Abstract

Social anxiety symptoms are highly prevalent in adolescents and negatively impact their social and academic functioning, highlighting the need for effective low-threshold interventions. This randomised controlled trial evaluated the guided online intervention SOPHIE for adolescents (N = 133; 11–17 years) with social anxiety disorder (SAD; treatment) or subclinical social anxiety (indicated prevention) compared to care-as-usual control condition and qualitatively explored their experiences. Outcomes were assessed at baseline, mid-intervention (4 weeks), post-intervention (8 weeks) and 5-month follow-up and analysed using linear mixed-effects models. SOPHIE did not significantly reduce social anxiety symptoms post-intervention but showed a significant between-group effect at follow-up (d = 0.67, 95%CI [0.32;1.02]). Subgroup analyses by diagnostic condition showed a significant between-group effect at follow-up in the subclinical social anxiety (d = 1.53, 95%CI [1.74;0.41]) but not in the SAD condition. Social functioning significantly improved at post-intervention and follow-up, with medium to large effects (post: d=-0.73, 95%CI [-1.08; -0.37]; follow-up: d=-0.32, 95%CI [-0.66; 0.02]). Qualitative interviews post-intervention revealed that participants found the intervention beneficial, although some found exposure exercises challenging and desired additional support. Very heterogeneous needs emerged regarding the guidance provided during the programme. Low-threshold online interventions for adolescents with social anxiety may be effective, particularly as an indicated prevention approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adolescence represents an important period in the development of social anxiety disorder (SAD), with a mean age of onset of 14 years1. In population-based adolescent samples, the point prevalence of clinician-assessed SAD-criteria is 2.6%, while up to 50% report subclinical levels of social anxiety symptoms2,3,4,5,6,7. If left untreated, SAD has a high likelihood of persisting into adulthood and may lead to the development of other disorders as well as lower social and academic functioning8,9,10,11,12. Highly scalable, low-threshold intervention programs, such as online interventions, could be a promising strategy to prevent such negative long-term consequences and to address the care gap that is especially pronounced in adolescents13.

Online interventions have shown small but significant effects in reducing anxiety symptoms in adolescents with an anxiety disorder14,15,16 but research on online delivered prevention is still inconclusive. In face-to-face settings, meta-analytic evidence has shown that indicated transdiagnostic interventions yield small but significant effects in reducing anxiety symptoms among adolescents at risk for several anxiety disorders17. In online settings however, even though some studies found a small significant reduction in subclinical anxiety symptoms, meta-analytic results on universal and targeted prevention programmes could not confirm this18,19. Low participation and high dropout rates and challenges regarding the implementation and sustaining use of online interventions in adolescent studies may contribute to these low effects. Human support in the form of guidance may help to address these issues20,21 as guided interventions based on Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) have often demonstrated to be more effective in adolescent samples than unguided self-help or other psychological interventions22.

Next to human guidance, tailoring interventions specifically to SAD may yield better outcomes as adolescents with SAD symptoms benefited more from SAD-specific content than from interventions focusing on anxiety in general23,24,25,26,27,28. Such interventions specifically designed for SAD could target mechanisms involved in developing and maintaining SAD. Etiological models of social anxiety29,30,31,32 propose overlapping factors that contribute to maintaining SAD and form the basis of SAD-specific interventions. These include cognitive processes such as negative social-evaluative cognitions and self-focus during social situations, as well as behavioural processes such as avoidance behaviours beforehand and safety behaviours during social interactions33. Randomised controlled trials (RCT) investigating online interventions based on such models, specifically the Cognitive Model of Social Phobia by Clark and Wells and the Cognitive-Behavioural Model of Anxiety in Social Phobia by Rapee and Heimberg, in clinical adolescent samples with SAD showed significant reductions in social anxiety and improvements in social functioning34,35,36. None of these RCTs has specifically targeted subclinical levels of social anxiety.

Previous research on the evaluation of online interventions is mainly based on RCTs. Integrating qualitative elements in RCTs could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the intervention’s impact and the contextual factors influencing its efficacy. Further, it offers the possibility to involve adolescents’ voices thereby democratising inputs to research37,38. A previous RCT included a qualitative evaluation of adolescents’ experiences with an online intervention for SAD: Adolescents appreciated the autonomy when working through the modules at their own pace and the flexibility in contact with the person providing guidance39. They considered the exposure exercises to be the most challenging but also the most helpful ones. These qualitative results were reported separately from the quantitative efficacy results36,39 although a combined discussion could provide a more integrated understanding of the effects40.

Overall, initial studies suggest positive effects of online interventions on adolescents with SAD, but evidence on those with subclinical symptoms is limited. There is little qualitative research on adolescents’ experiences of using such interventions. Thus, the primary aim of this RCT was to evaluate the efficacy of an online intervention called SOPHIE41 developed to reduce subclinical social anxiety (i.e., indicated prevention) and SAD (i.e., intervention) by targeting the psychological mechanisms postulated by the Clark & Wells’ Cognitive Model30 (i.e., self-focused attention, negative automatic thoughts during a social event, and pre- and post-event processing of this situation, as well as safety behaviour and avoidance) by comparing the effects of the intervention group with those of the care-as-usual (CAU) control group on social anxiety symptoms at post- (primary outcome; 2 months after randomisation) and follow-up (5 months after randomisation) assessments. Secondary outcomes included remission of SAD diagnosis, generalised anxiety, depression, self-esteem, quality of life, level of functioning, and social anxiety assessed by guardians. Further, the participants’ experiences of using the SOPHIE program were explored through qualitative interviews.

Results

Participants

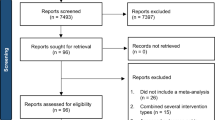

Recruitment of adolescents aged 11 to 17 years started in August 2021 and ended in August 2023 due to regulatory reasons. Last assessment was in March 2024. Recruitment of participants with subclinical social anxiety resulted in a lower sample size than targeted even though a comprehensive recruitment plan was followed. The SAD-group sample size was increased from the planed sample size of N = 56 to N = 80 participants, to account for dropouts and incomplete assessments42. In total, 164 participants provided informed consent or assent. Of these, 133 completed baseline assessments and were randomised to the SOPHIE intervention or CAU group. Additionally, 117 guardians completed assessments at least once. The CONSORT flow diagram (see Fig. 1) illustrates the progression of participants while baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences between study groups in terms of demographic, clinical, or outcome variables.

During the intervention period, n = 18 (intervention group: n = 9; CAU group n = 9) adolescents received weekly or biweekly psychotherapy, n = 5 (intervention group: n = 5; CAU group n = 0) adolescents were supported by psychosocial professionals (e.g., social workers), and n = 5 (intervention group: n = 3; CAU group n = 2) adolescents were medicated with psychotropic drugs. For the intervention group, Table 2 provides details on adherence rates, amount of guidance, any reported negative effects due to the intervention and participants’ overall satisfaction with the intervention.

