Abstract

Counselors are professionals who provide guidance and psychological counseling services in places such as educational institutions and guidance and research centers. The main purpose of this cross-sectional quantitative study was to investigate the relationship between compassion fatigue (CF) and compassion satisfaction (CS) among Turkish counselors and the moderating role of self-compassion in this relationship. A sample of 367 counselors (mean age 36.56 years: 52% female) completed an online survey including measures. Pearson correlation and moderation analyses were conducted. CF and CS were significantly related to each other (r = − .77), while self-compassion and CF were highly negatively correlated (r = − .68). Furthermore, a significant positive relationship was found between self-compassion and CS (r = .70). The analysis revealed that self-compassion moderated the relationship between CF and CS. The present results suggest that self-compassion may act as a protective factor against the effects of CF. However, the cross-sectional design limits causal interpretations, and self-report measures may be subject to response biases. Future research should consider longitudinal designs and explore intervention strategies to enhance self-compassion among counselors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While compassion has historically been explored across diverse fields like philosophy, religion, and ethics, its scientific investigation, particularly within psychology and mental health, has gained significant momentum over the past two decades1,2. This heightened interest, largely influenced by the rise of positive psychology3, underscores compassion’s therapeutic function, healing capacity, and interpersonal benefits across various professional contexts, including healthcare, education, and social work4,5. Despite this growing recognition of compassion’s importance in supporting individuals, a notable gap exists concerning the specific compassion experiences of mental health professionals, especially counselors. Although self-compassion is acknowledged as a crucial concept in mental health and therapy research6,7,8, its comprehensive investigation among counselors remains limited9. Given that counselors inherently rely on compassion in their helping roles10,11, a deeper understanding of their compassion experiences, including self-compassion, is essential.

As professionals providing guidance and psychological counseling services, especially in school settings, counselors play a critical role in supporting students’ academic, social, and emotional development12,13. Their work involves addressing a wide range of challenging student problems, including academic difficulties, mental health issues like depression and anxiety, and severe social concerns such as bullying or addiction14,15. Constantly engaging with distress and crisis situations16,17 can expose counselors to significant emotional strain, potentially leading to compassion fatigue (CF), characterized by professional burnout and secondary traumatic stress18,19,20. Conversely, successfully guiding students through their difficulties and observing positive outcomes can lead to profound professional and emotional fulfillment, known as compassion satisfaction (CS)21,22.

CF and CS

CF and CS are concepts related to occupational quality of life. Occupational quality of life is an important quality that a person feels when helping people in their professional life. This quality shows up in negative (CF) and positive (CS) ways. The negative aspect is divided into two parts: burnout and secondary traumatic stress. The positive aspect is known as CS21.

The concept of CF, introduced by Figley in the 1980s, was originally used to refer to secondary trauma18. CF is a state of burnout experienced due to the support and help provided to individuals who are suffering, victimized, and in need23. Counselors who provide psychological support in schools may also experience CF, as they serve many students who suffer from emotional and social problems. Counselors who encounter cases such as trauma, suicide, abuse, and violence sometimes have to carry out psychosocial activities lasting weeks or months. Through these long-term efforts, counselors are likely to experience stress, feelings of inadequacy, and burnout in their professional lives24. Counselors may develop CF while helping students, parents, or other school staff, which can cause them to become indifferent and insensitive to students’ problems and make it difficult to listen to and endure students’ pain18. Counselors experiencing CF may face physical, psychological, and emotional burnout25.

Counselors do not always experience fatigue, burnout, stress, or CF as a consequence of their service. Counseling has both challenging and rewarding aspects. Therefore, some counselors may feel fulfilled when providing psychological support to students in difficult situations. In other words, counselors can gain inner peace through their work. A counselor who observes that a student’s distress is reduced, their problems are solved, and their pain is alleviated may find greater satisfaction in their professional life. For example, a counselor who plays an active role in protecting the mental health of a self-harming student may feel professional satisfaction by recognizing the importance of their work. Counselors who feel more comfortable mentally and emotionally and appreciate the service and support they provide to students, families, and teachers are more likely to experience CS.

