Abstract

To investigate the knowledge, attitudes, and willingness (KAW) of patients with thyroid disease regarding thyroid thermal ablation techniques and explore the factors associated with KAW. This cross-sectional survey was conducted at Yantai Hospital of Shandong Wendeng Orthopaedics & Traumatology and Yantai Affiliated Hospital of Binzhou Medical College between October 2022 and March 2023. This study included 632 patients; 66.14% were female. The mean knowledge, attitude, and willingness scores were 6.03 ± 2.42 (possible range: 0–10), 17.52 ± 2.91 (possible range: 5–25), and 33.02 ± 6.34 (possible range: 8–40), indicating poor knowledge, positive attitudes, and proactive willingness. Multivariable analysis showed that ≥ 51 years old, urban areas, consuming alcohol, medical treatment, and surgical treatment were independently associated with adequate knowledge. The knowledge scores, ≥ 51 years old, females, urban areas, medical treatment, and surgical treatment were independently associated with a positive attitude. Only the attitude scores were independently associated with proactive willingness. Patients with thyroid diseases have poor knowledge, positive attitudes, and proactive practice toward thermal ablation. Sustained efforts are required to increase knowledge about thyroid thermal ablation techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The thyroid diseases commonly encountered in clinical practice include thyroid nodules1,2, hyperthyroidism3, hypothyroidism4,5, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis6, and thyroid cancer7. The prevalence of hyperthyroidism is 0.75–1.2%3,8. Hypothyroidism is observed in 1–2% of the general population, reaching 7% in older adults aged 85–89 years4. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is also a common thyroid condition, observed in 2% of the general population9. Thyroid cancer is the 11th most common cancer, with an estimated 586,202 new cases in 2020 and 43,646 deaths10.

Thyroid nodules represent the most common thyroid disease and are detected in about 60% of adults11. A thyroid nodule is a discrete lesion in the thyroid gland that is radiologically distinct from surrounding normal thyroid tissue1,2. Thyroid nodules are four times more common in female patients than in male patients and occur more frequently with increasing age. Most thyroid nodules are asymptomatic2,11. Palpable nodules are often discovered on physical examination, and nonpalpable nodules are frequently detected incidentally on imaging studies performed for unrelated reasons1,2,12. Symptomatic patients may report symptoms related to hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism, compressive symptoms, or cosmetic concerns1,2,12. Thyroid nodules may be caused by both benign (about 90%) and malignant (about 10%) lesions2. Risk factors for malignancy include a family history of thyroid cancer and a history of radiation therapy. While thyroid nodules may be associated with thyroid dysfunction or local mass effects, the primary clinical concern is to identify and treat lesions that are malignant or at high risk for malignancy1,12.

Ultrasound-guided thermal ablation can be used for benign thyroid nodules causing symptoms or cosmetic concerns as a minimally invasive alternative to surgery or radioactive iodine therapy2,11,12,13. The indications for thermal ablation include mixed, predominantly solid and/or growing nodules determined to be benign after two serial fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies and an evaluation of serum calcitonin levels and cystic or mostly cystic nodules when refractory to initial treatment with percutaneous ethanol injection14. The most commonly used thermal ablation techniques include radiofrequency ablation, laser ablation, and microwave ablation13,15. Radiofrequency ablation and laser ablation are each reported to be well-tolerated and result in reduced nodule volume and improved symptoms13,15. Chinese experts on thyroid ablation have confirmed that microwave ablation of thyroid microcarcinoma is safe and effective based on postoperative pathology16. According to another report in China, compared with RFA and LA, MWA is more suitable for treating greater thyroid nodules, with volume reduction rates ranging from 75 to 90% in follow-up studies up to 12 months17. Radiofrequency ablation may be preferred for benign solid nodules, while laser ablation is reported to be more effective for nodules > 30 mL13. Serious adverse effects or major complications, such as severe pain or recurrent nerve palsy, are reported to be rare and transient13,15. High-intensity focused ultrasound ablation (a needle-free alternative) is a newer procedure with limited evidence for use in the management of thyroid nodules18,19.

