Abstract

The aim of this study was to assess the clinical performance of a monoshade universal resin composite as posterior restoration. Twenty adult patients having at least two carious lesions related to posterior teeth were selected. Each patient was provided with a monoshade resin composite (Omnichroma) and polyshade nanohybrid resin composite (Tetric® N-Ceram) for class I or II restorations. The performance of these restorations was assessed at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months according to the modified United States Public Health Service (USPHS) criteria. Statistical analysis was carried out employing the Friedmann test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, with a significance level of p = 0.05. None of the restorations exhibited any clinical conditions warranting replacement. The monoshade universal group revealed prevalence of (Bravo) scores concerning the anatomic form, surface texture and post-operative sensitivity through the follow-up period (P = 0.317). For color match and color stability, the polyshade group revealed a statistically significantly higher incidence of (Alpha) scores after 9 and 12 months (P = 0.025). After 12-months of follow-up, the monoshade universal resin composite demonstrated satisfactory clinical performance. It can serve as a viable substitute for polyshade nanohybrid composite where chair side time is an essential concern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Replicating every natural characteristic of a tooth artificially is not always simple, as dentin and enamel differ in thickness, structure, composition, and, most notably, optical properties. Using a polyshade (polychromatic) or three-dimensional layering approach is a successful way to create direct resin composite (RC) restorations that look as natural as possible. With this method, the dentist can adjust the opacity and translucency of each layer to blend seamlessly with the neighboring teeth. Although the layering process requires more time and skill from the operator, it produces satisfactory outcomes in color matching1,2.

The goal of reducing the duration of restoration procedures and structuring color matching prompted dental manufacturers to compete in creating a universal RC (monoshade) that could be matched to a broad spectrum of universal tints. As the desire for enhanced esthetics and functionality continues to rise, the direction of RCs is shifting towards the integration of all-in-one technology. Clinicians are actively seeking materials that are user-friendly, time-efficient, and capable of meeting patients’ heightened expectations. Although no single material possesses all the necessary qualities, monoshade structurally colored universal RC may be paving the way for a future that offers sustainability, in which clinicians and patients no longer need to concern themselves with shade selection or replacing the fillings due to the failure of color matching3,4.

Tokuyama Dental America introduced the Smart Chromatic Technology of Omnichroma® as the first manufactured monoshade universal RC, which enables the material to achieve extensive color-matching capabilities by producing a red-to-yellow structural color, similar to that of natural teeth. This chameleon effect is achieved by managing the size of the filler particles. The chameleon effect refers to a cosmetic characteristic that allows restorative material to blend with and mimic the color of its environment relying on the fact that resin composite (RC) materials displaying this optical property significantly reduce aesthetic mishaps5,6.

Even though a monoshade universal resin composite is considered a suitable option for numerous restorations, it might not be appropriate in every instance, and conventional shade-matching techniques may still be required. It’s crucial to assess the potential limitations of this material in each unique situation, as monoshade universal RCs’ shade-matching capabilities may not be as accurate as those of conventional composite materials7,8.

Clinically based studies are constantly introduced to put hands on various factors that cannot be tested in in-vitro research. The interaction of mastication, saliva, change of pH due to various foods and beverages, and temperature changes on dental restorations may alter the protocols dentists follow while applying multiple restorative materials. Since there have been only a few in-vivo studies on single-shade universal RC, more research is needed to evaluate the color matching and clinical efficacy of this type of RC9,10.

Thus, the aim of the research was to compare, at baseline and at the three, six, nine, and twelve-month follow-ups, the color matching of the monoshade composite Omnichroma® and its clinical effectiveness, in comparison with the polyshade nanohybrid RC, Tetric‑N‑Ceram®, in Class I and II carious lesions. The null supposed hypothesis suggested that there were no significant discrepancies in the clinical effectiveness of monoshade universal RC restorations compared to conventional polyshade nanohybrid RC restorations for class I and II restorations over 12 months. The current study is dedicated to addressing the following question: Does the clinical effectiveness of monoshade universal RC as a posterior restoration surpass that of the conventional polyshade nanohybrid RC, as evaluated using the modified USPHS criteria?

