Abstract

One of the most significant occupational health issues in the textile industry is WMSDs. Nonetheless, there are significant data gaps in the field concerning workers in the textile industry, particularly in developing nations like Ethiopia. Closing this gap was the aim of this study. A cross-sectional study was conducted from March to April 2023 to determine the prevalence of WMSDs and related factors among Kombolcha textile industry workers. The data were gathered through the use of physical measurements and pretested, standardized Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaires. EPI Info version 7 and Stata version 14.0 were used for data entry and analysis, respectively. Potential risk factors for WMSDs were identified through the use of bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR), with 95% confidence intervals and a P < 0.05 were used to assess the level of significance. Out of the 385 individuals, 163 (42.3%) were females, with a mean age of 29 ± 7.37 years. 237 (61.56%) of the 385 participants (95%CI: 56–66) had WMSDs in the past 12 months. The most common types of WMSDs were neck (31.4%), shoulder (25.7%), elbow (14.2%), hand/wrist (11.4%) and upper back (29.6%). Age (AOR: 4, 95% CI: 15–10.4), job satisfaction (AOR: 1.5, 95% Cl: 2.25–4.4), work shift (AOR: 2, 95% CI: 1.18–3.6), and work experience (AOR: 2.18, 95% CI: 1.35–3.5) were all strongly correlated with WMSDs. Strategies to improve training for preventing WMSDs and alter the contributing factors should be impacted by these findings. We encourage the public, businesses, and national governments to fully address WMSDs in order to lower worker mortality and increase productivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) are groups of syndromes characterized by symptoms of soft tissue pain, swelling, stiffness, weakness, discomfort, painfulness, tingling, numbness and loss of function that can be caused or aggravated by work-related exposures and the circumstances of its performance1. WMSDs are the most significant public health issues in the workplace worldwide, impacting not only the health of employees but also the health system and resulting in financial and social expenses2,3 and a poor quality of life4,5 workplace injury and disability6,7. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that between 50 and 70% of workers develop WMSDs, that 317 million people suffer from WMSDs each year, and that 6,300 people die from WMSDs every day8.

A recent statistics report by the Health and Safety Executive of Great Britain 2015, showed that WMSDs accounted for 44% of the prevalence of all work related ill-health and the number of new cases of WMSDs was 169,000, an incidence rate of 530 cases per 100,000 people. An estimated 9.5 million working days were lost due to WMSDs9. Furthermore, WMSDs result in losses of about $215 billion in the United States, $26 billion in Canada, and 38 billion euros in Germany10. Consequently, it has been identified as one of the primary causes of economic burdens, lost productivity, and human suffering11.

In developing countries, the disease burden of WMSDs is ranked as one of the three most common causes of disability and non-communicable disease overburden12,13. According to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis study conducted in India, between 47% and 92% of workers in manufacturing industries have WMSDs14. In many African countries, WMSDs are a problem with the prevalence of any musculoskeletal disease ranging from 15 to 93.6%15. For instance, in South Africa, the incidence of work-related back pain, neck pain, and carpal tunnel syndrome is between 15% and 60%, indicating that a high proportion of the working population is at risk of developing one or more WMSDs16.

WMSDs are one of the most important occupational health problems in the garment industry. This disorder causes long periods of work disability and reduces productivity17,18. It can significantly affect the quality of life and result in losing work time or working absenteeism, increasing work restrictions, changing to another job, with considerable compensation and losses on the individual, the organization, the family and societal levels19,20,21. Many individual workers appear to have suffered serious economic consequences of WMSDs, including losing homes, incurring large out-of-pocket expenses, being divorced, loss of health insurance, and facing economic insecurity due to financial hardship and also a negative social impact on the individual22,23.

Like other African countries, Ethiopia is facing health problems related to occupation and at the same time getting the emerging challenges from industrialization and rapid urbanization. There are particularly serious data limitations in the area of WMSDs, especially in developing countries like Ethiopia, due to factors including long latency of many diseases before the symptoms are detected and the weakness in the national capacity for identification, diagnosis and compensation of occupational diseases24.

