Abstract

Anemia is among the most common hematologic problems, defined as a hemoglobin level below 13 g/dl for males and below 12 g/dl for adult non-pregnant females. Anemia is caused by several factors and has the highest prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. However, there is limited research on the prevalence of anemia and its associated factors in hospitalized patients in the Somali Region of Ethiopia. An institution-based Cross-sectional study design was conducted from July 01 to August 30, 2024, at Garbo Primary Hospital: all medical patients who visited Garbo Primary Hospital and who had CBC tests were selected using a systematic random sampling method. The Data was collected using structured questionnaires and checklists. Data was coded and entered into EpiData version 4.6 and exported into STATA version 17, Texas 77845 USA, for analysis. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression were used to identify factors associated with anemia at a 95% confidence interval, and a P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A total of 369 patients participated in this study, and among those, 284 (76.96%) have been diagnosed with anemia using their Hgb label. Among those patients with anemia, 139 (48.94%) had mild anemia, 109 (38.38%) moderate anemia, and 36 (12.68%) severe anemia. Being female, currently smoking cigarettes, and being patient with disease comorbidity were found to be statistically significant for the odds of development of anemia. The prevalence of anemia among patients attending Garbo Primary Hospital was found to be 76.96%. Those interventions, including programs to help women quit smoking, as well as targeted nutritional support, could be recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anemia is among the most common hematologic problems, which is defined as according to WHO hemoglobin (Hgb) levels below 13 g/dl for males and below 12 g/dl for adult non-pregnant females1.Anemia can be classified in different ways of classification, which can be classified based on the severity of anemia as mild, moderate, and severe based on Hgb value2,3. The other way of classification of anemia is based on morphology, microcytic hypochromic, macrocytic, and normocytic normochromic; among which the most common morphologic pattern is microcytic hypochromic anemia4. The causes of anemia are complex, including nutritional deficiency, infection, and medical conditions, and among those, the most common one is iron deficiency anemia5,6.

In addition to anemia, patients can present with varied clinical manifestations, even though symptoms vary based on cause, onset, premorbid health condition, and severity of anemia. Most patients are presented with excessive fatigability, dyspnea, lack of energy, and lack of concentration7. Anemia is confirmed by clinical signs and symptoms associated with anemia, which are tested in the laboratory utilizing complete blood count (CBC) with a low HGB count below the WHO cutoff point8.

Anemia has negative impacts on both overall survival and health-related quality of life, especially in certain populations like elderly patients greater than 60 years of age, pregnant women, and if the cause of anemia is due to chronic inflammation9. Anemia increases the risk of recurrent falls, muscle weakness, and poor physical performance, which is more pronounced in elderly patients and increases hospitalization and length of hospital stay10. According to a WHO report published in 2023, anemia affects 1.8 billion people worldwide, with the highest prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, and children and women are affected disproportionately because of nutritional deficiency and rapid metabolic growth of children and reproductive disorders including menstruation bleeding and chronic disease in women tends to be the cause for the development of anemia11,12,13.

The global prevalence of anemia in 2021 was 24.3% across all age groups, which was higher than the 1990 global burden and needs proper attention for prevention and treatment since most causes of anemia are treatable6. Even in developed countries, anemia is still a major problem accounting about 2.2% of the population, or 6.2 million adults > 20 years in the USA, is affected by anemia14. In contrast to other parts of the world, Africa is disproportionately affected by anemia for a variety of reasons, which include inadequate diet, poverty, and frequent exposure to infections in children and pregnant women, Geophagy is the practice of eating earth or soil-like substances in rural residences, which is also another factor that exposes nutritional deficiencies that lead to the development of anemia15,16,17. According to a 2021 sub-Saharan study among adult married women, the prevalence of anemia was almost 50%, which causes health and health-related disabilities18.