Missingness and dropout analysis

The percentage of missing values on the primary outcome (SPIN) was 27% and on secondary outcomes 28% in total. Telephone interviews had higher missingness (44% at post-assessment and 53% at follow-up). Demographic variables and baseline assessments did not predict missingness at mid-, post-, or follow-up assessments supporting missingness at random (MAR). Only younger age at baseline was significantly associated with missingness at follow-up (β = 0.27, p < 0.05). Adolescents in the CAU control group tended to complete more assessments, but the difference was only significant at post-assessment (X2(1) = 6.04, p < 0.05).

Efficacy analysis

Mean SPIN scores over time are shown separately for both study groups (SOPHIE vs. CAU) and diagnostic conditions (SAD vs. subclinical) in Fig. 2. Observed and estimated means of primary and secondary outcomes of the linear mixed-effects models from baseline to post-intervention are reported in Table 3. Table 4 displays intercept and estimates of the linear mixed-effects models on primary and secondary outcomes for time and group interaction from baseline to post and corresponding between and within group effect sizes. Observed and estimated means at follow-up are reported in Table 5, and coefficients derived of the linear mixed-effects models and effect sizes are displayed in Table 6.

The primary outcome (SPIN score at post-assessment) did not differ significantly between the two study groups. However, the SOPHIE group had significantly lower SPIN scores compared to the CAU group at follow-up (p < 0.001; Table 6) with a medium to large between-group effect size. Subgroup analyses were run for both diagnostic condition SAD and subclinical social anxiety. For the SAD condition, there was no significant difference between the intervention group and the control group at post- and follow-up assessment. For the subclinical condition, no significant difference was found at post-assessment, however, the intervention group revealed significantly lower levels of social anxiety compared to the control group at follow-up (p < 0.001; Table 6) with a large between-group effect size.

The secondary outcomes at post-assessment including social functioning, depression, general anxiety, social fears and avoidance, and quality of life improved significantly in the intervention group compared to CAU (p < 0.004; Table 4) with small to medium between-group effect sizes but not role functioning, self-esteem and guardian rated social anxiety (p ≥ 0.134; Table 4). At follow-up, significant improvements could be maintained in social functioning (p < 0.001; Table 6) with a small between-group effect, while role functioning, depression, general anxiety, social fears and avoidance, quality of life, self-esteem and guardian rated social anxiety did not change significantly (p ≥ 0.098; Table 6).

Remission of SAD in the clinical group yielded no significant differences between the intervention and control condition at post- and follow-up assessment (p ≥ 0.118). In the clinical intervention group, 63% of the adolescents met diagnostic criteria for SAD at post-assessment and 80% at follow-up; in the clinical CAU group, 74% at post-assessment and 65% at follow-up.

The sensitivity analyses using the per-protocol sample (i.e., participants who completed baseline, mid-intervention, and post-intervention assessments for the post-assessment model, and all four assessments for the follow-up model) generally supported the ITT results. At follow-up, the SPIN scores differed significantly between the SOPHIE and CAU conditions (p < 0.001). In contrast to the ITT analyses, a significant difference between study conditions was also observed at post-assessment (p = 0.032). Subgroup analyses by diagnostic condition yielded the same results pattern as in the ITT-analysis (see Supplementary Table 2).

Qualitative analysis

Out of N = 32 eligible adolescents, n = 17 participated in the qualitative interview. For this sample, information on demographic and intervention usage is provided in supplementary Table 1. Four main summary domains were identified, detailing adolescents’ experiences with the intervention: (I) therapeutic relationship, (II) factors contributing to or preventing engagement with the intervention, (III) adolescents’ reflection on their symptom and behaviour changes, and (IV) adolescents’ evaluation of the SOPHIE intervention content. Definitions, subdomains and examples are described in Table 7. The relationship with the e-coach varied greatly (i.e., domain I). Some adolescents found it supportive, others perceived it as impersonal like a chatbot, or even as stressful and uncomfortable because they assumed that their progress in the intervention was observed. E-coaches were also seen as providing a clear structure that helped some adolescents to make progress. Additionally, some adolescents appreciated the format of remote support, without the need to visit a therapist.

Adolescents discussed further factors contributing to their engagement with the intervention (i.e., domain II). Awareness of the problem and motivation to change played key roles, especially in the early phase of the intervention. Interest in the content and personal improvements acted as motivators to continue. Structure of the program, including reminders by e-coaches or parents, or module structure, were perceived as helpful to plan and organise the use of the intervention over the eight weeks. The most common barrier to engagement was lack of time or forgetting.

When adolescents reflected on changes in their symptoms and behaviour (i.e., domain III), their responses diverged: some reported symptomatic improvement, others noted partial improvement but felt that more time was needed, and some reported no improvement or worsening of their problems. Some noticed tangible improvements in daily life, while others struggled, especially with behavioural tasks such as exposure exercises. Although they could understand the importance of doing exposure exercises, many found it challenging to implement them independently and some indicated that they would need additional support.

The content of the intervention (i.e., domain IV) was generally understandable and relevant. Some felt seen and understood because of examples and videos that were targeted to them (i.e., problems, age group). Younger adolescents sometimes struggled to understand the psychoeducational content but could seek help from their parents. Exercises were generally regarded as helpful and suitable although some found it difficult to adapt them to their own lives and thus did not engage in them.

Discussion

The primary aim of the RCT was to evaluate the efficacy of the online intervention SOPHIE in reducing social anxiety in adolescents. While no significant difference between the intervention and control group was found post-intervention in social anxiety, a significant difference emerged at 3-month follow-up with a medium to large effect size. Subgroup analysis showed significant differences with a large effect size for the subclinical group (i.e., indicated prevention) at follow-up but not for the SAD group (i.e., treatment). Secondary outcomes, such as depression, general anxiety, social fear and avoidance, and quality of life, showed significant improvement post-intervention with small to large effect sizes. However, these improvements were not sustained to follow-up. The intervention group significantly improved in level of social (but not role) functioning at post- and follow-up assessments with small to medium effect sizes. Guardians reported no significant changes in their child’s social anxiety.

Adolescents in the intervention group were interviewed to gain information on their experiences using the SOPHIE programme. In the qualitative analysis four main topics were explored (1) therapeutic relationship, (2) factors that contributed to and prevented engagement with the intervention, (3) reflections on symptom and behaviour change, and (4) adolescents’ evaluation of the SOPHIE intervention content.

The non-significant intervention effect on social anxiety after the intervention is inconsistent with previous online intervention studies in adolescents with SAD34,35,36. However, social anxiety was significantly reduced at follow-up suggesting a delayed response. One possible explanation is that adolescents may require more time than an eight-week intervention period to practice the learned strategies and to implement the acquired knowledge and skills to everyday life25,43. This aligns with previous evidence that cognitive and behavioural gains from anxiety treatments in adolescents continue to develop after the intervention period and can show a delayed response26,44. A further explanation for the delayed response could be drawn from the Cognitive Model of Social Phobia30 which posits that social anxiety is maintained by mechanisms such as avoidance behaviour29. In this study, avoidance behaviour significantly decreased at post-intervention but not at follow-up suggesting early reductions may have led to later symptom reduction. This temporal pattern, in which changes in maintaining mechanisms precede social anxiety symptom changes, has been observed in another study,45. Thus, targeting the proposed mechanism in interventions might be needed to facilitate subsequent improvements in social anxiety.

