Abstract

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, prevention and control workers have been exposed to heavy workloads at high risk of infection, which has led to mental health issues such as anxiety, insomnia, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). A cross-sectional study was conducted among 346 prevention and control workers covering 46 cities in 14 provinces in China from February to March 2020. Non-probabilistic convenience sampling and snowball sampling were used to collect data, including data on fatigue, sleep quality and PTSD symptoms. Descriptive analysis, chi-square tests, Mann‒Whitney U tests, Kruskal‒Wallis H tests, ordered logistic regression and binary logistic regression analysis were employed. The fatigued state of prevention and control workers was mild, and most of them experienced decreased sleep quality. There was a statistically significant difference in PTSD levels between workers who had direct contact with COVID-19 patients and those who did not (P < 0.001). The PTSD scores of workers with different degrees of fatigue and sleep quality significantly differed from those before the epidemic (all P < 0.001). Moreover, workers in direct contact with COVID-19 patients had fewer PTSD symptoms (P = 0.002). Workers with more severe fatigue had more PTSD symptoms than before the epidemic. On the other hand, workers with poor sleep quality had more PTSD symptoms than before the epidemic did (all P < 0.001). Considering decreased sleep quality and high PTSD scores, it is necessary to arrange working hours rationally and conduct professional psychological counselling to ensure the physical and mental health of prevention and control workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global outbreak of COVID-19, declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization, has profoundly impacted societies worldwide, extending far beyond physical health consequences. A critical and pervasive secondary effect has been its significant toll on global mental health1. While populations universally face challenges, certain groups bear a disproportionate burden. Among those most acutely affected, particularly during the initial critical phases of the pandemic, were the frontline epidemic prevention and control workers2. The sheer scale and severity of the crisis were unprecedented; by February 2020, the death toll from COVID-19 had already surpassed the combined fatalities of both the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreaks3. Compounding the challenge, the SARS-CoV-2 virus exhibits high transmissibility, potential for severe illness, and a demonstrated capacity for rapid mutation during replication, facilitating its adaptation and spread4. In response to this extraordinary threat, massive mobilization occurred, with countless prevention and control workers deployed from diverse regions to the front lines. Their tireless efforts were undeniably pivotal in containing the virus and mitigating its spread5. However, this vital work came at an immense personal cost6. Facing relentless workloads, constant exposure risks, and extreme psychological stressors, these personnel encountered unprecedented threats to their psychological well-being7,8. Consequently, a significant concern emerged: frontline workers are at heightened risk of developing debilitating conditions such as profound fatigue, pervasive sleep disturbances, and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)9. Understanding the scope, nature, and drivers of this mental health crisis among epidemic prevention workers is therefore not only crucial for supporting this essential workforce but also for building resilience for future public health emergencies.

Previous studies have revealed increased rates of negative psychological effects such as depression and anxiety in individuals who play a crucial role in managing pandemics, especially prevention and control workers10. Wong et al. strongly advocated for attention to the mental health of prevention and control workers, as she was an emergency department physician and witnessed life-threatening traumatic events with other medical workers resulting in severe fatigue and insomnia11. Similarly, in a systematic review and meta-analysis, Aymerich et al. conducted research focused on health workers’ mental health and inferred that during the global COVID-19 pandemic, insomnia and anxiety problems were prevalent among healthcare workers in hospitals, and even symptoms of PTSD were very likely prevalent12. According to Tracy et al., the unusual threat and catastrophic nature of the COVID-19 epidemic has posed great psychological challenges to those involved in epidemic prevention and control. In severe cases, it may lead to PTSD13.

