Abstract

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a very heterogeneous disease with significant impact on health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL). Our objective was to assess and identify predictors of HRQoL in a 3-year follow-up period among PsA patients. Patients with PsA included in the Rheumatic Diseases Portuguese Register (Reuma.pt), with HRQoL data measured by the EuroQoL five Dimensions (EQ-5D) with at least two evaluations throughout a 3-year period, were analysed. Statistics included t-tests, logit and linear mixed models and univariable and multivariable linear regression. PsA patients’ (n = 342) mean age 51.0 (12.2) years, 48.5% being female, mean disease duration 11.8 (9.3) years with a follow-up period of 3-years had a mean EQ-5D of 0.53 (0.28), 0.59 (0.29), and 0.58 (0.28) at baseline, 1-year and 3-year evaluations, respectively. During the follow-up period, EQ-5D score and EQ VAS, significantly improved at both time-point assessments, compared to baseline. Poorer HRQoL was significantly associated with older age (β=-0.004; p-value = 0.008), female sex (β=-0.092; p-value = 0.01), non-employment (β=-0.112; p-value = 0.018), higher disease activity (β=-0.005; p-value < 0.001), prior exposure of three or more biologics at baseline and switching of biologic therapy during the study follow-up [(β=-0.182; p-value = 0.04); (β=-0.150; p-value = 0.002), respectively]. Our study provides important insights into the long-term predictors of HRQoL in PsA patients, highlighting the influence of sociodemographic factors, disease activity and therapeutic approach (prior use and switch/cycle of biologic therapies) on HRQoL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA), is a chronic inflammatory condition with musculoskeletal manifestations including peripheral arthritis, axial disease, dactylitis, and enthesitis often accompanied by skin and/or nail psoriasis.

The prevalence of psoriasis is estimated to be between 2% and 3%, and the prevalence of inflammatory arthritis among patients with psoriasis has shown a wide range, from 6–42%1. In Portugal, the estimated prevalence of PsA is 0.3%2.

The disease progression of PsA exhibits significant variability. Some patients experiencing mild symptoms while others may develop severe and debilitating disease1. Both the musculoskeletal and the skin manifestations can profoundly affect health-related quality of life (HRQoL)3, resulting in substantial impairment across its physical, emotional, and social domains4.

In recent years, the assessment of HRQoL in rheumatic diseases has gained increasing significance. HRQoL assessments offer valuable insights because they capture the patient´s subjective experience of how the disease affects their daily functioning, emotional well-being, and social interactions. These aspects may not necessarily be reflected in the objective physical and symptomatic evaluations. Several studies have focused into the factors linked to HRQoL, encompassing sociodemographic, clinical and psychological factors5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Nevertheless, several of these studies have been cross-sectional6,7,8,9,10,14,15 or had limited follow-up periods5,12,16, making our understanding of long-term predictors of HRQoL in PsA not well understood.

Patients with more severe or active disease, such as those with higher levels of pain, joint swelling and stiffness, often experience lower HRQoL9,16,17. In recent years the introduction of new therapies such as biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDS) and target synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs), have demonstrated significant reductions in disease activity and subsequent impact on HRQoL18. However, various other factors have been identified, namely comorbidities, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity19, psychological factors, such as depression and anxiety20 and, older age11,17 and female sex7,8.

In this study, our goal is to identify the long-term predictors of HRQoL and their interaction in a real-world Portuguese cohort of patients with PsA providing a better understanding of the long-term course of HRQoL in these patients.

Materials and methods

Data Source and Study Population

In this prospective multicenter cohort study, we included adult PsA patients (≥ 18 years), according to the rheumatologist perspective, independently of the phenotype or the therapeutic regimen, registered in the Rheumatic Diseases Portuguese Register (Reuma.pt), from June 2008 to June 2022. As inclusion criteria patients were required to have: (1) A HRQoL evaluation at baseline with the EuroQol five Dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D) and (2) At least one more HRQoL evaluation with the EQ-5D (at 1-year and/or 3-years, as available). We excluded patients with less than 1 year of follow-up or those who had fewer than two HRQoL evaluations during the 3-year follow-up period.

