Abstract

Efficient space heating is vital for sustainable building design, offering opportunities to reduce energy consumption and costs while maintaining thermal comfort. This study examines the optimization of space heating in a nearly-zero energy building (nZEB) located in Oslo, Norway, under cold climatic conditions. The research question explores how advanced control strategies can balance heating costs and thermal comfort efficiently. A novel Model Predictive Control (MPC) framework integrates Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural networks for energy demand prediction and the Ant Nesting Algorithm (ANA) for multi-objective optimization. Dynamic predictions for indoor temperature and heating requirements, based on EnergyPlus simulations and real weather data, guide the system in minimizing heating costs (HC) and comfort penalties (CP) simultaneously. The MPC framework incorporates constraints aligned with ASHRAE Standard 55 adaptive comfort theory, ensuring efficient control of temperature setpoints between 20 °C and 22 °C. Pareto set analysis evaluates optimization outcomes for selected winter days and electricity price scenarios ($0.328/kWh vs. $0.493/kWh), with results demonstrating up to 17% daily heating cost savings compared to conventional methods while maintaining comparable thermal comfort levels. The implications of the research indicate that the suggested framework has the potential to be integrated into automated systems for real-time predictive control, offering a promising tool for building managers and designers. While the proposed framework shows potential as a valuable approach to sustainable heating optimization, it represents one of several methods that can contribute to improving energy efficiency and comfort in sustainable building design, particularly in nearly-zero energy buildings located in cold climates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The construction sector assumes a crucial function in the worldwide energy consumption and emissions, whereby structures contribute to 8% of emissions in a direct manner via the production of building services applied in structures1. The IEA has reported that the building industry must take steps to decrease its environmental footprint2. The escalated levels of energy consumption and emissions observed in 2021 can be primarily ascribed to the resurgence of economic activity subsequent to the lifting of COVID-19 constraints. As industrial and commercial activities intensify, the need for energy concurrently surges, leading to elevated emissions3.

The achievement of zero-carbon buildings necessitates substantial investments in renewable energy, energy-efficient technologies, and building retrofits, presenting potential for the emergence of fresh employment prospects and the instigation of economic growth4. In order to attain the objective of constructing buildings with zero carbon emissions by the year 2030, it is imperative that policymakers, proprietors of buildings, and prominent leaders in the industry cooperate with one another to design inventive financing mechanisms, simplify regulatory procedures, and enhance public cognizance and involvement5.

Advanced HVAC control systems have the potential to enhance several aspects of buildings aside from energy savings and greenhouse gas emissions reductions. Indoor air quality, occupant comfort, and productivity can all be positively impacted by these systems6. Sophisticated HVAC control mechanisms may comprise characteristics including occupancy sensors, meteorological forecasting, and machine learning algorithms to enhance energy utilization predicated on the building’s occupancy, atmospheric conditions, and other determinants7. The EU policy encompasses not only the establishment of automation and control systems for buildings but also the stipulation of prerequisites for insulation of the building envelope, efficient illumination, and renewable energy systems8. These requirements aim to improve the energy efficiency of structures9.

The integration of advanced control methodologies, such as data analytics and artificial intelligence—including its subset, machine learning—is becoming increasingly prevalent in building management systems10. This integration is aimed at improving energy efficiency, enhancing occupant comfort, and optimizing operational performance11. The implementation of model predictive control (MPC) in building systems necessitates the amalgamation of diverse sensors, data analytics, and control algorithms to establish precise models of building behavior and refine energy consumption12. MPC has the capability to facilitate the assimilation of sustainable energy sources, energy storing mechanisms, and electric automobiles with an aim to supply the grid with flexible services and bolster the move towards a more sustainable energy system. The construction of reliable MPC models demands precise data concerning building conduct, energy consumption, and resident habits, which can be procured via several sensing technologies, Internet of Things (IoT) devices, and data analysis tools13.

One of the predicaments in the deployment of sophisticated control methods in building systems is the dearth of standardized building and HVAC system configurations, which engenders a formidable obstacle in developing all-encompassing control strategies that can be efficaciously implemented across various edifices14. The implementation of sophisticated control techniques in building systems necessitates collaborative efforts among various stakeholders, namely building proprietors, designers, engineers, and contractors, to guarantee that control strategies are designed, executed, and sustained in a proficient manner15. The implementation of uniform building performance metrics and benchmarking tools can effectively facilitate the integration of sophisticated control techniques into building systems by permitting more precise evaluations of building performance and recognition of potential areas for enhancement16.

Achieving optimal management and action of HVAC systems is crucial for reducing energy consumption in buildings while maintaining comfortable indoor temperatures17. The commonly used control strategies, such as on/off and proportional-integral-derivatives, lack the sophistication to consider edifice dynamics and are often linked with low effectiveness. More advanced and dynamic control strategies are required to optimize building performance18.

Related work

Model Predictive Control (MPC) has emerged as a promising solution to improve energy efficiency and thermal comfort in building energy management systems. While establishing accurate controller models is integral to MPC’s effectiveness, challenges remain in optimizing building performance due to the complexity of nonlinear and discontinuous processes. To address these challenges, researchers have explored three primary modeling paradigms: white-box, grey-box, and black-box models, each offering distinct trade-offs in terms of precision, computational efficiency, and practical applicability.

White-box models are rooted in fundamental physical principles, providing detailed descriptions of building dynamics using the technical specifications of structures. Despite their accuracy, white-box models often require substantial computational resources and time, limiting their practicality in real-time MPC applications. Grey-box models combine empirical data with simplified physical relationships, enabling reduced complexity while maintaining adequate accuracy. This balance makes grey-box models a versatile option for many MPC implementations. Black-box models, relying solely on empirical data, offer cost-effective solutions with flexible input-output dynamics but are limited by the need for extensive training datasets and potential inaccuracy outside training ranges19,20,21. Below are some studies about the application of MPC in energy consumption optimization:

Lee et al.22 conducted a study to verify the effectiveness of employing an MPC-based approach for energy systems in commercial buildings, while considering fluctuations in occupancy rates and temporal fluctuations in electricity costs. They conducted a comparison between the MPC approach and a conventional Rule-Based Control (RBC) strategy. Utilizing artificial neural network prediction models and a metaheuristics algorithm, an MPC controller that is both dependable and computationally was constructed. This controller was utilized to determine optimal operations for the chiller and storage system in order to minimize operating costs and maintain the cooling set point temperature during operation hours. During a four-day simulation, Lee et al. discovered that the MPC approach, utilizing a 24-hour prediction horizon and a 1-hour control intervals, resulted in a 3.4% reduction in operating costs, compared to a traditional RBC strategy, which prioritized managing the thermal load by operating the storage system. The findings of the study indicate that deploying MPC can significantly enhance the operating efficiency of commercial building energy systems, especially when responding to changes in occupancy levels and fluctuating electricity rates.

Du et al.23 have conceived a model of regulation for expansive, multi-regional structures that aims to enhance energy efficiency without compromising thermal comfort. They devised a paradigm to flexibly regulate the temperature set point in distinct areas in accordance with demand intensity, with the overarching objective of judiciously curtailing load. With the aid of a sophisticated optimization strategy, they achieved precise parameter values for the system level. At the lower regulatory level, the optimized variables were effectively handled through implementation of MPC, renowned for its swift response time. The researchers discovered that the dynamic modification of the temperature set point during a standard day can result in a 6.16% decrease in load demand, while still ensuring the optimal comfort of individuals occupying indoor spaces. Through the simulation of operational optimization and MPC strategy, which is based on load demand optimization, a significant total energy savings of 12.78% was achieved for the HVAC system. This study presented a highly effective intelligent regulation plan for boosting energy efficiency in multi-region buildings, that is relies on multi-criteria optimization and MPC. This approach was capable of meeting the occupants’ refined requirements for quality of life.

