Abstract

The present paper proposes an algorithmic model, MASW-YOLO, that improves YOLOv8n. This model aims to address the problems of small targets, missed detection, and misdetection of UAV viewpoint feature detection targets. The backbone network structure is enhanced by incorporating a multi-scale convolutional MSCA attention mechanism, which introduces a deep convolution process to aggregate local information. This method aims to increase small-target detection accuracy. Concurrently, the neck network structure is reconstructed, with the fusion effect of multi-scale weakening of non-adjacent levels addressed by using an AFPN progressive pyramid network to replace the PANFPN structure of the base model. The MSCA and AFPN form a multiscale feature synergy mechanism, whereby the response values of MSCA become inputs to AFPN, and the multiscale integration of AFPN further amplifies the advantages of MSCA. The use of flexible non-maximum suppression Soft-NMS is chosen to replace the non-maximum suppression NMS to improve the model’s detection of occlusion and dense targets. The loss function of the model is optimised through the implementation of Wise-IoU, which serves as a replacement for the loss function of the baseline model, thereby enhancing the accuracy of bounding box regression, especially perform better when the target deformation or scale change is large. Experiments conducted on the VisDrone2019 dataset demonstrate that the average detection accuracy of the MASW-YOLO algorithm is 38.3%, which is augmented by 7.9% through the utilisation of the original YOLOv8n network. Furthermore, the number of network parameters is reduced by 19.6%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent years have seen unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology experience rapid development, resulting in an expansion of its application fields and an increase in the diversity of its functionalities. These devices have found applications in civil, transportation1 and military domains, underscoring their growing importance. The flexibility and mobility of UAVs provide significant advantages over traditional visual devices and offer a broad range of potential applications. The utilisation of drones has the potential to facilitate the execution of perilous tasks. In the event of a disaster, the deployment of drone detection technology can expedite the comprehension of the situation on the scene, thereby enhancing the efficacy of rescue operations. Furthermore, the potential applications of drone detection technology extend to the domains of traffic monitoring, military operations, and the tracking of live sporting events. The significance of drone detection technology is indisputable.

The emergence of deep learning target detection approaches has resulted in a variety of detection models, the most common of which are single-stage and two-stage. The two-stage model is designated a two-step detector and is characterised by its increased computational demands, in addition to its capacity for high detection accuracy. Conversely, single-stage models, also designated as one-step detectors, do not necessitate the generation of candidate regions. They achieve quicker inference speeds and frame rates while maintaining a given degree of accuracy. Consequently, in scenarios where resources are limited, single-stage models can also achieve satisfactory performance. In contrast, the single-stage model is more appropriate for UAV target detection, including the SDD2 algorithm, the YOLO3,4 series of algorithms, and so forth. Among these, YOLO has become the most widely used target detection model through continuous updating, iteration and development.

Whilst the integration of UAV imagery with target detection algorithms to facilitate automatic target detection offers certain advantages, it is also confronted with significant challenges, primarily including the following:

-

(1)

The capacity to detect targets of minimal size. In the context of UAV-perspective detection targets, which are characterised by their densely arranged nature and small size, the convolutional layer of the deep learning model exhibits a limited sensory field. This limitation results in the underutilisation of spatial features, thereby hindering the effective detection of small targets.

-

(2)

It is vital to understand that UAV hardware resources are restricted. It is imperative to ensure the number of network parameters is adequate, in conjunction with the requisite detection accuracy. This necessitates a multifaceted approach, wherein the optimization of effects is pursued while maintaining equilibrium.

-

(3)

Dense object occlusion problem. UAVs are shooting at high altitude, there are a substantial of occlusion situations, and the occluded objects are often unrecognisable, thereby compromising the efficacy of the underlying algorithm.

In order to surmount these challenges, an increasing number of researchers are concentrating their efforts on the detection of small targets. Existing small target detection algorithms have been shown to demonstrate sub-optimal performance in a number of scenarios, including those involving sensory fields, insufficient feature fusion and dense occlusion. Furthermore, these algorithms are not capable of reducing the model’s complexity to a satisfactory degree. To address the key issues in target detection from a UAV perspective, this study introduces MASW-YOLO, an algorithm based on the YOLOv8n model for UAV viewpoint feature detection, enhancing target detection accuracy while ensuring model efficiency. The following are the principal contributions of this paper:

1) The efficacy of the Multi-Scale Convolution Attention (MSCA)5 attention mechanism in enhancing the detection of small targets has been demonstrated. The features of different sensory fields are captured by parallel multi-scale convolutional kernels, which are dynamically weighted in combination with the channel attention mechanism to enhance the model’s ability to perceive multi-scale targets. The deep convolution operation has been demonstrated to enhance local detail extraction, with a particular emphasis on small target regions. The issue of feature weakening in small targets due to low resolution is resolved, and the detection accuracy of targets of various sizes (particularly small objects) is enhanced.

2) Reconstruct the neck network through the AFPN module. Form a multi-scale collaborative mechanism with MSCA. The traditional PAN + FPN6 is replaced by the Asymptotic Feature Pyramid Network (AFPN)7. The combination adopts a hierarchical progressive feature fusion technique to improve the interaction of non-adjacent hierarchical features, as well as the completeness and flexibility of multi-scale feature fusion. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the AFPN forms a multiscale feature synergy mechanism with MSCA, whereby the response value of MSCA becomes the input of AFPN, and the multi scale feature fusion of AFPN further amplifies the advantages of MSCA.

3) The efficacy of target occlusion detection can be enhanced by incorporating the Soft Non-Maximum Suppression (Soft-NMS)8 module. This approach addresses the challenge of low target occlusion detection accuracy in complex scenarios. In the NMS stage, the Soft-NMS module employs confidence attenuation as opposed to direct exclusion for boxes that overlap with the box of highest score, thereby ensuring the retention of potential targets. It has been demonstrated that using this strategy greatly enhances target occlusion detection performance in high-density scenarios.

