Abstract

Daiobotanpito (DBT) is a Kampo formula traditionally used to treat abscesses in intestinal disorders. This double-blind, multicenter, randomized controlled trial was conducted at participating hospitals in Japan. Patients with CT-proven moderate acute diverticulitis received conventional therapy along with an oral DBT (treatment group) or placebo (control group) administered thrice a day for 10 days (Registration: jRCTs041180063). The primary outcome was the treatment success rate: fever reduction to < 37.5 °C within 3 days or/and elimination of abdominal pain within 4 days. Secondary endpoints included hospitalization days, changes in the inflammatory response, number of days before food intake, recurrence rate within 1-year, and adverse event rate. 171 participants were included in this study. No significant difference was observed in the treatment success rates between the DBT and placebo groups (P = .348). However, the DBT group showed a significant reduction in CRP levels on day 5 (P = .023), and patients with abscesses started oral intake significantly earlier than those in the placebo group (P = .046). In conclusion, the results of this study do not suggest that an add-on treatment with DBT in patients with moderate acute diverticulitis provides additional benefit., However, DBT may offer clinical benefits in cases involving abscesses or severe inflammation. Further prospective studies focusing on complicated diverticulitis are necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute diverticulitis occurs in approximately 4% of the patients with diverticulosis. Approximately 15% of these patients develop complications such as abscesses, perforation, fistulas, or colonic obstruction, while 15–30% experience recurrence1. According to the American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Update2 and Guidelines for Colonic Diverticulitis of the Japan Gastroenterological Association3, the initial treatment for uncomplicated colonic acute diverticulitis is bowel rest (i.e., fasting) and broad-spectrum antibiotics4. Despite abscess or perforation in colonic diverticulitis, conservative treatment is typically performed for limited peritonitis. Patients who do not respond to medical therapy should be considered for surgery depending on the clinical situation5. C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, white blood cell (WBC) count, clinical signs (generalized abdominal pain, constipation, vomiting), steroid use, number of episodes, and comorbidities are risk factors for complicated diverticulitis6.

Standard treatment has not changed noticeably recently. The applications of traditional Japanese medicine (Kampo) have gradually attracted worldwide attention. In Kampo, daiobotanpito (DBT; Da Huang Mu Dan-Tang in Chinese) is used for patients with excess Yang qi (qi means vital energy, and Yang qi mainly has a warming function) in the interior layers of the body, exhibiting signs of local qi, congestion, and blood stagnation. DBT comprises five crude drugs: Rhei Rhizoma, Natrium sulfuricum, Moutan Cortex, Persicae Semen, and Benincasae Semen. Notably, Rhei Radix et Rhizoma (rhubarb) and Moutan Cortex are responsible for draining heat and eliminating blood stasis. Persicae Semen promotes blood circulation and resolves blood stasis. Specifically, Benincasae Semen was described as promoting diuresis and detoxification, and Natrium sulfuricum as supporting the excretion of moisture and waste products. Kampo’s strategy is to discharge the toxin, eliminate phlegm (the viscous turbid pathological product that can accumulate in the body, causing various diseases), clear the heat, and open the restraint7.

In Japan, mainly extracts of Kampo prescriptions are administered. 148 types of medical-use Kampo extract preparations are covered by health insurance and are used with established safety. DBT is covered by health insurance for the treatment of constipation, and there have been no reports of serious side effects, so its safety has been established. In this study, pharmaceutical DBT extract approved by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in 1986 was used. This formulation is detailed in Table 1. Component names were cross-checked with STORKS (ver. 5.2, 17/11/2023, http://mpdb.nibiohn.go.jp/stork), a website contains quality and safety information of Kampo products authorized by Division of Pharmacognosy, Phytochemistry and Narcotics (DPPN), National Institute of Health Sciences (NIHS) of Japan and National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition (NIBIOHN).