Carli et al.24 developed a MPC algorithm for the purpose of enhancing energy efficiency and indoor thermal comfort within building energy management systems. They forecasted the building’s energy performance using Fanger’s Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) as a thermal comfort measure and a simplified thermal model. By integrating the Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) index and a factor for energy conservation in the cost function, the MPC method successfully answers a manageable and sophisticated non-linear optimization problem, enabling the choice of the best control actions. They used the MPC methodology to an office building’s building automation system at the prestigious Polytechnic of Bari in Italy. In contrast to a traditional thermal comfort management strategy that relies on thermostats, they also conducted a number of on-site experiments to thoroughly assess the algorithm’s effectiveness in real-world situations. The study highlighted the possibility of using MPC within energy management systems for buildings to decrease energy consumption while maintaining thermal comfort.

Yang et al.25 introduced an event-triggered mechanism (ETM) to mitigate the significant computational demands of MPC for the management of building energy. In contrast to the time-triggered mechanism (TTM) employed by MPC, which performs optimization iteratively at every time step, the suggested ETM exclusively initiates optimization when triggering events come to pass, depending on a cost function that encompasses past, present, and future data. They developed an event-triggered MPC (ETMPC) system based on machine learning to improve building energy efficiency and thermal comfort. The air-conditioning control performance of the ETMPC system was examined using simulations and compared to that of an MPC using TTM and a common thermostat. The suggested ETMPC decreased the computational burden by 77.6%−88.2% in comparison to the MPC using TTM, while yielding comparable energy savings. The ETMPC delivered equivalent thermal comfort result to the MPC using TTM while surpassing the thermostat substantially. The study demonstrated that the proposed ETMPC system may achieve comparable energy savings and thermal comfort performance as the traditional TTM-based MPC while reducing computational burden.

While MPC shows promise for optimizing energy efficiency and thermal comfort in buildings, there’s a need for more practical and scalable implementations. Current MPC approaches face challenges related to model complexity, computational burden, and the requirement for extensive training data, especially when dealing with nonlinear and discontinuous building processes. Although studies have demonstrated the benefits of MPC in specific scenarios, further research is required to address the limitations of each modeling approach (white-box, grey-box, and black-box) and to develop MPC strategies that can be easily integrated into existing building automation systems while maintaining accuracy and robustness across various building types and operational conditions. Specifically, there’s a lack of research focusing on:

-

Developing hybrid modeling approaches that combine the strengths of different model types to achieve a better trade-off between accuracy, computational efficiency, and data requirements.

-

Creating adaptive MPC strategies that can automatically adjust model parameters and control actions based on real-time data and changing building conditions.

-

Investigating the long-term performance and cost-effectiveness of MPC implementations in real-world buildings, considering factors such as sensor accuracy, data quality, and system maintenance.

-

Addressing the scalability of MPC for large-scale deployment in diverse building portfolios, including the development of standardized MPC frameworks and tools.

-

The interpretability of MPC models, particularly for black-box and grey-box approaches, to ensure transparency and facilitate trust in the control system’s decision-making process.

The authors previously investigated MPC for HVAC systems and presented a conceptual model for simulation-based MPC that maximizes energy efficiency and thermal comfort. They also looked at employing of ANNs in conjunction with MPC. In this study the goals contain to demonstrate the dependability of ANNs, specifically LSTM networks, using EnergyPlus simulation software, as well as to show that ANNs may save computing time when compared to standard simulation methods. This study also show how MPC for space heating may save energy and money while improving thermal comfort when compared to a traditional control technique. The article introduces and assesses an MPC framework for space heating systems that leverages ANNs to fill research gaps in this sector.

Case study

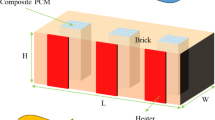

The office building case study in this research is located in Oslo, Norway, a city characterized by a cold and temperate climate that presents substantial heating demand. To contextualize the climatic conditions and their impact on building energy consumption for space heating systems, Table 1 provides the average monthly temperatures for Oslo, based on historical climate data26. The building is a recently erected office building encompassing a net conditioned expanse of approximately 200 m2, situated in the urban center. The structure is purposed to be a nearly-zero energy building, replete with an array of instruments, detectors, and effectors for gauging both interior and exterior meteorological circumstances, as well as the power usage of all installed equipment, and renewable energy sourcing systems.

The building is designed with a well-insulated envelope, which has a thermal transmittance (U) of 0.15 W/m2K for the exterior walls, 0.18 W/m2K for the ceiling, 0.03 W/m2K for the foundation floor, and 0.7 W/m2K for the internal partitions. The building also boasts a high-performance HVAC mechanism that features a nominal cooling/heating potential of 100 kW and a heating operation performance coefficient of 4.0. Moreover, said building is outfitted with a geothermal heat pump system that effectively employs vertical boreholes, reaching a depth of 150 m, to furnish supplementary heating and cooling.

The objective of the study is to optimize the building’s heating operation through the utilization of MPC to curtail energy consumption while simultaneously ensuring occupant comfort. The MPC mechanism will be empowered by ant nesting algorithm (ANA) and LSTM neural networks to anticipate the heating requirement of the building founded on both indoor and outdoor climatic factors, and regulate the heating system’s operation accordingly. The study will calibrate and validate the building’s energy simulation model using monitored data and assess the replicability of the study in real conditions. The study will calibrate and validate the energy model of the building using monitored data and assess the feasibility of applying the findings in actual circumstances. The building’s energy model was created using Design Builder® software27 and was then exported to Energy Plus28 to execute the MPC approach. The model was adjusted and confirmed using recorded information in a previous study29.

Overall, this particular case study shall exhibit the efficacy of MPC in the optimization of energy utilization for nearly-zero energy edifices situated in frigid climatic conditions, thereby highlighting the possibility of considerable savings in energy and cost.

Research methodology

Artificial neural network and LSTM method

Simulation software such as Design Builder®/Energy Plus, IDA ICE, TRNSYS®, and ESP-r have demonstrated proficiency in accurately predicting energy consumption and comfort levels in buildings. Nonetheless, achieving the desired level of reliability and precision in these simulations frequently necessitates substantial computational resources. To surmount this challenge, an artificial intelligence system is developed that leverages machine learning algorithms, including artificial neural networks, to assess the energy efficiency of buildings with exceptional accuracy and computational efficiency. ANNs are regarded as a “black box” that creates an output depending on one or more input variables. ANNs possess a remarkable strength in modeling intricate correlations among output and input variables, which can be challenging to express using conventional analytical functions. For training an ANN, a straightforward phenomenological model is typically necessary. During the training phase, by selecting appropriate input variables and utilizing the output data obtained from the physical model under consideration, ANNs can learn to model the intricate connections between these variables. Once trained, ANNs can effectively predict the results of additional external input values that were not part of the training data. In the present article, the EnergyPlus determined building energy balance is employed as the fundamental physical model for the research. The MATLAB® software is utilized to fashion the artificial neural networks. Through the utilization of ANNs for assessing building energy output, noteworthy precision levels are attained while considerably diminishing the computational resources essential. This methodology possesses the potential to ameliorate the efficacy and sustainability of building energy administration and optimization.