Knowledge, attitudes, and practice (KAP) surveys, including variations like knowledge, attitudes, and willingness (KAW) surveys, aim to identify the factors, gaps, misconceptions, and misunderstandings that represent barriers to the performance of a specific subject in a specific population20,21. Previous studies reported variable KAP/KAW regarding thyroid thermal ablation techniques. A study highlighted that the implementation of thyroid thermal ablation techniques was relatively slow in the United States of America22. A survey in Europe showed that only a minority of thyroid practitioners use thermal ablation techniques23. Thermal ablation for thyroid nodules is not a popular option24,25. A study among patients with thyroid nodules reported poor KAW regarding radiofrequency ablation26. A study in Canada by Baerlocher et al.27 showed that none of the patients had ever heard about radiofrequency ablation. The KAP toward radiofrequency has been shown to affect self-management after the procedure28. Some patients also undergo microwave ablation to treat thyroid nodules19, and the present study focused on thermal ablation. Hence, strengthening the KAW toward thermal ablation should help the patients select this effective technique and improve their experience after ablation.

Therefore, this study evaluated the KAW of patients with thyroid diseases regarding thyroid thermal ablation techniques.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

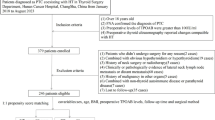

This study collected 656 questionnaires. After excluding those with the same options selected for the whole questionnaire, logical errors, and less than 100 s for answering, 632 questionnaires were included in the analysis. The characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. Most participants were 41–50 years of age (31.33%), female (66.14%), living in urban areas (66.14%), with junior college/undergraduate education and above (63.61%), earning 5000–10,000 (51.11%), with long-term stable jobs (56.33%), not drinking (83.70%), not smoking (79.42%), with medical insurance (98.42%), with an illness history < 3 years (38.29%), and with treatments (76.58%). The diseases included hyperthyroidism (23.42%), Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (17.25%), thyroid nodules (54.91%), thyroid cancer (15.19%), and others (19.15%).

Knowledge

The mean knowledge score was 6.03 ± 2.42 on a maximum of 10 (60.30%), indicating poor knowledge. Higher knowledge scores were observed in older participants (P < 0.001), females (P < 0.001), urban residency (P = 0.001), middle income (P = 0.040), long-term stable job (P = 0.023), not drinking (P = 0.001), not smoking (P < 0.001), with medical insurance (P < 0.001), with thyroid cancer (P < 0.001), and with a history of thermal ablation (P < 0.001) (Table 1). As shown in Supplementary Table S1, the knowledge items with poor knowledge were K3 (55.70%; “Thermal ablation of thyroid nodules is a technique for in situ inactivation of lesions in vivo to achieve local radical cure”), K4 (47.94%; “Thermal ablation techniques include radiofrequency ablation, microwave ablation, and laser ablation”), K6 (9.02%; “The common complications that can be treated with thyroid thermal ablation therapy include bleeding and transient voice changes, but no nerve or parathyroid damage”), K8 (58.23%; “Imaging of the lesion is required before, during and after ablation, where ultrasound imaging is recommended”), K9 (54.91%; “Therapeutic advantages of thermal ablation therapy include minimally invasive, rapid recovery, no impact on thyroid function and no need for lifelong medication”), and K10 (48.89%; “All thyroid diseases can be completely cured by thermal ablation techniques”).

Attitudes

The mean attitude score was 17.52 ± 2.91 on a maximum of 25 (70.08%), indicating favorable attitudes. Higher attitude scores were observed with older age (P < 0.001), males (P < 0.001), living in urban areas (P < 0.001), not drinking (P = 0.001), not smoking (P < 0.001), with medical insurance (P < 0.001), with thyroid cancer (P = 0.001), and with a history of thermal ablation (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Supplementary Table S2 presents the distributions of the attitudes.

Willingness

The mean willingness score was 33.02 ± 6.34 on a maximum of 40 (82.55%), indicating proactive willingness. Higher willingness scores were observed with older age (P = 0.001), males (P < 0.001), urban areas (P < 0.001), not drinking (P < 0.001), not smoking (P < 0.001), with medical insurance (P < 0.001), with other thyroid lesions (P = 0.015), and with a history of thermal ablation (P < 0.001). Supplementary Table S3 presents the distributions of the willingness items.

Correlations

Table 2 shows that the knowledge scores were correlated to the attitude (r = 0.401, P < 0.001) and willingness (r = 0.326, P < 0.001) scores. The attitude scores were correlated to the willingness scores (r = 0.511, P < 0.001).