Methods

Sample size calculation

The calculation for the sample size was derived from previous studies on the clinical success rate of composite restorations, which indicated a 93% success rate at 12 months11. Earlier studies on posterior tooth restorations, utilizing a significance level of 0.05, a power of 80%, and an equivalency margin of 20%, determined a required sample size of 18 restorations. To account for potential dropouts, we targeted a sample of 20 restorations per group, resulting in a total of 40 restorations, given the use of the split-mouth approach.

Protocol registration

This study underwent registration on www.clinicaltrials.gov, using the protocol’s distinct identification code NCT05500547 on 15/08/2022. This experimental protocol and all investigations comprising human subjects were approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Dentistry, Minia University, bearing code number 420 (Ref. no. 27/06/2020) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design

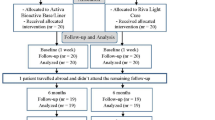

The study design adhered to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement12. In the present study, a double-blinded clinical trial was conducted, where both patients and examining operators were unaware of the randomization procedure for the inserted restorations. A split-mouth design was implemented, and online software (www.sealedenvelope.com) was employed to determine two parallel groups with a 1:1 allocation ratio. Each patient received two RC restorations where single shade universal RC (Omnichroma) was employed on one side (Group I) and multi-shade RC (Tetric® N-Ceram) was employed on the other side (Group II) randomly.

Patient selection

The present study included patients who visited the Conservative Department Clinic for dental care. Patient selection continued until reaching 20 patients that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The obtained written informed consent from each patient clearly outlined the procedure before any procedure was conducted to guarantee their awareness of the study’s purpose. The study included patients whose ages ranged from 20 to 40 years. These patients were suffering from carious lesions, either occlusal or proximal, in collateral posterior teeth. These lesions were clinically identified, and a radiograph was used to evaluate their extent. “As identified by the radiographic examination, only cavities with caries extending no more than half the thickness of the coronal dentin were included. Heavy smokers, patients with deleterious parafunctional habits, bruxism, traumatic occlusion, or those on prescribed antibiotics within six months prior to inclusion in the study, as well as patients taking analgesics that could potentially affect pain perception, those with obvious wear facets on the occlusal surface, those undergoing orthodontic treatment, or those with temporomandibular joint issues, were excluded from the trial. Additionally, pregnant women and medically compromised patients were not considered eligible for the study.

The included patients were required to have satisfactory oral hygiene, with gingival tissues in a healthy condition, no recession or alveolar bone loss around the teeth, and no orofacial pain or sudden pain. Other criteria were applied, such as having opposing natural teeth free of restorations, a normal and complete occlusion, and a good response to electric pulp testing conducted using the Pulp Tester DY 310 with a threshold of 0–39 (Denjoy Dental Co., Ltd., Changsha, China). The pulp vitality testing was applied to the tooth that required a restorative procedure and its contralateral counterpart.

Randomization and blinding

Using the website www.random.org, a split-mouth design was implemented, and a random list was generated to assign participants to two groups. Sequentially, each patient selected a number from 1 to 20 based on the previously generated random lists. Throughout the study, both the assessing operator and the participating patients remained unaware of their assigned treatment. However, blinding the operator was not possible due to the nature of the shade selection procedure that was required13.

Clinical procedure

Before any procedure was performed, shade selection was completed prior to dehydration, which could adversely affect the color value. Each participant’s teeth were first checked for cleanliness and cleaned if needed. The shade evaluation was conducted during the time frame from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. The unit lamps were turned off to ensure uniform ambient lighting and make use of natural daylight. To prevent strong contrasts and possible result distortion, a neutrally colored napkin was used to cover the patient’s clothing. Before the session, the participants were asked not to apply any external makeup that could alter the operator’s ability to distinguish different shades. The shade determination was then carried out visually using the VITA Classical A1-D4 shade guide (VITA Zahnfabrik)14. Anesthesia was administered to each patient utilizing 1.8 mL of 2% lidocaine hydrochloride combined with phenylephrine (1:2500) (SS White 100, SS White, Petrópolis, Brazil). Rubber dam isolation was achieved with Ivoclar Vivadent’s OptraDam® Plus, and cavity preparation was performed utilizing a #330 high-speed carbide bur (FG, Dentsply Midwest®, Germany). Subsequently, the remaining carious tissue was eliminated using tungsten carbide burs (Komet, Brasseler GmbH Co. KG) at a low speed, in addition to sharp excavators (mailfaire 57/58, Switzerland). The cavity preparation was limited to managing decay while preserving sound tooth structure using the selective caries removal technique. Afterward, any irregularities in the enamel walls of the cavity were smoothed utilizing yellow-coded stones (Komet, Germany).