Reuma.pt, a nationwide register (www.reuma.pt), supported by the Portuguese Society of Rheumatology, became active in 2008 and includes patients with various rheumatic diseases, including PsA. This study was approved by the national ethical commission of Portuguese Institute of Rheumatology (reference number 2/2022) and all participants signed the informed consent.

Data collection

Outcome

HRQoL was evaluated using the EQ-5D, 3 levels, validated for the Portuguese population21. The EQ-5D comprises a health descriptive component and a general health visual analogic scale (VAS) evaluation. The descriptive component evaluates five dimensions, each describing a different aspect of health: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each dimension has three levels: no problems, some problems, and extreme problems (labeled 1–3, respectively). The descriptive system was converted into a summary index score with 0 equivalent to death and 1 to full health. The Euro Qol VAS (EQ VAS) is a 20-centimeter vertical scale of 0–100 points, where, similarly, scores of 0 and 100 correspond to the “worst imaginable health state” and the “best imaginable health state,” respectively.

Covariates of interest

Sociodemographic data (age, sex, years of education, marital status), employment status and profession (patients were classified in blue-collar and white-collar workers according to criteria previously used)22, lifestyle habits (smoking and alcohol intake), anthropometric data (weight, height, body mass index [BMI), disease characteristics (age of first symptoms, age of diagnosis, diagnostic delay, disease duration, disease phenotype), and extra-articular manifestations (enthesitis, dactylitis, psoriasis) were collected at baseline. Concomitant treatments [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs) (methotrexate, sulfasalazine, leflunomide), bDMARDs [tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors (TNFi) (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, infliximab, golimumab), secukinumab, ustekinumab, tsDMARDs (tofacitinib)] were collected at baseline and during follow-up.

In each visit were collected data on disease activity [tender joint count (TJC68); swollen joint count (SJC66); patient’s global assessment of the disease in the last week (PtGA), registered on a visual analog scale (VAS), 0–100 mm; physician’s global assessment of the disease (PhGA), (VAS, 0–100 mm); erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); C-reactive protein (CRP, mg/l); Disease Activity Index for Psoriatic Arthritis with CRP (DAPSA)23 and Disease activity score 28 joint count, four variables-CRP (DAS28 4vCRP) for peripheral disease; Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score with CRP (ASDAS) for axial disease24; Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score (MASES)25, psoriasis (VAS, 0–100 mm); number of fingers with dactylitis]. Data was extracted from the Reuma.pt database on the 06 of June 2022.

Definitions

States of disease activity for DAPSA were defined as: remission ≤ 4; low disease activity 5–14; moderate disease activity 15–28; high disease activity > 2823. States of disease activity for ASDAS were defined as: inactive disease < 1.3; low disease activity 1.3–2.1; high disease activity 2.1–3.5; very high disease activity > 3.524.

Switching was defined as the change of a b/tsDMARDs to another b/tsDMARDs with a different mode of action, and cycling was defined as the change to a b/tsDMARDs with the same mode of action. It was registered at baseline and during the study follow-up.

For the purpose of statistical analysis, the disease phenotypes, according to the patients’ rheumatologist, were grouped into two categories: predominant axial disease and predominant peripheral disease which included symmetric polyarthritis, oligoarthritis, predominant distal interphalangeal involvement, and mutilans arthritis.

To gain a deeper understanding of the impact of b/tsDMARDs therapy on long-term HRQoL we conducted a sub-group analysis in patients who initiated b/tsDMARDs at baseline or during the study follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Baseline participant characteristics are shown as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables and mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables.

To compare the EQ-5D domains at the two or three considered time-points, logit mixed models were used; T-tests for repeated measures were used for the EQ-5D score and the EQ VAS score. The potential associated factors to HRQoL over time were assessed considering linear mixed models, considering varying intercepts for each participant and independent covariance structure. Univariate models were computed first to test the significance of potential predictors, with p\(\:\le\:\:\)0.20 as the selection criterion. Then, with a backward conditional method, we sequentially remove the variables not statistically significant and compared through likelihood ratio tests until the final model was reached. Determinants of HRQoL in the groups considered according to b/tsDMARD exposure, were assessed with the same methodology.