Multivariable analyses

As shown in Table 3, ≥ 51 years old (vs. ≤ 30 years old, OR = 2.19, 95%CI: 1.13–4.23, P = 0.020), urban areas (OR = 2.01, 95%CI: 1.28–3.16, P = 0.003), consuming alcohol (OR = 0.51, 95%CI: 0.28–0.92, P = 0.025), medical treatment (vs. no treatment, OR = 0.17, 95%CI: 0.08–0.34, P < 0.001), and surgical treatment (vs. no treatment, OR = 0.14, 95%CI: 0.06–0.32, P < 0.001) were independently associated with the adequate knowledge.

As shown in Table 4, the knowledge scores (OR = 1.26, 95%CI: 1.16–1.43, P < 0.001), ≥ 51 years old (vs. ≤ 30 years old, OR = 2.30, 95%CI: 1.13–4.70, P = 0.022), females (OR = 1.90, 95%CI: 1.10–4.70, P = 0.021), urban areas (OR = 1.68, 95%CI: 1.00–2.67, P = 0.048), medical treatment (vs. no treatment, OR = 0.25, 95%CI: 0.10–0.58, P = 0.001), and surgical treatment (vs. no treatment, OR = 0.33, 95%CI: 0.13–0.83, P = 0.018) were independently associated with the positive attitude.

As shown in Table 5, only the attitude scores (OR = 1.50, 95%CI: 1.38–1.64, P < 0.001) were independently associated with proactive willingness.

Discussion

The results showed that patients with thyroid diseases from two Chinese hospitals in the Yantai area have poor knowledge, favorable attitudes, and proactive willingness toward thermal ablation. The results could help design education interventions and identify the points worth more discussions during consultations. Specific knowledge gaps could be identified, allowing interventions to be designed to improve the KAW.

Thermal ablation of thyroid nodules has been shown to be effective and safe2,11,12,13. It is a convenient option that can be performed in the outpatient setting at a relatively low cost and without radiation. Although there is a risk of thyroid/parathyroid function damage after thermal ablation, it is not an absolute risk as with radioactive iodine. Still, previous studies reported a low willingness of American and European thyroid physicians to use thermal ablation for the management of thyroid nodules22,23. Of course, the availability of specialized equipment could influence surgeons’ decisions. In addition, the destruction of the tissues without removing them prevents the possibility of histopathological examinations to determine the exact nature of the nodule. Still, the main indication of thermal ablation is for solid nodules proved benign by two successive FNAs or for cystic nodules refractory to ethanol ablation14. Therefore, according to guidelines14, thermal ablation is used for thyroid nodules with a low risk of malignancy. Still, the accuracy of FNA for thyroid nodules is not 100%29, but in the absence of signs and symptoms of malignant disease, thermal ablation of thyroid nodules is a reasonable option.

A study in Canada showed that none of the 100 patients scheduled for an interventional radiology procedure had ever heard about radiofrequency ablation27. A previous study in Saudi Arabia reported a poor KAW toward radiofrequency ablation of thyroid nodules26. In the present study, Chinese patients showed poor knowledge but favorable attitudes and proactive willingness toward thermal ablation.

The present study showed gaps in specific knowledge items. Specifically, specific knowledge items had poor scores, especially knowledge about the biological mechanisms of thermal ablation, the available thermal ablation methods, the necessity of peri-operative lesion imaging, the advantages of thermal ablation, and which thyroid diseases can be managed using thermal ablation. The knowledge of the complications after thermal ablation scored particularly low (9%). Indeed, only 9% of the patients could correctly identify that the statement “the common complications of thyroid thermal ablation therapy include bleeding and transient voice change but no nerve or parathyroid damage” was incorrect since the most important major post-ablation complication is transient or permanent voice changes due to thermal injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve30. Therefore, educational activities or materials should be designed for this specific patient population to provide or rectify knowledge on thyroid ablation procedures. Future studies should also examine the knowledge of healthcare providers since they act as a primary source of healthcare-related information for patients. Nevertheless, the patients had good attitudes and willingness toward thermal ablation procedures for thyroid diseases, indicating a high level of trust in the judgment of their healthcare providers.

