Abstract

The world’s groundwater resources are under tremendous strain due to overuse and significant climatic changes. The need for potable water for industrial, agricultural, and domestic use is increasing worldwide, necessitating an assessment of aquifer productivity and groundwater potential. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate groundwater potential zones (GWPZ) in Natham Taluk, Dindigul district, a hard rock area, to promote sustainable development. The GWPZ was delineated using the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) in conjunction with Remote Sensing (RS) and Geographic Information Systems (GIS), which have become essential techniques for groundwater resource retrieval, monitoring, and conservation. A total of ten thematic maps of lithology, land use/land cover, lineament density, geomorphology, soil, slope, rainfall, drainage density, Topographic Wetness Index (TWI), and curvature, all layers were integrated to define Groundwater Potential Zones (GWPZs) by weighted overlay analysis using ArcGIS and Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP). Five types of groundwater potential were found in the study region as a consequence of the classification: very good (7.61%), good (39.70%), moderate (17.70%), low (33.03%), and very low (1.95%). The groundwater potential map (GWPM) accuracy is evaluated using the area under the curve (AUC) method; an AUC value of 0.830 indicates a reliable result. This spatial study provides a vital geospatial database for strategically planning and constructing groundwater recharge structures. In addition to supporting the long-term sustainable management of groundwater resources, the delineated zones offer practical insights for improving aquifer recharge. The study also identifies possible locations for artificial recharge, especially well-suited to areas with hard rock and semi-arid conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Groundwater (GW) is a critical element of the human life support system and is crucial for various applications, including drinking, agriculture, industry, domestic, and other development activities. Water is a critical element of ecological systems, fuels economic growth, and is necessary for preserving life on our planet1. Magesh et al.2 assert that GW is an abundant and valuable source of fresh water, contributing approximately 34% of the total annual water supply. GW is a variable resource that is difficult to measure in time as well as place, is not immediately visible from Earth’s surface, and occurs in complex subterranean formations3. The availability of surface water for a variety of purposes in semi-arid regions is not consistent throughout the year, necessitating an increasing reliance on GW supplies for the survival of the local population4. Over time, non-scientific uses of GW for a range of reasons have caused the water table to drop at an alarming rate. In areas where fresh GW is present, it is especially common. Adequate surface water management strategies are required to optimize GW recharging5. Various hydrogeological and physico-climatic factors, including lithological structures, land use/cover, slope angle, primary and secondary porosity, drainage network, rainfall distribution, and rainfall intensity, along with other physico-climatic conditions, affect the presence of GW. These factors also identify Potential GW zones6.

The Groundwater Potential (GWP) can be raised using ponds, rivers, and other surface water sources as recharge zones. Therefore, it is imperative to identify and quantify these attributes to create a potential GW model for a specific location7. In the past, Groundwater Potential Zones (GWPZs) have been precisely recognized using a variety of traditional techniques that are both time-consuming and expensive, such as geological, hydrogeological, geophysical, and photogeological methods8. Numerous researchers have employed RS and GIS applications worldwide to investigate GWPZ in recent years due to their affordability, dependability, and rapidity9. “Satellite RS data conforms to the fundamental criteria for data in a GIS1. These methods enhance the precision of GWPZ delineation outcomes and mitigate bias toward any theme10. SOI top sheets, collateral information, and RS data analysis are all employed to establish baseline data for mapping GWPZs and to confirm the veracity of findings obtained through RS and GIS analysis11,12. The methodologies used to determine GW recharge volumes outlined the characteristics of each technique and recommended the most effective approaches for” future GW recharge studies. Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) procedures, in conjunction with geospatial tools such as RS data and GIS, have been demonstrated to be effective in the identification of GW zones13.

The value of “geophysical and geospatial methods in mapping regional GW potential and improving GW management practices” is underscored by the comprehensive investigation that resulted in the development of an aspirational GW zoning strategy in Ilorin employing RS, geospatial data, and geophysical techniques. For GW to be used sustainably and for irrigation systems to be improved, potential GW locations must be identified14,15. To map GWPZs in the arid regions of Qina and Safga Bir Queh, Egypt, employing “Multi-Criteria Evaluation (MCE)” and AHP approaches concerning RS and GIS data, GW wells will be developed to assist water supply, food production, and urban expansion16.