Considering the high expansion of textile industries in Ethiopia, it is important to monitor the health risk associated with occupational exposure25. Recently, Ethiopia has reinforced its policy towards rapid industrialization for its economic development, but occupational healthcare facilities and activities are not well organized in the country and there is a poor working environment and no strong functioning health and safety system. Nowadays, the ministry of labor and social affairs (MOLSA) working on the implementation of occupational health and safety in many industries, but the practice is still not well organized26. Despite this, data on WMSDs among textile industry workers in Ethiopia is limited. Therefore, this study was planned to determine the magnitudes of WMSDs and associated factors among workers in the Kombolcha textile industry.

Materials and methods

Study area

A cross-sectional study was conducted among workers in Kombolcha textile factory. Kombolcha textile factory was established in 1986 in South Wollo Zone, Kombolcha town in Amhara Regional State and located 380 km away from Addis Ababa. The factory has a total of 1452 workers (779 males and 673 females) among this 998 workers are involved in production processes. Workers from spinning were (312), weaving (315), processing and finishing (277), engineering (94), and administration and others (454). It is one of the largest private limited companies in the town which is engaged in the production of towels, bed sheets, and home fabrics using cotton.

Study design and period

An institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted from March to April 2023.

Source and study populations

The source populations were all employees of the Kombolcha textile industry, while the study populations were the randomly chosen employees of the Kombolcha textile industry.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Workers who had been employed in the textile industry for a year or more and who had no prior history of WMSDs were included in the study; workers who had previously been involved in a car accident or other work-related incident, who were physically deformed, or who were pregnant were excluded.

Sample size determination

The sample size for the first and the second objectives was calculated by considering the following assumptions.

For the first objective

The sample size was calculated using a single proportion formula by taking a proportion of P = 65.4% %27, confidence interval 95% and margin of error 5%

By adding a 10% non-response rate, the final sample size of the study was 385.

For objective 2 (Associated factors to WMSDs)

For the second objective, the sample size was calculated by taking associated risk factors from previous studies related to WMSDs by considering Power (Zβ) 80%, ratio (unexposed : exposed) and confidence interval of 95%.

Therefore, as different literatures showed that age28, awkward posture29, alcohol drinking30 and year of service8 are risk factors for WMSDs. Therefore: The sample size calculated by using Epi Info 7 is as follows (Table 1):

The maximum sample size for factors is 208; therefore, for the sake of representativeness, a large sample size was used for final data collection, as 385 is the maximum number.

Sampling procedures

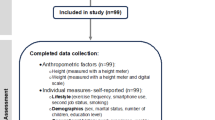

The study participants were distributed proportionately among the departments using the stratified sampling technique. Each working department’s study participants were chosen using a computer-generated simple random sampling technique (Fig. 1).

Operational definitions

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders

workers who had experienced pain, ache, or discomfort in any part of their bodies for at least 2 to 3 work days in the previous week or previous 12 months were considered31.

Body mass index (BMI)

Weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters (kg/m2). Based on the calculation, BMI is classified as follows: Underweight = BMI < 18.5, Normal range = BMI 18.5–24.9, Overweight = BMI b/n 25.00-29.9 and, Obese = BMI ≥ 3032.

Job satisfaction

A score measured using the generic job satisfaction scale answered as yes (32 upto50) and answered no (10-31) (33).32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50 and no10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33

Job stress

A score measured using the workplace stress scale as yes (16-40) 16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39 and no(≤ 15)9.

Cigarette smoking

It is the practice of smoking cigarettes by textile workers for at least one stick of cigarette per day34.

Physical exercise

Performing any kind of physical exercise at least two times per week for 30 min34.

