Abstract

Pediatric gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis (GIB) is a rare fungal infection caused usually caused by Basidiobolus ranarum. It primarily affects individuals in tropical and subtropical regions. This study aims to present clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic insights from a comprehensive bicentric retrospective case series in Saudi Arabia. We retrospectively analyzed pediatric GIB cases from two tertiary hospitals in Jazan and Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Data included demographics, clinical presentations, diagnostic approaches, treatment modalities, and outcomes. Diagnosis was based on clinical presentation, epidemiological context, and histopathological findings, with or without microbiological workup and fungal isolation. In this series, 42 cases were included with about 64% of cases being male and 76% aged six years or younger. Most cases were from Jazan Province, a southwestern region with tropical climatic features and extensive agricultural activities. The bowel was the most affected organ (90.47%), followed by the liver (29%). The diagnosis was initiated by clinical suspicion and relied predominantly on histopathological findings, as fungal culture was rarely done or yielded positive. About 83% of cases responded to voriconazole monotherapy, while 33% required surgical intervention. Relapse occurred in two patients, and one had persistent infection, all with hepatic involvement. Notably, no mortality was observed in this cohort. This study highlights the importance of early recognition and antifungal therapy in achieving favorable outcomes in pediatric GIB. Voriconazole monotherapy is highly effective, and cases can become complicated when the liver is involved. Further studies are required to streamline diagnostic workflows and optimize treatment protocols, including identifying factors that influence relapse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pediatric gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis (GIB) is an emerging fungal infection caused usually by Basidiobolus ranarum, an environmental saprophyte found in soil and decaying plant materials1,2. Basidiobolus spp. were previously classified under the class Zygomycetes but have been recently reclassified under the order Entomophthorales1,2,3. The exact pathogenesis of GIB remains unclear, but the most widely accepted theory suggests infection occurs through ingesting contaminated soil or food2,3,4.

GIB predominantly may affect immunocompetent individuals in tropical and subtropical regions2,3. The disease commonly presents as a chronic subcutaneous infection as the first human case was reported as a subcutaneous infection in Indonesia in 1956, while in 1964, the first presumed case of pediatric GIB was reported in a 6-year-old Nigerian boy5. Globally, GIB has a higher prevalence among pediatric patients from tropical and subtropical regions6,7. To date, 61 cases have been reported, with the highest number from Saudi Arabia (35 cases)4,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, followed by Iran (19 cases)24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, Brazil, and Iraq (two cases each)33,34,35, and single cases reported from Nigeria, Qatar, and Oman36,37,38,39. Most cases in Saudi Arabia originate from regions with tropical and subtropical climates3,40,41.

GIB poses a significant diagnostic challenge due to its ability to mimic neoplastic diseases, abdominal tuberculosis, or inflammatory bowel disorders4,7,8,41. Initial diagnostic imaging often reveals abdominal masses or bowel wall thickening, prompting further evaluation. However, biopsies obtained through colonoscopy may return negative for fungal infection, likely due to the deep mucosal localization of B. ranarum, which prevents its detection in superficial tissue samples4,41.

Despite the gold standard for GIB diagnosis being the isolation of B. ranarum in culture, this is not routinely yielding positive results. Instead, diagnosis is primarily based on clinical presentation, epidemiological link, radiological and histopathological findings from tissue specimens, which typically show chronic granulomatous inflammation with broad, non-septate, hyphae-like structures surrounded by an eosinophilic sheath, also known as the Splendore–Hoeppli phenomenon40.

Historically, before the availability of voriconazole, early surgical resection combined with systemic antifungal therapy was considered the optimal management approach42. However, more recent cases have demonstrated successful outcomes with antifungal voriconazole monotherapy alone9,41,43. In this study, we retrospectively report cases presented pediatric GIB cases from the two centers in the country located in the center and southwestern region. We aim to enhance understanding of this emerging disease, document the efficacy of antifungal monotherapy, and evaluate clinical outcomes.

