Abstract

High-altitude environments, can significantly impact cognitive functions, yet the neural mechanisms underlying altitude-induced changes in face recognition remain largely unexplored. This study aimed to examine the impact of high-altitude hypoxia on face recognition processes, with a specific focus on the modulation of the face inversion effect in event-related potentials across different altitude levels. A total of 120 participants were recruited and divided into four groups based on altitude: 347 m (low-altitude control), 2950 m, 3680 m, and 4530 m (high-altitude groups), with 30 participants in each group. Electroencephalography (EEG) was used to record brain activity, and event-related potentials components (P1 and N170) were analyzed to assess the effects of altitude on face processing, particularly regarding the face inversion effect. A significant altitude-dependent reduction in P1 amplitude was observed, with the 3680 m and 4530 m groups showing significantly lower amplitudes compared to the 347 m group (p < 0.05), and inverted faces elicited greater P1 amplitudes than upright faces (p = 0.035). N170 amplitude was significantly more negative for inverted faces compared to upright faces (p < 0.001), while the 4530 m group exhibited earlier N170 latencies than the other altitude groups (p < 0.05), suggesting possible neural adaptation to chronic hypoxia. The sLORETA results revealed progressive temporal lobe reorganization: the 4530 m group exhibited enhanced activation in superior temporal gyrus during inverted face processing, contrasting with diminished responses at moderate altitudes (3680 m). These findings provide neurophysiological evidence that high-altitude hypoxia significantly modulates face recognition processes, particularly the face inversion effect. The observed altitude-dependent alterations in ERP components suggest that hypoxia impacts both early sensory encoding (P1) and higher-order configural processing (N170).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-altitude environments (typically > 2,500 m) present a unique set of physiological and psychological challenges due to hypobaric hypoxia, extreme aridity, temperature fluctuations, and intense ultraviolet radiation1,2. Among these stressors, reduced oxygen availability is particularly critical, as it directly impacts cerebral metabolism and neurovascular function. Functional magnetic Resonance Imaging studies have demonstrated that hypoxia preferentially impairs prefrontal cortex activity3 a region responsible for cognitive control and resource allocation. As a result, hypoxia exposure has been linked to deficits in executive functions, including impaired working memory, slowed attentional shifting, and reduced decision-making efficiency1,4,5. While these cognitive impairments have been well-documented, less is known about how high-altitude stressors influence specialized perceptual processes that require substantial cognitive resources, such as face recognition.

Human face recognition relies on holistic integration, a perceptual mechanism that combines featural (eye shape) and configural (spatial relationships between features) information into unified representations1,2. This process is supported by a right-lateralized neural network, including the fusiform face area (FFA), occipital face area (OFA), and superior temporal sulcus (STS), which demonstrate heightened sensitivity to upright faces6,7,8. The face inversion effect9 provides a robust behavioral marker of holistic processing: when a face is presented upside-down, its configural information is disrupted, resulting in significantly reduced recognition accuracy10. Neurophysiological studies have shown that this inversion effect is reflected in event-related potential (ERP) components such as P1 and N170. The P1 component (~ 80–120 ms), generated in the extrastriate cortex, is sensitive to low-level visual properties and has been shown to increase in amplitude for inverted faces11. The N170 component (~ 150–190 ms), localized to the occipitotemporal cortex, is a well-established index of face perception and exhibits both amplitude enhancement and delayed latency for inverted faces, reflecting increased processing difficulty12,13,14.

Critically, holistic face processing depends on sufficient cognitive resources, making it susceptible to hypoxia-induced metabolic constraints15. Under conditions of cognitive resource depletion, face processing strategies may shift from holistic to featural analysis16 yet it remains unclear how this shift is modulated by increasing hypoxic severity. While studies have established the neural markers of holistic processing, little research has directly examined how altitude-related physiological stress affects the integrity of this mechanism.

This study aims to investigate the impact of high-altitude environments on holistic face processing by analyzing ERP components associated with face inversion. Specifically, we examine whether increasing altitude amplifies the face inversion effect, as reflected in N170 amplitude and latency differences between upright and inverted faces. Additionally, given its sensitivity to early-stage visual processing, P1 is included as a secondary measure to assess whether altitude-related effects extend to lower-level perceptual stages. We hypothesize that hypoxia will impair holistic processing, leading to a more pronounced inversion effect at higher altitudes, with N170 showing increased amplitude and delayed latency for inverted faces. These findings will provide novel insights into how environmental stressors shape high-level perceptual processes, advancing our understanding of cognitive adaptability in extreme conditions.

