L. et al. The major life events taxonomy: Social readjustment, social media information sharing, and online network separation during times of life transition. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. (2021).

Andalibi, N. Disclosure, privacy, and stigma on social media: Examining non-disclosure of distressing experiences. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 27, 1–43 (2020).

Cecchinato, M. E. et al. Designing for digital wellbeing: A research & practice agenda. In Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–8 (2019).

Barthorpe, A., Winstone, L., Mars, B. & Moran, P. Is social media screen time really associated with poor adolescent mental health? a time use diary study. J. Affect. Disord. 274, 864–870 (2020).

Hou, Y., Xiong, D., Jiang, T., Song, L. & Wang, Q. Social media addiction: Its impact, mediation, and intervention. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace13 (2019).

O’reilly, M. et al. Is social media bad for mental health and wellbeing? exploring the perspectives of adolescents. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 23, 601–613 (2018).

Coyne, S. M., Rogers, A. A., Zurcher, J. D., Stockdale, L. & Booth, M. Does time spent using social media impact mental health?: An eight year longitudinal study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 104, 106160 (2020).

Ernala, S. K., Rizvi, A. F., Birnbaum, M. L., Kane, J. M. & De Choudhury, M. Linguistic markers indicating therapeutic outcomes of social media disclosures of schizophrenia. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 1, 1–27 (2017).

Yuan, Y., Saha, K., Keller, B., Isometsä, E. T., & Aledavood, T. Mental health coping stories on social media: a causal-inference study of Papageno effect. In Proceedings of the ACM web conference 2023 (pp. 2677-2685), (2023).

Taylor, S. H., Hutson, J. A. & Alicea, T. R. Social consequences of grindr use: Extending the internet-enhanced self-disclosure hypothesis. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 6645–6657 (2017).

Teo, W. J. S. & Lee, C. S. Sharing brings happiness?: Effects of sharing in social media among adult users. In International Conference on Asian Digital Libraries, 351–365 (Springer, 2016).

De Choudhury, M. & De, S. Mental health discourse on reddit: Self-disclosure, social support, and anonymity. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, vol. 8, 71–80 (2014).

Bazarova, N. N. & Choi, Y. H. Self-disclosure in social media: Extending the functional approach to disclosure motivations and characteristics on social network sites. J. Commun. 64, 635–657 (2014).

Saha, K. & De Choudhury, M. Modeling stress with social media around incidents of gun violence on college campuses. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 1, 1–27 (2017).

Sharma, A., Choudhury, M., Althoff, T. & Sharma, A. Engagement patterns of peer-to-peer interactions on mental health platforms. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, vol. 14, 614–625 (2020).

Sharma, A., Lin, I. W., Miner, A. S., Atkins, D. C. & Althoff, T. Towards facilitating empathic conversations in online mental health support: A reinforcement learning approach. In Proceedings of the Web Conference vol. 2021, 194–205 (2021).

Ridout, B. & Campbell, A. The use of social networking sites in mental health interventions for young people: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 20, e12244 (2018).