Data collection tools and procedures

A standardized measurement scale and a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire derived from multiple prior investigations were employed. There were four sections to the questionnaire. Data on socio-demographics, including sex, age, marital status, educational level, work experience and monthly income, were intended to be gathered in the first section. The evaluation of WMSDs is the subject of the second portion of the questionnaire. Standardised Nordic musculoskeletal questionnaires, which were created as part of a project supported by the Nordic Council of Ministers, were used to collect data on the prevalence of WMSDs35 through face-to-face interviews and the responses to any of the questions are either “Yes” or “No”. The questionnaires’ validity and reliability were examined, and each section’s results were satisfactory. The NMQ were used to collect neck, shoulder, upper back, lower back, hip /thigh, knee/leg, elbow, ankle/foot and wrist /hand musculoskeletal symptoms. It evaluates the prevalence of symptoms in the last 12 months. Physical measurement was also done to measure the participants’ height and weight for body mass index calculation. The participants’ height and weight were measured using calibrated equipment.

The questionnaire’s third section contains information used to assess behavioural and psychosocial factors such as alcohol consumption (yes/no), cigarette smoking (yes/no), recreation time, BMI (kg/m2), past MSD history (yes/no), job stress (yes/no), job satisfaction (yes/no) and physical exercise (yes/no). The final section of the questionnaire incorporated information on the working environment and ergonomic-related factors such as employment status, work shift, overtime, working department, work posture, safety training, highly repetitive work, availability of light, and high-loaded work.

Data quality assurance

The data was collected using a well-prepared data collection tool, and the English version of the questionnaire was translated into Amharic and back to English to ensure consistency. Cronbach’s alpha was used to test the reliability of the translated questionnaire, which was found to be 0.76. Both supervisors and data collectors received two days of training on the guidelines and procedures for data collection, and closer supervision was practiced throughout the process. A pre-test of 5% of the questionnaires was conducted among textile workers in Kombolcha industrial park prior to the actual data collection process. Several terms and misinterpretations were changed, and the unclear questions were corrected in light of the pretest analysis result. The completed questionnaires were examined by the principal investigator and supervisors to make sure the data was accurate and consistent, and the data collectors received the required feedback the following morning.

Data management and statistical analysis

After being verified for accuracy and consistency, the data was imported into Epi Info version 7 for coding, cleaning, editing, and organizing, and it was exported into Stata version 14.0 for additional analysis. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, while the mean and standard deviation were calculated for continuous variables. The information was presented using tables and graphs after descriptive statistics were calculated. The present study employed tables to display correlations and data distributions, and graphs to illustrate comparisons between the prevalence of WMSDs distribution in various body areas. Missing data were addressed during the analysis by using estimated mean values.

Prior to doing binary logistic regression analysis, the variables’ multicollinearity, outliers, and normality were examined. A variance inflation factor was used to check for multicollinearity and all variables had values less than five. The study employed bivariate analysis, and to address the impact of confounding variables and for more comprehensive models, variables with a P value of less than 0.2 were transferred and subjected to multivariable logistic regression analysis. The presence of an association between the outcome variable and independent variables was determined using the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of p-value < 0.05. Using the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, the model’s fit was examined, and the model was well-fitting, with a p-value of 0.87.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 385 employees responded to the survey, achieving a 100% response rate. Males made up over half of the group, with 222(57.7%) of the participants having a mean age of 27. Out of the employees, 27(7%) had only completed primary school, and 129(33.5%) were single. 64(16.6%) had a monthly income of more than 6000 ETB, and 225(58.4%) had more than five years of work experience (Table 2).

Prevalence of WMSDs

In this study, 237 (61.56%) of the 385 industry workers (95%CI: 56–66) had WMSDs during the previous 12 months. The body parts most affected were the neck (31.4%), shoulder (25.7%), elbow (14.2%), hand/wrist (11.4%) and upper back (29.6%) (Fig. 2).