4) The loss optimisation with Wise Inter section over Union (Wise-IoU)9 involves the substitution of the original Completing Inter section with CIoU10 in YOLOv8 with finer geometric constraints. Additionally, the Wise-IoU loss function dynamically adjusts the regression weights. This results in accelerated convergence of the model and enhanced accuracy of the bounding box prediction, particularly in cases where target deformation or scale change is significant.

Background and related works

Deep learning has accelerated the development of target identification methods based on this cutting-edge learning theory, which have been used in a number of image detection domains. It is evident that considerable attention has been focused on the YOLO algorithm.

Introduction to the YOLO algorithm

Recent years have seen the YOLO series of algorithms undergo continuous updates, reaching the 12th generation. YOLOv811 has achieved significant advancements in target detection, establishing an optimized equilibrium between computational efficiency and recognition precision. Its performance is particularly notable in practical applications across various domains.

The YOLOv8 model retains the scaling factor concept of YOLOv5 and is divided into five versions: YOLOv8n, YOLOv8s, YOLOv8m, YOLOv8l, and YOLOv8x. The versions differ in the width and depth of the network, with the n to x versions becoming more complex.Targeting resource-constrained aerial systems, our methodological enhancements concentrate on YOLOv8n, the most algorithmically lean implementation in the YOLOv8 family. The YOLOv8n model is composed of three components: the backbone, the neck, and the header network, which consists of three-scale decoupled output prediction layers. The backbone extracts features through convolutions, C2f, and SPPF12. The neck integrates FPN and PAN multi-scale features13. The detection head of YOLOv8 employs two branches to extract information through two 3 × 3 convolutions and one 1xl convolution, respectively. This contributes to increasing the breadth and depth of feature extraction, which raises the robustness and accuracy of detection.

Related work

Many scientific advances have been made in the field of target detection in recent years. In the domain of remote sensing image processing, Qian14 et al. proposed a UTS strategy to provide a generic solution for HOD to OOD BBR loss migration. They also proposed FRIoU loss on top of RIoU loss to improve the detection accuracy while optimizing the training process by dynamically weighting the samples. Furthermore, Qian15 et al. proposed two novel methods, Complete Pseudo Soft Labeling (CPSL) and Invariant Multi-Instance Learning (IMIL), with the aim of resolving issues pertaining to neighbouring instances misclassification and error accumulation, respectively, in the domain of Weakly Supervised Object Detection (WSOD). These methods were then combined with affine transformation to enhance the model’s resilience and achieve SOTA performance in remote sensing WSOD tasks.

In the field of UAV image detection, Xue16 et al. refined the UAV image target detection algorithm YOLOv7-drone, building upon YOLOv7-tiny. They enhanced the feature fusion mechanism within the network and augmented the accuracy of small target detection by incorporating a novel small target detection layer. Chen17 et al. proposed a target detection algorithm, YOLO, that improves the YOLOv8 _RC, which achieved some performance improvement while the number of parameters decreased. Boshra Khalili18 et al. proposed SOD-YOLOv8, inspired by efficient GFPNs, which enhances multipath fusion in YOLOv8 to improve the performance of the model. Pan19 et al. proposed a BDC-YOLOv8 detection model that incorporates a dedicated detection head for small targets, incorporating the CBAM attention mechanism to improve the detection accuracy. Dong20 et al. demonstrated an improved Cross-YOLO algorithm to make an enhanced version of YOLOv8, proposing to enhance the FPN by Cross-FPN to improve the detection accuracy. Zhu21 et al. implemented the CBAM attention mechanism in YOLOv5s with a view to resolving the issue of detecting blurred images from the perspective of an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Lyu22 et al. optimized feature fusion at different scales by modifying the neck network structure of YOLOv8.

In the domain of safety detection, Li23 et al. proposed an algorithm that combines three fundamental techniques: the use of GD for feature extraction, the modification of the detection head, and the optimization of the loss function to improve the speed and precision of deep forest fire detection. Jiao24 et al. employed a migration learning strategy for the labeling and training processes, which resulted in a substantial enhancement in the accuracy of helmet detection, a crucial aspect in ensuring the personal safety of workers.

In the domain of medical image processing, Sun25 et al. proposed SSW-YOLO to improve the detection performance of blood cells. Tan26 et al. presented LymoNet, a cervical lymph node detection algorithm that utilises an advanced attention mechanism module to achieve SOTA performance, offering a highly promising solution.

The deep learning models in each of the aforementioned domains are designed for small target detection, and all have been enhanced in terms of accuracy. However, the performance of the detection algorithm is subject to certain limitations. In the case of a single image detection target, the full potential of the detection algorithm cannot be realised, resulting in a limited effect. Furthermore, when confronted with complex backgrounds and small targets, the anticipated performance is not achieved, thereby reducing the robustness of the model in practical applications. Moreover, the restricted resources available to the UAV platform present a challenge in achieving a lightweight model that retains accuracy. Consequently, further research and enhancement of these limitations are imperative. These limitations motivate the proposal of the MASW-YOLO algorithm, which improves detection accuracy while keeping the model line-weighted.