Notably, the significant difference in social anxiety at follow-up was mainly driven by the reductions in the subclinical but not in the clinical group. This is in line with previous research on indicated prevention of social anxiety symptoms in face-to-face settings, specifically in group formats46. In contrast, indicated prevention delivered online showed significant small effects for depressive but not for anxiety symptoms in meta-analyses19,47. This inconsistent evidence may partly be due to varying recruitment strategies in identifying adolescents at risk for the development of a mental disorder and that social anxiety symptoms specifically are poorly recognised by affected adolescents and their social context2,48,49 resulting in heterogenous samples with different needs, problem awareness and treatment motivation50.

The clinical SAD-group showed only little improvement in this study. This may be due to high rates of comorbidities and impaired functioning that characterized our clinical sample. Consequently, some participants may have been too burdened to benefit from a guided self-help approach with a focus on social anxiety. This may also explain the rather low SAD-remission rates found in our study and a similar online intervention for adolescents34. These participants may require more intensive treatments addressing multiple problems. Additionally, some adolescents participated simultaneously in psychotherapy in a face-to-face setting, suggesting a need for a coordination of these interventions using blended formats51.

Adolescents were primarily enrolled through their guardians, highlighting their essential role in adolescents’ help-seeking behaviour52. However, guardians reported no significant changes in social anxiety at all assessment points, unlike adolescents. This may be explained by discrepancies generally found between adolescent and guardian reports, particularly pronounced in internalised disorders53,54,55.

The SOPHIE-intervention led to positive effects on social functioning. This effect is in line with previous RCTs of online interventions for SAD in adolescents that also reported significant improvements in global functioning post-intervention29,34,35. In this study, social but not role functioning increased significantly at both post-intervention and follow-up, suggesting a generalisation effect on adolescents’ social environment. This highlights that the intervention may have differential effects on everyday life and may be especially relevant for the social behaviour of adolescents. Unchanged role functioning may indicate that improvements in academic and vocational functioning takes more time to manifest, emphasizing the importance of early interventions to prevent negative long-term impacts56.

Although significant differences in depression, general anxiety and quality of life were found at post-assessment, these effects have attenuated until follow-up. Additional interventions targeting specific disorders or a transdiagnostic approach may be warranted to improve these effects over the long term, particularly in the presence of comorbidities57. These results are in line with other studies on online interventions for adolescents that demonstrated no significant effects of anxiety-focused interventions on depression and quality of life58.

Adolescents experienced the SOPHIE-intervention as beneficial and supportive but challenging like previous qualitative results in context of online interventions for adolescents with SAD39. Exposure exercises were perceived as the most difficult ones. Thus, guidance could be specifically intensified during the planning and implementation of these exercises. This would support adolescents at the right time without generally restricting their autonomy. This seems especially relevant because some adolescents felt controlled and pressured by the regular weekly guidance, suggesting the need for varied guidance formats. The effect of letting adolescents choose their preferred guidance format at the start of the intervention could be investigated in future studies e.g.,59.

Most adolescents noticed initial improvements in symptoms during the intervention but needed more time for implementing it to their everyday lives, which is consistent with efficacy results on social anxiety that were only significant at follow-up. If content was not directly relevant to their situation, they reported implementing it less often or not at all. Additional guidance on demand could be helpful to support to better tailor the exercises and modules to the very specific needs of the participants i.e.,39. This may improve the implementation of online interventions and their efficacy. To this aim, future research could make use of techniques such as the think-aloud method to explore adolescents’ real-time use of the intervention to gain more detailed user-led information on their specific needs60,61.

These results should be interpreted considering some limitations. The sample was a self-selected group of adolescents who had expressed an interest in the SOPHIE intervention which may limit the generalisability of the results. In addition, the targeted sample size for the subclinical group was not reached. Nonetheless, post hoc power analyses indicated that the study still had sufficient power to detect effects in the overall, clinical and subclinical group at follow-up. Despite this, the limited sample size may have constrained the ability to detect smaller effects that could emerge in a larger sample with more participants exhibiting subclinical symptoms. Importantly, the use of a clinical interview to exclude participants with a past and present diagnosis of a SAD to define the subclinical group represents a methodological strength, and future research should aim to better recognise adolescents with subclinical levels of social anxiety and investigate larger-scale SAD-specific prevention programs. As the intervention effects only became evident at the time of the 5-month follow-up, no conclusions can be made about longer-term improvements and the full impact of the intervention; to evaluate this a longer follow-up period in future studies is needed. Adolescents in the qualitative study were mostly committed to the intervention, thus limiting the in-depth exploration of barriers to intervention engagement. Future studies could capitalise on the strengths of mixed-method approach and look even more in-depth at the experiences of adolescents, especially those who make less use of the intervention. Moreover, the investigation of various means of support for adolescents before and during the usage of the intervention (e.g., by including modules tailored to their needs, personalised formats of guidance)36 may further increase the efficacy of intervention. Additionally, introducing exposure exercises early during the intervention could be beneficial, particularly considering decreasing adherence over time46.

Conclusion

This study adds to previous evidence on the efficacy of disorder-specific online interventions for social anxiety based on conceptual models such as the cognitive model30 and supports the longer-term efficacy of online interventions for social anxiety, particularly for subclinical social anxiety. It further suggests new avenues to personalise future interventions. Leveraging online interventions has the potential to substantially improve mental health in adolescence and beyond.

Method

Study design

This RCT investigated the effects of the online intervention SOPHIE compared to a care-as-usual (CAU) control group in adolescents with subclinical social anxiety or SAD. The trial had a 2 × 2 × 4 design: experimental condition (SOPHIE vs. CAU), diagnostic condition (SAD vs. subclinical social anxiety), and repeated assessments (baseline, mid-intervention at four weeks, post-intervention at eight weeks, and follow-up at five months after randomisation). Qualitative interviews were conducted post-intervention with participants in the intervention condition.

The trial was registered in clinicaltrials.gov (date of first registration: 04/03/2021; registration number: NCT04782102) and was conducted following the declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Canton Bern in March 2020 and the amendment to implement the qualitative study in May 2022 (CEC Bern, Project ID 2020–02501). Detailed information (except for the qualitative interview) is provided in the study protocol41. The trial further included assessment on potential mediators and moderators of the effects of the intervention which will be published separately.

