Abstract

Understanding individual differences in cognitive reserve is key to predicting, and potentially influencing, factors that promote healthy cognitive aging. It has been suggested that individuals who are more curious engage in more stimulating activities and thereby increase their cognitive reserve. In the present study, we investigated the relationships between dimensions of trait curiosity and different proxies of cognitive reserve - education, occupation, and leisure activities - in groups of younger (N = 190) and middle-to-older aged adults (N = 292). Our results provide evidence for a relationship between trait curiosity and cognitive reserve, which was more pronounced in middle-to-older age. In the middle-to-older age group, all proxies of cognitive reserve were related to curiosity, albeit to different dimensions of the trait: higher interest-based epistemic curiosity and perceptual curiosity predicted higher education and leisure activities. In contrast, deprivation-sensitive curiosity was positively associated with occupation, but negatively associated with leisure. In the young group, only leisure activities were significantly predicted by perceptual curiosity. This study adds to the emerging literature on the role of personality in cognitive reserve and highlights the multifaceted influence of trait curiosity, which is larger in older age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Curiosity is considered an intrinsic desire to acquire new information, experience, knowledge, and comprehension1,2,3,4. While curiosity may be elicited as a temporary state triggered by a specific situation or stimulus, curiosity is also an enduring trait that influences how a person approaches and engages with the world around them5,6,7. Individuals with high trait curiosity strive for exploring and understanding their environment, which is intrinsically rewarding to them. High trait curiosity may manifest in different ways, such as a preference for intellectual challenges, an interest in novelty and complexity, and social engagement.

Trait curiosity is a multidimensional construct6,8,9,10,11. One distinction has been made between perceptual curiosity, the urge for novel or surprising sensory experiences and resolving perceptual uncertainties, and epistemic curiosity, the desire to acquire new knowledge or understanding. Perceptual curiosity is more immediate and may be triggered by seeing something unfamiliar, hearing a strange sound, or encountering a new texture or taste12. By contrast, epistemic curiosity is driven by the goal of filling knowledge gaps by learning new information and may be elicited by intellectual challenges, prompting the individual to seek explanations, facts, or solutions. Thus, epistemic curiosity is often associated with more sustained and long-term learning pursuits. Within the concept of epistemic curiosity, a further differentiation has been made between deprivation-sensitive (D-Type) and interest-based (I-Type) epistemic curiosity13,14. D-Type epistemic curiosity arises from a need to fill a knowledge gap, associated with dissatisfaction due to unknowingness. I-Type epistemic curiosity, by contrast, is driven by a genuine interest in knowledge gain and the wish to explore, learn, and discover, without any pressing need to know. Most scales measuring trait curiosity sort into the interest and deprivation dimensions, and expressions of these trait dimensions are, while correlated, related to different kinds of knowledge seeking1,15. Trait curiosity is also related to, and sometimes considered a facet of, the global Big Five personality factor ‘openness to experience’16. However, curiosity is focused on the active pursuit of knowledge and experience, whereas openness is a broader trait that also captures behaviors and attitudes related to intellectuality, creativity, and open-mindedness17. Furthermore, dimensions of curiosity are differently related to the other Big Five personality traits. While interest-based epistemic curiosity is more strongly associated with openness and extraversion, deprivation-sensitive epistemic curiosity is more strongly associated with conscientiousness18.

Recent research shows that personality traits are meaningfully related to both cognitive reserve and cognitive functioning19,20,21,22. Notably, higher expressions of the Big Five traits related to aspects of curiosity, openness to experience and conscientiousness, are most consistently associated with better cognitive outcomes and less age-related cognitive decline, likely due to their connections with intellectual engagement and health-promoting behaviors19,23. While conscientiousness tends to increase from young to middle-age24there is evidence that openness to experience and related traits decline with age25,26,27. Correspondingly, higher levels of curiosity have been suggested to be protective against age-related decline in cognitive performance28. More specifically, by increasing exposure to cognitively stimulating environments and experiences, higher levels of curiosity may contribute to building up cognitive reserve (CR)28,29,30. CR refers to the brain’s ability to cope with age-related changes or damage, helping individuals to maintain cognitive functions despite neurological challenges31,32. Cognitively challenging experiences across the entire adult lifespan are assumed to contribute to the build-up of CR. This theoretical framework has been supported by studies demonstrating that preserved cognitive functions in older age are associated with higher levels of education, challenging professions, and extraprofessional cognitive and social engagement. Accordingly, educational level, occupational status, and leisure activities are the most commonly used proxy measures of CR33,34,35.

Some recent evidence suggests that a higher expression of trait curiosity may indeed be related to a higher CR. Specifically, openness is the personality trait has most robustly been related to cognitive performance and preserved cognitive functioning in older age21,36,37,38although not always39. Furthermore, small to moderate relationships between openness and CR have recently been reported in older adults40. CR in this study was measured using the CoRe-T34which uses self-report data on education, occupation, and leisure activities, as well as two tasks to assess fluidity of thought. The relationship between CR and Openness was found to be higher for the self-report score than the fluidity score of the CoRe-T. Presumably, aspects of curiosity, related to openness, positively influence CR by facilitating different reserve-promoting behaviors reflected in the self-reported proxy measures of CR. A further differentiation between the proxy measures education, occupation, and leisure activities, however, was not reported in this study.