Behavioral and psychosocial factors of WMSDs

Of the employees, 22(5.7%) reported smoking cigarettes, and one-third (33%) reported drinking alcohol. Furthermore, 48(12.5%) employees reported having leisure time. Additionally, 241(62.6%) employees are classified as overweight based on their BMI index, and only 42(10.9%) employees have a history of WMSDs (Table 3).

Work-related factors of WMSDs

More than two-thirds, or 265(68.8%), of them work in shifts, and 323(83.9%) of them have permanent employment status. Furthermore, only forty-two (10.9%) employees worked overtime. Additionally, weaving, spinning, engineering, and processing & finishing departments employ 84(21.8%), 83(21.6%), 25(6.5%), and 73(18.9%) workers, respectively (Table 4).

Factors associated with WMSDs

WMSDs were crudely associated with age, sex, educational status, marital status, work experience, monthly income, work shift, work posture, job satisfaction, physical exercise, alcohol use, history of MSDs, and heavy workload. The results of the adjusted logistic regression analysis showed that WMSDs was significantly correlated with age (AOR: 4, 95% CI: 1.5–10.4), job satisfaction (AOR: 1.5, 95% Cl: 2.25–4.4), work shift (AOR: 2, 95% CI: 1.18–3.6), and work experience (AOR: 2.18, 95% CI: 1.35–3.5) (Table 5).

Discussion

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) reports that WMSDs are the second most frequent cause of occupational disability and injury, after occupational respiratory diseases36,37. Aside from having an effect on a people’s health and welfare, the issue is more serious for factory workers, who have an impact on a country’s economy by reducing worker productivity17,18. Thus, the goal of the current study was to evaluate WMSDs and associated factors among workers in the Kombolcha textile industry. The present study found that WMSDs were present in 61.56% of the workers in the Kombolcha textile industry. The most common types of WMSDs were neck (31.4%), shoulder (25.7%), elbow (14.2%), hand/wrist (11.4%) and upper back (29.6%). The factors that demonstrated a significant correlation with WMSDs were age, work experience, work shift, and job satisfaction.

The study’s results indicated that 61.56% (95% CI: 56–66) of textile industry workers had WMSDs. It was consistent with the former’s researche in India (58%)38 and, Turkey (59%)39. However, the finding was lower than the studies in Gondar, Ethiopia (81.5%)40, Nigeria (71.6%)41,Taiwan (84%,)42 and Bangladesh (78%)43; in contrast, the observed WMSDs in this study were higher than similar previous studies in Hawassa, Ethiopia (47.7%)44, Mekele, Ethiopia (55%)45, and India (37%)46. The disparity may result from differences in study participants, work load and working environments. In order to reduce the problem, healthcare providers must provide the owners and factory workers with extensive training and close supervision.

The study found that the most common musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) were found in the neck (31.4%), shoulder (25.7%), elbow (14.2%), hand/wrist (11.4%) and upper back (29.6%). The prevalence rate for neck MSDs was similar to an Ethiopian study40. In addition, the rates of upper back MSDs were noted in comparison to findings from Ethiopia47. The elbow prevalence rate was significantly lower than the 53.8% reported in a study conducted among Gondar restaurant employees40. Variations in study setting, workplace health practices, and assessment instruments may be the cause of these disparities.

Employee age was the variable in the current study that significantly correlated with WMSDs. One possible explanation is that older workers are more likely to receive specialized training and, as a result of their experience, are able to comprehend various forms of WMSDs prevention. Many earlier studies in Ethiopia38 Bangladesh43, South India48, and South Korea49 supported the conclusion. In order to improve their knowledge and prevent WMSDs, healthcare providers and other pertinent organizations should prioritize training younger employees.

Additionally, this study found that factory workers’ WMSDs can increase by more than two times (AOR = 2.18) if they have less work experience. This indicates that WMSDs were 2.18 times higher for employees with less work experience than for counterparts. One explanation for this could be that highly experienced employees are more likely to attend trainings that decrease problems and improve their problem-management skills. These findings are comparable to those of previous studies conducted in Ethiopia50,51. Therefore, in order to lower their level of WMSDs, it is imperative to offer training targeted at employees with less work experience.

