Abstract

Adopting agricultural green production technologies (AGPTs) is crucial for enhancing agricultural sustainability. This study draws on data from 1281 rice farmers in Jiangxi Province, China, surveyed in 2023. Using multivariate ordered probit models and mediated effects models, it examines whether cooperative membership affects the utilization of AGPTs. The findings reveal that the means of sample farmers’ adoption of AGPTs and cooperative membership are 0.764 and 0.234, respectively, indicating that the adoption rate of AGPTs and the cooperative participation rate among farmers are relatively low. Cooperative membership, along with services such as land transfer, agricultural input procurement, production technology, and product marketing, significantly promotes the use of AGPTs. Specifically, cooperative membership encourages the adoption of organic fertilizers, soil-formula fertilizers, water-fertilizer integration, and green pest control technologies. However, it has no significant influence on the uptake of water-saving irrigation technologies. The impact of cooperative membership is powerful among farmers with lower educational attainment and in villages with higher economic levels. Additionally, cooperative membership enhances the application of AGPTs by improving farmers’ environmental awareness, risk attitude, operational scale, and credit accessibility. Therefore, the government should encourage farmers to actively adopt AGPTs through measures such as supporting the development of cooperatives and improving the quality of their services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The widespread utilization of agrochemicals, such as pesticides and fertilizers, has significantly boosted crop yields and contributed to global food security1,2. However, excessive agrochemical inputs have also led to environmental degradation and health risks. Overuse of pesticides is strongly linked to respiratory diseases, cancer, and neurological disorders. Similarly, chemical fertilizers degrade soil quality3 and contribute to greenhouse gas emissions4. Recent studies suggest that adopting agricultural green production technologies (AGPTs) is crucial for decreasing the reliance on these harmful inputs5,6.

Despite government efforts to promote green agriculture, farmers’ adoption of these technologies remains limited7,8. AGPTs have clear positive externalities, yet factors such as high initial investment, long payback periods, and constraints on capital and technical knowledge deter farmers from adopting them9. With the increasing support from national policies, farmer professional cooperatives have become a new engine for promoting green agricultural development and rural industrial prosperity and play a crucial role in improving farmers’ livelihood capital. By the end of 2022, the number of existing cooperatives in China reached 2.2436 million, an increase of 0.65% over 2021. However, while the number of cooperatives has surged, the proportion of “shell cooperatives” has also increased. Most farmers only hold the status of cooperative members but cannot enjoy the rights and services they are entitled to as members. Therefore, exploring the impact of cooperative membership on farmers’ adoption of AGPTs and their influencing pathways is of significant practical importance for promoting the transformation of agricultural production towards green and sustainable methods and achieving high-quality agricultural development.

Researchers have examined a wide range of factors that affect farmers’ utilization of AGPTs. Key determinants include personal characteristics such as gender10, age11, education12, time preference13, risk attitude14, and environmental awareness15. Other factors include agricultural income16, labor migration17, social networks18, agricultural insurance19, technical training20, land fragmentation21, and external influences like consumer preferences22 and policy incentives23.

For instance, Wang et al. (2021) discovered that farmers’ capital endowment and environmental awareness promote the acceptance of environmentally friendly technologies in apple farming24. Similarly, Wang et al. (2020) indicated that risk-tolerant farmers are more inclined to incur the costs of biodegradable land films14. Li et al. (2020) underscored the significance of perceived value in driving the utilization of AGPTs25. The importance of agriculture to household income also influences farmers’ likelihood of adopting sustainable practices16. Social norms and networks play a role in facilitating green control technologies18, while agricultural insurance and technical training further encourage the utilization of green practices19,20. Consumer preferences and policy incentives also drive farmers to use AGPTs actively22,23. However, some studies present contrasting findings. Mao et al. (2021) found that time preference reduces farmers’ utilization of AGPTs13. Similarly, labor migration can limit the use of water and soil conservation methods17, and land fragmentation can increase fertilizer use21.

Participation in agricultural cooperatives has enhanced farmers’ use of AGPTs26. Cooperatives can lower input costs and mitigate risks while promoting new technologies through training, demonstration, and peer exchange27. Yu et al. (2021) demonstrated that cooperative involvement promotes vegetable farmers to adopt green control technologies28. Similarly, Li et al. (2021) and Zhang et al. (2020) discovered that cooperative membership can foster farmers’ use of organic fertilizers and environmentally friendly production methods29,30. The mechanisms through which cooperatives influence AGPTs adoption include increased environmental awareness31, risk expectations32, external regulations33, and enhanced technical capabilities34.

In summary, previous studies have laid a solid foundation for this research. However, there is still room for further exploration. First, most studies have only focused on the impact of cooperative membership or single cooperative services on farmers’ utilization of AGPTs, ignoring the combined effects of different cooperative services. Second, few studies have examined the differentiated impacts of cooperative involvement on adopting different AGPTs. Third, the heterogeneous effects of cooperative membership on farmers’ technology adoption behavior under various conditions remain to be explored. Fourth, the influence mechanisms through which cooperative membership promotes farmers’ adoption of AGPTs have not been fully discussed, neglecting the mediating roles of risk attitude, cultivation scale, and credit accessibility. Most discussions have been conducted from a single internal perspective (such as environmental awareness) or external perspective (such as external regulations).

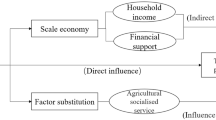

Risk attitude, operational scale, and credit accessibility may play mediating roles in the impact of cooperative membership on farmers’ utilization of AGPTs, possibly because cooperatives form risk-sharing mechanisms through organized operations to reduce the risks of technology adoption for farmers. Meanwhile, cooperatives help farmers expand production scale through resource integration to form economies of scale and reduce the marginal cost of technology adoption. In addition, cooperatives providing credit guarantees can alleviate farmers’ financial constraints to enhance their capacity for technology investment. These three pathways construct a transmission bridge between cooperative membership and technology adoption behavior from the perspectives of risk preference effects, economies of scale effects, and financial leverage effects, respectively. This research’s significance is that it strengthens cooperatives’ functions in optimizing members’ risk attitude, promoting moderate-scale operations, and improving credit availability. It can specifically address the risk-averse mentality, diseconomies of scale bottlenecks, and financial constraint barriers that hinder farmers’ adoption of AGPTs. This provides theoretical support and practical pathways for achieving the goals of agricultural green transformation and sustainable development.

This study addresses these gaps based on the research data from farmers in Jiangxi Province, China, collected in 2023. It employs multivariate ordered probit models and mediation effect tests to analyze how cooperative membership and services—such as land transfer, agricultural procurement, production technology, and marketing—affect the use of green technology. Meanwhile, this study will further investigate the differentiated impacts of cooperative membership on adopting different green production technologies and the heterogeneous effects on technology adoption behavior under various conditions. Additionally, this study analyzes the mechanism between cooperative membership and farmers’ adoption of AGPTs from both internal and external factors.