Notably, although trait curiosity has been suggested to shape experiences across the lifespan41most studies that have examined the relationships between trait curiosity and different reserve-promoting factors, did so in younger individuals. In young adulthood, greater curiosity has been related to better academic and job performance42,43,44. Furthermore, curiosity was shown to predict well-being and life satisfaction, which was suggested to result from curious individuals being motivated to initiate new behaviors and choose activities that expand their skills, learning potential, and experiences44,45. These benefits of curiosity demonstrated in young adulthood may persist, or even increase, in older age, thereby contributing to CR. However, the relationships between different dimensions of trait curiosity and proxies of CR have not yet been systematically investigated across adult age groups. Presumably, associations between trait curiosity and CR may be different in young and older adulthood. CR reflects accumulated education, professional experience, and leisure pursuits—factors that typically broaden and solidify by midlife and into older adulthood. CR accrues differently over time across the three subdomains46 and, for younger adults, many of these lifelong experiences have not yet fully accrued. Thus, CR measured in young adulthood only captures immediate or short-term engagement in cognitively stimulating activities. From about age 50 onward, individuals have usually reached stable educational and career levels and have had more opportunities for sustained engagement in leisure and learning activities, making CR scores a more robust reflection of lifetime cognitive engagement.

The goal of the present study was to examine the relationship between facets of trait curiosity and CR directly in a young (18–30 years) and a middle-to-older aged (50–78 years) healthy sample (N = 482). Curiosity and CR were assessed via an online survey. We focused on the curiosity dimensions proposed by Litman and colleagues: I-Type and D-Type epistemic curiosity13 and perceptual curiosity12. We used a short online version of the widely used CR index questionnaire (CRIq)33,47,48in which CR is subdivided into separate scores for education, work, and leisure activities35,49. Our main hypothesis was that higher trait curiosity would be related to higher CR. Furthermore, we expected that this positive relationship would be stronger in the group of middle-to-older aged participants than in young participants, as the influence of curiosity-driven, self-motivated behavior may increase over the adult lifespan28. Finally, we explored whether different dimensions of curiosity are differently associated with subdomains of CR. Such relationships between personality and different proxy measures of CR have not been systematically investigated, yet.

Method

Participants and data collection

We combined data from five online studies conducted at the Donders Center for Cognition between September 2023 and September 2024, in which trait curiosity and CR were assessed in adults of a broad age range (18–78 years). Additional experimental and/or survey data were assessed in each study, of which the results will be reported elsewhere. Four studies included visual search experiments, with the aim to investigate age differences in various task performance measures. The experiments were comparable in terms of difficulty and duration (30–40 min). These experiments were pre-registered (1), Oct 2023: https://osf.io/2rgwq, 2), March 2024: https://osf.io/cp5dr; 3), April 2024: https://osf.io/zds73; 5), Sep 2024: https://osf.io/ehrk9); with some also registering exploratory analyses on cognitive reserve and curiosity measures. One study included multiple surveys and a cognitive test (digit span). This study was a student research project and was not preregistered.

The participants received a link to the respective study via Prolific or Gorilla and provided consent to participate in the study before any data was collected. The studies were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and national and institutional ethical guidelines. The studies were ethically approved by the local ethical committee of the Faculty of Social Sciences, Radboud University (ECSW-LT-2022-4-25-53422, ECSW-LT-2024-4-23-17118, ECSW-LT-2023-7-11-67909, ECSW-LT-2024-4-15-69818).

Three out of the five studies included data of a younger sample (18–30 years) and an older sample (50 + years). One study included participants from a continuous age range (40–78 years). One study included only middle to older-aged individuals (50+). From the initial sample, we excluded 44 participants aged 31–49 years, as we had relatively few participants within this middle-age range (compared to the age ranges of 18–30 and 50+), due to the different selection age-criteria of the included studies. Furthermore, 132 participants with incomplete data, and 20 duplicate answers from participants who took part in more than one of these studies. Most exclusions due to incomplete data resulted from incomplete or unreliable answers in the s-CRIq (see more information below). Three participants were excluded from the CRI-Education calculation, 67 from CRI-Work, and 42 participants from CRI-Leisure. Only two participants did not complete the curiosity questionnaire. We also excluded participants who gave the same rating for more than 90% of the statements in the curiosity inventories or who did not answer the control question correctly (see below), suggesting that the questionnaires had not been truthfully answered (N = 2). Notably, in several cases, multiple of the exclusion criteria were met. The age of the participants who were included and excluded did not differ (p = .98).

The final sample consisted of 482 participants (190 younger adults, aged 18–30 years, 292 middle-to-older aged adults, aged 50–78 years). Of these, 440 participants were recruited via Prolific to take part in the online experiment and were compensated by 6 ₤/hour. The other 42 participants were recruited via the network of students of the Radboud University, who were involved in the study, and data were collected online using Gorilla Experiment Builder. These participants were not compensated for their participation. Of the final sample, 248 were female, 232 were male, two were non-binary. Four of the studies used no specific criteria regarding participants’ country of origin, however, participants were required to be fluent in English (Study 1, 5) or to be fluent in English or Dutch (Study 2, 4). One study (Study 3) included only participants from Europe, USA, Canada and Australia. This resulted in a somewhat imbalanced distribution of participants from different continents, countries, and races. Of the final sample, 64.9% were European (of which 47.9% were British and 19.68% were Dutch), 20.0% were North American (of which 96.9% were from the USA), 9.3% were African (of which 71.1% from South Africa), 2.5% were Asian, 1.9% were South American, and 1.4% were Australian.

