Abstract

Short birth interval (SBI), defined as < 33 months between two consecutive live births, remains a pressing public health concern in Nigeria, with potential adverse consequences for both mothers and children. Understanding the factors associated with SBI is crucial for developing effective interventions to improve maternal and child health outcomes. This study investigates the sociodemographic and regional disparities influencing SBI among women of reproductive age in Nigeria, utilizing data from the 2018 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS). This study analysed data from 25,280 women of reproductive age who had given birth within five years preceding the NDHS survey. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess the relationship between SBI and associated factors. Prevalence rates were analysed and presented using map and chart to highlight regional disparities. The overall prevalence of SBI in Nigeria was 51.6%. Older age was associated with a higher likelihood of optimal birth interval (AOR = 3.23, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.32–4.50, p < 0.001). Women in the South East (55.3%) and North West (52.2%) regions had the highest prevalence of SBI, while the South West had the lowest (38.4%). South East had lower odds of optimal BI (AOR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.59–0.75, p < 0.001) compared to the North Central region. Higher education (AOR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.74–0.99, p = 0.03) was associated with reduced odds of SBI, but wealth index did not show significant associations in the adjusted analysis. This study highlights significant regional disparities in short birth interval SBI in Nigeria. Interventions addressing regional and educational disparities, particularly in underserved regions, are essential for promoting optimal birth intervals and improving maternal and child health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Short birth intervals (SBI), defined as the time between consecutive live births being less than 33 months, pose significant risks to maternal and child health. Research indicates that short intervals between pregnancies are associated with adverse outcomes such as low birth weight, preterm birth, and increased neonatal and maternal mortality1,2. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a minimum of 24 months between consecutive births to allow sufficient time for maternal recovery and to mitigate these negative outcomes3. Despite this guidance, short birth intervals remain a persistent public health challenge in many low and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Nigeria4.

Nigeria, as Africa’s most populous nation, faces substantial maternal and child health challenges5,6. The prevalence of SBI contributes to alarmingly high maternal and neonatal mortality rates7. Although there have been efforts to enhance family planning services, the rates of SBIs remain elevated in certain regions of the country8. This situation is exacerbated by regional disparities in healthcare access, cultural practices, and socioeconomic factors, which lead to significant variations in birth spacing practices across Nigeria9,10. These disparities raise critical questions about the sociocultural and economic factors influencing birth intervals and their implications for maternal and child health5.

Several sociodemographic factors have been identified as determinants of birth spacing11,12. Education plays a pivotal role in shaping reproductive health behaviors; women with higher educational levels are more likely to utilize family planning methods and practice optimal birth spacing compared to their less educated counterparts13. Education enhances women’s autonomy, empowering them to make informed decisions regarding their reproductive health14. Similarly, wealth is another crucial factor influencing access to family planning services. Women from wealthier households typically have better access to healthcare facilities and can afford contraceptives, facilitating effective pregnancy planning and spacing15. Conversely, women in lower socioeconomic strata often encounter barriers that hinder their ability to access necessary reproductive health services16.

Geographic disparities also significantly impact birth intervals. Women residing in rural areas, particularly in northern Nigeria, face greater challenges accessing family planning services due to limited healthcare facilities and the considerable distances they must travel for care17,18. This limited access often results to higher rates of SBI in these regions. Regional variation in cultural and religious beliefs further shape reproductive behaviours and birth spacing practices19. In northern Nigeria, traditional and religious values may discourage the use of modern contraceptives, contributing to a higher prevalence of SBI10. In contrast, southern Nigeria which is characterized by greater urbanization and economic development, tends to exhibit better access to healthcare services and higher contraceptive use, contributing to longer birth intervals20.

This study aims to examine the sociodemographic and regional factors associated with SBI. By exploring the relationships between these sociodemographic factors and SBI, the study seeks to provide insights into the key drivers of SBI and the underlying regional disparities. Understanding these determinants is essential for developing targeted interventions that promote optimal birth spacing, thereby reducing the risks associated with closely spaced pregnancies and improving maternal and child health outcomes in Nigeria. Additionally, recent studies from Nigeria have explored SBI patterns following miscarriage, live birth, and caesarean Sects21,22,23,24., highlighting the complexity of factors influencing birth spacing in diverse reproductive contexts.

Methods

Study setting and design

This research is a cross-sectional study based on data from the 2018 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS), a nationally representative household survey conducted across all six geopolitical zones of Nigeria. Nigeria, located in West Africa, is the most populous African nation, characterized by significant socio-economic, cultural, and healthcare access disparities. The country’s maternal and child health outcomes remain challenging, with cultural and regional differences influencing reproductive behaviours, including birth spacing.