However, owing to heavy epidemic prevention efforts, in-depth research with specific data support has not been conducted. Incomplete understanding of COVID-19 and excessive psychological load have caused epidemic prevention and control workers to experience frequent and persistent sleep disorders, such as difficulty falling asleep, waking up early, nightmares, and difficulty maintaining sleep, and cannot meet normal needs, including physiological and physical recovery needs14. As the demand for healthcare will continue to increase in the future and infectious disease epidemics will become more frequent, maintaining and promoting the physical and mental health of prevention and control workers will become increasingly important15,16. In summary, researchers plan to investigate the health status and influencing factors of COVID-19 prevention and control workers and provide health interventions for them in future outbreaks.

This study focused on the physical and mental health problems of COVID-19 prevention and control workers in the early stage of the COVID-19 epidemic and investigated the influencing factors and causes of these problems by investigating fatigue, sleep quality and PTSD symptoms. It is necessary to assess these situations and provide evidence for the challenges in infectious disease prevention and control17.

Methods

Participants

This study focused on frontline epidemic prevention and control workers operating during the peak transmission period of COVID-19 in China (February–March 2020). The final analytical sample included 346 prevention workers.The inclusion criteria comprised: (a) age ≥ 18 years; (b) active engagement in medical/health institutions or community-based epidemic response; and (c) professional roles categorized as: (a) clinical healthcare personnel (physicians, nurses), (b) technical staff at disease control institutions, or (c) community prevention coordinators. Exclusion criteria excluded: (a) administrative staff without direct epidemic-facing duties; (b) personnel with less than 6 months of work experience; and (c) individuals with pre-existing severe psychiatric or neurological disorders.

The three groups of workers are the main forces at the forefront of COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control to control the spread of the epidemic. However, the workplace and the specific division of labor vary. Doctors and nurses work mainly in hospitals and isolation wards. The main responsibility is to be responsible for the diagnosis and treatment of the disease and to treat and care for the patients. Moreover, disease monitoring and prevention are needed. Disease prevention and control workers mainly work in quarantine hotels, stations, airports and other public places to conduct inspections. Moreover, nucleic acid testing, disinfection of public areas and other methods are needed to prevent human infection and control the COVID-19 epidemic. Community prevention and control workers work mainly in communities. The main work includes providing convenient services to residents, registering mobile personnel, and measuring and monitoring residents’ situations. To address the practical difficulties of community residents during the epidemic, we arranged home quarantine and health observation.

Investigation methods and contents

To investigate the health status and influencing factors of COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control workers during the COVID-19 epidemic, evaluate the health status of epidemic prevention workers and understand the possible influencing factors, this study conducted a questionnaire survey of epidemic prevention workers.

A homemade online questionnaire and nonprobability convenience sampling and snowball sampling methods were employed for the study. The questionnaires were distributed via an online platform (Questionnaire Star) to medical workers, disease control workers, and community prevention and control workers who were directly involved in the workload of the COVID-19 epidemic. The respondents were asked to scan the QR code with their mobile phones to enter the answer page and complete the questions online. At the same time, respondents who had participated in the questionnaire evaluation were encouraged to forward the QR code to their colleagues in epidemic prevention and control work. The research contents of the questionnaire mainly include demographic characteristics, epidemic prevention and control work-related factors, fatigue, sleep quality and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.

Demographic characteristics

Demographic data, including gender, position, current place of residence, education level and working experience, were collected.

Epidemic prevention and control work-related factors

These measures mainly include the use type and replacement of protective equipment during epidemic prevention and control work and daily working hours.

Fatigue

Fatigue was scored according to a 3-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating “mild fatigue”, 2 indicating “moderate fatigue”, and 3 indicating “severe fatigue”. The participants rated their own fatigue. The higher the score is, the more severe the degree of fatigue.