All analyses were performed with STATA v16.1 considering a level of significance of 0.05.

Results

Out of the 531 patients, and according to the inclusion criteria, 342 were eligible for the study analyses, having at least two EQ-5D evaluations within a three-year period. Of the 342 patients, 136 patients had EQ-5D evaluations at baseline, after 1-year and 3-years of follow-up. Two hundred and five patients had EQ-5D evaluations in two time-points of the follow-up period, 173 patients at baseline and after 1-year, and 32 patients at baseline and after 3-years.

Sociodemographic, lifestyle, and anthropometric data characteristics

The patients’ mean age was 51.0 (12.2) years, with 48.5% being female.

At baseline, patients reported on average 9.0 years (4.4) of education, and 153 (59.8%) were employed, mostly in blue-collar type of work (59.7%). Most of the patients (n = 174, 78.7%) were married. Regarding lifestyle habits, ever smoking (past or present) was referred by 32.6% of patients, and ever alcohol intake (past or present) was referred by 24.4% of patients. A significant number of patients were over weighted (n = 104, 41.8%) or obese (n = 53, 21.1%). Sociodemographic, lifestyle, and anthropometric data characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Clinical characteristics

Mean disease duration was 11.8 (9.3) years, with a diagnostic delay of 3.1 (4.9) years at baseline.

Symmetrical polyarthritis was the predominant phenotype in 140 patients (52.0%), followed by asymmetric oligoarthritis in 61 (22.7%) patients, predominant axial involvement in 55 (20.5%) patients, distal interphalangeal arthritis in 14 (3.7%), and mutilans arthritis in 3 (1.1%) patients. Sixty-nine patients (20.2%) had no information on disease phenotype (Table 1).

At baseline, patients had a mean PtGA of 41.6 (28.8), global pain VAS 41.0 (29.2), CPR 9.5 (18.5) mg/l, mean tender joints 5.6 (9.0) and mean swollen joints 1.9 (3.3). As expected PhGA (24.1 (21.9)) was lower than PtGA (41.6 (28.8)), with a mean value of DAS28 and DAPSA of 3.2 (1.6) and 24.7 (26.1), respectively; 161 patients (55.4%) had moderate or high disease activity, according to DAPSA criteria. For axial disease, disease activity was evaluated with ASDAS, showing a mean value of 2.8 (1.2); 82 (67.5%) patients had high or very high disease activity, according to ASDAS criteria. We also analyzed the disease activity by sex. Regarding DAPSA at baseline, the mean value for women was 30.08 (2.35), while for men it was 19.56 (1.86). This difference was statistically significant (t = 3.52, p = 0.0003). Similar findings were observed for ASDAS, which was higher in women (t = 3.07, p = 0.001). Additionally, women reported significantly higher scores for pain VAS (t = 5.29, p < 0.001) and global assessment VAS (t = 6.13, p < 0.001).

Most patients (n = 236, 69.0%) were on b/tsDMARDS. Disease characteristics and therapies at baseline and follow-up are summarized in Table 2.

Quality of Life

HRQoL was seriously compromised in PsA patients, with a mean EQ-5D score of 0.53 (0.28) at baseline and 0.59 (0.29) and 0.58 (0.28) at 1-year and 3-year evaluations, respectively. These values reflect a worse HRQoL, during the follow-up period, in comparison to the Portuguese population [normative value of 0.758]26. Furthermore, global health expressed by the value of EQ VAS was 62.5 (22.6) at baseline and 68.7 (20.9) and 67.7 (21.5) at first and second time-point evaluations, respectively, also reflecting a lower global health in comparison to general Portuguese population [normative value of 74.9]26. Patients reported problems in all EQ-5D dimensions at baseline, with 271 (79.3%) patients reporting moderate to extreme pain or discomfort, followed by problems with usual activities (n = 193; 56.4%), problems with mobility (n = 177; 51.8%), anxiety or depression (n = 168; 49.1%), and problems with self-care (n = 115; 33.6%). During follow-up period, EQ-5D score and EQ VAS, significantly improved at both time-point evaluations, compared to baseline. Additionally, at the one-year evaluation, all domains of HRQoL were significantly better compared to baseline, but at the three-year evaluation, improvements in self-care and anxiety/depression domains were not significantly better than on the baseline. There were no significant improvements between 1-year and 3-year evaluations. Results on HRQoL evaluated by EQ-5D in the three time-points are summarized in Table 3.

