Abstract

In this study, ZrO2 nanoparticles were synthesized by the hydrothermal method using different precursors and mineralizers. X-ray diffraction revealed that the choice of synthesis components has a significant impact on the phase composition and crystallinity of the resulting ZrO2 nanoparticles. Raman spectroscopy indicated that varying the combinations of precursors and mineralizers enables the formation of both cubic and tetragonal phases of ZrO2 within the samples. Transmission electron microscopy showed that the particle size ranges from 4 to 14 nm, with crystalline samples predominantly containing particles in the 5–6 nm range. In amorphous samples, nuclei with sizes between 5 and 10 nm were observed. TGA analysis demonstrated that all samples contain a substantial amount of synthesis by-products, reaching up to 30% of the total mass. Spectroscopic analysis of the optical properties determined that samples with more than 9% by-product content exhibit the highest absorption in the UV subrange. The phase stability of ZrO2 nanoparticles and the effect of temperature on the crystallization of amorphous samples were estimated using high-temperature X-ray diffraction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Zirconium dioxide (ZrO2) nanoparticles are a highly versatile material with significant potential for applications in optoelectronics1, energy storage devices2, dentistry3, catalysts4, water splitting reactions5, and as a precursor for the synthesis of ZrO2 – based ceramics. ZrO2 nanoparticles are considered highly promising due to their superior catalytic activity, outstanding optical properties (including high refractive index and low light absorption), high dielectric constant, excellent ionic conductivity, low thermal conductivity, exceptional hardness and flexural strength, as well as their chemical inertness at elevated temperatures, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility6,7,8,9.

ZrO2 exhibits polymorphism and possesses different crystal structures depending on the temperature. In the temperature range from room temperature to 1170 0C, ZrO2 has a monoclinic crystal structure (m – ZrO2)10. With increasing temperature, a martensitic transformation from the monoclinic to the tetragonal phase occurs (t – ZrO2), followed by a transition to the cubic phase (c – ZrO2) at approximately 2370 °C11. The superior mechanical, dielectric, optical and catalytic properties of ZrO2 are attributed precisely to the unstable at room temperature tetragonal and cubic ZrO2 phases6. Several approaches have been developed to stabilize the high-temperature phases of ZrO2. The most common strategy involves the incorporation of other metal oxides such as CeO2, MgO, Y2O3, or CaO12,13,14. In this approach, ions with atomic radii different from that of Zr are incorporated into the ZrO2 crystal lattice, effectively stabilizing the high-temperature phases by hindering shear displacement of ions during cooling. A different solution is to obtain ZrO2 nanoparticles smaller than 10–20 nm, which have metastable high-temperature phases at room temperature due to the Gibbs-Thomson effect15,16.

At present, ZrO2 nanoparticles are produced using various techniques, including chemical vapor deposition (CVD)17, electrospinning18, precipitation19, green synthesis20, thermolysis of novel precursors21, sol-gel22, and hydrothermal methods23. Hydrothermal synthesis stands out as a particularly promising method among the numerous available approaches. The ability to modify synthesis parameters such as temperature, duration, precursors, pH of the medium, and type of mineralizer creates an opportunity to vary the phase composition, size and morphology of ZrO2 nanoparticles. Thus, changing the precursor (e.g., using Zr(OH)4, ZrOCl2·8H2O, or ZrO(NO3)2·2H2O, etc.) affects the size and morphology of the synthesized particles. Nanorods with diameters below 100 nm and lengths of several micrometers were synthesized using a hydrothermal method without the addition of mineralizers24. According to the results reported by Liu Lu et al., variations in the precursor led to changes in particle size and phase composition, primarily due to the effects of the anion type and corresponding pH differences25. Additionally, adjustment of the pH of the medium, even when using the same starting material, results in significant changes in the phase composition and crystallinity of the synthesized samples. Mohsen et al. synthesized ZrO2 nanoparticles with varying monoclinic-to-tetragonal phase ratios and particle sizes ranging from 10 to 100 nm, by changing the pH of the medium from 2.6 to 14 using ZrOCl2·8H2O as a precursor26. It was previously reported that varying the synthesis temperature and pressure, precursor concentration, and pH of the medium during supercritical hydrothermal synthesis enables control over phase composition and particle size across a wide range27. ZrO2-based catalysts with TiO2, CeO2, and La2O3 additives were successfully produced via hydrothermal methods, achieving favorable adsorption/desorption properties6. The introduction of various mineralizers affects the degree of solubility of precursors, as well as the rate and quality of crystallization28. It was also shown that the use of different mineralizers leads to changes in the phase composition and size of ZrO2 nanoparticles29. Variation in synthesis temperature and duration affects the phase composition as a result of differences in the degree of crystallization and nanoparticle coarsening30.