Methodology

MASW-YOLO model

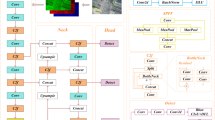

This paper’s objective is to enhance the efficacy of small target detection from the perspective of a UAV. Additionally, it seeks to address the challenges of false and missed detection. The following paper sets out a proposal for an improved MASW-YOLO model based on YOLOv8n, in view of the characteristics of small target detection under UAV viewpoint. As demonstrated in Fig. 1, the network structure is illustrated. Firstly, the detection accuracy of small targets is enhanced by fusing the MSCA attention mechanism to strengthen the local detail extraction, with a particular focus on small target regions. Secondly, the neck network is reconstructed to form a multiscale feature synergy mechanism. The neck network adds the AFPN, which encourages direct feature fusion between non-adjacent layers. The AFPN overcomes the multiscale weakening of the non-adjacent layers’ fusion effect and establishes a multiscale feature synergy mechanism with MSCA. The response value of the MSCA becomes the input of the AFPN, and the multiscale feature fusion of the AFPN further amplifies the advantages of the MSCA. It is evident that the detection accuracy of occluded objects is enhanced by the flexible non-extremely large value suppression Soft-NMS module. In this module, candidate frames that overlap with the highest scoring frames are subjected to confidence attenuation rather than direct elimination in the NMS stage. Consequently, some potential targets are retained. Finally, the WIoU is used to replace YOLOv8’s original CIoU loss function, with the goal of improving flexibility to detection targets with varying dimensionalities and morphologies.

Multi-scale convolution attention mechanism

In addressing the challenges posed by the UAV viewpoint feature detection target’s limited size and the presence of occlusions, effective feature information extraction is paramount to enhance the detection performance. In this study, we suggest enhancing the network structure by including the MSCA mechanism into the backbone network design, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

MSCA employs a large convolutional kernel decomposition and a multi-branch parallel architecture, thereby ensuring the MSCA attention mechanism’s capacity to capture multi-scale targets and aggregate multi-scale channel information27.

The MSCA attentional mechanism enhances features through a three-fold structure. First, depth-separable convolution efficiently integrates local area features. Second, the parallel multi-scale strip convolution module extracts contextual semantic information across the sensory field by decomposing both horizontally and vertically. Finally, the point-by-point convolution layer establishes cross-channel feature associations, thereby realizing efficient interactions and weight assignments of the channel dimensions. Initially, MSCA performs convolutional operations on each channel of the input feature map through 5 × 5 convolutional kernels, thus capturing spatial dimensional feature information. Thereafter, the convolved information of each channel is fused, allowing the information of each channel to be aggregated. Subsequently, these convolved channel information are fused. The employment of a deep convolution design has been demonstrated to be an effective method of reducing the number of total parameters in the network model. Furthermore, it has been shown to skillfully realise the separation of channel and spatial information through the strategy of feature extraction in the spatial dimension first and then integrating the information of each channel, while maintaining the number of channels of the feature map unchanged.

Secondly, multi-branch deep strip convolution28 simulates the traditional n × n standard 2D convolution through multiple branches, each using convolution kernels of different sizes 1 × n and n × 1. In addition, stripwise convolution improves the detection of small targets by extracting stripwise features that may be missed by mesh-like convolution, enabling the model to capture more contextual information at different scales. Furthermore, the employment of smaller convolution kernels ensures the maintenance of lightweight computation.

Finally, 1 × 1 point-by-point convolution is used to model the relationship between different channels in the feature. The output of this process is then employed as the weighting of the convolutional attention, with the purpose of re-weighting the inputs of the MSCA. This technique helps to focus the model’s attention on relevant elements.

It can be described by a mathematical formula as:

where F denotes the input features, Att and Out denote the attention map and output, respectively. \(\otimes\)is an element-by-element matrix multiplication operation, DW-Conv denotes deep convolution, and Scalei (i∈{0,1,2,3}) denotes the ith branch in Fig. 2.

Asymptotic feature pyramid network

The structure of the Progressive Pyramid Network (AFPN) is illustrated in Fig. 3. The black arrow denotes the convolution operation, while the cyan arrow indicates the adaptive spatial feature fusion.AFPN employs a step-by-step incremental approach to integrate different levels of features in the feature extraction process of the Backbone network29. Specifically, AFPN first processes the bottom-level features, then gradually introduces the middle-level features, and finally fuses the high-level abstract features. The significant semantic dissimilarity between the features at each level, most pronounced between the bottom layer and the high-level features, suggests that direct overall fusion of multi-layer features, such as C2, C3, C4 and C5, may result in suboptimal fusion outcomes. Consequently, the direct fusion scheme is deemed suboptimal. The AFPN’s step-by-step fusion design, however, has been shown to effectively bridge the semantic gap between features of different layers. To illustrate this, the semantic information of C2 and C3 is first integrated, thereby bringing their semantic information closer together. Subsequently, the semantic information of C3 and C4 is amalgamated, thus reducing the semantic discrepancy between C2 and C4. The layer-by-layer progressive fusion approach enhances semantic consistency, thereby improving the fusion effect and detection performance. This progressive feature fusion method has significant advantages in mitigating the differences in semantic information at non-adjacent levels, optimising the feature integration capability of the pyramid network, and providing higher-quality multiscale feature characterisation for subsequent tasks.

The AFPN is comprised of the following modules: the Convolutional Block (CB), the Basic Block (BB), and the Adaptive Spatial Fusion (ASFF)30. The CBS module’s job is to slice and extend the input feature maps in channel dimensions, hence enhancing the model’s sensory field and successfully retrieving feature map information. This method enhances target detection performance. The BasicBlock module lightens the model and minimizes the number of parameters, allowing it to perform feature extraction more efficiently. The ASFF module, i.e. the adaptive spatial fusion operation, fuses multiple feature maps of different layers. The AFPN module has been shown to be capable of capturing multi-scale information more effectively by dynamically selecting and fusing multiple layers of feature maps. At the same time, it is able to inhibit information contradiction between features at different levels, thereby improving the effectiveness of feature fusion and the robustness and accuracy of the model in complex scenes.