Saaty’s AHP, a widely used multi-criteria decision-making technique (MCDM), is often integrated with RS and GIS environments to enhance spatial analysis techniques for planning water resources because it is simple, dependable, and economical. Before incorporating themes in GIS, the AHP is frequently used to provide appropriate weights. It analyzes various datasets as a pairwise matrix, generating geometric mean (GM) and normalized weight parameters using expert judgment and prior research studies17. AHP has been widely used in conjunction with RS and GIS tools to locate and assess GWPZ, according to numerous studies that show the significance of RS, GIS, and AHP are to monitoring, evaluation, conservation, and sustainable management of GW resources for future use1,3,10,1618–21. According to6 among the numerous investigations, the AHP method is the most promising of the models because it chooses its layers according to their effects and data availability.

There hasn’t been any comparable research done in the subject area. There is no such study data available for GW resources due to a lack of future management. For this reason, this investigation is vital for researchers, decision-makers, and policymakers who want to enhance socioeconomic management of GW resources.

Thus, utilising geospatial methods, the current study was carried out for Natham Taluk’s hard rock terrain. The work done for the study area is unique and creative. This work is distinct as it employs an integrated method of RS, GIS, and AHP to validate delineated GWPZs by employing well-yield data and to provide new thematic qualities in addition to the data available for GWPZ delineation. To facilitate the most efficient and sustainable management of GW resources, the investigation intends to determine GWPZ within the research area and develop a possible GW exploration roadmap. Since a substantial portion of the study area is made up of agricultural land, this investigation aims to improve irrigation systems and enhance regional agricultural output.

Regarding the study’s limitations, open wells within the study area were sufficiently dry. Therefore, monitoring the water table is the most challenging task in the research region. Although there are many tube wells in the research region, it wasn’t easy to make it convenient for farmers to monitor the water table in the tube wells.

Materials and methods

Study area

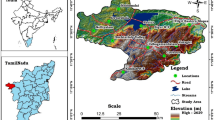

The study area is Natham taluk, Dindigul district, Tamil Nadu, India, with coordinates 10°10’ and 10°20’ N latitude and longitude 78°10’ and 78°30’ E (Fig. 1). An area of 574.49 km2 was included in the area of interest. It is surrounded by the Eastern Ghats, which are densely forested and rich in wildlife. The average temperature in this area ranges from 25 °C to 37 °C. The yearly rainfall in this district ranges from 700 to 1600 mm. Most of the study area comprises rough, undulating terrain with several hillocks. The drainage pattern is generally subparallel in the hillocks and dendritic in the plains. The geological structures mainly control the drainage. The altitude of the study area ranges from 192 to 919 m.

Base map of the study area (This figure was prepared using ArcGIS Desktop 10.7 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview).

Methods of thematic map Preparation

To identify the groundwater potential zones of the Natham taluk, this paper used AHP technique based on GIS and knowledge-based factor analysis of 10 layers of local data, including lithology, land use/land cover, lineament density, geomorphology, soil, slope, rainfall, drainage density, Topographic Wetness Index (TWI), and curvature. ERDAS Imagine was used for the pre-processing (image processing) analysis of the remote sensing data of the study area. Using ArcGIS 10.7 software, geographic information techniques were demonstrated. Using the hydrology function in GIS software, a drainage and slope map was prepared from the Shuttle Radar Topographic Mission (SRTM-30 m resolution). LULC and geomorphology were prepared using geo-coded false color composite satellite data from the ESRI Sentinel-2/ USGS.

The Geological Survey of India, the Department of Agriculture, Tamil Nadu, Government of India, and the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) provided the soil data. SRTM was used to generate the roughness, slope, and curvature. The Indian Meteorological Department provided the rainfall data. The spatial distribution of rainfall was created using an inverse distance weighted (IDW) interpolation method. Automatic extraction techniques were used to extract drainage and lineaments from SRTM (30 m) data. Line density in spatial analysis was used to prepare the density from the drainage and lineament.

A GIS software analysis tool. The “TOPMODEL” index served as the basis for creating the topographic wetness index. The Jenness algorithm was used to prepare the topographic position index. Table 1 lists the various published data sources that were gathered and digitized.