Method

Participants

A total of 120 male participants were recruited using convenient cluster sampling from plateau and plain areas. The participants were divided into four groups based on their altitude of residence: three experimental groups (plateau groups 1, 2, and 3) from plateau areas with altitudes of 2950 m (n = 30), 3680 m (n = 30), and 4530 m (n = 30), and a control group from a plain area at an altitude of 347 m (n = 30). The inclusion criteria for the plateau groups were as follows: (1) participants were born in a low-altitude area (< 500 m) before being stationed at their current altitude, and (2) they had lived continuously in the current high-altitude area for 16 to 18 months. Research has shown that individuals living at high altitudes for approximately 16–18 months exhibit stable adaptation in physiological and cognitive performance, with minimal impacts on cognitive function up to this point17. Exclusion criteria for the plateau groups included prior experience at high altitudes before their current stationing or any return to low-altitude areas during their stay. The inclusion criterion for the control group was that both the birthplace and stationing area were at low altitudes, with the exclusion criterion being prior exposure to high-altitude environments.

These criteria ensured that all participants had been continuously exposed to either high or low altitudes for an adequate period, allowing the body to acclimatize and minimizing the potential confounding effects of intermittent altitude exposure. The participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 24 years, and all were healthy, right-handed, with normal or corrected-to-normal vision, a normal body mass index, and no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders. A summary of the demographic characteristics of the participants is presented in Table 1. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the Drug Clinical Trial Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Air Force Military Medical University.

Stimuli and experimental setup

The stimuli used in this experiment consisted of processed real photographs, all with dimensions of 300 × 360 pixels (screen resolution: 800 × 600 pixels). The stimuli were categorized into three types: upright faces (60 images, 30 male and 30 female, with neutral expressions, and no crowns, hair, or other distracting features), inverted faces (60 images, 30 male and 30 female, with neutral expressions, and no crowns, hair, or other distractions), and upright face sunflowers (60 images, depicting various frontal views of sunflowers). The facial images used in this study were sourced from the CAS-PEAL Face Database18,19 a publicly available dataset designed for face recognition research. The database includes a diverse set of facial expressions, lighting conditions, and accessories to ensure variability in stimuli.

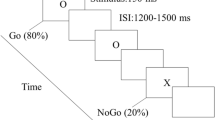

Participants were seated in a comfortable, controlled experimental environment, with limited background noise and appropriate lighting. The stimuli were displayed on a computer screen positioned approximately 75 cm from the participant, with a visual angle of 4° × 4°. The presentation of stimuli was controlled using E-prime 3.0 software. The experiment was divided into three parts, with participants first completing 12 practice trials before proceeding to the formal trials. In each part, stimuli were presented in a random order, ensuring that each type of stimulus appeared in equal proportions. The three sections included 100, 101, and 100 trials respectively, with the second section containing one additional sunflower trial. In each section, upright faces, inverted faces, and sunflower images were presented in an approximate 2:2:1 ratio. Rest periods were systematically incorporated, controlled by the participant’s response keys, to minimize fatigue effects during the experiment. The experimental protocol of this study is shown in Fig. 1. In each trial section, a 1000 ms blank screen was presented first, followed by a 1000 ms “+” gaze point in the centre of the screen in 28-point font, then a 1000 ms blank screen wherein the official test begins. The stimulus images were presented for 300 ms in each trial, followed by a blank screen for 800 ms. Subjects were asked to count the sunflower pictures and press a key to respond at the end of each trial section, asking to ignore stimuli other than the sunflower.

The experimental protocol used in our study. Note: Example of facial stimuli used in the experiment. Images were obtained from the CAS-PEAL Face Database19.

EEG recording and preprocessing

Brain electrical activity was recorded from 32 channels using a modified 10–20 system with an Ag/AgCl electrode cap (Neuroscan Inc.). A forehead electrode was used as the ground, and the tip of the nose served as the reference for recording. The EEG signals were continuously sampled at 1,000 Hz with a left mastoid reference and a forehead ground. A bandpass filter (0.1–70 Hz) was applied to amplify the EEG signals. The vertical electrooculogram (EOG) was recorded using electrodes placed above and below the left eye, while the horizontal EOG was recorded with electrodes placed lateral to both eyes. All electrode impedances were maintained below ten kΩ to ensure high-quality data.

EEG data preprocessing was carried out using EEGLAB software (2013, San Diego, USA), an open-source MATLAB-based toolbox (R2013b, MathWorks, United States). The preprocessing procedure included referencing the data to the bilateral mastoids, applying a bandpass filter with a low cutoff of 0.5 Hz and a high cutoff at 30 Hz. The EEG was then segmented from − 200 ms to 600 ms relative to stimulus onset, with the baseline period set as the first 200 ms. To correct for eye movement artifacts, independent component analysis (ICA) was applied, and components corresponding to eye movements were removed based on their specific activation patterns. Additional artifact rejection was performed using an amplitude threshold of 100 µV and a gradient criterion of (± 80) µV. The remaining valid trials were recomputed to a common average reference and averaged across trials for each participant.