Participants

Sampling strategy

A self-selected sample of participants was recruited in the German speaking countries (Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Liechtenstein) from August 2021 to August 2023. To reduce self-selection bias and support the sampling of adolescents with subclinical social anxiety, a recruitment strategy was established to distribute information about social anxiety, SAD and the possibilities of digitally offered help among three target groups: adolescents, their caregivers and their professional network. All information and promotional materials were adapted to the target groups’ needs and brought to them by different means of communication. Adolescents were targeted by advertisements on social media channels (i.e., Instagram and TikTok), school visits, workshops, flyers and posters in buildings frequented regularly by adolescents (e.g., youth centres). Caregivers were targeted by information postings in educational magazines, newsletters from parents’ associations, internet forums and advertisements on Google. The professional network adolescents are embedded in (i.e., teachers, social workers, school mental health specialists, therapists and primary physicians) was informed by collaborations with partner organisations, workshops and information talks given by the first and last authors.

Participants for the qualitative interviews were recruited from the intervention group of the RCT beginning in July 2022, following receiving ethical approval for the qualitative component of the study. After this time point, 36 adolescents were randomised to the intervention group. Of these, 4 withdrew consent prior to the post-intervention assessment, leaving 32 eligible participants. All 32 were invited to participate in the qualitative interviews, and 17 participated. See the supplementary material for an analysis of differences between adolescents who participated in the interview and those who did not.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria required participants to be 11 to 17 years old, understand German, have access to a device connected to the Internet, and score 16 or higher on the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN). This threshold was chosen following previous research62. Exclusion criteria were a known diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, acute suicidality at baseline, and a past diagnosis of SAD for the subclinical group. All participants who consented and were randomised to the intervention group were eligible for the qualitative interview.

Procedure

Informed consent (14 to 17 years) and informed assent with guardian consent (11 to 13 years) were obtained. Baseline assessment included questionnaires and a diagnostic telephone interview. Participants were then randomly allocated to the intervention or CAU group via stratified block randomisation based on diagnostic status (SAD vs. subclinical social anxiety). Randomisation parameters (number of groups, allocation ratio (1:1), and block size) were set up by the first author using Qualtrics embedded in the last baseline assessment. The study team and participants were informed of their group allocation after randomisation. Participants filled in questionnaires three times (four weeks, eight weeks, five months) after randomisation. Post-, and follow-up assessments also included a diagnostic telephone interview with interviewers blinded to the study condition. Participants were allowed to seek additional mental health support.

Online intervention SOPHIE

The eight-week online intervention SOPHIE is based the Cognitive Model of Social Phobia30 adapted to specific needs of adolescents29 and existing evidence-based online interventions for adults with SAD63,64,65,66,67,68,69. It consists of 8 modules41: introduction and goal setting, six modules dedicated to the maintaining mechanisms of the Cognitive Model30including negative automatic thought processing, self-focused attention, and avoidance and safety behaviour, and a final module with a short repetition and outlook. Adolescents were guided by trained and supervised graduate students in Psychology41. For more information of the development of the intervention and a detailed description of the modules, please consider the study protocol41.

Care-as-usual (CAU) control condition

Participants in the CAU group were only contacted regarding assessments and received access to SOPHIE after the follow-up assessment. They received no specific intervention and were free to access all kinds of support services. The use of other support services was assessed at post-assessment.

Materials

Primary outcome

The self-report scale Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN; original English version70; German version71) is an internationally used and recommended70 continuous measure assessing 3 dimensions of social anxiety (i.e., fear, avoidance, and physical symptoms). In each of the 17 items, symptoms of the past week are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (scored from not at all (0) to extremely (4); total range: 0–68)72. An example item is “I avoid talking to people I don’t know”. In adolescent samples, the SPIN has shown good psychometric properties to detect subthreshold and threshold SAD73,74 and demonstrated good test-retest reliability (r = 0.81) and internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.89)74 and evidenced good convergent and discriminant validity75. The SPIN value at post-assessment was defined as the primary outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Self-report measures

At baseline, mid-intervention, post-intervention and follow-up, general anxiety symptoms were assessed with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)76,77 depressive symptoms with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for Adolescents (PHQ-A)78 fear and avoidance with the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A)79,80 quality of life with the KIDSCREEN-1081, and self-esteem with the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSES)82.

The GAD-7 questionnaire (original English version83; German adolescent version76) measures self-reported frequency of anxiety symptoms with 7 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale scored from not at all (0) to nearly every day (3) (total range 0–21). An example item is “Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge”. In adolescents, the questionnaire has demonstrated good psychometric properties with good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.91) and construct validity77.

The PHQ-A (original adolescent English version78,84; German version85) assesses frequency of depressive symptoms over the last 2 weeks in adolescents with 9 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale from not at all (0) to nearly every day (3) (total range 0–27). A sample item is “Little interest or pleasure in doing things”. This self-report questionnaire shows good psychometric properties for detecting depression in adolescents78,84 and a pooled Cronbach’s α = 0.86 across the life-span86.

The SAS-A (original English version79; German version87,88) measures fear of negative evaluation and social avoidance in adolescents with 18 items answered on a 5-point Likert scale from not at all (1) to all the time (5) (total range 18–90). A sample item is “I worry about what others say about me“. The measure has shown good validity and reliability in both clinical and nonclinical samples and the internal consistency for the total scale was Cronbach’s α = 0.9179,80.

The KIDSCREEN assessments were simultaneously developed in different European countries and languages including German89. The KIDSCREEN-10 assesses health-related quality of life with 10 items answered on a 5-point Likert scale rated from never/not at all (1) to always/extremely (5) (total range 1–50). A sample item is “Have you felt fit and well?”. The scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties and reported a Cronbach’s α = 0.8281.

The RSES (original English version82; German version90) assesses self-esteem in 10 items on a Guttman scale rated from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (3) (total range 0–30). A sample item is: “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”. In this study the adolescent version of the questionnaire was used. This version has shown good psychometric properties with a Cronbach’s α = 0.8191.

Clinician-rated interviews

Adolescents were assessed for past and current mental disorders at baseline according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 with the Diagnostic Interview for Mental Disorders for Children and Adolescents(German: Kinder DIPS;)92,93. At post-intervention and follow-up, only the section for SAD and diagnoses met at baseline were assessed. Global functioning was assessed at baseline, post-intervention and follow-up with the Global Functioning Social and Role Scale, a structured interview yielding a score from 1 to 10 for each subscale94,95.

Adherence

Adherence was operationalised through the extent to which the online intervention was used. The number of finished modules, of completed exercises, and the time spent in the online intervention were recorded automatically.

Guardian report

If guardians provided their e-mail address, they rated their child’s social anxiety with the Parents’ Questionnaire on Social Anxieties in Childhood and Adolescence (German: Elternfragebogen zu sozialen Ängsten im Kindes- und Jugendalter (ESAK); range 0–54)96 at baseline, mid-treatment, post-intervention and follow-up.

Assessment of negative effects and satisfaction with intervention

Negative effects of the intervention were assessed post-intervention with the Inventory for recording negative effects in psychotherapy (INEP)97,98 and satisfaction with the intervention with the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8; mean value between 1–4)99.

Demographic information

Adolescents reported their age, gender, nationality, native language and living situation during the baseline telephone interview. Socioeconomic status was measured with the Social Affluence Scale (range 0–12)100,101. Guardians reported their level of education, employment status and living situation during their first assessment.

