Abstract

Breastfeeding is widely recognized as the optimal form of infant nutrition; however, exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates remain low worldwide. Psychological factors such as maternal self-efficacy and satisfaction play a key role in breastfeeding success. This randomized controlled trial evaluated whether a mixed-reality educational strategy could improve maternal self-efficacy and breastfeeding satisfaction. A total of 58 pregnant women in their third trimester were randomly assigned to receive either mixed reality plus traditional counseling or traditional counseling alone. Breastfeeding self-efficacy and satisfaction were measured one week postpartum using validated instruments. No statistically significant differences were found between the groups in self-efficacy (mean scores 63.3 vs. 63.1) or satisfaction (133.5 vs. 134.0). However, both groups demonstrated remarkably high rates of exclusive breastfeeding during the first week of life (93.1%), far exceeding the national and global average. Although the mixed-reality intervention did not yield superior outcomes within the short follow-up period, the findings highlight the potential benefits of structured prenatal education in enhancing breastfeeding practices. This low-cost immersive approach may be particularly relevant in middle- and low-income settings. Further research with a larger sample size and extended follow-up is required to assess the long-term impact and broader applicability of mixed reality in maternal health education.

Clinical trial registration: https://ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06800521; registered on 30/01/2025).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pregnant women often experience fear and uncertainty regarding pregnancy, childbirth, motherhood, and breastfeeding1. While breastfeeding is a natural and instinctive act, it requires learning to master appropriate techniques and navigate its social, cultural, and psychological implications2. For newborns, breastfeeding represents the “gold standard” for nutrition, recognized by the United Nations as a fundamental right to be protected3. According to the World Health Organization and UNICEF, infants should be exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life, with continued breastfeeding alongside appropriate complementary foods for at least two years4. Breast milk is natural, sustainable, non-polluting, and renewable, aligning with Sustainable Development Goals and providing broad societal benefits5.

Despite its well-documented advantages, the global rate of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) remains suboptimal6,7. Only about 48% of infants under six months of age in low- and middle-income countries are exclusively breastfed, with the rate in Colombia being approximately 36%6,7,8. Efforts to address this gap have included health literacy strategies, with breastfeeding counseling being the most effective and widely implemented6. As recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1994, traditional counseling often prioritizes theoretical aspects over practical hands-on guidance6. Furthermore, it rarely incorporates modern technologies, resulting in limited emotional connection with the breastfeeding process9,10.

Adherence to EBF depends on a complex interplay of biological, social, cultural, familial, psychological, and healthcare-related factors11. Among these, psychological influences play a critical role, especially in today’s context where societal judgment and fear of infant health disproportionately affect women who do not breastfeed12. These insecurities are further exacerbated by aggressive formula marketing, which promotes sales at the expense of breastfeeding adherence6,13. Inadequate support or incorrect guidance from healthcare professionals also constitutes a significant barrier to successful EBF, whereas organized support provided by trained professionals or lay counselors has been shown to improve breastfeeding duration and exclusivity14.

Negative emotions such as insecurity and fear contribute to disinterest and demotivation, often leading to breastfeeding discontinuation15. In contrast, intrinsic motivation, driven by satisfaction and self-efficacy, defined as a mother’s confidence in her ability to breastfeed successfully, has the opposite effect of fostering sustained breastfeeding practices15. According to Self-Determination Theory, motivational factors are direct determinants of human behavior16. Mixed reality is a novel alternative17. Enriching cognitive experience with visual stimuli enhances attention and memory, thereby making educational messages more impactful17.

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of a mixed reality-based educational strategy compared to traditional breastfeeding counseling on maternal satisfaction and self-efficacy, two key determinants of breastfeeding success.

Methods

Study design

A non-inferiority randomized controlled trial was conducted at the Hospital Divino Salvador de Sopó, a second-level reference hospital in Sopó, Cundinamarca, between April and October 2024. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06800521; registered on 29/01/2025).

Ethical consideration

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidad de La Sabana (No. 130 on May 27, 2024), following national and international ethical guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki and Resolution 8430 of 1993 from the Colombian Ministry of Health. All participants provided written informed consent before their inclusion in the study. Consent was obtained during the prenatal care sessions to ensure that participants understood the objectives, procedures, and potential risks of the study. The confidentiality of participant data was maintained throughout the study. Data monitoring was overseen by the research team, and no interim analyses were conducted, as the sample size (58 participants) was completed in its entirety without deviation from the protocol.

