Abstract

Accurate estimation of induced abortion rates in legally restrictive contexts remains a challenge because fear of prosecution and stigma hinder truthful reporting among women. We examined induced abortion reporting accuracy by assessing the agreement between women’s self-reports of induced abortion and provider diagnosis of women’s abortions. We used data from three prospective morbidity surveys conducted in health facilities in Kenya (surveyed in 2022), Liberia (surveyed in 2021), and Sierra Leone (surveyed in 2021). The data were collected from post-abortion care (PAC) patients and healthcare providers in health facilities across Liberia (137 facilities), Sierra Leone (294 facilities), and Kenya (74 facilities). The data collectors were trained enumerators who were health providers and mostly females. Data analysis involved Kappa statistics to assess the agreement between PAC patients’ self-reports and provider diagnosis regarding whether the abortion for which women sought PAC were induced or spontaneous, accounting for interviewer and respondent socio-demographic characteristics. Overall, 1888 pairs of PAC patient and provider prospective morbidity survey interviews were completed: 965 (Kenya), 401 (Liberia), and 522 (Sierra Leone). Fewer women (26.2% in Liberia, 28.5% in Kenya, and 28.7% in Sierra Leone) self-reported induced abortions compared to the provider diagnoses (Kenya, 42.3%; 41.3% in Liberia; 43.5% in Sierra Leone). Across the three countries, there was a 13.8–15.2% difference in the proportions of induced abortions based on women’s self-reports and provider diagnoses. In cases where providers reported induced abortions while patients indicated miscarriages, 23% of such cases had clinical evidence of induction (e.g., presence of foreign bodies in the genital tract or signs of trauma in the cervix), whereas 77% did not have any recorded symptoms. Interviews conducted by males showed substantial to almost perfect agreement (κ = 0.73). The level of agreement between women’s self-report and provider diagnosis was substantially greater among women with a secondary or tertiary education compared to those with primary education (κ = 0.68 vs. κ = 0.67). The agreement levels did not vary significantly by age and marital status. Direct methods for estimating the incidence of induced abortion are unlikely to generate accurate data because women underreport, and providers may misdiagnose induced abortions. Researchers should acknowledge the limitations of direct abortion estimation methods and carefully recruit and train interviewers to minimize biases and enhance reporting accuracy. We emphasize combining indirect methods with direct methods to improve the reliability and precision of induced abortion estimates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Abortion elicits varied emotions and opinions worldwide depending on individual and societal beliefs and norms. These opinions can range from very liberal, meaning that there should be few or no legal restrictions on women’s ability to access safe abortion care, to very conservative, where abortion should never be allowed or only under extreme circumstances1. Most countries have attempted to use legislation to regulate abortions, with abortion laws and policies varying in restrictiveness from country to country. Most high-income countries have more liberal laws positioning abortion as a reproductive rights issue and as healthcare, where women are empowered to choose the trajectory of their pregnancies, especially when they have unintended pregnancies2. In Africa, only five countries allow abortions on request (Tunisia, Benin, Guinea, Mozambique, South Africa) and only two countries allow abortions on broad social and economic reasons (Ethiopia and Zambia). However, the majority of African countries only allow abortions under a minimal set of conditions, including to preserve the health or life of a pregnant woman3. The abortion legal landscape reflects the conservative posture of many communities, limiting the individual freedom to choose a course of action for unintended pregnancies2,4. Similarly, abortion stigma is highly pervasive, especially in Africa, and women known to have sought or those seeking abortion services are exposed to stigma and social exclusion within their communities5.

While data on abortion incidence is very critical for policy and programming, accurate measurement of the incidence of induced abortion is challenging6. Some nationally representative household surveys (e.g., Demographic and Health Survey)7 have included questions on abortion, but these grossly underestimate abortion occurrence and have proven unreliable, especially in contexts where abortion is highly restricted and stigmatized8,9. Evidence is consistent on the influence of social desirability bias, wherein survey respondents tend to under-report socially undesirable behavior and overreport socially desirable aspects9,10. Women often under-report or misreport induced abortions as miscarriages, leading to an underestimation of induced abortions10,11,12,13.