Another significant factor that was found to contribute to the development of WMSDs was work shift. According to the current findings, participants who worked in shifts had a lower chance of developing WMSDs than their counterparts. This is because employees who work in a shift are more likely to reduce their exposure time, which is a preventative measure to lower risk. The results align with previous researches conducted in comparable environments52,53,54. Therefore, the factory’s owners must shift employees in order to reduce the negative effects on them and increase their productivity.

Employees with low job satisfaction were more likely to have higher WMSDs than their counterparts. This conclusion is further supported by research from Gonder, Ethiopia38, Gamo zone, Ethiopia55, Mekele, Ethiopia45, China56, and Greece57, which found that employees who were unsatisfied with their jobs were more likely to have WMSDs. This implied that increased job satisfaction might help employees protect themselves from WMSDs. A high level of job satisfaction is essential to protect workers from WMSDs. This necessitates the implementation of strict job satisfaction enhancement procedures by the factory owners. In order to safeguard employees against WMSDs and other financial hazards, like a decline in productivity, concerned organizations must carefully monitor WMSDs.

In general, the prevalence of WMSDs among the textile industry workers is prevalent in the current study and needs a lot of attention. In order to improve the situation and achieve the best outcomes, it is essential to concentrate on the influencing factors when solving the problem. Healthcare providers are required to provide rigorous health education and rigorous monitoring as the foundation for the activities implemented to prevent the issue. Therefore, considering the growth of Ethiopia’s industries and the seriousness of the health and productivity issues, everyone involved should pay close attention to this issue.

This study is subject to certain limitations. The use of self-reported data in this study raises the possibility that participants may give socially acceptable responses, which is the first research limitation. Comparing the study’s results with those of other target groups and research areas is another study limitation. This study may also have limitations due to its failure to specify symptom severity or frequency scales employed in modified versions of the NMQ. Notwithstanding these drawbacks, the study concentrates on important topics that are mostly pertinent to preventing WMSDs and increasing productivity.

Conclusion

This study evaluated WMSDs and associated factors among workers in the Kombolcha textile industry. This study found a high overall prevalence of WMSDs in over half of the workers in the Kombolcha textile industry. Significant factors associated with WMSDs include age, work experience, work shift and job satisfaction. The results of this study demonstrate how urgently policymakers must address WMSDs among workers in industrial settings by developing and enforcing regulations that encourage preventive measures. These findings should have an impact on strategies aimed at enhancing training for preventing WMSDs to change the factors that contribute to the issue. Thus, the challenge should be addressed by the Occupational Health and Safety departments of Wollo University through rigorous training. Furthermore, the factory should rigorously implement work shifts and improve workers’ job satisfaction focusing on employees with greater age and work experience. Thus, to reduce worker mortality and boost productivity, we urge factory owners, national governments, businesses, and industry workers should collaborate to fully address WMSDs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding auhor on reasonable request .

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- COR:

-

Crude Odd Ratio

- MSDs:

-

Musculo-skeletal Disorders

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- WMSDs:

-

Work-related Musculo-skeletal Disorders

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Sirajudeen, M. S., Alaidarous, M., Waly, M. & Alqahtani, M. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among faculty members of college of applied medical sciences, Majmaah university, Saudi arabia: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Health Sci. 12 (4), 18 (2018).

Abledu, J. & Abledu, G. Multiple logistic regression analysis of predictors of musculoskeletal disorders and disability among bank workers in Kumasi. Ghana. J. Ergon. 2 (111), 2 (2012).

Bevan, S.J.B.P. Economic impact of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) on work in Europe. Rheumatol. RC. 29 (3), 356–373 (2015).