When hydrothermal synthesis is used to produce ZrO2 nanoparticles, temperatures above 150 0С are widely utilized31. In our previous study, it was found that the use of temperatures in the range of 110–150 ℃ enables the production of ZrO2 nanoparticles with fine size distribution32. However, temperature variation influences the particle size, which in turn induces a phase transition from cubic ZrO2 to monoclinic ZrO2 phase. In that case, no formation of tetragonal phase was observed. Meanwhile, the possibility of achieving the metastable tetragonal phase of ZrO2 through low-temperature hydrothermal synthesis remains an open question. Review of the literature suggests that by selecting different combinations of precursors and mineralizers, one can effectively modify the shape, size, and phase composition of the resulting nanoparticles. At the same time, there is limited information on how technological parameters influence the phase composition of the powders, particularly regarding the content of tetragonal and cubic ZrO2 phases.

The main disadvantages of the resulting ZrO2 nanoparticles include their metastability, high content of water and synthesis by-products33. Since the existence of t – ZrO2 or c – ZrO2 is possible only when the size of nanoparticles is less than 10–20 nm, phase transitions of the type t (or c) – ZrO2 → m – ZrO2 occur during heating and as a consequence of particle growth. Therefore, assessing the phase stability of the synthesized nanoparticles under high-temperature conditions is essential for evaluating their suitability for practical applications.

In this work, the effects of precursor materials and mineralizers on the phase composition of ZrO2 nanoparticles synthesized via low-temperature hydrothermal methods were investigated. XRD and Raman spectroscopy revealed the formation of cubic and tetragonal phases in the samples, depending on the choice of starting materials and mineralizers – a finding highly relevant to the development of materials for energy storage and fuel cells. UV–Vis spectroscopy was used to characterize the optical properties and band gap energies of the synthesized nanoparticles, demonstrating their potential as ultraviolet – absorbing materials. In-situ high-temperature XRD measurements were conducted over a temperature range from room temperature to 1000 0C to identify a suitable operating window for using these nanoparticles as reinforcing additives in ceramics, such as zirconia-toughened alumina (ZTA). Overall, the results of this study may be of interest to researchers involved in the synthesis and application of ZrO2 nanoparticles.

Experimental

ZrO2 nanoparticles were fabricated using the hydrothermal synthesis in a 100 mL stainless steel autoclave equipped with a Teflon liner. Aqueous 0.1 mol/L solutions of zirconyl chloride octahydrate (ZrOCl2·8H2O) (98% purity), zirconyl nitrate dihydrate (ZrO(NO3)3·2H2O) (99% purity), and zirconium(IV) acetate hydroxide ((CH3CO2)xZr(OH)y, where x + y ≈ 4) (99.9% purity) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA, St. Louis) were used as precursors. Aqueous 1 mol/L solutions of NaOH (≥ 85% purity), KOH (≥ 85% purity), and NH4OH (99% purity) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA, St. Louis) prepared with distilled water were used as mineralizers. The resulting solutions were mixed in the proportions necessary to achieve a pH of 9. The Teflon liner was filled to 90% for optimal synthesis processes. An IKA OVEN 125 drying oven (IKA-Werke GmbH & Co. KG, Staufen, Germany) was used to carry out hydrothermal synthesis at 130 0С for 12 h. After removal from the drying oven, the resulting powder was centrifuged five times at 6000 rpm for 5 min and filtered through a paper filter to separate the synthesized particles from residual synthesis by-products (Na, K, Cl, N, C ions and their compounds), followed by drying at 50 0С for 5 h.

Phase composition was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer (Rigaku Corporation, Japan) with CuKα radiation in Bragg–Brentano geometry. The size of the coherent scattering region (CSR) was calculated using the Scherrer Equation34:

where β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) for each of the reflections, \(\:\lambda\:\) wavelength of X-ray radiation (CuKα = 0.15406 нм) 0.9 is a coefficient related to the spherical particles.