In addition, knowledge was independently associated with attitudes, and attitudes were independently associated with willingness. Therefore, improving knowledge should improve the KAW of the patients. Indeed, according to the KAP theory, knowledge is the basis for practice (or willingness), while attitude is the force driving practice (or willingness)20,21. Therefore, improving knowledge should improve the KAW of the patients. Salah et al.31 showed that an education intervention on thyroid thermal ablation reduced the consultations for post-ablation syndrome. In their study, Xu et al.28 also showed that a KAW intervention improved the patient experience with an ablation procedure. The present study identified younger patients, those with potentially poorer life habits (i.e., drinking), and those who underwent medical or surgical treatment. There is a possibility that the physicians did not consider the option of thermal ablation in some patients and did not discuss the option with the patients. In addition, some included participants had hyperthyroidism and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis; such patients are not eligible for thermal ablation, and the option was probably not discussed at all.

This study had limitations. It was performed at only two hospitals in China, limiting the generalizability of the conclusions. The questionnaire was designed by local investigators and might be biased based on local guidelines and practice, also limiting generalizability. No previous data on the KAW of Chinese patients with thyroid diseases toward thermal ablation were available, preventing comparisons. Nevertheless, the present study could serve as a baseline to examine the impact of future education interventions. KAP surveys (and variations) are also subject to the social desirability bias, in which the participants can answer what they should do instead of what they really do32,33. Finally, an information bias is possible regarding the attitude and practice scores. Indeed, the patients with thyroid diseases were not specially informed about thyroid thermal ablation therapy during the study, but there were no limits based on their background to that information. About 30% of the patients had experience with thermal ablation therapy, and such patients probably already had knowledge about thermal ablation therapy. Many thyroid diseases do not require thermal ablation therapy for treatment, and it is possible that such patients would never seek information about thermal ablation therapy. Hence, it is possible that their first information about ablation therapy came from the questionnaire itself. Nevertheless, they did not know whether the knowledge statements were true or false, and they had to answer to the best of their knowledge. Although the participants knew that some knowledge statements were false (since they were asked to tell whether the statements were true or not), many patients without experience of thermal ablation procedures were exposed for the first time to the knowledge statements, and they could consider many of them to be true while they were not. Hence, they could come to know, falsely, that these procedures were advantageous, minimally invasive, and required limited anesthesia to be performed, with no mention of the rare though most commonly cited risks of surgery (permanent nerve damage and severe hypocalcemia). Hence, positive attitudes and willingness could be expected, as patients might be naturally inclined, based on positive presentation, to see ablation procedures as less harmful and advantageous with respect to surgery. Therefore, there is a risk of misrepresenting patient’s feelings if a potential lack of information about procedure risk is not considered. It will have to be carefully considered and controlled for in future studies.

In conclusion, patients with thyroid diseases in the Yantai area have poor knowledge, favorable attitudes, and proactive willingness toward thermal ablation. Specific gaps in knowledge could be identified. Interventions should be designed to inform the patients of the treatment options for thyroid diseases to improve the KAW of the patients toward thermal ablation. Sustained efforts are required to increase knowledge about thyroid thermal ablation techniques.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional survey was conducted at Shandong Wendeng Osteopathic Hospital and Yantai Affiliated Hospital of Binzhou Medical University between October 2022 and March 2023 and included patients with thyroid diseases attending outpatient clinics. The study was approved by the Shandong Wendeng Osteopathic Hospital Ethics Committees and Yantai Affiliated Hospital of Binzhou Medical University Ethics Committees. Informed consent was obtained from the study subjects.

The inclusion criteria were (1) 18–75 years old, (2) with thyroid disease, including hyperthyroidism, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, thyroid nodules, and thyroid cancer, and (3) voluntarily participated in this study.

Procedures

The questionnaire was designed with reference to the Chinese Expert Consensus on the Thermal Ablation of Benign Thyroid Nodules, Microscopic Carcinoma, and Metastatic Lymph Nodes in the Neck (2018 version)34. The first draft was revised by one senior expert. Fifty patients were randomly selected for reliability testing, showing Cronbach’s α = 0.8563.

The final questionnaire contained four dimensions: demographic characteristics (age, gender, education, place of residence, type of work, monthly household income, alcohol consumption, smoking, type of medical insurance, type of thyroid disease, duration of illness, and type of therapy for thyroid diseases), knowledge dimension, attitude dimension, and willingness dimension. The knowledge dimension consisted of 10 items, with 1 point for a correct answer and 0 points for a wrong or unclear answer, ranging from 0 to 10 points. The attitude dimension consisted of five items using a 5-point Likert scale, with positive attitude questions being forward assigned, from strongly agree to strongly disagree scored 5 points to 1 point, and negative attitude questions (items A2 and A5) being reverse assigned, with scores ranging from 5 to 25 points. The willingness dimension contained eight items, also using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from always (5 points) to never (1 point), with a score range of 8–40 points. Adequate knowledge, positive attitudes, and proactive willingness were defined using a threshold of ≥ 70% for each score35.

