Abstract

This work studies the flow properties of a penta hybrid nanofluid and gyrotactic microorganism influence along an elongating surface. This study uniquely investigates the interaction of gyrotactic microorganisms with a penta-hybrid nanofluid (PHNF), marking a significant advancement over previous ternary hybrid nanofluid (THNF) models by introducing enhanced thermal and biological coupling through the inclusion of five distinct nanoparticles. The numerical solution is performed using MATLAB for the ODE equations. Convective boundary conditions are used to examine the rates of heat and mass transport, and the model incorporates external factors like magnetic fields and porous media. The Buongiorno model also takes into account the impact of Brownian motion and thermophoretic forces on the volumetric fraction of the nanoparticles. The results show that an increase in the magnetic parameter (M) and porous media factor (K) leads to a decrease in both the velocity profiles x and y velocity profile. An increase in K, however, increases the temperature, concentration, and microorganism profiles. On the other hand, an increase in the ratio parameter (α) increases the velocity profile in the y-direction but decreases the temperature, concentration, and microorganism profiles. Besides, larger radiation and Brownian motion parameters both lead to increased temperature profile, while the increased Brownian parameter leads to the decrease in the concentration profile. Surprisingly, PHNF is more effective than ternary hybrid nanofluid (THNF) and has superior thermal and mass transport characteristics. The optimisation of nanofluid and microbe applications, such as heat exchangers and biotechnological processes, where effective heat and mass transmission is essential, may benefit from these discoveries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanofluids are created by suspending ultra-fine particles in a base fluid, thus improving the thermal properties of the fluid. The exceptional property of nanofluids, thanks to the highly thermally conductive nanoparticles, as pointed out by Choi and Eastman1, means phenomenal improvement in heat transfer efficiency. The fluids have been a subject of immense interest due to their promise in improving the heat transfer for a range of applications2. Acharya et al.3 feel that the nanolayer generated in a NF contributes more to heat transmission compared to the nanoparticles’ size. When exposed to flowing circumstances, nanofluids also exhibit a range of rheological behaviours. The fluid dynamics and, therefore, the heat transfer behaviour of the fluid are impacted by variations in viscosity and stresses from shear distributions4. Along with this, the properties of nanofluids can be exactly tailored by adjusting parameters such as the concentration of nanoparticles, their size, and material composition, which leaves further scope for the improvement of Performance of HF5. Hussain et al.6 explored how chemical reactions influence the flow of nanofluids within a solar duct system used for cooling applications. Additionally, researchers have progressively recognized that the thermal performance of base fluids can be significantly enhanced by incorporating a combination of different types of nanoparticles, rather than relying on a single type. According to many investigations, this hybrid nanofluid has better thermal flow characteristics7,8,9. Hybrid nanofluids result from blending a mixture of various types of nanoparticles with a base fluid, which enhances its thermal conductance beyond the value of single nanoparticle nanofluids. Each type of nanoparticle possesses special characteristics that contribute towards changing the thermal conductivity and rheology of the fluid, hence enhancing the overall performance in heat transfer10. The interaction among the nanoparticles leads to altered flow patterns and HF modes that, subsequently, increase convective HF coefficients and reduce thermal resistance to provide higher rate of HF11. The ability to have flexibility in changing the concentration and composition of nanoparticles in nanofluids brings in the possibility of engineering thermal properties to the rigorous specifications of heat transfer applications. To cite an example, Ismail et al.12 studied the effectiveness of a lubricated HNF containing SiO2 and TiO2 nanoparticles in polyvinyl ether as the host fluid. Waqas et al.13 examined heat transfer via hybrid nanofluid flow under thermal radiation conditions, and they concluded that temperature was improved as nanoparticles’ concentration was raised. Similar to this, Rehman et al.14 performed computer simulations for nonlinear time-dependent mixed convective NF flow under novel mass flux circumstances and found that an increase in the concentration of nanoparticles enhanced the heat distribution while decreasing the flow velocity. Another class of nanofluids are ternary hybrid nanofluid. Much research has been conducted in this field15,16,17.

Penta hybrid nanofluid is a high-performance fluid that consists of a base fluid (e.g., water or oil) and one or more than one nanoparticle. Five various types of nanoparticles are present in a penta hybrid nanofluid, typically consisting of metals, metal oxides, or carbon nanoparticles. This novel blend is employed to enhance the thermal conductivity, viscosity, and stability of the fluid in such a way as to demonstrate enhanced heat transfer properties than unary composites or binary nanofluids. The use of penta hybrid nanofluids has the principal advantage of increased heat transfer due to the co-operation of different nanoparticles to achieve optimal overall fluid performance under all thermal and mechanical conditions18.

Thermal radiation is a heat transfer process where energy is emitted away in the form of electromagnetic waves, primarily in the infrared region of the spectrum. In contrast to conduction and convection, thermal radiation does not require a material medium to travel and can travel effectively through a vacuum. This feature makes it an extremely significant mode of energy transfer in outer space and situations with no physical medium19. Mishra et al.20 explored the behavior of couple-stress nanofluids with internal heat generation and the effect of activation energy in their work. Moreover, Mishra et al.21 also performed another study on the transient bio-convective flow of nanofluids along a rotating vertical plane affected by chemical reactions and microbial growth. References22,23 are other studies conducted in this field. When there is thermal radiation, fluid dynamic properties and material behavior change as the thermal gradients in the fluid and around the structure alter24. Thermal radiation further directly heats up the body and boundaries of the fluid with resultant high rates of heat transfer. The synergistic effect of radiation and fluid flow can significantly modify temperature profiles, affecting processes such as forced convection, free convection, and radiative heat transfer25. References26,27 are other studies conducted in this field. Oluwaseun et al.28 considered unsteady squeezing flow and thermal transport behaviors of nanofluids on rotating, radially stretching disks and concluded that the drag force decreased with an increase in nanoparticle concentration. Mishra and Mondal29 also discussed magnetohydrodynamic flow of nanofluids with motile microorganisms over translating surfaces vertically, emphasizing the effect of both Coriolis and Lorentz forces together. Mandal et al.30 provided a theoretical model for unsteady MHD flow of nanofluids over a bi-directional stretching sheet embedded with gyrotactic microorganisms. In addition, Rehman et al.31 suggested a multiphysics model of magnetohydrodynamic flow over a porous surface with thermal radiation and Darcy-Forchheimer effects on fluid behavior. Other significant contributions to the study of MHD flows are references32,33,34,35,36,37,38.

Microorganisms are living microscopic organisms that are invisible to the naked eye and require the help of microscopes to detect them. The movement of fluids at the microscale involving microorganisms—especially in water-based settings—represents a highly intricate interplay between heat transfer mechanisms and the biological behaviors of these organisms. This dynamic interaction plays a crucial role in influencing both natural ecosystems and human-designed systems in significant ways39. Different microorganisms, such as planktonic bacteria and algae, engage with fluid environments in different ways. They may be carried passively by the flow, actively swim in the fluid medium, or exist in larger collective forms such as biofilms40. Such dynamic interaction, in turn, can strongly affect fluid properties by changing parameters like the intensity of turbulence, mixing efficiency, and thermal transport behavior. Microbial activity in fluids can also have a profound effect on altering heat distribution because microorganisms react to and influence thermal gradients that enhance or suppress convective heat transfer processes41. Microorganism metabolic activities can also create localized temperature gradients that create micro-heating or cooling zones around the organisms. Microorganism presence can indirectly influence heat transfer by inducing biofouling or biofilm generation on submerged surfaces, resulting in thermal conductivity, surface roughness, and overall system efficiency alteration, especially in applications such as heat exchangers and marine equipment42. Construction of a richer comprehension of interaction between microorganisms and fluid is of cardinal significance in the administration of aquatic ecosystems, enhancing predictive environmental models, and optimizing thermal management solutions currently employed in fields of environmental science, biotechnology, and oceanic engineering. The impact of microorganisms on Casson’s flow of fluid over surfaces was investigated by Lone et al.43, who discovered that the application of the Casson factor enhances the flow’s thermal characteristics. Rehman et al.44 examined the bio-convective influence on magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) fluid flow over Darcy-Forchheimer permeable media with the inclusion of activation energy contribution in their model. Some relevant studies examining related problems are cited in the references45,46,47,48,49.