Gebretsadik, A., Melaku, N. & Haji, Y. Community acceptance and utilization of maternal and community-based neonatal care services provided by health extension workers in rural Sidama zone: barriers and enablers: a qualitative study. Pediatr. Health Med. Ther. 11, 203 (2020).

Jahrami, H. et al. The examination of sleep quality for frontline healthcare workers during the outbreak of COVID-19. Sleep. Breath. 25 (1), 503–511 (2021).

Ansari, S., Varmazyar, S. & Bakhtiari, T. Evaluating the role of risk factors on the prevalence and consequence of musculoskeletal disorders in female hairdressers in qazvin: a structural equation modeling approach. J. Health. 9 (3), 322–332 (2018).

Kebede Deyyas, W. & Tafese, A. Environmental and organizational factors associated with elbow/forearm and hand/wrist disorder among sewing machine operators of garment industry in Ethiopia. Journal of environmental and public health. ;2014. (2014).

Tafese, A., Nega, A., Kifle, M. & Kebede, W. Predictors of occupational exposure to neck and shoulder musculoskeletal disorders among sewing machine operators of garment industries in Ethiopia. Sci. J. Public. Health. 2 (6), 577–583 (2014).

HSE. Summary report work-related musculoskeletal disorders, a tri‐sector exploration. (2018).

Da Costa, B. R. & Vieira, E. R. Risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review of recent longitudinal studies. Am. J. Ind. Med. 53 (3), 285–323 (2010).

Aweto, H. A., Tella, B. A. & Johnson, O. Y. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among hairdressers. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health. 28 (3), 545 (2015).

Hoy, D. G. et al. The global burden of musculoskeletal conditions for 2010: an overview of methods. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73 (6), 982–989 (2014).

Hoy, D. G. et al. Reflecting on the global burden of musculoskeletal conditions: lessons learnt from the global burden of disease 2010 study and the next steps forward. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74 (1), 4–7 (2015).

Mishra, S. et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among various occupational workers in india: a systematic review and meta-analysis. :uiae077. (2024).

Wanyonyi, N. & Frantz, J. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in africa: a systematic review. Physiotherapy 101, e1604–e5 (2015).

Collins, R. M., Van Janse, D. C. & Patricios, J. S. Common work-related musculoskeletal strains and injuries: CPD Article. South. Afr. Family Pract. 53 (3), 240–246 (2011).

Punnett, L. et al. Estimating the global burden of low back pain attributable to combined occupational exposures. Am. J. Ind. Med. 48 (6), 459–469 (2005).

Ergonomics, O. et al. Principles of Work Design. CRC; (2003).

Mirmohammadi, S. & Yazdani-Charati, J. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders and associated risk factors among nurses in a public hospital. Iran. J. Health Sci. 2 (3), 55–61 (2014).

Hämmig, O., Knecht, M., Läubli, T. & Bauer, G. F. Work-life conflict and musculoskeletal disorders: a cross-sectional study of an unexplored association. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 12 (1), 1–12 (2011).

Szucs, T. et al. Economic and social impact of epidemic and pandemic influenza. ;24(44–46):6776–6778. (2006).

Bhattacharya AJIJoIE. Costs of occupational musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) in the united States. ;44(3):448–454. (2014).

Morse, T. F. et al. The economic and social consequences of work-related musculoskeletal disorders: the Connecticut Upper-Extremity Surveillance Project (CUSP). ;4(4):209 – 16. (1998).

Safe, C. Healthy Workplaces for All. ILO. (2014).

Bhattacharya, A. Costs of occupational musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) in the united States. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 44 (3), 448–454 (2014).

Wheeler, J. & Goddard, K. Assessement of Ethiopia’s Labor Inspection System. (2013).

Girma, Z. Assessing the prevalence of work related musculoskeletal disorders and associated factors among workers in selected garments in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa university thesis report. ;2016. (2016).