In 2016 Ethiopian demographic health survey reported that the national prevalence of anemia was 24% and varies across regions, with which Somali region being the most affected region, accounting for 59.5%, followed by the Afar region at 44.7%19. In the 2023 institutional Amhara region study among hypertensive patients, anemia is among the major health problems, accounting for 17.6%, and needs proper prevention and treatment to reduce health costs20. Again, in a 2019 population-based study, anemia is still a major problem in all age groups, which accounts for 23% of women of reproductive age, 56% of children under the age of 5 years, and 18% of adult men21. Although there is no regional or institution-based study on the prevalence of anemia among medical patients, it was found that 63.8% of pregnant patients in a rural part of Jigjiga city, Eastern Ethiopia, in the Somali region22.

Anemia is among the most common medical problems that often encountered in medical practice at Garbo Primary Hospital, though the exact burden of the problem is not known. Even though this hospital started service within the past 3 years, there are lots of anemia cases to the extent of requiring blood transfusion. So the exact burden of the disease and associated factors with anemia should be known, and appropriate intervention should be done at the community, hospital, regional as well and national levels.

In addition to this, since this hospital is far from the center will generate new information on prevalence and associated factors to tackle it to give attention to the problem, and increase the availability of essential drugs for the treatment of anemia and blood transfusion service. Therefore the research findings will be used as a benchmark to plan, monitor, and control the existing and future level of patient care at this hospital and community level additionally, the study will serve as a base for further studies and policymakers regarding anemia for community to create awareness about prevention of anemia and to visit hospital early and to manage appropriately. This study aimed and conducted to assess the prevalence and associated factors of anemia among medical patients who visited Garbo Primary Hospital.

Methods

Study area

The study was carried out in Garbo Primary Hospital. The hospital is one of the primary hospitals in the Nogob zone in the Somali region of Ethiopia. The hospital is found in Garbo Woreda, geographically located in the Nogob Zone, bordered by Segeg Woreda to the northwest, the Degehabur Zone to the north, the Korahe Zone to the east, the Gode Zone to the south, and Dihun Woreda to the west. Its coordinates are approximately 3° 59′ 22″ N latitude and 41° 51′ 53″ E longitude. The climate is classified as a hot desert. Garbo Primary Hospital serves as the sole district hospital for the Nogob Zone, supporting a population of over 400,000 individuals. Eleven health centers within the zone refer patients to Garbo, which offers a comprehensive range of departments, including internal medicine, surgery, gynecology and obstetrics, pediatrics and child health, radiology, and ophthalmology. It is located approximately 320 km from Jijiga town, the capital of the Somali Region of Ethiopia, and 160 km from Degehabour town. Garbo Primary Hospital plays a crucial role in providing accessible and essential patient care for the region.

Study design and period

An institution-based cross-sectional study design was conducted from July 01, 2024, to August 30, 2024.

Population and sampling

Source population

All patients who visited the Garbo primary hospital within the study period were the source population.

Study population

All patients who had CBC tests within the study period were the study population.

Study subjects

Selected patients who had CBC tests within a study period and fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included in this study.

Sample size determination and sampling technique

Sample size determination

The sample size is determined using a single population proportion formula by using a study conducted on the prevalence of anemia among medical patients at Harar Hospital, East Ethiopia, in 2023 G.C. Prevalence of anemia is considered as an independent predictor, from that study prevalence of anemia was 64.8% in Harar23, by using 95% level of confidence and 5% level of precision, the total sample size was determined as follows.

n = 1.962 * 0.648(1–0.648)/0.052 = 351 and that a 5% non-response rate was anticipated and added to the initial calculation, resulting in a final sample size of 369 patients.

where n = minimum sample size; Z (α/2) = the desired level of statistical significance (1.96); P (1 − p) = A measure of variability. Therefore, the final sample size was 369 patients.

Sampling technique

All eligible patients who had a CBC from July 01, 2024, to August 30, 2024, at Garbo Primary Hospital were considered study subjects. A simple random sampling was employed to select 369 study participants. Each patient has been selected using a systematic random sampling method.

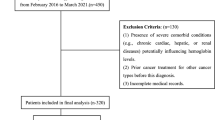

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

All medical patients who visited Garbo Primary Hospital who had CBC tests.