In our sub-group analysis in patients who initiated b/tsDMARDs at baseline or during the study follow-up, at 1-year we observed a significant improvement in mobility, self-care and usual activities but not in pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. However, after 3 years of follow-up, these dimensions were significantly improved compared to baseline. During the follow-up period, EQ-5D score and EQ VAS, significantly improved at 1-year and 3-year evaluations, compared to baseline. Results on HRQoL evaluated by EQ-5D in the three time-points, for this subgroup, are summarized in Table 4.

Determinants of HRQoL

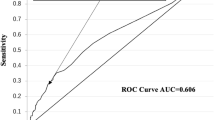

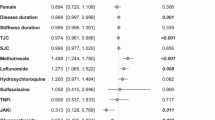

After univariate regression analysis we performed a multivariate model to assess determinants of HRQoL (Table 5).

Worse HRQoL was associated with an older age (β=−0.004; p-value = 0.008), female sex (β=−0.092; p-value = 0.01), and higher disease activity evaluated by DAPSA (β=−0.005; p-value < 0.001). Patients who were exposed to three or more b/tsDMARDS at baseline had poorer HRQoL than patients who never experienced b/tsDMARDS (β=−0.182; p-value = 0.04); to switched b/tsDMARDs therapy was also associated with poorer HRQoL compared to maintaining the same therapy during the follow-up period (β=−0.150; p-value = 0.002), but to cycled b/tsDMARDs therapy was not associated with poorer HRQoL compared to patients that maintained the same b/tsDMARDs during the follow-up period (β=−0.100; p-value = 0.862).

To uncover the specific effects of b/tsDMARDs therapy on HRQoL we performed a sub-group analysis exploring determinants of HRQoL in patients who initiated b/tsDMARDs therapy either at baseline or during the study follow-up. Disease activity consistently emerged as a significant factor influencing HRQoL. Also, not being employed, an older age at diagnosis, and cycling or switching of b/tsDMARDs where associated with poorer HRQoL (Table 6).

Discussion

In this study, we conducted an analysis of the determinants of HRQoL in a real-world population of patients with PsA, covering the full spectrum of the disease.

Our findings indicate that patients with PsA experience a significant decrease in HRQoL, compared to the general population in Portugal. This was evident trough lower scores on the EQ-5D assessment and poorer ratings of global health on the EQ VAS. Several factors influenced HRQoL in our cohort, including age, sex, disease activity, previous use of biologic therapies, and in particular the switching or cycling of biologic therapy during the follow-up period. Moreover, our study revealed that a majority of patients experienced moderate to extreme pain, which had a negative impact on their daily activities and mobility. Despite the availability of numerous treatment options, PsA patients still faced a considerable burden of disease. It is worth noting that a significant proportion (70%) of patients reported moderate pain, and a small percentage (9%) experienced extreme pain, suggesting that pain management was inadequate and not solely related to disease activity. However, over the course of the study follow-up period, improvements were observed in all domains, and a larger proportion of patients reported an absence of problems in various domains since the first year. At the one-year evaluation, HRQoL had significantly improved compared to baseline, but no further improvements were observed between the one-year and three-year evaluations. We believe HRQoL is closely linked to disease activity. One-third of our patients were about to initiate b/tsDMARDs, which corresponded with an improvement in both disease activity and HRQoL at T1, with no significant changes in either outcome measure thereafter. These findings are in line with the results of a recent study by Wilk et al.13, where during a 5-year follow-up, no significant decline in HRQoL, assessed by a 15-dimension instrument, was observed. The authors attribute their findings to the widespread adoption of new treatments, leading to improved disease control and preservation of baseline HRQoL.