Jiangxi Province is a key rice-producing region in China, with an output of 20.365 million tons in 2022, ranking 3rd in the country. The Poyang Lake Plain is one of China’s major commercial grain production hubs. Between 2012 and 2022, the number of farmers’ cooperatives in Jiangxi grew from 19,100 to 79,000, with 56.9% involved in cultivation. This growth reflects Jiangxi’s significant achievements in cooperative development. By 2022, the total operating income of cooperatives in the province reached 18.37 billion yuan, with an average income of 234,000 yuan. These figures demonstrate cooperatives’ crucial role in promoting agricultural modernization and increasing farmers’ incomes. Therefore, selecting sample data from Jiangxi Province provides valuable insights into how cooperative participation influences rice farmers’ adoption of AGPTs.

This study contributes to the literature in several aspects. First, it examines the effect of cooperative membership on different AGPTs, offering a more nuanced understanding of how cooperatives influence technology adoption. Second, it explores how specific cooperative services affect green production, providing insights into the most beneficial services. Third, it investigates how cooperative involvement interacts with different contextual factors, such as education levels and local economic conditions, to influence AGPTs adoption. Finally, it analyzes the mediating roles of environmental awareness, risk attitude, operational scale, and credit accessibility in shaping farmers’ adoption behavior.

The subsequent sections of this paper are organized as follows: section “Conceptual analysis” comprises the theoretical examination and formulation of research hypotheses. In section “Research design”, the materials and procedures are presented. The findings and discussion are presented in section “Results and discussion”, while the conclusions and recommendations are provided in section “Conclusions and recommendations”.

Conceptual analysis

The direct effect of cooperative membership on farmers’ AGPTs adoption behavior

Farmers, as rational economic agents, prioritize profit when allocating production factors. The greater the financial gains from using green technology and the lower the costs, the greater the likelihood that farmers will embrace such technologies35. Cooperatives are essential in diminishing farmers’ production costs and enhancing returns by lowering input and transaction costs36. As mutual-aid organizations centered around agricultural producers, cooperatives act as a vital link between farmers and the modern agricultural system. Their efficient resource utilization and technology demonstration make them ideal for promoting agricultural technology37.

Cooperatives provide services across all stages of production—pre-production, mid-production, and post-production—effectively reducing farmers’ costs38. Technical training services offer farmers professional guidance to enhance agricultural skills39. Agricultural supply services provide a unified source for inputs such as pesticides, fertilizers, and equipment40. Agricultural product marketing services assist farmers in promoting and selling their products, helping them maximize value and access markets efficiently. Farmers engaged in cooperatives are better positioned to embrace new technologies due to improved access and affordability. The cooperative’s unique benefit distribution mechanism fosters consensus among members, aligning individual goals with the collective interest. This encourages proactive efforts toward the cooperative’s common objectives41. Thus, Hypothesis 1 is proposed:

H1 Cooperative membership significantly motivates farmers to embrace green technologies.

Mechanisms of cooperative membership on farmers’ AGPTs adoption behavior

According to systems theory, farmers’ decision-making is shaped by a combination of internal cognitive processes and external environmental conditions. The application of green technologies relies not only on farmers’ intrinsic motivation—whether they want to adopt these technologies—but also on their ability to overcome external constraints—whether they can adopt them42. This study argues that cooperative membership influences both internal factors, including farmers’ environmental awareness and risk attitude, and external factors, including operational scale and credit accessibility. By enhancing farmers’ awareness of green practices and increasing their willingness to take risks, cooperatives boost farmers’ intrinsic motivation to use green technologies. Simultaneously, cooperatives help farmers overcome practical barriers, such as a lack of economies of scale and financial constraints, enabling them to implement green practices.

Human capital theory highlights that training is essential for enhancing individual skills. Technical training offered by cooperatives motivates farmers to enhance their knowledge and environmental awareness27. Additionally, cooperatives enhance green awareness through incentives, information exchange, and standardized production practices43. Improving environmental awareness boosts farmers’ enthusiasm for adopting environmentally friendly technologies44. According to behavioral economics, cognition is key to making informed technology decisions. Enhanced green awareness increases farmers’ confidence in green technologies and reduces their fear of improper operation or uncertain outcomes45. When farmers understand that modern technologies improve product quality without sacrificing productivity, they are more inclined to accept green practices9. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is proposed:

H2 Cooperative membership significantly improves farmers’ environmental awareness, leading to greater adoption of green technologies.

Farmers face various risks in production and marketing, including natural and market-related uncertainties46. Due to limited information and resources, most farmers exhibit risk-averse behavior47,48. Agricultural cooperatives play a pivotal role in strengthening farmers’ risk resilience and fostering risk-taking propensity. By establishing linkages between farmers and enterprises, cooperatives enable risk-sharing mechanisms that collectively enhance stakeholders’ capacity to withstand and mitigate agricultural uncertainties49. On the other hand, cooperatives’ surplus distribution systems stabilize operations, fostering confidence in future income50. According to prospect theory, risk attitude strongly influence decision-making51,52. Risk-averse farmers tend to favor traditional, less risky practices, delaying the application of green technologies53. In contrast, risk-tolerant farmers are more willing to bear the uncertainties associated with adopting new technologies54. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is proposed:

H3 Cooperative membership significantly enhances farmers’ risk attitude, leading to greater adoption of green technologies.

Cooperatives offer numerous benefits, including cost savings, risk reduction, and financing support. These advantages encourage farmers to expand their cultivation scale through land rentals, facilitating large-scale management55. An expansion in operational size significantly enhances the likelihood of using environmentally friendly technologies56. Larger farms have greater access to information and fewer barriers to technology adoption. They are also better capitalized, enabling them to focus on long-term returns rather than short-term gains57. The economies of scale achieved by larger operations lower the marginal cost of using green technologies, reducing the financial burden of adoption58. Thus, Hypothesis 4 is proposed:

H4 Cooperative membership significantly increases operational scale, promoting the use of green technologies.

Cooperatives also enhance farmers’ access to both formal and informal credit59. In formal lending, cooperatives’ connections with financial institutions or online platforms provide credit guarantees, helping farmers secure formal loans and overcome financial constraints60,61. In informal lending, cooperatives foster close ties among members, facilitating access to informal credit networks. Studies show that improved credit availability significantly increases the likelihood of adopting green technologies. Credit alleviates financial constraints, lowering the barrier to technology adoption62. Additionally, credit accessibility increases liquidity, easing short-term capital pressures and encouraging adoption63. Thus, Hypothesis 5 is proposed:

H5 Cooperative membership significantly enhances farmers’ credit accessibility, promoting the use of green technologies.