Study population

Pregnant women in their third trimester of gestation, attending prenatal care in the municipality of Sopó, Cundinamarca, and expressing a desire to breastfeed, were included in the study. The participants were required to be over 18 years old, hemodynamically stable, and oriented. Newborns with congenital malformations, anatomical anomalies, or other conditions affecting breastfeeding were excluded, as were mother-child dyads with known contraindications for breastfeeding such as maternal HIV positivity, neoplastic treatments, or the need for NICU or ICU admission.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was the score obtained on the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form (BSES-SF) and the Maternal Breastfeeding Evaluation Scale (MBFES), both evaluated one week postpartum. The BSES-SF assesses maternal self-efficacy, with scores ranging from 14 to 70, with higher scores indicating greater confidence in breastfeeding. The MBFES measures maternal satisfaction with scores ranging from 30 to 150. This scale evaluates aspects such as maternal enjoyment of breastfeeding, perceived infant growth, and changes in maternal lifestyle.

Secondary outcomes included the percentage of neonates exclusively breastfed (EBF) during the first week of life and the types of food or supplements provided to neonates during this period. Feeding practices were categorized according to the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for exclusive breastfeeding, predominant breastfeeding, partial breastfeeding, and complementary feeding. The women were divided into exclusive and non-exclusive breastfeeding groups. Exclusive breastfeeding was defined as the provision of only human milk, with no additional liquids or solid foods, during the observation period.

To assess the primary outcomes, the BSES-SF and MBFES were self-administered by participants during a follow-up phone call conducted one week after birth. Responses to the BSES-SF were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “always,” while responses on the MBFES ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Adherence to exclusive breastfeeding was assessed during the same follow-up period using a structured survey.

Before recruitment, a pilot test was conducted to standardize the use of the scales and ensure consistency in the data collection process. This step aimed to minimize variability and enhance the reliability of the results.

Intervention

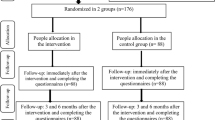

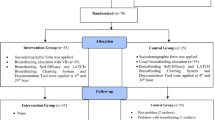

The mixed reality educational strategy was designed to enhance maternal self-efficacy and satisfaction with breastfeeding by combining traditional counseling with innovative tools. These tools included a mixed reality headset, silicone breast model, and infant doll to simulate proper latching and positioning techniques. The intervention also incorporated immersive video content of breastfeeding scenarios, displayed through the VaR VR Video Player application, and a neonatal simulator (infant mannequin) to enhance the realism and interactivity of the training (Fig. 1).

This strategy provided participants with a hands-on immersive learning experience aimed at improving their confidence and competence in breastfeeding. The sessions were integrated into maternity and paternity preparation courses conducted during the third trimester. Each session lasted approximately 60 min, allowing sufficient time for participants to practice with the tools under the guidance of trained healthcare professionals. Traditional counseling elements were included to address the physiological, emotional, and psychological aspects of breastfeeding, ensuring a comprehensive approach.

Participants in the control group received traditional breastfeeding counseling only. These sessions followed standard WHO-recommended protocols and provided theoretical and practical guidance, without the use of mixed-reality tools.

Procedures

A series of preparatory and operational steps were undertaken to ensure the successful implementation of the mixed-reality educational strategy. First, healthcare professionals, including nurses, nursing assistants, and general practitioners, underwent standardized training on the use of mixed reality and breastfeeding counseling techniques. The training included hands-on sessions to familiarize participants with the virtual reality headset, silicone breast model, infant doll, and immersive video content. This step aimed to standardize the delivery of the intervention and address potential gaps in knowledge, particularly for those who had not experienced parenthood.

Once the training was completed, the mixed reality strategy was incorporated into maternity and paternity preparation courses. Each session began with an overview of breastfeeding physiology and techniques, followed by a demonstration of the mixed-reality tools. Participants in the intervention group engaged in interactive sessions with real-time feedback from trained healthcare professionals, focusing on practical skills, such as proper latching and positioning.