Brownian motion fluid flow enhances the complexity of the heat transfer process, especially suspended tiny particles in a fluid medium system50. Thermophoresis is a colloidal suspension effect, and it is known as the movement of particles in a directed direction by temperature gradients. Thermophoretic forces propel the suspended particles to the colder side when a thermal gradient is subjected to the fluid51,52. The interactions between thermophoresis, Brownian motion, and fluid flow play important roles in the impact on heat transfer, particularly in colloidal suspension or nanofluid systems53. Thermal energy-driven Brownian motion promotes random particle movement inside the fluid, which enables their dispersion and mixing54. This migration, in addition to influencing the particle distribution, also thermal conductivity of the fluid particle mixture, therefore heat transfer efficiency55,56. Thermophoresis, in particular, leads to the change in particle concentration in the vicinity of hot or cold surfaces, therefore the local heat transfer rates by concentration or dilution of particles in such regions57. Thermophoresis and Brownian motion work together to describe the thermal performance of devices such as heat exchangers58,59. The impact of Brownian motion and thermophoresis on mass and heat transfer during fluid flow over a perpendicular surface was investigated by Suma et al.60. Higher Darcy factor values improved heat transfer along velocity distribution, according to research done by Rehman et al.61 on the flow of lubricated nanofluid over a stretched sheet with the Darcy-Forchheimer medium effect. An examination of unsteady bio-convective nanofluid flow along the impacts of activation energy, microorganisms, and Darcy-Forchheimer was also carried out by Rehman et al.62.

Kumar et al.63 discussed the implementation of machine learning and nanofluids for enhanced heat transport performance in thermal systems. The authors are inspired by the growing demand for the use of nanoparticles in the enhancement of energy transport in systems like cooling systems, energy production systems, and biomedical devices. They proposed a new tri-hybrid model of a fluid consisting of AA7072, SWCNT, and MWCNT particles in water suspension. The study will analyze the heat transport behavior of the ternary mixture under the effect of magnetohydrodynamic flow with different temperatures. The significance of this study lies in the ability of this work to be applied in real-life applications like biosensors, medical heating devices, and high-efficiency energy systems. Kumar et al.64 included magnetic field effect, Joule heating, thermal radiation, and the impact of the activation energy in a Maxwell–Sutterby–Casson fluid over a stretching sheet. The effect of thermophoresis, gyrotactic microorganisms, and Brownian motion has also been considered in an effort to model bio-convective behavior. The results indicated how fluid and heat properties are extremely susceptible to thermophoresis parameters, magnetic intensity, and bioconvection parameters and provided an interesting observation for future thermal applications. Kumar et al.65 also investigated the thermal enhancement of ternary hybrid nanofluids in a rotating disc and its potential in rotating systems heat transfer optimization and energy storage and cooling systems. The study focused on the effect of magnetic and radiative heat transfer on temperature and concentration and velocity profiles. The use of ternary hybrid nanofluids was also found to contribute to high thermal performance rather than simpler blends. Kumar et al.66 examined the thermal performance of ternary hybrid nanofluids due to their growing importance in improving heat and mass exchange. They formulated a computational simulation of an unsteady ternary-hybrid nanofluid film flowing over a thin film with thermal radiation, inclined magnetic field, and viscous dissipation. The study highlighted the enhanced thermal performance of the SWCNT-Al₂O₃-MWCNT/H₂O composite over simpler composite nanofluids.

This study deals with the investigation of three-dimensional penta-hybrid nanofluid flow behavior of a viscous nanofluid in motion along a Elongating sheet. Fluid flow is simulated as constant, or steady, in terms of time, and incompressible, meaning density variations are neglected. Special attention is given to the imposition of convective boundary conditions in order that a complete analysis of the thermal and mass transfer characteristics associated with flow over a stretching surface can be achieved. The analysis also considers the influence of fluid flow through a porous medium, as well as the influence of an externally applied magnetic field, in order to better simulate real-life conditions. Furthermore, the work also takes into account thermal radiation phenomena and internal heat generation or absorption within the system. For nanoparticle motion observation in the base fluid, Buongiorno model is adopted, which accounts for Brownian diffusion and thermophoretic transport mechanisms in terms of nanoparticle volume fraction. In addition, the suspension of the gyrotactic microorganisms in the nanofluid is considered, adding a further aspect of biological complexity to the dynamics of the system and influencing the generated flow and thermal structures.

Problem description

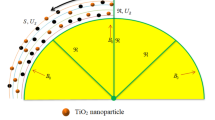

Investigate the flow dynamics of a viscous penta-hybrid nanofluid as it flows along the stretching surface in the plane z = 0 and perpendicular to the x- and y-directions. It is supposed that the components of flow \((u,v,w)\) are along corresponding axes, as shown in Fig. 1. Convective boundary conditions are applied to analyze the mass and heat transport. The following conditions govern the geometry of the problem:

Also, the following are assumed: The surface moves in the x-direction at a speed uw(x) = ax, with a being a positive constant, and in the y-direction at a speed vw(y) = by, with b being a positive constant as well. An applied magnetic field of amplitude B0 exists along the z-axis. The influence of Brownian motion and thermophoretic forces on the nanoparticles’ concentration, as explained by the Buongiorno model, is also considered in the research. Thermal radiation and internal heat generation will also be included.

The assumptions are summarized as follows:

-

The surface stretches in the direction of the x-axis and the y-axis with a velocity described as uw(x) = ax and vw(y) = by, in which a, b > 0.

-

A constant magnetic field with a strength B0 in the direction of the positive z-axis.

-

The thermophoretic effect and the effect of the Brownian motion on the volume fraction of nanoparticles are considered by applying the Buongiorno model.

-

Heat generation within the fluid and thermal radiation are taken into account in thermal analysis.

-

Also, the model makes use of gyrotactic microorganisms in a base fluid, introducing a biological element into the fluid dynamics.

Assumptions of steady, laminar, and incompressible flow in this work remain valid to portray typical operating conditions in industrial and engineering systems for a broad range. In polymer extrusion applications, film cooling and biomedical microfluidic devices, the flow indeed occurs at the low to moderate Reynolds numbers where laminar behavior will prevail and turbulent contributions are immaterial. Steady-state assumption will be appropriate for constant and controlled operation with no sudden temporal variations. The incompressibility assumption will be appropriate for liquid-based fluids such as penta-hybrid composites where the variation in density with respect to temperature or pressure is immaterial. These assumptions not only simplify the mathematical formulation but also align with the physical behavior observed in relevant real-world systems.