This research develops a theoretical analysis framework diagram, as shown in Fig. 1, based on the preceding analysis.

Research design

Data source

This study is based on data from a field survey actualized by the Jiangxi Agricultural University between June and July 2023. To ensure representativeness, 24 counties (cities/districts) were selected as sample areas, covering 11 prefecture-level cities in Jiangxi Province (Fig. 2). The selected counties represented a diverse economic spectrum, encompassing both highly developed regions (e.g., Nanchang County, Guixi City, and Gao’an City) and less economically advanced areas. The sample also covered both large grain-producing and non-grain-producing counties, with a range of terrains, including plains and mountainous regions.

Study area. The map was drawn by the author using ArcMap 10.8 software (URL: https://www.arcgis.com/home/index.html).

Our sampling methodology employed a multi-stage stratified random sampling design. First, townships within each sample county were selected using nighttime light data as a proxy for economic development. These townships were stratified into three tiers (high, medium, and low development levels), with one township randomly selected from each tier, yielding three representative townships per county. Subsequently, we implemented a two-stage sampling approach: (1) three villages were randomly selected from each township stratum, and (2) ten farm households were randomly chosen from each selected village. The comprehensive survey instrument captured data at three distinct levels: household production characteristics, individual demographic and labor information, and village-level infrastructure and institutional factors. The questionnaire addressed five key areas: industrial success, ecological sustainability, rural culture, government efficiency, and lifestyle prosperity. A total of 2,160 questionnaires were distributed, and 1,281 rice farmer samples were collected after excluding incomplete responses.

Variable selection

Explained variable

The explained variable in this study is farmers’ adoption of agricultural green production technology. AGPTs refer to a technical system of various skills and rules established for use in agricultural production, aimed at ensuring the quality and safety of agricultural products, promoting modern agrarian development, and maintaining water and soil resources and a healthy environment. In rice cultivation, rational fertilization, scientific irrigation, and pest prevention and control are the keys to ensuring the quality and yield of rice cultivation. Following the Technical Guidelines for Agricultural Green Development (2018–2030) and building upon existing literature57,62,64, this study operationalizes agricultural green production technologies through five representative practices: organic fertilizer application, soil formulation and fertilization, water and fertilizer integration, pest and disease green prevention and control, and water-saving irrigation technology.Farmers’ adoption of the AGPTs was quantified as a count variable (0–5) representing the number of distinct AGPT types implemented.

Core explanatory variable

The core explanatory variable in this study is cooperative membership status. This variable is operationalized through farmers’ cooperative participation using a binary coding scheme (0 = non-participant, 1 = participant). Furthermore, to investigate the differential impacts of cooperative services (pre-production, in-production, post-production) on farmers’ green technology adoption, extended analyses were conducted based on farmers’ access to four specific services: land transfer services, agricultural input procurement services, agricultural production technology services, and agricultural product marketing services. Service accessibility was measured using dichotomous variables (0 = non-recipient, 1 = recipient) for each service category.

Land transfer services constitute pre-production services involving land resource consolidation to establish foundations for large-scale operations. Agricultural input procurement services also fall under pre-production services, enhancing supply chain efficiency through centralized provision of production materials (e.g., seeds and fertilizers) to reduce production costs. Agricultural production technology services operate during in-production phases, providing technical guidance on crop cultivation and plant protection management, directly enhancing quality control and efficiency improvement in production processes. Agricultural product marketing services represent post-production services, achieving product value realization through market connectivity and brand marketing strategies.

Mechanism variables

The study examined four key mechanism variables: environmental awareness, risk attitude, operational scale, and credit accessibility. Environmental awareness serves as the cognitive basis for technology adoption, positively influencing farmers’ adoption intentions through enhanced perception of both ecological benefits and technological utility. Risk attitude is a constraint on behavioral tendency, and risk-preferring farmers are more likely to overcome the uncertainty barriers in technology applications. Operational scale provides support of resource conditions, and moderate-scale business entities have stronger technology absorption capacity and cost-sharing ability. Credit accessibility offers a financial security mechanism, alleviating capital constraints in the adoption process and reducing the threshold of upfront investment in technology applications.

Building on data availability constraints, this study operationalized the mechanism variables through four measurable indicators: farmers’ attitudes toward green production practices, responses to standardized risk attitude assessment items, actual rice cultivation area, and credit accessibility measures. The risk attitude assessment posed the question: “If planting a new crop variety presented three possible outcomes, which would you choose?” Respondents were classified as risk-averse if selecting“ (1) Guaranteed ¥2,000,” risk-neutral if choosing “(2) 50% chance of ¥10,000 or ¥2,000 loss,” and risk-seeking if preferring “(3) 50% chance of ¥20,000 or ¥5000 loss.” This risk attitude classification method is based on the Expected Utility Theory and Prospect Theory65,66,67. We designed choice options with comparable expected values but varying risk levels to distinguish risk preferences. Selection of option (1) (guaranteed ¥2000) indicates risk aversion, demonstrating a preference for certainty over potentially higher but uncertain returns, particularly notable when compared to the risk-neutral option’s implicit expected value of ¥2000. This behavior reflects both the certainty effect and loss aversion. Option (2) represents risk neutrality, where farmers balance expected returns against potential losses without systematic bias toward either risk avoidance or seeking. Option (3) selection identifies risk-seeking behavior, characterized by a willingness to accept greater variance in outcomes for higher potential gains. This approach combines theoretical rigor (rooted in expected utility theory) with practical advantages: intuitive implementation, clear classification of fundamental risk tolerance, and concise measurement.

Control variables

Drawing on existing studies26,38,63, this study incorporated the household head’s individual characteristics, household characteristics, production and management characteristics, village characteristics, and regional characteristics into the model. Among them, individual characteristics include sex, age, health status, educational level, and village cadre status; Household characteristics include the number of laborers and disposable income; Production and management characteristics include the degree of paddy field fragmentation, fertility of paddy fields, and agricultural insurance; Village characteristics include topography and economic development level; The county or city where the household is located is defined as a regional characteristic.

According to Table 1. The mean value of the explained variable is 0.764, indicating a low level of technology adoption among farmers. Only 23.4% of the sample consists of farmers with cooperative membership, reflecting limited engagement in cooperatives. Among the mediating variables, farmers demonstrate a high level of green cognition. However, risk attitude tend to be conservative. The average planting size is slightly more than 2 hm2, and 34.8% of farmers have credit accessibility.