A prominent type of recurrent neural network, an LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) network, is chosen for its remarkable ability in forecasting building energy demands30. The LSTM, while lacking explicit exogenous inputs, has the ability to implicitly learn and incorporate them through its input gate. The LSTM’s architecture comprises a cell state, input gate, forget gate, and output gate. The LSTM is trained using a sequence-to-sequence architecture to simulate a dynamic system.

In brief, the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) cell accepts the present input, prior internal state, and gate activations to revise its internal state and yield a hidden state at each time interval. The produced hidden states are subsequently conveyed through one or more fully connected layers to create the output sequence, retaining the original semantic content. To train the LSTM model, a sequence-to-sequence architecture is utilized to forecast the next value of the output signal, taking into account its past outputs and inputs. The primary aim of the training process is to reduce the mean squared error between the predicted output sequence and the actual output sequence on the training data set. There is no single defining equation for the LSTM model, but rather is trained using a sequence-to-sequence architecture and backpropagation through time to learn to model complex temporal dependencies in sequential data.

The prime purpose of the neural network, notably the LSTM model in this case, is to forecast the indoor temperature and the amount of thermal power necessitated during the entire year. To anticipate diverse operational situations, several LSTM networks are instituted:

-

A LSTM network is employed to forecast the temperature of the indoor air measured using a dry bulb thermometer on an hourly basis (\(\:{T}_{i}\)) as the resultant variable.

To forecast the hourly heating requirement (HR) for a nearly zero-energy building (nZEB), a single LSTM network was used instead of employing separate models for fixed setpoint temperatures. This approach ensures the model can handle dynamic changes in setpoint temperatures rather than being limited to fixed values. The selected setpoints (20 °C, 21 °C, and 22 °C) are representative of practical operational ranges: temperatures below 20 °C may cause discomfort, while those above 22 °C may be too warm for occupational environments.

Considering the building’s thermal mass, which stores and releases heat depending on setpoint variations, the model’s inputs are designed to account for these dynamics. Key inputs include indoor and outdoor air temperatures, past heating requirements (up to one hour prior), dynamic changes in setpoints, and relevant time-dependent features. This input configuration allows the LSTM network to capture how the thermal mass affects heating demand under varying setpoint conditions. To further enhance performance and minimize the comfort penalty (CP), a fitness function was employed during the optimization process. This function ensures that heating demand forecasts align with dynamic setpoint variations while maintaining occupant comfort and optimizing system performance:

-

1.

The solar radiation rate on a global scale per unit area of the specific location during the predicted hour is measured (\(\:wh/{m}^{2}\));

-

2.

The temperature of the dry-bulb air outdoors at the predicted hour in the given location (°C);

-

3.

The temperature of the “indoor dry-bulb air one hour before the” expected time (°C);

The performance of a building is influenced by various factors beyond those considered in simulations. To evaluate the effectiveness of the network, occupancy and lighting inputs are assumed to be zero. However, this approach is a significant limitation for administrative buildings as it overlooks the impact of internal dynamics beyond inhabitant control. Accurate estimation of the number of individuals or at least the average is critical for precise performance evaluations since occupancy is a substantial contributor to office building performance. Having a precise record of the building’s occupancy on an hourly basis is crucial to consider the internal heat generation and, consequently, to obtain a more accurate estimate of the heating requirement. The applicability and replicability of the model in various climates is subject to a significant limitation. The reliability of the network’s predictions is heavily dependent on the training dataset and is susceptible to the effects of the climate it represents31. This phenomenon has been observed by some of the authors, illustrating the necessity of closely aligning the prediction with the climate of the dataset to secure accuracy.

The first step in the development of the LSTM model for the purpose of training artificial neural networks entails the importation of both input and output data that has been generated by EnergyPlus simulations into the MATLAB® platform. To achieve maximum adaptability, numerous operational schedules are utilized during the training of LSTM networks. To produce a complete a comprehensive dataset that encompasses various scenarios of system activation and deactivation, the dataset encompasses the “turning on and off of the system under dissimilar circumstances. The dataset of analyzed scenarios comprises of 59 days or 1416 hours, including the system operating in continuous operation, intermittent operation with a one-hour interval, intermittent operation with a two-hour interval, intermittent operation with a three-hour interval, and intermittent operation with a four-hour interval. These scenarios are considered for a 2-month duration, from March 1 to April 30, for each hour of the year, resulting in a total of 7200 data points. The dataset is created to account for various system operation scenarios and their impact on the energy performance of the building. The selected file containing climate data has been obtained from the source of IWEC32. The dataset in question is focused on the urban center of Oslo.

To determine the exact configuration of each artificial neural network, a heuristic methodology is implemented, which engenders manifold values for hyperparameter nodes in the hidden layer, input delays, and feedback delays. The training of all neural networks is done using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm, and the mean square error is utilized to gauge the quality of the neural network produced.

Since the initial weight and bias configurations and the partitioning of data into training, validation, and testing subsets can vary, a distinct outcome may be obtained whenever a neural network is trained. Consequently, multiple neural networks trained on the same problem may yield diverse results from the identical input. To guarantee the establishment of a neural network with utmost precision, it is indispensable to undertake iterative training. The maximum number of iterations, known as epochs, is fixed at 250,000. In addition, a threshold of \(\:{10}^{-9}\) for the gradient is embraced as a supplementary halting condition during the construction of the network, signifying the squared error function.

The created LSTM networks’ performance is measured using two metrics: root mean squared error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE). These measures serve as indicators of the precision of predictions and the degree of discrepancy from the factual values. Ascertaining the fit between predicted and observed values by a neural network is often evaluated through the utilization of the RMSE metric. The MAE, on the other hand, is a linear metric that gives equal weight to each individual variation from the mean, whereas the RMSE is a quadratic scoring method that assesses the typical magnitude of the error. Equations (1) and (2) illustrate how to compute these measures:

Given a sample size of \(\:n\), the predicted value is represented by \(\:{z}_{i}\) and the factual value is represented by \(\:z\).

The computation of the root mean squared error (RMSE) involves the squaring of the discrepancies between the foretold and factual values. As such, the RMSE exhibits a greater degree of sensitivity to atypical observations than the mean absolute error (MAE), thereby imposing more severe punishment on larger errors than on smaller ones. Concomitantly, it is worth noting that the influence of outliers on the RMSE value exceeds that on the MAE value.

To address the training and evaluation of the employed LSTM networks, this study relied on energy consumption datasets generated through EnergyPlus simulations. The following steps outline the methodology for data collection and preprocessing:

1. Data Collection:

The training dataset was based on EnergyPlus simulations coupled with Oslo’s climate data obtained from the IWEC database. This dataset includes hourly features, such as indoor and outdoor air temperatures, past heating demands, dynamic setpoint changes, and solar radiation levels. The simulated dataset encompasses diverse operational schedules, including both continuous and intermittent operation scenarios over a two-month period (March and April), resulting in 7,200 data points covering various system status configurations.

2. Preprocessing steps:

-

a.

Data Cleaning: The dataset was examined to identify and handle missing values or outliers. This involved excluding invalid entries and ensuring consistent time sequences for hourly prediction tasks.

-

b.