Soft non-maximum suppression module

In the context of target detection, an algorithm is employed to generate one or more detection borders for designated object classes within an image. These borders are then used to classify and score the objects within their respective confines. Conventional object detection methods characteristically employ a multi-scale sliding window technique to traverse the image and compute feature scores for each window, thereby distinguishing between foreground and background31. However, this approach is hindered by a significant drawback: the high correlation between neighbouring windows. This results in a high rate of false positives in the detection results. To address this issue, the NMS is commonly used in the post-processing stage by filtering out bounding boxes with large overlapping regions and low confidence, thus retaining the boxes that are most likely to contain the target object. While NMS is effective in reducing false alarms, it can, however, excessively hinder effective detection when confronted with scenarios involving dense occlusion or multiple targets in close proximity, particularly when two high-quality but partially overlapping target frames are erroneously removed due to overlap, resulting in missed detections.The NMS score reset function is depicted in Eq. (3):

In the context of the UAV viewpoint feature detection task, the occurrence of omission and false detection due to target occlusion is a prevalent phenomenon. In order to address this issue, the present paper replaces the traditional NMS algorithm in the baseline model with flexible non-maximal suppression (Soft-NMS).Soft-NMS dynamically processes the scores according to the degree of overlap of the neighbouring detection frames by adjusting the score decay mechanism instead of simply setting the scores of the overlapping frames to zero directly32. Specifically, when the overlap region between a certain detection frame and a high-quality detection frame (denoted as M) is large, its score is drastically cut down; while when the overlap region is small, its score has less impact, thus retaining the detection results more flexibly.

This methodology enables enhanced control of the detection outcomes and mitigates the occurrence of missed detections due to over-suppression.The Soft-NMS score reset function is delineated in Eq. (4):

In this equation, ‘si’ denotes the variance of the decay function, ‘Nt’ is the threshold for adjusting the decay function, and ‘iou (µ, bi)’ is the intersection and juxtaposition ratio of the true and predicted frames. The traditional score adjustment function may cause the score mutation problem due to discontinuity when reaching the non-maximal inhibition threshold. To address this challenge, a Gaussian penalty function is incorporated into the optimization process. The Gaussian penalty mechanism is such that when the candidate box does not overlap at all with the highest-scoring box M, there will be no cut in its score; and as the overlap increases, the penalty is gradually increased so as to achieve smooth score adjustment. The incorporation of the smoothing property of the Gaussian function ensures a more continuous and gradual change in penalty strength with overlap degree, thereby effectively preventing the occurrence of score disconnection. The modified score reset function is shown in Eq. (5):

As demonstrated in Fig. 4 and as indicated in Eq. 5, Soft-NMS is comprised of three adjustable parameters, namely the threshold coefficient (Nt), the score reduction coefficient (si), and the score threshold (score). It is evident that the variation of these parameters has a substantial impact on the performance of Soft-NMS in diverse tasks.

WIoU loss function

The YOLOv8 network utilises a prediction method to calculate the edge coordinate loss LCIoU33 (see Eqs. 6–9). This calculation is performed using the CIoU, which is determined as outlined in the following Eq.

The location is defined by the following: α is a weighting function that is utilised to balance the importance of differing samples or targets, with the objective of more accurately measuring the model performance. v is an aspect ratio metric function that is employed to measure the aspect ratio consistency.

The CIoU loss function has been demonstrated to improve the model’s ability to mimic the target’s shape by including a corrective factor34. It also takes into account the target frame’s diagonal distance, increasing the accuracy of the target detection model in localizing the target.The CIoU loss function effectively speeds the convergence of prediction frame regression by using the bounding box’s aspect ratio as an extra penalty term in the loss computation. However, when the projected frame’s aspect ratio is linearly related to the real frame, it may lead to unsynchronized adjustment of the width and height in the regression process. This paper introduces WIoU to replace the CIoU loss function. WIoU mitigates the width-height inconsistency problem that occurs during the regression process through a more flexible focusing method, thus improving the accuracy and stability of the box regression.The WIoU is calculated as shown in Eq. (10) :

In Eq. (10), the distance focusing mechanism RWIoU is employed to amplify the LIoU of the ordinary modest anchor frame with RWIoU ∈ [1,e), which will significantly increase the value of LIoU. Conversely, the non-monotonic focusing coefficient r, on the other hand, is employed to adjust the degree of focusing of the common mass anchor frame as a parameter that regulates the degree of matching of the predicted frame with the real labeled frame. Unlike monotonic focusing coefficients, non-monotonic focusing coefficients allow dynamic adjustment of the degree of matching over a range of different IoU values, resulting in a more fine-grained assessment of model performance.RWIoU35 is defined as in Eq. (11) and r is defined as shown in Eq. (12):

where β is the outlier degree and\(\mathop {LIoU}\limits^{ - }\)denotes the dynamic sliding average, when the dynamic sliding average is large, it may lead to slow parameter updating, making the results of the bounding box regression overly conservative, making it difficult to adapt to changes in the position of the detection target, and leading to the detection frame deviating from the true position of the detection target.

In instances where the dynamic sliding average is minimal, there is a possibility that the parameter update will become excessively sensitive. This, in turn, can result in significant fluctuations in the results of the bounding box regression, thereby causing the detection frame to fluctuate around the target. Consequently, this can lead to an inability to accurately capture the precise position of the target. It is therefore vital to select an appropriate dynamic sliding average in order to maintain the accuracy and stability of the detection frame and ensure that the bounding box can regress to the location of the target with precision. It is also important to note that α and δ are used as hyper-parameters, and that adjusting these hyper-parameters can improve the performance and generalisation ability of the model.

Experimental

Datasets

The experiment under consideration is trained using the VisDrone201936 dataset, the object types and size distributions of which are illustrated in Fig. 5.