For Class II cavities, an appropriate sectional matrix and wooden wedges were used for matrixing. In the current study, a 36% phosphoric acid gel was applied to selectively etch the enamel for 30 s, followed by rinsing and air drying for 5 s using a gentle, moisture- and oil-free airflow. Afterward, a single drop of adhesive was applied and scrubbed onto the surface for 20 s. The area was then gently air-dried with an oil-free airflow for 3–5 s, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, a 20-second light curing process was performed with direct occlusal contact. Bluephase N wireless light cure with wavelength ranging from 385 to 515 nm and light intensity of 1100 mW/cm2 was used with zero contact to the occlusal surface of the tooth to be restored in the bonding procedure and curing of each resin composite increment. Complete charging of the light-cured device and daily testing before the use of light cure was performed to make sure that the output light intensity is the same each day using the Bluephase meter II (Bluephase Style, Ivoclar-Vivadent, Schaan/Liechtenstein).

A single-shade universal RC (Omnichroma) and a multi-shade nanohybrid RC (Tetric® N-Ceram) were used (Table 1). RC application was performed strictly following the instructions provided by the respective manufacturers. RC was packed into the prepared cavities using an incremental approach. Each increment was applied in oblique layers, up to 4 layers, in accordance with the cavity size, with a 2 mm maximum thickness per increment. After each increment, 20 s of light curing were applied. During the same appointment, and after the removal of the isolating rubber dam, the restorations underwent meticulous finishing and contouring with fine-grit diamond finishing stones (Komet, Brasseler GmbH Co. KG) at low speed and with ample water. Additionally, articulating paper (Bausch, Nashua, NH, USA) was employed to check for premature contacts in centric and eccentric occlusion, sequentially using 100 µM and 40 µM15. The restorations were promptly polished utilizing EVE DIACOMP Plus OccluFlex-impregnated rubber cups and impregnated brushes (Optishine, Kerr Switzerland) with a water coolant. To achieve a smooth surface, Sof-Lex discs (3 M ESPE, Germany) were used in the prescribed sequence of coarse, medium, fine, and superfine, accompanied by a water coolant, to finish the buccal and lingual embrasures in Class II cavities. The first (the black disc) was used only when there was bulky buccal or lingual restorative material, to reduce the time required for finishing and polishing Fig. 1.

Clinical evaluation

All restorations were handled by one experienced operator from the research team. However, for the clinical assessment of the restorations performed, two independent and experienced dentists who were not part of the restorative procedure evaluated the restorations at 0, 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months utilizing the modified USPHS criteria. During the follow-up period, restorations were assessed for color match and color stability, anatomic form, retention, surface texture, marginal discoloration, marginal adaptation, contact surface, secondary caries, and patient acceptability. They used a mirror, a probe, and a magnifying loupe with a magnification power of 3.5x (Ziess, Germany). To ensure optimal visibility, the magnifying loupe was equipped with a powerful light source (Ziess Eyemag Light II LED illumination system, Ziess, Germany).

After completing the final finishing and polishing, a photographic evaluation was performed to assess the achieved shade matching in both groups. A DSLR camera (Canon 700D) with a Sigma 105 mm f/2.8 EX DG OS HSM macro lens, a close-up Speedlight ring flash (Yongnuo, Shenzhen Yongnuo Photographic Equipment Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), contractors, retractors (cheek and lip), and mirrors were used. At each follow-up appointment, clinical intraoral photographs and radiographs were captured, and the USPHS parameters were recorded utilizing a standardized case report for each patient during the evaluation procedures. Additionally, each restoration was evaluated using a compressed air stream directed toward the restoration (2–3 cm away) to assess postoperative sensitivity, with proper isolation of neighboring teeth. This process lasted for three seconds, followed by gently running a probe across the restored tooth surface16. To determine their clinical acceptability, a scoring system was employed, with Alfa and Bravo indicating exceptional and clinically sufficient findings, Charlie for clinically unacceptable findings that require replacement, and Delta representing clinical failures such as retention loss, significant marginal weaknesses, or discoloration necessitating immediate replacement or repair (Table 2).