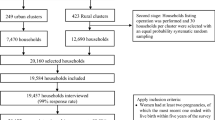

Data source and sample size

This study utilized data from the NDHS which is a comprehensive national survey executed by the National Population Commission. The NDHS is designed to gather extensive information on various demographic and health indicators, with a significant emphasis on reproductive health. Access to the dataset was obtained through the official DHS program database, ensuring compliance with all necessary authorization protocols. For this analysis, the Individual Record (IR) file was specifically utilized to extract pertinent variables relevant to the objectives of study. The target population for this study included women aged 15 to 49 years who reported their previous birth interval during the survey. A total of 25,280 women aged 15–49 years who reported their previous birth interval during the survey were included in the analysis.

Study variables

Outcome variable

The primary outcome variable was the birth interval, defined as short if less than 33 months and optimal if 33 months or more, consistent with WHO recommendations., which recommend a minimum spacing of 24 months between pregnancies to reduce the risk of adverse maternal and child health outcomes3. It is calculated as the time elapsed between the birth dates of two consecutive children. This calculation takes into account both the WHO recommended spacing of 24 months birth-to-pregnancy (BTP) interval and the typical 9 months duration of pregnancy or the potential impact of family planning methods on the timing of subsequent births, resulting to 33 months interbirth interval12,25.

Independent variables

The independent variables comprised the sociodemographic characteristics of the women, including age, education level, religion, wealth index, employment status, marital status, place of residence, and region.

The survival status of the previous child was not available in the NDHS 2018 dataset used for this analysis, and therefore could not be examined.

The wealth index used in this study is a composite measure developed by the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) Program, derived using principal component analysis (PCA). Household assets such as ownership of durable goods, housing quality, and access to utilities were included in the calculation. The index was divided into five quintiles: poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and richest, representing relative wealth levels within the population.

Data processing and management

The data was processed and analysed using STATA 17 statistical software. To account for the complex survey design, sampling weights, primary sampling units (PSU), and strata were applied in the analysis.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and cross-tabulations were employed to characterize the study population and identify patterns of birth intervals across various sociodemographic factors. To visualize the prevalence of SBI across different regions of Nigeria, both a bar chart and a geographical map were utilized, illustrating the proportion of SBI by geopolitical regions of Nigeria. Bivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate the relationship between birth intervals and individual sociodemographic factors. Following this initial analysis, a multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to identify the sociodemographic factors that significantly influence SBI across the regions of Nigeria. The results from the bivariate analysis were reported as crude odds ratios (COR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), using a significance threshold of 0.05. In the multivariable analysis, adjusted odds ratios (AOR) were calculated along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals, maintaining the same significance level.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

The study analysed a total of 25,280 women of reproductive age (15–49 years) from the NDHS (Table 1). The majority of the women were aged 25–29 years (20%), closely followed by those aged 30–34 (20%) and 35–39 (19%). Most of the women had no formal education (45%), while 29% had completed secondary education, and only 8% had higher education. Regarding religion, 58% of the women were Muslims, while 41% were Christians. In terms of marital status, 90% of the women were married, and 3% lived with a partner. Concerning wealth status, which was classified into quintiles using the DHS composite measure, the distribution revealed that 21% of women were classified as poorest while 18% as richest. In terms of residence approximately 42% of women lived in urban areas, while 58% resided in rural areas. In the distribution by region, 33% were from the North West, followed by the North East (17%), and North Central (14%) regions.

Prevalence and regional disparities of short birth interval

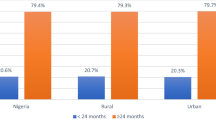

The highest prevalence of SBI was recorded in the South East (55.3%), followed by the North West (52.2%) and North East (52.0%). The South West region had the lowest prevalence, with 38.4% of women reporting SBI. These regional disparities were visualized in the map of Nigeria (Fig. 1), which illustrates the geographic variation in SBI across the six geopolitical zones.

Map of geopolitical regions in nigeria showing prevalence of short birth intervals. the map was generated using python (version 3.9) and the GeoPandas library (version 0.14.4; https://geopandas.org/). Geographical boundaries were sourced from GADM (Global Administrative Areas) shapefiles for Nigeria (https://gadm.org/).

