Abstract

Leukodystrophies are a number of rare genetic disorders that influence the white matter of the brain. The current study aimed to identify the underlying genetic cause of leukodystrophy in 14 Iranian cases, mainly presented by hypomyelinating leukodystrophies. Whole exome sequencing was used for this purpose. Notably, a certain RARS1 variant (c.2T > C) was found in six cases. In addition, six cases carried homozygote variants in the GJC2, PLEKHG2, RNF220, POLR1C, DEGS1 and ACER3 genes, respectively. Finally, two patients carried a heterozygote variant in TMEM63A or TUBB4A, respectively. Taken together, the current study shows high prevalence of a certain RARS1 variant among Iranian patients with leukodystrophy. Moreover, a list of other genes was suggested as underlying causes of leukodystrophy in this population. Further studies are needed to elaborate the spectrum of genetic mutations in Iranian cases with leukodystrophy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leukodystrophies are a number of rare genetic disorders that influence the white matter of the brain. Hypomyelinating leukodystrophies include a subgroup of these disorders characterized by a remarkable and persistent defect in the myelin deposition within the central nervous system (CNS)1. MRI pattern recognition analysis2, genetic linkage and next generation sequencing methods3,4 have resulted in the identification of the etiology of these disorders in a number of patients. Since many of the identified genetic variants are individually rare, the resultant phenotypes have not been fully defined.

According to the first report of the Iranian Leukodystrophy Registry database (2016–2019), this condition is highly heterogeneous in terms of genetic background5. ARSA, HEXA, ASPA, MLC1, GALC, GJC2, ABCD1, L2HGDH, and GCDH have been the most frequently mutated genes in this cohort5.

The current study aimed to identify the underlying genetic cause of leukodystrophy in 14 Iranian cases, mainly presented by hypomyelinating leukodystrophies.

Cases

The current study was carried on 14 Iranian cases of leukodystrophy, including 10 females and 4 males (Table 1). Cases were referred to the Comprehensive Genomic Center, Tehran, Iran during 2018–2024 for molecular tests and counseling. Informed consent forms were signed by all parents. All patients were born to consanguineous parents. Patients’ age ranged from 4 months to 17 years. Generally, all cases had variable degrees of developmental delay affecting both cognitive and motor domains. Seizure was reported in three cases (cases 3, 4 and 8). Nystagmus was detected in two cases (cases 5 and 7).

Molecular diagnosis

First, DNA was retrieved from peripheral blood of the patients using the standard method. Whole exome sequencing (WES) was carried out using Illumina Novaseq6000 (Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea) with an average 100x coverage depth for > 98% of the targets. At that point, 100 paired-end base-pair reads were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh37/hg19). Analytical sensitivity of the test was set at 97% for single nucleotide variants and small insertions/deletions.

Variant prioritization strategy included several steps. The initial step was variant filtering based on quality metrics, including read depth, genotype quality, and allele frequency in public databases such as gnomAD. Then, we focused on variants with MAF < 1% and those predicted to be deleterious by in silico tools (e.g., SIFT, PolyPhen-2, and Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD)). All variants were assessed based on the public databases (including HGMD, ClinVar, LSDBs, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project, 1000 Genomes, and dbSNP), published articles, clinical data, segregation analyses, functional assays, and the expected functional or splicing impact based on evolutionary conservation analyses and in silico tools (PolyPhen-2 and SIFT).

Quality controls

Quality control was performed considering the following points:

-

Read Quality: Q30 Score: ≥80% of bases with Phred score ≥ 30 (error rate ≤ 0.1%), Mean Coverage: ≥50× per sample, Uniformity of Coverage: ≥90% of target exome covered at ≥ 20×.

-

Sample quality check: Low cross-sample contamination, sex concordance and relatedness were checked. No unexpected duplicates/cryptic relatedness (e.g., using PLINK/KING).

-

Variant Calling QC:

-

Mapping Quality (MAPQ): ≥30 for reliable alignment.

-

Genotype Quality (GQ): ≥20 for confident genotype calls.

-

Missingness: Variants with > 10% missing genotypes were excluded.

-

After variant calling, stringent filters were applied to prioritize pathogenic variants: Variants with MAF > 0.1% in gnomAD (especially Middle Eastern subsets), Iranome, or local controls were excluded. For pathogenicity prediction, the following thresholds were considered: CADD (≥ 20) and PolyPhen (≥ 0.5).