Normalization: To improve model convergence and prediction accuracy, all input features were normalized to a scale of 0–1, which mitigates the impact of varying magnitudes across input variables.

-

c.

Partitioning: The dataset was divided into training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%) subsets to ensure robust model evaluation and prevent overfitting. These partitions were randomized to avoid introducing temporal biases.

3. Feature Engineering

Key features included: outdoor temperature, which significantly impacts heating demand, indoor air temperature and heating requirements from the previous hour, capturing temporal dependencies, and solar radiation and dynamic setpoint changes, which influence building thermal conditions and control strategies. These features were selected to align with the physical characteristics of the building’s thermal mass and its interactive effects with weather conditions and occupancy schedules.

4. Data Augmentation:

While the study mainly relied on simulation-based data, future work may explore incorporating data augmentation techniques such as variations in weather profiles or HVAC system configurations to improve generalization and adaptability across climates and building types.

The current framework has certain limitations associated with its dependence on datasets specific to nearly-zero energy buildings (nZEBs) in Oslo. To improve its generalization capability across diverse climates and building configurations:

-

Future research should incorporate datasets from varying climatic conditions, diverse HVAC system setups, and different building types.

-

Feature selection methods, such as correlation analysis or principal component analysis (PCA), could be applied to optimize input variables for capturing complex interactions in varying scenarios.

Ant nesting algorithm optimizer

This section elucidates a comprehensive account of the Ant Nesting Algorithm (ANA) simulation is presented.

Entities

Leptothorax ants use an artificial searching process to build new nests, in which worker ants act as agents. In all circumstances, laborers deposit grains in the vicinity of the queen, wherein the finest position for grain placement, among all probable locales, embodies the global optimal outcome. The ANA optimization methodology posits that the fitness function is constituted by the influence of the deposition context on the wall association and proximity to other stones. Every laborer possesses a stochastic deposition weight, denoted as \(\:{d}_{w}\), which determines their selection of the deposition location based on the cost and outcome metrics of previous and present deposition scenarios. The ANA optimizer regards workers as agents of search, deposition situation as a potential outcome, fitness function as a specification of the deposition situation, deposition weight as a decision-making element of the workers, optimal result as the most favorable deposition location, and previous deposition situation as either a nestmate or a stationary stone.

The ANA optimization method integrates the existence of nestmates or immobile stones that foraging ants may come across during their search for appropriate sites to deposit grains in the nest. To simulate this phenomenon, the antecedent scenario \(\:{Y}_{t,former}\) of the laborer is employed, signifying the immovable rock or conspecific encountered by the laborer in the course of the optimization procedure. The antecedent deposition locality of the laborer mirrors the immobile stone or nestmate encountered.

Modeling with mathematics

The algorithm proposed in this study draws inspiration from the nesting process of worker ants. In order to locate suitable destinations for grain deposition, the algorithm emulates the workers’ exploration of various potential outcomes. Through the selection of the most favorable outcome from several viable alternatives, the optimal deposition location is determined, emulating the ants’ capacity to converge towards the optimal result.

In nature, the worker ants engage in the collection of grains as well as the search for suitable sites for deposition. They simultaneously construct a protective wall around the queen’s nest. However, the optimization method presented in this study models only a single cycle of grain dropping. This simulation is aimed at capturing the workers’ quest for a single deposition site during the nesting process. It is noteworthy that the algorithm does not take into account the initial construction workers who rely on brood collection to determine the location of the nesting wall. Furthermore, the simulation algorithm assumes that the initial depositions have been completed before the grain dropping process.

In the proposed methodology, a group of artificial workers is randomly allocated within the solution area \(\:{Y}_{i}\) (where \(\:i\) ranges from 1 to n). These workers engage in a process of exploration, seeking out new deposition scenarios and conducting random searches for superior options. In the event that an improved deposition scenario is discovered, it is adopted as the optimal outcome. However, in situations where the new outcome is inferior to the current one, the algorithm persists in its search until the present outcome is deemed the most favorable option for that specific point.

This study presents a novel approach that replicates the stochastic search behavior of wildlife workers when identifying potential deposition sites. The proposed technique involves individuals exploring the landscape randomly, with the inclusion of a deposition weight factor. At each time step, an individual is endowed with a new deposition scenario \(\:{Y}_{t+1,i}\) (where \(\:i=\:[1,\:n]\) and \(\:t=[1,\:m]\), and \(\:n\) and \(\:m\) represent the number of swarm and repetition) by adding the alteration ratio of the deposition scenario (\(\:{\varDelta\:Y}_{t+1,i}\)) to their current deposition scenario \(\:{Y}_{t,i}\). The formula outlined in the study can be leveraged to update the deposition scenario of individuals within the swarm:

The symbols \(\:t\) and \(\:i\) are utilized to denote the present iteration and the laborer, while \(\:Y\) and \(\:{\varDelta\:Y}_{t+1,i}\) are employed to respectively signify the current deposition condition of individuals and the alteration in their deposition condition.

The value of \(\:{\varDelta\:Y}_{t+1,i}\) is influenced by two factors: the weight of the deposition (\(\:{d}_{w}\)) and the difference between the deposition status of the best-performing local individual (\(\:{Y}_{t,i,finset}\)) and the current individual’s deposition status (\(\:{Y}_{t,i}\)). This difference is calculated using a mathematical model that simulates a leaning process towards the lowest point of the construction material. As a result, each individual has a natural inclination to improve its deposition status and move towards the best-performing individual, which represents the optimal outcome. Therefore, the following formula can be used to calculate \(\:{\varDelta\:Y}_{t+1,i}\):

Whenever the current individual has been the highest performing one, the following principles have been applied to calculate the value of \(\:{\varDelta\:Y}_{t+1,i}\):

The present state of deposition is identical to the prior state:

Here \(\:R\) represents a randomly generated value ranging from − 1 to 1.

The determination of \(\:{d}_{w}\) is predicated upon the utilization of a mathematical simulation that takes into consideration the stochastic movements of laborers. This simulation factors in both their current and prior predilections for deposition (\(\:{T}_{r}\) and \(\:{T}_{r,\:prior}\)) with respect to a given grain scenario. These tendencies are calculated using the Pythagorean formula, where \(\:{T}_{r}\) and \(\:{T}_{r,\:prior}\) represent the sides of the slope between the present and prior deposition status of an individual and the best-performing deposition status discovered so far, with the fitness difference between them as the other side. The calculation method for \(\:{T}_{r}\) and \(\:{T}_{r,\:prior}\) is based on the computation for a single worker. Therefore, to minimize the fitness, the value of \(\:{d}_{w}\) can be determined as follows:

As previously stated, \(\:R\) denotes a random amount that spans from − 1 to 1 and is implemented as a parameter to control \(\:{d}_{w}\). The Levy flight technique is utilized to generate stochastic values, owing to its uniform distribution curve that leads to more consistent movements.

The following equations have been employed to compute the present and prior deposition tendencies of the worker (\(\:{T}_{r}\)and \(\:{T}_{r,\:prior}\)):

Where, \(\:{Y}_{t,i,\:prior}\) denotes the prior deposition status of the worker. \(\:{fitness\:Y}_{t,i}\), \(\:fitness\:{Y}_{t,i,finset}\), and \(\:{fitness\:Y}_{t,i,prior}\) indicate the fitness function amount of deposition situation for the present, the finest, and prior worker.