Tegenu, H., Gebrehiwot, M., Azanaw, J. & Akalu, T. Y. Self-reported work-related musculoskeletal disorders and associated factors among restaurant workers in Gondar city, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. ;2021. (2021).

Etana, G., Ayele, M., Abdissa, D. & Gerbi, A. Prevalence of work related musculoskeletal disorders and associated factors among bank staff in Jimma city, Southwest ethiopia, 2019: an institution-based cross-sectional study. J. Pain Res. 14, 2071 (2021).

Mekonnen, T. H. The magnitude and factors associated with work-related back and lower extremity musculoskeletal disorders among barbers in Gondar town, Northwest ethiopia, 2017: A cross-sectional study. Plos One. 14 (7), e0220035 (2019).

Dagne, D., Abebe, S. M. & Getachew, A. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders and associated factors among bank workers in addis ababa, ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 25 (1), 1–8 (2020).

Yitayeh, A., Mekonnen, S., Fasika, S. & Gizachew, M. Annual prevalence of self-reported work related musculoskeletal disorders and associated factors among nurses working at Gondar Town Governmental Health Institutions, Northwest Ethiopia. (2015).

Mulugeta, H., Tamene, A., Ashenafi, T., Thygerson, S. M. & Baxter, N. D. Workplace stress and associated factors among vehicle repair workers in Hawassa city, Southern Ethiopia. PloS One. 16 (4), e0249640 (2021).

Gebremichael, G. & Kumie, A. The prevalence and associated factors of occupational injury among workers in Arba minch textile factory, Southern ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Occup. Med. Health Affairs. 3 (6), e1000222–e (2015).

Kuorinka, I. et al. Standard nordic questionnaries for the analysis of mussculoskeletal symptoms. IApplied Ergon. 8 (3), 233–237 (1987).

Storheim, K. & Zwart, J-A. Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Global Burden of Disease Studyp. 949–950 (BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, 2014).

Bernal, D. et al. Work-related psychosocial risk factors and musculoskeletal disorders in hospital nurses and nursing aides: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 52 (2), 635–648 (2015).

Shukriah, A., Baba, M., Jaharah, A. J. J. F. & Sciences, A. Prevalence and factors contributing to musculoskeletal disorder among garage worker in Malaysia. ;9(5S):1070–1079. (2017).

Ilban MOJJofbr. Musculoskeletal disorders among first class restaurant workers in Turkey. ;16(1):95–100. (2013).

Tegenu, H., Gebrehiwot, M., Azanaw, J. & Akalu, T. Self-Reported Work‐Related Musculoskeletal Disorders and Associated Factors among Restaurant Workers in Gondar City, Northwest Ethiopia, 2021;2021(1):6082506. (2020).

Maduagwu, S. M. et al. Occup. Med. Health Aff. ;20(29):132. (2014).

Chyuan, J-Y-A., Du, C-L., Yeh, W-Y. & Li, C-Y-J-O-M. Musculoskelet. Disorders Hotel Restaurant Workers ;54(1):55–57. (2004).

Yesmin, K. Prevalence of Common Work Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among the Restaurant Workers: Department of Physiotherapy (Bangladesh Health Professions Institute, CRP, 2013).

Tamene, A., Mulugeta, H., Ashenafi, T., Thygerson, S. M. J. J. E. & Health, P. Musculoskeletal disorders and associated factors among vehicle repair workers in Hawassa City. South. Ethiopia. 2020 (1), 9472357 (2020).

Melese, H., Gebreyesus, T., Alamer, A. & Berhe, A. J. J. P. R. Prevalence and associated factors of musculoskeletal disorders among cleaners working at Mekelle University, Ethiopia. :2239-46. (2020).

Sulaiman, S. K., Kamalanathan, P., Ibrahim, A. A. & Nuhu, J. M. J. I. J. R. M. S. Musculoskeletal disorders and associated disabilities among bank workers. ;3(5):1153–1158. (2015).