To accurately portray the nanoparticle transport mechanisms in the penta-hybrid nanofluid, in this present analysis the Buongiorno model has been employed, which has been known to account for two major slip mechanisms, namely the Brownian motion and thermophoresis. The Brownian motion describes the random diffusion of nanoparticles owing to collisions with the carrier fluid molecules, while thermophoresis describes the particle movement owing to the temperature gradient. In this model, the equation for the nanoparticle volume fraction is enhanced in a manner to include the Brownian diffusion and thermophoretic diffusion terms with additional nonlinearity in the concentration and energy equations. These are represented by the Brownian diffusion coefficient (DB) and thermophoretic diffusion coefficient (DT) and added in the concentration and temperature field equations. Introduction of these terms generates coupled thermal and concentration gradients with considerable effect on the heat and mass transfer properties in the nanofluid. The Buongiorno model is consequently most suitable for this current analysis since it yields physically more accurate descriptions of particle transport in penta-hybrid nanofluids than the simpler thermal equilibrium and no-slip based models. This is particularly suitable in high-thermal-gradient regimes and complex interaction between different types of nanoparticles like in penta-hybrid systems. The model also facilitates simpler coupling with convective and bio-convective flow arrangements, which form the basis of this current study.

The present three-dimensional geometric configuration with bidirectional stretching of a surface with convective boundary conditions and the application of a transverse magnetic field offers a closer representation of real engineering systems than a typical two-dimensional or single-directional configuration. The configuration facilitates a study of multidirectional transport behavior in polymer extrusion, coating flows, and biofilm dynamics. Incorporation of convective heat and mass transfer conditions into the model broadens the scope of the model’s application to real systems. The configuration also facilitates a study of the effect of stretching along two directions on nanoparticle distribution, thermal fields, and gyrotactic microorganisms and brings in new information on coupled fluid-thermal-biologic interactions in hybrid nanofluids.

The vector form of the Asay equations is as follows (Eqs. 1–5)67,68,69:

In which we have (Eq. 6):

The expanded basic equations related to the problem are as follows (Eqs. 7–12)67,68,69:

We also have (Eq. 13):

The boundary conditions (Eq. 14) are as follows:

The applied boundary conditions reflect realistic physical mechanisms occurring near a stretching surface in a PHNF environment. The surface is stretched in the x and y-directions by the velocities u = uw(x) = ax and v = vw(y) = by, with zero normal velocity (w = 0), for a model impermeable surface. There is convective heat transfer into the fluid, represented by the condition \(- {k_{phnf}}\frac{{\partial T}}{{\partial z}}={h_f}({T_f} - T)\), for finite thermal conductivity at the surface. Similarly, the solute mass transfer is represented by \(- {D_B}\frac{{\partial C}}{{\partial z}}={h_m}({C_f} - C)\), allowing for gradients in the solute in the vicinity of the wall. Bioconvective microorganism transport is represented by the bioconvective flux \(- {D_m}\frac{{\partial N}}{{\partial z}}={h_n}({N_f} - N)\), representing the transport of microorganisms from the wall to the fluid due to microorganism concentration gradients. In the far-field, as z → ∞, conditions represent the assumptions that the velocity components, temperature (T), solute concentration (C), and density of motile microorganisms (N) vanish to ambient conditions (i.e., zero), such that physical effects due to the presence of the surface decay away from the wall.

We have the following conversions (Eq. 15):

The equations after substitution of transformations become as follows (Eqs. 16–20):

Equations 16 and 17 are related to the velocity in the x and y directions. Equation 18 is related to the dimensionless temperature profile and dimensionless Eqs. 19 and 20 are related to the concentration and microorganism, respectively. Also, the transformed boundary (Eq. 21) conditions are as follows (Table 1):

The coefficients included in the relationships are defined as follows (Eq. 22):

Table 2 contains the formulas for the ternary hybrid nanofluid used for parameter calculations.

The formulae for the PHNF used to calculate parameters are shown in Table 3.

Also, the parameters are as follows:

\(Pr = \frac{{\mu_{f} (C_{p} )_{f} }}{{k_{f} }}\) | define the Prandtl number |

\(Sc = \frac{{v_{f} }}{{D_{B} }}\) | define the Schmidt number |

\(Nt = \frac{{(\rho C_{p} )_{p} D_{T} (T_{f} - T_{\infty } )}}{{(\rho C_{p} )_{f} v_{f} T_{\infty } }}\) | define the Thermophoresis parameter |

\(Nb = \frac{{(\rho C_{p} )_{p} D_{B} (C_{f} - C_{\infty } )}}{{(\rho C_{p} )_{f} v_{f} }}\) | define the Brownian motion parameter |

\(K = \frac{{\nu_{f} }}{ak}\) | define the Porous media parameter |

\(Bi_{N} = \frac{{h_{n} }}{{D_{m} }}\sqrt {\frac{{v_{f} }}{a}}\) | define the Microorganisms Biot number |

\(M = \frac{{\sigma B_{0}^{2} }}{{a\rho_{f} }}\) | define the Magnetic parameter |

\(L_{b} = \frac{{v_{f} }}{{D_{m} }}\) | define the number of Lewis |

\(Q = \frac{{Q^{*} }}{{a(\rho C_{p} )_{f} }}\) | define the Heat source parameter |

\(\alpha = \frac{b}{a}\) | define the Ratio parameter |

\(Bi_{T} = \frac{{h_{f} }}{{k_{f} }}\sqrt {\frac{{v_{f} }}{a}}\) | define the Thermal Biot number |

\(Bi_{C} = \frac{{h_{m} }}{{D_{B} }}\sqrt {\frac{{v_{f} }}{a}}\) | define the Concentration Biot number |

\(Pe = \frac{{b^{*} W_{0} }}{{D_{m} }}\) | define the number of Peclet |

The physical quantities of the problem are defined as follows (Eqs. 23–25):

Solution

In this paper, the MATLAB bvp4c function, based on shooting method to solve the boundary value problem, is employed. The shooting method is extremely capable to solve the nonlinear ordinary differential equations (ODEs) because it simplifies the solving process considerably. One benefit of this method is that there is the provision to select the error tolerance and accordingly there is room for flexibility in precision control of solution. The method offers an economical way of obtaining the solution with less computational effort. To implement this approach, we first convert the system of higher-order ODEs to a system of first-order ODEs, thus simplifying the problem for numerical methods. This is done in order to implement the shooting method effectively and obtain accurate results. The flowchart for the numerical solution method in MATLAB is shown in Fig. 2.

We transform the set of higher-order ordinary differential equations into first-order ordinary differential equations using Eq. 29.

.

Using Eq. 29, the dimensionless equations and boundary conditions become as follows (Eqs. 30–35):

Figure 3 shows the grid independence of the numerical solution using MATLAB BVP4C.

Figures 4.a and 4.b show the validation of the present model by comparing the values of and with the results from Refs67] and [68. for different values of the α. The close match between the present results and those in the literature confirms the accuracy and consistency of the current numerical model.

Result

Figure 5 shows the effect of magnetic parameter (M) on velocity profile, f‘(η), of two different nanofluids: penta hybrid nanofluid (PHNF) and ternary hybrid nanofluid (THNF). An increase in magnetic parameter reduces the velocity because of magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) effect where magnetic field increases the fluid flow resistance. The magnetic field gets coupled with the moving charged particles in the fluid to create a Lorentz force against motion and hence decreasing the velocity on the x-axis. Moreover, as M is increased, the viscosity of fluid increases due to the fact that the magnetic field causes higher friction between the surface and the fluid, which in turn increases resistance. PHNF, which has a larger quantity of nanoparticles compared to THNF, presents greater reduction of velocity owing to the larger nanoparticle concentration, hence more viscous effect. Consequently, there exists higher resistance towards flow, raising the deceleration effect caused by the existence of the magnetic field. As such, the larger the proportion of nanoparticles within the nanofluid, the larger the velocity repression due to more potent magnetic fields.