Questionnaires

The online survey was designed and stored in Qualtrics for the studies hosted on Prolific and adapted to the Gorilla Experiment Builder platform for the other study. The participants could choose to complete the questionnaire in English or Dutch. For the Dutch versions, statements were translated from the original English versions of the curiosity scales and s-CRIq. In the studies run on Prolific, a control question was included in each questionnaire, such as: “Please select ‘Very slightly or not at all.’, to check whether participants indeed read the statements carefully.

Epistemic and perceptual curiosity scales

Curiosity was measured using 26 statements measuring epistemic curiosity (10 items13) and perceptual curiosity (16 items12). Of the epistemic curiosity scale, half of the items measured the I-Type epistemic curiosity and the other half measured D-Type epistemic curiosity. Example statements for the different curiosity dimensions are “I like to explore my surroundings” (perceptual curiosity), “When I learn something new, I like to find out more about it” (I-Type epistemic curiosity), and “I get frustrated if I can’t figure out a problem, so I work harder.” (D-Type epistemic curiosity). The statements were answered on a four-point Likert scale with the following answer options: “Almost never”, “Sometimes”, “Often”, and “Almost always”. The internal consistency of the epistemic and perceptual curiosity scales were reported to be between 0.75 and 0.87 in different studies12,13,15. The raw scores for each dimension were calculated as the sum of individual items. We further computed standardized scores of each curiosity dimension as the sum divided by the number of items (i.e. mean score across items per scale, ranging between 1 and 4), to make the scores of the dimensions comparable.

s-CRIq. To measure CR, we used a version of the short online Cognitive Reserve Index Questionnaire (s-CRIq49). A review of studies including both brain pathology and cognitive function measures support the hypothesis that CRIq scores can indeed account for the mismatch between cognitive performance and pathology50. We used the s-CRIq in English and Dutch. The English version was based on the s-CRIq of Mondini et al.35 and the Dutch version was based on a translation of the English version. For two out of the four included datasets, we adjusted the work question to allow limited responses and give more examples, to reduce the number of exclusions due to implausible answers (see exclusions).

The questionnaire is subdivided into three domains, which reflect the different sub-scores summing up to the total cognitive reserve index (CRI): CRI-Education, CRI-Work, and CRI-Leisure. The raw score of CRI-Education was calculated based on the sum of the years of education and additional courses, which lasted at least 6 months and involved a teacher or a final exam. We additionally asked participants about their highest educational degree. If the indicated degree did not match the reported years of education (suggesting the question had been misunderstood), we corrected the years of education by the mean duration for the indicated educational level based on the remaining participant’s data. The CRI-Education was corrected for 51 participants. Since education duration was corrected, the only reason for CRI-Education calculation exclusion was based on filling the course question too high (due to implausibly many years of courses, such as > 20 years).

The raw CRI-Work score was based on the years of paid work undertaken in adult life (since the age of 18). The participants were asked to fill in the job titles and duration in years, for a maximum of five jobs. They could also indicate that they had never worked. The jobs were scored on a scale from 1 to 5 based on the cognitive load, difficulty, and responsibility. The scoring was based on the international standard classification of occupations (ISCO), list ISCO08, for English jobs, and the BRC2014 (created by the Dutch Central Office for Statistics, Centraal Bureau voor Statistiek, CBS, which is based on the ISCO08 but adjusted to fit the Dutch job market) for Dutch jobs that did not match for the international job list. The scoring of jobs was done by two independent researchers who together decided on the final score. In cases of discrepancies or unclarities, a third researcher (ID) was consulted who was mainly responsible for the scoring of the s-CRIq across all studies. The raw score of the CRI-Work was based on the years spent on each job multiplied by the score assigned to that job. Only the three most relevant jobs, that is, the jobs with highest complexity and longer durations resulting in higher scores, were included to create the raw total job score. For example, if someone worked as a waiter for one year, secretary for five years, project manager for five years, and organizational officer for 10 years, only the last three jobs would be scored). For CRI-Work, participants were excluded if they did not provide scorable job information (i.e. did not indicate a job title), did indicate impossible job durations (such as 30 years of work experience within a single job at the age < 30), or did not fill in job durations and did not check the “never worked” box.

The CRI-Leisure raw score was calculated based on the frequency and duration of leisure activities carried out during the adult lifespan (since the age of 18) outside of school and work. This was assessed by five questions on activities, such as, “Have you ever taken trips or holidays lasting more than one day at least three times per year?”. The years spent on each activity were summed up. Furthermore, participants were asked if they had children and, if so, how many. Having one child resulted in 15 extra points, and an additional 5 points were given for each additional child. Participants were excluded from the CRI-Leisure calculation when they checked a box indicating that they had performed a specific activity for their entire adult life (18 years and older) and additionally filled in the field in which they could specify the years they had performed this activity. When the checkbox result (i.e., age – 18) did not align with the years they filled in, they were believed to have misunderstood the question and were excluded.