Bivariate analysis of factors associated with short birth interval

The bivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 2) showed significant associations between SBI and various sociodemographic factors. Age was significantly associated with birth interval, with older women (45–49 years) being 3.40 times more likely to experience an optimal birth interval (COR = 3.40, 95% CI: 2.44–4.74, p < 0.001) compared to younger women aged 15–19 years. Higher education was not a significant factor for SBI (OR = 1.03, p = 0.59), while other educational levels were significant, as women with primary and secondary education had higher odds of experiencing an optimal BI (OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.12–1.32, p < 0.001; OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.03–1.19, p = 0.01) compared to those with no formal education. Marital status was not a significant factor, while religion was significant. Muslim women were slightly less likely to have an optimal birth interval than Christian women (COR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.81–0.92, p < 0.001). In terms of wealth, women in the richest quintile had significantly higher odds of experiencing an optimal BI (COR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.12–1.38, p < 0.001) compared to those in the poorest quintile.

Multivariable analysis of sociodemographic factors associated with short birth interval

After adjusting for potential confounders, the multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 3) revealed age to be a significant predictor of SBI, with odds increasing consistently across older age groups. Women aged 45–49 years were 3.23 times more likely to experience an optimal BI compared to those aged 15–19 years (AOR = 3.23, 95% CI: 2.32–4.50, p < 0.001). Significant increases were also observed among women aged 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, and 40–44, indicating a progressive age-related pattern. Educational attainment showed a protective effect, with women who had higher education being less likely to report SBI (AOR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.74–0.99, p = 0.03) compared to those with no formal education. While not statistically significant, wealth was associated with lower odds of SBI among women from the richest households (AOR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.87–1.13, p = 0.90) compared to those in the poorest quintile. Regional disparities were observed. Compared to women in the North Central region, those in the South East had significantly lower odds of optimal BI (AOR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.59–0.75, p < 0.001), while those in the South West had significantly higher odds (AOR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.23–1.57, p < 0.001). Women in the North East (AOR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.84–1.03, p = 0.192), North West (AOR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.85–1.04, p = 0.242), and South South (AOR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.84–1.07, p = 0.412) did not exhibit significant differences in odds compared to the North Central region.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal significant regional and sociodemographic disparities in SBI prevalence in Nigeria, highlighting the complex interplay between education, wealth, age, and geographic location. The overall prevalence of SBI remains high, with 51.6% of women experiencing SBI. There were notable regional variations, with the South East (55.3%), North West (52.2%), and North East (52.0%) regions having the highest prevalence. In contrast, the South West had the lowest prevalence at 38.4%. These regional differences underscore the influence of underlying cultural, economic, and healthcare access issues on birth spacing practices26. These findings are consistent with previous research, which has demonstrated the significant role of socioeconomic and regional disparities in shaping birth intervals in low and middle-income countries27,28.

Education was found to be a significant predictor of birth interval length. Women with higher education were less likely to experience SBI, with those holding a higher education degree having an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.74–0.99, p = 0.03) compared to women with no formal education. This finding aligns with existing literature, which emphasizes the role of education in promoting health-seeking behaviors and empowering women to make informed reproductive health decisions29,30,31. Educated women are more likely to be aware of and use modern contraceptive methods, which are essential for maintaining optimal birth intervals30. The inverse relationship between education and SBI underscores the need for continued efforts to improve women’s access to education, particularly in regions where educational attainment remains low.

Wealth did not show a statistically significant association with SBI (e.g., AOR for the richest quintile = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.87–1.13, p = 0.90). This finding suggests that, after adjusting for other sociodemographic factors, wealth alone may not be a strong determinant of SBI in the Nigerian context. This contrasts with the bivariate analysis, where women from the poorest households had higher odds of SBI. While wealth is often considered a critical factor in determining access to family planning and healthcare29,30, the findings from this study indicate that its influence may be less pronounced when other sociodemographic factors are considered. Future studies should explore how wealth interacts with education and healthcare access to influence birth intervals.

The study also identified significant age-related disparities in SBI, which indicates that all age groups above 19 years had higher odds of not experiencing SBI compared to women aged 15–19 years, with a progressive increase in odds as age advanced. Women aged 45–49 years had 3.23 times higher odds of experiencing optimal BI (AOR = 3.23, 95% CI: 2.32–4.50, p < 0.001) compared to women aged 15–19 years. This trend may be explained by several factors. Older women, particularly those aged 35 and above, may face societal or personal pressures to complete their desired family size as they approach the end of their reproductive years. This trend may be explained by several factors. Older women, particularly those aged 35 and above, may have already achieved their desired family size or face different life circumstances that lead them to consciously space their births more optimally. This behavior might align with findings from previous studies in sub-Saharan Africa, where women, once they achieve their ideal family size, prioritize health and well-being, which can include longer birth intervals31. Additionally, age-related declines in fertility might naturally result in longer intervals between pregnancies due to increased time to conception or fewer pregnancies overall, contributing to a higher proportion of optimal birth intervals among those who do conceive (32).