Sleep quality

Research on sleep quality mainly focuses on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Domestic scholar Liu Xianchen et al. (1996) revised the English version of the PSQI, and after extensive testing proved it has good reliability and validity18. The PSQI primarily assesses subjects’ sleep quality over the past 1 month, consisting of 7 components from 18 indicators, including: sleep quality, sleep onset time, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, hypnotic medication use, and daytime dysfunction. Each component is scored 0–3 points. The scores of each component are summed to form a total score (0–21 points). Higher scores indicate worse sleep quality. A PSQI total score > 7 is defined as having sleep quality problems. This study mainly used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) for sleep quality assessment.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms

The presence and severity of PTSD symptoms were assessed using the abbreviated 4-item PCL-5 scale, which corresponds to DSM-5 Criteria B-E for PTSD, with each item rated from 0 (“Not at all”) to 4 (“Extremely”) for a total score range of 0–16. This validated measure demonstrates strong psychometric properties, including excellent internal consistency (α = 0.86–0.92) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.84), high correlations with the full PCL-5 (r = 0.93) and CAPS-5 (r = 0.88), and good discriminant validity (AUC = 0.91 for differentiating PTSD from depression). Using a clinical cutoff score of ≥ 8 (sensitivity = 0.89, specificity = 0.92), the scale provides a time-efficient (2–3 min) assessment suitable for both clinical and research applications with adult populations19,20.

Sample estimation

NCSS PASS 2021was used to estimate the required sample size. In SARS 2003 outbreak in Hongkong, 70% of health care workers had reported fatigue21.Thus the actual proportion (p) was supposed to be 70% with fatigue as the primary outcome. The confidence size was 0.95 and the actual width (i.e. precision) was 0.15*70%, and then the required sample size was 310.

Statistical analysis

Frequencies and percentages and chi-square tests were used to compare rates between groups. Rank data were analysed via the Mann‒Whitney U test and the Kruskal‒Wallis H test. The measurement data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (\(\bar {x}\)± s), and analysis of variance was used for comparisons between groups. Factors with statistically significant differences in single-factor analysis were used as independent variables to perform multifactor ordered logistic regression analysis. P < 0.05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Gannan Healthcare Vocational College on April 4, 2023 (NO:2024001). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Demographic characteristics

As presented in Table 1, the study included 346 prevention and control workers aged 18–68 years (mean age 31.58 ± 8.15). Participants comprised 251 females (72.5%) and predominantly held undergraduate degrees (231, 66.8%). Most resided in urban areas (305, 88.2%). Occupational distribution was: medical workers (232, 67.1%), disease control workers (73, 21.1%), and community prevention workers (41, 11.8%). Regarding work experience, 28.9% had > 11 years and 24.9% had 6–10 years of service.

Factors related to epidemic prevention and control work

The study investigated working conditions among epidemic prevention workers, finding that 63.0% worked 4–8 h daily, with 61.8% primarily using caps combined with medical surgical masks as protective equipment and 37.9% replacing masks every 4–6 h. Notably, 54.0% identified insufficient protection as their greatest work difficulty. These challenging conditions, particularly prolonged work hours and inadequate protective equipment, were found to contribute significantly to workers’ fatigue, insomnia, and increased risk of PTSD.

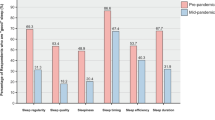

Fatigue and sleep quality

This study examined health conditions such as state of fatigue and sleep quality among prevention and control workers during the COVID-19 prevention and control period. The survey revealed significant fatigue and sleep disturbances among epidemic prevention workers. Over half experienced moderate (42.8%) or severe (8.7%) fatigue, with higher levels among males, bachelor’s-degree holders, and medical staff (doctors/nurses) (P < 0.05). Fatigue was also more severe in workers handling public health emergencies or directly exposed to COVID-19 patients (P < 0.05), though work experience and contact with infected relatives/friends showed no significant effect (P > 0.05). Sleep quality notably declined post-outbreak, with 36.1% reporting reduced sleep and 14.5% experiencing severe deterioration (mean PSQI score: 7.03 ± 2.67). Significant sleep disparities emerged by gender (P = 0.004) and occupation (disease control workers fared worse, P = 0.001), while education and work experience had no impact (P > 0.05). Direct contact with COVID-19 patients (P < 0.001) and involvement in public health emergencies (P = 0.016) further worsened sleep, though infected relatives/friends did not (P > 0.05). See Table 2 for details.