Methodology

Study design and setting

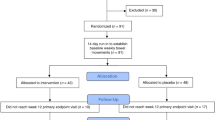

This study is a bicentric retrospective analysis conducted at King Fahad Central Hospital (KFCH) in Jazan and King Faisal Specialist Hospital and research center (KFSH&RC) in Riyadh. Both hospitals serve as tertiary care centers, catering to diverse populations across Saudi Arabia. KFCH was selected as it is the primary referral hospital for the Jazan region, which has a high prevalence of pediatric GIB cases due to its tropical climate and agricultural environment of the region. Historically, most reported cases in Saudi Arabia have originated from this region. KFSH&RC was included as it serves as a national referral center for complex and refractory cases, receiving patients from across the country who require advanced diagnostics and specialized management. This selection allows for a comprehensive analysis of both regionally prevalent and referred cases, ensuring a more representative understanding of disease patterns and treatment outcomes. The study focused on pediatric patients diagnosed with GIB over 20 years from 2002 to 2022, aiming to assess demographics, clinical features, laboratory findings, diagnostic methods, treatment approaches, and outcomes.

Participants, inclusion, and exclusion criteria

Patients aged 0–14 years with confirmed or suspected GIB were included. The diagnosis was established based on histopathological findings, such as the presence of the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon, characterized by chronic granulomatous inflammation and broad, non-septate hyphae-like structures surrounded by an eosinophilic sheath as reported by histopathology. Fungal culture, specifically the isolation of Basidiobolus ranarum from biopsy samples, when available is considered as additional confirmatory criterion. Criteria of suspected cases include epidemiological context, compatible clinical and radiological signs with excluded other differential diagnoses, however, these cases lacked histological or culture confirmation. Patients with incomplete records or alternative confirmed diagnoses were excluded. Molecular testing was not available at the time of the study.

Data collection

Data were extracted from electronic medical records from both hospitals and included a range of variables. Data extraction was conducted for cases recorded between 2002 and 2022. Demographic data comprised age, sex, and geographic location. Clinical features included symptoms, the duration of illness, and organ involvement. Laboratory findings focused on absolute eosinophil count (AEC) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Diagnostic methods included histology, culture, or clinical criteria, while treatment modalities were categorized into antifungal therapy, surgical interventions, and treatment duration. Finally, outcomes were documented as a cure, relapse, persistent disease, or death.

Diagnostic and treatment protocols

Patients might undergo diagnostic evaluations, including radiological imaging, endoscopy, and biopsy. Fungal cultures were performed when feasible or requested. Treatment regimens primarily included antifungal monotherapy or combination therapy, with surgical interventions in selected cases based on organ involvement or disease severity.

Ethical considerations

The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical guidelines for scientific research in Saudi Arabia and was approved by the institutional review boards of both centers, i.e. KFSH&RC and KFCH. Patient confidentiality was strictly maintained, and no identifiable information was recorded.

Results

A total of 42 pediatric patients diagnosed with GIB were included in this study. The age distribution showed that the majority (42.86%) were between 2 and 4 years, followed by 33.33% in the 5 to 6-year range, and 23.81% between 7 and 14 years. Males constituted a larger proportion of the cohort (64.29%) compared to females (35.71%) (Table 1). The most frequently involved organ was the bowel, affected in 69.05% of cases, followed by concurrent bowel and liver involvement in 19.05%, isolated liver involvement in 9.52%, and bowel and bladder involvement in 2.38%. The primary method of diagnosis was histopathological examination (85.71%), while 9.52% of cases were confirmed by both histology and culture and only 4.76% was diagnosed based on clinical suspicion alone. Almost all patients underwent plain or contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen. The most common abnormality with bowel involvement was bowel wall thickening. When other organs were involved, they usually appeared as masses. Reactive lymphadenopathy was occasionally noticed in some patients.

Laboratory analysis revealed variations in AEC and ESR (Table 2). Nearly 40.48% of patients had an AEC within the normal range (0 to 1 × 10³/µL), while 38.10% exhibited mild eosinophilia (2 to 4 × 10³/µL), and 21.43% had an AEC ranging from 4 to 8 × 10³/µL. ESR levels were elevated in most patients, with 41.03% having values between 50 and 120 mm/hr and 15.38% exceeding 120 mm/hr. A moderate ESR increase (3 to 47 mm/hr) was observed in 43.59% of cases.