Statistical analysis

The percentages and frequencies were employed to present the qualitative data. A comparison of the clinical evaluation scores among the two groups was conducted employing the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The temporal changes within every group were investigated utilizing Friedman’s test. The numerical data underwent assessment for normality by investigating the data distribution and conducting normality tests, including the Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. All color change data exhibited a non-normal (non-parametric) distribution. The data were presented using measures such as mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and range values. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the two groups in terms of non-parametric data. The statistical analysis was conducted utilizing IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0, developed by IBM Corp in Armonk, NY. A significance level of P ≤ 0.05 was established, indicating the threshold for statistical significance.

Result

Prior to performing the current study, a pre-calibration process was conducted with 10 patients who were not part of the study, ensuring a reliability of 90%. The examiners demonstrated a noteworthy level of agreement, ranging from substantial to nearly ideal (Table 3). Of the twenty patients treated, 13 were males (65%), while 7 were females (35%). Demographic analysis for the distribution of teeth and the classification of cases displayed no statistically significant difference among the two groups (P = 0.750, 0.655), respectively (Table 4). A 100% recall rate was achieved during the 12-month recall period, Fig. 2. Tables 5 and 6 present the clinical evaluation findings conducted during the 12-month monitoring period according to the modified USPHS. 100% of the restorations were found to lie among the Alpha and Bravo scores, with no statistically significant difference among the two groups, except at nine and 12 months for color stability and color match. In these cases, 15 restorations from the Omnichroma group received Bravo scores (75%), which showed a statistically significant difference (P = 0.025) in comparison to the Tetric N group. No significant differences were identified between baseline and 12 months (P > 0.05), given that all restorations in both groups achieved (Alpha) scores for retention, recurrent caries, marginal discoloration, and marginal adaptation. Meanwhile, there were insignificant differences in the surface texture and anatomic form between the tested groups at baseline, one month, three month, and six months. At both the nine and 12-month follow-up periods, 5% of patients showed (Bravo) scores in the Omnichroma group, with no statistically significant differences marked between both groups (P = 0.317). Concerning postoperative sensitivity, after three, six, nine, and 12 months, 5 − 10% of patients showed (Bravo) scores in both groups with no statistically significant differences (P = 0.317, 0.157) observed among both groups Figure (3, 4, 5, 6).

Based on the reliability test results, both inter-observer and intra-observer reliability demonstrate excellent consistency across all evaluation parameters. Inter-observer reliability shows particularly strong agreement, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.867 to 0.987, indicating exceptional internal consistency among different raters. The corresponding ICC values (0.752–0.899) further confirm substantial to almost perfect agreement between observers. Similarly, intra-observer reliability exhibits high consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.787 to 0.985, suggesting strong repeatability within individual raters’ assessments. ICC values for intra-observer reliability (0.723–0.952) indicate good to excellent consistency in repeated measurements by the same observer. All reliability measures achieved statistical significance (p < 0.001), providing robust evidence that the assessment methodology is highly reliable and reproducible. Notably, parameters such as “Color match and color stability” and “Patient complaint” show the strongest consistency across both reliability measures, while “Retention scores” and “Post-operative sensitivity” demonstrate relatively lower, though still significantly strong, reliability coefficients. These comprehensive reliability results validate the assessment tool as a dependable instrument for evaluating dental restorations across multiple clinical parameters.

Discussion

The main objective of esthetic dentistry is to attain visual characteristics that closely mimic the appearance of natural enamel and dentin, ensuring that dental restorations blend seamlessly with their surroundings and remain virtually undetectable. Furthermore, it replicates not only just the visual attributes but also the physical attributes of enamel and dentin, ensuring their functional suitability2. The current study aimed to compare the clinical effectiveness and color matching of monoshade universal RC versus polyshade RC in the treatment of class I and II carious lesions over a one-year follow-up period.