The content of monoclinic(\(\:{\nu\:}_{m}\)) and tetragonal (cubic) phase (\(\:{\nu\:}_{t,\:\:c}\)) was estimated using the Equation35:

where reflex intensity ratio (Xm):

where \(\:{I}_{m}\) and \(\:{I}_{t}\) denote the intensities of the respective reflections in the X-ray diffraction pattern.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was employed to examine the morphology and particle size, using a Jeol JEM-1400Plus microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The elemental composition was analyzed using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) integrated into a Phenom ProX G6 scanning electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). Additionally, phase analysis of the fabricated samples was conducted by Raman spectroscopy on an Enspectr M532 spectrometer (Spectr-M LLC, Chernogolovka, Russia) operating at a laser excitation wavelength of 532 nm. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was employed to evaluate the thermal stability and mass loss of the samples under heating. Measurements were performed using a Themys One analyzer (Setaram KEP Technologies, Caluire, France), with samples heated from room temperature to 1000 0C in an argon atmosphere (partial pressure: 0.5 MPa) at a constant rate of 10 0C/min. The optical properties were investigated by UV-visible spectroscopy on a SPECORD 200/210/250 PLUS (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany). The band gap energy Eg was estimated using Tauc plots derived from the corresponding Equation36:

where C is a constant, \(\:\alpha\:\) is absorbance and \(\:h\upsilon\:\) is photon energy.

The phase stability of ZrO2 nanoparticles was studied using high-temperature X-ray diffraction (HTXRD) on a Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer equipped with a Rigaku PTC-40 high-temperature stage (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan). The samples were heated in vacuum from room temperature to 1000 °Cat a heating rate of 10 0C/min. The temperature was increased in 100 °C steps, with a 20-minute hold at each step to record the corresponding diffractogram.

Results and discussion

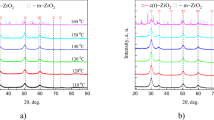

Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns of the synthesized powders, indicating that the choice of precursors and mineralizers significantly affects the phase composition of ZrO2 particles. For example, when NH4OH is used as a mineralizer, regardless of the precursor, the samples exhibit an X-ray amorphous structure. In contrast, if NaOH solution is used as the mineralizer, the samples exhibit high crystallinity and consist entirely (100%, Table 1) of either the tetragonal ZrO2 phase (PDF 00–050 – 1089, space group P42/nmc) or the cubic ZrO2 phase (PDF 01–071 – 6425, space group Fm – 3 m). Using KOH solution as mineralizer, the formation of monoclinic ZrO2 phase (PDF 00–065 – 0687) with the space group of P21/a(14) is observed, along with the presence of tetragonal or cubic ZrO2 phases in samples synthesized from ZrOCl2·8H2O and ZrO(NO3)2·2H2O, respectively. An X – ray amorphous structure was found when NH4OH mineralizer and ((CH3CO2)xZr(OH)y, x + y ~ 4) precursor were used.

These differences may be attributed to the following factors. When ((CH3CO2)xZr(OH)y, x + y ~ 4) is used as precursor and KOH or NH4OH are employed as mineralizers under slightly alkaline conditions (pH ≈ 7–9), the reaction tends to form hydroacetate groups (e.g., Zr(OH)x(CH3COO)4−x) and amorphous gels (e.g., ZrO(OH)2). The hydrolysis of these intermediates and the subsequent formation of ZrO2 particles require higher temperatures and pressures within the autoclave37. In the case of using NaOH as a mineralizer, the acidity of the medium could be affected (pH values were measured with an error of ± 0.5 and were 9 ± 0.5), which could strongly influence the hydrolysis of the precipitate and subsequent crystallization of the particles. When NH4OH is used as a mineralizer under the given conditions, an amorphous ZrO(OH)2 gel is formed. This gel is less hydrated and therefore more stable under hydrothermal conditions compared to Zr(OH)4, which forms when NaOH or KOH are used. As a result, the crystallization process requires higher temperatures and longer synthesis durations. Thus, the phase composition of the particles is influenced by the reaction progress and the precipitate that is subjected to hydrothermal treatment.