While much of the evidence on abortion underreporting has come from questions added to large-scale or nationally representative household surveys11,14, it is also possible that underreporting occurs when women present for post-abortion care (PAC). Evidence has shown that due to the restrictions in access to safe abortion, women initiate abortions away from health facilities and have them completed at the health facility as PAC15. For example, in a Zambian study, over a third of women had initiated their abortion before arriving at the health facility15. Consequently, for fear of the law and harassment from law enforcers, and to shield themselves from stigma, women seeking PAC have been cited to report induced abortions as spontaneous8,16. Notably, the persons posing the questions, the way questions are asked, the sequencing of the questions, and women’s relationship with the interviewer also have been found to influence women’s responses14,17.

Audits of service data, such as national health information systems that collate facility data on several indicators, including abortion, offer an alternative option to measure abortions18. However, such records are also unreliable: record keeping is rudimentary, mostly manual, and incomplete–some patient records go missing, and some care is never recorded in a formal health record19,20. As such, health facility records cannot produce reliable estimates of induced abortion21. When records do exist, information on abortion status is often unreliable; because abortion is illegal, health caregivers may intentionally conceal induced abortions by recording them as spontaneous abortions and PAC10. Further, providers are often unable to distinguish between induced and spontaneous abortion due to similarities in their clinical presentations22.

For this study, we examined induced abortion underreporting by assessing the extent of agreement between women’s self-reports of induced abortion and provider diagnoses on whether women’s abortions were spontaneous or induced across three sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries (Kenya, Liberia, and Sierra Leone). Findings from this study will contribute to improving the accuracy of abortion incidence estimation, especially in the African context where abortion legal restrictions and stigma are common.

Methods

Data and procedures

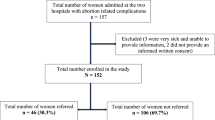

We used data from cross-sectional prospective morbidity surveys of women presenting for post-abortion care in Kenya (2022), Liberia (2021)23, and Sierra Leone (2021)24. The prospective morbidity surveys (PMSs) involved continuously observing a sample of health facilities for 30 days prospectively, recruiting and interviewing women and girls as they presented for PAC at these facilities. The PMS had two questionnaires: the patient and provider sections. In this paper, we included data for which both patient and provider interviews were completed. In Liberia and Sierra Leone, we undertook fieldwork between August and November 2021, while in Kenya, the survey was between February and May 2022. We used nationally representative samples of health facilities expected (by the facility level) to provide PAC in Liberia (n = 137) and Sierra Leone (n = 294). In Kenya, we randomly selected facilities in six of the 47 counties (n = 74), which we observed for 90 continuous days. The sample and length of observation for the survey in Kenya differed because the study was part of a larger intervention evaluation, while in Liberia and Sierra Leone, the surveys were specifically conducted to examine the severity of post-abortion complications. The intervention in Kenya was focused on improving medication abortion services in communities through the training of community pharmacists and the provision of medication abortion products to those service points.

Study participants

Respondents were women and girls presenting for PAC during the study fielding periods. In the selected facilities, all women and girls who presented with complications resulting from abortion were eligible, irrespective of age and whether the abortion was spontaneous (miscarriage) or induced. All missed, inevitable, incomplete, complete, or septic abortions were included, notwithstanding the degree of the severity of the complication. We excluded women who presented with ectopic and molar pregnancies and threatened abortion. Women with threatened abortions (pregnancies that do not ultimately end in abortions, perhaps due to an intervention) were regarded as not having had an induced abortion. Ectopic and molar pregnancies were excluded because they require special procedures and are not treated as PAC. In the analysis, we excluded women who refused to participate or could not respond, were referred to another facility, died, or completed only part of the survey.