Regarding treatment strategies, 66.67% of patients received antifungal therapy alone, while 33.33% underwent a combination of medical and surgical management (Table 3). Voriconazole (recommended dose: 7–9 mg/kg/dose twice daily) was the primary antifungal agent used in 83.33% of cases, while 2.38% were treated with itraconazole (recommended dose: 5 mg/kg/dose twice per day), and 14.29% received a combination of both antifungals. The duration of antifungal therapy varied, with 48.65% of patients completing treatment within 12 months, whereas 51.35% required prolonged therapy exceeding one year. Outcomes were favorable in most cases, with 92.86% achieving full recovery from the first trial. Two patients experienced a relapse but were eventually cured with continued treatment and adding trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. However, one patient exhibited persistent infection with a very slow response despite two years of voriconazole treatment and combination with trimethoprim-sulfa combination and later ceased the follow-up in the clinic suddenly.

Discussion

Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis (GIB) is a rare but increasingly recognized fungal infection, particularly among pediatric patients in tropical and subtropical regions. The first documented pediatric case was reported in 1964 in a 6-year-old Nigerian boy38. Since then, advancements in healthcare awareness and diagnostic capabilities have enhanced early detection, contributing to an increase in reported cases. Various studies have reported pediatric GIB in Saudi Arabia and globally, and the findings of these studies are summarized in Table 4 and compared with the current experience.

A comparison between our study cohort (Group 1 = 42 cases) and previously published cases, before 2020, (Group 2 = 54 cases) reveals notable differences and trends (Table 4). In our study, 64% of cases were male, with 76% being six years old or younger. Similarly, in Group 2, males constituted 91% of cases, and 70% were within the same age bracket. This predominance of younger males may be attributed to increased outdoor exposure for this population, leading to more interaction with environmental sources of Basidiobolus ranarum41. Most cases originated from Jazan Province, a region characterized by a warm, humid climate and extensive agricultural activity, huge mountainous and seaside areas, providing an ideal habitat for fungal growth41. The clinical manifestations of GIB in our study align with previously reported patterns. The bowel was the most commonly affected organ, involved in 69% of cases in Group 1 and 72% in Group 2. Hepatic involvement was observed in 10% and 13% of cases in Groups 1 and 2, respectively, while bowel and liver co-involvement occurred in 19% and 17% of cases. Notably, the disseminated disease was present in 20% of cases in Group 2 but was significantly less frequent in Group 1 (2%), suggesting improved early detection and management in recent years and both centers are considered referral centers in the region.

Despite the availability of fungal culture in most of the laboratories of the referral centers in the country and being reported as the gold standard for diagnosing GIB3, it was not commonly yielded positive in cases of GIB with, only four cases in our study reporting positive results. Instead, diagnosis predominantly relied on histopathological examination. Although the characteristic Splendore–Hoeppli phenomenon is considered a hallmark of basidiobolomycosis, it can also be seen in certain bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections. However, in our cohort, the identification of broad, aseptate fungal hyphae within tissue specimens, combined with the accumulated diagnostic experience of our pathologists in recognizing GIB, supported the histopathological diagnosis. Moreover, the favorable clinical response to antifungal therapy in nearly all cases further minimized the likelihood of false-positive diagnoses. Histology-based diagnosis was used in 93% of Group 1 cases and 100% of Group 2 cases. However, in some instances within Group 1, histological confirmation was not feasible due to parental refusal of invasive procedures or minimal mucosal thickening reported by radiologists and contraindicating biopsy. These patients were managed empirically based on clinical and radiological findings, with subsequent improvement upon antifungal therapy initiation. Elevated inflammatory markers were frequently observed in GIB cases, with eosinophilia and ESR noted in over half of our patients. Although PCR has been shown to offer high sensitivity and specificity in detecting B. ranarum3,40, it remains underutilized and was not performed in our cohort as it was not available at the time of the study. Future studies should explore its role in streamlining diagnostic workflows.