The VisDrone2019 dataset is a target detection dataset from the viewpoint of a UAV produced by a team from Tianjin University and other teams.The dataset was collected with a UAV under different conditions, including the number of how many, the complexity of the background environment, the daytime and nighttime, as well as the number of species.The dataset represented by the different conditions of VisDrone2019 is shown in Fig. 6.

Source: The photographs originate from the VisDrone2019(https://github.com/VisDrone/VisDrone-Dataset).

Representative image of VisDrone2019.

The VisDrone201936 dataset contains targets of various sizes, which are categorized into 10 distinct categories. Among the aforementioned targets, pedestrians, bicycles, and motorcycles can be considered as relatively vulnerable. The primary targets are vehicles such as cars and trucks.The training set has 6,471 images, the validation set has 548 images, and the test set has 1,610 images.

Experimental platform and environment configuration

The Windows 10 operating system was utilized as the experimental platform. The central processing unit (CPU) model employed was the AMD Ryzen 5 560oG Radeon Graphics model, and the graphics card w the NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1660 SUPER, featuring 16GB of video memory. Environment configuration: Python version 3.8, torch version 1.12.0, cuda version 11.3.

The input image size is 640 × 640, the number of training rounds is 100, and the single image input batch is set to 16. The experimental parameter setting table is shown in Table 1.

Evaluation indicators

The evaluation metrics employed for this experiment include the number of parameters (Params/M), model calculations (FLOPs/G), Precision, mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5–95, and the number of parameters, in order to assess the performance of the model.

Precision rate is calculated as presented in Eq. (13).

The accuracy rate is initiated from the prediction result, where Tp is delineated as the instance being a positive sample predicted to be a positive sample, and Fp is delineated as the instance being a negative sample predicted to be a positive sample.

The formula for the average accuracy of each type is presented in Eq. (14), where N is the number of types of detected targets.

Ablation experiment results and analysis

The present section of the ablation experiment was meant to validate each module’s contribution in order to determine the success of the MASW-YOLO improvement process. The present study employed an ablation experiment on the VisDrone2019 dataset, with"” denoting the incorporation of a refined segment. The data pertaining to the ablation experiment is displayed in Table 2.

After the baseline model was updated to include the MSCA attention mechanism, the mAP@0.5 metric demonstrated a notable enhancement, rising from 30.4 to 30.9%. Similarly, the mAP@0.5–0.95 metric exhibited an improvement, increasing from 17.4 to 17.8%. Additionally, there was an augmentation in the number of parameters, which rose from 3.01 million to 3.10 million. This finding suggests that the MSCA module captures the characteristics of different receptive fields through the multi-scale convolutional kernel, thereby enhancing the model’s multi-scale target perception, including the perception of small targets. This makes it easier to improve local detail features and improve the model’s detection accuracy.

The utilisation of both MSCA and AFPN modules results in an enhancement of mAP@0.5 from 30.4 to 30.5%, and in an increase of mAP@0.5–0.95 from 17.4 to 17.6%. Concurrently, Params undergoes a reduction from 3.01 M to 2.42 M. The application MSCA is located at the end position of the backbone network, which is connected to the neck network. The positional structure of these two forms a feature processing pipeline, with the refined feature output of MSCA becoming the input of AFPN. The multi-scale integration of AFPN further amplifies the advantages of MSCA. In instances where the implementation of the AFPN asymptotic pyramid network mAP@0.5 value does not yield enhancements, but rather exhibits a decline in performance that defies intuitive expectations, separate experimental investigations have consistently demonstrated that the training outcomes consistently surpass those of the baseline model when the training number is 150.

Following the integration of Soft-NMS with the MSCA and AFPN modules, there was an observed enhancement in performance metrics. Specifically, the mAP@0.5 increased from 30.4 to 37.7%, while the mAP@0.5–0.95 rose from 17.4 to 24.3%. Concurrently, the parameter size was reduced from 3.01 M to 2.42 M. The incorporation of Soft-NMS has been demonstrated to improve the model’s ability to detect small targets and reduce the occlusion issue caused by missed detections, thereby markedly enhancing detection accuracy.

The employment of the MSCA, AFPN, Soft-NMS, and WIoU modules in unison, otherwise designated as the MASW-YOLO algorithm, has been demonstrated to enhance the mAP@0.5 value by 7.9%, the mAP@0.5–95 value by 7.1%, the accuracy rate by 12.9%, the Recall by 1.7%, the FLOPs by 1.0G, and the Params by 0.59 M by 19.6%.The WIoU loss function has been shown to be instrumental in enhancing the detection accuracy. A comparison of the MASW-YOLO model’s characteristics to those of the benchmark model demonstrates considerable gains in target detection accuracy, scene adaptation, and robustness from the perspective of an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV).

Comparison of ablation experiment visualization

To facilitate the intuitive assessment of the detection outcomes of the enhanced algorithm, the findings from the ablation experiments are presented in a visual format and subjected to comparative analysis, as depicted in Fig. 7. The initial three columns (a), (b), and (c) of Fig. 7 present the detection result plots of the original image, the enhanced MSCA model, and the enhanced AFPN model, respectively. The second columns (d), (e), and (f) present the detection result plots of the enhanced Soft-NMS model, the enhanced WIoU model. The first column shows the improved MSCA + AFPN model, and the third columns (g), (h), and (i) present the detection result plots of the improved MSCA + AFPN + Soft-NMS model, the YOLOv8n model, and the detection result plots of the MASW-YOLO model, respectively.

Source: The photographs originate from the VisDrone2019(https://github.com/VisDrone/VisDrone-Dataset).

Comparison images of ablation experiments.