For ERP analysis, the peak latency and average amplitude of the relevant components were extracted. The time windows for the two ERP components, P1 and N170, were set as follows: P1 (80–150 ms) and N170 (150–200 ms). Based on EEG topography and previous studies, the components were selected from the T5 and T6 electrode sites located in the temporo-occipital region.

Electrical source imaging

N170 evoked by inverted face conditions was source localisation. The sLORETA/eLORETA package (http://www.uzh.ch/keyinst/loreta.htm) will be used to calculate intracerebral electrical sources underlying the EEG activity recorded at the scalp20. This tool represents the cortex as a collection of volume elements (6239 voxels, size 5 mm × 5 mm × 5 mm). sLORETA is restricted to the cortical grey matter, hippocampus and amygdala in the digitised Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates corrected to the Talairach coordinates. Neuronal activity was computed as the current density (µA/mm2) without assuming a predefined number of active sources. Scalp electrode coordinates on the MNI brain were based on the international 5% system21. The sLORETA algorithm was used to solve the inverse problem by assuming the related orientations and strengths of neighbouring neuronal sources (represented by adjacent voxels). sLORETA has been proven to be an efficient tool for functional mapping because it is consistent with physiology and can correct localisation. In addition, the sLORETA localisation properties have been independently validated22. Non-parametric randomisation statistic was performed using the sLORETA non-parametric mapping tool. The sLORETA non-parametric mapping tool was used to perform between-group comparisons. In more detail, the sLORETA current density distribution was performed using statistical analysis based on the voxel-by-voxel log of the F ratio test with 5000 randomisations. Significant activations at the exceedance proportion tests with p < 0.05, F value over two z-score and a minimum cluster of voxels were higher than those calculated for each Broadmann area (BA) within a hemisphere.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (Version 23.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was employed to assess the normality of the data distribution for each group. For the amplitude and latency values of each ERP component, a three-way mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with the following factors: 4 (groups: 347 m, 2890 m, 3760 m, and 4530 m) × 2 (hemispheres: left T5, right T6) × 2 (face direction: upright face and inverted face). The significance level was set at 0.05 for all statistical analyses. For post hoc testing of significant main effects, the least significant difference method was used. In addition, simple effects analysis was conducted to examine significant interactions. The Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied to adjust for violations of the sphericity assumption in the ANOVA where appropriate. Effect size was reported for all ANOVA analyses using partial eta-squared (η2p). In this context, η2p values of 0.05, 0.10, and 0.20 were interpreted as representing small, medium, and large effects, respectively. Abbreviations used in the statistical analyses include M (mean, the average value of a set of data), SE (standard error, the standard deviation of the sampling distribution of the sample mean), and CL (confidence limits, the range of values within which the true population parameter is expected to lie with a certain level of confidence).

Results

EPR

The ERP waveform and topographic maps of the four elevations are shown in Fig. 2. P1 was quantified as the peak amplitude between 80 and 150 ms onset. A 4 (group: 347, 2950, 3680 and 4530 m) × 2 (face direction: upright and inverted) × 2 (hemispheres: left and right) combined with ANOVA was conducted for the peak amplitude of P1. The results revealed a significant main effect of groups,F (3, 102) = 2.839, p = 0.042, η2p = 0.639; the peak amplitude of P1 was more positive for the 347 m group (M = 3.422 µv, SE = 0.33 µv, 95% CL [2.77 4.08]) and the 2950 m group (M= 3.412 µv, SE = 0.36 µv, 95% CL [2.69 4.13]) than for the 3680 m group (M = 2.347 µv, SE = 0.32 µv, 95% CL [1.70 2.99]). The main effect of the face direction was also significant, F (1, 102) = 5.818, p= 0.035, η2p = 0.049; P1 was more positive for the inverted face (M = 3.316 µv, SE= 0.20 µv, 95% CL [2.75 3.53]) than for the upright face (M = 2.816 µv, SE= 0.14 µv, 95% CL [2.49 3.15]), p = 0.035. The main effect of hemisphere was also significant, F (1, 102) = 14.918, p < 0.000, η2p = 0.14; P1 was more positive for the right hemisphere (M = 3.412 µv, SE = 0.22 µv, 95% CL [2.99 3.84]) than for the left hemisphere (M = 2.54 µv, SE= 0.19 µv, 95% CL [2.17 2.91]), p < 0.000. No significant interaction effect was found between group and face direction(F (3, 102) = 1.216, p = 0.308, η2p = 0.037), group and hemisphere(F (3, 102) = 0.52, p = 0.669, η2 = 0.016), face direction and hemisphere (F (1, 102) = 0.249, p = 0.619, η2p = 0.003) or group as well as face direction and hemisphere(F (3, 102) = 1.527, p = 0.213, η2p = 0.046).