The Central Groundwater Board (CGWB) provided a groundwater observation well (depth to the water table) for verification. The results were also validated using the Area under the Curve (AUC) and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC), which were plotted using the ArcSDM tool in ArcGIS software. By contrasting the produced recharge groundwater potential map with the actual bore well data, the ROC curve analysis was utilized for quantitative validation. The ROC curve analysis is a common technique for assessing the reliability of diagnostic tests22. True positive values are represented along the y-axis rate for ROC, whereas false positive values are plotted along the x-axis. The ROC curve describes a balance between the two values23.

The GIS system makes managing greater spatial and nonspatial data easier, while the “theme maps were geo-rectified and projected in zone-43 North UTM.” Fig. 2 presents the overall methods used in this study. Validation is the most critical procedure for verifying the reliability and accuracy of the data utilized in these models. The common and advanced techniques for evaluating model performance in inventory locations, such as borewells, are field observation, Google Earth Pro, GIS, and AUC methods validation maps. The data from 51 available wells were used to establish and cross-check the GWPZ in this research. The well location is shown in Table 2.

AHP method for GWP zoning

This study uses Saaty’s (1980) Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to evaluate the impact of different thematic layers and their attributes on groundwater potential. AHP generates a priority scale from these relative evaluations by allocating weights to each parameter according to the decision-maker’s pairwise comparisons1. Based on prior research and expert judgment, each criterion was assigned a relative relevance rating on a scale of 1 to 9. As advised by24, a structured pairwise comparison matrix (PCM) was used to assess thematic components. According to25,26, layers with higher weights have a bigger impact on groundwater potential, while layers with lower weights have a negligible effect. One of the most used GIS-based techniques for defining groundwater potential zones is still AHP. The criteria were compared in pairs and recorded in a PCM by the17 framework (see Table 3). Using typical AHP procedures, the final weights of each thematic layer were calculated27. Saaty and Vargas28 developed AHP, which is also known as the Saaty approach17,28,29,30,31. The objective of solving multi-criteria decision-making situations accurately is usually preferred. AHP analysis can generate a significance test of the characteristics by employing a pairwise comparison to help determine the relative relevance of certain attributes. Saaty used mathematical calculations to determine the most effective response in a multi-criteria analysis. AHP uses computation methods and mathematics to generate a matrix that shows the relative values of a set of attributes. AHP analysis was conducted using a series of calculations on the common scale modified from Saaty. The calculation is described below.

First, add values in each column of PCM by employing Eq. 1:

Here Lj = “total values in each column of a pairwise matrix and Cij number assigned to each factor at ith row and jth column.

Second, divide each element in the matrix by its column total to generate a normalised pairwise matrix” by employing Eq. 2:

Here Xij = “value at ith row and jth column in the normalised pairwise matrix”.

“Finally, divide the sum of the normalised row of the matrix by a number of factors used (8 for the current study) to generate standard weights by employing Eq. 3:

Where Wi = Standard weight and N = number of factors.

“Consistency ratio (CR)” has been calculated to find any discrepancies and” determine best weights after the PCM has been finished and the weights of its components have been determined. Only when the CR was 0.1 or less did the AHP analysis move forward. However, inconsistencies in the review process could result in erroneous results if CR > 0.1. CR was established for the matrix by comparing “consistency index (CI)” and “random index (RI)” to evaluate the reliability of relative weights. CI was determined utilizing Eq. 4. RI in the present investigation is 1.41, as indicated in Tables 3 and 417,28.

“Where λ = consistency vector. n = number of factors used.

Consistency ratio was measured by employing Eq. 5.

Here, “CI and CR " mean consistency index and consistency ratio, respectively.

Topographic wetness index

“A terrain-based indicator, the topography Wetness Index (TWI) measures the spatial distribution of soil moisture or water accumulation according to topography features. The first step in computing TWI is to determine the upslope contributing area for each cell by calculating flow accumulation using the SRTM DEM (30 m resolution). This is accomplished by adding up the area that contributes to the flow and following the flow pathways from each cell to its downslope neighbors. The elevation differences between each cell and its surrounding neighbors are then used to calculate the slope for each cell, which can be reported in degrees or as a percentage. These two parameters, flow accumulation and slope, are then used to calculate TWI, which helps identify areas likely to retain moisture and, therefore, potential groundwater recharge zones.

TWI calculation: TWI is determined by flow accumulation and slope measurements. A widely utilized method for computing TWI involves the logarithmic transformation of the ratio of slope to flow accumulation, expressed as follows:

Where a denotes flow accumulation and ß denotes slope angle in radians.