Data collectors

In Sierra Leone and Kenya, all interviewers were healthcare workers at the facility where the interviews were conducted. In some cases, they were also the individuals who provided or participated in the patients’ care. In Liberia, interviewers were healthcare providers who did not work in the facility where the women they interviewed received care. We conducted an intensive five-day training for all data collectors that focused on the study protocol, eligibility for inclusion in the study, selection procedure, ethical consideration (e.g., informed consenting, confidentiality, and respect for the participants), interviewing skills, value clarification and attitude transformation, and the use of Android-based devices in data collection.

Measures and indicators

We collected data using patient questionnaires previously used across Africa and, more recently, Zimbabwe25. In all surveys, women/girls responded to three key questions: (1) “Before the pregnancy that brought you to the health facility today, how many induced abortions have you had?” (2) “Do you know anyone (woman or girl) who has done something to end their pregnancy?” (3) “For the pregnancy that brought you to the hospital to seek PAC, did you or someone else do something to interfere with its continuation?”. We coded the responses to question 1 as either “0” or “at least 1”. For questions 2 and 3, the responses were “yes” or “no”; we re-coded “yes” to question 2 as “know someone who has had an induced abortion” and “no” to represent “does not know anyone who has had an induced abortion”. Yes or no in question 3 were re-coded as “induced abortion” or “spontaneous abortion”, respectively. We also collected data on women’s socio-demographic characteristics (age, residence, marital status, religious affiliations, and education), and reproductive health characteristics (including previous child births, previous abortions, and knowledge of someone who has had an abortion).

We used a questionnaire previously used in Zimbabwe25 for the provider interview, which collects data on clinical presentations, diagnosis, treatment, contraceptive provision, and referral. The question of interest in this paper was: “Based on your overall assessment of the client and your clinical examination findings, how would you classify the patient’s abortion?”. Using WHO’s (1986) guidance, the response categories were “certainly induced”, “probably induced”, “possibly induced”, and “spontaneous miscarriage”. We reclassified the responses into two categories: “induced” and “spontaneous”, with certainly induced, probably induced, and possibly induced grouped into “induced abortion”.

Additionally, the provider questionnaire captured details on clinical indicators, including the status of patient presentation, physical or digital examination details, diagnosis, treatment, other management approaches, and status of the patient at discharge/referral or death. Providers were asked whether there was the presence of foreign bodies in the genital tract and whether there were signs of trauma to the cervix, vagina, uterus, or intra-abdominal walls (yes/no). We also assessed the presence of physical injuries, including cervical tears, tenaculum bites of the cervix, mechanical injury to the uterus, intra-abdominal injury, and puncture of the cervix or vagina (yes/no). The presence of foreign bodies or mechanical injuries, or both, was considered clinical evidence of an induced abortion. We assessed the presence of these symptoms to check whether clinical signs supported the providers’ diagnoses. The analysis compared the level of agreement between the variable “presence of clinical evidence of induced abortion” with the provider diagnosis (“yes” to induced abortion) and the patient’s self-report (“yes” to inducing the abortion).

Data analysis

We compared women’s self-reports about their abortion (whether it was spontaneous or induced) to the providers’ diagnoses. We used Kappa statistics to compare women’s self-reports with providers’ diagnoses. We controlled for the effect of respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics, survey country (Kenya, Liberia, and Sierra Leone), and residence (rural vs. urban) to regress the odds of a woman reporting that they induced their current abortion. To do this, we computed the frequency and proportion of induced abortions from women’s self-reports and providers’ assessments as “self (+)”, “provider (+)”, “self (+) provider (+)”, “self (-) provider (+)”, “self (+) provider (-)”, and “self (-) provider (-)” where “+” implies “induced” and “-” for “spontaneous”. We do not have a gold standard (a reference point or indicator) because our objective is not to determine whether the provider or the patient is accurate. Instead, we described the level of agreement between providers and patients on induced abortions using observed agreement (overall agreement), chance agreement, positive agreement, and negative agreement, and Cohen’s kappa (κ) coefficients (with a 95% confidence interval – CI) to determine the agreement beyond chance between women’s self-reports and healthcare provider diagnosis26, only retaining cases for which self-reports and the provider assessment report were known.