Data collection was conducted following a standardized protocol to ensure consistency across all participants. Maternal self-efficacy and satisfaction were evaluated using the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form (BSES-SF) and the Maternal Breastfeeding Evaluation Scale (MBFES), respectively, during a follow-up phone call one week postpartum. In addition, exclusive breastfeeding rates were assessed using a structured survey.

Participants in the control group followed the same maternity and paternity preparation courses but were not exposed to mixed reality tools. Instead, these sessions emphasized traditional theoretical and practical counseling methods.

Randomization and blinding

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two study groups, intervention or control, using a computer-generated randomization sequence. The process employed permuted blocks of size four to ensure a balance between the groups and was centralized for consistency. Allocation numbers were concealed in opaque, sealed envelopes, which were sequentially opened by the study monitor immediately before the educational intervention and after the mothers consented to participate.

Owing to the nature of the educational strategy, which involved active engagement with mixed-reality tools, blinding was not feasible for participants. However, researchers analyzing the data were blinded to group allocation to minimize bias and ensure objectivity during statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was determined based on data from a study by Tseng et al.18 who evaluated the effect of an educational intervention on breastfeeding self-efficacy using the short version of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale (BSES-SF). A mean difference of 6.7 points with a standard deviation of 8.95 was reported. Assuming a confidence level of 95%, power of 80%, and an equal allocation ratio, 29 participants were required per group. This sample size was fully achieved, with no loss during follow-up.

Descriptive analyses were conducted to characterize the mother-child dyads in both study groups, considering biological, social, and demographic factors. Categorical variables are described using absolute and relative frequencies, whereas continuous variables are summarized using measures of central tendency, dispersion, and position. The assumption of normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

To evaluate the association between educational strategy and primary outcomes (maternal self-efficacy and satisfaction), parametric or non-parametric tests were applied, according to the distribution of the data. The Student’s t-test was used for normally distributed variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test was applied for variables without a normal distribution. Contingency tables were constructed for secondary outcomes such as exclusive breastfeeding rates. The independence of variables was assessed using Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, depending on the number of cases per cell. The relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated as measures of association, where appropriate. Statistical analyses were performed using RStudio (version 2024.03.1 + 402) and R (version 4.4.0.

An intention-to-treat analysis was conducted to ensure that all participants randomized into the study group were included in the primary analysis regardless of their adherence to the intervention. For participants lost to follow-up, descriptive analyses were performed to assess the potential differential losses between the groups.

Results

A total of 76 participants were assessed for eligibility, of whom 18 were excluded: one due to non-compliance with the inclusion criteria and 17 who declined to participate. The remaining 58 participants were randomized into two groups: 29 in the intervention group (mixed reality and traditional counseling) and 29 in the control group (traditional counseling only) (Fig. 2).

The baseline characteristics were balanced between the groups, with no statistically significant differences observed (Table 1). The largest proportion of participants (48.3%) had a community college or university education and 55.2% were housewives or students. A total of 94.8% had contributory health insurance and the majority did not consume alcohol or tobacco (93.1%). Notably, 98.3% of the participants expressed a desire to breastfeed and 58.6% had no previous living children. Half of the participants (50%) reported a previous breastfeeding experience, and exclusive breastfeeding during the first week was also observed in 50% of the participants, with both variables distributed similarly between groups (mixed reality: 48.3% vs. traditional counseling: 51.7%).

In terms of primary outcomes, the mean score on the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form (BSES-SF) was 63.31 (SD = 5.22) in the mixed reality group and 63.10 (SD = 4.57) in the traditional counseling group. The mean difference was 0.21 (95% CI: -2.37, 2.79; p = 0.87). Similarly, the mean score on the Maternal Breastfeeding Evaluation Scale (MBFES) was 133.48 (SD = 11.79) in the mixed reality group and 134.03 (SD = 9.50) in the control group, with a mean difference of -0.55 (95% CI: -6.18, 5.08; p = 0.84).

The secondary outcomes showed no significant differences between the groups. Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates during the first week of life were similar between the mixed reality and traditional counseling groups (50% vs. 50%, p = 1.00) (Table 2).