Over the years, the management of pediatric GIB has evolved. Historically, surgical resection followed by antifungal therapy was the preferred approach41,42,43. In our study, antifungal monotherapy was the primary treatment in 67% of cases, while 33% required a combination of surgery and medical management. This contrasts with Group 2, where 55% of patients underwent surgical resection, highlighting a shift towards less invasive strategies in more recent cases41,44,45. Voriconazole was the most frequently used antifungal in Group 1 (83%), followed by itraconazole (2%). In contrast, Group 2 predominantly received itraconazole (41%), with amphotericin B used in 46% of cases30. The preference for voriconazole in recent cases may reflect improved accessibility and superior clinical outcomes9,41. In general, the frequent use of voriconazole and itraconazole in GIB in both groups was usually associated with good prognosis especially if used earlier in the course.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was successfully used in two of our patients with refractory or relapsing disease. However, in one patient with persistent infection and a slow response to voriconazole monotherapy over two years, the addition of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole did not lead to a faster recovery. A study from Iran reported three patients who were treated with a combination of itraconazole and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, with or without amphotericin B28. Additionally, patients with refractory and disseminated disease was effectively treated with potassium iodide30,45,46. These cases highlight the need for further investigation into the potential role of these alternative therapies in GIB treatment.

The duration of antifungal therapy used in our study ranged from 10 to 33 months with approximately half of the patients in group 1 receiving treatment for 12 months or less7,9,10. This marks a shift from historical cases, where very prolonged intravenous antifungal therapy was practiced24. The observed trend toward earlier initiation of oral therapy has led to excellent outcomes and reduced treatment burdens24. Hepatic involvement has been associated with an increased risk of relapse and poor outcomes42,46. In a prior study, two out of 19 cases with liver involvement resulted in mortality42. In our study, both relapsed and persistent cases had hepatic involvement, emphasizing the need for extended monitoring in such patients. A striking difference was observed in mortality rates between the two groups. While Group 2 had a 25% mortality rate, no deaths were reported in Group 1. Additionally, three patients in Group 2 succumbed to the disease before receiving a definitive diagnosis34,36. Delayed presentation or detection of GIB appears to increase the likelihood of hepatic dissemination, prolong the duration of treatment, and elevate mortality rates. Utilizing non-invasive diagnostic modalities, such as interventional radiology for biopsy extraction in suspected GIB cases, may help reduce mortality observed in patients who undergo surgical resection for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. However, surgical resection of the affected liver segment should be reconsidered in refractory cases or patients experiencing significant adverse effects from medication. Most of the recently reported cases from Saudi Arabia have followed a similar diagnostic and therapeutic approach, typically resulting in excellent prognoses. Several factors likely contributed to this improved prognosis in our centers, including enhanced physician awareness, earlier diagnosis with non-invasive diagnostic tools, accumulated experience in both centers and the early shift toward antifungal monotherapy, reducing the risks associated with surgical intervention. Such variations in morbidity, mortality, diagnosis, and management modalities highlight the need for health officials to establish national guidelines that ensure the implementation of the best and most up-to-date practices.

One unique case in our cohort involved a patient presenting with jaundice, direct hyperbilirubinemia, and elevated liver enzymes. Abdominal imaging revealed circumferential thickening of the ascending colon, and a biopsy by interventional radiology confirmed basidiobolomycosis. Despite initiating voriconazole therapy, liver enzyme levels remained elevated, necessitating dose adjustments and the introduction of ursodeoxycholic acid. Upon completing the antifungal course, the patient’s liver enzymes and bilirubin rebounded without signs of GIB relapse, prompting further evaluation. Whole exome sequencing ultimately led to a diagnosis of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 3. This case indicates the additional complexity of managing GIB in patients with underlying genetic hepatic disorders. Furthermore, in one case with persistent GIB reported from Jazan, whole-exome sequencing followed by whole-genome sequencing were obtained to explore the expected underlying immune deficiency, but the results were insignificant.