Following the computation of the raw scores per domain, scores were corrected for participants’ age. Age naturally affects the raw scores, as with increasing lifetime, participants had more time for education, jobs and promotions, and for performing various leisure activities. We performed three linear regressions (one for each domain), with the domain raw score as dependent variable and age as predictor. The obtained residuals from these regressions represented the adjusted score after removing the age effect, according to the s-CRIq guidelines46. The resulting residuals were standardized to a mean of 100 and a deviation of 15 for each CRI subscore (CRI-Education, CRI-Work, and CRI-Leisure). The overall CRI score was calculated as the average of the subscores, also standardized to a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. Note that as a result of the sample-based standardization, CRI scores cannot be interpreted as reflecting CRI scores relative to a larger population. Instead, they reflect the individual differences within the present sample. All computations were performed using R. For details on computations of the s-CRIq scores, see49.

Data analyses

First, we compared the raw curiosity scores and age-corrected and standardized s-CRIq scores of younger and middle-to-older aged participants to test for age group differences. All further analyses aimed at examining the relationships between curiosity and CR were run separately within the groups of younger and middle-to-older age participants and we used standardized curiosity scores and s-CRIq scores. We first examined the bivariate relationships between all variables using Pearson correlations. The power (1 – β error probability) for detecting a small-to-moderate effect (ρ = 0.20) with α = 0.05 (one-tailed) was 0.87 in the young group and 0.96 in the older group. Significances are based on corrections for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni-Holm correction (nine comparisons per group, resulting in step-wise adjusted α level of 0.0056–0.05). Age group differences in these correlations were tested using Fisher’s z.

Notably, the correlations among multiple predictors complicate a direct interpretation of the bivariate relationships of the variables. Thus, as a next step, we used multiple linear regression models to assess whether I-Type epistemic curiosity (EC-I), D-Type epistemic curiosity (EC-D), and perceptual curiosity (PC) independently, predicted the CRI subscores, CRI-Education, CRI-Work, and CRI-Leisure, in each age group separately. To control for any possible effects of age within each sample, we further included age as a continuous variable as an independent predictor in all models. The power (1 – β error probability) for detecting a small-to-moderate effect (f2 = 0.10) in a multiple regression with four predictors, with α = 0.05, was 0.95 in the young group, and 0.99 in the older group. Multicollinearity was assessed based on the variance inflation factor (VIF).

Results

Descriptive statistics and age group differences

The group comparisons (Table 1) showed no age group differences in any of the CRI subscores. All curiosity scores were significantly lower in the middle-to-older age group than in the young adult group.

Correlations

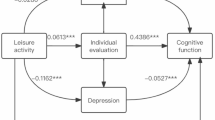

The bivariate correlations showed, overall, the expected positive relationships between CR and trait curiosity, both in younger and older adults (Fig. 1). The linear relationships are plotted in Fig. 2. In the younger sample, significant correlations were observed between CR-Leisure and I-Type epistemic curiosity and between CR-Leisure and perceptual curiosity. Positive relationships are also observed in the older sample, thus, the correlations between CR-Leisure and I-Type epistemic curiosity and perceptual curiosity did not differ between age groups (both z < 0.40, p > .35). In the older sample, I-Type epistemic curiosity and perceptual curiosity were not only related to CR-Leisure, but also to CR-Education. Accordingly, the relationship between I-Type epistemic curiosity and CR-Education was marginally significantly larger in the older than in the younger adults (z = -1.61, p = .05). Furthermore, D-type epistemic curiosity correlated with CR-Work more in the older sample than in the younger sample (z = -2.07, p = .02). Finally, measures of CR and curiosity correlated with age in the younger sample, but not in the older sample (all z > 2.21, all p < .02), except D-Type epistemic curiosity, which was not correlated with age in either group (z = 0.416, p = .34).

Regressions

Next, we ran multiple linear regression models for each age group and each subdomain of CR separately, to test whether the dimensions of curiosity would predict the CR subscores independently of each other. Age was included as an additional predictor. The VIF was < 2 for all analyses, indicating that the variances of the regression coefficients were not strongly affected by multicollinearity between the predictor variables. In all regression models, the residuals were normally distributed and homoscedastic.

The multiple linear regressions predicting CR-Education were significant for both younger adults (R2 = 0.09, F(185,4) = 4.71, p = .001), and older adults (R2 = 0.09, F(287,4) = 7.28, p = .001). In younger adults, only age predicted CR-Education significantly (β = 0.26, t = 3.67, p < .001), but none of the curiosity scores (all β < 0.09, t < 1.0, p > .35). By contrast, CR-Education was predicted by I-Type epistemic curiosity (β = 0.22, t = 3.00, p = .003) and perceptual curiosity (β = 0.15, t = 2.07, p = .04) in the older sample. Age and D-Type epistemic curiosity had no effect on CR-Education in older adults (both p > .22).

The multiple linear regression predicting CR-Work was significant for older adults (R2 = 0.07, F(287,4) = 5.24, p <. 001), but not younger adults (R2 = 0.03, F(185,4) = 2.16, p = .08). In younger adults, only age showed a trend effect on CR-Work, whereas none of the curiosity scores did (all β < 0.14, t < 1.20,p > .26). In the older sample, higher CR-Work was significantly predicted by higher D-Type epistemic curiosity (β = 0.22, t = 3.21, p = .001). I-Type epistemic curiosity had a positive effect (β = 0.14, t = 1.82) and perceptual curiosity had a negative effect (β = − 0.12, t = -1.67) on CR-Work in the older group, but both did not approach significance (both p > .06).