Studying the clinical performance of monoshade universal RC with structural coloring in posterior teeth provides valuable knowledge for clinicians, enabling them to advocate for dental materials that mimic and harmonize with natural tooth shades. This simplifies shade selection and reproduction, ensures patient satisfaction, and enhances aesthetic dental procedures. Limited research has been conducted on the clinical effectiveness of Omnichroma, and currently, there is insufficient in vivo evidence regarding its efficacy. Consequently, this clinical trial was conducted to assess and contrast the clinical efficacy of Omnichroma with Tetric-N-Ceram in permanent posterior teeth using USPHS criteria. These criteria allow for valid comparisons among studies with different observation periods, and modified versions of these criteria are still widely utilized to assess different aspects of restorations17,18.

The hypothesis was accepted as the follow-up data collected after one year indicated that both materials performed similarly. The majority of scores for the restorative materials used in this study fell within the acceptable range of Alpha to Bravo, indicating satisfactory outcomes.

The current findings concerning the color stability and color match revealed no significant difference between the two RC materials tested throughout the whole recall period. This outcome can be ascribed to the smart chromatic technology of the resin composites, which reflects the colors encompassing the spectrum from red to yellow, which occur in all teeth. This innovative technology relies on the utilization of fillers (uniform supra-nano round and spherical fillers composed of silica and zirconia particles), which are hypothesized to generate structural color spanning from red to yellow when light interacts with them. The surrounding tooth color is combined with these colors to create an unparalleled color matching19.

Omnichroma has a remarkable ability to optically mimic the surrounding structure without any pigments integrated into the material. This optical behavior is achieved through the nanofillers’ ability to selectively interact with specific light wave frequencies, resulting in the precise reflection of a distinct wavelength within the natural tooth color spectrum20. To achieve this optical ability, the RC filler must contain only uniform, spherical particles of precise dimension21.

These results were confirmed by Ebaya et al., who stated that monoshade universal resin composites demonstrate acceptable surface smoothness and effectively match the color of various tooth shades19. Consequently, the composite, after curing, integrates with the adjacent tooth structure. These results are in accordance with Sensi et al., who proved that Omnichroma exhibited minimal discoloration upon exposure to simulated aging22.

Following the initial 9-month assessment duration, some structurally colored universal resin composite restorations in a monoshade exhibited a shift to the Bravo score regarding color stability but remained clinically acceptable. This finding aligns with the results reported by de Abreu et al. and Iyer et al.23,24, who specified that the monoshade RC exhibits inferior color matching compared to polyshade RC, which may limit its clinical applicability in cases with superior aesthetic demands. Moreover, Ebaya et al. and Forabosco et al.19,25 verified that the aging technique had an adverse impact on the surface characteristics color stability of universal RCs, suggesting that water absorption affects the mechanical characteristics of composites, resulting in hydrolytic decomposition. In addition, it can potentially lead to micro-fractures at the filler/resin matrix interface and cause superficial stress because of significant temperature gradient fluctuations. These factors can ultimately impact the surface roughness and increase the composite’s susceptibility to stain absorption.

The patient’s primary goal in assessing the quality of aesthetic treatment is to achieve accurate color matching among the dental restoration and the natural dental structure. The recent development of restorative systems incorporating multiple shades and varying translucency levels—high, medium, and low-value enamel shade RCs—stems from the pursuit of more realistic and natural-looking restorations26. Omnichroma®, a material capable of achieving a wide range of color matching, was selected for its smart chromatic technology, which controls its optical properties. Its arrangement of filler particles corresponds to the wavelengths of visible light, which helps limit color distortion and minimize shade variation over time by reducing photochemical deterioration27,28. The mechanical and physical characteristics of a nanohybrid RC called Tetric N-Ceram are influenced by the presence of nanofillers, including nanomers and nanoclusters, which act as nanomodifiers29,30.

The selection of additional criteria for assessing the clinical efficacy of the RCs, such as retention, postoperative sensitivity, secondary caries, contact surface, marginal discoloration, and marginal adaptation, was based on their association with polymerization shrinkage31.

Omnichroma and TetricNCeram performed similarly over 12 months with no statistically significant difference for the assessed clinical criteria except for post-operative sensitivity. After three, six, nine, and twelve months, 5 − 10%, for groups I and II, respectively, patients showed (Bravo) scores in both groups with no statistically significant difference observed between both groups.