Limitation

Despite the rarity of reported pediatric GIB cases, this study analyzes a large number of cases and compares them with previously documented pediatric cases. However, certain limitations exist. As these cases were collected over several years, each presenting with different clinical features, requested investigations and treatment plans, this study might have faced some reporting bias and missing data and we were unable to establish a consistent trend regarding the optimal antifungal dosage and duration. Notably, our findings suggest a distinction between two distinct eras, before and after the availability of voriconazole. In the earlier period, treatment relied on itraconazole or amphotericin B, often necessitating surgical intervention due to suboptimal therapeutic responses. In contrast, the later era, characterized by the availability of voriconazole, demonstrated improved outcomes with a reduced need for surgical management. Additionally, determining the precise correlation between treatment regimens and the type or extent of organ involvement remained challenging. The study also faced difficulties in defining clear criteria for monitoring patient improvement and determining when therapy should be discontinued, whether based solely on clinical evaluation or in conjunction with laboratory tests and radiological studies. Furthermore, due to the limited number of relapsing cases, it was difficult to ascertain whether relapses were primarily attributed to disease dissemination, antifungal resistance, or underlying immune deficiencies. Further, Group 2 included all cases published before 2020 to ensure consistency in diagnostic and treatment approaches, avoid disruptions related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and allow for more complete outcome reporting and follow-up. Therefore, a national well-designed prospective study and updated systematic review and meta analysis are needed to address these limitations and provide more standardized guidelines for managing pediatric GIB cases.

Conclusion

Our study, representing one of the largest reported pediatric GIB series to date, provides valuable insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of this emerging infection. Our findings reinforce the efficacy of voriconazole monotherapy while emphasizing the challenges associated with hepatic involvement. Notably, our results highlight that the early initiation of voriconazole therapy has significantly contributed to favorable outcomes and reduced the need for surgical intervention. This indicates the importance of prompt diagnosis and early antifungal treatment in mitigating disease severity. Although significant progress has been made in diagnosing and treating GIB, further studies are needed to refine treatment protocols, assess the role of PCR in diagnosis, and determine the most effective management strategies for refractory cases. Continued efforts to enhance early recognition and optimize therapeutic approaches are crucial in improving patient outcomes.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. Due to ethical restrictions, patient-level data cannot be publicly shared.

References

Acosta-España, J. D. & Voigt, K. An old confusion: entomophthoromycosis versus mucormycosis and their main differences. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1035100. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1035100 (2022).

Kwon-Chung, K. J. Taxonomy of Fungi causing mucormycosis and entomophthoramycosis (Zygomycosis) and nomenclature of the disease: molecular mycologic perspectives. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54 (Suppl 1), S8–S15. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cir864 (2012).

El-Shabrawi, M. H., Kamal, N. M., Kaerger, K. & Voigt, K. Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis: A Mini-Review. Mycoses 57 (Suppl 3), 138–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.12231 (2014).

Al Jarie, A. et al. Pediatr. Gastrointest. Basidiobolomycosis Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 22, 1007–1014, doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000095166.94823.11. (2003).

Shaikh, N. et al. A neglected tropical mycosis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 22, 688–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2016.04.005 (2016).

Vilela, R. & Mendoza, L. Human pathogenic Entomophthorales. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31 https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00014-18 (2018).

Geramizadeh, B., Heidari, M. & Shekarkhar, G. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis, a rare and under-Diagnosed fungal infection in immunocompetent hosts: A review Article. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 40, 90–97 (2015).

AlSaleem, K. et al. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis: mimicking crohn’s disease case report and review of the literature. Ann. Saudi Med. 33, 500–504. https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.2013.500 (2013).

Albaradi, B. A., Babiker, A. M. I. & Al-Qahtani, H. S. Successful treatment of Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis with voriconazole without surgical intervention. J. Trop. Pediatr. 60, 476–479. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmu047 (2014).

Juaid, A., Rezqi, A., Almansouri, W., Maghrabi, H. & Satti, M. Pediatric Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis: case report and review of literature. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 5, 167–171 (2017).

Almoosa, Z., Alsuhaibani, M., AlDandan, S. & Alshahrani, D. Pediatric Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis mimicking malignancy. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 18, 31–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mmcr.2017.08.002 (2017).

Al zaydani, S. M. .I.A. Case reports: Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in children. Curr. Pediatr. Res. 17, 1–6 (2013).

Saeed, M. A., Al Khuwaitir, T. S. & Attia, T. H. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis with hepatic dissemination: A case report. JMM Case Rep. 1, e003269. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmmcr.0.003269 (2014).

Saeed, A. et al. Ileocolonic basidiobolomycosis in a child: an unusual fungal infection. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 27, 508–510 (2017).

Hussein, M. R. et al. Histological and ultrastructural features of Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis. Mycol. Res. 111, 926–930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mycres.2007.06.009 (2007).