Consistent with guidelines from previous literature on grading agreement, we interpret κ coefficients as poor (0.01–0.20), fair (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), substantial (0.61–0.80), and near/almost perfect (0.81–1.00)27. In R, we also used the kaphom::donnerhom function, which compares the null hypothesis of homogeneity to an alternative heterogeneity hypothesis28. We used the Donner29 Goodness of Fit to test the difference between the given κ statistics across the levels of respondents’ characteristics since, unlike other tests, it does not require the equal prevalence assumption for the samples from which the different κ statistics are obtained.

We also assessed for potential differences in agreement reliability within stratified groups (categories), including patient age (≤ 24 years vs. 25+), gender of the interviewer, and whether the interview was conducted by the same provider who cared for the woman. That is, we tested for equal sample distribution by evaluating whether the κ statistics from the subgroups were homogeneous to make inferences over a single κ statistic summarizing all the groups28,29.

In all the regression models, we multiplied imputed missing data using the mice function in R (Buuren et al., 2022). Statistical significance was set at a p-value < 0.05.

Results

The analysis involved 1888 respondents across the three countries (Kenya n = 965; Sierra Leone n = 522; Liberia n = 401). The mean age across the countries was 25 years (Table 1). Urban-rural distribution was roughly even in Kenya and Sierra Leone, while almost three-quarters of patients (72.6%) in Liberia reported living in an urban area.

Across the countries, more women were married or partnered (> 72%), and most participants in Kenya and Liberia were Christians (97.4% and 87.8%, respectively). In Sierra Leone, Muslims were the majority (63.0%). Regarding previous abortion history, a small proportion (12.1% overall) reported having a previous induced abortion, with larger proportions reported in Sierra Leone (19.9%) and Liberia (16.7%) than in Kenya (6.0%). On the other hand, more than a third (36.2%) overall reported knowing someone else who has ever had an induced abortion.

Table 2 displays provider assessments and respondent reports of the abortion status of the pregnancy for which the respondent was seeking PAC. Overall, smaller proportions of women reported that their abortion was induced (26.2%, Liberia; 28.5%, Kenya and 28.7%, Sierra Leone) compared to the proportions recorded from the provider diagnosis (41.3% Liberia, 42.3% Kenya, and 43.5% Sierra Leone).

Table 2 shows that overall, the difference between self-reported and provider assessment reports of induced abortion was statistically significant across the three countries at around 14–15% (14.3%, 95% CI: 11.3 to 17.4%).

Table 3 shows that there was substantial agreement between the patient self-reports and provider diagnosis regarding induced abortions (κ = 0.65, 95% CI 0.62–0.69; OA = 0.84). Patients and providers tended to come to the same conclusions on induced abortions, except in 15.0% of the cases. This level of agreement appears driven mainly by a relatively high negative-specific agreement (i.e., “No” to induced abortion) (56.4%).

We observed statistically significant differences (p = 0.009) in the estimates of κ across the countries (Kenya, κ = 0.71; Liberia, κ = 0.61; Sierra Leone, κ = 0.58). Overall, and across the three countries, we observed that women interviewed by female providers (female data collectors) had a moderate to substantial agreement (κ = 0.64) with the provider diagnosis compared to those interviewed by male providers (male data collectors) (κ = 0.73, substantial to almost perfect agreement). However, we did not find a statistically significant difference between the κ statistics, suggesting no discernible effect of the interviewer’s sex on the agreement between the patient self-report and provider diagnosis. Female interviewers constituted a larger sample (85.5%), implying less variation. The standard error (se(κ)) for female interviewers was 50% lower than that of male interviewers, which explains the difference and the lack of statistical significance.