The ERP and topographic maps for inverted and upright faces across 347 m, 2950 m, 3680 m, and 4530 m regions. This figure illustrates the event-related potential (ERP) waveforms recorded from different regions in response to upright and inverted face stimuli. Each panel represents the averaged ERP waveforms for one of the four regions of interest.

Three-way mixed ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of the group on the latencies of P1, F (3, 102) = 7.68, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.19. The post-hoc test indicated that the latency of P1 at the 2950 m group was significantly earlier than the 3680 m (p = 0.039) and 4530 m (p < 0.001) groups. The analysis also revealed significant interaction effects between the group and trial type, F (3, 102) = 3.67, p = 0.015, η2p = 0.10. Simple effect analysis showed significant differences between the 4530 m group in the upright face and inverted face conditions. Further analysis revealed that P1 was evoked significantly earlier for the upright face than for the inverted face, p = 0.006.

N170 was quantified as the peak amplitude between 150 ms and 200 ms onset. A 4 (group: 347 m, 2950 m, 3680 m, and 4530 m) × 2 (face direction: upright and inverted) × 2 (hemispheres: Left and right) mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the amplitude of N170. The main effect of face direction was significant, F (1, 102) = 23.009, p < 0.000, η2p = 0.213; N170 was more negative for inverted face (M = −4.576 µv, SE = 0.33 µv, 95% CL [−5.24 −3.92]) than for upright face (M = −3.761 µv, SE = 0.34 µv, 95% CL [−4.45 −3.08]), p < 0.000. The results also revealed a significant main effect of hemisphere, F (1, 102) = 29.685, p < 0.000, η2p = 0.259; N170 was more negative for right hemisphere (M = −4.99 µv, SE = 0.39 µv, 95% CL [−5.76 −4.22]) than for left hemisphere (M = −3.34 µv, SE = 0.33 µv, 95% CL [−4.01 −2.68]), p < 0.000. There was no significant main effect of group, F (3, 102) = 1.903, p = 0.135, η2p= 0.656). There was also no significant interaction effect between group and face direction F (3, 102) = 0.916, p = 0.695, η2 = 0.015), group and hemisphere, F (3, 102) = 0.590, p = 0.623, η2p = 0.018), face direction and hemisphere, F (1, 102) = 0.143, p = 0.706, η2p = 0.002) or group, face direction and hemisphere, F (3, 102) = 0.051, p = 0.985, η2p = 0.002).

A three-way mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the latency of 170. The main effect of face direction was significant, F (1, 102) = 186.49, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.028, that inverted face evoked a later N170 compared to upright face. The main effect of groups was also significant, F (3, 102) = 4.45, p = 0.006, η2p = 0.12. The post-hoc test suggested the latency of N170 in the 4530 m group was significantly earlier than that in 347 m (p = 0.012), 2950 m (p = 0.02) and 3680 m groups (p = 0.005). The analysis revealed an interaction effects between the group and face direction, F (3, 102) = 4.90, p = 0.003, η2p = 0.13. Simple effect analysis showed the latency of N170 was significant later in all groups for inverted face compared to upright face (ps < 0.001). Further analysis revealed both upright and inverted faces in the 4530 m group significant later N170 components than 2950 m (p = 0.004, p = 0.037); the N170 of inverted faces in the 4530 m group significant later than 3680 m (p = 0.007).

Scalp potential topography

Figure 2 shows the scalp potential topography of P1 and N170 evoked by upright faces (left) and inverted faces (right) at different elevations. No significant difference in P1 amplitude was found between the two conditions from 80 to 150 ms at four elevations, but a significant difference was observed between the left and right brain regions, as confirmed in the brain topographic map. Topographic maps of P1 were made on the basis of peak values in the 80–150 ms time window, and the whole-brain distribution showed greater activation in the right temporal area than in the left temporal lobe in each region. A significant difference in the N170 amplitude of bilateral temporal lobes from 80 to 150 ms was found between the two conditions, as confirmed in brain topographic maps. The topographic map of N170 was drawn on the basis of the peak in the 150–200 ms time window, which is consistent with the significant main effect of face direction or brain area found by statistical analysis. In the whole-brain distribution, the activation degree of the inverted face was more significant than the upright face; the right temporal lobe was greater than the left temporal lobe.

sLORETA results

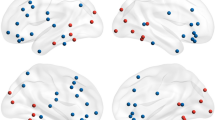

Images representing the electrical activity of each voxel in the neuroanatomical MNI space can be obtained using the sLORETA non-parametric mapping tool, where the colour scale bar represents the log-F-ratio of each voxel. The spatial characteristics of the face inversion effect at different altitudes were compared. The N170 waves evoked under inverted face conditions at 347, 2860, 3896 and 4530 m were measured. The results of the activated brain regions of N170 showed that compared with the plain group, the 2860 m group has a margin difference (p = 0.066) in the superior temporal gyrus and temporal lobe (BA 22 and 38, MNI coordinates: x = 55, y = 15, z = − 5; x = 45, y = 25, z = − 25, Fig. 3A). Non-significant voxel or cluster of suprathreshold voxels at the 3680 m group was located (Fig. 3B); the 4530 m group has a significant increase (p = 0.048) in the temporal lobe and superior temporal gyrus (BA 22 and 38, MNI coordinates: x = 55, y = 15, z = − 5; x = 45, y = 25, z = − 25, Fig. 3C).