Overall, our results are consistent with previous studies6,9,16, reflecting a general decrease of HRQoL among patients with PsA. In a study conducted by Mlcoch et al.16 with 228 PsA patients, they reported an EQ-5D score of 0.68, indicating a better HRQoL compared to our cohort. Similarly, Mease et al. (7) examined a larger cohort of 1530 patients and found an EQ-5D score of 0.8 and an EQ VAS of 72.3. The differences in HRQoL scores between these studies and our cohort, may be attributed to variations in disease activity levels. Our cohort had high disease activity, based on DAPSA criteria, whereas the previous cohorts had low or moderate disease activity. However, it is worth noting that Moraes et al.9 evaluated 212 Brazilian patients with high disease activity according to CDAI cut-offs, and still observed better EQ-5D score compared to our patients. This discrepancy could be attributed not only to the disease activity itself but with the use of different disease activity scoring systems or potential differences in the study cohorts or cultural aspects. Moreover, it is important to highlight that approximately one-third of our cohort consisted of patients who were about to initiate b/tsDMARD.

The association between older age and poorer HRQoL remains a topic of debate in the existent literature7,11,15,17, but our findings are consistent with previous research7,15. One possible explanation for this association is the natural progression of the disease, where aging can lead to increase disability27 and the accumulation of comorbidities28. These factors significantly contribute to the burden of the disease and subsequently reduce HRQoL19.

However, it’s important to note that some studies did not find a significant association between older age and HRQoL11,17. This discrepancy may arise from the understanding that although aging can lead to cognitive and physical declines, well-being may not necessarily decrease in older individuals compared to younger individuals, as suggested in some studies29.

The observation that women with PsA have significantly lower HRQoL compared to men has been reported by other authors8,30,31. For instance, a recent study by Gossec et al.8, involving 2270 PsA patients found that, despite similar levels of disease activity, women reported lower HRQoL, greater disability, and higher levels of work impairment compared to men. Similarly, in a cohort of 405 PsA patients, Wervers et al.7, found that women had worse HRQoL than men, as indicated by the physical and mental global scores of the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36). We observed that disease activity was higher in women than in men. Mulder et al.32, also reported higher disease activity in women compared to men, as assessed by the Psoriatic Arthritis Disease Activity Score (PASDAS), which impacts HRQoL. We will explore this topic further.

The underlying reasons for these differences in HRQoL between sexes are not yet fully understood. Several factors have been proposed, including biologic factors, which includes genetic mechanisms, and sex hormones, and also environmental and social factors31,33.

Our findings revealed a significant negative correlation between disease activity and HRQoL in patients with PsA, indicating that higher disease activity was associated with worse HRQoL. These results were consistent across the all group and the subgroup of patients about to initiate b/tsDMARD therapy. This aligns with previous research that has also demonstrated a negative impact of disease activity on HRQoL in PsA patients9,17. Furthermore, a 2-year longitudinal study by Mlcoch et al.16, identified DAPSA and clinical DAPSA as the most significant and stable predictors of HRQoL assessed by EQ-5D.

Additionally, other studies have shown that patients who achieve minimal disease activity (MDA) tend to have higher HRQoL compared to those without MDA34. In addition, attaining MDA, regardless of the time elapsed since diagnosis, is also associated with subsequent improvements in HRQoL over time35.

However, contrasting results have been reported in some studies. For instance, the study by Haugeberg et al.15, did not find a significant association between disease activity and HRQoL when evaluated by the 15-Dimensional Questionnaire in multivariate analyses. Similarly, in the study by Skougaard et al.36 disease activity assessed by the DAS28-CRP was associated with worse physical and mental component summary (PCS and MCS, respectively) of SF-36 in univariate analyses, but not in the multivariate model. Instead, changes in HAQ, fatigue and pain VAS had a greater impact on PCS and MCS scores than changes in disease activity. One possible explanation for these discrepancies could be the choice of assessment instruments used in these studies. The 15-Dimensional Questionnaire, being a generic questionnaire, may not accurately capture the specific impact of PsA on HRQoL. Additionally, the use of a score based on a 28- joint count for evaluating disease activity may not adequately capture the frequent involvement of lower limbs in PsA patients.