Using Eq. (1), the coherent scattering region (CSR) values, which represent the minimum particle size in the sample, were calculated for the crystalline samples listed in Table 1. Samples containing only the tetragonal or cubic ZrO2 phase exhibit CSR values in the range of 5–8 nm. In contrast, samples that also contain the monoclinic phase show CSR values of approximately 8 nm for the tetragonal (or cubic) phase and 10–20 nm for the monoclinic phase, with the latter increasing as the proportion of the monoclinic phase grows. It is known that the formation of high-temperature tetragonal and cubic ZrO2 phases at room temperature without doping is attributed to the high surface energy of nanoparticles. This effect is typically observed when particle sizes fall within the critical range of 10–20 nm. Therefore, it can be concluded that, under the given synthesis conditions, the nature of the precipitate influences the rate of hydrolysis and subsequent decomposition of hydroxide groups, resulting in variations in particle size and phase transformations during the crystallization of ZrO2 within the autoclave.

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy revealed that samples synthesized using NaOH as a mineralizer contain Na, whereas those prepared with KOH or NH4OH do not exhibit the presence of synthesis – related by – product elements. This observation can be attributed to the lower solubility of sodium compounds in water compared to those of potassium and ammonium. Additionally, sodium tends to form stable precipitates such as NaOH, Na2CO3 NaNO3, and Na2ZrO3, which are difficult to remove from the synthesized powder. The elemental ratio between Zr and O is close to stoichiometric, with minor deviations connected to the overlap of the EDX peaks of oxygen and gold, as well as surface inhomogeneity of the nanoparticles.

Due to the close similarity between the crystal structures of tetragonal and cubic zirconium dioxide (especially for nanoparticles), it is impossible to exactly determine which of the two phases is present in the sample using X – ray diffraction. Raman spectroscopy enables reliable differentiation between tetragonal and cubic ZrO2 phases based on their distinct vibrational modes. In contrast to the XRD patterns, where some powders appeared amorphous, the Raman spectra of all samples (Fig. 2) indicate the presence of a crystalline structure. These discrepancies can be explained by the higher sensitivity of Raman spectroscopy to the local and short-range crystal structure of a material. As a result, the synthesized samples may lack long – range order and instead exist in a form of an amorphous matrix with relatively small crystalline inclusions38. Additionally, it can be assumed that this is related to the XRD detection of the material as amorphous if the particle size is less than 5 nm39. It can be accepted that samples characterized by an amorphous structure from XRD contain crystalline nucleates, which are identified on Raman spectra and are not visible on diffractograms. Samples obtained using NaOH as a mineralizer show the presence of a vibrational mode in the region of 500–600 cm− 1, characteristic of the c – ZrO2 phase40,41. In contrast, when KOH is used as a mineralizer, all samples demonstrate Raman modes at 147, 260, 316, 466, and 640 cm− 1 characteristic of t – ZrO2 phase42,43 and modes at 177, 188, 220, 306, 330, 342, 380, 477, 537, 556, and 609 cm− 1 representative of m – ZrO2 phase44,45. It should also be noted that when NH4OH is used as a mineralizer, depending on the precursor, the presence of different combinations of ZrO2 phases is observed. Thus, when ZrOCl2·8H2O and ((CH3CO2)xZr(OH)y, x + y ~ 4) are used as starting materials (Fig. 2a and c), the cubic ZrO2 phase is detected, whereas the use of ZrO(NO3)2·2H2O (Fig. 2b) resulted in the formation of monoclinic and tetragonal phases. The presence of different anions in the synthesis medium, particularly chloride anions (Cl−), can affect the surface energy of particles and inhibit the transition to a more stable phase such as monoclinic or tetragonal37.

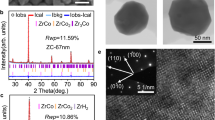

Figure 3 illustrates the most representative TEM-images for each group of samples. Analysis of TEM images revealed that the crystalline single-phase samples (Figs. 1S and 3a (a, d, g) in the Supplementary Information) exhibit a spherical morphology with particle sizes ranging from 4 to 14 nm, and a predominant size distribution in the range of 5–6 nm, which is in good agreement with the CSR values. In addition, two-phase crystalline samples (Figs. 1S and 3b (b, e) in supplementary) contain both small particles ranging from 5 to 10 nm and larger particles in the 100–200 nm range. This difference in particle sizes can be explained by the simultaneous presence of m – ZrO2 and t – ZrO2 phases. The samples exhibit an X-ray amorphous structure (Figs. 1S and 3c (c, f, h, i) in supplementary) with small crystalline inclusions of 5–10 nm in size, which confirms the Raman spectroscopy data on the presence of a crystalline structure.