In terms of retention, the results of the current study were confirmed by the research carried out by Zulekha et al.1, who demonstrated that the similar amount of filler content may explain the comparable results for both types of RCs, which reduces polymerization shrinkage, using the same clinical technique, isolation protocol, bonding agent, and exposure to the similar oral environment.

Based on a meta-analysis, it was found that conventional RC restorations exhibited superior marginal adaptation compared to RC restorations with new and modified monomers after a 12-month follow-up. However, for more extended follow-up periods, no considerable variations were noted among the two types of restorations24.

Conflicting outcomes were presented by Bajabaa et al.32, where Omnichroma exhibited greater microleakage than Tetric‑N‑Ceram. This could be attributed to the inclusion of TEGDMA in the Omnichroma resin matrix, which has a lower molecular weight than Bis‑GMA and UDMA in Tetric‑N‑Ceram. Consequently, this significantly exacerbates microleakage and polymerization shrinkage. Microleakage can lead to stain penetration, water sorption, and eventually discoloration.

The patient complaints in the current study showed that 5–10% of their complaints were related to postoperative sensitivity (group I and II, respectively), which decreased over the follow-up period. Kruly et al. and Rajnekar et al.31,33 reported that postoperative sensitivity can arise due to the resin composites’ polymerization shrinkage stress. Excessive stress during polymerization poses a challenge to the bonded interface, as it can lead to the formation of cracks in the dentin on the pulpal floor. Despite implementing alterations in tooth surface treatments, making changes to polymerization methods, and adopting incremental placement techniques for composite restorations, postoperative sensitivity remains a challenging and unresolved problem encountered by patients.

The polishability and polish retention may result from the specific alignment of the filler particles. Kim et al.34,35 found that, after finishing, Omnichroma exhibited a notably smoother surface than Tetric N-Ceram. Adhering to the guidelines provided by the manufacturer, the exceptional polishability of Omnichroma can be attributed to the use of uniform spherical fillers at the nano scale, along with consistent spacing between the filler particles. In contrast, Khairy et al.36 conducted a study that yielded comparable results concerning the surface roughness of the Nano-fill composite (Omnichroma) in comparison to the Nano-hybrid composite. The findings suggested that the roughness of Omnichroma tends to be higher than that observed in Nano-hybrid composites. Modifying the filler’s chemical composition, type, and quantity can impact the level of wear experienced by restorations. Decreasing the filler content enhances the polishability but diminishes the overall resistance to wear37.

In this study, patient acceptability was assessed, with patient satisfaction recognized as a crucial factor contributing to the success of dental treatment. The results showed that all patients demonstrated a satisfactory level of acceptability, as indicated by the Alpha score. This is supported by Nagi et al., who reported a high level of patient satisfaction with the monoshade universal RC38.

One of the primary constraints of this research is that a 12-month period might be insufficient to identify substantial changes. Therefore, prolonged clinical assessment studies may provide a more valuable evaluation of the clinical performance of monoshade universal RCs.

Further in-vivo investigations are required to explore the impact of food and beverage stains on the long-term shade-matching permanence of Omnichroma dental resin restorative composite. Additionally, assessing the influence of pH variations and the effects of acids on the microstructure of Omnichroma composite is crucial, as it allows for correlation with its mechanical and esthetic properties. Further evaluation of contemporary monoshade universal resin composites and the possible differences between them may be useful for assessing the clinical success of these materials.

Conclusion

Based on the results of this clinical trial; Omnichroma demonstrated comparable performance to Tetric-N-Ceram and can be utilized as a substitute for polyshade nanohybrid composite when chair side time is an essential concern. Class-I and II carious lesions are successfully treated with monoshade composites, which exhibit good color matching and clinical performance.

Data availability

The corresponding author can provide the datasets utilized and/or examined in the present study upon a reasonable request.

References

Zulekha, Vinay, C. et al. Clinical performance of one shade universal composite resin and nanohybrid composite resin as full coronal esthetic restorations in primary maxillary incisors: A randomized controlled trial. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 40 (2), 159–164 (2022).

Priya, P., Nimisha, C. S., Renu, B., Niral, K. & Aishwarya, J. Evaluation of clinical performance and colour match of single and multiple shade composites in Class-I restorations: A randomised clinical study. JCDR 18 (5), ZC06–ZC11 (2024).