The Fig. 6 shows how the magnetic parameter (M) affects the velocity in the y-direction, g‘(η), for the two nanofluids: ternary hybrid nanofluid (THNF) and penta hybrid nanofluid (PHNF). Increasing the magnetic parameter causes the velocity g‘(η) to reduce due to the magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) effect, where the magnetic field exerts a resistive force against fluid motion. This is due to the interaction between the magnetic field and the charged particles in the fluid resulting in a Lorentz force that acts to resist the flow, reducing the velocity in the y-direction. PHNF, with more nanoparticles than THNF, has a greater decrease in velocity. PHNF’s greater nanoparticle content further enhances the fluid’s viscosity and renders the fluid more resistant to flow when exposed to the magnetic field. Therefore, the slowdown of velocity is more pronounced in PHNF compared to THNF with the rise of the magnetic parameter.

The Fig. 7 illustrates the influence of the magnetic parameter (M) on the temperature profile, θ(η). As M increases, the temperature profile θ(η) rises due to the MHD effect. A resistive force is generated in the magnetic field that reduces fluid velocity and results in lower convective heat transfer. When the flow is reduced, the thermal boundary layer thickness will be higher, resulting in an increase in temperature in this region. Furthermore, the higher viscosity of the fluid with the effect of the magnetic field also slows down the flow, enhancing the effect of a higher thermal boundary layer thickness. This increases the temperature of the boundary layer with an increasing magnetic parameter.

The Fig. 8 shows the effect of the magnetic parameter (M) on the concentration profile, ϕ(η), of two nanofluids: ternary hybrid nanofluid (THNF) and penta hybrid nanofluid (PHNF). The concentration profile is reduced by increasing the magnetic parameter. The MHD effect reduces the fluid velocity that subsequently reduces the convective transport of nanoparticles and lowers the concentration at the boundary layer. The difference in behavior of the concentration profiles of PHNF and THNF is due to higher nanoparticle content in PHNF. PHNF contains more nanoparticles, resulting in higher viscosity leading to high flow resistance. The higher resulting viscosity produces higher flow resistance, hence slower convective transport of particles, reducing the concentration faster for PHNF than THNF when the magnetic parameter increases. In addition, the higher concentration of nanoparticles in PHNF creates a higher degree of interaction with the magnetic field and increases suppression of the concentration profile.

The Fig. 9 shows the impact of the magnetic parameter (M) on the microorganisms’ profile, ψ(η). As the magnetic parameter is increased, the microorganisms’ concentration decreases due to the MHD effect, since the magnetic field generates the resistive force to slow down the fluid flow velocity. The reduction in the fluid velocity decreases the convective transport of microorganisms and leads to the decline in their concentration in the boundary layer. Also, the increased viscosity because of the greater magnetic parameter further suppresses the flow, increasing the suppression of microorganism concentration. The difference between PHNF and THNF is that PHNF, which has a higher nanoparticle concentration, experiences a greater suppression of microorganism transport. The higher nanoparticle concentration increases the fluid viscosity, causing a more significant reduction in microorganism concentration with the increase in the magnetic parameter.

The Fig. 10 indicates the effect of the porous factor (K) on the velocity profile, f‘(η). The velocity f ‘(η) reduces when the porous factor K increases as porous media provide higher resistance to the flow of fluids. An increase in the porous factor indicates a denser or more limiting porous medium, increasing the frictional resistance between the solid matrix and the fluid such that the velocity of the fluid is reduced. The resistance becomes greater with an increase in K because the flow encounters more obstructions in passing through and is therefore slowed down. By increasing K from 0.1 to 1.4 at η = 1, the velocity in the x direction decreases by 32.59%. The sole distinction of THNF from PHNF lies in the fact that PHNF, with its higher nanoparticles, exhibits a faster velocity decrease upon increasing K. This is the reason that a higher proportion of nanoparticles in PHNF raises fluid viscosity even further, and by extension, makes the flow resistance in porous media even higher. Therefore, the response of PHNF is one of an even higher velocity drop than that of THNF under the increase in porous factor.

The Fig. 11 demonstrates the effect of the porous factor (K) on the y-direction velocity profile, g‘(η). As the porous factor K increases, the velocity decreases due to increased resistance caused by the porous medium. The porous factor increases with a rise in the restrictiveness or density of the porous medium, resulting in increased frictional resistance between the solid matrix and fluid, thus impeding the fluid flow. This leads to a decrease in the velocity profile. By increasing K from 0.1 to 1.4 at η = 1, the velocity in the y-direction decreases by 33.55%. Additionally, PHNF, which has more nanoparticles than THNF, also has a larger drop in velocity as K increases. The additional nanoparticles in PHNF cause the fluid to become more viscous, adding to the flow resistance in the porous medium. Therefore, as more nanoparticles in the fluid mean that the more vigorous the suppression of velocity, the more strengthened is the porous condition.

Figure 12 depicts the effect of the porous parameter (K) on the temperature profile, θ(η). With the increase in K, the temperature profile improves and is due to the higher resistance to fluid flow in the porous medium. Larger value of K describes a denser porous medium that resists the fluid flow and improves the thermal boundary layer. This leads to improved heat retention and improved temperature profile in the boundary layer. Reduced velocity due to increased K makes the fluid spend more time in the porous medium, which provides more time for heat transfer to occur, thereby increasing the temperature near the surface. As K increases from 0.1 to 1.4 at η = 0.5, the temperature increases by 21.29%. Additionally, PHNF with increased nanoparticle volume fraction shows more improvement in temperature for increased K than THNF. The superior nanoparticles in PHNF enhance thermal conductivity, which leads to better heat transfer and hence the temperature profile increases more rapidly with K for PHNF.

The Fig. 13 depicts the effect of the porous factor (K) on the concentration profile, φ(η). A rise in the value of the porous factor K corresponds to a rise in the concentration profile φ(η). This is because higher K signifies a denser porous structure, where the fluid flow is hindered, resulting in extended residence of fluid within the porous material. The increased flow resistance causes the particles to move more slowly, so that there is more time for diffusion and hence the concentration in the boundary layer increases. By increasing K from 0.1 to 1.4 at η = 2, the concentration profile increases by 42.47%. Moreover, the extra nanoparticles in PHNF enhance particle retention of the fluid such that the increase in concentration becomes larger than that of THNF as the porous factor is increased. This is due to the rise in viscosity in PHNF, which also results in the raised concentration profile when K is raised.

The Fig. 14 illustrates the effect of the porous factor (K) on the microorganism profile, ψ(η). The microorganism profile ψ(η) rises as the porous factor K is raised. A rise in the porous factor contributes to a denser or more limiting porous medium, which enhances the diffusion process. The increased resistance to flow reduces the fluid’s speed, providing more time for the microorganisms to deposit, thus creating a higher concentration near the boundary layer. This is higher for PHNF than THNF. The higher nanoparticle content in PHNF increases the fluid viscosity, reducing the flow velocity and increasing the microorganism concentration further, hence leading to an increased rise in the microorganism profile with increasing K.

The Fig. 15 shows the effect of the ratio parameter (α) on the secondary velocity profile, g‘(η). When α increases, the secondary velocity profile g‘(η) increases. This is due to the fact that α is a ratio of secondary velocity constant (b) and primary velocity constant (a), with α and a being inversely related, and α and b being directly related. With an increase in α, there is a decrease in a, which causes the primary velocity profile to decrease, and b to increase, increasing the secondary velocity profile. The result is that as α increases, g‘(η) becomes more dominant, and the secondary direction flow is enhanced while the primary velocity is reduced. The effect is stronger for PHNF than for THNF since the higher concentration of nanoparticles in PHNF results in a larger difference in the velocity profiles with increasing α.