Qualitative interview

The qualitative assessment consisted of a semi-structured interview. The questions covered topics that were based on the stages adolescents move through when participating in an intervention study: awareness of their problems and of digital help, consideration of and expectations towards study participation, and experiences during the intervention102,103. Regarding the intervention, helpfulness of individual modules and experiences with guidance were explored. Questions were open-ended, but the interviewer could provide a structured scale (i.e., from very helpful to not at all helpful) as a starting point for a more detailed discussion. The final interview guide can be found in the supplementary material.

Analysis

Sample size

The initial sample size was determined in two a-priori analyses (SAD-group and subclinical group) for the primary research question in G*Power104 based on an intention-to-treat (ITT) approach and repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA). The analysis for the SAD group was based on small-to-moderate effect sizes (Cohen’s d =.35)105,106 and the analysis for the subclinical anxiety group on a small effect size (Cohen’s d =.20)47,107,108,109. We assumed an α-level of 5%, a power of 80%, and a correlation between measurements of r = 0.4. The targeted sample size was N = 222 including n = 56 adolescents with SAD and n = 166 adolescents with subclinical social anxiety.

As the targeted sample size for the entire sample and the subclinical anxiety group was not reached, post hoc power analyses were conducted using G*Power. The parameters matched those of the a priori analysis, with an alpha level of 5% and an assumed correlation between repeated measures of r = 0.40. For the main analysis (effect size d = 0.67, N = 133), the calculated power was 0.97. Similarly, the power was 0.99 for the SAD group (d = 1.21, n = 93) and 0.99 for the subclinical anxiety group (d = 1.53, n = 40).

Efficacy analysis

All participants were analysed using the ITT approach. Baseline differences were assessed with Chi-square tests for nominal data and independent t-tests for continuous data. Patterns of missingness in primary and secondary outcomes were visually inspected. The possible influence of demographic variables, study condition, and baseline assessments on missingness was analysed with Chi-square tests for binary predictors and logistic regressions for continuous predictors.

The primary outcome, difference of social anxiety symptoms between study groups at post-assessment, was analysed using linear mixed-effects models with restricted maximum likelihood estimation with the lmer function of the lme4 package110 in R (version 2023.12.1 + 402). Linear mixed-effects models were selected because they account for irregular assessment timepoints and dependencies in longitudinal data and provide unbiased estimates under the missing at random (MAR) assumption, using maximum likelihood estimation111,112,113. In the final model, time (baseline, mid-intervention, post-intervention), intervention condition (SOPHIE, CAU), and interactions were specified as fixed effects. Baseline SPIN value was added as a fixed covariate, and participant was included as a random effect to allow for between-person variation. The same model was used to analyse intervention effects on secondary outcomes (i.e., general anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, quality of life, self-esteem, and guardians’ rating of social anxiety). Follow-up effects were analysed using the same model with all four assessment timepoints included. The SPIN model for post- and follow-up effects was first computed with all participants and then separately in subgroup analyses with participants of the clinical group and the subclinical group. Remission of SAD diagnosis was only assessed in the clinical group, and Chi-square tests were used to compare intervention and control groups at post- and follow-up assessments.

Additionally, sensitivity analyses were performed for the primary outcome SPIN using a per-protocol sample. For the post-assessment model, the per-protocol sample (n = 77) included participants who completed all three assessment timepoints: baseline, mid-intervention, and post-intervention. For the follow-up model, participants (n = 57) had to complete all four timepoints: baseline, mid-intervention, post-intervention, and follow-up. We used the same models as described above for these analyses.

Qualitative data collection and analysis

The qualitative interview was conducted after the intervention with adolescents from the SOPHIE study group via telephone. Individual interviews were audio-recorded and afterwards transcribed verbatim. A reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) approach was chosen due to its flexibility to explore the full range of experiences and to account for subjectively perceived realities114,115. For this study, a contextualist standpoint was adopted, allowing us to interpret adolescents’ experiences within their social contexts. A reflexive, iterative analysis process was followed, where themes were co-constructed based on participant experiences, aiming for a nuanced understanding of central ideas and concepts114,116. Following the six steps of RTA, authors NW and DH familiarised themselves with the data and coded text parts that reflected experiences of participants during and with the intervention. Both authors discussed and reviewed initial codes to develop first possible themes. Subsequently, the full transcripts were re-coded with the identified themes and subthemes, leading to further adjustments to the themes. A thematic map was created and discussed with the research team. During the theme review process, we found that the interview data was not sufficiently rich to develop themes united by a central concept or idea that were not solely reflecting the topics of the interview guide. Thus, instead of overinterpreting or presenting underdeveloped themes115,117,118we focused on creating themes with a shared topic and common points expressed by participants in relation to this topic. This approach led to sub-domains of similar experiences, which we consolidated into domain summaries exploring different facets of each topic. Finally, both authors coded the transcripts again. Domains and sub-domains were exemplified with quotes from the transcripts using pseudonyms for quotation presentation. All quotes were translated from (Swiss) German and minimally altered to enhance clarity while preserving meaning.

Researcher reflexivity

Authors NW and DH conducted the analysis. NW led this RCT as part of her doctoral dissertation thereby providing extensive familiarity with the study and the SOPHIE programme. DH was a Psychology master student new to the project and exclusively handled qualitative data. Both approached the data inductively. Nonetheless, NW acknowledged that her involvement in the study might have influenced her perception of adolescents’ experiences with the intervention. Furthermore, the interviews were conducted by telephone without video conferencing. This way of data collection might have influenced the data richness; some adolescents provided only very brief responses, and even after probing further questions, they did not provide much more content. For adolescents with social anxiety, discussing personal experiences over the phone might be challenging, and for the interviewer, the lack of nonverbal cues may have influenced the understanding of their statements.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. Please contact Prof. Dr. Stefanie Schmidt: stefanie.schmidt@unibe.ch.

References

Solmi, M. et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry 2021 27:1 27, 281–295 (2021).

Jefferies, P. & Ungar, M. Social anxiety in young people: A prevalence study in seven countries. PLoS One. 15, 1–18 (2020).

Mörtberg, E., Jansson Fröjmark, M., Van Zalk, N. & Tillfors, M. A longitudinal study of prevalence and predictors of incidence and persistence of sub-diagnostic social anxiety among Swedish adolescents. Nord Psychol. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2021.1943498 (2021).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostisches Und Statistisches Manual Psychischer Störungen DSM-5. Washington DC, (2013).

Ranta, K., Aalto-Setälä, T., Heikkinen, T. & Kiviruusu, O. Social anxiety in Finnish adolescents from 2013 to 2021: change from pre-COVID-19 to COVID-19 era, and mid-pandemic correlates. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1, 1–16 (2023).

Goodwin, R. D., Weinberger, A. H., Kim, J. H., Wu, M. & Galea, S. Trends in anxiety among adults in the united states, 2008–2018: rapid increases among young adults. J. Psychiatr Res. 130, 441–446 (2020).