Sawan, A. & Mufti, S. T. Iman Rawas Basidiobolomycosis: A Case Report. Basidiobolomycosis: A Case Report October Egyptian journal of medicine 2010, 43, 25–30.

El-Shabrawi, M. H. F. et al. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis: an emerging fungal infection causing bowel perforation in a child. J. Med. Microbiol. 60, 1395–1402. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.028613-0 (2011).

Saadah, O. I., Farouq, M. F., Daajani, N. A., Kamal, J. S. & Ghanem, A. T. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in a child; an unusual fungal infection mimicking fistulising crohn’s disease. J. Crohns Colitis. 6, 368–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2011.10.008 (2012).

Ageel, H. I., Arishi, H. M. & Kamli, A. A. Aladdin Mahmoud hussein, Srinivas Bhavanarushi unusual presentation of Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in a 7-Year-Old child. Am. J. Med. Case Rep. 5, 131–134 (2017).

Saeed, A., Assiri, A. M., Bukhari, I. A. & Assiri, R. Antifungals in a case of basidiobolomycosis: role and limitations. BMJ Case Rep. 12, e230206. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2019-230206 (2019).

Al Asmi, M. M., Faqeehi, H. Y., Alshahrani, D. A. & Al-Hussaini, A. A. A case of pediatric Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis mimicking crohn`s disease. A review of pediatric literature. Saudi Med. J. 34, 1068–1072 (2013).

Albishri, A. et al. Gastrointest. Basidiobolomycosis J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 55, 101411, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsc.2020.101411. (2020).

Mohammed, M. et al. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in pediatric cases with Multiple-Site involvement: A case series. Cureus 16, e76451. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.76451 (2024).

Geramizadeh, B., Foroughi, R., Keshtkar-Jahromi, M., Malek-Hosseini, S. A. & Alborzi, A. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis, an emerging infection in the immunocompetent host: A report of 14 patients. J. Med. Microbiol. 61, 1770–1774. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.046839-0 (2012).

Arjmand, R., Karimi, A., Sanaei Dashti, A. & Kadivar, M. A child with intestinal basidiobolomycosis. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 37, 134–136 (2012).

Taghipour Zahir, S., Sharahjin, N. S. & Kargar, S. Basidiobolomycosis a mysterious fungal infection mimic small intestinal and colonic tumour with renal insufficiency and ominous outcome. BMJ Case Rep. bcr2013200244. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-200244 (2013).

Zabolinejad, N., Naseri, A., Davoudi, Y., Joudi, M. & Aelami, M. H. Colonic basidiobolomycosis in a child: report of a Culture-Proven case. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 22, 41–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2013.11.016 (2014).

Moghadam, A. G., Alborzi, A., Eilami, O., Bediee, P. & Gholam, R. Pouladfar zygomycosis in immunocompetent children in iran: case series and review. Scholars J. Appl. Med. Sci. (SJAMS). 3, 450–454 (2015).

Geramizadeh, B., Sanai Dashti, A., Kadivar, M. R. & Kord, S. Isolated hepatic basidiobolomycosis in a 2-Year-Old girl: the first case report. Hepat. Mon. 15, e30117. https://doi.org/10.5812/hepatmon.30117 (2015).

Sanaei Dashti, A. et al. Gastro-Intestinal basidiobolomycosis in a 2-Year-Old boy: dramatic response to potassium iodide. Paediatr. Int. Child. Health. 38, 150–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/20469047.2016.1186343 (2018).

Eghbalkhah, A., Habibi, M., Lesanpezeshki, M. & Shahinpour, S. Pediatric Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 8, 34–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pid.2016.03.008 (2016).

Fahimzad, A. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis as a rare etiology of bowel obstruction. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 36, 239–241 (2006).

Zekavat, O. R. et al. Colonic basidiobolomycosis with liver involvement masquerading as Gastrointestinal lymphoma: A case report and literature review. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 50, 712–714. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0057-2017 (2017).

de Aguiar, E., Moraes, W. C. & Londero, A. T. Gastrointestinal entomophthoramycosis caused by Basidiobolus Haptosporus. Mycopathologia 72, 101–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00493818 (1980).