As illustrated in Fig. 7, the visualised images of all the ablation experiments are presented for analysis. As can be discerned from the original image (a), the scene is depicted as being situated in a city street, which is characterised by a high degree of congestion. The lower right quadrant of the original image is demarcated by a red circle, indicating an automobile obscured by a tree. The vehicle is not detected in figure (h), yet it is identified by the benchmark model in figures (d), (g), and (i). This illustrates the impact of the ablation experiments in a more intuitive manner. Furthermore, the enhanced model exhibits a reduced incidence of miss detection in instances of occlusion. The lower right corner of the figure (h) detected by the benchmark model misidentifies the occluded object as a bicycle, while the remaining models do not misidentify the object. This more intuitively demonstrates the advantages of MASW-YOLO. As demonstrated by the visualization images obtained from the ablation experiment, MASW-YOLO exhibits performance superior to that of the baseline model with respect to both missed detections and misdetections in the occlusion case. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated to exhibit proficiency in detecting small targets within the viewing angle and demonstrates notable robustness.

Comparative experiments

The efficacy of the enhanced algorithm outlined in this paper was assessed through a comparative analysis of the algorithm model in this paper and the prevailing YOLO series algorithms. These included YOLOv5n37, YOLOv7_tiny38, YOLOv8n11, YOLOv9t, YOLOv10n39, YOLOv11n40, and the recently released YOLOv12n41. The comparatives was conducted using the Visdrone2019 dataset. The SSD algorithms were also compared, with experimental results presented in Table 3; Fig. 8.

An analysis of the test results indicates the performance differences of different algorithms. Firstly, the SSD algorithm demonstrates a slightly lower detection accuracy in comparison to the YOLO algorithm. In addition, the FPS is only 39, which prevents real-time detection and indicates suboptimal performance. The most classic YOLOv5n algorithm has a performance mAP@0.5 of 29.3%, which responds to one of the difficulties of the YOLO algorithm in target detection in the UAV viewpoint, with lower detection accuracy. In the subsequent analysis, the YOLOv7_tiny algorithm demonstrated a performance mAP@0.5 of 27.1 and Params of 6.02 M. This result indicates a lower detection accuracy in comparison to the YOLOv5n algorithm and a higher number of network parameters. The YOLOv5n algorithm, however, exhibits superior performance metrics in this regard.

We then proceeded to analyse the more advanced YOLOv8n, YOLOv9t, and YOLOv10n algorithms. In this analysis, YOLOv8n, as an early release of the YOLO series, outperformed the other algorithms in all detection metrics, with a mAP@0.5 of 30.The YOLOv8n network demonstrates a superior performance in target detection under UAV viewpoint, as evidenced by its higher accuracy of 4%, surpassing all other algorithms examined. This superiority is further accentuated by its reduced number of network parameters, which is a notable advantage over other networks. Consequently, this paper has been selected to enhance its performance based on the YOLOv8n network algorithm.

The most advanced algorithm models at present are YOLOv11n and YOLOv12n, with the latter being the latest series released this year. The performance of the YOLOv11 algorithm is indicated by a mAP@0.5 of 29.1% and Params of 2.58 M, while the performance of the YOLOv12 algorithm is indicated by a mAP@0.5 of 28.5% and Params of 2.52 M. As a newly released algorithm model, its detection accuracy on the VisDrone2019 dataset is somewhat lacking.

Finally, the MASW-YOLO model demonstrates a strong advantage in terms of detection accuracy, achieving an mAP@0.5 of 38.3% and an mAP@0.5–0.95 of 24.5%. It is also notable that the parameter count is maintained at 2.42 M. This finding indicates that MASW-YOLO exhibits superior performance in comparison to all other algorithms, while concurrently preserving the lightweight nature of the model. This attribute confers a distinct advantage in practical applications. In addition, the improved model has an FPS of 107.5 frames, which is 40.3 frames lower than the benchmark model, and is lower than many of the latest algorithm models, but still has a higher FPS, has relatively high real-time, and can be applied to practical applications.

To further illustrate the efficiency of the present algorithm, two state-of-the-art models from the extant literature are selected for comparison, namely PSO-YOLO42 and YOLO-S3DT43. As demonstrated in Table 4; Fig. 9.

The experimental results demonstrate that the performance of the PSO-YOLO algorithm is 30.9% for mAP@0.5 and 17.4% for mAP@0.5–0.95, while the performance of the YOLO-S3DT algorithm is 37.9% for mAP@0.5 and 21.1% for mAP@0.5–0.95. It is evident that both models demonstrate superior performance in terms of detection accuracy when compared to the established benchmark model, particularly the YOLO-S3DT model, which exhibits a notable enhancement of 7.5% in mAP@0.5. Furthermore, a reduction in the number of parameters is observed, with a decrease of 14.0% and 2.7% in the parameters of both. In comparison with the preceding YOLO series, both have enhanced detection accuracy and performance in the UAV view. However, both of these algorithms demonstrate inferior performance in comparison to MASW-YOLO, which exhibits a 7.4% and 0.4% increase in mAP@0.5, respectively, and possesses a reduced parameter count. The findings demonstrate the superior performance of the MASW-YOLO algorithm.

Data analysis of detection types

To facilitate a more intuitive understanding ofthe advantages of the improved model, please refer to Table 5; Fig. 10, which show the detection results of the baseline model and MASW-YOLO for each category.

As demonstrated by the table and bar charts, MASW-YOLO exhibits superior performance in detecting mAP@0.5 for all target categories when compared to the baseline model. The findings of the enhanced model for each category demonstrate that the model has considerably elevated the detection accuracy for diminutive targets such as pedestrians, bicycles, and motorcycles. For instance, the mAP@0.5 value for pedestrians has been augmented from 31.5 to 36% in the baseline model. The findings indicate that the enhanced model demonstrates superior resilience in scenarios involving smaller targets. Furthermore, the capacity to detect vehicle targets has been enhanced, with the highest mAP@0.5 value recorded at 72.6% for the car class. The following presentation will demonstrate the performance of the detection system when applied to the automobile class. In summary, the MASW-YOLO model demonstrates superior performance in target detection across all categories when compared to the established benchmark. This outcome serves to substantiate the efficacy of the enhanced algorithm employed.