Mechanism of working

The methodology commences by randomly assigning deposition statuses, \(\:{Y}_{t,i}\) (i = [1, n], t = [1, m]), to each member of the swarm within the lower and upper limits. Initially, the prior deposition status, \(\:{Y}_{t,i,\:prior}\), is set equal to \(\:{Y}_{t,i}\) for every individual, as they are all part of the 1 st generation. Subsequently, for each iteration, the global best deposition status, \(\:{Y}_{t,i,finset}\), is identified, a random value, R, is generated from − 1 to 1, and a comparison is made between \(\:{Y}_{t,i}\) and \(\:{Y}_{t,i,finset}\) for each member of the swarm. If the present worker’s deposition status is equivalent to the global finest result, \(\:{Y}_{t,i}={Y}_{t,i,finset}\), then \(\:{\varDelta\:Y}_{t+1,i}=R\times\:({Y}_{t,i}\)). Conversely, if the prior deposition status is identical to the present one, then \(\:{\varDelta\:Y}_{t+1,i}=R\times\:({Y}_{t,i,finset}-{Y}_{t,i}\)). Otherwise, \(\:{T}_{r}\), \(\:{T}_{r,prior}\), \(\:{d}_{w}\), and \(\:{\varDelta\:Y}_{t+1,i}\) are calculated utilizing the aforementioned formulas.

Using the first equation presented in this section, a novel outcome, \(\:{Y}_{t+1,i}\), is obtained. Once a novel outcome is obtained by the individuals, a fitness function is applied to determine if the novel status is an improvement over the present one. If the novel status is better, it replaces the present status, and the prior status is stored as \(\:{Y}_{t,i,\:prior}\). However, if the novel status is not an improvement, the present status is retained until the next iteration.

In order to apply the optimization method for maximizing issues, two modifications need to be made to the formula. Firstly, \(\:{d}_{w}\) should be computed utilizing the following equation:

The second modification involves changing the condition used to select the finest outcome.

-

Introduction to MPC

MPC is an advanced, data-driven control strategy that optimizes system performance by predicting future behavior and making adjustments accordingly. In the context of this study, the MPC framework leverages the ANA and LSTM-based predictive models to improve building energy efficiency and occupant comfort. Below is an overview of the key components of MPC and their roles in this research:

-

(i)

Objective Function:

MPC employs two competing fitness functions in this study: the Comfort Penalty (CP), which quantifies deviations from desired indoor temperatures, and the Heating Cost (HC), which reflects the monetary cost of operating the heating system. These functions are minimized simultaneously to balance thermal comfort and economic efficiency, forming the foundation of the optimization problem.

-

(ii)

Prediction Horizon:

The prediction horizon determines the time frame within which future system behavior is forecasted and optimized. In this research, the prediction horizon spans 24 h to account for daily variations in weather, occupancy, and energy demand. This ensures the system dynamically adapts the setpoint temperatures to minimize energy usage while maintaining acceptable comfort levels.

-

(iii)

Constraints:

Constraints in the optimization problem ensure that heating system operations remain within feasible limits while satisfying thermal comfort requirements. For example, setpoint temperatures are constrained to lie within 20 °C to 22 °C to maintain comfort while minimizing energy usage. Additionally, ASHRAE Standard 55 is used to incorporate adaptive thermal comfort constraints based on indoor environmental changes.

-

(iv)

Time Step:

The time step refers to the intervals at which decisions are computed and implemented. For this work, an hourly time step is used, synchronizing the control decisions with hourly weather forecasts, occupancy schedules, and building dynamics.

-

(v)

Optimization Algorithm:

The ANA is used to solve the multi-objective optimization problem. ANA mimics the foraging behavior of ants to iteratively search for the optimal combination of setpoint temperatures that minimize both CP and HC fitness functions. Its stochastic approach ensures robust convergence even for nonlinear, dynamic systems like building HVAC operations.

The adoption of MPC in this study showcases its ability to integrate predictive modeling (via LSTM networks) and optimization (via ANA) to achieve high-efficiency building management solutions under realistic operating conditions.

-

Justification for Choosing ANA.

The ANA was selected for this study due to its inherent ability to perform multi-objective optimization while maintaining computational simplicity and efficiency. While more commonly used optimization methods, such as Genetic Algorithm (GA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), have demonstrated reliability in various domains, ANA offers unique advantages that align with the specific requirements of this research:

-

I.

Reduced Computational Complexity:

ANA simulates ant behavior through stochastic iteration and deposition modeling, enabling faster convergence towards optimal solutions compared to GA and PSO, which often require extensive population evaluation or complex evolutionary mechanisms.

-

II.

Adaptability to Dynamic Systems:

The problem of optimizing heating consumption and comfort penalty involves frequent adjustments to external conditions such as weather and occupancy. ANA’s flexible deposition mechanism is well-suited for adapting to such dynamic systems, where other algorithms may require additional tuning or reconfiguration.

-

III.

Scalability:

ANA’s lightweight computational framework allows it to scale efficiently for larger optimization problems without significantly increasing computational demand, compared to GA and PSO, which can struggle with scalability due to larger population sizes and more complex fitness functions.

-

IV.

Unique fitness function design:

ANA employs a fitness function inspired by natural behavior patterns, encapsulating deposition weights and proximity evaluations. This design uniquely aligns with the heating optimization problem, enabling better trade-off management between heating costs and comfort penalty.

While the study focused on demonstrating ANA’s performance within the framework of MPC, including a comprehensive comparison with GA and PSO could further validate its efficiency and efficacy. Future work will incorporate detailed benchmarking of ANA against these algorithms, assessing performance metrics such as:

-

Convergence Speed: Comparison of iterations required to achieve optimal solutions under similar conditions.

-

Computational Efficiency: Assessment of resource usage and execution time.

-

Solution Quality: Evaluation of trade-offs between HC and CP achieved by each algorithm.

Such evaluations would provide deeper insights into ANA’s suitability for this application and help determine whether its advantages over GA or PSO can be generalized to other energy optimization problems.

LSTM-based MPC utilizing ant nesting algorithm

The BnZEB is put under MPC by making use of all the LSTM networks that were developed earlier to minimize fitness functions through the ANA. To reduce computational workload, the LSTM models are incorporated into the approach to carry out the multi-criteria ANA. The methodology employed in this study is outlined in Fig. 1 to provide an overview of the approach taken.

A daily MPC is conducted to tackle a multi-objective optimization problem. This problem encompasses two competitive fitness functions (FFs) that are associated with the thermal comfort and economic expenses of regulating the microclimate. The two FFs need to be minimized simultaneously and they are:

The first FF is the comfort penalty (CP) that indicates the level of discomfort experienced by occupants and is measured in degrees Celsius per hour (°Ch). The second FF is cost of the heating (HC), which reflects the cost of daily heating usage operations and is represented in cent dollars per square meter per day (c$m2 day).

To ensure the minimization of the fitness functions, it is imperative to execute the optimization process with precision. The determination of the comfort penalty function, as assessed by the adaptive comfort theory, is predicated upon the summation of positive fluctuations between the ideal temperature for comfort (\(\:{T}_{it}\)) and the indoor temperature on an hourly basis. To mitigate the adverse impact on the thermal inertia of the structure, solely the positive variances are factored in. To calculate Tot, the monthly average outdoor air dry-bulb temperature (\(\:{T}_{o}\)) was employed by means of a simple running average of the previous thirty daily average outdoor air temperatures, utilizing the methodology set forth in the ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-201033.