Aune, T., Nordahl, H. M. & Beidel, D. C. Social anxiety disorder in adolescents: prevalence and subtypes in the Young-HUNT3 study. J. Anxiety Disord. 87, 102546 (2022).

Asselmann, E., Wittchen, H. U., Lieb, R. & Beesdo-Baum, K. Sociodemographic, clinical, and functional long-term outcomes in adolescents and young adults with mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 137, 6–17 (2018).

Dryman, M. T., Gardner, S., Weeks, J. W. & Heimberg, R. G. Social anxiety disorder and quality of life: how fears of negative and positive evaluation relate to specific domains of life satisfaction. J. Anxiety Disord. 38, 1–8 (2016).

Fehm, L., Beesdo, K., Jacobi, F. & Fiedler, A. Social anxiety disorder above and below the diagnostic threshold: prevalence, comorbidity and impairment in the general population. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 43, 257–265 (2008).

Stein, D. J. et al. The cross-national epidemiology of social anxiety disorder: data from the world mental health survey initiative. BMC Med. 15, 1–21 (2017).

Chiu, K., Clark, D. M. & Leigh, E. Prospective associations between peer functioning and social anxiety in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 279, 650–661 (2021).

McGorry, P. D. & Mei, C. Early intervention in youth mental health: progress and future directions. Evid. Based Ment Health. 21, 182–184 (2018).

Ebert, D. D. et al. Internet and Computer-Based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: A Meta-Analysis of randomized controlled outcome trials. PLoS One. 10, e0119895 (2015).

Podina, I. R., Mogoase, C., David, D., Szentagotai, A. & Dobrean, A. A Meta-Analysis on the efficacy of technology mediated CBT for anxious children and adolescents. J. Ration. - Emotive Cogn. - Behav. Therapy. 34, 31–50 (2016).

Rooksby, M., Elouafkaoui, P., Humphris, G., Clarkson, J. & Freeman, R. Internet-assisted delivery of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for childhood anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 29, 83–92 (2015).

Hugh-Jones, S., Beckett, S., Tumelty, E. & Mallikarjun, P. Indicated prevention interventions for anxiety in children and adolescents: a review and meta-analysis of school-based programs. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 30, 849–860 (2021).

Clarke, A. M., Kuosmanen, T. & Barry, M. M. A systematic review of online youth mental health promotion and prevention interventions. J. Youth Adolesc. 44, 90–113 (2014).

Noh, D. & Kim, H. Effectiveness of online interventions for the universal and selective prevention of mental health problems among adolescents: a systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Prev. Sci. 24, 353–364 (2023).

Werntz, A., Amado, S., Jasman, M., Ervin, A. & Rhodes, J. E. Providing human support for the use of digital mental health interventions: systematic Meta-review. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e42864 (2023).

Liverpool, S. et al. Engaging children and young people in digital mental health interventions: systematic review of modes of delivery, facilitators, and barriers. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, 1–17 (2020).

Domhardt, M., Steubl, L. & Baumeister, H. Internet- and Mobile-Based interventions for mental and somatic conditions in children and adolescents. Z. Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 48, 33–46 (2018).

Lehtimaki, S., Martic, J., Wahl, B., Foster, K. T. & Schwalbe, N. Evidence on digital mental health interventions for adolescents and young people: systematic overview. JMIR Ment Health. 8, e25847 (2021).

Creswell, C., Waite, P., Hudson, J., Practitioner & Review Anxiety disorders in children and young people – assessment and treatment. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 61, 628–643 (2020).

Ginsburg, G. S. et al. Remission after acute treatment in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders: findings from the CAMS. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 79, 806–813 (2011).

Hudson, J. L. et al. Comparing outcomes for children with different anxiety disorders following cognitive behavioural therapy. Behav. Res. Ther. 72, 30–37 (2015).

Kodal, A. et al. Long-term effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for youth with anxiety disorders. J. Anxiety Disord. 53, 58–67 (2018).

Walder, N., Frey, A., Berger, T. & Schmidt, S. J. Digital Mental Health Interventions for Prevention and Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder in Children, Adolescents and Young Adults. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials, J. Medical Inter. Res., 27, e67067, (2025).

Leigh, E. & Clark, D. M. Understanding social anxiety disorder in adolescents and improving treatment outcomes: applying the cognitive model of Clark and wells (1995). Clin. Child. Fam Psychol. Rev. 21, 388–414 (2018).

Clark, D. M. & Wells, A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In Social Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment (eds Heimberg, R. G. et al.) 69–93 (Guilford Press, 1995).

Rapee, R. M. & Heimberg, R. G. A Cognitive-Behavioural model of anxiety in social phobia. Behav. Res. Ther. 35, 741–756 (1997).

Hofmann, S. G. Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: a comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 36, 193–209 (2007).

Wong, Q. J. J. & Rapee, R. M. The aetiology and maintenance of social anxiety disorder: A synthesis of complimentary theoretical models and formulation of a new integrated model. J. Affect. Disord. 203, 84–100 (2016).

Spence, S. H., Donovan, C. L., March, S., Kenardy, J. A. & Hearn, C. S. Generic versus disorder specific cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder in youth: A randomized controlled trial using internet delivery. Behav. Res. Ther. 90, 41–57 (2017).

Nordh, M. et al. Therapist-guided internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy vs internet-delivered supportive therapy for children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 78, 705–713 (2021).

Leigh, E. & Clark, D. M. Internet-delivered therapist-assisted cognitive therapy for adolescent social anxiety disorder (OSCA): a randomised controlled trial addressing preliminary efficacy and mechanisms of action. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1111/JCPP.13680 (2022).

Spillane, J. P. et al. Mixing methods in randomized controlled trials (RCTs): validation, contextualization, triangulation, and control. Educ. Assess. Eval Acc. 22, 5–28 (2010).

Midgley, N., Ansaldo, F. & Target, M. The meaningful assessment of therapy outcomes: incorporating a qualitative study into a randomized controlled trial evaluating the treatment of adolescent depression. Psychotherapy 51, 128–137 (2014).

Leigh, E., Nicol-Harper, R., Travlou, M. & Clark, D. M. Adolescents’ experience of receiving internet-delivered cognitive therapy for social anxiety disorder. Internet Interv. 34, 100664 (2023).

Dures, E., Rumsey, N., Morris, M. & Gleeson, K. Mixed methods in health psychology. J. Health Psychol. 16, 332–341 (2010).

Walder, N., Berger, T. & Schmidt, S. J. Prevention and treatment of social anxiety disorder in adolescents: protocol for a randomized controlled trial of the online guided Self-Help intervention SOPHIE. JMIR Res. Protoc. 12, e44346 (2023).

Kang, H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. J Educ. Eval Health Prof 18(17), 1–12 (2021).

Asbrand, J., Krämer, M., Heinrichs, N. & Nitschke, K. Tuschen-Caffier, and B. Cognitive behavior group therapy for children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder. Kindh. Entwickl. 32, 205–215 (2023).