The multiple linear regressions predicting CR-Leisure were significant for both younger (R2 = 0.13, F(185,4) = 6.70, p < .001) and older adults (R2 = 0.13, F(287,4) = 11.14, p <. 001). In younger adults, higher CR-Leisure was significantly related to higher perceptual curiosity (β = 0.25, t = 2.77, p = .006) and related to younger age (β = − 0.21, t = -2.92, p = .004). Epistemic curiosity dimensions did not predict CR-Leisure in young adults (both p > .38). In the older group, higher CR-Leisure was predicted not only by higher perceptual curiosity (β = 0.29, t = 4.11, p < .001) and higher I-Type epistemic curiosity (β = 0.18, t = 2.50, p = .01), but also by lower D-Type curiosity (β = − 0.18, t = -2.74, p = .007). Age had no significant effect on CR-Leisure (p = .17) in the older group.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the relationship between multiple dimensions of trait curiosity and subdomains of CR, following the assumption that curiosity contributes to the build-up of CR by promoting engagement in stimulating activities over the lifespan. Our results generally support this assumption, providing evidence for a positive relationship between trait curiosity and CR. Furthermore, the relationship between trait curiosity and CR was found to be larger in the middle-to-older aged sample than in the young adult sample group, and was found to vary across different dimensions of curiosity and domains of CR. In younger age, only CR-Leisure was significantly predicted by perceptual curiosity. In the older age group, all CR-domains were related to curiosity, albeit to different dimensions of the trait: Higher interest-based (I-Type) epistemic curiosity and perceptual curiosity predicted higher CR-Education and CR-Leisure. In contrast, deprivation-sensitive (D-Type) epistemic curiosity was positively associated with CR-Work, but negatively associated with CR-Leisure.

In trying to further understand these associations, it is crucial to highlight the overlap and differences between the different types of curiosity. Perceptual curiosity and I-Type epistemic curiosity share a proactive, exploratory component of seeking new information, stimuli, environments, tasks, and experiences1,12,13,51. Individuals with high levels of perceptual and I-Type epistemic curiosity are thus intrinsically motivated to expand and open up to new fields of knowledge and engage in novel and stimulating activities. Perceptual and I-Type epistemic curiosity also covary17thus, many curious individuals may enjoy activities that combine perceptual exploration and epistemic learning experiences. In contrast, D-Type curiosity is more reactive, aiming to resolve knowledge gaps rather than seeking new ones14. Individuals with high levels of D-Type epistemic curiosity experience an urge to understand and solve problems and, thereby, eliminate uncertainty.

The age differences we observed in the relationships between dimensions of trait curiosity and CR domains may be due to subdomains of CR developing over different time scales across the lifespan. While CR-Education mostly builds up in young adulthood and remains relatively stable afterwards, CR-Work peaks in middle-age, whereas CR-Leisure continues to develop until later in life.

We found that CR-Education was predicted by perceptual and I-Type epistemic curiosity in middle-to-older age. Perceptual curiosity may specifically contribute to learning by exploring opportunities for sensory or experiential learning52. Interest-based curiosity may promote higher educational attainment more directly because it motivates individuals to engage deeply in educational activities and continue learning beyond formal education more long-term (for example, pursue advanced courses and degrees)53resulting in higher academic performance42. In turn, higher educational attainment achieved at a young age may also foster curiosity later in life54. The fact that we found the relationship between CR-education and trait curiosity to be larger in the older sample supports the assumption that the relationship is indeed bidirectional and mutually reinforcing and, thus, may increase over time.

CR-Work, reflecting the complexity of occupational attainment, was most strongly predicted by D-Type epistemic curiosity in middle-to-older age. D-Type epistemic curiosity may contribute to higher occupational achievements and attainment by fostering motivation and persistence to solve complex problems and adapt to challenges (similar to conscientiousness55,56). This trait may often lead to the development of expertise and skills, which improve job performance and open up opportunities for promotion57. The relationship between D-Type epistemic curiosity and CR-Work, again, was significant only in the older sample group. Presumably, any impact of trait curiosity on work-related choices and achievements will play out more from middle age onwards, when higher levels of job complexity and peak career level are typically achieved58,59.

Finally, we found a significant relationship between CR-Leisure and perceptual curiosity in both age groups and between CR-Leisure and I-Type curiosity in the middle-to-older age group. In contrast to educational and occupational achievements, which develop earlier and typically level off in middle age, leisure activities continue to develop over the lifespan and remain the most modifiable proxy of CR in later adulthood. Notwithstanding the lifespan-lasting increase in leisure activities as a source of CR, in younger as well as older age, leisure activities are mostly intrinsically motivated, which might be reflected in the relationship between trait curiosity and CR-Leisure we found across age groups. More specifically, individuals with high perceptual curiosity are likely to seek out novel, sensory experiences through traveling, exhibitions, creative or social activities. In addition, I-Type epistemic curiosity motivates leisure activities to deepen knowledge or immerse oneself in topics of personal interest, such as reading, attending intellectual and cultural events, and learning new skills (for example, a foreign language60).