Results

Assignment of weights to the thematic layers using AHP

Chosen thematic layers were given ranks by employing the AHP analysis approach based on the Saaty scale. The pairwise comparison matrix was computed using the GW-influencing regime (Table 5). CI was then evaluated; consistency ratio results were analysed; the thematic layers were given normalised weights according to their significance (Table 6). Final weights for these features were determined by multiplying the average weights of thematic layers (Table 5) by the average weights of each sub-feature within each thematic layer. A set of formulas is employed to compute the AHP analysis. According to the Saaty method, which assigns ranks of equal significance to layers that have equal influencing criteria for targeting GW, “lithology layer has been given the highest weightage in this research, followed by lineament density and geomorphology. If a layer has a higher priority, the highest rank is provided.

Lithology

GWPZs are determined by geological units along with their characteristics, such as porosity, permeability, weathering, and fractures. In addition to their relationship to the study area, several lithology units have been found, including gneiss, anorthosite, granite, charnockite, khondalite, migmatite, and pegmatite (Fig. 3a). The source of the map was prepared from GSI https://bhukosh.gsi.gov.in/Bhukosh/MapViewer.aspx. Weights were assigned to each of these units according to how much of an impact they had on GW potential.

Geomorphology

GWPZs are mostly determined by geomorphological features, including landforms and Earth’s surface features. Topography, drainage patterns, and different geomorphologic units are the main elements that affect GW potential based on geomorphology. Initially, obtaining appropriate satellite imagery, such as Landsat-8, and pertinent topographic data, such as DEMs (Digital Elevation Models), is the first step in creating a geomorphological map utilizing remote sensing and GIS. Enhance the images for improved visual interpretation and preprocess the data by applying geometric and radiometric modifications. Determine and distinguish landforms, including structural hills, pediplain, and denudational hills (Fig. 3b) using image interpretation techniques (visual or digital categorization) based on shape, texture, tone, and association.

Lineament density

Lineaments on the Earth’s surface are linear structures usually resulting from structurally controlled geological faults or long, linear natural features like intrusions. These can be identified by a linear coastline, fault-aligned valleys, continuous hills aligned with folds or faults, or any combination of these. Faulting and fracturing zones are indicated by lineaments, which raise secondary porosity and permeability4. This research used the “GSI lineament map” to assess GWPZ. The ArcGIS platform was employed to create a lineament density map. Five classifications were then distinguished based on density: very high, high, moderate, low, and very low. The likelihood of GW occurrence increases with density. As a result, the extremely low ranges were given the lowest weight, and the very high ranges the highest. The pairwise comparison matrix’s consistency was examined using the AHP analysis and determined to be satisfactory. A weighted lineament density map (Fig. 3c) was created by employing normalized and final weights.

Soil

Since most soils permit water to percolate beneath the surface, enhancing infiltration capacity, they are the most significant indicators of GWPZ. As a result, soils are prioritized more highly (ranked 9). Certain soils are classified as 1 because they do not permit water infiltration. For example, the ALFISOLS group soils on mild slopes are well-drained and somewhat erosion-resistant soils that were prioritized. A lesser priority was assigned to rock outcrops in hilly areas with shallow, gravelly clay soils and moderate to severe erosion.

“Infiltration capacity, water-holding capacity, soil texture, permeability and structure, land slope, soil depth, drainage, and soil chemistry” were used to group similar soil properties (Table 3). In order to ascertain how soils impact GW conditions and to create a weighted soil map (Fig. 3d), these parameters were used to rank and analyze the soils using the AHP approach.

Land use/land cover

The analysis employed the level 3 classes and LU/LC map obtained from the GSI portal. LU/LC characteristics were ranked using GW regime and examined using the pairwise comparison approach. AHP analysis assessed the importance of matrix’s CR to rank the thematic layers. GW exploration efforts concentrate on water bodies and river features, as well as land areas (Fig. 3e).

Drainage density

Drainage patterns and systems, which influence GW circulation, recharge, and discharge, significantly influence the identification of GWPZ. A quantitative metric termed drainage density is employed to determine “the density or abundance of stream channels in the study area; in other words, it gives information about connectivity and dispersion of stream channels. The total length of streams or channels per unit area (km/km2) is commonly used to represent drainage density32,33. Drainage patterns were developed utilizing SRTM DEM data and confirmed via a toposheet. A drainage density map”, ranging from 0 to 2.33 km/km2, was constructed utilising the ArcGIS platform and is displayed in Fig. 3f.