The Fig. 16 demonstrates the influence of the ratio parameter (α) on the temperature profile, θ(η). As α is increased, the temperature profile θ(η) is reduced. This is due to the fact that α is the ratio of the secondary velocity constant (b) to the primary velocity constant (a). As α is increased, the primary velocity constant (a) is reduced, and the capacity of the primary flow to transfer heat is reduced. In parallel, the rise in α also increases the secondary velocity constant (b), affecting the secondary flow but with lesser contribution to overall heat transfer. The reduction in primary flow velocity reduces heat convection in the boundary layer, decreasing the temperature. The effect is more pronounced in PHNF than in THNF, with PHNF exhibiting a greater extent of temperature decrease due to the greater concentration of nanoparticles that increases viscosity and also inhibits heat transfer. Therefore, as α increases, the temperature decreases more quickly in PHNF than in THNF.

The Fig. 17 demonstrates the effect of the parameter of ratio (α) on the concentration profile, φ(η). The concentration profile decreases as α increases. This is because a rise in α means a rise in the secondary velocity constant (b), which enhances the secondary flow. But the increase in α also leads to the reduction of the primary velocity constant (a), so the fluid travels more slowly in the primary direction. The slower primary flow reduces the efficiency of the convective transport of particles or solutes, and therefore the concentration drops in the boundary layer.

The Fig. 18 reveals the influence of the ratio parameter (α) on the profile of the microorganism, ψ(η). As α increases, the concentration of the microorganisms decreases due to the reverse relationship between α and the major velocity constant (a), which decreases the flow speed. With increasing α from 0.1 to 0.3 at η = 1, the microorganism profile decreases by 18.39%. The effect is more pronounced in PHNF compared to THNF due to the fact that the higher concentration of nanoparticles in PHNF leads to greater resistance and greater inhibition of the microorganism concentration.

Figure 19 shows the effect of the heat source parameter (Q) on temperature profile, θ(η). The temperature profile is higher as Q increases, i.e., temperature within the boundary layer is raised. This occurs since a greater heat source introduces thermal energy into the fluid, which increases heat transfer to the surrounding fluid layers, hence the temperature near the surface is raised. Moreover, the impact is stronger in PHNF than in THNF due to the higher concentration of nanoparticles in PHNF, which increases the thermal conductivity of the fluid. Therefore, the boundary layer temperature is increased further with the rising Q, resulting in a higher temperature increase in PHNF than in THNF.

The Fig. 20 depicts the effect of the radiation parameter (Rd) on the temperature profile, θ(η). The temperature profile increases with a rise in the radiation parameter. This is due to the fact that a higher Rd means greater heat radiation, and consequently promotes more heat transfer from the fluid to the surrounding environment. The result of this is that there is a rise in boundary layer temperature. This effect is stronger in PHNF compared to THNF. The higher nanoparticle concentration in PHNF strengthens the heat conduction ability of the fluid, which further increases the heat transfer and creates a greater rise in the temperature profile with increasing Rd in PHNF. Therefore, for increasing Rd, the temperature increases more for PHNF compared to THNF.

Figure 21 depicts how an increase in the parameter of thermophoresis (Nt) raises the profile of concentration, φ(η), due to an enhanced thermophoretic effect resulting from larger values of Nt, with consequent particle movement into the low temperature zones. Increasing the value of Nt results in a higher concentration of particles near the boundary layer, leading to a more compact distribution and increased area concentration. By increasing Nt from 0.1 to 0.14 at η = 2, the concentration profile improves by 25.53%. It happens to a greater degree for THNF as opposed to PHNF. In THNF, with low nanoparticles, the thermophoretic effect is stronger and can cause a larger increase in concentration with increasing Nt. In PHNF, with increased nanoparticle concentration, the increased viscosity and flow resistance cause less pronounced increase in the concentration profile with Nt. The higher viscosity in PHNF decreases particle motion towards the boundary, and this restricts the effect of thermophoresis on particle buildup, thus causing a reduced rise in the concentration profile compared to THNF.

The influence of the Brownian motion parameter (Nb) on the temperature profile, θ(η), is demonstrated in the Fig. 22. As Nb increases, the temperature profile increases. The reason lies in the fact that an increase in Nb means an increase in the Brownian motion of the nanoparticles within the fluid, followed by increased energy transfer and heat distribution throughout the fluid. Therefore, the surface temperature is raised due to the fact that the particles are more mobile and transferring energy at a faster rate. This occurs more in PHNF than in THNF. PHNF with a higher concentration of nanoparticles experiences the Brownian motion rise more, resulting in increased thermal conduction and elevated temperature level. The greater concentration of nanoparticles in PHNF enhances the rate of heat transfer, thus producing a steeper rising temperature profile with Nb, compared to THNF whose effect is not as pronounced due to fewer nanoparticles.

The Fig. 23 shows the effect of the Brownian motion parameter (Nb) on the concentration profile, φ(η). Increasing Nb reduces the concentration profile. This is due to the fact that increasing Nb means there is more intense Brownian motion of the nanoparticles, leading to a higher degree of dispersion and a more even particle distribution in the fluid. Therefore, particles are denser nearer to the boundary layer, and the concentration is higher. The effect is greater in PHNF compared to THNF because there is a higher concentration of nanoparticles in PHNF. With a greater number of nanoparticles in PHNF, there is greater Brownian motion, which increases particle dispersion even more, resulting in a greater reduction in the concentration profile nearer to the boundary layer. In contrast to this, THNF with fewer nanoparticles has a smaller reduction in concentration with increasing Nb.

The Fig. 24 displays the effect of the Schmidt number (Sc) on the concentration profile, φ(η). Increasing Schmidt number reduces the concentration profile. The Schmidt number is defined as the ratio of momentum diffusivity (kinematic viscosity) to mass diffusivity. A large Sc reflects that the mass diffusivity is low relative to the momentum diffusivity, which means slow particle diffusion in the fluid. As Sc increases, the particles increasingly find it difficult to diffuse inside the fluid, leading to a reduced concentration at the boundary layer. By increasing Sc from 1 to 1.2 at η = 2, the concentration profile decreases by 23.16%.

The Fig. 25 signifies the effect of the Lewis number (Lb) on the microorganisms’ profile, ψ(η). As the Lb parameter increases, the microorganisms’ profile decreases. The Lewis number is a ratio of thermal diffusivity to mass diffusivity. When Lb is greater, it implies that thermal diffusivity is greater than mass diffusivity, and heat diffuses more quickly than particles. As a result, the rise in heat transfer effectiveness leads to more uniform distribution of temperature throughout the fluid, which reduces convective transport of microorganisms into the boundary layer. This reduction of ability to concentrate microorganisms near or at the surface leads to a decrease in their profile.

The Fig. 26 shows the effect of the Peclet number (Pe) on microorganism profile, ψ(η). With a rise in the Peclet number, the microorganism profile decreases. The Peclet number is a ratio of convective to diffusive transport. With a rise in the Peclet number, there is more convective flow than diffusion. As Pe rises, the fluid velocity rises, leading to quicker transport of microorganisms away from the boundary layer. Therefore, the microorganisms are less dense close to the surface, and hence the concentration profile decreases.