For the control variables, male respondents are predominant, with a mean age of 58 years, generally in good health, and mostly with primary or junior high school education. Few farmers hold village cadre positions. On average, households have slightly more than three family laborers, and disposable income remains below 50,000 yuan. Paddy field fragmentation is high, though fertility is generally good. The villages are predominantly mountainous and hilly, with economies at a medium level.

Analytical content and model construction

Ordered Probit models

Given that the dependent variable—the count of adopted agricultural green production technologies (AGPTs)—represents an ordered discrete variable (range: 0–5) with inherent ordinality, we employ an Ordered Probit model for estimation. This initial analysis phase specifically evaluates the direct effect of cooperative membership on AGPT adoption intensity. The empirical specification is formalized as follows:

where: \(Y_{{\text{i}}}\) is the explained variable; \(X_{{\text{i}}}\) is the core explanatory variable; \(C_{{\text{i}}}\) is the control variable; \(\lambda_{1}\) is a constant term; \(\alpha_{1}\) and \(\beta_{1}\) denotes the regression coefficients; and \(\varepsilon_{{1}}\) is a random disturbance term obeying a normal distribution.

Robustness tests

We will conduct robustness tests to ensure the reliability of the benchmark regression results. First, we redefine farmers’ AGPT as a binary variable and perform regression analysis using the Probit model. This approach aims to test whether the core conclusions depend on the ordered variable assumption and avoid estimation bias caused by the selection of measurement scales. Second, we employ the subsample regression method, conducting regression analysis after excluding samples under 45 and over 65 years old. The rationale is that younger farmers may neglect to adopt agricultural technologies due to a higher propensity for non-farm employment. Older farmers may struggle to implement new technologies due to physical limitations. Excluding these groups can eliminate the interference of age heterogeneity on the core relationship.

Endogeneity tests

Considering the potential self-selection bias and reverse causality in farmers’ participation in cooperatives, this study will conduct endogeneity tests. We address endogeneity issues through propensity score matching (PSM) and two-stage least squares (2SLS). PSM is used to correct self-selection bias, while 2SLS handles reverse causality, ensuring the validity of causal inference in the results.

Extensibility analysis

This study conducts expansion analysis to systematically examine how distinct cooperative services—pre-production (land transfer, input procurement), mid-production (technical guidance), and post-production (marketing support)—influence farmers’ adoption of green production technologies. Moving beyond simplistic membership effects, this granular approach identifies which specific services most effectively drive adoption, enabling targeted optimization of cooperative service portfolios, evidence-based policy interventions, and strategic promotion of sustainable agricultural practices.

Heterogeneity analysis

This study investigates potential heterogeneous effects of cooperative membership on green technology adoption across different farmer subgroups by stratifying the sample based on household heads’ educational attainment and village economic development levels, thereby examining whether the impact varies systematically with human capital endowments and regional socioeconomic contexts. Furthermore, it analyzes technology-specific adoption responses to cooperative participation. These analyses provide empirical evidence to optimize cooperative service systems and develop differentiated promotion policies along three critical dimensions: individual farmer characteristics (human capital), regional development environments, and technology-specific attributes.

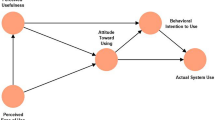

Influence mechanism model

To explore the internal influence mechanism through which cooperative membership affects the adoption of AGPTs, this study constructs a mediation effect model as follows by drawing on relevant literature68,69. The criterion for determining the mediation effect is that if, after including both the core explanatory variable and the mediating variable in the regression model, the regression coefficient of the mediating variable is statistically significant, and the regression coefficient of the core explanatory variable decreases further compared to the benchmark regression results, this indicates the presence of a “mediation effect”.

where: \(M_{{\text{i}}}\) is the mechanism variables; \(X_{{\text{i}}}\) is the core explanatory variable; \(C_{{\text{i}}}\) is the control variables; \(\lambda_{{2}}\), \(\lambda_{{3}}\) is a constant term; \(\alpha_{{2}}\), \(\beta_{{2}}\), \(c^{\prime}\), \(b\), \(g_{3}\), denotes the regression coefficients; and \(\varepsilon_{{2}}\), \(\varepsilon_{{3}}\) is a random disturbance term obeying a normal distribution. Additionally, the coefficient \(c^{\prime}\) also represents the direct effect of the core explanatory variable on the explained variable. The indirect effect of the core explanatory variable on the explained variable is equal to the product of coefficients \(\alpha_{{2}}\) and \(b\). The total effect of the core explanatory variable is equal to the sum of its direct effect and indirect effect.

Results and discussion

Benchmark regression analysis

Given the possible covariance problem among the variables, this study conducted a covariance diagnosis before regression analysis. The variance inflation factor (VIF) diagnostics revealed a maximum value of 1.44 and mean value of 1.15 across all explanatory variables, with all values substantially below the conventional threshold of 10, thereby confirming the absence of multicollinearity concerns in our empirical specification. This study used Stata17 software to examine the impact of cooperative membership on technology adoption behavior using a multivariate ordered probit model, and the findings are shown in Table 2.

Impact of core explanatory variables

As shown in Model 1, the coefficient for cooperative membership is positive and meets the 1% significance level, suggesting that cooperative membership significantly encourages farmers to adopt AGPTs. These results align with those reported by Lei et al. (2024)27 and Yu et al. (2021)28, verifying Hypothesis 1.

The likely explanation is that cooperatives offer services that lower the barriers to technology adoption. Through publicity, training, and member demonstrations, cooperatives deepen farmers’ comprehension of green technologies, augmenting their propensity to embrace them. Additionally, cooperative membership improves farmers’ market negotiating power, reducing the economic constraints associated with technology adoption and making these technologies more accessible.

Effects of control variables

Farmers’ health status, education level, number of family laborers, degree of paddy field fragmentation, field fertility, and village economic development all showed statistical significance. The influence of health status on the utilization of technology was favorable at the 10% significance level. Good health provides the foundation for farmers to engage in agricultural activities and adopt new technologies. Better health increases their capacity to participate in productive activities.

Education level positively influences technology adoption at the 1% significance level. Farmers with greater literacy have stronger learning capabilities and knowledge, enabling them to acquire, apply, and understand the value of technology in boosting agricultural income12. A larger number of family laborers increases the likelihood of technology adoption, as rice cultivation is labor-intensive and requires significant workforce input for planting, fertilization, breeding, and harvesting17.

Conversely, higher paddy field fragmentation reduces the likelihood of technology adoption. Fragmentation increases labor intensity, raises associated costs, and may create a “broken window” effect, discouraging farmers from using green technologies70. Better field fertility encourages technology use, as farmers are more inclined to maintain high fertility levels to ensure consistent yields57.