Exclusion criteria

-

Patient with incomplete charts

-

Those patients who did not communicate

-

Those patients are unwilling to participate

Description of variables

-

Dependent variable

-

Prevalence of Anemia

-

Independent variables

-

Sociodemographic (Age, Sex, Residency, Socioeconomic status, and Educational level)

-

Behavioral factors-Smoking, alcohol, diet (cow and camel milk intake)

-

Drugs like highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), metformin, anticoagulants, and others

-

The presence of comorbidity

-

Nutritional status

-

Herbal medicine intake

-

Family history of anemia

Operational definition and definition of terms

Anemia: those patients who had HGB < 13 g/dl for males and HGB < 12 g/dl for non-pregnant adult females2.

Severity of anemia: classified as mild anemia when the HGB is (10.0–11.9 g/dl), moderate (7.0–9.9 g/dl), and severe (HGB < 7.0 g/dl)24,25.

Morphologic classification: normocytic normochromic, microcytic hypochromic, normocytic hypochromic, and macrocytic normochromic RBC26.

The burden of Anemia: if the prevalence of anemia is greater than 40% major public health problem; if it lies between 20 and 40% is a medium-level public health problem, and if the prevalence is less than 20%, it is a mild public health problem27.

Data collection methods

Data collection instruments

The required number of patients was selected by using simple random sampling, and then the selected patients were interviewed. Since the records are written in English and data collectors can read and write English, the tool is not translated into the local language. Data related to anemia were collected from laboratory reports. Other data, such as socio-demographic, behavioral factors, comorbidities, and drug intake history, were collected from the patient’s medical record. Sociodemographic factors and other pertinent information were not documented from the medical record and were obtained from patients or attendants through interviews and a well-prepared checklist.

The data collection tool was developed based on the study objectives (Supplementary file 1). The data collection process was conducted by trained data collectors, including three General Physicians and two nurses who were supervised by the Principal Investigator.

Data quality assurance

A pretest was done among 5% of the sample size at Jigjiga University Hospital, and the necessary modifications were made to the data collection tool based on the findings. Data was checked for accuracy and consistency by the Principal Investigator daily during the data collection period.

Data management and analysis

Data was checked for completeness every day during data collection. It was arranged, cleaned, and coded; the collected data were entered into EpiData version 4.6 and exported to STATA version 17. Texas 77,845 USA was used for analysis. Appropriate descriptive analyses were performed to describe the study population characteristics in terms of the variables by calculating frequencies and proportions, and results were presented in tables and pie charts.

A bivariate logistic regression model was used to see the association between the predictor and outcome variables. The complete blood count, including hemoglobin (Hgb) and mean corpuscular volume (MCV), was determined to identify the patients with anemia. Henceforth, multivariable logistic regression analysis was employed by selecting only variables with a P value < 0.25 in the bivariate analysis. Odds ratio with 95% CI was used to measure the strength between dependent and independent variables at P-value < 0.05 to determine the level of statistical significance. To determine an association between dependent and independent variables adjusted odds ratio was entered into multivariate logistic regression one by one to control for potential confounders and to detect the determinants of independent variables with the outcome variable. Variables with a p-value less than 0.05 with 95% CI in multivariate regression were declared to be potential predictors for anemia.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 369 patients participated in this study. Most of the study participants were female, accounting for 237 (64.23%). The mean (± SD) age of the participants was 34.9 years, with 95% CI of (33.19–36.63), and a minimum age of 15 and maximum of 87 year, and most of the participants were aged ≤ 24 years, 119 (32.25%), followed by age 25–34 years, 95 (25.75%). The majority of the participants, 260 (70.46%) of participants live in rural areas. More than half of the study participants 210 (56.91%) were unable to read and write level of education and followed by able to read and write 101 (27.37%) and the majority of the study participants were farmers 241 (65.31%) followed by students 53 (14.36%) (Table 1).

Behavioral and clinical characteristics of the study participants

Among 369 participants, 52 (14.09%) are current smokers of cigarettes, and most of the participants have 255, 69.11%) have a khat chewing history, and most of the participants were camel milk users, 315 (85.37%) (Table 2).