State of fatigue

An ordered logistic regression analysis was conducted using the six factors that had a statistically significant impact on fatigue status in the single-factor analysis as independent variables. The results show that education and occupation are related to fatigued status. Workers with a bachelor’s degree had less fatigue than did those with a graduate degree (OR = 0.391, 95% CI: 0.154 ~ 0.991). Doctors and nurses were more likely to experience fatigue than community prevention and control workers were (OR = 2.599, 95% CI: 1.158 ~ 5.830). Gender, handling public health emergencies, and direct contact with COVID-19 patients did not significantly impact the fatigue status of epidemic prevention and control personnel. The detailed results are shown in Table 3.

Sleep quality

An ordered logistic regression analysis was conducted using the five factors that had a statistically significant impact in the single-factor analysis as independent variables. The likelihood that the sleep quality of workers with direct exposure to COVID-19 patients will be one grade worse than that of workers without direct exposure to COVID-19 patients is 0.318 times greater (Table 4).

PTSD symptoms

The total PTSD score of the workers involved in the prevention and control of the new coronavirus epidemic was 2 (1, 4) points and was right skewed. After normalization, i.e., ln (original score + 1), the total PTSD score of the workers was 0.99 ± 0.70. The difference in PTSD levels between workers who had and had no direct contact with COVID-19 patients was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Workers with different levels of fatigue and different changes in sleep quality before the epidemic had significantly different PTSD scores (both P < 0.001) (Table 5).

Using the three factors that had a statistically significant impact on PTSD in the single-factor analysis as independent variables, multiple linear regression analysis was performed. The results revealed that workers with direct contact with COVID-19 patients had less severe PTSD symptoms (P = 0.002), whereas those with more severe fatigue levels and those with worse sleep quality than they did before the epidemic had more severe PTSD symptoms (both P values < 0.001). See Table 6.

Discussion

This research revealed that during the early stages of the epidemic, epidemic prevention and control workers were generally fatigued. More than 80% of the workers were unable to change their masks in a timely manner, indicating that the workers faced significant work pressure and difficulties in the early stages of the epidemic and that their health conditions were not optimistic. A large-scale survey across the province conducted by multiple social groups in Gansu also revealed that community epidemic prevention and control personnel often work more than normal working hours do, and even a quarter of the personnel who work more than 12 h a day suffer from work-related fatigue. Furthermore, 17% of community epidemic prevention personnel commented that the work intensity was too intense and affected their health22,23. CDC workers also reported severe fatigue problems during the epidemic, with academic qualifications showing a significant positive correlation with fatigue levels (β = 0.32, p < 0.01)24 consistent with our findings. This association may be explained by several interrelated factors: higher-educated personnel likely assumed greater decision-making responsibilities (Role Burden Hypothesis), faced elevated performance expectations (Skill-Expectation Mismatch), managed dual leadership-fieldwork demands, and experienced heightened stress responses due to their greater pandemic-related knowledge (Knowledge-Activation Effect). These observations align with Conservation of Resources theory, suggesting that highly-trained professionals experienced accelerated physical and mental resource depletion during the sustained crisis, particularly when their specialized skills became both professionally critical and personally taxing. The findings underscore the need for targeted psychological support mechanisms for highly-qualified public health workers during prolonged outbreak responses.