Visualization and comparison of test results

In order to further explore the improvement effect of the MASW-YOLO model and to visualise the comparison in the test set of VisDrone2019, this paper selects two sets of images of a bright scene and a dim scene, and compares the detection effect of YOLOv8n with that of MASW-YOLO. The results are displayed in Fig. 11, wherein Fig. 11(a) and (b) depict the images of bright and dark scenes, respectively, Fig. 11(c) and Fig. 6(d) illustrate the recognition effect of the baseline model in bright and dim scenes, and Fig. 11(e) and Fig. 11(f) demonstrate the recognition effect of MASW-YOLO in bright and dim scenes.

Source: The photographs originate from the VisDrone2019(https://github.com/VisDrone/VisDrone-Dataset).

Comparison results chart.

As demonstrated in Fig. 11, the detection image from the bright scene reveals that the lower right corner is more dense, with a significant number of motorized vehicles and bicycles parked. Notably, the baseline model failed to detect the bicycles among them, while the MASW-YOLO model successfully identified them. As evidenced by the detection images under low-light conditions, the benchmark model erroneously identifies the tractor in the center of the road as a bicycle and failed to identify the motorcycle. In contrast, our enhanced algorithm successfully detects the motorcycle in the upper left corner. A comparison of the figures reveals that the proposed algorithm in this paper outperforms the benchmark algorithm in terms of leakage and misdetection of small objects from the UAV perspective. Furthermore, the majority of the confidence levels are higher than those of the benchmark algorithm.

Conclusion

The present study proposes an enhanced UAV viewpoint target detection algorithm, termed MASW-YOLO, which is based on YOLOv8n. This algorithm addresses the challenges posed by the detection of small target objects and partial occlusion in UAV viewpoint feature detection. The efficacy of the proposed algorithm is demonstrated by its ability to enhance the capability of UAV viewpoint feature detection through the incorporation of a multi-scale convolutional MSCA attention mechanism, the modification of the network structure of necking network by using an asymptotic pyramidal network AFPN, the replacement of the non-maximum suppression NMS of the baseline model with a flexibly non-extremely large value suppression Soft-NMS, and the optimization of the loss function. The experimental results demonstrate that the MASW-YOLO algorithm exhibits superior performance in the detection and localization of feature targets in comparison to the YOLOv8n algorithm. In comparison with the YOLOv8n, the model enhances the average accuracy mAP@0.5 by 7.9%. Moreover, the MASW-YOLO algorithm is more practical due to the creation of a lightweight model, which facilitates its application in UAVs with limited resources.

Notwithstanding the advances made in the model, there remains a necessity for continuous optimisation and enhancement. The following research areas have been identified as priorities for future study:

-

(1)

The model is subject to continuous optimization. A continuous comparison should be made between the improved model and the latest algorithmic model. In addition, further innovations should be mined with the aim to optimize the model and improve its performance.

-

(2)

It is imperative to improve the model’s capability for generalisation. The operational scope of UAVs is extensive, and the geometry and dimensions of the targets detected within their field of view exhibit significant variability. Consequently, the primary objective is to improve the model’s generalizability, allowing for larger use in practical contexts.

Data availability

All the images and experimental test images in this paper were from the open source VisDrone datasets. These datasets analyzed during the current research period can be found on the following website. Visdrone: (https://github.com/VisDrone/VisDrone-Dataset).

References

Di Feng, C. et al. Deep multi-modal object detection and semantic segmentation for autonomous driving: datasets, methods, and challenges [J]. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 22 (3), 1341–1360 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. SSD: Single shot MultiBoxdetector[C]//Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Springer InternationalPublishing, : 21–37. (2016).

A F. Joseph Redmon. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. ArXiv2018[J]:1804.02767.

Chen, Q. et al. You only look one-level feature[C]// IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), : 13034–13043. (2021).

Wang, S. & Xu, Y. MI-YOLO: an improved traffic sign detection algorithm based on YOLOv8[J]. Eng. Lett. 32 (12), 2336–2345 (2024).

Mei, S. et al. Research on fabric defect detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv8n algorithm [J]. Electronics 13 (11), 2009. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13112009 (2024).

Chen, H. & Tao, J. Utilizing improved YOLOv8 based on SPD-BRSA-AFPN for ultrasonic phased array non-destructive testing [J]. Ultrasonics 142, 107382 (2024).

Bodla, N. et al. Soft-NMS—im-proving object detection with one line of code[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. : 5561–5569. (2017).

Wang, G. et al. UAV-YOLOv8: A Small-Object-Detection model based on improved YOLOv8 for UAV aerial photography Scenarios[J]. Sensors 23(16), 7190 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. An Improved Target Detection Method Based on YOLOv5 in Natural Orchard environments[J]219108780 (Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2024).

Ultralytics Yolov8: The latest iteration of yolo for object detection. (2023). https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (Accessed 20 December 2023).

Jingwen, H. et al. A Small-Target forest fire smoke detection model based on deformable transformer for End-to-End object detection[J]. Forests 14 (1), 162–162 (2023).

Jiang, B. et al. Acquisition of localization confidence for accurate object detection [C]// Proceedings of the 2018 European conference on computer vision (ECCV). Munich, Germany, Springer, : 784–799. (2018).