Exclusive breastfeeding during the first week of life was 93.1% in both the groups. When analyzing the association between exclusive breastfeeding and scores on the evaluation scales, no statistically significant differences were found. In the BSES-SF, the mean score was 63.3 for mothers practicing exclusive breastfeeding and 61.5 for those who did not practice exclusive breastfeeding (p = 0.47). In the MBFES, the mean scores were 134.3 and 126 for mothers with and without exclusive breastfeeding, respectively (p = 0.13) (Table 3).

Discussion

This controlled clinical trial evaluated the effect of an educational strategy based on mixed reality compared to traditional breastfeeding counseling on maternal self-efficacy and satisfaction using the validated BSES-SF and MBFES instruments. Although no statistically significant differences were observed between the two interventions, our findings provide valuable insights into breastfeeding practices in this population. Remarkably, the exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rate reached 93.1% in this study, significantly surpassing global and national averages of 37% and 36.1%, respectively7.

Self-efficacy and satisfaction are the key determinants of breastfeeding success. Maternal self-efficacy, defined as confidence in one’s ability to breastfeed effectively, is strongly associated with exposure to breastfeeding practices and presence of supportive networks12,19. A robust maternity care framework was established in the municipality of Sopó, including close follow-up by a multidisciplinary team, and structured maternity and paternity preparation courses aligned with Resolution 3280 of 2018. Additional initiatives, such as adherence to the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative and opening of a breastfeeding room in 2023, will further strengthen breastfeeding practices20. These combined efforts likely contribute to the high EBF rates observed in this study, underscoring the critical role of institutional- and community-level support.

In contrast, the literature highlights the detrimental effects of insufficient support and promotion of breastfeeding in regions with low breastfeeding rates, such as Ireland, which has reported the lowest initiation rate of human breastfeeding in Europe. An Irish study analyzing national prenatal education classes emphasized the importance of incorporating more realistic and interactive prenatal education21. This includes practical content, development of realistic expectations, and addressing mothers’ negative emotions regarding breastfeeding21. These key elements are closely aligned with the principles applied in this study.

Moreover, although our study did not directly assess the role of postnatal medical support, it is well established that guidance and encouragement from healthcare professionals can significantly influence breastfeeding outcomes. Evidence from randomized controlled trials demonstrates that organized support interventions provided by healthcare professionals or trained lay counselors can improve both breastfeeding duration and exclusivity14. A Cochrane review found that such support, delivered postnatally through structured visits or contacts, reduces the risk of early breastfeeding cessation by approximately 10% at six months and even more at earlier time points. These interventions, which include reassurance, practical advice, and education, appear effective regardless of whether the provider is a professional or trained peer supporter, regardless of the delivery mode (face-to-face, telephone, or digital). Similarly, a meta-analysis also supports the positive association between structured breastfeeding education and support, and higher rates of initiation and continuation of exclusive breastfeeding22. Future studies should evaluate the quality, intensity, and delivery mode of postnatal support as potential determinants of breastfeeding success.

Interestingly, the intention to breastfeed was nearly universal in this study population (98.3%) and is widely recognized as a predictor of successful breastfeeding23. Other protective factors identified included high educational level (88% of participants completed high school and 48.3% had higher education) and a low prevalence of smoking (Table 1). These characteristics may have provided a strong baseline for self-efficacy and satisfaction, potentially reducing the impact of mixed-reality interventions on these outcomes.

Motivational factors such as intrinsic motivation play a critical role in breastfeeding. According to the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), intrinsic motivation, driven by internal satisfaction, directly influences behaviors such as breastfeeding16,23. This theory has been successfully applied in health-related contexts, including nutrition, mental health, and pregnancy, demonstrating its consistency and effectiveness23,24. For instance, Tseng et al. implemented a three-week intervention based on SDT principles, with follow-ups extending to six months postpartum. Their findings revealed significantly higher self-efficacy and EBF rates in the intervention group than those in the control group18.

Regarding the satisfaction of pregnant mothers, participants in the mixed-reality group reported positive emotions toward the intervention, describing it as useful and educational. These findings align with those of studies incorporating virtual elements in education, which consistently reported high satisfaction among the participants12. This suggests that mixed reality could be a valuable tool for enhancing breastfeeding education even in resource-limited settings.

While our study did not find significant differences in EBF rates between the groups at one week postpartum, women who practiced EBF scored higher on the BSES-SF and MBFES than those who did not; however, these differences were not statistically significant. This observation aligns with evidence indicating that the critical period for breastfeeding cessation typically occurs between six weeks and three months postpartum and is influenced by factors such as formula marketing and misconceptions about newborn behavior13.