Fatigue and burnout are prevalent among healthcare workers, impacting efficiency, medical quality, and safety, as well as causing psychological issues25,26. Long working hours impair cognition and decision-making, potentially increasing medical errors. For example, doctors or nurses may omit critical medical details or misjudge treatment plans, resulting in adverse outcomes for patients27. Donnelly et al.‘s survey in Ontario found fatigue predicts hospital safety issues and threatens health. Medical workers’ intense work and long hours often cause fatigue, leading to medical errors, patient harm, and safety risks26. Studies indicate the COVID-19 epidemic negatively impacted health and social workers’ well-being early on. Fatigue from long hours can cause mood swings and irritability, increasing tension and poor communication with patients, thus affecting patient security and treatment outcomes. Therefore, prolonged fatigue can affect the emotional state and interpersonal relationships of medical workers28,29. Moreover, according to a scientific briefing released by the WHO in March 2020, comprehensive evidence on the early impact of the epidemic shows that fatigue is the main factor inducing suicidal thoughts among health workers30. A longitudinal study among the general population in mainland China revealed that burnout predicts suicidal ideation even in the absence of depressive symptoms31. A survey of ICU workers during the pandemic revealed that 13% of respondents thought about suicide or self-harm. The reason may be the uncertainties associated with COVID-19 and the fear experienced by healthcare practitioners working in response to the pandemic32. Moreover, the risk of cross-infection among medical and nursing workers is high, and the demands for management and control have escalated, resulting in greater pressure. Research by Liang L et al. suggested that the outbreak of the epidemic has raised the standards and requirements for medical forces in special times and confirmed that health practitioners have problems related to sleep quality, anxiety and depression33,34. Frontline workers are vital for epidemic control. Supporting their health is key for sustained epidemic response32. The Australian Medical Association has developed the National Code of Medical Practice Working Hours, Shifts and Scheduling of Hospital Doctors, which aims to change perceptions and attitudes toward the ethics of safe working hours and has been shown to reduce the risk of fatigue among doctors35. In conclusion, fatigue predicts hospital issues and affects health and work environment. Reducing fatigue through better work hours, scheduling, and personnel management improves medical service quality and safety. During epidemics, evidence-based comprehensive approaches are crucial, including clear communication, adequate rest, peer support, stress reduction, resilience building, and mental health promotion36. Moreover, reducing the fatigue and secondary health risks of epidemic prevention personnel is important37.

Previous studies indicate females, especially nurses, face higher fatigue risk, possibly due to dual career and family responsibilities. Males reported more fatigue, but no difference remained after accounting for other factors. This study also revealed that the fatigue level reported by community prevention and control workers and disease prevention and control workers was greater than that reported by medical workers, but after adjusting for other variables, the fatigue level of medical workers was greater. Because this study is a cross-sectional study with a small sample size, especially a small number of male respondents, and does not distinguish the specific categories of workers, it is difficult to conduct an in-depth analysis of these factors. It is suggested that more variables should be included in future studies to describe and compare the possible influencing factors in detail.

The study revealed that during the epidemic, workers, including medics and disease controllers, faced inadequate protection, high work intensity, and manpower and confidence shortages. These workers often work over 9 h daily with heavy workloads, lacking sufficient rest opportunities and a conducive rest environment. These conditions may affect work efficiency and make people less confident in defeating the epidemic. Shah et al.‘s survey in Kenyan hospitals showed fear of infection, staff shortages, inadequate PPE, and work pressure increased health workers’ stress during the epidemic38. The high number of infections among medical workers in the early stages of the outbreak can be attributed to insufficient personal protection, which includes insufficient personal protection awareness, a lack of protection knowledge, short-term protective equipment, long-term exposure, treatment pressure, high work intensity and a lack of adequate rest39. These factors indirectly increase the possibility of infection among medical workers. The heavy reliance on individual protection awareness and knowledge reflects inadequate institutional safety protocols and training systems that should have been established pre-outbreak.

Compared with the sleep quality before the epidemic, 50.6% of the workers reported a decrease in their sleep quality. The sleep quality of workers who have not been in direct contact with COVID-19 patients is worse than that of workers who are in direct contact with COVID-19 patients. This difference may be attributed to the varying levels of awareness and perceived risk of exposure to COVID-19 among these workers. Workers who have direct contact with COVID-19 patients believe that they are less likely to be infected if they have taken appropriate protective measures, resulting in better sleep quality. On the other hand, workers who have not had direct contact with COVID-19 patients worry that such contact might easily lead to infection, thus negatively impacting their sleep quality40.