Rhubarb in modern medical research in clinical and basic science settings has multiple advantages, including defervescence and anti-inflammatory actions, and the expulsion of various harmful materials (e.g., endogenous and exogenous toxins) from the bowel and body. Emodine in rhubarb protects against acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharides and improves respiratory function8. These effects may be related to reduced inflammation in patients with diverticulitis. Moutan Cortex, obtained from the root of Paeonia suffraticosa, is an herbal medicine widely used as an analgesic, antispasmodic, and anti-inflammatory agent. It inhibits the secretion of interleukin-8 and macrophage chemoattractant protein-1, potent mediators of acute neutrophil-mediated and chronic macrophage-mediated inflammation in human monocytic U937 cells, respectively9.

Moutan Cortex protects against sepsis induced by lipopolysaccharides or D-galactosamine10. It inhibits the lipopolysaccharide + interferon-γ-induced expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase, release of tumor necrosis factor-α, and activation of nuclear factor-κB11. Thus, each DBT crude drug has anti-inflammatory effects, and their combination may produce synergistic effects in disease treatment.

DBT has been used to treat intestinal abscesses in conditions such as diverticulitis or appendicitis12. DBT may be an alternative or supportive therapy for patients with acute diverticulitis, thus avoiding surgical treatment associated with prolonged recovery times and anesthesia-related risks, particularly in older adults. DBT has shown a notable positive effect treating acute diverticulitis. Compared with those in the group without DBT, patient outcomes in the group with DBT improved significantly regarding fever duration, abdominal pain, and administration of antibiotics13.

Therefore, we hypothesized that combining conventional treatment with oral DBT is superior to standard therapy for acute diverticulitis14 and designed an interventional method to study treatment outcomes in moderate-to-severe cases. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled trial to examine DBT’s effect on acute diverticulitis, as even Japanese guidelines have not yet described this approach3. The sample was larger than that in previous studies; furthermore, we analyzed moderate-to-severe cases, while previous studies only analyzed severe cases.

Methods

Study design

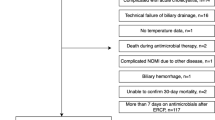

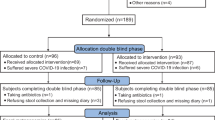

A consolidated standard of reporting trials (CONSORT) flow chart is shown in Fig. 1. This study was a two-group, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial that evaluated the efficacy and safety of DBT in patients with acute diverticulitis. We ensured adequate representation of male and female patients. The patients were recruited from the gastroenterology inpatient departments of 23 hospitals in Japan. Informed consent was obtained from all participants or their families. The study protocol was designed in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and regional regulations. Central ethical approval of this study has been confirmed from the Central Review Board of Kanazawa University Hospital (reference approval number 6058) and we will not begin recruiting at other centers in the trial until local ethical approval has been obtained. Patient enrollment was conducted from March 2018 to March 2022.This study was initially registered at UMIN (UMIN000027381) on 18/05/2017 and later at jRCT (jRCTs041180063) on 01/03/2019 following legal requirements in Japan. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Patient eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows.

-

1.

Moderate-to-severe diverticulitis: diagnosis based on computed tomography (CT) showing a diverticulum-like structure combined with tenderness or abdominal pain, thickening of the colon wall, signs of inflammation of pericolonic fat, tissue density, and vascular involvement. Pericolonic abscess, free air or extravasation, and fluid accumulation were assessed for prognosis purposes.

-

2.

Aged 20–75 years.

-

3.

Ability to communicate with investigators.

-

4.

Abdominal pain and/or fever > 37.5 °C.

-

5.

Provided written informed consent after receiving information and understanding the study and its objectives.

The exclusion criteria were as follows.

-

1.

Severe dysfunction in the following based on blood test results within 4 weeks of treatment onset:

-

a.

Renal function: Serum creatinine value 1.5-fold higher than the upper limit of the institutional standard.

-

b.

Liver function: serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) value 3-fold higher than the upper limit of the institutional standard.

-

c.

Central nervous function: encephalopathy or its suspicion.

-

d.

Electrolytes: serum sodium level < 125 mEq/L, serum potassium level < 3.3 mEq/L.

-

2.

Malnutrition: serum albumin level < 2.5 g/dL.

-

3.

Symptoms of obstructive ileus.

-

4.

Chronic anorexia, abdominal pain, and/or diarrhea before the onset of colorectal diverticulitis.