Questionnaire distribution and quality control

The questionnaire was imported into the Sojump online questionnaire platform (https://www.wjx.cn/app/survey.aspx), and a valid link was generated. The questionnaires were distributed to the study participants through a live code scan on WeChat. The questionnaire was set to ensure that only one person could fill in the questionnaire with a given IP address. The uniformly trained research assistants instructed the participants on the requirements and instructions for completing the questionnaire before distribution, and they were available to answer patients’ questions. The questionnaires were automatically numbered and anonymous and stated the requirements for completing the questionnaire, the purpose of the information collected, and the confidentiality of the information. Questionnaires with missing items could not be submitted. The questionnaires with the same options selected for the whole questionnaire, logical errors, and less than 100 s for answering were excluded.

Statistical analysis

Stata 17.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were first tested for normality. Continuous data with a normal distribution were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and Student’s t-test was used to compare the two groups. For continuous variables with three or more groups that conformed to a normal distribution with homogeneous variance, ANOVA was used for comparisons among multiple groups; otherwise, the Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance was used. Categorical variables are expressed as frequency (percentage). Multivariable regression was used to analyze the association between demographic information and adequate knowledge, positive attitude, and proactive willingness. Variables with P < 0.05 in the univariable analyses were included in the multivariable analysis. Two-sided P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- KAW:

-

Knowledge, attitudes, and willingness

- FNA:

-

Fine needle aspiration

- KAP:

-

Knowledge, attitudes, and practice

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Haugen, B. R. et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: The American Thyroid Association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 26, 1–133 (2016).

Durante, C. et al. The diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules: A review. JAMA 319, 914–924 (2018).

Ross, D. S. et al. 2016 American Thyroid Association guidelines for diagnosis and management of hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid 26, 1343–1421 (2016).

Taylor, P. N. et al. Global epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14, 301–316 (2018).

Chaker, L., Bianco, A. C., Jonklaas, J. & Peeters, R. P. Hypothyroidism. Lancet 390, 1550–1562 (2017).

Caturegli, P., De Remigis, A. & Rose, N. R. Hashimoto thyroiditis: Clinical and diagnostic criteria. Autoimmun. Rev. 13, 391–397 (2014).

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Thyroid Carcinoma. Version 1.2023. Fort Washington: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2023.

Garmendia, M. A., Santos, P. S., Guillen-Grima, F. & Galofre, J. C. The incidence and prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in Europe: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, 923–931 (2014).

Ahmed, R., Al-Shaikh, S. & Akhtar, M. Hashimoto thyroiditis: A century later. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 19, 181–186 (2012).

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Grani, G., Sponziello, M., Pecce, V., Ramundo, V. & Durante, C. Contemporary thyroid nodule evaluation and management. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105, 2869–2883 (2020).

Gharib, H. et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of endocrinology, and associazione medici endocrinologi medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules–2016 update. Endocr. Pract. 22, 622–639 (2016).

Cho, S. J., Baek, J. H., Chung, S. R., Choi, Y. J. & Lee, J. H. Long-term results of thermal ablation of benign thyroid nodules: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul). 35, 339–350 (2020).

Papini, E., Monpeyssen, H., Frasoldati, A. & Hegedus, L. 2020 European Thyroid Association clinical practice guideline for the use of image-guided ablation in benign thyroid nodules. Eur. Thyroid. J. 9, 172–185 (2020).

Chen, F., Tian, G., Kong, D., Zhong, L. & Jiang, T. Radiofrequency ablation for treatment of benign thyroid nodules: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes. Medicine (Baltimore) 95, e4659 (2016).

Ding, M. et al. Pathology confirmation of the efficacy and safety of microwave ablation in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Front Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 929651 (2022).

Liu, L. H. et al. Factors related to the absorption rate of benign thyroid nodules after image-guided microwave ablation: A 3-year follow-up. Int. J. Hyperthermia. 39, 8–14 (2022).