Rainfall

Rainfall can percolate through the unsaturated zone and permeate the soil when it falls on the land surface, eventually reaching the GW reservoirs. One major source of GW recharge is rainfall, and the rate of recharge is directly impacted by the quantity, intensity, and distribution of rainfall. Rainfall has a major impact on GW recharge and the overall availability of GW resources, and it is a crucial factor in assessing GW potential. Larger GW potential and more recharge usually result from longer rainfall episodes32,33. When evaluating GW potential, rainfall patterns and spatial distribution are crucial factors to consider. Tamil Nadu PWD supplied average annual rainfall data from 2009 to 2022. Additionally, ArcGIS was used to import the rain gauge locations, and the IDW interpolation method, as seen in Fig. 3g, was used to create an average annual rainfall spatial distribution map.

Slope

Slope, steepness, or inclination of the ground surface is generally described as the ratio of vertical rise to horizontal distance. To put it simply, the ground slope shows how steep or mild a certain piece of land is. The land surface’s slope influences the rate at which water penetrates the soil. Water might move slowly and have more opportunity to seep into the earth on gentle slopes. This encourages increased GW potential and recharge rates. Conversely, steep slopes may hinder infiltration, resulting in decreased GW potential and recharge32,33. Study’s slope map, which extends from 0 ° to 79 ° (Fig. 3h), was created using SRTM (30 m) data.

Topographic wetness index

The corresponding TWI values in the SRTM (30 m) show each cell’s relative wetness or capacity to accumulate water. Places with higher TWI values are more likely to be wet or have the ability to accumulate water, which can help recharge GW; places with lower TWI values are drier. As a result, TWI indirectly represents regions with a higher potential for GW recharging or possible GW occurrence. The landscape’s topological features help identify areas vulnerable to waterlogging, wetland formation, or GW recharge34. These areas are depicted in Fig. 3i.

Curvature

Curvature is a mathematical metric employed to describe the “shape or curvature of Earth’s surface. The surface’s deviation from flatness is measured. Curvature can provide crucial information about the topography and morphology of the ground. It’s produced using elevation data obtained via RS methods. Curvature indicates the direction of GW flow. High positive curvature demonstrates convex places where GW may discharge or flow outward. Conversely, substantial negative curvature indicates concave areas where GW may converge or replenish. The direction of flow can be used to identify potential GW recharge and discharge zones. Curvature assists in discovering areas where GW accumulates or is stored. GW accumulates in regions with significant positive curvature as water converges and releases as surface runoff”. However, when water seeps into the ground and accumulates, areas with a significant negative curvature may be signs of GW recharge35,36. (Fig. 3j).

Discussion

Mapping of groundwater potential zones

Through the use of a pairwise comparison approach, AHP analysis, and multicriteria decision-making, this study identified GWPZs by ranking features of thematic layers based on expert knowledge and GW-affecting factors. With the use of SRTM (30 m) data, numerous thematic layers, such as slope, curvature, drainage density, and TWI, were mapped. Saaty’s approach was used to classify and rank the features according to the GW regime. The developed theme layers included LU/LC maps, soil, lineament, geology, geomorphology, and yearly average rainfall. All layers were finally weighted using “AHP technique to employ weighted overlay analysis in the ArcGIS platform to find GWPZ. Table 7 displays weights and ranks assigned to layers and each layer’s characteristics and consistency index value. The GW potential map was finally completed.

Very high potential zones comprise a very small portion of the research region, approximately 7.61% of total GWPZ observed in Fig. 4. These areas are shown in dark blue on the GWPZ map. ALFISOLS is the predominant soil type in the northern part of the Pillaiyarnattam Block, which is related to a gentle slope regime that is well-drained and slightly eroded. They have been identified in the central region of the Sendurai, Pannuvarpatti, and Uralipatti blocks, where the weathered zone is thick. In the Natham Taluk, high-potential GW-rich zones are present in 39.79% of the total area. These high-potential regions are observed in the northern portion of the Sendurai Block, the central Natham, the northeastern and southeast portions of the Lingavadi Block, and the severely fractured regions of the Velampatti, Panniyanmalai, Sattambadi, and Seithur Blocks. These areas are shown on the map as dark blue.