Interestingly, marital status did not show a significant association with SBI in the multivariable analysis, a finding that contrasts with existing literature that often highlights marital status as a determinant of reproductive behaviors26. While marital status has been linked to access to family planning services and decision-making autonomy in some studies, the lack of association observed in this study could suggest that other factors, such as age, education, or socioeconomic status, may play a more critical role in shaping birth spacing practices in the Nigerian context25,28.

Regional disparities in SBI were particularly pronounced, with the highest prevalence observed in the South East, North West, and North East regions. The high prevalence of SBI in the northern regions is consistent with prior studies, which attribute it to limited healthcare access, traditional values discouraging contraceptive use, and socio-economic disparities. Conversely, the unexpectedly high prevalence in the South East, despite higher education and wealth levels, may reflect cultural norms prioritizing larger family sizes or limited uptake of contraceptive services9,27. Despite its higher levels of education and wealth, the South East had a surprisingly high SBI prevalence (55.3%). This may be attributed to cultural practices that prioritize larger family sizes or social norms that discourage the use of contraceptives, even among educated and wealthier women19. Understanding the specific cultural factors driving this phenomenon in the South East is critical for developing targeted family planning interventions in the region.

Implications and recommendations

The findings of this study highlight significant regional and sociodemographic disparities in short birth interval (SBI) prevalence across Nigeria. The unexpectedly high prevalence of SBI in the South East for example, despite higher education and wealth levels, suggests that cultural norms and access to family planning services may play a greater role than previously understood. These disparities have serious implications for maternal and child health, as closely spaced pregnancies increase the risk of adverse health outcomes.

To address these challenges, targeted interventions should focus on expanding access to family planning services, particularly in regions with high SBI prevalence. Efforts must be made to promote educational and awareness programs that address cultural and religious misconceptions surrounding birth spacing, especially in the South East and northern regions. Additionally, strengthening healthcare infrastructure in rural and underserved areas is crucial for improving access to contraceptive methods. Policymakers should prioritize integrating family planning services into existing healthcare systems to ensure equitable access across all regions of Nigeria. This integration can help mitigate economic barriers that prevent women from utilizing family planning resources effectively. By fostering an environment that supports informed reproductive choices through education and accessible healthcare, stakeholders can work towards reducing the prevalence of short birth intervals and enhancing overall maternal and child health outcomes throughout Nigeria.

Conclusion

This study reveals significant regional and sociodemographic disparities in the prevalence of SBI in Nigeria. Women from the South East, North West, and North East regions exhibited the highest rates of SBI, with wealth and education emerging as critical determinants of birth spacing practices. Notably, despite higher socioeconomic status, the South East region had displayed unexpectedly high SBI prevalence, suggesting that cultural norms may significantly influence birth spacing decisions. Interventions targeting education, economic barriers, and cultural norms are essential for reducing the prevalence of SBI and improving maternal and child health outcomes across Nigeria.

Limitations

This study’s cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw strong causal inferences, as data on exposures and outcomes were collected simultaneously, making it difficult to establish temporal sequence and causality. While this design is valuable for identifying associations and describing patterns, it cannot definitively determine cause-and-effect relationships between sociodemographic factors and short birth intervals (SBI). The analysis focused primarily on sociodemographic and regional variables, deliberately excluding other important determinants such as antenatal care, postnatal care, and survival status of the previous child, which have been explored in other studies within the Nigerian context. This focus provides targeted insights but may offer an incomplete picture of all factors influencing SBI. Additionally, reliance on self-reported data from the NDHS introduces the possibility of recall bias, potentially affecting the accuracy of reported birth intervals. Recognizing these limitations, future research incorporating longitudinal designs and a broader range of clinical and healthcare variables would enhance understanding of the multifaceted determinants of SBI.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program repository, accessible at https://dhsprogram.com/Data/. This manuscript presents secondary analyses of this publicly available dataset.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- COR:

-

Crude Odds Ratio

- IR:

-

Individual Record

- LMIC:

-

Low and Middle-Income Countries

- NDHS:

-

Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey

- PSU:

-

Primary Sampling Unit

- SBI:

-

Short Birth Interval

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Hutcheon, J. A., Nelson, H. D., Stidd, R., Moskosky, S. & Ahrens, K. A. Short interpregnancy intervals and adverse maternal outcomes in high-resource settings: an updated systematic review. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 33 (1), O48–59 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Short interpregnancy interval can lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes: A meta-analysis. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 922053 (2022).