Lang, B. H. & Wu, A. L. H. High intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation of benign thyroid nodules—a systematic review. J. Ther. Ultrasound. 5, 11 (2017).

Cui, T., Jin, C., Jiao, D., Teng, D. & Sui, G. Safety and efficacy of microwave ablation for benign thyroid nodules and papillary thyroid microcarcinomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Radiol. 118, 58–64 (2019).

Andrade, C., Menon, V., Ameen, S. & Kumar, P. S. Designing and conducting knowledge, attitude, and practice surveys in psychiatry: practical guidance. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 42, 478–481 (2020).

World Health Organization. Advocacy, communication and social mobilization for TB control: A guide to developing knowledge, attitude and practice surveys. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596176_eng.pdf. Accessed November 22, 20222008.

Kuo, J. H., McManus, C. & Lee, J. A. Analyzing the adoption of radiofrequency ablation of thyroid nodules using the diffusion of innovations theory: Understanding where we are in the United States?. Ultrasonography. 41, 25–33 (2022).

Hegedus, L., Frasoldati, A., Negro, R. & Papini, E. European Thyroid Association survey on use of minimally invasive techniques for thyroid nodules. Eur. Thyroid J. 9, 194–204 (2020).

Merdad, M. A contemporary look at thyroid nodule management. What every Saudi physician and surgeon should know. Saudi Med. J. 41, 123–127 (2020).

Barajas, M. S., Fraga, T. C., Acevedo, M. A. & Cabrera, R. G. Radiofrequency ablation: A review of current knowledge, therapeutic perspectives, complications, and contraindications. IJBSBE. 4, 56–58 (2018).

Albaqawi, R., Alreschidi, M., Almuhelb, A., Aladel, F. & Alrashidi, I. Awareness, knowledge and attitudes regarding radiofrequency ablation as treatment option for thyroid nodules in Saudi Arabia. Med. Sci. 24, 2439–2444 (2020).

Baerlocher, M. O. et al. Awareness of interventional radiology among patients referred to the interventional radiology department: A survey of patients in a large Canadian community hospital. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 18, 633–637 (2007).

Xu, W. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and behavior in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing radiofrequency catheter ablation. J. Interv. Card Electrophysiol. 28, 199–207 (2010).

Lan, L. et al. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of thyroid cancer with ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration and core-needle biopsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11, 44 (2020).

Kim, J. H. et al. 2017 thyroid radiofrequency ablation guideline: Korean society of thyroid radiology. Korean J. Radiol. 19, 632–655 (2018).

Salah, M. A., Tawfeek, S. O. & Ahmed, H. O. Radiofrequency ablation therapy: Effect of educational nursing guidelines on knowledge and post ablation syndrome for patients withhepatocellular carcinoma. Am. J. Sci. 8, 719–729 (2012).

Bergen, N. & Labonte, R. Everything is perfect, and we have no problems: Detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 30, 783–792 (2020).

Latkin, C. A., Edwards, C., Davey-Rothwell, M. A. & Tobin, K. E. The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addict. Behav. 73, 133–136 (2017).

Thyroid tumor ablation Technology Expert Group of Chinese Medical Doctor Association, Thyroid Cancer Professional Committee of Chinese Anti-Cancer Association, Ultrasonic Intervention Professional Committee of Interventional Physicians Branch of Chinese Medical Doctor Association. Expert consensus on the treatment of benign thyroid nodule, microcarcinoma and cervical metastatic lymph node by thermal ablation (2018 edition). Chin J oncol. 27, 768–773 (2018).

Lee, F. & Suryohusodo, A. A. Knowledge, attitude, and practice assessment toward COVID-19 among communities in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia: A cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 10, 957630 (2022).

Funding

This study was funded by a Study on the molecular immune mechanism of ultrasound-guided microwave implantation ablation for thyroid cancer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ying Liu, Lihong Liu, Weiwei Zhao and Jinling Wang carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. Shoujun Yu and Shurong Wang performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. Jinke Li, Lu Zhou and Liang Hao participated in acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was carried out after the protocol was approved by the Shandong Wendeng Osteopathic Hospital Ethics Committees and Yantai Affiliated Hospital of Binzhou Medical University Ethics Committees (F-KY-0022-200220325-01). I confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines. All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Liu, L., Wang, J. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and willingness of patients with thyroid diseases toward thyroid thermal ablation techniques. Sci Rep 15, 24811 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08044-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08044-9