The image source of N170 of the plain group and the plateau group under the condition of inverted face. There was a significant activation for 4530 m than 347 m (p = 0.048) in the temporal lobe and superior temporal gyrus (BA 22 and 38). (A: 347 vs. 2950; B: 347 vs. 3680; C: 347 vs. 4530.). The data presented in this figure represent the average results from all participants.

The spatial characteristics of the face inversion effect among the three plateau regions were also analysed. The results revealed a non-significant voxel or cluster of suprathreshold voxels between the 2950 and 3680 m groups (Fig. 4A). A non-significant voxel or cluster of suprathreshold voxels was located between the 2950 and 4530 m groups (Fig. 4B). Non-parametric analyses showed that the 3680 m group statistically differ from the 4530 m group with regard to significant voxel or clusters of supra-threshold voxels in the temporal lobe (BA 22, MNI coordinates: x = − 50, y = 10, z = − 5), superior temporal gyrus (BA 38, MNI coordinates: x = − 45, y = 15, z = − 20) and sub-gyral (BA 13, MNI coordinates: x = − 50, y = 10, z = 0, p = 0.007). The clusters of supra-thresholds were in left BA 38 and 22 (Fig. 4C).

The image source of N170 of between the plateau group under the condition of inverted face. There was a significant activated for 4530 m than 3680 m (p = 0.008) in the temporal lobe, superior temporal gyrus, and sub-gyral (BA 22, 38, and 13). (A: 2950 vs. 3680; B: 4530 vs. 3680; C: 3680 vs. 4530). The data presented in this figure represent the average results from all participants.

Discussion

The present study investigated the effects of altitude on the spatiotemporal dynamics of face recognition, with a focus on holistic processing indexed by the face inversion effect. By analyzing ERP components (P1 and N170) in individuals residing at four distinct altitudes (347 m, 2950 m, 3680 m, and 4530 m), our findings revealed significant altitude-dependent variations in both early and late stages of face processing. These results provide novel insights into how hypoxic environments modulate neural mechanisms underlying face recognition, particularly highlighting the vulnerability of holistic processing to high-altitude hypoxia.

Early visual processing (p1): right hemisphere dominance and altitude effects

The P1 component, reflecting early visual categorization, exhibited a robust right-hemispheric dominance across all altitudes, with inverted faces eliciting larger amplitudes than upright faces. This aligns with previous studies suggesting that the right hemisphere specializes in rapid global processing of facial configurations23,24. Notably, P1 latency was earlier in the 2950 m group compared to higher-altitude groups, suggesting that mild hypoxia may transiently enhance neural excitability, possibly through adaptive mechanisms such as increased cerebral blood flow. However, at 4530 m, delayed P1 latencies for inverted faces indicate that severe hypoxia disrupts early perceptual encoding, likely due to cumulative metabolic stress impairing neuronal efficiency25. These results underscore the nonlinear relationship between altitude and cognitive function, where moderate hypoxia may initially boost performance, but extreme hypoxia overwhelms compensatory mechanisms.

Holistic processing (n170): hypoxia-induced impairments

The N170, a hallmark of configural face processing, showed significant inversion effects (larger amplitudes and delayed latencies for inverted faces), consistent with its role in holistic integration26,27. Critically, the N170 latency for inverted faces was markedly delayed at 4530 m compared to lower altitudes, indicating impaired holistic processing under severe hypoxia. This finding resonates with studies linking oxygen deprivation to reduced synaptic plasticity in temporo-occipital regions, including the fusiform face area and occipital face area28. Furthermore, sLORETA source localization revealed heightened activation in the superior temporal gyrus (BA 22/38) at 4530 m, suggesting compensatory recruitment of adjacent regions to offset fusiform face area inefficiency. Such compensatory efforts, however, appear insufficient to fully restore holistic processing, as evidenced by prolonged N170 latencies. These results align with the neural efficiency hypothesis, which posits that hypoxia disrupts specialized neural networks, forcing the brain to engage less optimal pathways29.