Pathogenic and possible pathogenic variants were described based on the ClinVar database using the method commended by the Human Genome Variation Society (http://www.hgvs.org/). Variants classification was based on the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics. Identified mutations were verified by Sanger sequencing (Codon genetics company, Iran).

We acknowledge that with 14 cases, power of study is limited, but we used the following strategies to improve detection. We focused on ultra-rare variants (MAF < 0.01%) in known leukodystrophy genes. We also compare the results with public databases, such as ClinVar.

Results

Six patients (case 1–6) were found to carry a single homozygote variant in the RARS1 gene (c.2T > C). This variant has a report in ClinVar and is regarded as a pathogenic variant. Case 6 had two additional variants in this gene, which were classified as pathogenic and VUS, respectively. However, since the c.2T > C variant was confirmed to be pathogenic, no further action was required. In addition, six cases carried homozygote variants in the GJC2, PLEKHG2, RNF220, POLR1C, DEGS1 and ACER3 genes, respectively. Finally, two patients carried a heterozygote variant in TMEM63A or TUBB4A, respectively. All patients had pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants except cases 8–10. Additional in silico predictions were conducted for these cases (Table 2).

Then, we predicted the pathogenicity of variants using bioinformatics tools (Table 2). SIFT predicts the effects of an amino acid substitution on protein function based on sequence homology and the physical characteristics of amino acids6. PolyPhen-2 is another prediction tool that shows the possible effect of amino acid substitution on the stability and function of encoded protein using structural and comparative evolutionary aspects. It implements functional annotation of single-nucleotide variants, maps coding variants to gene transcripts, extracts protein sequence annotations and structural characteristics, and constructs conservation outlines. It subsequently assesses the likelihood of the missense mutation being damaging based on a mixture of all mentioned characteristics7. Finally, CADD provides a background to integrate numerous annotations into one criterion to quantitatively rank functional, deleterious, and disease causal variants. The identified variants in the PLEKHG2, TMEM63A and RNF220 were classified as VUS. For both PLEKHG2 and RNF220 variants the CADD score and allele frequency reported by gnomeAD were suggestive of pathogenicity of the variants.

Discussion

In the current study, we reported the results of molecular analyses in 14 Iranian patients with different degrees of developmental delay in whom detected variants were associated with leukodystrophy, particularly the hypomyelinating subtype. The identified variants included two novel variants, five variants with ClinVar reports but no publications, and four variants formerly linked to leukodystrophy. The current data might strengthen the conclusion about the pathogenicity of novel variants and those without former publication. Notably, a certain RARS1 variant was found in six cases. Variants in the RARS1 gene have been recurrently detected in patients with hypomyelinating leukodystrophy12. The reported clinical manifestations included nystagmus, ataxia and spasticity12. RARS1 encodes a monomeric enzyme, namely cytoplasmic arginyl-tRNA synthetase (ArgRS). This protein has an essential role protein synthesis13. Variants in this gene have been associated with a classic form of hypomyelination presented with nystagmus and spasticity, in addition to a wider spectrum of clinical manifestations ranging from severe to mild diseases12. While in the severe form, RARS1 variants result in an early‐onset epileptic encephalopathy with brain atrophy, in milder forms myelination is preserved12. Several disease-associated RARS1 variants have been found to affect translation of the full‐length protein. For instance, the start codon has been affected in several cases of hypomyelinating leukodystrophies12. Although the precise mechanism underlying pathogenicity of RARS1 variants has not been clarified yet, a bulk of evidence from other tRNA synthetase defects suggests contribution of aminoacylation errors to cellular dysfunction14,15.

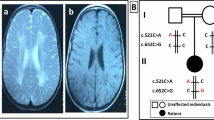

In the current study, we detected a variant in the start codon of RARS1 gene in six cases (cases 1–6). The identified RARS1 variant in the current study (c.2T > C) has been previously found in the homozygous state in two other unrelated Iranian patients manifested by developmental delay, nystagmus, seizures, psuedo-bulbar palsy and dystonia16. Besides, this variant has been shown to be segregated in two unrelated Iranian families with the similar features8. Moreover, this variant has been found in a Dutch patient in compound heterozygous state along with the c.1535G > A variant12. In the current study, microcephaly was detected in four cases out of six patients with this variant. While we did not find any association between microcephaly and occurrence of seizure or other clinical manifestations in our patients, Wan et al. have reported that patients with RARS1-related epilepsy are more likely to have microcephaly, cerebral atrophy, speech defect, and walking disability17.