The World Health Organization (WHO). recommends a minimum of 24 months between consecutive births to allow sufficient time for maternal recovery and to reduce the risks of these negative outcomes - Google Search [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.google.com/search?q=The+World+Health+Organization+%28WHO%29+recommends+a+minimum+of+24+months+between+consecutive+births+to+allow+sufficient+time+for+maternal+recovery+and+to+reduce+the+risks+of+these+negative+outcomes+&sca_esv=a132f53bdbf2e8af&sca_upv=1&sxsrf=ADLYWIIZC2pv3E0ko1_k-3ZjDRuSV_hfyg%3A1727136955022&ei=uwTyZvmMAc6FhbIPmL28oAQ&ved=0ahUKEwi51rrFptqIAxXOQkEAHZgeD0QQ4dUDCA8&uact=5&oq=The+World+Health+Organization+%28WHO%29+recommends+a+minimum+of+24+months+between+consecutive+births+to+allow+sufficient+time+for+maternal+recovery+and+to+reduce+the+risks+of+these+negative+outcomes+&gs_lp=Egxnd3Mtd2l6LXNlcnAiwwFUaGUgV29ybGQgSGVhbHRoIE9yZ2FuaXphdGlvbiAoV0hPKSByZWNvbW1lbmRzIGEgbWluaW11bSBvZiAyNCBtb250aHMgYmV0d2VlbiBjb25zZWN1dGl2ZSBiaXJ0aHMgdG8gYWxsb3cgc3VmZmljaWVudCB0aW1lIGZvciBtYXRlcm5hbCByZWNvdmVyeSBhbmQgdG8gcmVkdWNlIHRoZSByaXNrcyBvZiB0aGVzZSBuZWdhdGl2ZSBvdXRjb21lcyAyChAAGLADGNYEGEcyChAAGLADGNYEGEcyChAAGLADGNYEGEcyChAAGLADGNYEGEcyChAAGLADGNYEGEcyChAAGLADGNYEGEcyChAAGLADGNYEGEcyChAAGLADGNYEGEdIsxhQ7hNY7hNwAXgBkAEAmAEAoAEAqgEAuAEDyAEA-AEC-AEBmAIBoAILmAMAiAYBkAYIkgcBMaAHAA&sclient=gws-wiz-serp

Islam, M. Z., Islam, M. M., Rahman, M. M. & Khan MdN. Exploring hot spots of short birth intervals and associated factors using a nationally representative survey in Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 12, 9551 (2022).

Ajegbile, M. L. Closing the gap in maternal health access and quality through targeted investments in low-resource settings. J. Global Health Rep. 7, e2023070 (2023).

Npc, N. P. C. ICF. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018 - Final Report. 2019 Oct 1 [cited 2024 Aug 9]; Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr359-dhs-final-reports.cfm

Islam, M. Z., Billah, A., Islam, M. M., Rahman, M. & Khan, N. Negative effects of short birth interval on child mortality in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob Health 12, 04070 (2022).

Abubakar, I. et al. The lancet Nigeria commission: investing in health and the future of the Nation. Lancet 399 (10330), 1155–1200 (2022).

Ajayi, A. I. & Somefun, O. D. Patterns and determinants of short and long birth intervals among women in selected sub-Saharan African countries. Med. (Baltim). 99 (19), e20118 (2020).

Wegbom, A. I. et al. Rural–urban disparities in birth interval among women of reproductive age in Nigeria. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 17488 (2022).

Aychiluhm, S. B., Tadesse, A. W., Mare, K. U., Abdu, M. & Ketema, A. A multilevel analysis of short birth interval and its determinants among reproductive age women in developing regions of Ethiopia. Plos One. 15 (8), e0237602 (2020).

Belachew, T. B., Asmamaw, D. B. & Negash, W. D. Short birth interval and its predictors among reproductive age women in high fertility countries in sub-Saharan africa: a multilevel analysis of recent demographic and health surveys. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 23 (1), 81 (2023).