The consistent right-hemispheric dominance for P1 and N170 components across altitudes reinforces the notion that the right hemisphere is central to holistic face processing30,31. However, the pronounced delays in N170 latencies at 4530 m suggest that this hemisphere is particularly susceptible to hypoxia. This may stem from the right hemisphere’s reliance on distributed neural networks for configural integration, which are more vulnerable to oxygen deficits than the left hemisphere’s feanalytical processing pathways. Our sLORETA findings further support this, showing that hypoxia-induced activation shifts occur predominantly in right-lateralized temporal regions. These findings have critical implications for populations exposed to high-altitude environments, such as mountaineers, pilots, and military personnel. Impaired holistic processing at extreme altitudes could hinder social interactions reliant on rapid face recognition, potentially compromising teamwork and decision-making.

9 was the first to investigate the face inversion effect through the learning recognition test, suggesting it is more difficult to recognise inverted faces than to recognise upright faces whilst recognizing objects such as houses or airplanes, which do not show an inversion effect. The face inversion effect was primarily due to the fact that people’s perception of the structure of the face or the whole face was inverted32,3326.used ERP technology to find the early specific component of face recognition—N170, showing that inverted faces evoked significantly later latencies and more positive amplitudes than upright faces7,34. The N170 component is not affected by facial expression, gender, race, familiarity or top-down control of attention and is automatically processed35. The face processing model proposed by36 points out that in the early stage of face processing (approximately 120 ms, P1), a rapid perception stage was jointly performed by the amygdala, subcortical tissue and striatum cortex, which is used to process significant stimuli. P1 was also considered as one of the earliest objective indicators of endogenous processing of visual stimulus types (e.g. faces vs. non-faces) and changes in the structure of spatial stimulus (e.g. face reversal), reflecting the crude and rapid early classification of faces by the amygdala, subcortical tissue and visual cortical detection system37.

Studies have indicated that at around 120 ms (P1), the organism is more sensitive to the low-level physical properties of stimuli and has completed the early classification38. Although the person can discriminate between face-like and non-face-like stimuli (expert and non-expert stimuli)39 it cannot classify stimuli in detail40. This study result indicated that the P1 evoked by inverted faces did not show later latency or positive amplitude compared with upright faces; the latency of inverted faces was significantly affected by altitude factors, with the earlier latency under mild hypoxic conditions (2950 m group) and significantly later latency after increased hypoxia (4530 m group). The results are consistent with those of Pagani et al., which may be due to the organism’s habituation through self-regulation in a mildly hypoxic environment for a long time41. The present study concluded that mild hypoxic stimulation at 2950 m altitude increased neural excitability. However, with the increase of altitude, the effect of hypoxia exceeded the threshold of body habituation, which led to the beginning of the cognitive decline, as evidenced by a significant increase in the latency of P1. This study also revealed a significant difference in the latency of P1 in a high-altitude (4530 m group). The mild hypoxic stimulation increases neural excitability. With further increases in altitude, the effects of hypoxia and other factors become more severe. Such effects exceed the body’s habituation threshold; cognitive ability begins to decline, and the latency of P1 begins to decline significantly. The aforementioned effects may be due to the following factors: As altitude increases, low oxygen gradually increases the task load, and when a certain altitude is reached, the identification of inverted faces with more serious task difficulty is more complex and time consuming. The differences between the upright and inverted faces are processed in different ways, and the differences can be significant under the effect of altitude. The mechanism by which information processing changes when the altitude rises to a certain height is the early perception of the organism that is sensitive to altitude factors.

In addition, the amplitude of P1 in the right brain region was more positive than in the left region, showing the advantage of the right brain processing intensity. This study showed that the face inversion effect was significant in different altitudinal environments and showed a dominance of processing intensity in the right brain region. The results are consistent with those of previous studies24. With the increase in altitude, the latency of N170 was initially earlier and then later, which was similar to that of P1. The higher the altitude, the lower the oxygen content in the air, which increases the body’s nerve excitation. The study results also revealed that the difference in the latency and amplitude of N170 evoked by upright and inverted faces tended to decrease during the gradual increase in altitude, indicating the weakening of the face inversion effect. Task difficulty primarily influences stimulus perception in plain areas and medium-to-high-altitude environments. By contrast, at higher altitudes, low oxygen gradually overwhelms the effect of perceived task difficulty and becomes the main factor affecting the body’s perception of stimuli. Task difficulty is the main factor in stimulus perception in plain and medium-to-high-altitude environments.

By contrast, in higher altitude areas, low oxygen gradually overwhelms the perceptual load on the body’s perception of task difficulty and becomes the main factor affecting the body’s perception of stimuli. Secondly, a threshold for the effect of face inversion at approximately 4000 m altitude is observed, which may be consistent with the findings of previous studies42. In addition, low oxygen may affect the overall conformational processing of upright faces differently than the local feature processing of inverted faces. The effect of low oxygen and other factors on overall conformational processing is more significant, whereas the specific processing effect is relatively mild.

