Abstract

The current study aimed to provide further evidence of the structural validity of the 16-item-short version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS), a widely-used tool for assessing an individual’s emotional state. This is significant for various research inquiries in clinical and social psychology. In order to cross-validate previous findings, an additional evaluation of the factorial structure and the psychometric properties is necessary in a newly collected dataset. A representative sample for age and gender of N = 2503 with 1329 (53%) female, 1173 (47%) male, and 1 (< 1%) diverse, with a mean age of M = 46 (SD = 18) was collected. The model fit for the four-factor model was acceptable, with good reliability for all factors. We found evidence for (partial) strict invariance between gender and age groups. There were small to moderate group differences for the Anger and Vigor subscales regarding age. We report normative percentile ranks. Our findings suggest that the POMS-16 is a dependable and structurally valid gauge of mood states. Especially in situations where a brief and cost-effective assessment is preferred, the POMS-16 should be a considered option.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Profile of Mood States questionnaire (POMS) is a widely used questionnaire to assesses the mental state of various medical patients, including those with heart surgery, cataracts, epilepsy, and sleep apnea syndrome1,2,3,4. POMS has also been used in (psycho)oncology to evaluate various outcomes, such as quality of life, stress levels or the impact of interventions5. More frequently, POMS measures psychological and pharmacological quantities in clinical, as well as in occupational and sports medicine studies6,7,8.

The original American version of POMS9,10 consists of six mood dimensions, assessed with 65 items rated on a 5-point scale. The mood dimensions Anger-Hostility, Confusion-Bewilderment, Depression, Fatigue-Inertia, and Tension-Anxiety are summed up and Vigor-Activity is subtracted from the sum to obtain the Total Mood Disturbance Scale. Internal consistency coefficients range from 0.90 to 0.94, and retest reliabilities range from 0.65 to 0.74 in clinical samples10. Similar values were reported non-clinical samples, with higher retest reliabilities over a one-week interval11.

In other versions POMS utilizes two main prompts on a 7-step answer scale: 'How have you felt during the past week including today?' and 'How do you feel right now?' The ‘past week’ framing is usually preferred to the ‘right now’ framing as it measures reoccurring states and at the same time retains sensitivity to interventions. And although McNair et al.10 replicated the original structure using the ‘right now’ framing, it should be evident that perceptions of intensity, seriousness, and frequency of episodes may vary with the reference period. In Anglo-Saxon contexts, scores from the ‘past week’ instruction were higher than those from multiple ‘right now’ assessments. Terry et al.12 recommended using the ‘right now’ prompt due to recall being influenced by mood and significant events.

Although the internal structure of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) is well-validated, the Confusion factor is regarded as a cognitive state. Some adaptations have retained the Friendliness component due to the restricted scope of pleasant mood states encompassed13,14.

Other factors that can affect mood state responses, such as diverse mood state descriptors, response formats, and assessment circumstances have been discussed in previous research. Especially, the circumstances of mood state assessment, including the timing and location, are crucial measurement elements12,15,16. Overall, instruction type and test administration conditions both play important roles and the invariance of mood scores needs to be ascertained in the interpretation of mood states12,16,17.

The 35-item version of the POMS (German version by Biehl et al.18) generally appears to be the most widely used and it consists of the four scales: dejection/anxiety, fatigue, vigor, and anger, evaluated using a 5- or 7-point response scale. Satisfactory psychometric properties were reported for this version based on a student sample. However, when applied to a general population sample, only a limited satisfactory factorial structure was observed19. Therefore, Petrowski et al.20 conducted an item selection for a robust factorial structure. Using exploratory factor analysis and model comparisons of potential item subsets21, a four dimensions scale with total of 16-item set was identified, ensuring good reliability and factorial structure. Confirmatory factor analysis showed a good fit and high reliability for the subscales (0.86 to 0.91). This 16-item short version is strictly invariant across age groups, with strong and partial strict invariance by sex.

This 16-item short version was developed from an older dataset of the long version. To ensure its validity and independence from the excluded 19 items of the POMS-35, further evaluation of the factorial structure and psychometric properties is necessary using a newly collected dataset exclusively implementing the 16-item version. Thus, the current study aims to evaluate the factorial structure and psychometric properties of the 16-item short version with up-to-date norm values from a representative sample of the German general population.