TGA method was used to evaluate the presence of synthesis by-products in the samples. Figure 4 demonstrates that the content of residual products in the samples is significantly affected by both the precursor and the mineralizer. The mass loss process can generally be divided into four regions: (1) evaporation of physically adsorbed water in the range from room temperature to 200 0C; (2) removal of chemically adsorbed water between 200 °C and 400 °C; (3) decomposition of -OH groups and their compounds from 400 °C to 600 °C; and (4) elimination of synthesis by-products, such as NaOH, Na2CO3, KCl, and NaNO3, occurring between 600 and 800 °C26,46,47. The significant variation in mass loss upon heating is attributed to the differences in the synthesized nanoparticles. The highest mass losses were observed in samples synthesized using ((CH3CO2)xZr(OH)y, x + y ~ 4), as the resulting powder contained hydroacetate groups that decompose and evaporate upon heating. A similar trend of significant mass loss is observed when ZrOCl2·8H2O or ZrO(NO3)2·2H2O are used as precursors in combination with NH4OH as the mineralizer.

The optical properties of the synthesized ZrO2 nanoparticles were investigated using UV-Vis spectroscopy. It can be seen from Fig. 5 that the absorption spectra are characterized by steps and shoulder starting from absorption peak in the region of λ = 200 nm, which is related to the band gap energy48. When nitrate and chloride are used as precursors, the samples synthesized with KOH as the mineralizer exhibit the highest transmittance in the measured wavelength range, particulary in the region of 250 to 300 nm. Also, these samples showed the lowest mass loss, indicating a low content of synthesis by-products. It can be assumed that the absorption in the ultraviolet range is related both to the size of the particles (which can be indirectly estimated from X-ray diffractograms by the presence of the monoclinic phase) and the amount of by-products (more than 9%. If ((CH3CO2)xZr(OH)y, x + y ~ 4) was used as the precursor and NH4OH or NaOH as mineralizers, synthesis by-products (zirconium acetates, chlorides, nitrides) could contribute to the absorption in the UV range. For example, the highest absorbance can be attributed to the presence of chlorides in samples with the NaOH mineralizer, which may have an absorption peak in the 200–300 nm region49. The Tauck plots obtained using Eq. (3), as shown in Fig. 2S in the Supplementary Information, indicate differences in band gap energies (Table 1) that do not correlate with changes in synthesis parameters. This suggests that the observed variations in band gap values may result from the presence of different synthesis by-products.

Phase stability analysis using high-temperature X-ray diffraction (Fig. 6 in the main text and Fig. 3S in the Supplementary Information) revealed that the initially crystalline samples (Fig. 3S (a, b, d, e, g)) remain stable up to 800 0C. Above this temperature, a notable decrease in the content of tetragonal and cubic ZrO2 phases is observed (calculated using Eq. (2)), accompanied by an increase in the monoclinic ZrO2 phase content. As mentioned earlier, this behavior is associated with particle coarsening beyond the critical size required for the stability of high-temperature phases. CSR values calculated from the HTXRD data show that for the tetragonal and cubic ZrO2 phases, the sizes range from 6 to 8 nm and remain nearly unchanged upon heating up to 800 0C. In contrast, the CSR values for the monoclinic ZrO2 phase lie within the range of 12 to 30 nm and increase with the growing proportion of this phase. For the initially amorphous samples (Fig. 3S (c, f, h, i)), the powders remain amorphous up to temperatures of 400–600 0C. As the temperature increases further, gradual crystallization occurs, evidenced by the appearance of diffraction peaks and the progressive increase in their intensities. The crystallized ZrO2 particles consist exclusively of the tetragonal (or cubic) phase and exhibit CSR sizes ranging from 8 to 14 nm. Further increase in temperature leads to a gradual increase in CSR values up to 16–30 nm and progressive phase transformation of the following type: t (or c) – ZrO2 → m – ZrO2. In contrast to the other powders, the sample synthesized using ((CH3CO2)xZr(OH)y, x + y ~ 4) as the precursor and KOH as the mineralizer (red dashed line in Figs. 3S – h and 6c) does not undergo phase transformations at 1000 ℃, which is attributed to its delayed crystallization.