Workers who had direct contact with COVID-19 patients presented with less severe PTSD symptoms. Shah reported a lower PTSD detection rate of 50.7% among frontline nursing workers38. Workers with direct contact with patients believe that they are less likely to be infected if they have taken appropriate protective measures. However, workers who have not had direct contact with COVID-19 patients are worried that they might easily become infected with COVID-19 if they come into direct contact with patients31. Moreover, workers with more severe levels of fatigue had more severe symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder than before the pandemic. Fatigue is often the result of chronic stress, which can overactivate the brain’s stress response system, increasing the risk of PTSD symptoms41. In addition, fatigue may be due to the accumulation of physical and psychological burdens caused by constant high-intensity work, and this accumulated burden may exacerbate the symptoms of PTSD. On the other hand, fatigued workers may not have enough energy to adopt effective coping strategies to address their traumatic experience, which may aggravate PTSD symptoms. It is very important to provide appropriate psychological support and interventions for workers with severe fatigue42. Compared with pandemic workers, workers with poorer sleep quality were found to have more severe PTSD symptoms. Sleep disturbances are often symptoms of PTSD, and prolonged sleep deprivation can exacerbate other symptoms of PTSD, such as mood swings, memory problems, and difficulty concentrating43.

There are several limitations in this study. First, the cross-sectional design is simple, and the causal relationships between these variables and issues such as fatigue, sleep quality, and PTSD symptoms cannot be determined. Second, in the early stage of the COVID-19 epidemic, all prevention and control workers were in a state of overload, and the use of self-test questionnaires may have resulted in certain diagnostic biases. Although these questionnaires are rapid and effective screening tools, in practice, workers may not be able to complete and evaluate the questionnaire results with sufficient accuracy because of psychological stress, high work intensity and time constraints. Because prevention and control workers usually need to work in a high-intensity work environment for several hours or even days, their fatigued state may also affect the accuracy and completeness of the questionnaire. Working for a long period of time decreases attention and reaction ability, which affects the correct interpretation and judgment of the information in the questionnaire. Finally, due to the COVID-19 epidemic situation, the questionnaire survey was conducted online, the survey method was limited, the compliance of the survey subjects was poor, and the distribution of the basic information of the survey subjects was uneven, which inevitably led to some bias in the research results. Notably, our sample covers epidemic prevention and control workers (including front-line medical care and community personnel) in 14 provinces and 46 cities. To some extent, these findings reflect the physical and mental health status of China’s epidemic prevention and control workers during the early pandemic.

To reduce the possibility of such diagnostic bias, effective measures need to be taken. The first is to provide adequate support and training in the follow-up study to ensure that participants can correctly understand and accurately complete the self-test questionnaire. The second is the reasonable arrangement of working hours and shift systems to avoid excessive fatigue among workers and improve their work efficiency and concentration. Finally, the contents and evaluation criteria of the self-test questionnaire should be reviewed and updated regularly to ensure that the contents are consistent with the actual situation to reduce the possibility of diagnostic bias and ensure the effectiveness and reliability of prevention and control work.

Conclusion

The sleep quality of workers participating in the prevention and control of the COVID-19 epidemic significantly decreased after the outbreak (50.6%), highlighting substantial sleep disturbances among this critical workforce. These findings carry important practical implications: First, the observed correlation between direct patient contact and milder PTSD symptoms suggests that structured exposure protocols and competency-based training may buffer psychological distress. Second, the association of fatigue/sleep decline with severe PTSD symptoms underscores the need for institutional safeguards - including mandatory rest periods, shift rotation systems, and real-time fatigue monitoring - to mitigate long-term mental health consequences. For policy implementation, we recommend that establish longitudinal monitoring of frontline workers’ mental health, linking occupational health data with hospital records to enable early intervention. As pandemic management becomes normalized, these evidence-based measures should be codified into infectious disease preparedness plans to protect responder health during future outbreaks. The findings ultimately call for a paradigm shift - from viewing worker wellbeing as an operational variable to recognizing it as a foundational component of effective epidemic response systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zaveh, G. Z. et al. No 3 the fear of COVID-19 infection one year after business reopening in Iranian society. J. Health Sci. Surveill. Syst. 10 (2022).