Qian, X. et al. Building a Bridge of Bounding Box Regression Between Oriented and Horizontal Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images, in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 61, pp. 1–9, Art no. 5605209, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2023.3256373

Qian, X., Wang, C., Wang, W., Yao, X. & Cheng, G. Complete and Invariant Instance Classifier Refinement for Weakly Supervised Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images, in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 62, pp. 1–13, Art no. 5627713, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2024.3408895

Xue Shan, A., Hongyu, L., Qiongying, C. & Guohua Image target detection algorithm based on YOLOv7-tiny in complex background[J]. Infrared Laser Eng. 53 (1), 20230472. https://doi.org/10.3788/IRLA20230472 (2024).

Chen, H. Y. et al. Target detection algorithm for UAV aerial photography based on improved YOLOv8s[J]. Electro-Optics Control. 31 (12), 55–63 (2024).

Khalili, B. & Smyth, W. A. SOD-YOLOv8—Enhancing YOLOv8 for small object detection in aerial imagery and traffic Scenes[J]. Sensors 24 (19), 6209–6209 (2024).

Small Object Detection in Aerial Drone Imagery based on YOLOv8. Junyu Pan; Yujun Zhang.IAENG International Journal of Computer Science. (2024).

Dong, Y., Guo, J. & Xu, F. Cross-YOLO: an object detection algorithm for UAV based on improved YOLOv8 model[J]. Signal. Image Video Process. 19 (6), 489–489 (2025).

Zhu, X., Lyu, S., Wang, X. & Zhao, Q. Tph-yolov5: Improved yolov5 based on transformer prediction head for object detection on drone-captured scenarios. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 2778–2788 (2021).

Lyu, Y. et al. LightUAV-YOLO: a lightweight object detection model for unmanned aerial vehicle image[J]. J. Supercomputing. 81 (1), 105–105 (2024).

Li, C. et al. YOLOGX: an improved forest fire detection algorithm based on YOLOv8[J]. Front. Environ. Sci. 12, 1486212–1486212 (2025).

Jiao, X. et al. Detection method for safety helmet wearing on construction sites based on UAV images and YOLOv8[J]. Buildings 15 (3), 354–354 (2025).

Sun, H. et al. SSW-YOLO: enhanced blood cell detection with improved feature extraction and Multi-scale Attention[J]. J. Imaging Inf. Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-025-01460-3 (2025).

Tan, M. et al. LymoNet: an advanced neck lymph node detection network for ultrasound Images.[J]. IEEE J. Biomedical Health Inf., 29(3), 2125–2135 (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Robust image inpainting forensics by using an Attention-Based feature pyramid Network[J]. Appl. Sci. 13(16), 9196 (2023).

Li, Q. et al. Three-dimensional dynamic monitoring of crevasses based on deep learning and surface elevation reconstruction methods[J]. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 132, 104017 (2024).

Yang, G. et al. AFPN: asymptotic feature pyramid network for object detection[C]//2023 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC). IEEE, : 2184–2189. (2023).

Peng, Z., Zhang, C. & Wei, W. Leather defect detection based on improved YOLOv8 Model[J]. Appl. Sci. 14 (24), 11566–11566 (2024).

Feng, D. et al. Position information encoding FPN for small object detection in aerial images[J]. Neural Comput. Appl. 36 (26), 16023–16035 (2024).

Zhou, B., Wu, K. & Chen, M. Detection of Gannan navel orange ripeness in natural environment based on YOLOv5-NMM[J]. Agronomy 14 (5), 910 (2024).

Luo, Z. & Tian, Y. Improved infrared road object detection algorithm based on attention mechanism in YOLOv8[J]. IAENG Int. J. Comput. Sci. 51 (6), 673–680 (2024).

Zheng, Z. H. et al. Enhancing geometric Fac-tors in model learning and inference for object detection and instance Segmentation[J]. IEEE Trans. Cybernetics. 52 (8), 8574–8586 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. An improved YOLOv8 model for Lotus seedpod instance segmentation in the Lotus pond Environment[J]. Agronomy 14 (6), 1325–1325 (2024).

Zhu, P. et al. Detection and tracking Meet drones Challenge[C]/. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. 44, 7380–7399 (2021).

Ultralytics, Y. 5. (2020). https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5 (Accessed 15 March 2023).

Wang, C. Y., Bochkovskiy, A. & Liao, H. Y. M. Yolov7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proc. of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 7464–7475 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. BRA-YOLOv10: UAV small target detection based on YOLOv10[J]. Drones 9 (3), 159–159 (2025).

Zhou, S. et al. A lightweight drone detection method integrated into a linear attention mechanism based on improved YOLOv11[J]. Remote Sens. 17 (4), 705–705 (2025).

Ultralytics & YOLO12. : Détection d’objets centrée sur l’attention. https://docs.ultralytics.com/fr/models/yolo12, (2025). accessed on Mar. 02.

Zhao, Z., Liu, X. & He, P. PSO-YOLO: a contextual feature enhancement method for small object detection in UAV aerial images. Earth Sci. Inf. 18, 258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12145-025-01780-6 (2025).

Gao, P. & Li, Z. YOLO-S3DT: A small target detection model for UAV images based on YOLOv8[J]. Computers Mater. Continua. 82 (3), 4555–4572 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Anhui Province Key Research Program Project (No. 202304a05020049).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, M.X.H. ; Methodology, M.X.H.;Software, M.X.H.; Validation, M.X.H.; Formal analysis, M.X.H.; Investigation, M.X.H.;Resources, M.X.H.; Data curation, M.X.H.; Writing—original draft, M.X.H.; Writing—review& editing, M.X.H.and Z.D.X.;Supervision, Y.F. and Z.D.X.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, X., Yuan, F. & Zhang, D. Improved model MASW YOLO for small target detection in UAV images based on YOLOv8. Sci Rep 15, 25027 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10428-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10428-w