-

5.

Performance status: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score ≥ 3 before the onset of colorectal diverticulitis.

-

6.

History of DBT administration.

-

7.

Treatment with insulin preparations.

-

8.

Immunocompromised status.

-

9.

Pregnancy or postpartum status.

-

10.

Advanced allergy to Kampo formulas.

Randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding

Baseline measurements were performed before randomization. The web-based randomization system used in this trial was provided by an independent academic research organization at the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine. The principal investigators (PIs) or research coordinators accessed the web-based registration and randomization system URL, registered themselves, and obtained the allocation results. Registered case information obtained was entered into a case report form and faxed to the data center. The participants were allocated to each treatment group using the central registration system. Randomization was performed using the minimization method, in which history of diverticulitis (initial or recurrence) and severity (abscess formation on CT and/or CRP level ≥ 10 mg/dL, or no abscess formation and CRP level < 10 mg/dL) were used as adjustment factors. Enrolled patients who provided informed consent were randomized 1:1 into two groups: (1) experimental treatment group—10-day DBT regimen plus conventional therapy and (2) control group—10-day placebo regimen plus conventional therapy. Only the number of allocations was written in the test drug box, and nobody except the data center knew whether the drug was DBT or a placebo. All participants and treatment providers, those measuring the outcomes, and those who analyzed the data were blinded to the treatment allocation.

Interventions

The DBT extract composition is described in the Introduction. In this study, pharmaceutical extract of DBT which approved by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in 1986 was used. 7.5 g of DBT extract granules (Tsumura, Tokyo, https://medical.tsumura.co.jp/products/033/pdf/033-tenbun-e.pdf) contains 3.5 g of a dried extract of the mixed crude drugs. DBT formula is detailed in Table 1. A placebo was also manufactured by Tsumura Co., Ltd., based on good Manufacturing practice standards. The placebo shape and taste were almost identical to real DBT. The DBT or placebo extract (2.5 g) was administered thrice a day for 10 days. The treatment was initiated after obtaining informed consent and web-based randomization. No restrictions were imposed on the standard treatments for acute diverticulitis or any other disease while DBT was administered. When clinical evolution was appropriate, a regular diet was initiated, the patient was discharged, and the patient returned as an outpatient 1 week later. We asked patients whether they had a relapse 1 year after discharge.

Primary endpoint

Treatment success rate.

If the following criteria were satisfied, the treatment was defined as successful.

-

1.

Fever relief < 37.5 °C within 3 days and abdominal pain relief within 4 days of treatment at baseline.

-

2.

Abdominal pain relief within 4 days of treatment at baseline in patients without fever.

Symptom change was defined as:

-

1.

Fever relief

Absence of fever ≥37.5°C without antipyretic analgesics use, or absence of fever 6 h post-administration of antipyretics.

-

2.

Abdominal pain elimination

Absence of abdominal pain without antipyretic analgesics use or absence of pain 6 h after administering the analgesic. The VAS score was obtained thrice daily during the abdominal pain.

Secondary endpoints

-

1.

Number of hospital days: Number of days from registration until discharge, including the day of registration.

-

2.

Change in inflammatory response (CRP level, WBC count, and neutrophil count): Values differences at the time of registration (baseline values) for each measurement on each measurement day.

-

3.

Thermal type: Body temperature values differences at the time of registration (baseline values) and on each measurement day.

-

4.

Number of days until oral ingestion: Number of days from trial registration until the beginning of oral intake, including the registration date.

-

5.

Recurrence rate (1-year follow-up): recurrence rate 1 year after randomization. On discharge, the patients with symptoms recurrence were diagnosed with colonic diverticulitis.

-

6.

Adverse events (types and frequency of side effects): Side effects were recorded for each observed adverse event, and the type and frequency were determined.