GJC2 encodes Cx47, a protein that is expressed in oligodendrocytes. This protein has a role in gap junctional communication within the CNS. GJC2 variants have been associated with different neurological phenotypes, including a severe early onset dysmyelinating disorder18, a milder, later onset disorder, Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia19; and a subclinical form of leukodystrophy20. The identified GJC2 variant in case 7 (c.733T > A) was associated with the severe form of disorder.

PLEKHG2 encodes a RhoGTPase that activates CDC42 by promoting exchange of GDP for GTP on CDC42. This protein has a possible role in cell motility and neuronal network establishment in the neurons through RhoGTPase activity and actin remodeling. Pathogenic variants in this gene have been associated with leukodystrophy and acquired microcephaly with or without dystonia21. Similar to the case presented by Saini et al.21, seizure was the dominant finding in our case (case 8). However, the identified PLEKHG2 variant in our case was classified as a VUS.

TMEM63 encodes a protein which belongs to a family of mechanically activated ion channels22. As an ion channel activated by mechanical forces from cellular constituents or exterior forces, it converts cellular physical forces into biochemical signals that result in several intracellular responses23. Notably, a paternally inherited variant in this gene has been associated with infantile transient hypomyelinating leukodystrophy type 1924. Case 9 was found to have a heterozygote VUS in this gene (c.1493_1495delinsCCC). Several de novo heterozygote mutations have been found in this gene in patients with hypomyelinating leukodystrophy25,26. However, the significance of this finding in our patient should be verified.

RNF220 encodes a protein that acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase27. Mutations in this gene are associated with a type of leukodystrophy with ataxia, deafness, liver dysfunction, and dilated cardiomyopathy. Gene silencing experiment in model has shown its role in proper localization of lamin Dm0, the fly lamin B1 orthologue. Notably, its silencing has resulted in a neurodegenerative phenotype in these modes. In fact, RNF220 has a critical role in the preservation of nuclear morphology, since mutations in this gene leads to abnormalities that are usually detected in association with laminopathies9. Case 10 was found to have a variant within this gene (c.1088G > A), compatible with the clinical findings except for the presence of brain tumor which has not been reported in the literature in association with RNF220 mutations.

POLR1C gene encodes a subunit that is shared by both RNA polymerases I and III28. Different mutations in this gene result in selective modification of the availability of encoded enzymes leading to two distinct clinical conditions, namely hypomyelinating leukodystrophy and Treacher Collins syndrome28. Mechanistically, leukodystrophy-causative mutations in POLR1C, but not those associated with Treacher Collins syndrome, harm assembly and nuclear transport of POLR3, resulting in declined binding to POLR3 target genes29. The clinical findings in the case 11 carrying the c.364T > A variant was compatible with hypomyelinating leukodystrophy. Thus, it can be inferred that similar to other leukodystrophy-causative mutations, this variant leads to inappropriate assembly and nuclear import of POLR3 resulting in the reduction of availability of the complex at the chromatin28.

TUBB4A encodes a brain-specific member of the beta-tubulin family with high expression in the cerebellum, putamen, and white matter30. This gene is developmentally regulated, having the highest level of expression in the fetal brain. Being polymerized to form microtubules, it has a critical role in the axon integrity, axonal transport, and myelination. Additionally, it has a role in the modulation of morphology of CNS cells and neuronal migration31. A de novo mutation in this gene (c.745G > A) has been found to result in the hypomyelinating leukodystrophy with atrophy of the basal ganglia and cerebellum in 11 cases in a single study32. Notably, the identified mutation in case 12 (c.785G > A) is in the vicinity of this mutation.

Case 13 represented classical features of hypomyelinating leukodystrophy and had a homozygous likely pathogenic variant in the DEGS1 gene. While pathogenic DEGS1 variants are regarded as rare causes of hypomyelinating leukodystrophy33, especial attention should be paid to these variants to avoid missing the underlying cause of this disorder.

Mutations in ACER3 are regarded as very rare cause of inherited leukoencephalopathies34. This gene encodes alkaline ceramidase enzyme35. Case 14 had the c.607 C > T pathogenic variant in homozygous state. In addition, 3-Hydroxy butyric acid levels were found to be elevated in this case, possibly due to an independent mechanism.

Taken together, the cases presented above had mutations in genes being responsible for production, processing, or development of myelin and other constituents of CNS white matter, particularly oligodendrocytes and astrocytes. Thus, this study provides further supports for previously reported potential biological mechanisms contributing to the pathogenesis of leukodystrophies.