The group differences in trait curiosity, albeit numerically small, were significant. However, age did not correlate with any dimension of trait curiosity within the older sample. Thus, any age differences in curiosity do not appear to be large, and the relationship between age and curiosity may not be linear. As such, curiosity does not seem to strongly decline with age. Importantly, however, our results indicate that the relationship between trait curiosity and CR is stronger in later adulthood. While CR levels did not overall differ between the age groups (as expected after correcting for age effects), the distribution of CR-Work and CR-Leisure (see Fig. 2) indicates relatively lower variability in the younger sample compared to the older sample. While formal education is usually completed in young adulthood, individual differences in occupational attainments and leisure activities evolve further over the adult lifespan and, thus, the influence of personality traits on CR-promoting behavior may be dynamic and increase over time. Specifically, compensatory cognitive and neural correlates of curiosity-driven behavior will only play out and affect CR later in life, once the brain is facing age-related neural changes or damage61. Finally, the relationship between trait curiosity and CR may be bidirectional and therefore increase later in life: individuals with high CR may also have more capacity to be curious or experience more stimulation and learning opportunities in novel or challenging situations, which in turn, further increases their CR30.

A number of studies have reported relationships between CR proxies and cognitive performance even in young adulthood62suggesting that there is an immediate association between cognition and CR. However, CR as an ability to cope with age-related changes in the brain, cannot be meaningfully assessed at a young age. Accordingly, at a young age, CR scores represent the current level of the measured CR proxies, rather than their later influence on an individual’s cognitive abilities in the face of brain damage. The young group of the present study had a mean age of 24.8, with a range of 18–30. This implies that many participants in this group did not yet complete their education, may not have entered the work force yet, or were at the beginning of their career. Accordingly, in the younger group, CR-Education and CR-Work were positively related to age, while the relationship to trait curiosity was very small. A simple explanation for this is that education is not yet completed and complexity of the jobs still increases within the age range of 18-3063. In addition, the formal school education and initial job training is largely driven by external factors, such as compulsory schooling laws and educational curricula64rather than self-motivated exploration and learning, driven by trait curiosity.

It is important to note a few limitations of this study that must be considered when interpreting the results. First, the reported associations are correlational in nature. Accordingly, we cannot infer any direct causal relationships between trait curiosity dimensions and CR domains. Second, we compare age groups in a cross-sectional approach. Therefore, we can only interpret differences between age groups, but no conclusions can be drawn about age-related changes over time in trait curiosity or its relationship to CR. Third, we did not have information on whether participants already entered the work force in the available data, which would be important to critically evaluate the CR-work scores particularly in the younger sample group. Furthermore, our study faces the common problems associated with online data collection, which is little control over the testing situation and the participants’ diligence and truthfulness of their answers. While we took measures to identify random answering and excluded participants based on implausible answers, we cannot be completely sure that all untruthful answers were removed. We did not set a time limit, or minimum duration needed, to answer a question in the questionnaires, which may have prevented participants from either answering questions too quickly or taking unnecessarily long time or breaks during questions.

Moreover, there might be an age-specific selection bias due to the online recruitment. Generally, much fewer older than younger eligible participants are registered on Prolific, and those who are might have a relatively higher educational level, affinity to technology, and, arguably, higher curiosity, than the general population in this age range65. Selection of the older participants who were recruited within the researcher’s networks was potentially also biased towards a more highly educated sample. Finally, most participants in our sample were from Europe and North America. Thus, the results may not generalize to populations from other countries, in particular considering cross-country differences in access to education and educational systems, time of transition to economic independence, as well as age of, and the privilege of, retirement.

To conclude, our results align with the emerging literature demonstrating that personality traits are related to CR37,40 and, thereby, potentially contribute to healthy cognitive aging19,20,21,66. In particular, we provide empirical evidence for the assumption that trait curiosity, presumably by influencing actions and decisions that we choose over our lifetime, impacts multiple CR-promoting factors28. The fact that the associations between curiosity measures and CR domains are more prominent in the older age supports the idea that curiosity is related to CR build up over a lifetime, rather than educational, occupational, or leisure activity status already at a young age. Understanding the relationship between dimensions of trait curiosity and domains of CR may help us to predict in which activities an individual will engage in and how this reflects on their cognitive functioning later in life. This knowledge is useful to plan early interventions to foster CR in individuals who, because of low levels of curiosity, are less intrinsically motivated to engage in reserve-promoting activities. Future studies may now further examine the longitudinal relationship between trait and state curiosity, CR, and cognitive performance measures across the lifespan with the goal to better understand the, potentially mutually reinforcing, relationship between CR and curiosity and its impact on cognitive performance and age-related decline.

Data availability

This study is part of the project “Curiosity and Cognition in Aging” (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5RYK9) shared in the Open Science Framework (OSF). The data are available here: https://osf.io/c8fsj/.

References

Litman, J. Curiosity and the pleasures of learning: wanting and liking new information. Cognition Emot. 19, 793–814 (2005).

Berlyne, D. E. A theory of human curiosity. Br. J. Psychol. 45, 180 (1954).

Berlyne, D. E. Conflict, arousal, and curiosity. (1960).

Loewenstein, G. The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation. Psychol. Bull. 116, 75 (1994).

Kidd, C. & Hayden, B. Y. The psychology and neuroscience of curiosity. Neuron 88, 449–460 (2015).

Litman, J. Curiosity: Nature, dimensionality, and determinants. (2019).

Spielberger, C. D. & Starr, L. M. Motivation: Theory and Research 221–243 (Routledge, 2012).

Kashdan, T. B. et al. The curiosity and exploration inventory-II: development, factor structure, and psychometrics. J. Res. Pers. 43, 987–998 (2009).