Early camel milk exposure: indicates when infants or young children drink camel milk, especially in societies where it is a customary food source, Underweight: If a person’s body weight is much less than what is deemed healthy for their height or a body mass index (BMI) of less than 18.5, Normal Weight: a range of acceptable weights for a specific height, indicating a healthy diet and general well-being or a BMI of 18.5 and 24.9, Overweight: A body weight exceeds the healthy range for their height, indicating excess body fat or BMI of 25–29.9.

Severity of anemia of the study participants

Among the total of 369 study participants, anemia was seen in 284 (76.96%) of the study participants. Among those patients having anemia, 139 (48.94%) were developing mild anemia, 109 (38.38%) moderate anemia, and 36 (12.68%) severe anemia. In this finding, the prevalence of Anemia was found to be 76.96%, the mean (± SD) hemoglobin of participants was 10.46 with a 95% CI of (10.21–10.71) and the mean (± SD) MCV of participants was 78.68 with 95% CI of (77.61–79.75) (Fig. 1).

Factors associated with the prevalence of anemia

In multivariable logistic regression analysis, being female, currently cigarette smoking, and those having disease comorbidity were statistically significant variables of the development of anemia among patients attending Garbo primary hospital, with a p-value of < 0.001, < 0.001, and 0.037, respectively. Females in sex were 5.80 times more likely to develop anemia compared with males [AOR = 5.80 (95% CI = 2.69–12.51)]. Participants with current history of cigarette smoking were 6.37 more likely to be exposed for anemia than those who had no history of smoking [AOR = 6.37 (95% CI = (2.27–17.89))], and those having comorbid disease were 3.49 times more likely to be exposed for anemia than those having no comorbid disease [AOR = 3.49 (95% CI = (1.08–11.29))] (Table 3).

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to determine the prevalence and factors associated with Anemia among patients attending Garbo Primary Hospital, Somali region of Ethiopia, South-Eastern Ethiopia. In this finding, the prevalence of Anemia was found to be 76.96%, the mean (± SD) hemoglobin of participants was 10.46 with a 95% CI of (10.21–10.71), and the mean (± SD) MCV of participants was 78.68 with a 95% CI of (77.61–79.75). The finding of the MCV value indicates that the microcytic anemia could be due to iron deficiency anemia, so further nutritional assessment is necessary to prevent anemia from occurring. Among these anemic patients, 48.9% had mild anemia, 38.38% had moderate anemia, and 12.68% had severe anemia. In this finding, the prevalence of Anemia was 76.96%, which is in line with a study conducted at Creek General Hospital, where the prevalence of anemia was 71%28.

In this finding, the prevalence of Anemia was found to be 76.96% with a CI of 72.65–81.28, which is higher than a study conducted from secondary data of the Gilgle Gibi research center, which showed that the overall prevalence of anemia was 40.9%29. This discrepancy might be due to the difference in the study population, which they conducted on normal individuals, while patients visiting the primary hospital were the source population. And also this finding is higher than a study conducted in Debre Tabor comprehensive specialized hospital (DTCSH), where the prevalence of anemia was 29.81%30, and a study conducted at TASH, where the prevalence of anemia was 23%31 and 18.1%32 in a study conducted in Bale zone hospitals. This discrepancy might be due to the difference in the population under study, where we conducted our study on all patients visiting the primary hospital, and in other studies conducted in DTCSH, Bale zone hospitals, and Tibebe Ghion Specialized Hospital (TASH), the source population was diabetes mellitus and patients with malignancy, respectively.

On the other hand, this study is higher than a study conducted in hospital-admitted patients in eastern Ethiopia where the prevalence of anemia is 64.8%23, in public hospitals of Addis Ababa the prevalence of anemia, was found to be 53.5%33, in UoGCSH the prevalence of anemia among CKD patients was 64.5%34, and a study conducted in Italy showed that the prevalence of anemia among internal medicine admitted patients was 58.1%35 and similarly in Italy Padova university hospital anemia in hospitalized patients was 43.9%36.