Method

The present investigation was part of a representative survey of the German general population. An independent institute for opinion and social research (USUMA, Berlin, Germany) organized and carried out the data collection. Participants were required to be at least 14 years of age and sufficient German-speaking capabilities. In addition to providing socio-demographic information, participants completed several self-report questionnaires on physical and psychological symptoms. The study participants were selected by means of a random-route sampling method with 258 sample points. Initially, 5418 households were selected, and 5389 were deemed eligible for participation. The Kish selection grid22 was then utilized to select individuals within households. In total, 2503 individuals took part in the survey (46% of those contacted). The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Leipzig (043/20-ek) and adhered to ICH-GCP guidelines, the ICC/ESOMAR International Code of Marketing and Social Research Practice, and the Declaration of Helsinki. After being educated about the study procedures, data collection, and anonymization of personal data, all participants gave verbal informed consent, in accordance with German law.

Instruments

In the present study the short version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS23) by Petrowski et al.20 was implemented. The short version consists of 16 items spread across 4 scales: dejection / anxiety (4 items), fatigue (4 items), vigor (4 items) and anger (4 items). Similar to the different English versions the 16 items were answered on a 7-point Likert scale and evaluated for "the last 24 h".

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed in R using the packages dynamic, lavaan, and semTools24,25,26. The analysis script is published at https://github.com/bschmalbach/POMS_Validation/blob/main/POMS16.Rmd. For the confirmatory factor analysis, we utilized robust full-information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML). We made this decision because there were a sizable number of respondents with missing values (mostly singular values): 143 (5.7%) individuals had at least one missing value. Thus, by using FIML, we were able to use all available information and not selectively include responses based on missingness. Furthermore, the items exhibited only a slightly positive skewness of 0.62, and thus robust maximum likelihood estimation appears acceptable. To assess the model fit, we considered the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR). We employed cutoffs of 0.95 for CFI and TLI, and 0.08 for RMSEA and SRMR27,28. To supplement, this analysis we also considered the dynamic cutoff values as proposed by McNeish and Wolf29. To evaluate scale reliability, we examined McDonald’s ω30.

To analyze differences between sociodemographic groups, we first tested for measurement invariance by comparing increasingly restrictive models: configural invariance (baseline model), metric invariance (equal loadings across groups), scalar invariance (equal loadings and indicator intercepts across groups), and strict invariance (equal loadings, indicator intercepts, and indicator residuals across groups). The fit should not decrease by more than 0.01 in terms of CFI and RMSEA between models31,32. To supplement these analyses, we report RMSEAD according to Savalei and colleagues33. Its interpretation is equivalent to the standard RMSEA index with the customary 0.08 cutoff. For the ANOVA comparisons and normative data, only respondents with complete data on a given subscale were included in the analysis. We conducted ANOVAs to check whether there are meaningful differences in POMS scores between sociodemographic groups. This served the primary purpose of determining the necessity of dedicated norm values for each subgroup. In addition to conducting the ANOVAs, we checked for variance homogeneity and normality of residuals—both assumptions were fulfilled or only violated mildly. The normative values were then computed based on percentile ranks for each given sum score.

Results

Sample

The initial study sample consisted of 2503 responsdents. Of those, 1329 (53%) were female, 1173 (47%) were male, and 1 was diverse (< 1%). The mean age was 46 (SD = 18), which we split into three even age groups: ≤ 36 years (n = 824, 33%), 37–55 years (n = 808, 32%), and > 55 years (n = 871, 35%). A more detailed description is reported in Table 1.

CFA

The 4-factor model established by Petrowski et al. (2021) exhibited acceptable fit in this sample when compared to the customary fixed cutoffs, χ2(98) = 819.66, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.957, TLI = 0.947, RMSEA = 0.056, SRMR = 0.040. Only the TLI slightly falls below the threshold of acceptability. The dynamic cutoffs largely replicate these findings: Level 1 misspecified models would yield SRMR = 0.070, RMSEA = 0.047, and CFI = 0.977, Level 2 models would yield SRMR = 0.077, RMSEA = 0.068, and CFI = 0.959, and Level 3 misspecification would yield SRMR = 0.084, RMSEA = 0.088, and CFI = 0.940. This puts our empirically determined fit values pretty convincingly into Level 2 (with SRMR being better than expected). This corresponds to “fair” fit according to McNeish and Wolf. Reliability (ω) of the factors was good, ranging between 0.859 and 889.