By respondent’s age group, we did not find statistically significant differences by age. We found women and girls aged ≤ 24 years had a substantial agreement (κ = 0.65) with the provider’s diagnosis compared with those 25 + years, we graded as moderate to substantial (κ = 0.63). Similarly, stratified estimates of κ statistics by marital status were not statistically different.

Women who had either a secondary or tertiary education had greater levels of agreement (κ = 0.68 and κ = 0.67, respectively) compared with those with no education or primary level (κ = 0.54 and κ = 0.58, respectively). We also found a statistically significant difference in estimates of κ between women who reported knowing anyone who induced an abortion (κ = 0.70 vs. κ = 0.56, p < 0.001). Other variables included in this analysis had insignificant k values; therefore, the independent strata were deemed homogeneous.

Table 4 summarizes the clinical evidence supporting the provider’s diagnosis. Of the 496 cases with a positive agreement between self-reports and provider diagnosis, three–quarters (75.0%) were not based on recorded clinical signs and symptoms. Figure 1 shows no significant difference in the agreement between provider diagnoses and clinical evidence by survey country.

Discussion

Our analysis reveals a substantial level of agreement (k = 0.65) between women’s self-reports of induced abortion and provider diagnosis on whether women’s abortion was spontaneous or induced in Kenya, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Similar proportions of women across the three countries reported having induced their abortions (Liberia: 26.2%; Kenya: 28.5%; and Sierra Leone: 28.7%), which may be reflected in the broad similarity in abortion legal contexts across the three countries. Previous studies in Ghana reported similar proportions of self-reported induced abortions among women presenting with complications from pregnancy loss (17%)30, and a retrospective household survey reported about 20%31. However, the proportion of self-reported induced abortions in this study is likely an underestimate of the true proportion of PAC cases due to induced abortion; fewer women are likely to admit if they have had an induced abortion, mainly because abortion stigma is pervasive in the African contexts and those known to be seeking or to have had an abortion risk facing stigmatization and ostracization5, and also harassment from law enforcers16.

There was a 14.3% difference between self-reports and provider diagnoses of induced abortions in this study. This is likely attributed to the fact that women may deliberately misreport induced abortion as spontaneous miscarriages to evade exposure and stigma. This is consistent with findings from several studies across several geographies [e.g5,32. Given the cultural and social stigma associated with abortion, social desirability bias could also play a critical role in why women underreport induced abortion or report their induced abortions as miscarriages. As previously noted, abortion connotes moral, ethical, and religious conflicts for women and, in combination with social stigma and the legal context, forces women to fail or omit to report or misreport induced abortions as miscarriages in surveys and while presenting at health facilities with abortion-related complications10.

Another explanation for disagreement between providers and women’s reports is a deliberate misclassification or inaccurate diagnosis by providers. First, even providers can incorrectly document induced abortions as miscarriages. This could be because providers genuinely cannot distinguish induced abortions from miscarriages, given that the clinical indicators for spontaneous and induced abortions are similar22. Second, providers may deliberately document induced abortions as spontaneous to limit the magnitude of abortion cases they handle or to protect abortion seekers and providers. During fieldworker training in Sierra Leone, providers noted the variety of nomenclatures they use in medical records (e.g., attempted menorrhea) to navigate the sensitivities around abortion and abortion care.

The disparities between the provider diagnosis and women’s self-reports also point to the extraordinary challenges that abortion research and researchers face in contexts where laws are restrictive10. Due to these challenges, the reliability of abortion estimates is often challenged during policy engagements, and with abortion opponents being vocal in criticizing the methods of abortion estimation.