The opposite pole of CF is CS. Therefore, CS can be effective in reducing and preventing CF26. Accordingly, it is important for counselors to experience CS in order to experience less CF. Many factors can influence the reduction of CF or the development of CS. These factors include not only lifestyle practices such as meditation, spirituality-based rituals, nature walks, and balanced nutrition but also individual characteristics such as personality traits, coping strategies, and social support networks, which have been shown to impact resilience and wellbeing23,27. Additionally, self-compassion has been found to be effective in both reducing CF9 and enhancing CS28, highlighting its role as a protective factor in counselors’ occupational wellbeing.

Self-compassion

Self-compassion is defined as the capacity to approach one’s own difficulties, failures, and imperfections with kindness and understanding, recognizing these experiences as an inherent part of the shared human condition29,30. This perspective encourages individuals to treat themselves with the same warmth and empathy they would extend to a close friend in distress, rather than engaging in harsh self-criticism or judgment. Individuals high in self-compassion are more likely to acknowledge their inadequacies without damaging their self-identity, embracing the understanding that imperfection and making mistakes are universal experiences31.

Three components of self-compassion are mentioned. First, when an individual is faced with pain and difficulties, instead of criticizing and judging oneself harshly, he/she shows kindness and understanding towards oneself. Second, instead of isolating oneself by burying oneself in problems and sorrows, the individual perceives these as a common experience of humanity. The third is that the individual is mindful of what he/she experiences and develops a balanced awareness of negative experiences instead of identifying with difficult experiences by making painful feelings and thoughts his/her own identity and self29,30. Self-compassion is an important factor for a person to lead a peaceful life, to have good mental health, and to have functional relationships with people. Self-compassion is an effective variable in one’s ability to struggle with difficulties. Individuals with high levels of self-compassion may also have high levels of well-being32.

Recent research underscores the protective role of self-compassion in helping professions. For instance, Mantelou and Karakasidou33 found that self-compassion among mental health professionals enhanced subjective happiness and improved professional quality of life by mitigating the adverse effects of CF. Similarly, Yu et al.34 demonstrated that self-compassion effectively reduced CF and increased CS in emergency nurses. These findings suggest that self-compassion is likely a crucial resource for counselors, enabling them to navigate the challenges of their profession with greater resilience. When counselors cultivate self-compassion, they may experience reduced stress, fatigue, and burnout associated with CF, while simultaneously deriving greater satisfaction from their compassionate engagement. Consequently, this study specifically posits that self-compassion functions as a critical moderator in the relationship between CF and CS among counselors.

The present study

The counseling process inherently involves compassion, which may expose counselors to experiences such as fear of compassion, CF, and CS depending on the nature of their work35,36. Counselors who consistently demonstrate compassion toward others may also neglect their own needs37. Although compassion extends beyond others to include oneself, many counselors lack awareness of how to practice self-compassion, have limited understanding of its application, or struggle to implement it despite knowing its importance38. This situation may have challenging consequences for counselors, leading to burnout and secondary traumatic stress17,39. Given these concerns, it is crucial to understand and determine counselors’ compassion experiences related to their professional roles.

To address this need, the present study aimed to examine the compassion experiences of psychological counselors by investigating their levels of CF, CS, and self-compassion and the relationships among these variables. Importantly, to our knowledge, no previous studies have examined self-compassion as a moderator of the relationship between CF and CS among Turkish counselors. Addressing this gap, we aimed to explore the moderating role of self-compassion in this relationship to provide insights into protective factors that may support counselor wellbeing in Türkiye.