Finally, village economic development significantly promotes the adoption of green technologies. Higher economic development levels improve farmers’ understanding of these technologies, increasing their motivation to adopt them.

Robustness test analysis

Replacing the explained variable

This study redefined farmers’ adoption of green production technologies as a binary variable and performed regression analysis using a Probit model. As shown in Model 2, after replacing the variable for regression analysis, cooperative membership still has a positive and significant effect on farmers’ adoption of AGPTs (Table 2). In summary, the robustness check is valid.

Subsample regression method

Considering the sample data and the current situation in rural areas, this study excludes samples of individuals under 45 years old and over 65 years old before conducting regression analysis on the remaining samples. Cooperative participation remains statistically significant at the 1% level with a positive direction (Model 3), indicating robust baseline regression results.

Endogeneity test analysis

The previous benchmark regression verified that cooperative membership could greatly enhance farmers’ utilization of technologies. However, the potential endogeneity problem between the two was neglected, which might potentially result in inaccuracies in the outcomes of the benchmark regression. Therefore, this study will further explore the endogeneity issue to guarantee the dependability of the research analysis.

Self-selection bias

Potential self-selection bias in farmers’ cooperative participation may introduce endogeneity concerns. To address this, we employ propensity score matching (PSM), a well-established method for correcting selection bias. Our analysis divides the sample into: (1) a treatment group (cooperative members) and (2) a control group (non-members), then estimates the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) by comparing mean differences in entrepreneurial behaviors between matched pairs. This approach robustly isolates the causal effect of cooperative membership while controlling for observable confounding factors.

The results in Table 3 indicate that farmers engaged in cooperatives are more inclined to use AGPTs. The ATT values after nearest neighbor matching, kernel matching, and radius matching are 0.303, 0.328, and 0.325, respectively, which satisfy the significance test, demonstrating the reliability of the prior benchmark regression analysis findings.

Mutual causation

While the initial findings demonstrate a significant positive association between cooperative membership and farmers’ adoption of agricultural green production technologies (AGPTs), potential endogeneity due to reverse causality necessitates further examination. Following established empirical approaches61, we employ the county-level cooperative participation rate (excluding the focal farmer) as an instrumental variable (IV) and implement a two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimation strategy. The IV satisfies both relevance and exclusion conditions: (1) Relevance is grounded in social learning theory, whereby regional peer effects significantly influence individual participation decisions; (2) Exogeneity is maintained as county-level participation rates affect individual technology adoption only through their own cooperative membership. Diagnostic tests confirm the instrument’s validity, supporting the robustness of our causal inference.

According to Table 4. The results of the Hausman test suggest that cooperative participation cannot be treated as an exogenous variable, necessitating an endogeneity test. In the first-stage regression, county-level cooperative participation rate significantly increases the likelihood of cooperative participation. The F-statistic for the joint significance of the instrumental variables is 16.741, exceeding the empirical safety threshold of 10. This rejects the null hypothesis of weak instruments and confirms the validity of the selected instrumental variables.

In the second-stage regression, cooperative membership positively influences farmers’ utilization of green technologies. This supports the reliability of the results in Table 2. After addressing potential endogeneity using the instrumental variable approach, cooperative membership greatly enhances the probability of green technology adoption.

Extensibility analysis

Impact of cooperative services on farmers’ green production technology adoption behavior

Farmers benefit from various services provided by cooperatives throughout the production process. Focusing solely on the effect of cooperative membership on the utilization of AGPTs may overlook the broader influence of specific services. Therefore, this research explores how land transfer, agricultural input procurement, agricultural production technology, and agricultural product marketing services cooperatives provide affect farmers’ utilization of AGPTs.

As shown in Table 5, these services substantially facilitate the implementation of green technologies. Land transfer services allow farmers to scale up operations, reducing technology adoption costs through economies of scale. Agricultural procurement services increase technology accessibility and lower input and transaction costs. Production technology services enhance farmers’ technical knowledge, reducing the perceived complexity of new technologies. Additionally, marketing services impose quality standards, encouraging the use of green technologies. These services also help farmers achieve better product quality and prices, increasing income prospects and boosting confidence in adopting green practices.

Heterogeneity analysis

Although cooperative membership may greatly facilitate farmers’ acceptance of green technologies, the effect of cooperative membership on farmers’ adoption of green technologies may differ depending on individual characteristics and the region’s economic development level. Therefore, to obtain more detailed conclusions, this study grouped the samples by two dimensions: the head of the household’s educational level and the village’s economic development level.

Heterogeneity analysis of education levels

This research categorized the household head’s educational attainment into two groups: a high-education group (high school and above) and a low-education group (below high school). Compared with the high-education group, the influence of cooperative membership on the utilization behavior of green technology of low-educated residents is more prominent (Table 6), which contradicts the conclusions derived by Liu et al. (2022)39 but consistent with the findings of the study by Abebaw and Haile (2013)26. The possible reason for this is that low-educated residents have poorer learning and acceptance ability, and have limited resource endowment, so they need the help and drive of cooperatives. Hence, the possibility of using technology is greater after low-educated residents participate in cooperatives.

Heterogeneity analysis of the level of economic development of villages

This research classified villages into two groups according to economic development: low (below midstream) and high (midstream and above). The influence of cooperative membership on technology adoption is more significant in villages with elevated economic development levels (Table 8), which contrasts with the findings of Abebaw and Haile (2013)26. The likely reason is that farmers in more developed villages benefit from better production conditions and resources, and are more focused on ecological protection and sustainable development. Additionally, cooperatives in these areas may be better equipped to provide information and advice on green technologies, helping farmers learn and apply these practices more effectively.

Impact of cooperative membership on the adoption behavior of various AGPTs

Cooperative membership substantially enhances farmers’ use of green technologies, but its effect varies across different technologies. As shown in Table 7, cooperative participation promotes farmers to adopt organic fertilizer application, soil-formula fertilization, water-fertilizer integration, and green pest control technologies. However, it does not significantly impact the use of water-saving irrigation technology.

The analysis reveals no statistically significant effect of cooperative membership on the adoption of water-saving irrigation technology. This null finding may be attributable to two key factors: First, the low adoption prevalence (n = 77 households in our sample) suggests limited farmer prioritization of this technology, potentially reflecting inadequate policy incentives8. Second, comparative analysis indicates that unlike relatively simple irrigation technologies, fertilizer application and pest control require more sophisticated agronomic knowledge, making farmers more dependent on cooperatives for technical training and operational support. This contrast highlights the critical role of cooperatives in building complex agricultural competencies rather than facilitating simpler technological adoptions.