Tesfaye, A. H., Kabito, G. G., Aragaw, F. M. & Mekonnen, T. H. J. P. Prevalence and risk factors of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among shopkeepers in ethiopia: evidence from a workplace cross-sectional study. ;19(3):e0300934. (2024).

Subramaniam, S. & Murugesan SJIJoOS Ergonomics. Investigation of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among male kitchen workers in South India. ;21(4):524–531. (2015).

Lee, J. W., Lee, J. J., Mun, H. J. & Lee, K-J. Kim jjjaoo, medicine e. The relationship between musculoskeletal symptoms and work-related risk factors in hotel workers. ;25:1–10. (2013).

Kasaw Kibret, A., Fisseha Gebremeskel, B., Embaye Gezae, K. & Solomon Tsegay, G. J. P. R. Management. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders and Associated Factors Among Bankers in Ethiopia, 2020;2020(1):8735169. (2018).

Etana, G., Ayele, M., Abdissa, D. & Gerbi, A. J. J. P. R. Prevalence of work related musculoskeletal disorders and associated factors among bank staff in Jimma city, Southwest ethiopia, 2019: an institution-based cross-sectional study. :2071–2082. (2021).

Yizengaw, M. A., Mustofa, S. Y., Ashagrie, H. E. & Zeleke TGJAoM Surgery. Prevalence and factors associated with work-related musculoskeletal disorder among health care providers working in the operation room. ;72:102989. (2021).

Shafiezadeh, K. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among paramedics working in a large hospital in Ahwaz, southwestern Iran in 2010. (2011).

Yasobant, S. Rajkumar pjijoo, medicine e. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among health care professionals: A cross-sectional assessment of risk factors in a tertiary hospital. India 18 (2), 75–81 (2014).

Haftu, D., Kerebih, H. & Terfe, A. J. P. O. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders and its associated factors among traditional cloth weavers in Chencha district, Gamo zone, ethiopia, an ergonomic study. ;18(11):e0293542. (2023).

Xu, Y-W., Cheng, A. S. & Li-Tsang, C. W. J. W. Prevalence and risk factors of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in the catering industry: a systematic review\m {1}. ;44(2):107–116. (2013).

Tsigonia, A., Tanagra, D., Linos, A. & Merekoulias, G. Alexopoulos ecjijoer, health p. Musculoskelet. Disorders among Cosmetologists. 6 (12), 2967–2979 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Wollo University for funding this study and to the College of Medicine and Health Sciences’ Ethical Review Committee for granting ethical clearance. The supervisors, study participants, and all data collectors are also greatly appreciated by the authors.

Funding

Wollo University provided funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T.Y. was responsible for generating the concept of this research paper, analysed and interpreted data, wrote the main manuscript text, prepared figures and reviewed the manuscript. B.K. analysed and interprete data, wrote the main manuscript text and reviewed the manuscript. A.A.B. and A.E.B analysed and interprete data, present the result draft and reviewed the manuscript. T.N. analysed and interprete data, present the result draft, wrote the main manuscript text, prepared figures and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The ethical approval letter was issued by the Institutional Ethical Review Committee of Wollo University’s College of Medicine and Health Sciences with reference number CMHS/655/20/16. The factory and other relevant organizations in the research area received a letter of support. The research was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical guidelines. Prior to data collection, all participants were assured that their information would only be used for scientific research and were made aware of the study’s purpose. Prior to any data collection, each employee gave written informed consent. Participants were informed that their involvement would be completely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time for any reason. Additionally, they were free to ask any questions they had regarding the study. By avoiding potential identifiers, such as study participants’ names, and using only identification numbers as a guide, confidentiality was preserved. During the data collection period, respondents who reported experiencing severe musculoskeletal disorders were encouraged to seek medical assistance.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yirdaw, A.T., Kinfe, B., Belay, A.A. et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders and associated factors among workers in Kombolcha Textile Industry, Northeast Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 26260 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10775-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10775-8