Based on this study, being female was found to be strongly associated with the prevalence of anemia. In this study, females were 5.80 times more likely to develop anemia than male participants. This finding is comparable with the findings of the cross-sectional study conducted in Bale general hospitals32 where females were three times more likely to develop anemia than males and a study conducted in northern Ethiopia states that females were more likely to develop anemia than males37, while this finding is not comparable with the study conducted in Gelemso general hospital38 where being male were more exposed for anemia than females. This discrepancy might be due to the difference in the source of the population, where the study was conducted in diabetic patients, since males are more prone to metabolic syndrome, which leads males to be more prone to diabetes mellitus, and leads males to develop anemia than females.

Based on this study, currently, smoking was found to be strongly associated with the development of anemia. Patients with current smoking had 6.37 times higher odds of developing anemia than those who never smoked cigarettes because smoking produces oxidative stress by generating free radicals that damage red blood cells and cause anemia also smoking decreases nutritional appetite resulting in the development of anemia and females smoking decreases vitamin that absorbs iron from diet resulted in iron deficiency anemia and smoking lowers vitamin C levels in the body, which are important for the absorption of iron39. Smoking causes persistent blood loss by harming the lining of the intestines and stomach. The body’s capacity to absorb iron from the diet is reduced by smoking40,41,42. Other nutrient deficits brought on by smoking include those in vitamins B12 and folate, which are critical for the synthesis of red blood cells. This result is comparable to a cross-sectional study conducted to identify the correlations between anemia and smoking42.

According to this study, the presence of comorbid disease was found to be strongly associated with the development of anemia. Those patients having a history of the presence of comorbid disease had 3.49 times higher odds of developing anemia than those who did not have a history of comorbid disease. This finding is comparable with the study conducted among admitted patients in Harari region of Ethiopia showed that patients having non-communicable disease were associated with the development of anemia23 and also similar with a study conducted in the USA where patients who had comorbidity were 1.74 odds of greater prevalence of anemia than those who did not have disease comorbidity43.

Conclusions

In this study, the prevalence of anemia among patients attending Garbo Primary Hospital was found to be 76.96%, which was very high. Therefore, early screening, diagnosing, and providing treatment, and also providing preventive measures are very important in these regions to decrease the burden of the disease and unwanted treatment costs of patients when seeking medical therapy after the disease has progressed, which can improve the quality of life of patients and improve public health concerns. Being female, current smoking status, and presence of comorbid disease were independent predictors of anemia. Therefore, interventions including programs to help women quit smoking, as well as targeted nutritional support, could be recommended.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The present study identifies anemia based on the Hgb level and MCV to identify other risk factors for anemia, such as vitamin B12 level, which is one of the strengths of our study. However, this study has some limitations, as it was a cross-sectional study, so the causal relationship between factors and anemia must be interpreted with caution. The other limitation is that the onset of anemia involves diverse and complex mechanisms, and chronic anemia and iron deficiency anemia cannot be identified by the present study.

Data availability

All the data regarding the findings of this study are available within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CBC:

-

Complete blood count

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- DTCSH:

-

Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- GI:

-

Gastro intestine

- HCT:

-

Hematocrit

- HGB:

-

Hemoglobin

- HIV:

-

Human immune virus

- MCHC:

-

Mean cell hemoglobin concentration

- MCV:

-

Mean cell volume

- TASH:

-

Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital

- RBC:

-

Red blood cell

- RDW:

-

Red cell distribution width

- UoGCSH:

-

University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Cappellini, M. D. & Motta, I. Anemia in clinical practice: Definition and classification: does hemoglobin change with aging? In Seminars in Hematology 261–269 (Elsevier, 2015).

Akbarpour, E. et al. Anemia prevalence, severity, types, and correlates among adult women and men in a multiethnic Iranian population: The Khuzestan Comprehensive Health Study (KCHS). BMC Public Health 22(1), 168 (2022).

Alamneh, T. S., Melesse, A. W. & Gelaye, K. A. Determinants of anemia severity levels among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia: Multilevel Bayesian statistical approach. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 4147 (2023).