To identify which phases were formed during crystallization of initially amorphous samples, their Raman spectra after HTXRD were taken (Fig. 7). The presented data indicate that tetragonal ZrO2 phase is formed during crystallization of amorphous samples. The discrepancies between the X-ray diffraction data at 1000 °C, where peaks corresponding to the monoclinic ZrO2 phase are not observed in samples synthesized from ((CH3CO2)xZr(OH)y, x + y ~ 4) using KOH and NH4OH as mineralizers, and the Raman spectroscopy results obtained after cooling may be explained by continued growth and sintering of nanoparticle agglomerates during the cooling stage. This highlights the influence of not only the annealing temperature but also the duration of thermal exposure in governing phase formation in ZrO2.

Conclusions

In this work, ZrO2 nanoparticles were synthesized via a low – temperature hydrothermal method using various precursor materials and mineralizers. XRD and Raman spectroscopy demonstrated that the choice of precursor and mineralizer has a significant impact on the phase composition of the synthesized nanoparticles. It was found that using NaOH as the mineralizer regardless of the precursor the cubic ZrO2 phase formed, whereas NH4OH produces an X-ray amorphous structure with crystalline nuclei, as revealed by Raman spectroscopy. Using KOH in combination with ZrOCl2·8H2O or ZrO(NO3)2·2H2O leads to the formation of tetragonal and monoclinic ZrO2 phases. These pronounced differences in phase composition arise from changes in the chemical processes within the autoclave, the rate of precipitate hydrolysis, and consequently the rates of nucleation and subsequent crystallization. The coherent scattering region (CSR) values for single – phase crystalline samples ranged from 5 to 8 nm, whereas samples with mixed phases exhibited CSR values between 10 and 20 nm. CSR values calculated from XRD data correlate well with TEM observations: the average particle size for single – phase crystalline samples was in the range between 4 and 14 nm, with a maximum concentration around 5–6 nm. TEM images also confirmed the presence of crystalline nuclei in samples with X-ray amorphous structure. The as-synthesized ZrO2 nanoparticles contained a substantial amount of residual by-products (H2O, –OH groups, Na2CO3, NaNO3, etc.), totaling up to 30%. UV–Vis spectroscopy revealed strong ultraviolet absorption for particles synthesized with NaOH. In cases where hydroacetate groups and amorphous gels formed as by-products, the optical behavior differed markedly from that of pure ZrO2 nanoparticles. Phase-stability analysis by in-situ HTXRD showed that initially crystalline ZrO2 nanoparticles remain phase-stable up to 700–800 0C; above this range, the content of tetragonal or cubic ZrO2 drops sharply due to grain growth beyond the critical size needed to stabilize high-temperature phases in the absence of dopants. Conversely, initially amorphous powders crystallized between 400 and 600 0C into purely tetragonal ZrO2, which gradually transformed into the monoclinic phase upon further heating, as confirmed by Raman spectroscopy.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kumari, S., Sharma, E., Verma, J., Dalal, J. & Kumar, A. Structural and photoluminescence properties of Dy-doped nanocrystalline ZrO2 for optoelectronics application. Ceram. Int. 49, 20185–20192 (2023).

Doroshkevich, A. S. et al. Electric Energy Storage Effect in Hydrated ZrO2-Nanostructured System. Nanomaterials 12, (2022).

Fathima, J. B., Pugazhendhi, A. & Venis, R. Synthesis and characterization of ZrO2 nanoparticles-antimicrobial activity and their prospective role in dental care. Microb. Pathog. 110, 245–251 (2017).

Bansal, P., Kaur, N., Prakash, C. & Chaudhary, G. R. ZrO2 nanoparticles: an industrially viable, efficient and recyclable catalyst for synthesis of pharmaceutically significant Xanthene derivatives. Vacuum 157, 9–16 (2018).

Zahra, T. et al. Electrocatalytic water splitting studies on zirconium oxide nanoparticles synthesized by biomimetic synthesis route. Ionics (Kiel). 29, 5339–5352 (2023).

Caillot, T. et al. Hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of zirconia based catalysts. J. Solid State Chem. 203, 79–85 (2013).

Tuan, W. H., Chen, R. Z., Wang, T. C., Cheng, C. H. & Kuo, P. S. Mechanical properties of Al2O3/ZrO2 composites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 22, 2827–2833 (2002).

Kul’kova, S. E. & Muryzhnikova, O. N. Electronic structure and optical properties of zirconia. Inorg. Mater. 36, 38–42 (2000).

Farhan Hanafi, M. & Sapawe, N. Effect of calcination temperature on the structure and catalytic performance of ZrO2 catalyst in phenol degradation. Mater. Today Proc. 19, 1533–1536 (2019).