Analysis of impact mechanisms

According to prior theoretical analysis, cooperative membership influences farmers’ adoption of AGPTs through four pathways: enhancing environmental awareness, risk attitude, operational scale, and credit accessibility. This study tests these pathways using a mediation effect model, with results shown in Table 8.

Models 20, 22, 24, and 26 show that cooperative membership significantly enhances green perception, risk attitude, operational scale, and credit access. In Models 21, 23, 25, and 27, the above four variables and cooperative membership jointly positively impact farmers’ green technology adoption, and the coefficient of the core independent variable is smaller than the benchmark regression results (0.303). Meanwhile, this study further reports the direct effects, indirect effects, and total effects. As shown in Table 9, Models 28, 29, 30, and 31 report the effect coefficients related to environmental awareness, risk attitude, operational scale, and credit accessibility, respectively. It can be seen that the indirect effect coefficients of cooperative membership on technology adoption behavior through environmental awareness, risk attitude, operational scale, and credit accessibility are positive and significant, indicating that cooperative membership enhances farmers’ environmental awareness, risk attitude, operational scale, and credit accessibility, thereby promoting farmers to adopt green technologies. The mediating effect coefficients of the above mechanism variables are 0.017, 0.014, 0.013, and 0.015, respectively, and it is further found that the proportions of mediating effects in total effects are 5.6%, 4.6%, 4.3%, and 5.0%, respectively. Thus, Hypotheses 2, 3, 4, and 5 are supported.

In summary, from an internal perspective, cooperatives boost farmers’ intrinsic motivation to adopt green technology by increasing awareness of green production and risk tolerance. Externally, cooperatives help farmers overcome practical challenges, such as limited scale efficiency and capital constraints, consequently boosting their use of green technologies.

Conclusions and recommendations

Conclusion

This study provides new theoretical perspectives and practical insights for agricultural sustainable development by empirically analyzing the influence mechanism of cooperative membership on farmers’ adoption of AGPTs. Theoretically, it constructs a multidimensional mechanism analysis framework for how cooperative membership affects farmers’ adoption of green production technologies, integrating internal and external factors such as environmental awareness, risk attitude, operational scale, and credit accessibility into a unified analytical system. This breaks through the limitations of the single perspective in traditional research and provides a new theoretical paradigm for understanding the interactive relationship between agricultural organizational innovation and technology adoption behavior. Practically, the study reveals the key role of cooperatives in overcoming the green transformation dilemma of smallholder farmers, especially the differentiated impacts on farmers with lower education levels and in economically developed villages, providing an empirical basis for the precise design of agricultural policies. The findings not only offer a feasible path for China to advance its strategies for green agrarian development and rural revitalization but also offer valuable references for developing countries worldwide to promote sustainable agricultural transformation through cooperative economic organizations, contributing to the construction of a more resilient agricultural production system and an environmentally friendly development model.

Based on an analysis of survey data from 1281 rice growers in Jiangxi Province, this study uses a multivariate ordered Probit model and a mediation effect model to examine the impact of cooperative membership on farmers’ adoption of AGPTs, drawing the following conclusions: First, cooperative membership significantly increases the likelihood of farmers adopting AGPTs, and the results remain robust after passing robustness and endogeneity tests. Second, the cooperative’s land transfer services, agricultural input procurement, agricultural production technology, and agricultural product marketing services encourage farmers to adopt green production technologies. Third, cooperative membership is more effective in promoting farmers with lower education levels and those in villages with higher economic levels to adopt green production technologies actively. Cooperative membership also encourages farmers to adopt organic fertilizer application technology, soil testing and formula fertilization technology, water-fertilizer integration technology, and green pest control technology. Still, it has no significant effect on adopting water-saving irrigation technology. Fourth, environmental awareness, risk attitude, operational scale, and credit accessibility partially mediate between cooperative membership and farmers’ adoption of AGPTs.

Recommendations

According to the results, this research offers several recommendations:

First, as cooperative membership significantly boosts farmers’ enthusiasm for adopting green technologies, the government should prioritize support for developing farmers’ cooperatives. Emphasis should be placed on standardizing cooperatives and enhancing services such as land transfer, agricultural procurement, technical training, and product marketing. Encouraging more farmers to join cooperatives can foster a sense of participation and organizational identity, ultimately strengthening farmers’ capacity to adopt green technologies.

Second, recognizing the heterogeneous effects of cooperative membership across farmer demographics and technology types, policymakers should implement differentiated interventions: (1) For less-educated farmers, structured training programs with hands-on demonstrations can overcome cognitive barriers to adoption; (2) Economically disadvantaged villages should leverage cooperatives as sustainability hubs through local champion farmers; (3) Advanced villages should scale best practices via model cooperatives that demonstrate operational efficiency and facilitate peer learning. To specifically address low water-saving irrigation uptake, targeted cost-share programs (covering 30–50% of installation expenses) coupled with performance-based incentives would effectively reduce adoption barriers while ensuring technology utilization.

Finally,To leverage the mediating roles of environmental awareness, risk attitude, operational scale, and credit accessibility in the cooperative-technology adoption nexus, a dual-pronged strategy is recommended: Internally, cooperatives should (1) implement monthly sustainability education programs to strengthen ecological consciousness, (2) develop comprehensive risk management packages combining yield insurance, forward contracts, and profit-sharing schemes to mitigate production uncertainties, and (3) conduct hands-on technical workshops to build practical skills; externally, they should (a) establish streamlined land consolidation services to enable scale economies, (b) advocate for targeted subsidy policies to lower adoption costs, and (c) forge institutional partnerships with rural banks and microfinance providers to develop innovative credit products tailored to green technology investments, thereby addressing both cognitive and structural barriers to sustainable agricultural transformation.

Limitations and outlook of the study

Although this paper verifies that cooperative membership can promote green technology adoption among farmers, it still has the following limitations. On the one hand, this study used cross-sectional data for analysis, which has limitations in dynamic effect analysis and other aspects. Future research could select longitudinal farmer tracking data for analysis. On the other hand, this study only used the number of farmers’ adoption to characterize their green production technology adoption behaviors, which may have overlooked the differences in regional applicability, functions, attributes, and effects of each technology, and future studies could use more scientific methods to measure the level of farmers’ use of green technologies.

Data availability

The raw data and analysis files used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Liu, Y., Pan, X. & Li, J. A 1961–2010 record of fertilizer use, pesticide application and cereal yields: a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35, 83–93 (2015).

Carvalho, F. P. Pesticides, environment, and food safety. Food Energy Secur. 6, 48–60 (2017).

Lal, R. Restoring soil quality to mitigate soil degradation. Sustainability 7, 5875–5895 (2015).