The determination of the operating temperature (Tit) involves the computation of the mean value between the indoor air temperature and the average radiative temperature, as specified in34. The high thermal insulation of the building results in the two temperatures being very close to each other, such that in this context, the operating temperature can be regarded as equal to the indoor air temperature. This implies that the indoor air temperature is a reliable indicator of the operating temperature, which is useful in assessing the thermal performance of the building.

For each hour of the day being studied, there are 24 decision variables that represent the setpoint temperatures within the building thermal zones. These variables can take on four different fixed values, specifically 14 °C, 20 °C, 21 °C, and 22 °C, and are selected as decision variables. The ANA settings used in this study are in line with previous research, and include a population size of 40, a fixed maximum number of iterations set to 500, and a pheromone decay rate of 0.9.

Once the Pareto set is identified using the ANA, a decision needs to be made, and this is where multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) comes into play. There are different methods available for MCDM, and in the suggested methodology, the user can choose to prioritize comfort (CP) and/or economic constraints (HC). This study centers on the upholding of fundamental indoor comfort parameters, wherein the user stipulates a ceiling for the CP value deemed tolerable. From the set of Pareto optimal solutions, the chosen solution adheres to this particular constraint whilst simultaneously minimizing HC. The main objective is to improve the energy efficiency of the building without compromising comfort. If the ANA finds a solution that increases HC, the solution that minimizes expenses for a minimum percentage alteration in CP is also assessed, taking into account the economic aspect while not neglecting the comfort aspect.

Results

Following a trial-and-error experimental methodology, it has been determined that the optimal settings for the creation of all artificial neural networks through the utilization of LSTM technology entail the implementation of 16 neurons within the hidden layer, 2 output delays, and 1 input delay. The performance of prediction with respect to the LSTM networks has been thoroughly evaluated by means of the testing set, and the findings indicate a robust correlation with the simulated data, as delineated in Table 2.

Figures 2 and 3 provide an instance of the forecasting capability of the various LSTM networks for a subset of the testing set. Specifically, Fig. 6 displays the LSTM networks designed to forecast the heating requirement at fixed setpoint temperatures of 20 °C (HR20), 21 °C (HR21), and 22 °C (HR22), while Fig. 3 illustrates the training of LSTM network for predicting the temperature of indoor space (\(\:{T}_{i}\)). The example displayed in both figures represents a limited portion of the evaluation dataset to evaluate the performance of the LSTM networks, consisting of around 160 h for heating demand and roughly 180 times for indoor temperature data.

Subsequently, the multi-objective optimization problem is handled. This entails the identification of the optimal decision variables that can lead to minimizing both the costs associated with heating (HC) and discomfort penalties fitness functions in an optimal manner. Achieving this outcome necessitates the identification of the most efficient combination of decision variables. In order to carry out the process of optimization, an assessment of three distinct winter days, specifically December 10, January 5, and February 15, has been conducted. This assessment was conducted with the objective of accounting for the various potentials that are associated with a common winter day. As detailed in part 3, 2 separate processes of optimization were executed for each day, with each optimization process being associated with a different electricity price (\(\:{P}_{el}\)) scenario. These two scenarios were designed to incorporate the possibility of fluctuations in electricity prices resulting from various factors, and involved \(\:{P}_{el}\) being either 0.328 $/kWh or 0.493 $/kWh. It is noteworthy that the cost of electricity in Europe is subject to volatility and is currently experiencing an upward trend35.

Regarding the 10th of December and a set \(\:{P}_{el}\) value of 0.328 $/kWh, the Pareto set attained is demonstrated in Figs. 4 and 5. The reference solution signifies a standard office scheduling plan, and the selected solution is also shown in part (A). For an office heating system in Norway, a conventional methodology for scheduling could involve commencing the heating process between the hours of 7:00 to 9:00 in the morning to facilitate the warming up of the workspace at the inception of the workday. This can be succeeded by an interlude of heating during midday, specifically from 11:00 to 13:00, to sustain a comfortable temperature. Lastly, another session of heating can be implemented from 16:00 to 18:00 to secure a warm office environment towards the culmination of the workday. In multi-criteria decision-making, the value assigned to the CP is subject to constraints that ensure congruence with the reference solution, which has been established at a fixed temperature of 21.82 °Ch. On the other hand, the HC value in the reference point has been calculated at a rate of 1.46 c$/m2day.

Figures 4 and 5 depicts the selection of two optimal points, wherein one satisfies the prescribed constraint on comfort penalty (CP) and the other adheres to the constraint on heating cost (HC). This underscores the significance of accounting for both the comfort and economic considerations in the optimization process. The cardinal aim is to uphold or enhance the existing comfort conditions established by the baseline approach, while simultaneously taking into account the economic repercussions. In instances where the optimal solution generated by the ant nesting algorithm fails to meet both constraints, a thorough evaluation must be carried out to determine the appropriate course of action, as is the case herein. As illustrated in above figures, a modest decrease of 5% in comfort penalty (from 10.5 to 10°Ch) can result in a remarkable cost reduction of 13.14%.

Figure 5 depicts the optimized control strategy for space heating generated through the application of ant nesting algorithm, manifesting distinguished dissimilarities from the reference approach. The findings concerning the postulates established by the temperature control system setpoint temperature are compelling and in concurrence with heat-related data. The two recommended solutions exhibit significant similarity in comparison to the standard solution, with merely minor deviations in certain setpoints. This underscores the importance of monitoring the diurnal fluctuations in extrinsic factors, such as an outside temperature and solar energy, rather than relying on predetermined schedules. The confirmed outcome was the one in which the reduction of discomfort penalty by means of decreasing it, necessitated more setpoints at a higher temperature, resulting in increased heating expenses. In contrast, the second proposal results in a 13% increase in heating expenses, while incurring an inconsequential effect on the discomfort penalty, specifically only 0.4%.

Figure 6 depicts the findings of the same analysis done on December 10, but with a higher power price of 0.493 $/kWh, which is more consistent with the current Norwegian energy marketplace36. First part of the figure demonstrates that there exists exclusively a solitary point that satisfies the two limitations, leading to a reduction of 2.7% and 1.5% in HC and CP, correspondingly.

To ensure the examination of more dependable outcomes, the research examines three distinct days. Specifically, the findings acquired on January 5 are depicted by Figs. 7 and 8, whereas Figs. 9 and 10 depict the outcomes from February 15.

Figures 7 and 8 assess the results of January 5 within both of hypothetical financial conditions under examination. In the instance when the electricity price amounts to 0.328 $/kWh, Fig. 7 reveals that merely a single Pareto-optimal data point complies with comfort and cost-related restrictions, thereby leading to a decrease of 11.7% and 3.1% for HC and CP. On the contrary, Fig. 8 exemplifies that there is no instance on the Pareto set that fulfills both restrictions when the electricity price amounts to 0.493 $/kWh. Hence, akin to the scenario witnessed on December 10 for a \(\:{P}_{el}\) value equating to 0.328 $/kWh, a decision must be made between the two constraints.