The northwest section of the research region, which includes the majority of Sendurai, Kudagipatti, and the northern parts of Pudur, is home to the moderate zones, which comprise 17.70% of the entire area. On the map, these areas are shown as light sky blue. 33.3% of the area is made up of lower potential regions. 1.95% of the land is covered by very low potential zones, primarily found in mountainous areas with high rates of erosion, low topsoil thickness, and clayey soil types with undulating terrain, particularly in high hill ranges.

Validation of groundwater potential zones

Borewell depth data, a crucial indicator of subsurface water availability, was used to validate the identified groundwater potential zones. A useful and field-based metric that represents groundwater accessibility in various zones is borewell depth. While deeper borewells imply comparatively lesser groundwater availability, shallower borewells typically correlate with locations with higher groundwater potential. The accuracy and applicability of the groundwater potential zoning can be improved by evaluating the dependability of the groundwater suitability categorization through a geographic correlation between the borewell depth measurements and the mapped potential zones. The validation results show that Box A has low to very low potential, 34.99%, and Box B has high to very high potential, 47.31 and moderate potential, 17.70%. The spatial validation GWP map is shown in Fig. 5.

With an AUC of 0.830, the groundwater potential model’s validation ROC curve demonstrates a high degree of discriminative capacity Fig. 6. This shows that, depending on the input geographical characteristics, the model can accurately distinguish between groundwater-prone and non-prone locations. The model’s usefulness for decision-making in groundwater resource management is supported by its performance being significantly better than random guessing.

Conclusions

This research used a hybrid multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) method incorporating the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) and weighted overlay analysis in a Geographic Information System (GIS) for the demarcation of Groundwater Potential Zones (GWPZs) in Natham Taluk, Dindigul District, Tamil Nadu. Five classes of GWPZ from very high to very low were determined using ten thematic maps such as lithology, lineament density, geomorphology, slope, land use/land cover, soil type, rainfall, drainage density, topographic wetness index (TWI), and curvature.

The results emphasize that terrain characteristics, land use, and geological structure have strong impacts on groundwater potential. High to very high potential areas dominated the areas of favorable lithology (e.g., gneiss and granite), moderate relief, and good drainage conditions. On steep relief, shallow soils, and low fracture permeability, low to very low potential areas dominated.

The predictive model of the study attained an optimal Area Under the Curve (AUC) measure of 0.830 on the ROC curve, validating its performance in distinguishing between groundwater-prone and non-prone areas. Model accuracy was also validated based on borewell data and field verifications, further validating the spatial integrity of the findings.

In light of these encouraging results, the research also recognizes a few caveats, specifically with regards to the resolution and precision of geological and remote sensing data. Such data are susceptible to missing micro-level variability in complex terrains. Future studies need to improve the quality of the data through intensive field surveys, long-term hydrological monitoring, and high-resolution satellite data use.

The results are useful to policymakers and planners by facilitating effective land-use planning through the delivery of properly informed planning, informing the application of site-specific groundwater recharge measures (e.g., percolation ponds in low-potential areas), and facilitating sustainable groundwater abstraction. Ongoing groundwater monitoring and linkage of groundwater with regional schemes of water planning are also highlighted. The effects of climate change on groundwater resources need to be examined in further research to aid in the formulation of adaptive and resilient groundwater management actions.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Kumar Gautam, V. et al. Exploration of groundwater potential zones mapping for hard rock region in the Jakham river basin using Geospatial techniques and aquifer parameters. Adv. Space Res. 71(6), 2892–2908. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ASR.2022.11.022 (2023).

Magesh, N. S., Chandrasekar, N. & Soundranayagam, J. P. Delineation of groundwater potential zones in Theni district, Tamil nadu, using remote sensing, GIS and MIF techniques. Geosci. Front. 3(2), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsf.2011.10.007 (2012).

Ghorbani Nejad, S., Falah, F., Daneshfar, M., Haghizadeh, A. & Rahmati, O. Delineation of groundwater potential zones using remote sensing and GIS-based data-driven models. Geocarto Int. 32(2), 167–187 (2017).

Arulbalaji, P., Padmalal, D. & Sreelash, K. GIS and AHP techniques based delineation of groundwater potential zones: a case study from Southern Western ghats, India. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-38567-x (2019).

Chaudhary, B. S. & Kumar, S. Identification of groundwater potential zones using remote sensing and GIS of K-J watershed, India. J. Geol. Soc. India. 91(6), 717–721. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12594-018-0929-3/METRICS (2018).