Hassan, H. A. et al. Eosinophilic granulomatous Gastrointestinal and hepatic abscesses attributable to basidiobolomycosis and fasciolias: A simultaneous emergence in Iraqi Kurdistan. BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-91 (2013).

Bittencourt, A. L., Ayala, M. A. R. & Ramos, E. A. G. A new form of abdominal zygomycosis different from mucormycosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 28, 564–569. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.1979.28.564 (1979).

Al-Maani, A. S. et al. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis: first case report from Oman and literature review. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 14, e241–e244 (2014).

Edington, G. M. Phycomycosis in ibadan, Western nigeria. Two postmortem reports. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 58, 242–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/0035-9203(64)90036-7 (1967).

Mandhan, P., Hassan, K. O., Samaan, S. M. & Ali, M. J. Visceral basidiobolomycosis: an overlooked infection in immunocompetent children. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg. 12, 193–196. https://doi.org/10.4103/0189-6725.170218 (2015).

Gómez-Muñoz, M. T., Fernández-Barredo, S., Martínez-Díaz, R. A., Pérez-Gracia, M. T. & Ponce-Gordo, F. Development of a specific polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of Basidiobolus. Mycologia 104, 585–591. https://doi.org/10.3852/10-271 (2012).

Ghazwani, S. M. et al. Pediatric Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis: A retrospective study from Jazan province, Saudi Arabia. Infect. Drug Resist. 16, 4667–4676. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S416213 (2023).

Sehrawat, R., Bansal, N., Srivastava, A., Malik, D. & Vij, V. Hepatic basidiobolomycosis masquerading as cholangiocarcinoma: A case report and literature review. J. Liver Canc. 23, 389–396. https://doi.org/10.17998/jlc.2023.06.07 (2023).

Al-Shanafey, S., AlRobean, F. & Bin Hussain, I. Surgical management of Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in pediatric patients. J. Pediatr. Surg. 47, 949–951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.01.053 (2012).

Rose, S. R. et al. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis treated with posaconazole. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2, 11–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mmcr.2012.11.001 (2012).

Jafarpour, Z., Pouladfar, G., Dehghan, A., Anbardar, M. H. & Foroutan, H. R. Case report: Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis with Multi-Organ involvement presented with intussusception. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 105, 1222–1226. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-1387 (2021).

Ateik, A. et al. Hepatic basidiobolomycosis in a 2-Year-Old child: A case report. J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 102956 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsc.2025.102956 (2025).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Nabil S. Dhayhi, Alanoud Zaid Aljarbou, Ibrahim Zaid BinHussain, Methodology: Nabil S. Dhayhi, Abdulaziz H. Alhazmi, Haider M. Arishi, Ibrahim Zaid BinHussain, Data Collection: Nabil S. Dhayhi, Alanoud Zaid Aljarbou, Abdullah Ahmed Yatimi, Rehab Abdalrhman Humedi, Salman Ghazwani, Madani Essa, Abdulaziz Mohammed Safhi, Mohammed Ahmed Alameer, Hanan Mothaqab Mashi, Hanin Muflih Althamer, Abdullah Hassan Alhamoud, Mousa Mobaraki, Abdulrahman Abdullah Muhajir, Abdulmalik Abdullah Najmi, Asim Ali Bakri. Data Analysis & Interpretation: Abdulaziz H. Alhazmi, Writing – Original Draft: Nabil S. Dhayhi, Alanoud Zaid Aljarbou, Abdulaziz H. Alhazmi, Writing – Review & Editing: Nabil S. Dhayhi, Abdulaziz H. Alhazmi, Ibrahim Zaid BinHussain, Supervision: Ibrahim Zaid BinHussain.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was waived for this study by the Institutional Review Board of Jazan Health Ethics Committee and King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (KFSHRC) Research Ethics Committee, due to the retrospective nature of the study, and because the data were anonymized and posed minimal risk to participants.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dhayhi, N.S., Aljarbou, A.Z., Alhazmi, A.H. et al. Pediatric gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis: descriptive bicenteric retrospective study. Sci Rep 15, 27211 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13098-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13098-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Liposomal amphotericin B in the treatment of pediatric gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis

Journal of Medical Case Reports (2026)