The comparison between PHNF and THNF at different values of parameters in \({C_{fx}}{\operatorname{Re} _x}^{{1/2}}\), \({C_{fy}}{\operatorname{Re} _y}^{{1/2}}\), and \(N{u_x}{\operatorname{Re} _x}^{{ - 1/2}}\) is shown in Figs. 27, 28 and 29. The figures indicate better performance of PHNF compared to THNF.

Conclusion

In the current study, we examine the penta hybrid nanofluid flow with the interaction of gyrotactic microorganisms along a stretching surface. To numerically solve the model, we utilize the bvp4c MATLAB solver. The application of this technique enables us to solve the system efficiently. Convective boundary conditions are used to calculate the mass and heat transfer rates to identify the transport phenomena. Apart from this, both porous medium and magnetic field effects are also considered in the model to see how they affect the flow dynamics. The influence of Brownian motion and thermophoretic forces on the nanoparticle volumetric fraction is also considered to give a deeper insight into the physical mechanisms involved in the flow. This study aims to extend the understanding of the interaction between these variables and their resultant effect on the overall flow regime behavior and heat transfer performance. Other than theoretic significance, this work has important practical relevance. The enhancement of heat transfer with the aid of PHNF can potentially be applied in high-efficiency systems for cooling such as compact heat exchangers, electronics cooling systems, and microfluidic heat sinks. The combination of gyrotactic microorganisms and bioconvective analysis also has potential application in biotechnology and biomedical systems where thermal and mass transport control are of critical significance such as in biosensors, drug delivery systems, or microbial fuel cells. The addition of porous media and magnetic fields in the model also has potential application in industrial processing in filtering, geothermal recovery, and magnetic separation. Future experimental and design-oriented work can be built from these results to develop new, adaptive fluid systems combining thermal performance with biological control and system stability for practical purposes. Some of the key findings of this study are as follows:

-

f’ and g’ decrease as the parameter M increases.

-

f’ and g’ decrease as the parameter K increases.

-

The temperature profile improves as the parameter K increases.

-

The concentration profile becomes better as the parameter K is raised.

-

The microorganism concentration increases as the parameter K is raised.

-

The velocity profile in the y direction improves as the parameter α is increased.

-

The temperature profile drops as the parameter α is increased.

-

The concentration profile falls as the parameter α increases.

-

The microorganism profile lowers as the parameter α increases.

-

The temperature profile becomes better as the radiation parameter is raised.

-

The temperature profile becomes better as the Brownian parameter is raised.

-

The concentration profile falls as the Brownian parameter rises.

-

The findings indicate that PHNF is more efficient than THNF.

Limitations

While the current investigation offers an extensive analysis of three-dimensional penta-hybrid nanofluid flowing over a stretching surface with interaction of gyrotactic microorganism, a few intrinsic limitations in the model formulation must be noted. First, the nature of the flow regime is postulated to be laminar and steady, thus eliminating the possibility of any turbulence-induced effects, which are normally experienced in high-velocity industrial or environmental fluid systems. Second, fluid behavior in the current analysis is presumed to be Newtonian, while a vast majority of practical suspensions of nanofluids happen to be non-Newtonian in nature under variable shear or high particle concentrations. Third, chemical reaction or reactive transport phenomena are also absent in the current model, while such phenomena play a critical significance in relevant cases like biochemical processing, catalytic reactors, and biomedical diagnostics. Further, surface rugosity, nanoparticle shape factor influence, and particle or nanoparticle stabilization by aggregation are also not treated explicitly, while these properties can play an important role in thermal as well as mass transport behavior. Such simplifications while mathematically obligatory reduce the direct suitability of the current model to complex or strongly reactive fluid domains. Future work must hence be geared toward overcoming these shortfalls by experimental confirmation, introduction of turbulent and non-Newtonian nature of fluid properties, and introduction of chemical kinetics and interfacial phenomena to present a more exact portrayal of hybrid nanofluid systems.

Future research direction

A future direction of study involves exploration of the potential impact of microorganisms on penta-hybrid nanofluids’ settling behavior, stability, and aggregation. While the present work models bio-convective behavior of gyrotactic microorganisms in a continuous framework, real microorganisms have the potential to interact with nanoparticles in complex ways beyond fluid mechanics. To underscore this, bioconvection induced by motile microorganisms has the potential to enhance fluid mixing and reduce nanoparticle settling and thereby enhance colloidal stabilization. Extracellular secretion by microbial activities can also alter surface properties of nanoparticles and thereby influence inter-particle forces and result in stabilization or enhanced aggregation. The mechanical effect of motile microorganisms has the potential to break down aggregates of clusters or induce nanoparticle collisions depending upon the regime of flow. Surface biofunctionalization by microbial contact or metabolites also has the potential to alter zeta potential and particle-particle interaction. These biologically mediated phenomena suggest that hybrid nanofluid’s microstructural dynamics can be substantially influenced by microorganism presence. Incorporating such interactions in future experimental or multiscale study will provide a richer understanding of microorganism-nanoparticle interaction in bio-convecting systems, drug delivery systems, or bio-technology-assisted heat and mass transport systems. Further, future work can involve turbulent flow simulation for the regulation of high-velocity industrial flows. Extension of models to non-Newtonian penta-hybrid nanofluids will allow for enhanced prediction in biofluids and complex suspensions. Incorporating reaction kinetics with chemical transport phenomena will also be important in simulating drug delivery systems or catalytic reactors. These activities will enhance the realism of the model and bring in new engineering and biomedical applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Choi, S. U. S. & Eastman, J. A. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. In 1995 Int. Mech. Eng. Congr. Exhib. San Fr. CA (United States), 12–17 Nov 1995 (1995).

Chu, Y., Bashir, S., Ramzan, M. & Malik, M. Y. Model-based comparative study of magnetohydrodynamics unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow between two infinite parallel plates with particle shape effects. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 46, 11568–11582 (2023).

Acharya, N., Mabood, F., Shahzad, S. A. & Badruddin, I. A. Hydrothermal variations of radiative nanofluid flow by the influence of nanoparticles diameter and nanolayer. Int. Commun. Heat. Mass. Tran. 130, 105781 (2022).

Rizwan, M., Hassan, M., Makinde, O. D., Bhatti, M. M. & Marin, M. Rheological modeling of metallic oxide nanoparticles containing non-Newtonian nanofluids and potential investigation of heat and mass flow characteristics. Nanomaterials 12, 1237 (2022).

Khan, A., Alyami, M. A., Alghamdi, W., Alqarni, M. M. & Yassen, M. F. Tag eldin, thermal examination for the micropolar gold–blood nanofluid flow through a permeable channel subject to gyrotactic microorganisms, front. Energy Res. 10, 993247 (2022).

Hussain, S. M. et al. Chemical reaction and thermal characteristics of Maxwell nanofluid flow-through solar collector as a potential solar energy cooling application: a modified buongiorno’s model. Energy Environ. 34, 1409–1432 (2023).

Eid, M. R. & Nafe, M. A. Thermal conductivity variation and heat generation effects on magneto-hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium with slip condition. Waves Random Complex. Media. 32, 1103–1127 (2022).

Elattar, S. et al. Computational assessment of hybrid nanofluid flow with the influence of hall current and chemical reaction over a slender stretching surface. Alex Eng. J. 61, 10319–10331 (2022).

Abbasi, A. et al. Heat transport exploration for hybrid nanoparticle (Cu, Fe3O4)—based blood flow via tapered complex wavy curved channel with slip features. Micromachines 13, 1415 (2022).