Hashem, D. et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of calcium silicate vs. glass ionomer cement indirect pulp capping and restoration assessment criteria: A randomised controlled clinical trial—2-year results. Clin. Oral Invest. 23, 1931–1939 (2019).

Mohamed, M. A. et al. Shade-Matching capacity of omnichroma in anterior restorations. J. Dent. Sci. 5 (1), 000247 (2020).

Dina, A. E. & Can OMNICHROMA Revoke Other Restor. Composite? E D J. ;68(4):3701–3716. (2022).

Bayne, S. C. & Schmalz, G. Reprinting the classic Article on USPHS evaluation methods for measuring the clinical research performance of restorative materials. Clin. Oral Investig. 9 (4), 209–214 (2005).

Kitasako, Y., Sadr, A., Burrow, M. F. & Tagami, J. Thirty-six month clinical evaluation of a highly filled flowable composite for direct posterior restorations. Aust Dent. J. 61 (3), 366–373 (2016).

Lempel, E. et al. Retrospective study of direct composite restorations according to the USPHS criteria. Fogorv. Sz. 105 (2), 47–52 (2012).

Schlichting, L. H. et al. Ultrathin CAD-CAM glass-ceramic and composite resin occlusal veneers for the treatment of severe dental erosion: an up to 3-year randomized clinical trial. J. Prosthet. Dent. 128 (2), 158e1–158e12 (2022).

Opdam, N. J. M. et al. Clinical studies in restorative dentistry: new directions and new demands. Dent. Mater. 34 (1), 1–12 (2018).

Gruythuysen, R., van Strijp, G. & Wu, M. K. Long-term survival of indirect pulp treatment performed in primary and permanent teeth with clinically diagnosed deep carious lesions. J. Endod. 36 (9), 1490–1493 (2010).

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., Moher, D. & Group, C. O. N. S. O. R. T. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. PLoS Med. 24 (3), e1000251 (2010).

Torres, C., Augusto, M. G., Mathias-Santamaria, I. F., Di Nicoló, R. & Borges, A. B. Pure Ormocer vs methacrylate composites on posterior teeth: A Double-blinded randomized clinical trial. Oper. Dent. 1 (4), 359–367 (2020).

Abu-Hossin, S. et al. Comparison of digital and visual tooth shade selection. Clin. Experimental Dent. Res. 9 (2), 368–374 (2023).

Elkady, M., Abdelhakim, S. & Riad, M. The clinical performance of dental resin composite repeatedly preheated: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Dent. 144, 104940 (2024).

Grover, V. et al. ISP good clinical practice recommendations for the management of dentin hypersensitivity. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 26 (4), 307–333 (2022).

Pfister, J. L. et al. Randomized clinical Split-Mouth study on partial ceramic crowns luted with a Self-adhesive resin cement with or without selective enamel etching: Long-Term results after 15 years. J. Adhes. Dent. 6, 25 (2023).

Cavalheiro, C. P. et al. Choosing the criteria for clinical evaluation of composite restorations: an analysis of impact on reliability and treatment decision. Bras. Odontopediatria Clín Integr. 20, e5088 (2020).

Maha, M. E., Ashraf, I. A., Huda, A. E. & Salah, H. M. Color stability and surface roughness of ormocer– versus methacrylate–based single shade composite in anterior restoration. BMC Oral Health. 27 (1), 430 (2022).

Korkut, B., Ünal, T. & Can, E. Two-year retrospective evaluation of monoshade universal composites in direct veneer and diastema closure restorations. J. Esthetic Restor. Dentistry. 35 (3), 525–537 (2023).

Favoreto, M. W., de Oliveira de Miranda, A., Matos, T. P., de Castro, A. D. S., de Abreu Cardoso, M., Beatriz, J., … Loguercio, A. D. Color evaluation of a one-shade used for restoration of non-carious cervical lesions: an equivalence randomized clinical trial. BMC Oral Health, 2024;24(1), 1–14.

Sensi, L., Winkler, C. & Geraldeli, S. Accelerated aging effects on color stability of potentially color-adjusting resin-based composites. Oper. Dent. 1 (2), 188–196 (2021).

João, L. B., de Abreu, C. S. S., Ernesto, B. B. J. & Ronaldo, H. Analysis of the color matching of universal resin composites in anterior restorations. J. Esthet Restor. Dent. 33, 269–276 (2021).