Machiwal, D. & Singh, P. K. Comparing GIS-based multi-criteria decision-making and boolean logic modelling approaches for delineating groundwater recharge zones. Arab. J. Geosci. 8(12), 10675–10691. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12517-015-2002-5/FIGURES/10 (2015).

Arkoprovo, B., Adarsa, J. & Prakash, S. S. Delineation of Groundwater potential zones using satellite remote sensing and geographic information system techniques: A case study from Ganjam district, Orissa, India. Res. J. Recent Sci. 1(9), 59 (2012).

Suryawanshi, S. L. et al. Assessment of groundwater potential zones for hard rock area of Sabi river basin using an integrated approach of remote sensing, GIS and AHP techniques. Phys. Chem. Earth. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2024.103820 (2025).

Rehman, A. et al. Groundwater potential zone mapping using GIS and remote sensing based models for sustainable groundwater management. Geocarto Int. https://doi.org/10.1080/10106049.2024.2306275 (2024).

Pinto, D., Shrestha, S., Babel, M. S. & Ninsawat, S. Delineation of groundwater potential zones in the Comoro watershed, Timor Leste using GIS, remote sensing and analytic hierarchy process (AHP) technique. Appl. Water Sci. 7(1), 503–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-015-0270-6 (2017).

Ranganathan, M., Karuppannan, S., Murugasen, B., Brhane, G. K. & Panneerselvam, B. Assessment of groundwater prospective zone in adigrat town and its surrounding area using geospatial technology. Climate Change Impact on Groundwater Resources: Human Health Risk Assessment in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions 387–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04707-7_21 (2022)

Verma, N. & Patel, R. K. Delineation of groundwater potential zones in lower Rihand river basin, India using Geospatial techniques and AHP. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 24(3), 559–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJRS.2021.03.005 (2021).

Mohammed, O. A. & Sayl, K. N. A GIS-based multicriteria decision for groundwater potential zone in the west desert of Iraq. in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (IOP Publishing Ltd, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/856/1/012049

Yadeta, W., Karuppannan, S., Diriba, D. & Shube, H. Identification of groundwater potential zones for sustainable groundwater resource management using an integrated approach in Sirkole watershed, Western Ethiopia. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GSD.2024.101328 (2024).

Ishola, K. S. et al. Groundwater potential mapping in hard rock terrain using remote sensing, Geospatial and aeromagnetic data. Geosyst. Geoenvironment. 2(1), 100107. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GEOGEO.2022.100107 (2023).

Khan, M. Y. A., Elkashouty, M. & Tian, F. Mapping groundwater potential zones using analytical hierarchical process and multicriteria evaluation in the central Eastern desert, Egypt. Water (Switzerland). 14(7), 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/W14071041/S1 (2022).

Saaty, T. L. How to make a decision: the analytic hierarchy process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 48(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-2217(90)90057-I (1990).

Diriba, D., Karuppannan, S., Takele, T. & Husein, M. Delineation of groundwater potential zonation using geoinformatics and AHP techniques with remote sensing data. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25532 (2024).

Kalaivanan, K., Gurugnanam, B., Pourghasemi, H. R., Suresh, M. & Kumaravel, S. Spatial assessment of groundwater quality using water quality index and hydrochemical indices in the Kodavanar sub-basin, Tamil nadu, India. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 4(3), 627–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40899-017-0148-X (2018).

Fashae, O. A., Tijani, M. N., Talabi, A. O. & Adedeji, O. I. Delineation of groundwater potential zones in the crystalline basement terrain of SW-Nigeria: an integrated GIS and remote sensing approach. Appl. Water Sci. Vol. 4(1), 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/S13201-013-0127-9 (2013).

Machiwal, D., Jha, M. K. & Mal, B. C. Assessment of groundwater potential in a Semi-Arid region of India using remote sensing, GIS and MCDM techniques. Water Resour. Manage. 25(5), 1359–1386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-010-9749-y (2010).

Metz, C. E. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Semin Nucl. Med. 8(4), 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-2998(78)80014-2 (1978).