Bintabara, D. & Mwampagatwa, I. Socioeconomic inequalities in maternal healthcare utilization: an analysis of the interaction between wealth status and education, a population-based surveys in Tanzania. PLOS Glob Public. Health. 3 (6), e0002006 (2023).

Weitzman, A. The effects of women’s education on maternal health: evidence from Peru. Soc. Sci. Med. 180, 1–9 (2017).

Mutua, M. K. et al. Wealth-related inequalities in demand for family planning satisfied among married and unmarried adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa. Reprod. Health. 18 (S1), 116 (2021).

Orji, A., Obochi, C. O., Ogbuabor, J. E., Anthony-Orji, O. I. & Okoro, C. A. Analysis of household wealth and child healthcare utilization in Nigeria. J. Knowl. Econ. 15 (1), 547–562 (2024).

Sampson, S. et al. Addressing barriers to accessing family planning services using mobile technology intervention among internally displaced persons in abuja, Nigeria. AJOG Glob Rep. 3 (3), 100250 (2023).

Adedini, S. A., Odimegwu, C., Bamiwuye, O., Fadeyibi, O. & Wet, N. D. Barriers to accessing health care in nigeria: implications for child survival. Glob Health Action. 7 https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23499 (2014).

Namasivayam, A., Schluter, P. J., Namutamba, S. & Lovell, S. Understanding the contextual and cultural influences on women’s modern contraceptive use in East uganda: A qualitative study. PLOS Glob Public. Health. 2 (8), e0000545 (2022).

Fadeyibi, O. et al. Household structure and contraceptive use in Nigeria. Front. Glob Womens Health. 3, 821178 (2022).

Lawani, L. O. et al. Interpregnancy interval after a miscarriage and obstetric outcomes in the subsequent pregnancy in a low-income setting, nigeria: A cohort study. SAGE Open. Med. 10, 20503121221105589 (2022).

Elegbua, C., Raji, H., Biliaminu, S., Ezeoke, G. & Adeniran, A. Effect of inter-pregnancy interval on serum ferritin, haematocrit and pregnancy outcome in ilorin, Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 23 (1), 326–337 (2023).

Sarmiento, I. et al. Causes of short birth interval (kunika) in Bauchi state, nigeria: systematizing local knowledge with fuzzy cognitive mapping. Reprod. Health. 18 (1), 74 (2021).

Ansari, U. et al. Kunika women are always sick: views from community focus groups on short birth interval (kunika) in Bauchi state, Northern Nigeria. BMC Womens Health. 20 (1), 113 (2020).

Tesema, G. A., Worku, M. G. & Teshale, A. B. Duration of birth interval and its predictors among reproductive-age women in ethiopia: Gompertz gamma shared frailty modeling. PLoS One. 16 (2), e0247091 (2021).

Afolabi, R. F. et al. Regional differences in the utilisation of antenatal care and skilled birth attendant services during the COVID-19 pandemic in nigeria: an interrupted time series analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 8 (10), e012464 (2023).

Pimentel, J. et al. Factors associated with short birth interval in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 20, 156 (2020).

Vedeler, C. et al. Women’s negative childbirth experiences and socioeconomic factors: results from the babies born better survey. Sex. Reproductive Healthc. 36, 100850 (2023).

Mkhailef Hawi Al-tameemi, M., Bahmanpour, K., Mohamadi-Bolbanabad, A., Moradi, Y. & Moradi, G. Insights into determinants of health-seeking behavior: a cross-sectional investigation in the Iraqi context. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1367088 (2024).

Ahmed, S., Creanga, A. A., Gillespie, D. G. & Tsui, A. O. Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PloS One. 5 (6), e11190 (2010).

Muyunda, B., Makasa, M., Jacobs, C., Musonda, P. & Michelo, C. Higher educational attainment associated with optimal antenatal care visits among childbearing women in Zambia. Front. Public. Health. 4, 127 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to the DHS program that provided authorization to use the dataset for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS was instrumental in the conceptualization, study design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data. JS also led the drafting of the initial manuscript. YAA, AUF, AMU, LB, WMT, DMT, SH, and ROY made substantial contributions to manuscript revisions, editing and validation. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The NDHS 2018 data are publicly available and anonymized. Authorization to use the data was obtained through the DHS program’s online request platform. Since the data were secondary and de-identified, no further ethical approval was required for this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sani, J., Arigbede, Y.A., Usman, A.F. et al. Assessing regional disparities and sociodemographic influences on short birth intervals (SBI) among reproductive-age women in Nigeria. Sci Rep 15, 34493 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13903-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13903-6