Self-compassion has been recognized as a component of emotional self-regulation and resilience, which can help individuals manage stress and maintain wellbeing in demanding professional roles29,30. In the context of counseling, self-compassion may reduce the negative impact of CF on CS by allowing counselors to respond to work-related stress with greater emotional balance. Therefore, we expected self-compassion to moderate the relationship between CF and CS among Turkish counselors.

Based on this theoretical framework, the study tested the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H 1)

CF is negatively correlated with CS

Hypothesis 2 (H 2)

Self-compassion is positively correlated with CS.

Hypothesis 3 (H 3)

Self-compassion moderates the relationship between CF and CS.

Method

Participants

A total of 367 school counselors participated in this study, yielding an 87.3% response rate from 420 invitations distributed via email and professional networks. The sample consisted of 191 female (52%) and 176 male (48%) counselors, with ages ranging from 23 to 53 years (M = 36.56, SD = 7.80). Participants were employed across various educational settings: preschools (n = 28, 7.6%), primary schools (n = 94, 25.6%), middle schools (n = 123, 33.5%), high schools (n = 100, 27.2%), and Guidance and Research Centers (n = 22,6%).

Procedure

We began collecting data only after obtaining the necessary approval from the Dicle University Social Sciences and Humanities Ethics Committee, Türkiye (Document Date and Number: 06/08/2024-754978). Participants were recruited via purposeful and snowball sampling. Study inclusion criteria were that participants currently working as a counselor under the Ministry of National Education in Türkiye. For this purpose, we contacted psychological counselors who are members of the Turkish Psychological Counseling and Guidance Association via telephone and social media. We invited the counselors to complete an on-line survey. This process started with a counselor information statement and consent details. Participants confirmed that they voluntarily participated in the study. Informed consent was obtained from the participants. We then presented the counselors with the ASCS, CSS and CFS items. The study took approximately fifteen minutes to complete. The recruitment period was held from August 2024 to October 2024.

Measures

Compassion fatigue scale (CFS): The scale developed by Adams et al.40 and adapted into Turkish by Dinç and Ekinci41 was used to measure participants’ level of CS (e.g., ‘As a result of working with clients, I often feel tired, weak or exhausted’). The scale consisting of 13 items was assessed on a 10-point Likert scale (rarely/never = 1 to very often = 10). Higher scores on the scale indicate higher levels of CF. In this study, the CFS also exhibited good reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.983).

Compassion satisfaction scale (CSS): The scale developed by Nas and Sak42 was used to measure 18 years and older old participants’ level of CS (e.g., ‘I feel good when I fulfill the needs of clients’). The scale consisting of 12 items was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores on the scale indicate higher levels of CS. In this study, the CSS also exhibited good reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.977).

Adult self-compassion scale (ASCS): This scale was developed by Nas43 to determine the self-compassion levels of adult individuals. The scale consists of 12 items (e.g., 'I accept that my difficulties are part of life’). Participants indicate their level of agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Higher scores on the scale indicate higher levels of self-compassion. In this study, the ASCS also exhibited good reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.963).

Data analysis

In the present study, we explored the moderating role of self-compassion in the relationship between CF and CS in counselors. Compassion satisfaction was treated as the dependent variable because it represents the positive dimension of counselors’ professional quality of life and well-being. Prior research emphasizes that increasing CS acts as a protective factor against CF, aligning with the objective to enhance counselor well-being21,26,44. To test the moderating role of self-compassion in the effect of counselors’ CF on CS, we used the bootstrapping technique in Process Macro and conducted regression analysis45. Bootstrapping procedures were used in testing the interaction effect as this method provides robust estimates of standard errors and confidence intervals for interaction terms, enhancing the reliability of moderation analyses in psychological research with moderate sample sizes46.