It is pertinent to point out that respondents interviewed by men had near-perfect agreement in their self-reported induced abortion and the provider’s diagnosis. We would have used an all-female team of interviewers if not for the fact that we used healthcare facility staff. As such, we had a mix of male and female interviewers. Having male and female interviewers provided the opportunity to examine the effects of the interviewer’s sex on induced abortion reporting. This finding offers insights into when males interview females about sensitive reproductive health matters and when providers are also interviewers, as it has been long established that interviewer effects influence abortion reporting14,17. Even so, this finding contradicts what would have been the expectation that women may be hesitant to disclose their experiences to male interviewers, as they may perceive them as judgmental or unsympathetic. Nonetheless, this deviation may be explained by the fact that our male interviewers were healthcare providers whom the women trust. Additionally, before data collection, the providers were trained and encouraged to be respectful and sensitive to the women participating in the study. Granted, the sample of male interviewers is not substantially large enough to warrant a definite pronouncement that male interviewers/providers generate more open and honest responses from female respondents in matters of sexual and reproductive health. This requires further testing with a larger pool of male and female interviewers and a larger sample of respondents.

Study limitations

A key limitation of relying solely on clinical signs to diagnose induced abortions is that such an approach primarily captures procedures involving mechanical or intrusive methods, such as surgical abortions, crude and unsafe techniques. In some cases, it also applied to medication abortions where products inserted vaginally have remained undissolved as of the time of examination. These signs, including the presence of foreign bodies in the vagina, uterus, or abdomen, and mechanical injuries, offer some evidence of induced abortion. However, these may be inadequate for detecting medication abortion methods. Furthermore, this approach overlooks critical contextual information obtained during patient history-taking. Providers may gather diagnostic insights through history-taking, yet our questionnaire did not ask whether women disclosed inducing the abortion, as recommended by classification guidelines (e.g33. It is also possible that the provider who took the patient’s history was not the same individual who made the clinical diagnosis, creating further gaps. These shortcomings may have led to misclassification biases previously noted by Menezes et al., including mistaking miscarriages with complications for induced abortions, or categorizing safe induced abortions as spontaneous. Our data support this concern as providers misclassified a proportion of women who reported inducing their abortions as having spontaneous abortions based on clinical signs alone. Also, providers may be overly sensitized to the possibility of induced abortion and patient misrepresentation of the nature of their abortions, making them more inclined to classify any abortion as induced, even without firm clinical evidence, further complicating the reliability of diagnosis. Finally, some study design differences across the three countries may have affected the results. For example, in Kenya, the data collection lasted 90 days compared to 30 in Liberia and Sierra Leone, leading to a significantly higher sample size. Further, the study design in Kenya did not allow for a nationally representative sample of health facilities, while the other two countries had nationally representative samples. In Sierra Leone, data collection was based on a paper questionnaire, while in Kenya and Liberia, the study team used electronic (tablet-based) data collection. In Sierra Leone and Kenya, all data collectors were providers who either cared for the patient or worked in the same facility, while in Liberia, the data collectors were healthcare providers but were not staff of the facilities where they were posted for data collection. With the standardization of the fieldwork training, the impact of these differences was mitigated.

Conclusion

This study concludes that utilizing direct methods of asking women in restrictive settings whether their abortions were induced or spontaneous leads to underreporting of induced abortion, as women may misrepresent induced abortion as spontaneous due to diverse reasons. Similarly, the study concludes that depending on providers to classify abortion based on clinical examination may lead to misclassification and consequently underreporting or overreporting of induced abortion. More work is needed to refine abortion measurement and account for the challenges highlighted in this study.

Data availability

All data and materials are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. Also, according to the APHRC (the organization hosting the datasets) policies, all deidentified datasets will be publicly available on the APHRC microdata portal after three years (https://aphrc.org/microdata-portal/).

Abbreviations

- ACRE:

-

Atlantic Center for Research and Evaluation

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- MA:

-

Medication abortion

- NACOSTI :

-

National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation

- PAC:

-

Post-Abortion Care

- PMS:

-

Prospective Morbidity Survey

- SE:

-

Standard Error

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- UL-PIRE :

-

University of Liberia’s Institutional Review Board

- WHO :

-

World Health Organization

References

Blystad, A. et al. The access paradox: abortion law, policy and practice in ethiopia, Tanzania and Zambia. Int. J. Equity Health. 18 (1), 126 (2019).