Okia, C. C. A. B. et al. Prevalence, morphological classification, and factors associated with anemia among pregnant women accessing antenatal clinic at Itojo Hospital, South Western Uganda. J. Blood Med. 10, 351–357 (2019).

WHO. Accelerating anaemia reduction: A comprehensive framework for action (2023).

GBD 2021 Anaemia Collaborators. Prevalence, years lived with disability, and trends in anaemia burden by severity and cause, 1990–2021: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Hematol. 10, e713–e734 (2023).

Weckmann, G., Kiel, S., Chenot, J. F. & Angelow, A. Association of anemia with clinical symptoms commonly attributed to anemia—analysis of two population-based cohorts. J. Clin. Med. 12, 921 (2023).

Martinsson, A. et al. Anemia in the general population: Prevalence, clinical correlates, and prognostic impact. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 29, 489–498 (2014).

Wouters, H. J. et al. Association of anemia with health-related quality of life and survival: A large population-based cohort study. Haematologica 104(3), 468 (2018).

Guralnik, J. et al. Unexplained anemia of aging: Etiology, health consequences, and diagnostic criteria. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 70(3), 891–899 (2022).

Pasricha, S. R. & Moir-Meyer, G. Measuring the global burden of anaemia. Lancet Hematol. 10, e696–e697 (2023).

Sun, J., Wu, H., Zhao, M., Magnussen, C. G. & Xi, B. Prevalence and changes of anemia among young children and women in 47 low- and middle-income countries, 2000–2018. EClinicalMedicine 41, 101136 (2021).

Alem, A. Z. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with anemia in women of reproductive age across low- and middle-income countries based on national data. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 20335 (2023).

Benjamin, E. J. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 139, e56–e528 (2019).

Obeagu, E. I., Opoku, D. & Obeagu, G. U. Burden of nutritional anaemia in Africa: A review. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. 10(2), 160–163 (2023).

Davies, T. C. Current status of research and gaps in knowledge of geophagic practices in Africa. Front. Nutr. 9, 1084589 (2023).

Decaudin, P. et al. Prevalence of geophagy and knowledge about its health effects among native Sub-Saharan Africans, Caribbean, and South American healthy adults living in France. Eat. Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 25, 465–469 (2020).

Zegeye, B. et al. Prevalence of anemia and its associated factors among married women in 19 sub-Saharan African countries. Arch. Public Health 79, 1–12 (2021).

ICF. csaCEa. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (2016).

Gela, Y. Y. et al. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among adult hypertensive patients in Referral Hospitals, Amhara Regional State. Sci. Rep. 13, 14239 (2023).

Tadesse, A. W. et al. Anemia prevalence and etiology among women, men, and children in Ethiopia: A study protocol for a national population-based survey. BMC Public Health 19(1), 1–8 (2019).

Bereka, S. G., Gudeta, A. N., Reta, M. A. & Ayana, L. A. Prevalence and associated risk factors of anemia among pregnant women in rural part of JigJiga City, Eastern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. J. Pregnancy Child Health 4, 2 (2017).

Yusuf, M. U. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of anemia among hospital admitted patients in Eastern Ethiopia. J. Blood Med. 14, 575–588 (2023).

Muchie, K. F. Determinants of severity levels of anemia among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia: Further analysis of the 2011 Ethiopian demographic and health survey. BMC Nutr. 2, 1–8 (2016).

Tesema, G. A. et al. Prevalence and determinants of severity levels of anemia among children aged 6–59 months in sub-Saharan Africa: A multilevel ordinal logistic regression analysis. PLoS ONE 16(4), e0249978 (2021).

Saxena, R., Chamoli, S. & Batra, M. Clinical evaluation of different types of anemia. World 2(1), 26–30 (2018).

Stauder, R. & Thein, S. L. Anemia in the elderly: Clinical implications and new therapeutic concepts. Haematologica 99(7), 1127 (2014).