Kanti, P. K. & Maiya, M. P. Rheology and thermal conductivity of graphene oxide and coal fly Ash hybrid nanofluids for various particle mixture ratios for heat transfer applications: experimental study. Int. Commun. Heat. Mass. Tran. 138, 106408 (2022).

Algehyne, E. A. et al. On thermal distribution of MHD mixed convective flow of a Casson hybrid nanofluid over an exponentially stretching surface with impact of chemical reaction and ohmic heating. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1–14 (2023).

Ismail, M. F., Azmi, W. H., Mamat, R., Ab, R. & Rahim Rheological behaviour and thermal conductivity of Polyvinyl ether lubricant modified with SiO2-TiO2 nanoparticles for refrigeration system. Int. J. Refrig. 138, 118–132 (2022).

Waqas, H. et al. Heat transfer analysis of hybrid nanofluid flow with thermal radiation through a stretching sheet: a comparative study. Int. Commun. Heat. Mass. Tran. 138, 106303 (2022).

Rehman, M. I. U., Chen, H., Hamid, A. & Qi, H. Numerical analysis of unsteady non-linear mixed convection flow of reiner-philippoff nanofluid along Falkner-Skan wedge with new mass flux condition. Chem. Phys. Lett. 830, 140799 (2023).

Mahboobtosi, M., Hosseinzadeh, K. & Ganji, D. D. Investigating the convective flow of ternary hybrid nanofluids and single nanofluids around a stretched cylinder: parameter analysis and performance enhancement. Int. J. Thermofluids. 23, 100752 (2024).

Mahboobtosi, M., Hosseinzadeh, K. & Ganji, D. D. Entropy generation analysis and hydrothermal optimization of ternary hybrid nanofluid flow suspended in polymer over curved stretching surface. Int. J. Thermofluids. 20, 100507 (2023).

Mahboobtosi, M. et al. Entropy generation analysis of kerosene oil flow with ternary hybrid nanoparticles on the stretchable exponential surface. Int. J. Model. Simul. 1–15 (2024).

Ganji, D., Domiri, M., Mahboobtosi & Fateme Nadalinia Chari. Nonlinear radiation in entropy generation MHD flow of penta-hybrid nanofluids: effects of variable thermal conductivity, viscous dissipation and nonlinear convection. J. Radiation Res. Appl. Sci. 18 (2), 101524 (2025).

Rehman, K. U., Shatanawi, W. & Al-Mdallal, Q. M. A comparative remark on heat transfer in thermally stratified MHD Jeffrey fluid flow with thermal radiations subject to cylindrical/plane surfaces, case stud. Therm. Eng. 32, 101913 (2022).

Mishra, S., Mondal, H. & Kundu, P. K. Analysis of activation energy and microbial activity on couple stress nanofluid with heat generation. Int. J. Ambient Energy. 45, 2266429 (2024).

Mishra, S., Mondal, H. & Kundu, P. K. Unsteady bioconvection microbial nanofluid flow in a revolving vertical cone with chemical reaction. Pramana 98, 12 (2024).

Mishra, S., Mondal, H. & Kundu, P. K. Impact of microbial activity and stratification phenomena on generating/absorbing sutterby nanofluid over a Darcy porous medium. J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 9, 804–819 (2023).

Sharma, B. K., Kumar, A., Gandhi, R., Bhatti, M. M. & Mishra, N. K. Entropy generation and thermal radiation analysis of EMHD Jeffrey nanofluid flow: applications in solar energy. Nanomaterials 13, 1–23 (2023).

Hussain, M., Farooq, U. & Sheremet, M. Nonsimilar convective thermal transport analysis of EMHD stagnation Casson nanofluid flow subjected to particle shape factor and thermal radiations. Int. Commun. Heat. Mass. Tran. 137, 106230 (2022).

Akbar, S. & Sohail, M. Three dimensional MHD viscous flow under the influence of thermal radiation and viscous dissipation. Int. J. Emerg. Multidiscip Math. 1, 106–117 (2022).

Yaseen, M., Rawat, S. K., Shafiq, A., Kumar, M. & Nonlaopon, K. Analysis of heat transfer of mono and hybrid nanofluid flow between two parallel plates in a Darcy porous medium with thermal radiation and heat generation/absorption. Symmetry (Basel) 14, 1943 (2022).

Bilal, M. et al. Williamson Magneto nanofluid flow over partially slip and convective cylinder with thermal radiation and variable conductivity. Sci. Rep. 12, 12727 (2022).

Oluwaseun, F., Goqo, S. & Mondal, H. Unsteady squeezing flow and heat transport of SiO2/kerosene oil nanofluid around radially stretchable parallel rotating disks with upper disk oscillating, propuls. Power Res. 13, 64–79 (2024).

Mishra, S. & Mondal, H. Rotational microorganism magneto-hydrodynamic nanofluid flow with Lorentz and Coriolis force on moving vertical plate. Bionanoscience 1–18 (2024).

Mandal, A., Mondal, H. & Tripathi, R. A mathematical model of magneto hydrodynamics unsteady nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic micro-organism through a bidirectional stretching sheet. Bionanoscience 1–18 (2024).

Rehman, M. I. U., Chen, H. & Hamid, A. Multi-physics modeling of magnetohydrodynamic Carreau fluid flow with thermal radiation and Darcy–Forchheimer effects: a study on Soret and dufour phenomena. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 148, 13883–13894 (2023).

Chari, F. et al. Heat transfer analysis of go/water nanofluid flow under the influence of joule heating and chemical reactions with MHD: analytical and numerical concept. Multiscale Multidisciplinary Model. Experiments Des. 8 (5), 264 (2025).

Mahboobtosi, M. et al. Investigate the influence of various parameters on MHD flow characteristics in a porous medium. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 59, 104428 (2024).

Ganji, D. et al. Heat transfer analysis of magnetized fluid flow through a vertical channel with thin porous surfaces: Python approach. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 60, 104643 (2024).

Mahboobtosi, M. et al. Heat transfer characteristics in the squeezing flow of Casson fluid between circular plates: A comprehensive study. Adv. Mech. Eng. 16 (10), 16878132241290942 (2024).

Shateri, A. et al. Thermal analysis of unsteady viscous flow in medical engineering: A comparative analysis of numerical and semi-analytical methods. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2550120 (2025).

Hosseinzadeh, K. et al. Optimization of antenna-shaped fins configuration for enhanced solidification in triplex thermal energy storage systems with radiative heat transfer. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 64, 105488 (2024).

Jalili, P. et al. A comparative study of hybrid analytical and Laplace transform approaches for solving partial differential equations in Python. Int. J. Eng. Trnsactions B: Appl. 37 (2), 352–364 (2024).

Algehyne, E. A., Alhusayni, Y. Y., Tassaddiq, A., Saeed, A. & Bilal, M. The study of nanofluid flow with motile microorganism and thermal slip condition across a vertical permeable surface. Waves Random Complex Media 1–18 (2022).

Chen, K. & Qin, K. Microbial transport and dispersion in heterogeneous flows created by pillar arrays. Phys. Fluids 34 (2022).

Elbashbeshy, E. M. A. & Asker, H. G. Fluid flow over a vertical stretching surface within a porous medium filled by a nanofluid containing gyrotactic microorganisms. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 137, 541 (2022).

Khan, A. et al. Bioconvection Maxwell nanofluid flow over a stretching cylinder influenced by chemically reactive activation energy surrounded by a permeable medium. Front. Physiol. 10, 1348 (2023).