Lavelanet, A. F., Johnson, B. R. & Ganatra, B. Global abortion policies database: A descriptive analysis of the regulatory and policy environment related to abortion. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 62, 25–35 (2020).

Center for Reproductive Right. New York. (The World’s Abortion Law). (2016). Available from: https://reproductiverights.org/maps/worlds-abortion-laws/

Remez Mayall, singh. Global developments in laws on induced abortion: 2008–2019. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health. 46 (Supplement 1), 53 (2020).

Ushie, B. A. et al. Community perception of abortion, women who abort and abortifacients in Kisumu and Nairobi counties, Kenya. Bourgeois D, editor. PLOS ONE. ;14(12):e0226120. (2019).

Gerdts, C., Tunçalp, O., Johnston, H. & Ganatra, B. Measuring abortion-related mortality: challenges and opportunities. Reprod. Health. 12 (1), 87 (2015).

Fenta, S. M. et al. Pooled prevalence of induced abortion and associated factors among reproductive age women in sub-Saharan africa: a bayesian multilevel approach. Arch. Public. Health. 83 (1), 159 (2025).

Tennekoon, V. Counting unreported abortions: A binomial-thinned zero-inflated Poisson model. Demogr Res. 36, 41–72 (2017).

Keogh, S. C. et al. Estimating the incidence of abortion: a comparison of five approaches in Ghana. BMJ Glob Health. 5 (4), e002129 (2020).

Menezes, G. M. S., Aquino, E. M. L., Fonseca, S. C. & Domingues, R. M. S. M. Abortion and health in brazil: challenges to research within a context of illegality. Cad Saude Publica. 36 (Suppl 1(Suppl 1), e00197918 (2020).

MacQuarrie, K. L. D., William, W., Meijer-Irons, J. & Morse, A. Consistency of Reporting of Terminated Pregnancies in DHS Calendars. [Internet]. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF.; Report No.: 25. (2018). Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-mr25-methodological-reports.cfm

Lindberg, L. D., Maddow-Zimet, I., Mueller, J. & VandeVusse, A. Randomized experimental testing of new survey approaches to improve abortion reporting in the U nited S Tates. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health. 54 (4), 142–155 (2022).

Yan, T. & Tourangeau, R. Detecting underreporters of abortions and miscarriages in the National study of family growth, 2011–2015. PLOS ONE. 17 (8), e0271288 (2022).

Leone, T., Sochas, L. & Coast, E. Depends who’s asking: interviewer effects in demographic and health surveys abortion data. Demography 58 (1), 31–50 (2021).

Coast, E. & Murray, S. F. These things are dangerous: Understanding induced abortion trajectories in urban Zambia. Soc. Sci. Med. 153, 201–209 (2016).

Shellenberg, K. M. et al. Social stigma and disclosure about induced abortion: results from an exploratory study. Glob Public. Health. 6 (sup1), S111–S125 (2011).

Footman, K. Interviewer effects on abortion reporting: a multilevel analysis of household survey responses in Côte d’ivoire, Nigeria and rajasthan, India. BMJ Open. 11 (11), e047570 (2021).

Maïga, A. et al. Generating statistics from health facility data: the state of routine health information systems in Eastern and Southern Africa. BMJ Glob Health. 4 (5), e001849 (2019).

Dehnavieh, R. et al. The district health information system (DHIS2): A literature review and meta-synthesis of its strengths and operational challenges based on the experiences of 11 countries. Health Inf. Manag J. 48 (2), 62–75 (2019).

Hoxha, K., Hung, Y. W., Irwin, B. R. & Grépin, K. A. Understanding the challenges associated with the use of data from routine health information systems in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Health Inf. Manag J. 51 (3), 135–148 (2022).

Giorgio, M., Sully, E. & Chiu, D. W. An assessment of Third-Party reporting of close ties to measure sensitive behaviors: the confidante method to measure abortion incidence in Ethiopia and Uganda. Stud. Fam Plann. 52 (4), 513–538 (2021).