Bashir, F. et al. Anemia in hospitalized patients: Prevalence, etiology, and risk factors. J. Liaquat Univ. Med. Health Sci. 16(2), 80–85 (2017).

Tesfaye, T. S., Tessema, F. & Jarso, H. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among “apparently healthy” urban and rural residents in Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. J. Blood Med. 11, 89–96 (2020).

Engidaw, M. T. & Feyisa, M. S. Prevalence of anemia and its associated factors among adult diabetes mellitus patients at Debre Tabor General Hospital, Northcentral Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 13, 5017–5023 (2020).

Kifle, E., Hussein, M., Alemu, J. & Tigeneh, W. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among newly diagnosed patients with solid malignancy at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, radiotherapy center, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Adv. Hematol. 2019(1), 8279789 (2019).

Solomon, D. et al. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among adult diabetic patients attending Bale zone hospitals, South-East Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 17(2), e0264007 (2022).

Alemu, B., Techane, T., Dinegde, N. G. & Tsige, Y. Prevalence of anemia and its associated factors among chronic kidney disease patients attending selected public hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Institutional-based cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nephrol. Renovascular Dis. 14, 67–75 (2021).

Adera, H., Hailu, W., Adane, A. & Tadesse, A. Prevalence of anemia and its associated factors among chronic kidney disease patients at University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: a Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Nephrol. Renovascular Dis. 12, 219–228 (2019).

Zaninetti, C. et al. Prevalence of anemia in hospitalized internal medicine patients: Correlations with comorbidities and length of hospital stay. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 51, 11–17 (2018).

Randi, M. L. et al. Prevalence and causes of anemia in hospitalized patients: Impact on disease outcome. J. Clin. Med. 9(4), 950 (2020).

Hailu, N. A., Tolessa, T., Gufue, Z. H., Tsegay, E. W. & Tekola, K. B. The magnitude of anemia and associated factors among adult diabetic patients in Tertiary Teaching Hospital, Northern Ethiopia, 2019, a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 15(11), e0240678 (2020).

Tujuba, T., Ayele, B. H., Fage, S. G. & Weldegebreal, F. Anemia among adult diabetic patients attending a general hospital in Eastern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional Study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 14, 467–476 (2021).

Vivek, A., Kaushik, R. M. & Kaushik, R. Tobacco smoking-related risk for iron deficiency anemia: A case-control study. J. Addict. Dis. 41(2), 128–136 (2023).

Ghio, A. J., Pavlisko, E. N., Roggli, V. L., Todd, N. W. & Sangani, R. G. Cigarette smoke particle-induced lung injury and iron homeostasis. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 17, 117–140 (2022).

Pateva, I. B. et al. Effect of maternal cigarette smoking on newborn iron stores. Clin. Res. Trials 1(1), 4 (2015).

Waseem, S. M. A. & Alvi, A. B. Correlation between anemia and smoking: Study of patients visiting different outpatient departments of Integral Institute of Medical Science and Research, Lucknow. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 10(2), 149 (2020).

Gandhi, S. J., Hagans, I., Nathan, K., Hunter, K. & Roy, S. Prevalence, comorbidity, and investigation of anemia in the primary care office. J. Clin. Med. Res. 9(12), 970 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the data collectors, and we would like to extend our sincere thanks to all of the study participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.Ayen.: designed the study, F.N.G., G.Y.T., T.A.M., G.A.Y., R.M.A., S.S.A., and M.A.I. analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript, T.Y.T., M.M.F., W.A.N., and A.A.A.: participated in the designing of the study and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval and an ethical clearance certificate were obtained from Debre Tabor University, College of Health Sciences Ethics Committee, with reference number CBE 305/2016. Written informed consent was obtained from study participants and the parents of the study participants whose ages were below 16 years for the interview. This study was done in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Study participants were also told that they had the full right to refuse participation in the interview at any time, and the confidentiality and privacy of study participants were maintained.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ayen, A.A., Tarekegn, G.Y., Moges, T.A. et al. Magnitude and determinants of anemia among patients at Garbo Primary Hospital, Somali Region of Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 28179 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07914-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07914-6