French, R. H., Glass, S. J., Ohuchi, F. S., Xu, Y. N. & Ching, W. Y. Experimental and theoretical determination of the electronic structure and optical properties of three phases of ZrO2. Phys. Rev. B. 49, 5133–5142 (1994).

Kumari, N. et al. Zirconia-based nanomaterials: recent developments in synthesis and applications. Nanoscale Adv. 4, 4210–4236 (2022).

Shakirzyanov, R. I. et al. Exploring the influence of sintering temperature on the phase composition, mechanical strength, and dielectric constant of porous ca-stabilized zirconium dioxide ceramics. Discov Mater. 4, 48 (2024).

Tian, D. et al. Performance of cubic ZrO2 doped CeO2: First-principles investigation on elastic, electronic and optical properties of Ce1 – x ZrxO2. J. Alloys Compd. 671, 208–219 (2016).

Fujii, S., Shimazaki, K. & Kuwabara, A. Empirical interatomic potentials for ZrO2 and YSZ polymorphs: application to a tetragonal ZrO2 grain boundary. Acta Mater. 262, 119460 (2024).

Tsunekawa, S., Kawazoe, Y., Kojima, T. & Sugimoto, T. Fabrication of zirconium oxide nanocrystallites and the critical size of the phase transition. Int. J. Nanosci. 05, 651–656 (2006).

Shukla, S., Seal, S. & and Mechanisms of room temperature metastable tetragonal phase stabilisation in zirconia. Int. Mater. Rev. 50, 45–64 (2005).

Honda, A., Kimura, T., Ito, A. & Goto, T. Rh-nanoparticle-dispersed ZrO2 films prepared by laser chemical vapor deposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 206, 3006–3010 (2012).

Khalili, S. & Chenari, H. M. Successful electrospinning fabrication of ZrO2 nanofibers: A detailed physical – chemical characterization study. J. Alloys Compd. 828, 154414 (2020).

Deshmane, V. G. & Adewuyi, Y. G. Synthesis of thermally stable, high surface area, nanocrystalline mesoporous tetragonal zirconium dioxide (ZrO2): effects of different process parameters. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 148, 88–100 (2012).

Tran, T. et al. Green synthesis of ZrO2 nanoparticles and nanocomposites for biomedical and environmental applications: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 20, 1309–1331 (2022).

Salavati-Niasari, M., Dadkhah, M. & Davar, F. Pure cubic ZrO2 nanoparticles by thermolysis of a new precursor. Polyhedron 28, 3005–3009 (2009).

Ordóñez, F., Chejne, F., Pabón, E. & Cacua, K. Synthesis of ZrO2 nanoparticles and effect of surfactant on dispersion and stability. Ceram. Int. 46, 11970–11977 (2020).

Arantes, T. et al. Stable colloidal suspensions of nanostructured zirconium oxide synthesized by hydrothermal process. J. Nanopart. Res. 12, 3105–3110 (2010).

Pei, L. Z., Xie, Y. K., Pei, Y. Q. & Yuan, C. Z. Synthesis and formation process of zirconium dioxide nanorods. Mater. Science-Poland. 31, 186–192 (2013).

Liu et al. Supercritical Hydrothermal Synthesis of Nano-Zirconia: Reaction Path and Crystallization Mechanisms of Different Precursors. E3S Web of Conf. 406, 1025 (2023).

Mohsen, Q. et al. Effect of pH on hydrothermal synthesis of ZrO2 nanoparticles and their electrocatalytic activity for hydrogen production. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 17, 22073 (2022).

Liu, L., Wang, S., Zhang, B., Jiang, G. & Yang, J. Supercritical hydrothermal synthesis of nano-ZrO2: influence of technological parameters and mechanism. J. Alloys Compd. 898, 162878 (2022).

Yang, G. & Park, S. J. Conventional and microwave hydrothermal synthesis and application of functional materials: A review. Materials 12, 1177 (2019).

Tani, E., Yoshimura, M. & Sōmiya, S. Formation of ultrafine tetragonal ZrO2 powder under hydrothermal conditions. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 66, 11–14 (1983).

Li, C. et al. Effect of reaction temperature on crystallization of nanocrystalline zirconia synthesized by microwave-hydrothermal process. J. Alloys Compd. 561, 23–27 (2013).