In order to perform regression analysis, some assumptions such as multicollinearity and sample size are put forward. When there is a high level of relationship between independent variables (r = 0.90 and above), multicollinearity is mentioned and it is recommended that there should not be multicollinearity in order to conduct regression analysis47. Taking this into account, we examined the relationships between the variables and found that the highest relationship was − 0.77 (Table 1). According to this finding, it can be stated that there is no multicollinearity. In addition, predictor and moderator variables were standardized (Z score) to avoid the problem of multicollinearity. One of the assumptions of regression analysis is related to sample size. A formula (N > 50 + 8 m; m = independent variable numbers) suggested by Tabachnick and Fidell48 was used to calculate the sample size. According to this formula and considering two independent variables (CF and self-compassion), the sample size should be more than 66. Because the student rate participating in the study was 367, it can be said that this number is sufficient in terms of sample size. In the analysis phase, we performed correlation analysis for hypotheses H1 and H2 and regression analysis for hypothesis H3. While performing the regression analysis, we used 5000 resampling options with the bootstrap method. Additionally, we took into account the criterion set by MacKinnon et al.49 that the values of the 95% confidence interval (CI) should not include zero (0) values. For the moderating effect, we analyzed with the PROCESS macro in SPSS and used Model 150.

Results

Descriptive statistics and relationships between variables

Table 1 shows the mean, min–max values, standard deviation, skewness-kurtosis values and correlation results of the variables. All correlations were statistically significant (p < 0.01) and the associations between the variables are high. There was a negative high correlation between CF and CS (r = − 0.77, p < 0.01) supporting the hypothesis (H1) that higher levels of self-compassion are associated with lower levels of CF. There was also a positive high level between self-compassion and CS (r = 0.70, p < 0.01) supporting the hypothesis (H2) that higher levels of self-compassion are associated with higher of CS.

Self-compassion as a moderator

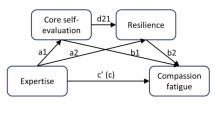

Table 2 shows that self-compassion moderated the relationship between CF and CS, with CF significantly predicting CS (B = − 1.94, 95% CI [− 3.03, − 0.85], p < 0.05). Besides, the self-compassion variable also significantly predicted the level of CS (B = 5.78, 95% CI [4.91, 6.65], p < 0.05). Finally, the interaction of CF and self-compassion variable also significantly predicts CS (B = 6.00, 95% CI [5.21, 6.79], p < 0.05). As illustrated in Fig. 1, the interactively generated variable is significant, and demonstrating the moderating effect of self-compassion variable has a moderator effect (H3).

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the moderating effect of self-compassion on the relationship between CF and CS. According to H1, CF was expected to be negatively correlated with CS. This hypothesis was confirmed as a result of the analysis. There are parallel results with this finding in the literature. Previous studies have found a negative and significant correlation between CF and CS51,52,53,54. Many studies have emphasized the important role of CS in reducing the negative effects of CF55,56. Radey and Figley44 have presented a model for counselors working in the field of mental health to experience CS. In the context of this model, three interrelated approaches are proposed: (1) increasing positive emotions or having a supportive attitude towards clients, (2) improving resources to enhance stress management, and (3) promoting self-care skills44. Counselors who apply this model can prevent the factors that lead to CF while experiencing CS. In order to change CF into CS, it is recommended to organize training programs that include topics such as coping, relaxation, communication skills, taking time for oneself, conducting mindfulness trainings, and organizing improvement programs for those who have problems57. In addition, emphasis is given to the development of mindfulness in counselors. Because it is stated that mindfulness is effective in preventing CF and increasing CS to help experts55.