Statistical considieration

The sample size was calculated based on the treatment success rate, estimated from our retrospective study’s results (75% for patients treated with DBT and 50% for those without DBT13). In the previous study, the dropout rate was 2%; therefore, we assumed a 2% dropout rate. A sample size of 170 patients (85 per arm) was required to provide the trial with 90% power to detect the superiority of the experimental treatment over the control treatment at a two-sided alpha level of 5%.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 28). Numerical demographic variables (such as age, weight, and height) in each group were compared using the two-sample independent t-test, and categorical variables (such as sex, history of diverticulitis, and presence or absence of abscesses) were compared using the chi-square test. The chi-square test was also used to compare the number of patients with improved abdominal pain, fever, and blood test results (WBC count, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, and CRP level) in each group. The level of significance was set at P <.05. An ad hoc analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of DBT on inflammation and severity.

Quality control and trial management

The management structure comprised the PI, trial management group, and data monitoring committee. The trial management group was responsible for conducting the trial and met monthly to discuss progress. The PI visited each collaborating hospital for face-to-face meetings and shared information to promote patient recruitment. The data monitoring committee periodically reviewed interim safety data and study operations. All data were monitored monthly using a central monitoring method. The final analysis was performed by the data center and our statistician. Before patient recruitment, the data monitoring committee met once. Data quality was checked regularly by research assistants and overseen by monitors. All modifications were marked on case report forms, and data managers rechecked the data before they were officially logged. The database was locked after all data had been cleaned.

Results

Patient characteristics

Among the 173 patients who met the selection criteria, 171 participated in the study (Mean age: 49.7, 86 in the DBT group and 85 in the placebo group)(Fig. 1). Participants’ demographic variables, including the administered antibiotics, are shown in Table 2. The body mass index (BMI) was significantly higher in the placebo group than in the DBT group (P =.046). No other parameters, including sex and gender, showed differences between the two groups.

Efficacy

Among 171 patients, four who failed to initiate protocol treatment and eight who failed to continue were excluded, leaving 77 patients in the DBT group and 82 in the placebo group in initial analysis. Furthermore, seven patients could not be contacted for the evaluation of the recurrence rate after 1 year; therefore, the final analysis included 72 patients in the DBT group and 80 patients in the placebo group.

The primary and secondary endpoint results, including those of the sensitivity analyses, are shown in Table 3. The number of patients with improvements in the main endpoints (abdominal pain and fever) was similar in both groups (X2 [1, N = 159] = 0.880; P =.348). Comparisons of the secondary endpoints are presented in Table 3, and findings for both groups were similar. A chi-square test of independence was performed to determine the number of relapses, which was similar in both groups (X2 [1, N = 152] = 0.934; P =.334; Table 3).

The treatment success (P =.498) and recurrence (P =.350) rates did not differ between male and female patients.

A chi-square test of independence was performed to determine the number of patients with an increase of > 16 000/µL in the lymphocyte count on the fifth day of treatment (Table 4), and it was significantly more in placebo group than in DBT group (X2 [1, N = 128] = 4.556; P =.033). The same test was performed to determine the number of people with a decrease of > 11 mg/dL in CRP levels on the fifth day of treatment, and it was significantly more in DBT group than in placebo group (X2 [1, N = 140] = 5.190; P =.023) (Table 4). There was no difference in the recurrence rate.

For the ad hoc analysis, a comparison of patients with abscesses is shown in Table 5. The improvement rate was slightly higher in the DBT group than in the placebo group. Oral administration was initiated significantly earlier in the DBT group than in the placebo group.

Adverse events

Adverse events were reported in 11 of the 170 patients (DBT group, 5 [6.4%]; placebo group, 6 [7.3%]). Gastrointestinal symptoms included diarrhea in two patients, which was suspected to be DBT-related. Other symptoms, including headache and neutropenia, were judged to be unrelated to drug administration. One placebo-treated patient underwent sigmoid colon resection due to perforation of the colon, but the causal relationship with the study was unclear.

Discussion

The treatment success rates between the DBT and placebo groups were similar, with no significant differences in the number of patients who experienced relapse. This indicates that DBT administration did not improve the treatment success rate for acute diverticulitis of the colon, despite previous studies12,13 suggesting that DBT can be effective for early recovery and prevention of diverticulitis recurrence. However, it is important to note that the earlier study mainly included severe cases, where surgical intervention was considered, while most patients in the current study had moderate cases of acute diverticulitis. This difference in patient populations may explain the lack of significant findings in the primary outcome of treatment success.