A retrospective assessment of Indian patients with a diagnosis of genetic white matter disorders has led to frequent identification of pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in the ARSA, CLN5, ABCD1, CLN6, TPP1, HEXA, and L2HGDH genes, respectively36. A similar study of leukodystrophy cases in Saudi Arabia has identified ARSA and PSAP genes as the most commonly mutated genes37. However, since the characteristics of these cohorts have been different from our cohort, it is not possible to compare our results with these cohorts.

In brief, the current study shows high prevalence of a certain RARS1 variant among Iranian patients with leukodystrophy, possibly due a founder effect. Moreover, a list of other genes was suggested as underlying causes of leukodystrophy in this population. Further studies are needed to elaborate the spectrum of genetic mutations in Iranian cases with leukodystrophy.

Our study has some limitations. First, lack of experimental validations of variants, particularly those classified as VUS, is a limitation of our study. We suggest conduction of additional assay using cellular or animal models to strengthen the evidence supporting the biological impact of these mutations. Moreover, although the majority of variants were formerly reported as pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant, the inclusion of only 14 patients without healthy individuals or non-leukodystrophy cases as controls reduces the statistical power and undermines the robustness of the associations drawn between the mutations and leukodystrophy. Increasing the sample size and including appropriate control groups would enhance the reliability of the findings. Finally, while WES could identify variants and small indels, non-coding regions, which may contain important cis-regulatory elements, might also been implicated in leukodystrophies. Thus, whole genome sequencing (WGS) can be considered for identification of these variants.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Clinvar repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar). Related accession numbers for identified variants are as following: VCV000391980.10, VCV002683827.1, VCV001680449.8, VCV000872979.3, VCV002790227.2, VCV001333094.2, VCV000548465.6, VCV000265314.27, VCV000625852.30 and VCV000548629.5.

References

Pouwels, P. J. et al. Hypomyelinating leukodystrophies: translational research progress and prospects. Ann. Neurol. 76 (1), 5–19 (2014).

Steenweg, M. E. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging pattern recognition in hypomyelinating disorders. Brain. 133 (10), 2971–2982 (2010).

Kevelam, S. H. et al. Update on leukodystrophies: a historical perspective and adapted definition. Neuropediatrics 47 (06), 349–354 (2016).

van der Knaap, M. S., Schiffmann, R., Mochel, F. & Wolf, N. I. Diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of leukodystrophies. Lancet Neurol. 18 (10), 962–972 (2019).

Ashrafi, M. et al. High genetic heterogeneity of leukodystrophies in Iranian children: the first report of Iranian leukodystrophy registry. Neurogenetics. 24 (4), 279–289 (2023).

Sim, N. L. et al. SIFT web server: predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 40(Web Server issue), W452–W457 (2012).

Adzhubei, I., Jordan, D. M. & Sunyaev, S. R. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 7:Unit7 20 (2013).

Biglari, S., Vahidnezhad, H., Tabatabaiefar, M. A., Khorram Khorshid, H. R. & Esmaeilzadeh, E. RARS1-related hypomyelinating leukodystrophy-9 (HLD-9) in two distinct Iranian families: case report and literature review. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 12 (4), e2435 (2024).

Sferra, A. et al. Biallelic mutations in RNF220 cause laminopathies featuring leukodystrophy, ataxia and deafness. Brain. 144 (10), 3020–3035 (2021).

Ferreira, C., Poretti, A., Cohen, J., Hamosh, A. & Naidu, S. Novel TUBB4A mutations and expansion of the neuroimaging phenotype of hypomyelination with atrophy of the basal ganglia and cerebellum (H-ABC). Am. J. Med. Genet. Part. A. 164A (7), 1802–1807 (2014).

Dolgin, V. et al. DEGS1 variant causes neurological disorder. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. EJHG. 27 (11), 1668–1676 (2019).

Mendes, M. I. et al. RARS1-related hypomyelinating leukodystrophy: expanding the spectrum. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. ;7(1), 83–93 (2020).

Kim, J. H., Ahn, T. J., Cho, Y., Hwang, D. & Kim, S. Evolution of the multi-tRNA synthetase complex and its role in cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 294 (14), 5340–5351 (2019).

Abbott, J. A., Francklyn, C. S. & Robey-Bond, S. M. Transfer RNA and human disease. Front. Genet. 5, 158 (2014).