In our study, we gained a deeper understanding of the impact of b/tsDMARDs therapies on HRQoL through subgroup analysis. Previous studies have primarily assessed the effectiveness and survival on treatment when employing cycling or switching strategies of b/tsDMARDs, with limited data available on their influence on HRQoL (31,32). In our sub-group analysis, switching as well as cycling were associated with poorer HRQoL in patients who initiated b/tsDMARD therapy.

Patients initiating b/tsDMARD therapy during the study follow-up and exposed to cycling or switching of b/tsDMARD therapy, likely have a more severe or refractory disease, impacting their HRQoL irrespective of treatment. Furthermore, the frustration and uncertainty associated with changing treatment regimens may contribute to a decline in HRQoL.

Fagerli et al.37, studied PsA patients in the NOR-DMARD study and found that those switching TNFi (first or second switch) had significantly poorer responses than non-switchers, reporting worse HRQoL, as evaluated by the SF-36. Although our study differed slightly, as we did not compare two groups, the findings align with Fagerli et al.‘s results (31). Ariani et al.38 compared cycling and swapping strategies in PsA patients after experiencing a first biologic failure, finding no significant differences in outcomes, but notably, they did not assess the impact on HRQoL. Moreover, Mease et al.39 found that patients from the Corrona registry who discontinued or switched treatment (either TNFi-naïve or TNFi-experienced) had worse HRQoL scores, as measured by the EQ-5D, compared to those who continued with the same TNFi therapy, thought this difference was not statistically significant.

Clinicians should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of multiple biologic therapies and consider alternative treatment options for patients who have not responded to or have experienced side effects from previous biologics. Further research is needed to confirm these findings and explore the underlying mechanisms contributing to observed differences in HRQoL among patients who switch or cycle biologic therapies.

Strengths and limitations

Our study possesses both strengths and limitations that merit consideration. A significant strength lies in its grounding in real-world practice, with the incorporation of multiple validated outcomes and disease activity assessments commonly employed in clinical studies and endorsed by prestigious organizations. Furthermore, the nationwide scope of our study, incorporating data from both private and public hospitals, enhances the generalizability of our findings to diverse patient populations and healthcare settings. The longitudinal design of the study allowed for the examination of changes over time, establishing causality with factors associated with HRQoL and providing valuable insights into PsA management.

However, registry studies, including ours, are susceptible to a primary limitation - missing data- which can compromise the precision and accuracy of the results. Despite our efforts to address this limitation, by requesting participant centers to complete the central database comprehensively, we were still unable to include all PsA patients in our analyses due to missing EQ-5D evaluations. Additionally, some patients had only two out of three EQ-5D evaluations, potentially impacting our results. We used linear mixed models, which efficiently handles missing data under the missing at random (MAR) assumption, allowing for the inclusion of all available data without imputation or case exclusion. Baseline comparisons showed no significant differences between patients with complete and incomplete data, supporting the MAR assumption. However, if the data were missing not at random (MNAR), potential bias could not be fully addressed. This poses a moderate limitation, and results should be interpreted with caution, particularly in terms of generalizability.

The exclusion of comorbidities, owing to high volume of missing information, represents another limitation. While we partly addressed this by adjusting for age, its influence on our results cannot be entirely discounted. Finally, our study shares the common limitations of observational research, including potential confounding and selection bias.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study provides valuable insights into the management of PsA patients and the factors influencing HRQoL in a real-world setting, thereby enhancing our understanding of this complex disease. We discovered that PsA patients experience significantly poorer HRQoL compared to the general population. Furthermore, we observed a significant improvement in HRQoL over time, although these improvements were not sustained in all domains. Predictors of poorer HRQoL included age, female sex, not being employed and high disease activity. Additionally, patients exposed to biologic therapies requiring switching or cycling were found to be at higher risk of poor HRQoL.

Our findings underscore the necessity for targeted interventions designed to enhance HRQoL in PsA patients, particularly in those with identified risk factors. By addressing these factors, healthcare professionals can enhance the overall well-being of PsA patients, leading to improved disease outcomes and enhanced HRQoL.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Sociedade Portuguesa de Reumatologia but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Sociedade Portuguesa de Reumatologia.