Additionally, we analyzed a unifactorial model—since the POMS is often summarized using a Total Mood Disturbance Score. Our findings show that such a model is completely unacceptable, χ2(104) = 6339.45, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.621, TLI = 0.563, RMSEA = 0.155, SRMR = 0.126, ω = 0.716.

Measurement invariance

Table 2 shows the results of the measurement invariance tests. For gender, there were no meaningful differences in the measurement model at any level. That is, strict invariance can be assumed. In contrast, age groups exhibited some differences with regard to the residuals. Thus, we can only assume partial strict invariance. Specifically, we freed the residuals of the two items with the largest deviations between the age groups: “full of pep” and “vigorous”. This indicates that while the vigor factor may be comparable across ages (given metric and scalar invariance), the error terms aren’t—which is an indication for differing reliability between groups.

Group differences and norm values

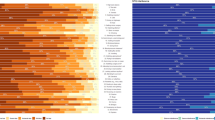

As can be seen in Table 3, there were small-to-moderate differences between age groups with regard to the Anger and Vigor subscales. Specifically, younger respondents reported higher values in both subscales. Some significant yet smaller (R2 < 0.01) differences were observable for other comparisons as well. Even though these differences are relatively small, they demonstrate the need for dedicated normative values for each subgroup. Tables 4, 5, 6, 7 display normative values for the German general population.

Discussion

The "Profile of Mood States" (POMS10) is a widely used questionnaire in clinical research. For epidemiological studies, short instruments with strong psychometric properties are essential. Therefore, a short screening version was derived from the long form. To cross-validate those results in a sample featuring only the final 16 items, a representative sample of the general population in Germany was collected. The study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties, factorial structure, and norm values of the 16-item short version of the POMS.

Based on the newly collected representative dataset, the model fit for the four-factor model was acceptable, with good reliability for all factors. We found evidence for (partial) strict invariance across gender and age groups. Small to moderate differences were observed for the Anger and Vigor subscales regarding age. Further, results from the unifactorial CFA discourage from the usage of the Total Mood Disturbance Score. The English version of the POMS by Cella et al.34 consists also of a small number of items (11 items) but only provides a Total Mood Disturbance score without subscales. Therefore, the 16-item version provided here is the shortest available version of the POMS that maintains subscale measurements. Furthermore, it previously showed a high correlation with the long 35-item version20.

While the large sample size and broad age range are strengths of this study, the representativeness for the general population may limit applicability to samples with altered moods, such as clinical settings. To further validate or refute the factorial structure, the POMS should be applied to diverse groups, including clinical samples. In addition, further consideration should be given to the process of external validation, specifically the usage of concrete criteria (such as behaviors) which the POMS could predict.

In sum, this investigation presents evidence of the POMS-16’s structural validity and reliability. It can be recommended for social, personality, and clinical research interested in changes in affect and mood.

Data availability

Datasets are available upon reasonable request from Katja Petrowski at kpetrows@uni-mainz.de.

References

Elliott, P. C. et al. Changes in mood states after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 9(3), 188–194 (2010).

Pesudovs, K., Weisinger, H. S. & Coster, D. J. Cataract surgery and changes in quality of life measures. Clin. Exp. Optom. 86(1), 34–41 (2003).

Pulliainen, V., Kuikka, P. & Kalska, H. Are negative mood states associated with cognitive function in newly diagnosed patients with epilepsy?. Epilepsia 41(4), 421–425 (2000).

Lee, I. S., Bardwell, W., Ancoli-Israel, S., Loredo, J. S. & Dimsdale, J. E. Effect of three weeks of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on mood in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Sleep Med. 13(2), 161–166 (2012).

Baker, F., Denniston, M., Zabora, J., Polland, A. & Dudley, W. N. A POMS short form for cancer patients: psychometric and structural evaluation. Psycho-Oncology J. Psychol. Soc. Behav. Dimens. Cancer 11(4), 273–281 (2002).

Fletcher, M. A., Lopez, C., Antoni, M., Penedo, F., Weiss, D., Cruess, S. & Klimas, N. G. A pilot study of cognitive behavioral stress management effects on stress, quality of life, and symptoms in persons with chronic fatigue syndrome (2011).