The occurrence of cognitive ability does not decrease but increases in the altitude ranging from 3000 to 3700 m. This finding may be due to two factors: Firstly, this study employed a task design involving divided attention, where participants performed a simple cognitive task (counting sunflowers) while simultaneously being presented with face stimuli. Previous studies have generally concluded that hypoxia has a more negligible effect on simple cognitive tasks25; crucially, the early sensory/perceptual processing indexed by components like P1 and N170 is considered relatively automatic and less dependent on top-down attentional control compared to later cognitive stages. Secondly, P1 and N170 belong to the early components of EEG, which are primarily not affected by the top-down control of attention directed towards the faces and can exclude interference from higher-level mental cues. Therefore, the present study utilized a face inversion paradigm within this divided attention context, specifically targeting these early ERP components. This approach provides a basis for studying the effects of different altitudes on early perceptual stages of organismal cognition through more objective EEG indicators.

Limitation

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the exclusive inclusion of male participants limits generalizability to females, who may exhibit different hypoxia tolerance profiles. Second, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences about altitude effects; longitudinal studies tracking acclimatization dynamics are needed. Third, the use of static facial stimuli may not fully capture real-world face recognition, which often involves dynamic, expressive faces. Future research should incorporate diverse stimuli and multimodal neuroimaging (fMRI) to disentangle structural and functional adaptations to hypoxia.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that altitude exerts a profound influence on the neural correlates of face recognition, with holistic processing being particularly vulnerable to severe hypoxia. Mild hypoxia may transiently enhance early perceptual encoding, but extreme altitudes disrupt configural integration, necessitating compensatory neural recruitment. These findings advance our understanding of environmental impacts on cognition and underscore the need for adaptive strategies in high-altitude settings. Future work should explore individual differences in hypoxia tolerance and the efficacy of interventions to preserve cognitive function in low-oxygen environments.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Z.L.), upon reasonable request.

References

Sitko, S., Cirer-Sastre, R. & López Laval, I. Effects of high altitude mountaineering on body composition: a systematic review. Nutr. Hosp. 36 (5), 1189–1195 (2019).

Heinrich, E. C. et al. Cognitive function and mood at high altitude following acclimatization and use of supplemental oxygen and adaptive servoventilation sleep treatments. PLoS One 14 (6), e0217089. (2019).

Miguel, P. M. et al. Prefrontal cortex dopamine transporter gene network moderates the effect of perinatal hypoxic-ischemic conditions on cognitive flexibility and brain Gray matter density in children. Biol. Psychiatry. 86 (8), 621–630 (2019).

Bekker, A. et al. Physostigmine reverses cognitive dysfunction caused by moderate hypoxia in adult mice. Anesth. Analg. 105 (3), 739–743 (2007).

Davis, J. E. et al. Cognitive and psychomotor responses to high-altitude exposure in sea level and high-altitude residents of Ecuador. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 34 (1), 2 (2015).

Bublatzky, F., Pittig, A., Schupp, H. T. & Alpers, G. W. Face-to-face: perceived personal relevance amplifies face processing. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 12 (5), 811–822 (2017).

Gao, C., Conte, S., Richards, J. E., Xie, W. & Hanayik, T. The neural sources of N170: Understanding timing of activation in face-selective areas. Psychophysiology 56 (6), e13336. (2019).

Tanaka, H. Face-sensitive P1 and N170 components are related to the perception of two-dimensional and three-dimensional objects. Neuroreport 29 (7), 583–587 (2018).

Yin, R., LOOKING AT UPSIDE-DOWN & FACES. J. Exp. Psychol. 81 (1), 141–145. (1969).

Itz, M. L., Schweinberger, S. R. & Kaufmann, J. M. Familiar face priming: the role of Second-Order configuration and individual face recognition abilities. Perception 47 (2), 185–196 (2018).

Wang, H., Sun, P., Ip, C., Zhao, X. & Fu, S. Configural and featural face processing are differently modulated by attentional resources at early stages: an event-related potential study with rapid serial visual presentation. Brain Res. 1602, 75–84 (2015).

Caharel, S. et al. Other-race and inversion effects during the structural encoding stage of face processing in a race categorization task: an event-related brain potential study. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 79 (2), 266–271 (2011).

Civile, C., Obhi, S. S. & McLaren, I. P. L. The role of experience-based perceptual learning in the face inversion effect. Vis. Res. 157, 84–88 (2019).

Civile, C. et al. Testing the effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on the face inversion effect and the N170 event-related potentials (ERPs) component. Neuropsychologia 143, 107470 (2020).

Bliemsrieder, K. Cognition and neuropsychological changes at altitude. (2023).

Clarkson, J. J., Hirt, E. R., Jia, L. & Alexander, M. B. When perception is more than reality: the effects of perceived versus actual resource depletion on self-regulatory behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 98 (1), 29 (2010).

Su, R. et al. The effects of long-term high-altitude exposure on cognition: A meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 105682 (2024).