References

Gladman, D. D., Antoni, C., Mease, P., Clegg, D. O. & Nash, O. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64, 14–17 (2005).

Rodrigues, J. et al. Psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis impact on health-related quality of life and working life: a comparative population-based study. Acta Reumatol. Port. (2019). 44:254–65. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32008031

Husted, J. A., Gladman, D. D., Farewell, V. T. & Cook, R. J. Health-related quality of life of patients with psoriatic arthritis: A comparison with patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 45, 151–158 (2001).

Salaffi, F., Carotti, M., Gasparini, S., Intorcia, M. & Grassi, W. The health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis: A comparison with a selected sample of healthy people. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 7, 1–12 (2009).

Kavanaugh, A. et al. The contribution of joint and skin improvements to the health-related quality of life of patients with psoriatic arthritis: A post hoc analysis of two randomised controlled studies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 78, 1215–1219 (2019).

Mease, P. J. et al. Influence of axial involvement on clinical characteristics of psoriatic arthritis: analysis from the Corrona psoriatic arthritis/spondyloarthritis registry. J. Rheumatol. 45, 1389–1396 (2018).

Wervers, K. et al. Influence of disease manifestations on health-related quality of life in early psoriatic arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 45, 1526–1531 (2018).

Gossec, L. et al. Women with psoriatic arthritis experience higher disease burden than men: findings from a Real-World survey in the united States and Europe. J. Rheumatol. 50, 192–196 (2023).

Moraes, F. A. et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Psoriatic Arthritis: Findings and Implications. Value Heal. Reg. Issues 26:135–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vhri.2021.06.003 (2021).

Gratacós, J. et al. Health-related quality of life in psoriatic arthritis patients in Spain. Reumatol Clin. 10, 25–31 (2014).

Freites Nuñez, D. et al. Factors associated with Health-Related quality of life in psoriatic arthritis patients: A longitudinal analysis. Rheumatol. Ther. 8, 1341–1354 (2021).

Michelsen, B. et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis: data from the prospective multicentre NOR-DMARD study compared with Norwegian general population controls. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 77, 1290–1294 (2018).

Wilk, M. et al. Exploring 5-year changes in general and skin health-related quality of life in psoriatic arthritis patients. Rheumatol. Int. 44:675–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-024-05536-1 (2024).

Conaghan, P. G. et al. Relationship of pain and fatigue with health-related quality of life and work in patients with psoriatic arthritis on TNFi: results of a multi-national real-world study. RMD Open 6:e001240. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32611650 (2020).

Haugeberg, G., Michelsen, B. & Kavanaugh, A. Impact of skin, musculoskeletal and psychosocial aspects on quality of life in psoriatic arthritis patients: A cross-sectional study of outpatient clinic patients in the biologic treatment era. RMD open 6:1–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32409518 (2020).

Mlcoch, T. et al. Mapping quality of life (EQ-5D) from dapsa, clinical DAPsA and HAQ in psoriatic arthritis. Patient 11, 329–340 (2018).

Attar, S. et al. Burden and Disease Characteristics of Psoriatic Arthritis at a Tertiary Center. Cureus 14:e27359. https://www.cureus.com/articles/102221-burden-and-disease-characteristics-of-psoriatic-arthritis-among-king-abdulaziz-university-hospital-patients (2022).

Lu, Y., Dai, Z., Lu, Y. & Chang, F. Effects of bDMARDs on quality of life in patients with psoriatic arthritis: meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 12, e058497 (2022).

Husted, J. A., Thavaneswaran, A., Chandran, V. & Gladman, D. D. Incremental effects of comorbidity on quality of life in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 40, 1349–1356 (2013).

McDonough, E. et al. Depression and anxiety in psoriatic disease: prevalence and associated factors. J. Rheumatol. 41, 887–896 (2014).

Ferreira, L. N., Ferreira, P. L., Pereira, L. N. & Oppe, M. The valuation of the EQ-5D in portugal. Qual. Life Res. 23, 413–423 (2014).

Ramiro, S. et al. Lifestyle factors may modify the effect of disease activity on radiographic progression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a longitudinal analysis. RMD Open https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000153 (2015).