In the study, H2 was established that self-compassion was expected to be positively correlated with CS. and this hypothesis was supported according to the analysis results. Accordingly, counselors with higher levels of self-compassion have higher levels of CS. CS is the state of satisfaction that counselors achieve while helping clients51. Counselors who provide services to reduce the suffering of clients with psychological problems can feel better mentally by experiencing CS. CS can reduce the cost of caregiving, caring, and compassion in counselors and at the same time decrease the level of burnout52. As a result of self-compassion, counselors can get satisfaction from their work and enjoy providing psychological support to clients. In this context, it is important for counselors working in the field of mental health to learn CS conceptually and to gain awareness about CS. In addition, it is emphasized that counselors should gain experience in self-compassion28. However, in the findings of this study, a negative relationship was found between self-compassion and CF. These results are in parallel with the findings of research on professionals working with people. Previous research has shown that self-compassion is effective on CF9,37,58. The literature on self-compassion has highlighted the potential benefits of self-compassion and its preventive aspect against self-critical attitudes and mental health problems37,59,60. According to these results, self-compassionate counselors may be successful in coping with burnout and fatigue. Being self-compassionate may be beneficial in reducing secondary stress symptoms caused by clients. Consequently, developing self-compassion may be an important preventive factor of CF61.

The results of the study also revealed that self-compassion has a moderating role in the relationship between CF and CS. Therefore, H3 was confirmed. According to H3, self-compassion was expected to moderate the relationship between CF and CS. In other words, the relationship between the CF and CS can be strengthened by the effect of self-compassion. The strength of this relationship may increase especially in individuals with high levels of self-compassion. The self-compassion factor plays an effective role in the relationship between these two variables (CF and CS), making it possible to reduce CF and increase CS. Accordingly, self-compassionate counselors can continue counseling without neglecting their own feelings and needs29,30. In the experience of self-compassion, the counselor is able to perceive the painful and difficult situations not only as something that happens to him/her but also as something that can happen to anyone. This allows counselors to be more resilient in the face of painful and difficult situations, to respond more appropriately to such situations, and to cope with challenging experiences in a healthier way31. Self-compassionate counselors can try to understand the problems that the client reflects in therapy without overly personalizing them. They may get gratification from helping clients and experience CS. Consequently, they may show lower levels of burnout, fatigue and secondary traumatic stress symptoms. In addition, symptoms related to depression and anxiety may decrease with the promotion of self-compassion62.

While these findings align with the existing literature and support the proposed hypotheses, further contextual and practical considerations are essential to fully interpret and apply these results. To deepen the understanding of the observed relationships and to guide future research and practice, it is important to consider the potential influence of the cultural context, the implications of the high correlation between CF and CS, and the practical applications of these findings within the counseling profession.

In the Turkish cultural context, which is characterized by collectivist values and high societal expectations for helping professionals, counselors often prioritize clients’ needs over their own, potentially increasing the risk of CF while striving to maintain CS. Cultural expectations around self-sacrifice and role responsibilities may intensify the emotional demands placed on counselors, thereby influencing the CF-CS relationship. Future studies should continue to explore how cultural factors shape the dynamics of compassion experiences among counselors in Türkiye.

The high negative correlation observed between CF and CS in this study (− 0.77) may suggest a potential conceptual overlap between these constructs. Although such strong correlations are not uncommon in the literature, they should be interpreted cautiously, and future studies may consider utilizing advanced factor-analytic methods to further clarify the discriminant validity of CF and CS measures.

Practical ımplications and ıntervention programs

The findings highlight the need for developing and implementing structured, self-compassion-focused intervention programs and sustainable self-care practices for counselors in Turkey. While mindfulness-based self-compassion training and reflective practices are valuable, additional structured compassion training programs—such as compassion-focused therapy and loving-kindness interventions—can further support counselors in reducing self-criticism, which is a key factor in the development of burnout and stress1,2. Psychoeducational workshops and structured interventions targeting the cultivation of a kinder, more supportive inner dialogue can help counselors manage work-related stress, reduce CF, and enhance CS. Institutions and professional organizations should consider integrating these structured self-compassion practices into counselor training and supervision programs to promote sustainable counselor well-being and professional functioning. Future research should prioritize evaluating the effectiveness of these structured compassion-based interventions within counselor populations to better understand their impact on reducing CF and promoting CS.