Islam, S. M. M. et al. Mitigating greenhouse gas emissions from irrigated rice cultivation through improved fertilizer and water management. J. Environ. Manage. 307, 114520 (2022).

Naher, U. A. et al. Bio-organic fertilizer: a green technology to reduce synthetic N and P fertilizer for rice production. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 602052 (2021).

Farooq, M. S. et al. Partial replacement of inorganic fertilizer with organic inputs for enhanced nitrogen use efficiency, grain yield, and decreased nitrogen losses under rice-based systems of mid-latitudes. BMC Plant Biol. 24, 919 (2024).

Han, H., Zou, K. & Yuan, Z. Capital endowments and adoption of agricultural green production technologies in China: a meta-regression analysis review. Sci. Total Environ. 897, 165175 (2023).

Dong, C., Wang, H., Long, W., Ma, J. & Cui, Y. Can agricultural cooperatives promote chinese farmers’ adoption of green technologies?. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 20, 4051 (2023).

Asiedu-Ayeh, L. O., Zheng, X., Agbodah, K., Dogbe, B. S. & Darko, A. P. Promoting the adoption of agricultural green production technologies for sustainable farming: a multi-attribute decision analysis. Sustainability 14, 9977 (2022).

Dar, M. H. et al. Gender focused training and knowledge enhances the adoption of climate resilient seeds. Technol. Soc. 63, 101388 (2020).

Adnan, N., Nordin, S. M., Bahruddin, M. A. & Tareq, A. H. A state-of-the-art review on facilitating sustainable agriculture through green fertilizer technology adoption: assessing farmers behavior. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 86, 439–452 (2019).

Zou, Q., Zhang, Z., Yi, X. & Yin, C. The direction of promoting smallholders’ adoption of agricultural green production technologies in China. J. Clean. Prod. 415, 137734 (2023).

Mao, H., Zhou, L., Ying, R. & Pan, D. Time Preferences and green agricultural technology adoption: Field evidence from rice farmers in China. Land Use Policy 109, 105627 (2021).

Wang, Y., He, K., Zhang, J. & Chang, H. Environmental knowledge, risk attitude, and households’ willingness to accept compensation for the application of degradable agricultural mulch film: Evidence from rural China. Sci. Total Environ. 744, 140616 (2020).

Li, W. et al. Gap between knowledge and action: understanding the consistency of farmers’ ecological cognition and green production behavior in Hainan Province. China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-024-04464-1 (2024).

Li, C., Shi, Y., Khan, S. U. & Zhao, M. Research on the impact of agricultural green production on farmers’ technical efficiency: evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 38535–38551 (2021).

Huang, X., Lu, Q., Wang, L., Cui, M. & Yang, F. Does aging and off-farm employment hinder farmers’ adoption behavior of soil and water conservation technology in the Loess Plateau?. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 12, 92–107 (2020).

Ren, Z., Fu, Z. & Zhong, K. The influence of social capital on farmers’ green control technology adoption behavior. Front. Psychol. 13, 1001442 (2022).

Wei, T., Liu, Y., Wang, K. & Zhang, Q. Can crop insurance encourage farmers to adopt environmentally friendly agricultural technology—the evidence from Shandong Province in China. Sustainability 13, 13843 (2021).

Sun, X., Lyu, J. & Ge, C. Knowledge and farmers’ adoption of green production technologies: an empirical study on IPM adoption intention in major indica-rice-producing areas in the Anhui Province of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, 14292 (2022).

Chi, L., Han, S., Huan, M., Li, Y. & Liu, J. Land fragmentation, technology adoption and chemical fertilizer application: evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, 8147 (2022).

Dessart, F. J., Barreiro-Hurlé, J. & Van Bavel, R. Behavioural factors affecting the adoption of sustainable farming practices: a policy-oriented review. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 46, 417–471 (2019).

Zhu, Z., Chen, Y., Ning, K. & Liu, Z. Policy setting, heterogeneous scale, and willingness to adopt green production behavior: field evidence from cooperatives in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26, 1529–1555 (2022).

Wang, H., Wang, X., Sarkar, A. & Zhang, F. How capital endowment and ecological cognition affect environment-friendly technology adoption: a case of apple farmers of Shandong Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 18, 7571 (2021).

Li, M., Wang, J., Zhao, P., Chen, K. & Wu, L. Factors affecting the willingness of agricultural green production from the perspective of farmers’ perceptions. Sci. Total Environ. 738, 140289 (2020).

Abebaw, D. & Haile, M. G. The impact of cooperatives on agricultural technology adoption: Empirical evidence from Ethiopia. Food Policy 38, 82–91 (2013).

Lei, L. et al. Research on the influence of education and training of farmers’ professional cooperatives on the willingness of members to green production—perspectives based on time, method and content elements. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26, 987–1006 (2024).

Yu, L. et al. Risk aversion, cooperative membership and the adoption of green control techniques: evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 279, 123288 (2021).

Li, H., Liu, Y., Zhao, X., Zhang, L. & Yuan, K. Estimating effects of cooperative membership on farmers’ safe production behaviors: evidence from the rice sector in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 25400–25418 (2021).

Zhang, S., Sun, Z., Ma, W. & Valentinov, V. The effect of cooperative membership on agricultural technology adoption in Sichuan, China. China Econ. Rev. 62, 101334 (2020).

Luo, L. et al. Research on the influence of education of farmers’ cooperatives on the adoption of green prevention and control technologies by members: evidence from rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, 6255 (2022).

Li, D., Dang, H. & Yu, J. Can participation in cooperatives promote the adoption of green production techniques by Chinese apple growers: counterfactual estimation based on propensity score matching. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1026273 (2022).

Li, C., Deng, H., Yu, G., Kong, R. & Liu, J. Impact effects of cooperative participation on the adoption behavior of green production technologies by cotton farmers and the driving mechanisms. Agriculture 14, 213 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. The effect of technical training provided by agricultural cooperatives on farmers’ adoption of organic fertilizers in china: based on the mediation role of ability and perception. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, 14277 (2022).

Adnan, N., Md-Nordin, S., Rahman, I. & Noor, A. Adoption of green fertilizer technology among paddy farmers: a possible solution for Malaysian food security. Land Use Policy 63, 38–52 (2017).

Neupane, H., Paudel, K. P., Adhikari, M. & He, Q. Impact of cooperative membership on production efficiency of smallholder goat farmers in nepal. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 93, 337–356 (2022).

Manda, J. et al. Does cooperative membership increase and accelerate agricultural technology adoption? empirical evidence from Zambia. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 158, 120160 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Lu, Q., Yang, C. & Grant, M. K. Cooperative membership, service provision, and the adoption of green control techniques: evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 384, 135462 (2023).