Saddam Husain, M., Pandey, V., Ahmed, H., Ahmad, T. & Munjal, S. Structural and optical analyses of hydrothermally synthesized ZrO2 nanopowder. Mater. Today Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MATPR.2023.06.079 (2023).

Garanin, Y. et al. Study of morphology, phase composition, optical properties, and thermal stability of hydrothermal zirconium dioxide synthesized at low temperatures. Sci. Rep. 14, 29398 (2024).

Thakur, M., Vij, A., Singh, F. & Rangra, V. S. Spectroscopic studies of metastable tetragonal ZrO2 nanocrystals. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 305, 123495 (2024).

Szepesi, C. J. & Adair, J. H. High yield hydrothermal synthesis of Nano-Scale zirconia and YTZP. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 94, 4239–4246 (2011).

Toraya, H., Yoshimura, M. & Somiya, S. Calibration curve for quantitative analysis of the Monoclinic-Tetragonal ZrO2 system by X-Ray diffraction. Journal Am. Ceramic Society 67, C-119-C-121. (1984).

Horti, N. C., Kamatagi, M., Sanna Kotrappanavar, N., Wari, M. N. & Inamdar, S. Structural and optical properties of zirconium oxide (ZrO2) nanoparticles: effect of calcination temperature. Nano Express 1, 010022 (2020).

Wang, H., Li, G., Xue, Y. & Li, L. Hydrated surface structure and its impacts on the stabilization of t-ZrO2. J. Solid State Chem. 180, 2790–2797 (2007).

Deluca, M., Hu, H., Popov, M. N., Spitaler, J. & Dieing, T. Advantages and developments of Raman spectroscopy for electroceramics. Commun. Mater. 4, 78 (2023).

Holder, C. F. & Schaak, R. E. Tutorial on powder X-ray diffraction for characterizing nanoscale materials. ACS Nano. 13, 7359–7365 (2019).

Cai, J., Raptis, Y. S. & Anastassakis, E. Stabilized cubic zirconia: A Raman study under uniaxial stress. Appl. Phys. Lett. 62, 2781–2783 (1993).

Hemberger, Y., Wichtner, N., Berthold, C. & Nickel, K. G. Quantification of Yttria in stabilized zirconia by Raman spectroscopy. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 13, 116–124 (2016).

KELLY, P. M. & BALL, C. J. Crystallography of Stress-Induced martensitic transformations in partially stabilized zirconia. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 69, 259–264 (1986).

Yi, M. et al. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Activity of ZrO2 Nanoparticles: Effect of Tetragonal and Monoclinic Phases. Nanomaterials 11, (2021).

Arashi, H. & Ishigame, M. Raman spectroscopic studies of the polymorphism in ZrO2 at high pressures. Phys. Status Solidi (a). 71, 313–321 (1982).

Sakfali, J. et al. High photocatalytic activity of aerogel tetragonal and monoclinic ZrO2 samples. J. Photochem. Photobiol Chem. 430, 113970 (2022).

Sigwadi, R., Mokrani, T. & Dhlamini, M. The synthesis, characterization and electrochemical study of zirconia oxide nanoparticles for fuel cell application. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 581, 411842 (2020).

Broström, M., Enestam, S., Backman, R. & Mäkelä, K. Condensation in the KCl–NaCl system. Fuel Process. Technol. 105, 142–148 (2013).

Majedi, A., Abbasi, A. & Davar, F. Green synthesis of zirconia nanoparticles using the modified pechini method and characterization of its optical and electrical properties. J. Solgel Sci. Technol. 77, 542–552 (2016).

Tong, A., Tang, X., Zhang, F. & Wang, B. Study on the shift of ultraviolet spectra in aqueous solution with variations of the solution concentration. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 234, 118259 (2020).

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (No. BR21882390).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G, R.S., N.V., D.S., M.Z. and D.B.; methodology, Y.G., R.S., N.V., D.S., M.Z. and D.B.; formal analysis, Y.G., R.S., N.V., D.S., M.Z. and D.B.; investigation, Y.G., R.S., N.V., D.S., M.Z. and D.B.; resources, D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, review, and editing, Y.G, R.S. and N.V.; visualization, D.B. and Y.G.; supervision, D.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Garanin, Y., Shakirziyanov, R., Borgekov, D. et al. Influence of precursors and mineralizers on phase formation in ZrO2 nanoparticles synthesized by the hydrothermal method. Sci Rep 15, 26165 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12213-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12213-1