Schoels, M. M., Aletaha, D., Alasti, F. & Smolen, J. S. Disease activity in psoriatic arthritis (PsA): defining remission and treatment success using the DAPSA score. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75:811–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207507 (2016).

Machado, P. et al. Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease activity states and improvement scores. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70:47–53. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2010.138594 (2011).

Heuft-Dorenbosch, L. et al. Assessment of enthesitis in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 62:127–32. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.62.2.127 (2003)

Ferreira, L. N., Ferreira, P. L., Pereira, L. N. & Oppe, M. EQ-5D Portuguese population norms. Qual. Life Res. 23, 425–430 (2014).

Verbrugge, L. M. & Yang, L. Aging with Disability and Disability with Aging. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 12:253–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/104420730201200405 (2002).

Fragoulis, G. E., Nikiphorou, E., McInnes, I. B. & Siebert, S. Does age matter in psoriatic arthritis?? A narrative review. J. Rheumatol. 49, 1085–1091 (2022).

Wettstein, M., Eich, W., Bieber, C. & Tesarz, J. Pain intensity, disability, and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain: does age matter? Pain med. (United States). 20, 464–475 (2019).

Duruöz, M. T. et al. Gender-related differences in disease activity and clinical features in patients with peripheral psoriatic arthritis: A multi-center study. Jt. bone spine. 88:105177. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33771757 (2021).

Eder, L. & Chandran, V. Gender-related differences in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Int. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 7, 641–649 (2012).

Mulder, M. L. M. et al. Measuring disease activity in psoriatic arthritis: PASDAS implementation in a tightly monitored cohort reveals residual disease burden. Rheumatol. (United Kingdom). 60, 3165–3175 (2021).

Bragazzi, N. L., Bridgewood, C., Watad, A., Damiani, G. & McGonagle, D. Sex-Based medicine Meets psoriatic arthritis: lessons learned and to learn. Front. Immunol. 13, 1–7 (2022).

Chiowchanwisawakit, P., Srinonprasert, V., Thaweeratthakul, P. & Katchamart, W. Disease activity and functional status associated with health-related quality of life and patient-acceptable symptom state in patients with psoriatic arthritis in thailand: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 22, 700–707 (2019).

Wervers, K. et al. Time to minimal disease activity in relation to quality of life, productivity, and radiographic damage 1 year after diagnosis in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 21, 1–7 (2019).

Skougaard, M. et al. Change in psoriatic arthritis outcome measures impacts SF-36 physical and mental component scores differently: an observational cohort study. Rheumatol. Adv. Pract. 5, 1–10 (2021).

Fagerli, K. M. et al. Switching between TNF inhibitors in psoriatic arthritis: data from the NOR-DMARD study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72, 1840–1844 (2013).

Ariani, A. et al. Cycling or swap biologics and small molecules in psoriatic arthritis: observations from a real-life single center cohort. Med. (Baltim). 100, e25300 (2021).

Mease, P. J. et al. Discontinuation and switching patterns of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) in TNFi-naive and TNFi-experienced patients with psoriatic arthritis: an observational study from the US-based Corrona registry. RMD Open. 5:e000880. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000880 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank patients included in Reuma.pt for their contribution to this study, all Rheumatologists involved in data collection and the Portuguese Society of Rheumatology staff for data management.

Funding

This work was supported by a research grant from the Portuguese Society of Rheumatology.

HS has received a doctoral grant from Portuguese Society of Rheumatology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HS, ARH, FPS and AMR analyzed and interpreted the data. ARH performed the statistical analyses. HS was a major contributor in writing the manuscript, and all authors commented on previous version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Reuma.pt is approved by the Portuguese Data Protection Authority and all patients have signed a written informed consent before inclusion in the register. Study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Instituto Português de Reumatologia (reference number 2/2022).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Santos, H., Henriques, A.R., Canhão, H. et al. Sociodemographic factors and biologic therapy exposure impacting health-related quality of life in psoriatic arthritis - findings from a nationwide registry Reuma.pt. Sci Rep 15, 29711 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14790-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14790-7