In this study, only 13 of 171 patients (DBT group: 7; placebo group: 6) had abscess formation, and only 55 of 170 had CRP levels > 10 mg/dL, suggesting that the majority of the cases were moderate. In the subset of patients with abscess formation, successful treatment was achieved in 2/7 (33%) cases in the DBT group and 4/6 (57.1%) in the placebo group. One placebo-treated patient underwent sigmoid colon resection due to perforation, while no patients in the DBT group required surgery. Despite the small number of cases, which limits the robustness of these findings, the DBT group started food intake significantly earlier than the placebo group (P =.046), suggesting a potential benefit in terms of early recovery. In moderate cases, antimicrobial administration for 3 days is typically sufficient to reduce inflammation4. Traditional medicine suggests that DBT is effective against intestinal carbuncles7, which may be analogous to abscess formation, indicating that DBT might be more suitable for severe cases.

As for classification of acute diverticulitis, the modified Hinchey classification is widely used in clinical practice to distinguish the stages of diverticulitis complicated by abscess or peritonitis15. Currently, the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) proposed classification that focus on patients’ computed tomography (CT) images15,17. Although these classification was not used when we planned this study, 156 patients are in class II (colon micro-perforation or pericolic phlegmon without abscess), while 15 patients in class III (Localized pericolic abscess) in AAST classification retrospectively. It would be better to include patients in class III or IV (Distant or/and multiple abscess) in future study.

The patients with an increase of > 16 000/µL in the lymphocyte count on the fifth day of treatment was more in the placebo group than in DBT group, and the patients with a decrease > 11 mg/dL in CRP levels on the fifth day of treatment were more in DBT group than in placebo group. These findings indicate that the DBT group showed more rapid improvement than the placebo group, suggesting that severe inflammation at the time of enrollment was related to more effective treatment. Future prospective studies should focus specifically on patients with complicated diverticulitis, such as those with abscess formation or classified as AAST grade III or higher.

Diverticulae occur primarily in the sigmoid colon in Western countries2, whereas the right side or bilateral colon is more commonly involved in Japan3. In this study, more patients had right-sided diverticulitis (Table 2), consistent with a previous Japanese study3.

Various antibiotics were used for patients in this study, based on each center’s clinical practice antibiotics use. There is no standardized medical treatment for uncomplicated acute diverticulitis17. In this study, we did not limit the types of antibiotics used (all antibiotics are noted in Table 2). Cefmetazole was the most commonly administered drug in this study. Most herbal medicines are orally administered, and many components come into contact with the intestinal microflora in the gastrointestinal tract, which modifies some before being absorbed into the bloodstream18. Although intravenous antibiotics administration may influence the intestinal microflora and DBT’s effect might be altered, unlike with classical therapy, our study indicated that intravenous antibiotics and DBT could be used safely simultaneously.

We considered the correlation between diverticulitis incidence and BMI, sex, age, and season and the correlation between the success rate of diverticulitis treatment and antibiotics, BMI, sex, age, and season.

In conclusion, the results of this study do not suggest that an add-on treatment with DBT in patients with moderate acute diverticulitis provides additional benefit.However, DBT may offer clinical benefits in cases involving abscesses or severe inflammation. Further prospective studies focusing on complicated diverticulitis are necessary to clarify DBT’s role in such cases.

CONSORT flowchart. Among the 173 patients who met the selection criteria, 171 participated in the study (86 in the DBT group and 85 in the placebo group). Among those patients, four who failed to initiate protocol treatment and eight who failed to continue were excluded, leaving 77 patients in the DBT group and 82 in the placebo group. Furthermore, seven patients could not be contacted for the evaluation of the recurrence rate after 1 year; therefore, the final analysis included 72 patients in the DBT group and 80 patients in the placebo group. DBT: daiobotanpito.

Data availability

The data will not be available for public access because of patient privacy concerns, but will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DBT:

-

Daiobotanpito

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- PIs:

-

Principal investigators

References

Stollman, N., Smalley, W., Hirano, I. & AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American gastroenterological association Institute guideline on the management of acute diverticulitis. Gastroenterology 149, 1944–1949 (2015).