Limitations and directions for future research

We believe that the present study has several limitations that should be considered in subsequent research. First, the use of purposive and snowball sampling reduces the generalizability of the findings to larger counselor populations. Future studies should consider employing randomized sampling methods and including individuals with diverse demographic and professional backgrounds to enhance generalizability. Second, the cross-sectional design of the study limits the ability to draw conclusions about the causal direction of the observed relationships. Longitudinal and experimental research designs are recommended to confirm the causal pathways between CF, CS, and self-compassion and to examine these dynamics over time.

Third, the exclusive reliance on self-report measures may introduce biases, including social desirability bias, which is particularly relevant among helping professionals who may feel compelled to present themselves positively. This potential bias could influence the accuracy of the reported levels of CF, CS, and self-compassion. Future research may benefit from incorporating multiple data sources, including supervisor or peer evaluations, behavioral observations, or physiological indicators, to reduce the limitations associated with self-report assessments.

Additionally, while the present study focused on self-compassion as a moderating factor, other potential underlying mechanisms, such as personality traits, social support, and psychological resilience, may contribute to the relationship between CF and CS. Future studies could examine these factors to advance the understanding of the complex interplay between these constructs within the counseling profession.

Overall, this study supports the moderating role of self-compassion in the relationship between CF and CS among counselors. Further research that addresses these limitations will contribute to a deeper and more nuanced understanding of how self-compassion can be effectively cultivated to enhance counselor well-being and professional functioning.

Data availability

All data sets are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- CF:

-

Compassion fatigue

- CS:

-

Compassion satisfaction

- CFS:

-

Compassion fatigue scale

- CSS:

-

Compassion satisfaction scale

- ASCS:

-

Adult self compassion scale

References

Kirby, J. N. Compassion interventions: The programmes, the evidence, and implications for research and practice. Psychol. Pychother. Theory Res. Pract. 90, 432–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12104 (2017).

Gilbert, P. The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 53, 6–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12043 (2014).

Seligman, M. E. P. & Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5 (2000).

Eldor, L. Public service sector: The compassionate workplace—The effect of compassion and stress on employee engagement, burnout, and performance. J. Public Admin. Res. Theory 28(1), 86–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muy029 (2018).

Jazaieri, H. et al. A randomized controlled trial of compassion cultivation training: Effects on mindfulness, affect, and emotion regulation. Motivat. Emot. 38(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-013-9368-z (2014).

Grant, L. & Kinman, G. Enhancing wellbeing in social work students: Building resilience in the next generation. Soc. Work. Educ. 31(5), 605–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2011.590931 (2012).

McCade, D., Frewen, A. & Fassnacht, D. B. Burnout and depression in Australian psychologists: The moderating role of self-compassion. Aust. Psychol. 56(2), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2021.1890979 (2021).

Voon, S. P., Lau, P. L., Leong, K. E. & Jaafar, J. L. Self-compassion and psychological well-being among Malaysian counselors: The mediating role of resilience. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 31, 475–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00590-w (2021).

Upton, K. V. An investigation into compassion fatigue and self-compassion in acute medical care hospital nurses: A mixed methods study. J. Compassion. Health Care 5, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40639-018-0050-x (2018).

Sürücü, A. & Yalçın, A. F. The relationship between personality, self-compassion, and social interest levels of psychological counsellor candidates. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 52(5), 830–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2023.2297894 (2024).

Düşünceli, B., Çolak, T. S. & Koç, M. Empathy levels and personal meaning profiles of psychological counselor candidates: A longitudinal study. J. Theor. Educ. Sci. 14(3), 373–388. https://doi.org/10.30831/akukeg.835056 (2021).

Blake, M. K. Other duties as assigned: The ambiguous role of the high school counselor. Sociol. Educ. 93, 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040720932563 (2020).

Gündüz, B. & Çelikkaleli, Ö. Okul psikolojik danışmanlarında mesleki yetkinlik inancı. Mersin Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 5(1), 119–133. https://doi.org/10.17860/efd.72142 (2009).