The formula industry plays a substantial role in shaping parental perceptions through extensive advertising, which often perpetuates misconceptions regarding the benefits of formula compared with human milk and restricts access to objective information. Moreover, the industry pathologizes normal physiological behaviors in newborns, such as crying, straining, and variations in sleep duration, and presents a formula for solving these behaviors6,13. Over the last four decades, this dynamic has contributed to the exponential growth of formula sales, contrary to global indicators of adherence to human breastfeeding13.

Beyond these societal and commercial influences, physical challenges such as nipple pain, mastitis, perceived insufficient milk supply, and early return to work have also been consistently identified as significant barriers to maintaining exclusive breastfeeding, particularly beyond the first few weeks postpartum25,26,27. These findings underscore the need for comprehensive support that addresses not only social and psychological factors but also the physical and occupational challenges faced by breastfeeding mothers.

Notably, during the 2022 COVID-19 pandemic, disruptions in formula supply chains have highlighted the vulnerability of formula-dependent feeding practices. This shortage prompted a historic increase in breastfeeding initiation rates in the U.S., particularly among populations with greater reliance on formula and limited access to supplies, demonstrating the resilience of breastfeeding practices in the absence of substitutes28.

This study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial to compare a mixed-reality educational intervention with traditional counseling in the context of breastfeeding. This approach focuses on early training to address the emotional and intimate aspects of breastfeeding beyond theoretical knowledge. Additionally, the use of validated instruments and the cost-effective nature of the materials make this strategy feasible for widespread application, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries.

However, the short follow-up period (one week postpartum) limits the ability to capture long-term challenges and barriers to EBF. The literature suggests that critical breastfeeding challenges often emerge between six weeks and three months postpartum, making extended follow-up essential for future studies. Furthermore, a more intensive intervention with multiple educational sessions could potentially yield greater improvement in self-efficacy and satisfaction.

Conclusions

This study found no statistically significant differences between the mixed reality-based educational strategy and traditional breastfeeding counseling in terms of maternal self-efficacy and satisfaction. However, high levels of self-efficacy and satisfaction were observed across the study population, along with exclusive breastfeeding rates during the first week of life that far exceeded both the national and global averages. These findings highlight the potential influence of a robust local framework that supports breastfeeding practices, including structured prenatal- and community-level interventions.

Future research should focus on randomized controlled trials that incorporate more intensive educational strategies involving multiple sessions and extended follow-up periods to better understand the long-term impact of these interventions on maternal self-efficacy, satisfaction, and exclusive breastfeeding rates. Additionally, further studies should explore the applicability of mixed-reality tools in diverse populations, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where access to innovative educational strategies may be limited but highly beneficial.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Becerra-Bulla, F., Rocha-Calderón, L. & Fonseca-Silva, D. M. Bermúdez-Gordillo, L. A. El Entorno familiar y social de La madre Como factor Que promueve o dificulta La Lactancia materna. Rev. Fac. Med. 63, 217–227 (2015).

World Health Organization & United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Estrategia Mundial Para La Alimentación Del Lactante y Del Niño Pequeño https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42695 (2003).

Rogger, E. et al. Guía Técnica Para La Consejería En Lactancia. www.gob.pe/minsa/ (2019).

World Health Organization & United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices: Definitions and Measurement Methods. (2021).

IHAN. Objetivos de desarrollo sostenible y lactancia materna. https://www.ihan.es/objetivos-de-desarrollo-sostenible-y-lactancia-materna/ (2025).

Pérez-Escamilla, R. et al. Breastfeeding: crucially important, but increasingly challenged in a market-driven world. Lancet 401, 472–485 (2023).

UNICEF, Breastfeeding - & UNICEF DATA. https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/breastfeeding/ (2025).

ICBF (Instuto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar). Encuesta Nacional de La Situación Nutricional ENSIN 2015. Colombia. (2018).

Alarcón Belmonte, I. et al. La Alfabetización digital Como elemento Clave En La Transformación digital de Las organizaciones En Salud. Aten Primaria. 56, 102880 (2024).