Abouzid, M. et al. Influence of COVID-19 on lifestyle behaviors in the middle East and North Africa region: A survey of 5896 individuals. J. Transl. Med. 19 (2021).

Khan, A. H. et al. COVID-19 transmission, vulnerability, persistence and nanotherapy: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 19, 2773–2787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-021-01229-4 (2021).

Fuster, V. & Varieur Turco, J. COVID-19: A lesson in humility and an opportunity for sagacity and hope. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 75, 2625–2626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.008 (2020).

Moynan, D. et al. The role of healthcare staff COVID-19 screening in infection prevention & control. J. Infect. 81, e53–e54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.057 (2020).

Abbasi, M., Yazdanirad, S., Zokaei, M., Falahati, M. & Eyvazzadeh, N. A bayesian network model to predict the role of hospital noise, annoyance, and sensitivity in quality of patient care. BMC Nurs. 21 (2022).

O’Connor, R. C. et al. Mental health and Well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 mental health & wellbeing study. Br. J. Psychiatry. 218, 326–333 (2021).

Azadboni, Z. D. et al. Effect of occupational noise exposure on sleep among workers of textile industry. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 12, LC18–LC21 (2018).

Biswas, A. et al. Emergence of novel coronavirus and COVID-19: whether to stay or die out?? Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 46, 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/1040841X.2020.1739001 (2020).

Yazdanirad, S., Sadeghian, M., Jahadi Naeini, M., Abbasi, M. & Mousavi, S. M. The contribution of hypochondria resulting from Corona virus on the occupational productivity loss through increased job stress and decreased resilience in the central workshop of an oil refinery: A path analysis. Heliyon 7 (2021).

Wong, A. et al. Healing the healer: protecting emergency health care workers’ mental health during COVID-19. Ann. Emerg. Med. 76, 379–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.04.041 (2020).

Aymerich, C. et al. COVID-19 pandemic effects on health worker’s mental health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Psychiatry 65 (2022).

Tracy, D. K. et al. What should be done to support the mental health of healthcare staff treating COVID-19 patients. Br. J. Psychiatry. 217, 537–539. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.109 (2020).

Mercadante, S. et al. Sleep disturbances in patients with advanced Cancer in different palliative care settings. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 50, 786–792 (2015).

El Omrani, O. et al. COVID-19, mental health, and young people’s engagement. J. Adolesc. Health. 72, S18–S19 (2023).

Khammar, A. et al. Effects of bright light shock on sleepiness and adaptation among night workers of a hospital in Iran. Annals Trop. Med. Public. Health. 10, 595–599 (2017).

Xu, X. et al. Evaluation of the mental health status of community frontline medical workers after the normalized management of COVID-19 in sichuan, China. Front. Psychiatry 14 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. The reliability and validity study of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index. Chin. J. Psychiatry. 29, 103–107 (1996).

Zuromski, K. L. et al. Developing an optimal Short-form of the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Depress. Anxiety. 36, 790–800 (2019).

Blevins, C. et al. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J. Trauma. Stress. 28, 489–498 (2015).

Grainne, M. & McAlonan, M. P. Immediate and sustained psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care workers. Can. J. Psychiatry (2007).

Fan, J. et al. Epidemiology of coronavirus disease in Gansu province, china, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26, 1257–1265 (2020).

Lam, L. T., Lam, M. K., Reddy, P. & Wong, P. Efficacy of a workplace intervention program with web-based online and offline modalities for improving workers’ mental health. Front. Psychiatry 13 (2022).