Rubinya, S. I., Vinti, R. B., Peter, Y. & Joseph, D. Color match using instrumental and visual methods for single, group, and multi-shade composite resins. J. Esthet Restor. Dent. 33, 394–400 (2021).

Forabosco, E. et al. Color Match of Single-Shade Versus Multi-Shade Resin Composites: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis (Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry, 2025).

Schmeling, M., Meyer-Filho, A., Andrada, M. A. C. & Baratieri L. N. Chromatic influence of value resin composites. Oper. Dent. 35 (1), 44–49 (2010).

Korkut, B., Hacıali, Ç., Tüter Bayraktar, E. & Yanıkoğlu, F. The assessment of color adjustment potentials for monoshade universal composites. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 30 (1), 20220189 (2023).

Graf, N. & Ilie, N. Long-term mechanical stability and light transmission characteristics of one shade resin-based composites. J. Dent. 116, 103915 (2022).

Parth, V. D. et al. Clinical evaluation of Cention–N and nano hybrid composite resin as a restoration of non-carious cervical lesion. J. Dent. Spec. 7 (1), 3–5 (2019).

Shanitha, S. & Gautam, R. Recent advances in newer generation composites: an overview. WJARR 14 (02), 100–103 (2022).

Paula de Castro, K. et al. Meta-analysis of the clinical behavior of posterior direct resin restorations: low polymerization shrinkage resin in comparison to methacrylate composite resin. PLoS One. 21 (2), e0191942 (2018).

Sahar, B. et al. Microleakage evaluation in class V cavities restored with five different resin composites: in vitro dye leakage study. Clin. Cosmet. Investig Dent. 27, 13 (2021).

Rutuja, R. et al. Clinical efficacy of two different desensitizers in reducing postoperative sensitivity following composite restorations. Cureus 15 (6), e25977 (2022).

Haesong, K., Juhyun, L., Haeni, K. & Howon, P. Surface roughness and cariogenic microbial adhesion after Polishing of smart chromatic Technology-based composite resin. J. Korean Acad. Pediatr. Dent. 50 (1), 65–74 (2023).

Şahin, H. C. & Korkut, B. Color adjustment of single-shade composites following staining, repolishing, and bleaching procedures. BMC Oral Health. 25 (1), 248 (2025).

Adham, A. K., Radwa, I. E. & Nadia, Z. Effect of finishing/polishing techniques on surface roughness of three different resin composite materials: A laboratory study. MJD 9 (3), 82–88 (2022).

Syed, N. H., Iffat, N., Toby, T. & Manish, R. Clinical performance of resin-modified glass ionomer cement, flowable composite, and polyacid-modified resin composite in noncarious cervical lesions: One-year follow-up. J. Conserv. Dent. 21 (5), 510–515 (2018).

Shaymaa, M. N. & Lamiaa, M. M. Color match clinical evaluation and patients’ acceptability for a single shade universal resin composite in class III and V anterior restorations. JIDMR 15, 230–236 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Khaled Keraa for his great contribution to the statistical analysis of this study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was planned by M Riad. M Riad and RS Anwar contributed to the conception and design and drafted the manuscript. The literature review was prepared by M Riad and RS Anwar and the experiments were performed by RS Anwar. data inference by YF Hussein and RS Anwar. All authors conducted a thorough review of the manuscript to ensure its intellectual content was critically revised. All authors have thoroughly reviewed and endorsed the final manuscript, providing their final approval and accepting responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current study’s protocol has been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov under the unique identification number NCT05500547 on 15/08/2022. The ethical guidelines of the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry, Minia University. (Ref. no. 420) were adhered to in conducting all procedures involving human participants before they participated in the study, every patient provided written consent, demonstrating their understanding and awareness of the study’s nature and their voluntary involvement in it.

Consent for publication

To ensure that patients were fully informed about their participation in this study and understood its nature, we obtained written consent from each patient that clearly outlined the procedure, recall periods, and the utilization of intraoral photos for scientific purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anwar, R.S., Hussein, Y.F. & Riad, M. The clinical performance of monoshade resin composite as posterior restoration: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Sci Rep 15, 25279 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08857-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08857-8