Liu, Y., Shi, R., Peng, Y., Wang, W. & Fu, X. Impacts of technology training provided by agricultural cooperatives on farmers’ adoption of biopesticides in China. Agriculture 12, 316 (2022).

Tang, L., Liu, Q., Yang, W. & Wang, J. Do agricultural services contribute to cost saving? Evidence from Chinese rice farmers. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 10, 323–337 (2018).

Zhong, Z., Jia, F., Long, W. & Chen, K. Z. Risk sharing, benefit distribution and cooperation longevity: sustainable development of dairy farmer cooperatives in China. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 20, 982–997 (2022).

Li, Y., Fan, Z., Jiang, G. & Quan, Z. Addressing the differences in farmers’ willingness and behavior regarding developing green agriculture—a case study in Xichuan County, China. Land 10, 316 (2021).

Luo, L. et al. Training of farmers’ cooperatives, value perception and members’ willingness of green production. Agriculture 12, 1145 (2022).

Gao, R., Zhang, H., Gong, C. & Wu, Z. The role of farmers’ green values in creation of green innovative intention and green technology adoption behavior: evidence from farmers grain green production. Front. Psychol. 13, 980570 (2022).

Yu, L. et al. Assessing influence mechanism of green utilization of agricultural wastes in five provinces of china through farmers’ motivation-cognition-behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 17, 3381 (2020).

Komarek, A. M., De Pinto, A. & Smith, V. H. A review of types of risks in agriculture: What we know and what we need to know. Agric. Syst. 178, 102738 (2020).

Tong, Q., Swallow, B., Zhang, L. & Zhang, J. The roles of risk aversion and climate-smart agriculture in climate risk management: evidence from rice production in the Jianghan Plain, China. Clim. Risk Manag. 26, 100199 (2019).

Menapace, L., Colson, G. & Raffaelli, R. Risk aversion, subjective beliefs, and farmer risk management strategies. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 95, 384–389 (2013).

Molla, A., Beuving, J. & Ruben, R. Risk aversion, cooperative membership, and path dependences of smallholder farmers in Ethiopia. Rev. Dev. Econ. 24, 167–187 (2020).

Shi, Y. & Wang, F. Revenue and risk sharing mechanism design in agriculture supply chains considering the participation of agricultural cooperatives. Systems 11, 423 (2023).

Van Winsen, F. et al. Determinants of risk behaviour: effects of perceived risks and risk attitude on farmer’s adoption of risk management strategies. J. Risk Res. 19, 56–78 (2016).

Liu, E. M. Time to change what to sow: risk preferences and technology adoption decisions of cotton farmers in China. Rev. Econ. Stat. 95, 1386–1403 (2013).

Mao, H., Quan, Y. & Fu, Y. Risk preferences and the low-carbon agricultural technology adoption: evidence from rice production in China. J. Integr. Agric. 22, 2577–2590 (2023).

Liu, Q. & Yan, T. The effect of noncognitive abilities on promoting the adoption of soil testing and formula fertilization technology by farmers: empirical insights from Central China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-04109-9 (2023).

Liu, Z., Rommel, J., Feng, S. & Hanisch, M. Can land transfer through land cooperatives foster off-farm employment in China?. China Econ. Rev. 45, 35–44 (2017).

Li, J., Feng, S., Luo, T. & Guan, Z. What drives the adoption of sustainable production technology? Evidence from the large scale farming sector in East China. J. Clean. Prod. 257, 120611 (2020).

Sui, Y. & Gao, Q. Farmers’ endowments, technology perception and green production technology adoption behavior. Sustainability 15, 7385 (2023).

Slamet, A., Nakayasu, A. & Ichikawa, M. Small-scale vegetable farmers’ participation in modern retail market channels in indonesia: the determinants of and effects on their income. Agriculture 7, 11 (2017).

Peng, Y., Wang, H. H. & Zhou, Y. Can cooperatives help commercial farms to access credit in China? Evidence from Jiangsu Province. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. Agroecon. 70, 325–349 (2022).

Jiang, M., Li, J. & Mi, Y. Farmers’ cooperatives and smallholder farmers’ access to credit: evidence from China. J. Asian Econ. 92, 101746 (2024).

Yu, L., Nilsson, J., Zhan, F. & Cheng, S. Social capital in cooperative memberships and farmers’ access to bank credit-evidence from Fujian, China. Agriculture 13, 418 (2023).

Zuo, Z. P. Environmental regulation, green credit, and farmers’ adoption of agricultural green production technology based on the perspective of tripartite evolutionary game. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1268504 (2023).

Yu, L., Zhao, D., Xue, Z. & Gao, Y. Research on the use of digital finance and the adoption of green control techniques by family farms in China. Technol. Soc. 62, 101323 (2020).

Qing, C., Zhou, W., Song, J., Deng, X. & Xu, D. Impact of outsourced machinery services on farmers’ green production behavior: evidence from Chinese rice farmers. J. Environ. Manage. 327, 116843 (2023).

Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. In Handbook of the Fundamentals of Financial Decision Making, vol. 4 99–127 (World Scientific, 2012).

Holt, C. A. & Laury, S. K. Risk aversion and incentive effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 92, 1644–1655 (2002).

Mao, H. & Fu, Y. Risk preference and relative poverty: an analysis based on the data of China family panel studies. Econ. Anal. Policy 82, 220–232 (2024).

Baron, R. M. & Kenny, D. A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182 (1986).

Mulungu, K., Manning, D. T. & Bozzola, M. Once bitten, twice shy? Direct and indirect effects of weather shocks on fertilizer and improved seeds use. Food Policy 133, 102852 (2025).

Zhang, J., Chen, M., Huang, C. & Lai, Z. Labor endowment, cultivated land fragmentation, and ecological farming adoption strategies among farmers in Jiangxi Province, China. Land 11, 679 (2022).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Jiangxi Provincial Key Laboratory of Conservation Biology (No. 2023SSY02081), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72263017, No. 71934003), the Jiangxi Provincial Forestry Bureau (Innovation Special Project [2023] No. 9), the Major Social Science Projects of Jiangxi Province (No.23ZK07).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.; methodology, C.C. and F.Y.; software, R.P.; validation, C.C., F.Y. and W.L.; formal analysis, R.P.; investigation, C.C.; resources, W.L.; data curation, F.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.; writing—review and editing, W.L.; visualization, R.P.; supervision, F.Y.; project administration, F.Y.; funding acquisition, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols were approved by the Jiangxi Agricultural University. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, C., Peng, R., Ye, F. et al. The role of cooperative membership in promoting agricultural green production technologies among rice farmers in rural China. Sci Rep 15, 31044 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09181-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09181-x