Cui, Q. et al. Research on the influencing factors of fatigue and professional identity among CDC workers in China: an online Cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 12 (2022).

Chou, L. P., Li, C. Y. & Hu, S. C. Job stress and burnout in hospital employees: comparisons of different medical professions in a regional hospital in Taiwan. BMJ Open 4 (2014).

Donnelly, E. A. et al. Fatigue and safety in paramedicine. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 21, 762–765 (2019).

Lu, Y. et al. The mediating role of cumulative fatigue on the association between occupational stress and depressive symptoms: A cross-sectional study among 1327 Chinese primary healthcare professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19, 15477 (2022).

de Salazar, G. et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: systematic review and Meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 275, 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.022 (2020).

Pappa, S. et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Brain. Behav. Immun. 88, 901–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026 (2020).

Witteveen, A. B. et al. COVID-19 and common mental health symptoms in the early phase of the pandemic: an umbrella review of the evidence. PLoS Med. 20 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Prevalence and influencing factors of PTSD symptoms among the general population during the surge period of COVID-19 pandemic in Mainland China. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 87, 151–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2023.10.011 (2024).

Greenberg, N. et al. The Mental Health of Staff Working in Intensive Care During COVID-19. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.03.20208322 (2020).

Jiang, W. X. et al. Implementing a new tuberculosis surveillance system in zhejiang, Jilin and ningxia: improvements, challenges and implications for China’s National health information system. Infect. Dis. Poverty 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-021-00811-w (2021).

Liang, L. et al. Association between burnout and Post-traumatic stress disorder among frontline nurse during COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated mediation analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 33, 1076–1083 (2024).

Bailey, E., Robinson, J. & McGorry, P. Depression and suicide among medical practitioners in Australia. Intern. Med. J. 48, 254–258 (2018).

Lu, Y. et al. Association of working hours and cumulative fatigue among Chinese primary health care professionals. Front Public. Health 11 (2023).

Simon, N. M., Saxe, G. N. & Marmar, C. R. Mental health disorders related to COVID-19-related deaths. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 324, 1493–1494. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.19632 (2020).

Shah, J. et al. Mental health disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey from three major hospitals in Kenya. BMJ Open 1. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050316 (2021).

Maccallum, F. et al. The mental health of Australians bereaved during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent class analysis. Psychol. Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291723003227 (2024).

Bi, Y. et al. A latent class analysis of dissociative PTSD subtype among Chinese adolescents following the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. J. Affect. Disord. 349, 596–603 (2024).

Zhou, Y. G. et al. PTSD: Past, present and future implications for China. Chin. J. Traumatol. Engl. Ed. 24, 187–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjtee.2021.04.011 (2021).

Ouyang, H. et al. The increase of PTSD in Front-line health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and the mediating role of risk perception: A one-year follow-up study. Transl. Psychiatry 12 (2022).

Andhavarapu, S. et al. Post-traumatic stress in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 317 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Development Fund, Macau SAR (Grant 0065/2023/ITP2).

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Development Fund, Macao SAR (FDCT 0065/2023/ITP2, and FDCT 0108/2024/RIB2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YG, Writing - original draft, data curation, resources, investigation, methodology, software and writing – review & editing; YZ, Writing - original draft and data curation; LH, Writing - original draft and software; YW, Writing – review & editing and software; TZ, Writing – review & editing; YX, Supervision, writing – review & editing and investigation; LL, Supervision and writing – review & editing; CW, Supervision, investigation, writing - original draft and methodology; XY, Conceptualization, supervision and writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Gannan Healthcare Vocational College on April 4, 2023 (NO:2024001). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent to participate

All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Y., Zhang, Y., Han, L. et al. Study on fatigue, sleep quality and PTSD symptoms and influencing factors among prevention and control workers during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Sci Rep 15, 35414 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07927-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07927-1