Zheng, Y. et al. Sluggishness of Early-Stage face processing (N170) is correlated with negative and general psychiatric symptoms in schizophrenia. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10, 615 (2016).

Gao, L. et al. Aging effects on early-stage face perception: an ERP study. Psychophysiology 46 (5), 970–983 (2009).

Pascual-Marqui, R. D. Standardized low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA): technical details.. Method Find Exp Clin 24(Suppl D), 5–12 (2002).

Jurcak, V., Tsuzuki, D. & Dan, I. 10/20, 10/10, and 10/5 systems revisited: their validity as relative head-surface-based positioning systems. Neuroimage 34 (4), 1600–1611 (2007).

Sekihara, K., Sahani, M. & Nagarajan, S. S. Localization bias and Spatial resolution of adaptive and non-adaptive Spatial filters for MEG source reconstruction. Neuroimage 25 (4), 1056–1067 (2005).

Itier, R. J. & Taylor, M. J. N170 or N1? Spatiotemporal differences between object and face processing using erps. Cereb. Cortex. 14 (2), 132–142 (2004).

Colombatto, C. & McCarthy, G. The effects of face inversion and face race on the P100 ERP. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 29 (4), 664–676 (2017).

McMorris, T., Hale, B. J., Barwood, M., Costello, J. & Corbett, J. Effect of acute hypoxia on cognition: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Neurosci. Biobehavioral Reviews. 74, 225–232 (2017).

Bentin, S., Allison, T., Puce, A., Perez, E. & McCarthy, G. Electrophysiological studies of face perception in humans. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 8 (6), 551–565 (1996).

Gao, Y. et al. Full waveform inversion beneath the central andes: insight into the dehydration of the Nazca slab and delamination of the back-arc lithosphere. J. Geophys. Research: Solid Earth. 126 (7). e2021JB021984 (2021).

MacLean, M. W. Neural correlates of conscious and unconscious visual processing in neurotypical and cortical visually impaired populations assessed with fMRI. (2023).

Chen, Y. & Zhang, J. How energy supports our brain to yield consciousness: insights from neuroimaging based on the neuroenergetics hypothesis. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 15, 648860 (2021).

Proverbio, A. M. Sexual dimorphism in hemispheric processing of faces in humans: A meta-analysis of 817 cases. Soc. Cognit. Affect. Neurosci. 16 (10), 1023–1035 (2021).

Reinke, P., Deneke, L. & Ocklenburg, S. Asymmetries in event-related potentials part 1: A systematic review of face processing studies. International J. Psychophysiology 112386. (2024).

Leder, H. & Bruce, V. When inverted faces are recognized: the role of configural information in face recognition. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. A. 53 (2), 513–536 (2000).

Maurer, D., Grand, R. L. & Mondloch, C. J. The many faces of configural processing. Trends Cogn. Sci. 6 (6), 255–260 (2002).

Tian, Y., Zhang, H., Pang, Y. & Lin, J. Classification for Single-Trial N170 during responding to facial picture with emotion. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 12, 68 (2018).

Eimer, M., Kiss, M. & Nicholas, S. Response profile of the face-sensitive N170 component: a rapid adaptation study. Cereb. Cortex. 20 (10), 2442–2452 (2010).

Adolphs, R. Neural systems for recognizing emotion. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 12 (2), 169–177 (2002).

Itier, R. J. & Taylor, M. J. Inversion and contrast Polarity reversal affect both encoding and recognition processes of unfamiliar faces: a repetition study using erps. Neuroimage 15 (2), 353–372 (2002).

Johannes, S., Münte, T. F., Heinze, H. J. & Mangun, G. R. Luminance and Spatial attention effects on early visual processing. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 2 (3), 189–205 (1995).

Gauthier, I., Skudlarski, P., Gore, J. C. & Anderson, A. W. Expertise for cars and birds recruits brain areas involved in face recognition. Nat. Neurosci. 3 (2), 191–197 (2000).

Nemrodov, D., Niemeier, M., Mok, J. N. Y. & Nestor, A. The time course of individual face recognition: A pattern analysis of ERP signals. Neuroimage 132, 469–476 (2016).

Pagani, M., Ravagnan, G. & Salmaso, D. Effect of acclimatisation to altitude on learning. Cortex 34 (2), 243–251 (1998).

Guo, F. et al. A longitudinal study on the impact of high-altitude hypoxia on perceptual processes. Psychophysiology 61 (6), e14548. (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G., Z.L., and X.F.; methodology, S.Z.; software, X.W.; resources, H.J., and Z.L.; data curation, S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; writing—review and editing Z.L, H.J., X.W., X.F., and S.C.; supervision, Z.L.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, S., Luo, Z., Jiang, H. et al. Effect of altitude on the spatiotemporal signal characteristics of inversion face recognition. Sci Rep 15, 25462 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10442-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10442-y