Figures 9 and 10 depict the final day scrutinized in this investigation, which coincidentally happens to be the most frigid day. The green circle in Fig. 9 represents the optimal setpoint temperatures. These temperatures correspond with the outdoor air temperature tendency, as evidenced by the dotted line. By executing this solution, a 15.5% decrease in heating expenses and 7% reduction in discomfort penalty result. The recommended optimal design suggests that a higher setpoint temperature be implemented between the hours of 5:00 to 7:00, as a result of the relatively low outdoor temperatures during this period. However, the setpoint temperatures are gradually lowered as the temperature outside during the evening begins to rise.

The following Figure presents the Pareto set gained on the 15th of February, reflecting a \(\:{P}_{el}\) ratio equal to 0.493 $/kWh. The paramount outcome, concerning HC, is attained by reducing 0.07 c$/\(\:{m}^{2}\)day in comparison to the reference solution, which records 2.64 c$/\(\:{m}^{2}\)day. The outcomes on cold days, such as February 28, manifest more positive results. With \(\:{P}_{el}\) equal to 0.328 $/kWh, the optimal point yields a 7% and 15.5% advancement in CP and HC, respectively. An improvement in CP by 18% and HC by 16.8% is observed with \(\:{P}_{el}\) equivalent to 0.493.

The paper evaluates the impact of varying electricity price scenarios ($0.328/kWh vs. $0.493/kWh) on the optimization results and highlights significant trade-offs between comfort penalty and heating costs. While these impacts are discussed qualitatively, further quantification of price sensitivity has the potential to strengthen the paper. Specifically, the results can benefit from an explicit numerical analysis detailing how both CP and HC respond proportionally to changes in electricity costs. The higher price scenario ($0.493/kWh) imposes stricter constraints on optimization, resulting in fewer solutions that satisfy both comfort and cost requirements. For instance:

-

- On December 10, the optimization achieved a modest 2.7% reduction in HC and a 1.5% decrease in CP under $0.493/kWh.

-

- In lower price scenarios ($0.328/kWh), trade-offs are more favorable, where a near 13% reduction in HC is achieved with only a 0.5% increase in CP.

Adding a sensitivity analysis—such as highlighting the incremental change in HC per unit increase in CP across scenarios—would clarify how MPC adapts to price fluctuations. Visual tools, like Pareto curve comparisons, could make these trade-offs more transparent. Finally, quantifying the overall economic impact of price volatility through a defined “price elasticity index” for heating costs would assist in illustrating the model’s practical adaptability to fluctuating market conditions. Integrating these elements would provide a clearer perspective on the MPC framework’s robustness in balancing comfort and cost across varying price regimes. These items can be interesting ideas for future work. All the outcomes of implementing this method, measured by fitness functions. This measurement provides the value and percentage comparison of the two fitness functions - comfort penalty and heating cost - for both the reference and selected solutions.

It is of utmost importance to highlight the crucial point that the BnZEB denotes an edifice that functions on almost negligible energy, leading to the bare minimum requirement for space heating. This aspect holds immense significance, as it throws light on the considerable economic benefits that can be reaped from this research when compared to buildings that lack comparable features with regards to building envelope and energy generation system. Furthermore, it is imperative to take into account the potential advantages that can be achieved by enhancing indoor conditions, which could eventually culminate in the reduction of the comfort penalty.

-

Research limitations.

The current study has some key limitations, which can also serve as potential ideas for future research:

-

(1)

The assumption of zero occupancy and lighting inputs overlooks critical internal dynamics, such as heat generated by occupants and lighting energy consumption, which are substantial contributors to office building performance. This limitation significantly affects the applicability of the model in real-world scenarios. Future implementations should incorporate occupancy patterns and lighting loads to provide a more accurate evaluation of heating requirements and building energy efficiency.

-

(2)

The fact that the model is trained exclusively on a nearly-zero energy building (nZEB) in Oslo represents a notable limitation. This is because the performance of the model could be highly sensitive to variations in HVAC systems, building envelopes, and climatic conditions. The effects of these factors are significant, as buildings with differing thermal responses, system dynamics, and weather-driven heat demands may require different model configurations or additional data for effective application. To address this limitation and expand applicability, future studies should focus on retraining the model with datasets that represent diverse building types, climate conditions, and HVAC configurations. This effort will enhance the flexibility and generalizability of the proposed approach, thereby increasing its utility for optimizing heating efficiency in a wide range of scenarios.

-

(3)

The study employs the comfort penalty (CP) metric as a core measure of occupant discomfort and optimization. While useful for numerical evaluation, the study does not fully explain how CP improvements translate into perceptible changes in occupant comfort. Future research should focus on validating CP improvements against actual occupant feedback and comfort thresholds to establish a clearer link between numerical metrics and thermal experience.

Conclusions

This research has effectively showcased the capability of employing a framework that makes use of simulation and optimization, along with an ant nesting algorithm and a LSTM network, in order to achieve MPC of space warming arrangements. The research carried out on an ultra-low energy construction situated in a Cold environment has illustrated the reliability of LSTM architectures as well as the possibility of their further optimization to improve their efficiency. The framework proposed in this study has been tested on three typical days and has demonstrated its ability to boost heating effectiveness utilizing ANA- “and ANN-based MPC”. In addition, this framework has also shown an improvement in thermal comfort when contrasted with a benchmark management tactic. This research has reached numerous notable accomplishments, which encompass the validation of the LSTM networks’ reliability by employing simulated EnergyPlus objectives, the enhancement “of their effectiveness through optimizing the datasets and parameters, the reduction of computational duration through the use of an artificial neural network, the integration of ANNs with an optimization process in an MPC logic, and the manifestation of significant savings in energy expenses and improvement in thermal comfort through the implemented space warming MPC. Indeed, the framework demonstrated potential savings in energy expenses, with results varying across different test days and maximum savings of up to 17% achieved under specific conditions, such as on the coldest days with high energy costs.

The MPC procedure developed in this study can be incorporated into building automation systems for practical applications. By feeding real occupancy patterns and weather situation, it can deliver real-time enhancement of the HVAC setup, while remaining subordinate to the user’s demands. Additionally, the employment of ANNs for MPC in building energy managing systems has the capability of substantially decreasing the computation duration in contrast to conventional simulation software like EnergyPlus. This enhanced time efficiency can result in greater efficiency and more frequent optimization of the HVAC system, which can facilitate more significant energy savings and better thermal comfort for building inhabitants. One of the key constraints is linked to the training of the networks. The precision of LSTM networks, along with other networks, is impacted by the magnitude and intricacy of the dataset employed for their training. To achieve accurate predictions, using an inclusive and substantial data set that represents the case study and building location is essential. Another limitation pertains to the requirement of constructing diverse networks for each climate to ensure the highest achievable prediction accuracy. Even for comparable buildings located in varying climatic conditions, a distinct artificial neural network is mandatory. Upcoming investigations can concentrate on enhancing the dependability of ANN further, encompassing various ANNs, and integrating measured data for training of network. Alternative feasible domain of inquiry may be analyzing the same technique during the summer period, owing to the escalating demand for cooling. These improvements could potentially offer even more substantial reductions in energy usage and better thermal comfort for structures, contributing to the global endeavor to diminish “energy consumption and mitigate climate change”. All in all, the results of this investigation carry important consequences for optimizing the performance and time efficiency of building energy management and HVAC control systems.

The proposed framework, while validated for nearly-zero energy buildings (nZEBs) in cold climates, has the potential for broader applicability across various building types (e.g., residential, commercial, and industrial) and climatic conditions (e.g., tropical or arid regions). Different building types with varied thermal characteristics and equipment configurations may require retraining of the LSTM network and calibration of the optimization model. The adaptability of the framework could be further enhanced by incorporating region-specific datasets to better capture unique operational and environmental factors.