Kashdan, T. B., Rose, P. & Fincham, F. D. Curiosity and exploration: facilitating positive subjective experiences and personal growth opportunities. J. Pers. Assess. 82, 291–305 (2004).

Collins, R. P. Measurement of Curiosity as a Multidimensional Personality Trait (University of South Florida, 2000).

Reio, T. G. Jr, Petrosko, J. M., Wiswell, A. K. & Thongsukmag, J. The measurement and conceptualization of curiosity. J. Genet. Psychol. 167, 117–135 (2006).

Collins, R. P., Litman, J. A. & Spielberger, C. D. The measurement of perceptual curiosity. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 36, 1127–1141 (2004).

Litman, J. A. Interest and deprivation factors of epistemic curiosity. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 44, 1585–1595 (2008).

Litman, J. A. & Jimerson, T. L. The measurement of curiosity as a feeling of deprivation. J. Pers. Assess. 82, 147–157 (2004).

Litman, J. A. & Silvia, P. J. The latent structure of trait curiosity: evidence for interest and deprivation curiosity dimensions. J. Pers. Assess. 86, 318–328 (2006).

Costa, P. & McCrae, R. A five-factor theory of personality. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research 2, (1999).

Silvia, P. J. & Christensen, A. P. Looking up at the curious personality: individual differences in curiosity and openness to experience. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 35, 1–6 (2020).

Litman, J. A. & Mussel, P. Validity of the interest-and deprivation-type epistemic curiosity model in Germany. J. Individ. Differ. (2013).

Luchetti, M., Terracciano, A., Stephan, Y. & Sutin, A. R. Personality and cognitive decline in older adults: data from a longitudinal sample and meta-analysis. Journals Gerontol. Ser. B: Psychol. Sci. Social Sci. 71, 591–601 (2016).

Chapman, B. et al. Personality predicts cognitive function over 7 years in older persons. Am. J. Geriatric Psychiatry. 20, 612–621 (2012).

Curtis, R. G., Windsor, T. D. & Soubelet, A. The relationship between Big-5 personality traits and cognitive ability in older adults–a review. Aging Neuropsychol. Cognition. 22, 42–71 (2015).

Karsazi, H. et al. The moderating effect of neuroticism and openness in the relationship between age and memory: implications for cognitive reserve. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 176, 110773 (2021).

Payne, B. R. & Lohani, M. Personality and cognitive health in aging. Personality Healthy Aging Adulthood: New. Dir. Techniques, 173–190 (2020).

Roberts, B. W., Walton, K. E. & Viechtbauer, W. Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 132, 1 (2006).

Robinson, O. C., Demetre, J. D. & Litman, J. A. Adult life stage and crisis as predictors of curiosity and authenticity: testing inferences from erikson’s lifespan theory. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 41, 426–431 (2017).

Costa, P. T. Jr, Herbst, J. H., McCrae, R. R. & Siegler, I. C. Personality at midlife: stability, intrinsic maturation, and response to life events. Assessment 7, 365–378 (2000).

Giambra, L. M., Camp, C. J. & Grodsky, A. Curiosity and stimulation seeking across the adult life span: Cross-sectional and 6-to 8-year longitudinal findings. Psychol. Aging. 7, 150 (1992).

Sakaki, M., Yagi, A. & Murayama, K. Curiosity in old age: A possible key to achieving adaptive aging. Neurosci. Biobehavioral Reviews. 88, 106–116 (2018).

Ziegler, M., Cengia, A., Mussel, P. & Gerstorf, D. Openness as a buffer against cognitive decline: the Openness-Fluid-Crystallized-Intelligence (OFCI) model applied to late adulthood. Psychol. Aging. 30, 573 (2015).

Robertson, I. H. A right hemisphere role in cognitive reserve. Neurobiol. Aging. 35, 1375–1385 (2014).

Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia 47, 2015–2028 (2009).

Stern, Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 8, 448–460 (2002).

Nogueira, J., Gerardo, B., Santana, I., Simoes, M. R. & Freitas, S. The assessment of cognitive reserve: a systematic review of the most used quantitative measurement methods of cognitive reserve for aging. Front. Psychol. 13, 847186 (2022).

Colombo, B., Antonietti, A. & Daneau, B. The relationships between cognitive reserve and creativity. A study on American aging population. Front. Psychol. 9, 764 (2018).

Nucci, M., Mapelli, D. & Mondini, S. Cognitive reserve index questionnaire (CRIq): a new instrument for measuring cognitive reserve. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 24, 218–226 (2012).

Montoliu, T., Zapater-Fajarí, M., Hidalgo, V. & Salvador, A. Openness to experience and cognitive functioning and decline in older adults: the mediating role of cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia 188, 108655 (2023).

Coors, A., Lee, S., Habeck, C. & Stern, Y. Personality traits and cognitive reserve—High openness benefits cognition in the presence of age-related brain changes. Neurobiol. Aging. 137, 38–46 (2024).

Ihle, A. et al. Cognitive reserve mediates the relation between openness to experience and smaller decline in executive functioning. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 48, 39–44 (2019).

Sharp, E. S., Reynolds, C. A., Pedersen, N. L. & Gatz, M. Cognitive engagement and cognitive aging: is openness protective? Psychol. Aging. 25, 60 (2010).

Colombo, B., Piromalli, G., Pins, B., Taylor, C. & Fabio, R. A. The relationship between cognitive reserve and personality traits: a pilot study on a healthy aging Italian sample. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 32, 2031–2040 (2020).