Negnevitsky: Artificial intelligence: a guide to… Google Scholar. Accessed: May 21, 2025. [Online]. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Artificial%20intelligence%3A%20a%20guide%20to%20intelligent%20systems&publication_year=2002&author=Negnevitsky%2CM

Bera, A., Mukhopadhyay, B. P., Chowdhury, P., Ghosh, A. & Biswas, S. Groundwater vulnerability assessment using GIS-based DRASTIC model in Nangasai river basin, India with special emphasis on agricultural contamination. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112085 (2021).

Machiwal, D., Jha, M. K. & Mal, B. C. Assessment of groundwater potential in a Semi-Arid region of India using remote sensing, GIS and MCDM techniques. Water Resour. Manage. 25(5), 1359–1386. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11269-010-9749-Y/METRICS (2011).

Rajasekhar, M., Upendra, B., Raju, G. S. & Anand Identification of groundwater potential zones in Southern India using Geospatial and decision-making approaches. Appl. Water Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/S13201-022-01603-9 (2022).

Muralitharan, J. & Palanivel, K. Groundwater targeting using remote sensing, geographical information system and analytical hierarchy process method in hard rock aquifer system, Karur district, Tamil nadu, India. Earth Sci. Inf. 8(4), 827–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12145-015-0213-7/TABLES/15 (2015).

Saaty, T. L. & Vargas, L. G. Hierarchical analysis of behavior in competition: prediction in chess. Behav. Sci. 25(3), 180–191 (1980).

Saaty, T. L. Decision-making with the AHP: why is the principal eigenvector necessary. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 145(1), 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-2217(02)00227-8 (2003).

Wang, J. & Chakraborty, C. H. O.-E. Of decision, and undefined 2008, the analytic hierarchy process: structuring, measurement, and synthesis. Encyclopedia Decis. Mak. Decis. Support Technologies (2008).

Muralitharan, J. & Informatics, K. P. E. S. and undefined Groundwater targeting using remote sensing, geographical information system and analytical hierarchy process method in hard rock aquifer system, Earth Science Informatics 8(4), 827–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12145-015-0213-7 (2015).

Todd, D. & Mays, L. Groundwater hydrology. Accessed: May 14, 2025. [Online]. (2004). Available: https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=X3T6DwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA32&dq=Todd,+D.K.,+1959.+Ground+Water+Hydrology.+John+Wiley+and+Sons,+Inc.,+New+York,++p.+336.&ots=TXK8m2UeKX&sig=A0gaWiPAw3EFzdhi_vmLSeQutTM

Hiscock, K. & Bense, V. Hydrogeology: principles and practice. Accessed: May 14, 2025. [Online]. (2014). https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Do9UAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=Kevin+M.+Hiscock,+Victor+F.+Bense+2014,+Hydrogeology-+Principles+and+Practices.+Wiley.+Edition+(2),+ISBN:+9780470656631&ots=-N1ONZk1gd&sig=asEr0vctMe0mGxSZYMKFs2i3tdw

Rózycka, M., Migoń, P. & Michniewicz, A. Topographic wetness index and terrain ruggedness index in geomorphic characterisation of landslide terrains, on examples from the sudetes, SW Poland. Z. Für Geomorphologie. 61, 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1127/ZFG_SUPPL/2016/0328 (2017).

Naghibi, S. A., Pourghasemi, H. R. & Dixon, B. GIS-based groundwater potential mapping using boosted regression tree, classification and regression tree, and random forest machine learning models in Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 188(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10661-015-5049-6 (2016).

Park, S., Hamm, S. Y., Jeon, H. T. & Kim, J. Evaluation of logistic regression and multivariate adaptive regression spline models for groundwater potential mapping using R and GIS. Sustainability https://doi.org/10.3390/SU9071157 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

“Gurugnanam Balasubramaniyan: Supervision, Validation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; Deiva Arul Ganesan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing- Original draft preparation; Bagyaraj Murugesan: Data curation, helps in the interpretation of data, Map preparation, Writing- Original draft preparation - Writing- Reviewing and Editing. Bairavi Swaminathan: Assist in Reviewing and Editing; Shankar Karuppannan: Data curation, Visualization, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; Karunanidhi Duraisamy: Reviewing and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. “.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Balasubramaniyan, G., Ganesan, D.A., Murugesan, B. et al. AHP and Geospatial technology-based assessment of groundwater potential zones in Natham taluk, Tamil nadu, India. Sci Rep 15, 28045 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13829-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13829-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Machine learning-based groundwater potential mapping and factor analysis in tropical lateritic terrains using self-organizing maps and random forest

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2025)