Singh, S., Prada, E. & Juarez, F. The Abortion Incidence Complications Method: a Quantitative Technique. Methodologies for Estimating Abortion Incidence and Abortion-related Morbidity: a Review71–98 (Guttmacher Institute, 2010).

Giorgio, M. M. et al. The severity and management of postabortion care complications in Liberia [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 15]. Available from: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-4757559/v1

Küng, S. et al. Abortion-related morbidity and mortality in Sierra leone: results from a 2021 cross-sectional study. BMC Public. Health. 25 (1), 1121 (2025).

Madziyire, M. G. et al. Severity and management of postabortion complications among women in zimbabwe, 2016: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 8 (2), e019658 (2018).

McHugh, M. L. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 22 (3), 276–282 (2012).

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33 (1), 159–174 (1977).

Albayrak, M., Turhan, K., Yavuz, Y. & Aydin Kasap, Z. Kaphom: an R package for testing the homogeneity of intra-class kappa statistics. Commun. Stat. - Simul. Comput. 49 (12), 3283–3298 (2020).

Donner, A., Eliasziw, M. & Klar, N. Testing the homogeneity of kappa statistics. Biometrics 52 (1), 176 (1996).

Schwandt, H. M. et al. A comparison of women with induced abortion, spontaneous abortion and ectopic pregnancy in Ghana. Contraception 84 (1), 87–93 (2011).

Baruwa, O. J., Amoateng, A. Y. & Biney, E. Induced abortion in ghana: prevalence and associated factors. J. Biosoc Sci. 54 (2), 257–268 (2022).

Desai, S., Lindberg, L. D., Maddow-Zimet, I. & Kost, K. The impact of abortion underreporting on pregnancy data and related research. Matern Child. Health J. 25 (8), 1187–1192 (2021).

World Health Organization. Protocol for hospital-based Descriptive Studies of Mortality, Morbidity Related To Induced Abortion (WHO, 1987). Report No.: WHO Project No. 86912.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Vekeh Donzo and Mohamed Koblo Kamara, who coordinated fieldwork in Liberia and Sierra Leone, respectively, and the field teams’ hard work and diligence in collecting the study data. We also thank all the respondents for participating.

Funding

The Liberia and Sierra Leone studies were supported by a grant from the African Regional Office of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida (Contribution No. 12103), to the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) under the Challenging the Politics of Social Exclusion project. A grant from the Children Investment Fund Foundation and a large anonymous donor supported the Kenya study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BU, KJ, and MG conceptualized the Liberia and Sierra studies and were primarily involved in the data collection. BU conceptualized the Kenya study and led the data collection activities. IA performed data cleaning and analysis guided by BU and MG. BU wrote the initial draft, and all authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved in Kenya by the AMREF Ethical and Scientific Review Committee (P658/2019), the University of Nairobi/Kenyatta National Hospital Ethical Board (IREC/2019/290), and Moi University Teaching and Referral Hospital (P643/07/2019), while the National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation provided the research authorization (NACOSTI/P/19/9256/32022). In Liberia, the protocol and study materials were reviewed and approved by the University of Liberia’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), also known as UL-PIRE (now the Atlantic Center for Research and Evaluation (ACRE) Institutional Review Board, Protocol #21-07-275). The Ethics and Scientific Committee, Ministry of Health, Sierra Leone, approved the study (no approval number assigned). In addition, all study procedures were conducted in accordance with guidelines and regulations for human subject research and as peculiar to each country. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants during the study. In Liberia, we interviewed the health providers only if the women/girls consented to their providers responding to our questionnaire. However, the requirement was not needed in Kenya and Sierra Leone.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants during the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ushie, B.A., Juma, K., Akuku, I. et al. Assessing induced abortion underreporting in restrictive settings using prospective morbidity surveys from Kenya, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Sci Rep 15, 28756 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14096-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14096-8