Pinzón Villate, G. Y. & Posada, A. Olaya vega, G. A. La consejería En Lactancia materna exclusiva: de La Teoría a La práctica. Revista De La. Facultad De Med. 64, 285–293 (2016).

Fundación, S. Plan Decenal de Lactancia Materna y Alimentación Complementaria - PDLMAC 2021–2030. https://scpwpoffloadmedia.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/25124424/PDLMAC_2021_2030-version-final-1.pdf (2021).

Tang, K., Gerling, K., Chen, W. & Geurts, L. Information and communication systems to tackle barriers to breastfeeding: systematic search and review. J. Med. Internet Res. 21, e13947 (2019).

Rollins, N. et al. Marketing of commercial milk formula: a system to capture parents, communities, science, and policy. Lancet 401, 486–502 (2023).

Gavine, A. et al. Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2022).

De Jager, E., Broadbent, J., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. & Skouteris, H. The role of psychosocial factors in exclusive breastfeeding to six months postpartum. Midwifery 30, 657–666 (2014).

García, D. et al. Configuración Teórica de La motivación de Salud desde La Teoría de La autodeterminación. Health Addictions. 15, 137 (2015).

Binns, C., Lee, M. & Low, W. Y. The Long-Term public health benefits of breastfeeding. Asia Pac. J. Public. Health. 28, 7–14 (2016).

Tseng, J. F. et al. Effectiveness of an integrated breastfeeding education program to improve self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding rate: A single-blind, randomised controlled study. Int J. Nurs. Stud. 111, (2020).

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215 (1977).

Kehinde, J., O’Donnell, C. & Grealish, A. A qualitative study on the perspectives of prenatal breastfeeding educational classes in ireland: implications for maternal breastfeeding decisions. PLoS One 19, (2024).

Kestler-Peleg, M., Shamir-Dardikman, M., Hermoni, D. & Ginzburg, K. Breastfeeding motivation and Self-Determination theory. Soc. Sci. Med. 144, 19–27 (2015).

Balogun, O. O. et al. Interventions for promoting the initiation of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database System. Rev. (2016).

Martín-Ramos, S. et al. [Breastfeeding in Spain and the factors related to its establishment and maintenance: LAyDI study (PAPenRed)]. Aten Primaria 56, (2024).

Gobierno Nacional de Colombia. Plan Nacional de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional (PNSAN) 2012–2019. https://www.icbf.gov.co/sites/default/files/pnsan.pdf (2013).

Gianni, M. L. et al. Breastfeeding difficulties and risk for early breastfeeding cessation. Nutrients 11, 2266 (2019).

Mangrio, E., Persson, K. & Bramhagen, A. Sociodemographic, physical, mental and social factors in the cessation of breastfeeding before 6 months: a systematic review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 32, 451–465 (2018).

Brown, C. R. L., Dodds, L., Legge, A., Bryanton, J. & Semenic, S. Factors influencing the reasons why mothers stop breastfeeding. Can. J. Public Health 105, e179–e185 (2014).

Seoane Estruel, L. & Andreyeva, T. Breastfeeding trends following the US infant formula shortage. Pediatrics 155, (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Universidad de La Sabana, Cundinamarca, Colombia, and Hospital Divino Salvador de Sopó, Colombia, for their invaluable support during the completion of this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Universidad de La Sabana (grant number MEDESP-27-2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMM, LCR, FRM and SAP conceived of and designed the study. MP, AMM, LCR and FRM performed selection, recruitment, enrollment of participants, and data collection. SAP analyzed the data. SAP, AMM, LCR, and FRM contributed to data interpretation. AMM, LCR, FRM, MP and SAP drafted the manuscript. AMM, LCR, FRM, MP, and SAP reviewed and approved the final version of this manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declaration

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de La Sabana (No. 130 on May 27, 2024) in compliance with Resolution 8430 of 1993, which classifies the research as a minimal risk. All participants provided written informed consent before their inclusion in the study. No financial incentives or compensation was offered to the participants to ensure their autonomy in deciding to join the study. Clinical trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT06800521 (29/01/2025).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Montoya-Moncada, A., Cuero-Ríos, L., Rodríguez-Morales, F. et al. Exploring the role of mixed reality education in maternal self efficacy and satisfaction with breastfeeding. Sci Rep 15, 28484 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14319-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14319-y