Yao, P. & Fox, P. L. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in medicine and disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 5 (3), 332–343 (2013).

Rezaei, Z. et al. Hypomyelinating leukodystrophy with spinal cord involvement caused by a novel variant in RARS: report of two unrelated patients. Neuropediatrics 50 (2), 130–134 (2019).

Wan, L. et al. RARS1-related developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Epilepsia Open. 8 (3), 867–876 (2023).

Uhlenberg, B. et al. Mutations in the gene encoding gap junction protein α12 (connexin 46.6) cause Pelizaeus-Merzbacher–like disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75 (2), 251–260 (2004).

Orthmann-Murphy, J. L. et al. Hereditary spastic paraplegia is a novel phenotype for GJA12/GJC2 mutations. Brain 132 (2), 426–438 (2009).

Abrams, C. K. et al. A new mutation in GJC2 associated with subclinical leukodystrophy. J. Neurol. 261, 1929–1938 (2014).

Saini, A. G., Sankhyan, N. & Vyas, S. PLEKHG2-associated neurological disorder. BMJ Case Rep. ;14(7). (2021).

Murthy, S. E. et al. OSCA/TMEM63 are an evolutionarily conserved family of mechanically activated ion channels. eLife. 7 (2018).

Douguet, D. & Honoré, E. Mammalian mechanoelectrical transduction: structure and function of Force-Gated ion channels. Cell. 179(2), 340–354 (2019).

Siori, D. et al. A TMEM63A nonsense heterozygous variant linked to infantile transient hypomyelinating leukodystrophy type 19? Genes (Basel). ;15(5). (2024).

Yan, H. et al. Heterozygous variants in the mechanosensitive ion channel TMEM63A result in transient hypomyelination during infancy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 105 (5), 996–1004 (2019).

Tonduti, D. et al. Spinal cord involvement and paroxysmal events in infantile onset transient hypomyelination due to TMEM63A mutation. J. Hum. Genet. 66 (10), 1035–1037 (2021).

Kong, Q. et al. RNF220, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets Sin3B for ubiquitination. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 393 (4), 708–713 (2010).

Thiffault, I. et al. Recessive mutations in POLR1C cause a leukodystrophy by impairing biogenesis of RNA polymerase III. Nat. Commun. 6, 7623 (2015).

Thiffault, I. et al. Recessive mutations in POLR1C cause a leukodystrophy by impairing biogenesis of RNA polymerase III. Nat. Commun. 2015/07 (07), 7623 (2015).

Kancheva, D. et al. Mosaic dominant TUBB4A mutation in an inbred family with complicated hereditary spastic paraplegia. Mov. Disord. 30 (6), 854–858 (2015).

Gavazzi, F. et al. The natural history of variable subtypes in pediatric-onset TUBB4A-related leukodystrophy. Mol. Genet. Metab. 144(3), 109048 (2025).

Simons, C. et al. A de Novo mutation in the β-tubulin gene TUBB4A results in the leukoencephalopathy hypomyelination with atrophy of the basal ganglia and cerebellum. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92 (5), 767–773 (2013).

Wong, M. S. T. et al. DEGS1 -related leukodystrophy: a clinical report and review of literature. Clin. Dysmorphol. 32 (3), 106–111 (2023).

Dehnavi, A. Z. et al. ACER3-related leukoencephalopathy: expanding the clinical and imaging findings spectrum due to novel variants. Hum. Genomics. 15 (1), 45 (2021).

Mao, C. et al. Cloning and characterization of a novel human alkaline ceramidase. A mammalian enzyme that hydrolyzes phytoceramide. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (28), 26577–26588 (2001).

Manisha, K. Y. et al. Spectrum of leukodystrophy and genetic leukoencephalopathy in Indian population diagnosed by clinical exome sequencing and clinical utility. Neurol. Genet. 10 (5), e200190 (2024).

Alfadhel, M. et al. The leukodystrophy spectrum in Saudi arabia: epidemiological, clinical, radiological, and genetic data. Front. Pediatr. 9, 633385 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.F. and S.K. evaluated patients’ reports. S.G.F. wrote the manuscript. M.M. supervised the study. All the authors read and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent has been obtained from all patients. Ethical approval for this study has been obtained from the Ethical Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fathi, M., Khalilian, S., Miryounesi, M. et al. Overview of genetic variants in a cohort of Iranian patients with leukodystrophy. Sci Rep 15, 21898 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07597-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07597-z