Lone, S. A., Anwar, S., Saeed, A. & Bognar, G. ´ A stratified flow of a non-Newtonian Casson fluid comprising microorganisms on a stretching sheet with activation energy. Sci. Rep. 13, 11240 (2023).

Rehman, M. I. U., Chen, H. & Hamid, A. Impact of bioconvection on Darcy-Forchheimer flow of MHD Carreau fluid with arrhenius activation energy. ZAMM-Journal Appl. Math. Mech. Für Angew Math. Und Mech. 104, e202300164 (2024).

Madhu, J., Baili, J., Kumar, R. N., Prasannakumara, B. C. & Gowda, R. J. P. Multilayer neural networks for studying three-dimensional flow of non-Newtonian fluid flow with the impact of magnetic dipole and gyrotactic microorganisms. Phys. Scripta. 98, 115228 (2023).

Boujelbene, M. et al. Effect of electrostatic force and thermal radiation of viscoelastic nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms surrounded by PST and PHF: Bacillus anthracis in biological applications, case stud. Therm. Eng. 52, 103691 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Melting thermal transportation in bioconvection Casson nanofluid flow over a nonlinear surface with motile microorganism: application in bioprocessing thermal engineering, case stud. Therm. Eng. 49, 103285 (2023).

Akolade, M. T., Olabode, J. O., Tijani, Y. O. & Akhtar, T. Bioconvection in Eyring–Powell fluid with composite features of variable viscosity and motile microorganism density. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 138, 1–16 (2023).

Patil, P. M., Goudar, B. & Momoniat, E. Magnetized bioconvective micropolar nanofluid flow over a wedge in the presence of oxytactic microorganisms, case stud. Therm. Eng. 49, 103284 (2023).

Waqas, H. et al. Numerical computation of brownian motion and thermophoresis effects on rotational micropolar nanomaterials with activation energy. Propuls. Power Res. (2023).

Sharma, B. K., Khanduri, U., Mishra, N. K. & Mekheimer, K. S. Combined effect of thermophoresis and brownian motion on MHD mixed convective flow over an inclined stretching surface with radiation and chemical reaction. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B. 37, 2350095 (2023).

Thabet, E. N., Khan, Z., Abd-Alla, A. M. & Bayones, F. S. Thermal enhancement, thermophoretic diffusion, and brownian motion impacts on MHD micropolar nanofluid over an inclined surface: numerical simulation. Numer. Heat. Transf. 1–20 (2023).

Shahzad, A. et al. Brownian motion and thermophoretic diffusion impact on Darcy-Forchheimer flow of bioconvective micropolar nanofluid between double disks with Cattaneo-Christov heat flux. Alex Eng. J. 62, 1–15 (2023).

Almeida, F., Gireesha, B. J. & Venkatesh, P. Magnetohydrodynamic flow of a micropolar nanofluid in association with brownian motion and thermophoresis: irreversibility analysis. Heat. Transf. 52, 2032–2055 (2023).

Tawade, J. V. et al. Effects of thermophoresis and brownian motion for thermal and chemically reacting Casson nanofluid flow over a linearly stretching sheet. Results Eng. 15, 100448 (2022).

Madhura, K. R. & Babitha, A. Numerical study on magnetohydrodynamics micropolar Carreau nanofluid with brownian motion and thermophoresis effect. Int. J. Model. Simul. (2023).

Hazarika, S. & Ahmed, S. Brownian motion and thermophoresis behavior on micro-polar nano-fluid—a numerical outlook. Math. Comput. Simulat. 192, 452–463 (2022).

Khan, S. A., Hayat, T. & Alsaedi, A. Thermal radiation impact on chemical reactive flow of micropolar nanomaterial subject to brownian diffusion and thermophoresis phenomenon. J. Comput. Sci. 102094 (2023).

Madkhali, H. A. et al. Computational study on the effects of brownian motion and thermophoresis on thermal performance of cross fluid with nanoparticles in the presence of ohmic and viscous dissipation in chemically reacting regime. Comput. Part. Mech. 1–11 (2023).

Suma, U. K., Katun, M. & Biswas, R. Consequences of thermophoresis, and brownian motion on MHD heat and mass transfer of jeffrey’s nano-fluid flow via a perpendicular plate. Asian J. Pure Appl. Math. 5, 414–429 (2023).

Rehman, M. I. U. et al. Thermal and solutal slip impacts of tribological coatings on the flow and heat transfer of reiner-philippoff nanofluid lubrication toward a stretching surface: the applications of Darcy-Forchheimer theory. Tribol Int. 190, 109038 (2023).

Ur Rehman, M. I. et al. Darcy–Forchheimer aspect on unsteady bioconvection flow of Reiner–Philippoff nanofluid along a wedge with swimming microorganisms and arrhenius activation energy. Numer. Heat. Transf. 1–19 (2024).

Kumar, M. D., Raju, C. S. K., Shah, N. A., Yook, S. J. & Gurram, D. Support vector machine learning classification of heat transfer rate in tri-hybrid nanofluid over a 3D stretching surface with Suction effects for water at 10° C and 50° C. Alexandria Eng. J. 118, 556–578 (2025).

Kumar, M. D. et al. Forecasting heat and mass transfer enhancement in magnetized non-Newtonian nanofluids using Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm: influence of activation energy and bioconvection. Mech. Time-Dependent Mater. 29 (1), 14 (2025).

Kumar, M. D., Gurram, D., Yook, S. J., Raju, C. S. K. & Shah, N. A. Optimizing Thermal Performance of Water-Based Hybrid Nanofluids with Magnetic and Radiative Effects Over a Spinning Disc105336 (Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 2025).

Kumar, M. D., Dharmaiah, G., Yook, S. J., Raju, C. S. K. & Shah, N. A. Deep learning approach for predicting heat transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid thin film flow and optimization via response surface methodology. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 68, 105930 (2025).

Wang, C. Y. The three-dimensional flow due to a stretching flat surface. Phys. Fluids. 27 (8), 1915–1917 (1984).

Liu, I. C. & Andersson, H. I. Heat transfer over a bidirectional stretching sheet with variable thermal conditions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 51 (15–16), 4018–4024 (2008).

Khan, N. M. et al. Dynamics of radiative Eyring-Powell MHD nanofluid containing gyrotactic microorganisms exposed to surface Suction and viscosity variation. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 28, 101659 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Davood Domiri Ganji: Supervision, Project administration. Mehdi Mahboobtosi: Validation, Software, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Fateme Nadalinia Chari: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ganji, D.D., Mahboobtosi, M. & Chari, F.N. Three-dimensional flow analysis of penta and ternary-hybrid nanofluids over an elongating sheet with thermal radiation and gyrotactic microorganisms. Sci Rep 15, 24396 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09009-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09009-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Nonlinear magneto-radiative bioconvection of Casson penta-hybrid nanofluid with microorganisms under inclined magnetic field and quadratic radiation for drug delivery

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Entropy generation analysis and magneto-thermal investigation of eyring–powell PHNF with bioconvective gyrotactic microorganisms with analytical modeling: applications in microchannel heat exchangers and biomedical cooling systems

Multiscale and Multidisciplinary Modeling, Experiments and Design (2026)

-

Three-dimensional flow analysis over stretching sheet with nonlinear thermal radiation and penta-hybrid nanofluid for polymer manufacturing application

Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry (2026)

-

Thermally stratified flow of unsteady magnetized nanofluids within squeezing channel with Darcy Forchhimer porous medium

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Entropy and heat transfer in (SWCNTs)/(C2H6O2–H2O) 50:50% dissipative nanofluidic system: application of Kyamada–ota model

Scientific Reports (2025)