Future research will focus on cross-regional validation by retraining the proposed model with climate data from diverse regions. This will ensure that the framework performs consistently under a range of climatic conditions, covering heating- or cooling-dominated zones. Additionally, further studies may explore extending the approach to account for occupant behavior, lighting dynamics, and internal heat loads, strengthening the model’s applicability to varied operational settings. Insights from these efforts aim to enhance the replicability of the framework and provide evidence for its practical implementation in real-world building energy management systems.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Lin, Y. et al. Impact of high-speed rail on road traffic and greenhouse gas emissions. Nat. Clim. Change. 11 (11), 952–957 (2021).

Khozin, V., Khokhryakov, O. & Nizamov., R. A carbon footprint of low water demand cements and cement-based concrete. in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing. (2020).

Yuan, K. et al. Optimal parameters Estimation of the proton exchange membrane fuel cell stacks using a combined Owl search algorithm. Energy Sour. Part A Recover. Utilization Environ. Eff. 45 (4), 11712–11732 (2023).

Sun, L. et al. Exergy analysis of a fuel cell power system and optimizing it with Fractional-order Coyote optimization algorithm. Energy Rep. 7, 7424–7433 (2021).

Ye, H. et al. High step-up interleaved dc/dc converter with high efficiency. Energy Sour. Part A 8, 1–20 (2020).

Yin, Z. & Razmjooy, N. PEMFC identification using deep learning developed by improved deer hunting optimization algorithm. Int. J. Power Energy Syst. 40(2), 189 (2020).

Rezaie, M. et al. Model parameters Estimation of the proton exchange membrane fuel cell by a modified golden Jackal optimization. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 53, 102657 (2022).

Wang, R. et al. A comprehensive evaluation of zero energy buildings in cold regions: actual performance and key technologies of cases from china, the US, and the European union. Energy 215, 118992 (2021).

Ebrahimian, H. et al. The price prediction for the energy market based on a new method. Economic research-Ekonomska Istraživanja. 31 (1), 313–337 (2018).

Hosseini, H. et al. A novel method using imperialist competitive algorithm (ICA) for controlling pitch angle in hybrid wind and PV array energy production system. Int. J. Tech. Phys. Probl. Eng. (IJTPE). 11, 145–152 (2012).

Han, E. & Ghadimi, N. Model identification of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells based on a hybrid convolutional neural network and extreme learning machine optimized by improved honey Badger algorithm. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 52, 102005 (2022).

Arroyo, J., Spiessens, F. & Helsen, L. Identification of multi-zone grey-box Building models for use in model predictive control. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 13 (4), 472–486 (2020).

Cai, W. et al. Optimal bidding and offering strategies of compressed air energy storage: A hybrid robust-stochastic approach. Renew. Energy. 143, 1–8 (2019).

Guo, Y. et al. An optimal configuration for a battery and PEM fuel cell-based hybrid energy system using developed Krill herd optimization algorithm for locomotive application. Energy Rep. 6, 885–894 (2020).

Khalilpour, M. & Razmjooy, N. Congestion management role in optimal bidding strategy using imperialist competitive algorithm. Majlesi J. energy Manage. 1(2), 56 (2012).

Chen, L. et al. Optimal modeling of combined cooling, heating, and power systems using developed African Vulture optimization: a case study in watersport complex. Energy Sour. Part A Recover. Utilization Environ. Eff. 44 (2), 4296–4317 (2022).

Fan, X. et al. Multi-objective optimization for the proper selection of the best heat pump technology in a fuel cell-heat pump micro-CHP system. Energy Rep. 6, 325–335 (2020).

Bahmanyar, D., Razmjooy, N. & Mirjalili, S. Multi-objective scheduling of IoT-enabled smart homes for energy management based on arithmetic optimization algorithm: A Node-RED and NodeMCU module-based technique. Knowl. Based Syst. 247, 108762 (2022).

Huang, Y. et al. A hierarchical coupled optimization approach for dynamic simulation of Building thermal environment and integrated planning of energy systems with supply and demand synergy. Energy. Conv. Manag. 258, 115497 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Transbts: Multimodal brain tumor segmentation using transformer. in Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, Proceedings, Part I 24. 2021. Springer. (2021).

Basu, S., You, X. & Feizi, S. On second-order group influence functions for black-box predictions. in International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR. (2020).

Lee, D. et al. Model predictive control of Building energy systems with thermal energy storage in response to occupancy variations and time-variant electricity prices. Energy Build. 225, 110291 (2020).

Du, Y., Zhou, Z. & Zhao, J. Multi-regional Building energy efficiency intelligent regulation strategy based on multi-objective optimization and model predictive control. J. Clean. Prod. 349, 131264 (2022).

Carli, R. et al. Model predictive control for thermal comfort optimization in building energy management systems. in. ieee international conference on systems, man and cybernetics (smc). 2019. IEEE. (2019).

Yang, S., Chen, W. & Wan, M. P. A machine-learning-based event-triggered model predictive control for Building energy management. Build. Environ. 233, 110101 (2023).

Weather in Oslo, Norway. [cited ; (2024). Available from: https://www.timeanddate.com/weather

Gao, H., Koch, C. & Wu, Y. Building information modelling based Building energy modelling: A review. Appl. Energy. 238, 320–343 (2019).

Ascione, F. et al. Energy refurbishment of an Office Building by addition of a second skin: Improvement of thermal behavior, energy performance and possible conversion by PV. in. 6th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech). 2021. IEEE. (2021).

Ascione, F. et al. A real industrial building: modeling, calibration and Pareto optimization of energy retrofit. J. Building Eng. 29, 101186 (2020).

Karijadi, I. & Chou, S. Y. A hybrid RF-LSTM based on CEEMDAN for improving the accuracy of Building energy consumption prediction. Energy Build. 259, 111908 (2022).

Congedo, P. M. et al. Numerical and experimental analysis of the energy performance of an air-source heat pump (ASHP) coupled with a horizontal earth-to-air heat exchanger (EAHX) in different climates. Geothermics 87, 101845 (2020).

Czachura, A. et al. Selection of Weather Files and Their Importance for Building Performance Simulations in the Light of Climate Change and Urban Heat Islands. (2021).

Aruta, G. et al. Optimizing heating operation via GA-and ANN-based model predictive control: concept for a real nearly-zero energy Building. Energy Build. 292, 113139 (2023).

Toe, D. H. C. & Kubota, T. Development of an adaptive thermal comfort equation for naturally ventilated buildings in hot–humid climates using ASHRAE RP-884 database. Front. Architect. Res. 2(3), 278–291 (2013).

Wang, H., Feng, T. & Zhong, C. Effectiveness of CO2 cost pass-through to electricity prices under electricity-carbon market coupling in China. Energy 266, 126783 (2023).

Lakshmanan, V., Sæle, H. & Degefa, M. Z. Electric water heater flexibility potential and activation impact in system operator perspective–Norwegian scenario case study. Energy 236, 121490 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zheng Qi, Nan Zhou, Xianwei Feng and Sama Abdolhosseinzadeh wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, Z., Zhou, N., Feng, X. et al. Optimizing space heating efficiency in sustainable building design a multi criteria decision making approach with model predictive control. Sci Rep 15, 27743 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13325-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13325-4