Peery, A. F., Shaukat, A. & Strate, L. L. AGA clinical practice update on medical management of colonic diverticulitis: expert review. Gastroenterology 160, 906–911 (2021). e1.

Nagata, N. et al. Guidelines for colonic diverticular bleeding and colonic diverticulitis: Japan gastroenterological association. Digestion 99 (Suppl 1), 1–26 (2019).

Soma, K. et al. Efficacy and safety of a strategy for reviewing intravenous antibiotics for hospitalized Japanese patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis: a single-center observational study. Intern. Med. 61, 3475–3482 (2022).

Fowler, H. et al. Failure of nonoperative management in patients with acute diverticulitis complicated by abscess: a systematic review. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 36, 1367–1383 (2021).

Bolkenstein, H. E. et al. Risk factors for complicated diverticulitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 32, 1375–1383 (2017).

Scheid, V. et al. Chinese Herbal Medicine: Formulas and Strategies 2nd edn 685–772 (Eastland, 2009).

Xiao, M. et al. Emodin ameliorates LPS-induced acute lung injury, involving the inactivation of NF-κB in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 19355–19368 (2014).

Fu, P. K. et al. Moutan cortex radicis improves lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in rats through anti-inflammation. Phytomedicine 19, 1206–1215 (2012).

Oh, G. S. et al. Inhibitory effects of the root cortex of Paeonia suffruticosa on interleukin-8 and macrophage chemoattractant protein-1 secretions in U937 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 84, 85–89 (2003).

Chung, H. S. et al. Inhibition of nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha by Moutan cortex in activated mouse peritoneal macrophages. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 30, 912–916 (2007).

Utsunomiya, T. et al. Acute appendicitis with fecaliths requiring surgery in a patient with COVID-19 successfully treated with Daiobotanpito and antibiotics. Trad Kampo Med. 10, 72–74 (2023).

Ogawa, K. et al. Effectiveness of traditional Japanese herbal (kampo) medicine, daiobotanpito, in combination with antibiotic therapy in the treatment of acute diverticulitis: a preliminary study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. ; 2013:305414. (2013).

Ogawa-Ochiai, K. et al. Study protocol for Daiobotanpito combined with antibiotic therapy for treatment of acute diverticulitis: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 21, 531 (2020).

Sartelli, M. et al. A proposal for a CT driven classification of left colon acute diverticulitis. World J. Emerg. Surg. 10, 3 (2015).

Camilla, C. et al. What are the differences between the three most used classifications for acute colonic diverticulitis? A comparative multicenter study. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 96, 326–331 (2024).

Schechter, S., Mulvey, J. & Eisenstat, T. E. Management of uncomplicated acute diverticulitis: results of a survey. Dis. Colon Rectum. 42, 470–476 (1999).

Kim, D. H. et al. Metabolism of Kalopanaxsaponin B and H by human intestinal bacteria and antidiabetic activity of their metabolites. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 21, 360–365 (1998).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Asuka Mizushima who collected data and cared for study institutes, Ms. Ayako Kimura who provided and cared for study patients, and Prof. Toshinori Murayama who served as scientific advisors and critically reviewed the study proposal.

Funding

This study was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (17lk0310031h0001) and the Fund of Kanazawa University for Clinical Studies. The funders played no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KO, KY, SS and HI designed the study protocol and drafted the manuscript. KO conceptualized the study, wrote original draft preparation, administered project, and acquired funding. ST, AM, HI, KK, TD, EO, GN, TH, MS, TK, KI, OO, MH, HH, TK, TT, TY, IY, MS, AT, YM, ME, YM, KN, SK, TH, HD, KU, and YK recruited participants and drafted the manuscript. KM and HL were responsible for the statistical analysis. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

KO (Keiko Ogawa-Ochiai) reports grants from Tsumura Co., Ltd. outside the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ogawa-Ochiai, K., Tsuji, S., Maeda, A. et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the Kampo formula daiobotanpito combined with antibiotic therapy for acute diverticulitis. Sci Rep 15, 21069 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07385-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07385-9