Bai, S. et al. Anxiety symptom trajectories from treatment to 5- to 12-year follow-up across childhood and adolescence. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 64, 1336–1345 (2023).

Leigh, E., Chiu, K. & Clark, D. M. Self-focused attention and safety behaviours maintain social anxiety in adolescents: an experimental study. PLoS One. 16, e0247703 (2021).

de Mooij, B. et al. What works in preventing emerging social anxiety: exposure, cognitive restructuring, or a combination?? J. Child. Fam Stud. 32, 498–515 (2023).

Stockings, E. A. et al. Preventing depression and anxiety in young people: a review of the joint efficacy of universal, selective and indicated prevention. Psychol. Med. 46, 11–26 (2016).

Nagata, T., Suzuki, F. & Teo, A. R. Generalized social anxiety disorder: A still-neglected anxiety disorder 3 decades since liebowitz’s review. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 69, 724–740 (2015).

Zarger, M. M. & Rich, B. A. Predictors of treatment utilization among adolescents with social anxiety disorder. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 71, 191–198 (2016).

Jong, S. T., Stevenson, R., Winpenny, E. M., Corder, K. & van Sluijs, E. M. F. Recruitment and retention into longitudinal health research from an adolescent perspective: a qualitative study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 23, 1–13 (2023).

Bielinski, L. L., Trimpop, L. & Berger, T. [All in the mix? Blended psychotherapy as an example of digitalization in psychotherapy]. Psychotherapeut (Berl). 66, 447–454 (2021).

Maiuolo, M., Deane, F. P., Ciarrochi, J. P. & Authoritativeness Social support and Help-seeking for mental health problems in adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 48, 1056–1067 (2019).

De Los Reyes, A. et al. Informant discrepancies in clinical reports of youths and interviewers’ impressions of the reliability of informants. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 21, 417 (2011).

Ohannessian, C. M. C. De Los reyes, A. Discrepancies in adolescents’ and their mothers’ perceptions of the family and adolescent anxiety symptomatology. Parent. Sci. Pract. 14, 1 (2014).

Makol, B. A. et al. Integrating multiple informants’ reports: how conceptual and measurement models May address Long-Standing problems in clinical Decision-Making. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 8, 953–970 (2020).

Vilaplana-Pérez, A. et al. Much more than just shyness: the impact of social anxiety disorder on educational performance across the lifespan. Psychol. Med. 51, 861–869 (2021).

Pearl, S. B. & Norton, P. J. Transdiagnostic versus diagnosis specific cognitive behavioural therapies for anxiety: A meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 46, 11–24 (2017).

Eilert, N., Wogan, R., Leen, A. & Richards, D. Internet-Delivered interventions for depression and anxiety symptoms in children and young people: systematic review and Meta-analysis. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 5, e33551 (2022).

Berg, M. et al. The role of learning support and Chat-Sessions in guided Internet-Based cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with anxiety: A factorial design study. Front. Psychiatry. 11, 515935 (2020).

Szinay, D. et al. Influences on the uptake of health and well-being apps and curated app portals: Think-aloud and interview study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 9, e27173 (2021).

Tinner, L. E. et al. Qualitative evaluation of Web-Based digital intervention to prevent and reduce excessive alcohol use and harm among young people aged 14–15 years: A ‘Think-Aloud’ study. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 3, e19749 (2020).

Connor, K. M. et al. Psychometric properties of the social phobia inventory (SPIN). New self- rating scale. Br. J. Psychiatry. 176, 379–386 (2000).

Berger, T., Hohl, E. & Caspar, F. Internet-based treatment for social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychol. 65, 1021–1035 (2009).

Berger, T. et al. Internet-based treatment of social phobia: A randomized controlled trial comparing unguided with two types of guided self-help. Behav. Res. Ther. 49, 158–169 (2011).

Berger, T., Boettcher, J. & Caspar, F. Internet-based guided self-help for several anxiety disorders: A randomized controlled trial comparing a tailored with a standardized disorder-specific approach. Psychotherapy 51, 207–219 (2014).

Boettcher, J., Berger, T. & Renneberg, B. Does a pre-treatment diagnostic interview affect the outcome of internet-based self-help for social anxiety disorder? A randomized controlled trial. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 40, 513–528 (2012).

Kählke, F. et al. Efficacy of an unguided internet-based self‐help intervention for social anxiety disorder in university students: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr Res. 28, e1766 (2019).

Schulz, A. et al. A sorrow shared is a sorrow halved? A three-arm randomized controlled trial comparing internet-based clinician-guided individual versus group treatment for social anxiety disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 84, 14–26 (2016).

Stolz, T. et al. A mobile app for social anxiety disorder: A three-arm randomized controlled trial comparing mobile and PC-based guided self-help interventions. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 86, 493–504 (2018).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment and treatment of social anxiety disorder. 1–37 (2013). www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg159

Stangier, U. & Steffens, M. Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN)— Deutsche Fassung. Preprint at (2002).

Johnson, H. S., Inderbitzen-Nolan, H. M. & Anderson, E. R. The social phobia inventory: validity and reliability in an adolescent community sample. Psychol. Assess. 18, 269–277 (2006).

Sosic, Z., Gieler, U. & Stangier, U. Screening for social phobia in medical in- and outpatients with the German version of the social phobia inventory (SPIN). J. Anxiety Disord. 22, 849–859 (2008).

Ranta, K. et al. Age and gender differences in social anxiety symptoms during adolescence: the social phobia inventory (SPIN) as a measure. Psychiatry Res. 153, 261–270 (2007).

Johnson, H. S. & Inderbitzen-Nolan, H. M. The social phobia inventory: validity and reliability in an adolescent community sample. Psychol. Assess. 18, 269–277 (2006).

Löwe, B. et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med. Care. 46, 266–274 (2008).

Tiirikainen, K., Haravuori, H., Ranta, K., Kaltiala-Heino, R. & Marttunen, M. Psychometric properties of the 7-item generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7) in a large representative sample of Finnish adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 272, 30–35 (2019).

Richardson, L. P. et al. Evaluation of the patient health questionnaire-9 item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics 126, 1117–1123 (2010).

La Greca, A. M. & Lopez, N. Social anxiety among adolescents: linkages with peer relations and friendships. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 26, 83–94 (1998).

Olivares, J. et al. Social anxiety scale for adolescents (SAS-A): psychometric properties in a spanish-speaking population. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 5, 85–97 (2005).

Ravens-Sieberer, U. et al. Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: A short measure for children and adolescents’ well-being and health-related quality of life. Qual. Life Res. 19, 1487–1500 (2010).

Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale. J. Relig. Health. https://doi.org/10.1037/t01038-000 (1965).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1092–1097 (2006).

Johnson, J. G., Harris, E. S., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J. Adolesc. Health. 30, 196–204 (2002).