Lochbaum, M., Zanatta, T., Kirschling, D. & May, E. The Profile of Moods States and athletic performance: A meta-analysis of published studies. European journal of investigation in health, psychology and education, 11(1) (2021).

de Lira, C. A. B. et al. Identifying mood disorders and health-related quality of life of individuals submitted to mandatory military service. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 33(1), 9–14 (2021).

McNair, D. M., Lorr, M. & Droppleman, L. F. Manual for the profile of mood states (POMS). San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service (1971).

McNair, D., Lorr, M. & Droppleman, L. Profile of mood states manual (rev.). San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service (1992).

Gibson, S. J. The measurement of mood states in older adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 52(4), 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/52B.4.P167 (1997).

Terry, P. C., Stevens, M. J. & Lane, A. M. Influence of response time frame on mood assessment. Anxiety Stress Coping 18(3), 279–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800500134688 (2005).

Morfeld, M., Petersen, C., Krüger-Bödeker, A., Von Mackensen, S. & Bullinger, M. The assessment of mood at workplace-psychometric analyses of the revised Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire. GMS Psycho-Soc. Med. 4 (2007).

Netz, Y., Zeav, A., Arnon, M. & Daniel, S. Translating a single-word items scale with multiple subcomponents–A Hebrew translation of the profile of mood. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 42(4), 263–270 (2005).

Watson, D., Clark, L. A. & Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 (1988).

Terry, P. C. & Lane, A. M. Normative values for the profile of mood states for use with athletic samples. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 12(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200008404215 (2000).

Andrade, E. & Rodriguez, D. Factor structure of mood over time frames and circumstances of measurement: Two studies on the Profile of Mood States questionnaire. PLoS ONE 13(10), e0205892. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205892 (2018).

Biehl, B., Dangel, S. & Reiser, A. Profile of mood states. Internationale Skalen für Psychiatrie (Weinheim, 1986).

Albani, C. et al. The German short version of “Profile of Mood States” (POMS): Psychometric evaluation in a representative sample. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 55(7), 324–330. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-834727 (2005).

Petrowski, K., Albani, C., Zenger, M., Brähler, E. & Schmalbach, B. Revised short screening version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) from the German general population. Front. Psychol. 12, 631668. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631668(IF:2.99) (2021).

Schultze, M. stuart: Subtests Using Algorithmic Rummaging Techniques. R package version 0.10.2 (2023). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=stuart.

Kish, L. A procedure for objective respondent selection within the household. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 44(247), 380–387 (1949).

McNair, D., Lorr, M. & Droppleman, L. F. Profile of mood states: Bipolar form. Educational and Industrial Testing Service: San Diego, CA (1988).

Wolf, M. G. & McNeish, D. Dynamic: An R package for deriving dynamic fit index cutoffs for factor analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 58(1), 189–194 (2023).

Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48(2), 1–36 (2012). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Jorgensen, T. D., Pornprasertmanit, S., Schoemann, A. M. & Rosseel, Y. semTools: Useful tools for structural equation modeling (2022). R package version 0.5–6. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semTools

Hu, L. T. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 (1999).

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H. & Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 8(2), 23–74 (2003).

McNeish, D. & Wolf, M. G. Direct discrepancy dynamic fit index cutoffs for arbitrary covariance structure models. Struct. Equ. Model. 31(5), 835–862 (2024).

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T. & Brunsden, V. From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br. J. Psychol. 105(3), 399–412 (2014).

Chen, F. F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834 (2007).

Cheung, G. W. & Rensvold, R. B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5 (2002).

Savalei, V., Brace, J. C. & Fouladi, R. T. We need to change how we compute RMSEA for nested model comparisons in structural equation modeling. Psychol. Methods (2023).

Cella, D. F. et al. A brief POMS measure of distress for cancer patients. J. Chronic Dis. 40(10), 939–942. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90143-3 (1987).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EB and KP conceptualized the study. EB supervised the data collection. BS and MZ analyzed the data. KP, BS and MB wrote the manuscript. All authors listed have made substantial, direct and intellectual contributions to the work, and approved it for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was reviewed and approved by University of Leipzig Medical Faculty Ethics Committee Käthe-Kollwitz-Str. 82 04109 Leipzig: 043/20-ek.

Consent to participate

All survey participants gave their informed consent in accordance to do so.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Petrowski, K., Bjelopavlovic, M., Zenger, M. et al. Psychometric properties and norm values of a short screening version of the profile of mood states POMS from the German general population. Sci Rep 15, 23889 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07388-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07388-6