Silvia, P. J. Curiosity and Motivation. (2012).

Von Stumm, S., Hell, B. & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. The hungry mind: intellectual curiosity is the third pillar of academic performance. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 6, 574–588 (2011).

Tang, X. & Salmela-Aro, K. The prospective role of epistemic curiosity in National standardized test performance. Learn. Individual Differences. 88, 102008 (2021).

Kashdan, T. B. & Steger, M. F. Curiosity and pathways to well-being and meaning in life: traits, states, and everyday behaviors. Motivation Emot. 31, 159–173 (2007).

Reio, T. G. Jr & Sanders–Reio, J. Curiosity and well–being in emerging adulthood. New. Horizons Adult Educ. Hum. Resource Dev. 32, 17–27 (2020).

Torenvliet, C., Jansen, M. G. & Oosterman, J. M. Age-invariant approaches to cognitive reserve. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 1–19 (2025).

Wei, W., Wang, K., Shi, J. & Li, Z. Instruments to assess cognitive reserve among older adults: a systematic review of measurement properties. Neuropsychol. Rev. 34, 511–529 (2024).

Pinto, J. O., Peixoto, B., Dores, A. R. & Barbosa, F. Measures of cognitive reserve: an umbrella review. Clin. Neuropsychol. 38, 42–115 (2024).

Mondini, S. et al. s-CRIq: the online short version of the cognitive reserve index questionnaire. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 35, 2903–2910 (2023).

Kartschmit, N., Mikolajczyk, R., Schubert, T. & Lacruz, M. E. Measuring cognitive reserve (CR)–A systematic review of measurement properties of CR questionnaires for the adult population. PloS One. 14, e0219851 (2019).

Berlyne, D. E. Novelty and curiosity as determinants of exploratory behaviour. Br. J. Psychol. 41, 68 (1950).

Dosher, B. & Lu, Z. L. Perceptual Learning: How Experience Shapes Visual Perception (MIT Press, 2020).

Litman, J. A., Crowson, H. M. & Kolinski, K. Validity of the interest-and deprivation-type epistemic curiosity distinction in non-students. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 49, 531–536 (2010).

Gottfried, A. E. et al. Latent profiles of high school academic intrinsic motivation: relations to educational attainment, curiosity, and work and leadership motivation in adulthood. Motivation Sci. 9, 242 (2023).

Frieder, R. E., Wang, G. & Oh, I. S. Linking job-relevant personality traits, transformational leadership, and job performance via perceived meaningfulness at work: A moderated mediation model. J. Appl. Psychol. 103, 324 (2018).

Van Aarde, N., Meiring, D. & Wiernik, B. M. The validity of the big five personality traits for job performance: Meta-analyses of South African studies. Int. J. Selection Assess. 25, 223–239 (2017).

Richards, J. B., Litman, J. & Roberts, D. H. Performance characteristics of measurement instruments of epistemic curiosity in third-year medical students. Med. Sci. Educ. 23, 355–363 (2013).

Nagy, N., Froidevaux, A. & Hirschi, A. in Work Across the Lifespan 235–259 (Elsevier, 2019).

Härkönen, J. & Bihagen, E. Occupational attainment and career progression in Sweden. Eur. Soc. 13, 451–479 (2011).

Mahmoodzadeh, M. & Khajavy, G. H. Towards conceptualizing Language learning curiosity in SLA: an empirical study. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 48, 333–351 (2019).

Stern, Y. et al. Brain networks associated with cognitive reserve in healthy young and old adults. Cereb. Cortex. 15, 394–402 (2005).

Panico, F., Sagliano, L., Magliacano, A., Santangelo, G. & Trojano, L. The relationship between cognitive reserve and cognition in healthy adults: a systematic review. Curr. Psychol. 42, 24751–24763 (2023).

OECD. Typical graduation ages, by level of education (2020). (2022).

OECD. Education at a Glance 2022. (2022).

Greene, N. R. & Naveh-Benjamin, M. Online experimentation and sampling in cognitive aging research. Psychol. Aging. 37, 72 (2022).

Hill, N. L., Kolanowski, A. M., Fick, D., Chinchilli, V. M. & Jablonski, R. A. Personality as a moderator of cognitive stimulation in older adults at high risk for cognitive decline. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 7, 159–170 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lena Teunissen, Sandrina Ilyia, Kate Broekhans, and Lynn Sahhar for the support with the data collection.

Funding

This research was funded by an Open Competition grant awarded to IW by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) for the project “Curiosity in cognitive aging” (406.XS.03.021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Iris Wiegand: Conceptualization, Project Administration, Formal Analyses, Supervision, Writing – Original Draft, Review, and Editing, Funding, Resources. Isabel Donkers: Investigation, Project Administration, Data Curation, Formal Analyses, Methodology, Software. Sebastian Balart-Sanchez: Investigation, Writing –Review, and Editing. Marianna Pope: Investigation, Writing –Review, and Editing. Gaspar Pérez-Ayora: Investigation, Writing –Review, and Editing. Joukje M. Oosterman: Conceptualization, Writing –Review, and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiegand, I., Donkers, I., Balart-Sanchez, S. et al. The relationship between trait curiosity and cognitive reserve in younger and older adults. Sci Rep 15, 24707 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10101-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10101-2