Allgaier, A. K., Pietsch, K., Frühe, B. & Sigl-Glöckner, J. Schulte-Körne, G. SCREENING FOR DEPRESSION IN ADOLESCENTS: VALIDITY OF THE PATIENT HEALTH QUESTIONNAIRE IN PEDIATRIC CARE. Depress. Anxiety. 29, 906–913 (2012).

Ajele, K. W. & Idemudia, E. S. Charting the course of depression care: a meta-analysis of reliability generalization of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ- 9) as the measure. Discover Mental Health. 5, 1–18 (2025).

Melfsen, S. & Walitza, S. Skalen Zur erfassung von angststörungen Im Kindes- und jugendalter. Klinische Diagnostik Und Evaluation. 3, 142–163 (2010).

Nicolay, P., Weber, S. & Huber, C. Überprüfung der Konstrukt-, Kriteriumsvalidität und Messinvarianz eines Instruments zur Messung von sozialer Unsicherheit. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000270 67, 126–136.

Ravens-Sieberer, U. et al. The European KIDSCREEN approach to measure quality of life and well-being in children: development, current application, and future advances. Qual. Life Res. 23, 791–803 (2014).

Von Collani, G. & Yorck Herzberg, P. Zur internen struktur des globalen Selbstwertgefühls Nach Rosenberg on the internal structure of global Self-Esteem (Rosenberg). Zeitschrift für Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychologie, 24, 9–22 (2003).

Whiteside-Mansell, L. & Flynn Corwyn, R. Mean and covariance structures analyses: an examination of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale among adolescents and adults. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 63, 163–173 (2003).

Margraf, J., Cwik, J. C., Pflug, V. & Schneider, S. Strukturierte Klinische Interviews Zur Erfassung Psychischer Störungen Über Die Lebensspanne (Hogrefe, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1026/1616-3443/A000430

Schneider, S., Pflug, V., In-Albon, T., Margraf, J. & Kinder Forschungs- und Behandlungszentrum für psychische Gesundheit (Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 2017). https://doi.org/10.13154/rub.101.90-DIPS Open Access: Diagnostisches Interview Bei Psychischen Störungen Im Kindes- Und Jugendalter.

Cornblatt, B. A. et al. Preliminary findings for two new measures of social and role functioning in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 33, 688–702 (2007).

Carrión, R. E. et al. The global functioning: social and role scales-further validation in a large sample of adolescents and young adults at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 45, 763–772 (2019).

van Gemmeren, B., Bender, C., Pook, M. & Tuschen-Caffier, B. Elternfragebogen zu sozialen Ängsten Im Kindes- und jugendalter (ESAK): entwicklung, psychometrische qualität und normierung. Klinische Diagnostik Und Evaluation. 14, 412–429 (2008).

Bieda, A. et al. Unwanted side effects in children and youth psychotherapy – introduction and recommendations. PPmP Psychother. Psychosom. Medizinische Psychologie. 68, 383–390 (2018).

Ladwig, I., Rief, W. & Nestoriuc, Y. What are the risks and side effects of psychotherapy? – Development of an inventory for the assessment of negative effects of psychotherapy (INEP). Verhaltenstherapie 24, 252–263 (2014).

Schmidt, J., Lamprecht, F. & Wittmann, W. W. Fragebogen Zur Messung der patientenzufriedenheit. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 39, 248–255 (1989).

Hobza, V., Hamrik, Z., Bucksch, J., Clercq, B. & De The family affluence scale as an indicator for socioeconomic status: validation on regional income differences in the Czech Republic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 14, 1540 (2017).

Torsheim, T. et al. Psychometric validation of the revised family affluence scale: a latent variable approach. Child. Indic. Res. 9, 771–784 (2016).

Doshi, A., Connally, L., Spiroff, M., Johnson, A. & Mashour, G. A. Adapting the buying funnel model of consumer behavior to the design of an online health research recruitment tool. J. Clin. Transl Sci. 1, 240–245 (2017).

Kleinjohann, M. & Reinecke, V. Marketingkommunikation Mit der generation Z. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-30822-3

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 39, 175–191 (2007).

Christ, C. et al. Internet and Computer-Based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e17831 (2020).

Grist, R., Croker, A., Denne, M. & Stallard, P. Technology delivered interventions for depression and anxiety in children and adolescents: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Child. Fam Psychol. Rev. 22, 147–171 (2019).

Feiss, R. et al. A systematic review and Meta-Analysis of School-Based stress, anxiety, and depression prevention programs for adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 48, 1668–1685 (2019).

Werner-Seidler, A., Perry, Y., Calear, A. L., Newby, J. M. & Christensen, H. School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 51, 30–47 (2017).

Dray, J. et al. Systematic review of universal Resilience-Focused interventions targeting child and adolescent mental health in the school setting. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 56, 813–824 (2017).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear Mixed-Effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Singer, J. D. & Willette, J. B. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence (Oxford University Press, 2003).

Raudenbush, S. W. & Bryk, A. S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods (Sage Publications, Inc., 2002).

West, B. T., Welch, K. B. & Galecki, A. T. Linear Mixed Models A Practical Guide Using Statistical Software (CRC, 2022).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101 (2006).

Clarke, V. & Braun, V. Using thematic analysis in counselling and psychotherapy research: A critical reflection. Couns. Psychother. Res. 18, 107–110 (2018).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health. 11, 589–597 (2019).

Connelly, L. M. & Peltzer, J. N. Underdeveloped themes in qualitative research: relationship with interviews and analysis. Clin. Nurse Specialist. 30, 51–57 (2016).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Is thematic analysis used well in health psychology? A critical review of published research, with recommendations for quality practice and reporting. Health Psychol. Rev. 17, 695–718 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ingrid Odermatt and Noé Weigl for their contributions to programming the online intervention SOPHIE and Stefan Kodzhabashev for his technology support. Further, we like to thank all involved master students, Janin Ambühl, Lisa Dasen, Lena Demel, Loris Di Ponzio, Alessja Frey, Laura Imboden, Fabrice Leuzinger, Chantal Messerli, Elina Mombelli, Elisabeth Pauly, Elinor Sager, Elena Schoch, Claudia Tachezy, and Pascale Zürcher, for their help with recruitment and data collection. We would also like to thank Anja Hirsig, Xenia Häfeli and Alessja Frey for co-creating the qualitative interview guide and Alessja Frey for conducting the qualitative interviews.

Funding

The Division of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology and the Division of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, University of Bern, Switzerland provided funding for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Noemi Walder: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Project Administration; Thomas Berger: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Reviewing & Editing, Supervision; Dominique Hürzeler: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – Reviewing & Editing; Emily McDougal: Writing – Reviewing & Editing; Julian Edbrooke-Childs: Writing – Reviewing & Editing; Stefanie J Schmidt: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Reviewing & Editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Walder, N., Berger, T., Hürzeler, D. et al. Prevention and treatment of social anxiety disorder in adolescents: mixed method randomised controlled trial of the guided online intervention SOPHIE. Sci Rep 15, 25141 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10193-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10193-w