Aktan, M. C. Problems that students faced in Turkey and school social work. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. 1(1), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.24289/ijsser.279101 (2015).

Hatunoğlu, A. & Hatunoğlu, Y. Okullarda verilen rehberlik hizmetlerinin problem alanlar. Kastamonu Educ. J. 14(1), 333–338 (2006).

Karataş, Z. & Baltacı, H. Ş. Ortaöğretim kurumlarında yürütülen psikolojik danışma ve rehberlik hizmetlerine yönelik okul müdürü, sınıf rehber öğretmeni, öğrenci ve okul rehber öğretmeninin (psikolojik danışman) görüşlerinin incelenmesi. Ahi Evran Üniversitesi Kırşehir Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 14(2), 427–460 (2013).

Collins, S. & Long, A. Working with the psychological effects of trauma: consequences for mental healthcare workers—A literature review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 10(4), 417–424. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00620.x (2003).

Figley, C. R. Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. J. Clin. Psychol. 58(11), 1433–1441. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10090 (2002).

Arslan, N. Burnout in psychological counselors: An example of qualitative research. OPUS Uluslararası Toplum Araştırmaları Dergisi 8(15), 1005–1021. https://doi.org/10.26466/opus.419320 (2018).

Evans, T. D. & Villavisanis, R. Encouragement exchange: Avoiding therapist burnout. Family J. Counsel. Therapy Couples Families 5, 342–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480797054013 (1997).

Stamm, B. H. The concise ProQOL manual, (2nd Ed.) (2010). https://proqol.org/

Cervoni, A. & DeLucia-Waack, J. Role conflict and ambiguity as predictors of job satisfaction in high school counselors. J. School Counsel. 9(1), 1–19 (2011).

Berzoff, J. & Kita, E. Compassion fatigue and countertransference: Two different concepts. Clin. Soc. Work J. 38, 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-010-0271-8 (2010).

Kelly, L., Runge, J. & Spencer, C. Predictors of compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction in acute care nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 47(6), 522–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12162 (2015).

Showalter, S. E. Compassion fatigue: What is it? Why does it matter? Recognizing the symptoms, acknowledging the impact, developing the tools to prevent compassion fatigue, and strengthen the professional already suffering from the effects. Am. J. Hospice Palliative Med. 27(4), 239–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909109354096 (2010).

Ruiz-Fernández, M. D., Pérez-García, E. & Ortega-Galán, Á. M. Quality of life in nursing professionals: Burnout, fatigue, and compassion satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(4), 1253. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041253 (2020).

Yeşil, A. & Polat, Ş. Investigation of psychological factors related to compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among nurses. BMC Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01174-3 (2023).

Nas, E. A current concept in positive psychology: Compassion satisfaction. Curr. Approach Psychiatry 13(4), 668–684. https://doi.org/10.18863/pgy.852636 (2021).

Neff, K. D. The development of validation of a scale to measure self compassion. Self Identity 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027 (2003).

Neff, K. D. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032 (2003).

Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L. & Rude, S. S. Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. J. Res. Pers. 41(1), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004 (2007).

Neff, K. D. & McGehee, P. Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self Identity 9(3), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860902979307 (2010).

Mantelou, A. & Karakasidou, E. The role of compassion for self and others, compassion fatigue and subjective happiness on levels of well-being of mental health professionals. Psychology 10, 285–304. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2019.103021 (2019).

Yu, H., Qiao, A. & Gui, L. Predictors of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among emergency nurses: A cross-sectional survey. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 55, 100961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2020.100961 (2021).

Er, B. & Ulu, E. Okul psikolojik danışmanlarının şefkat yorgunluğu düzeylerinin duygu düzenleme becerileri ve ruminasyon düzeylerine göre yordanması. Batı Anadolu Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi 15(1), 350–372. https://doi.org/10.51460/baebd.1397503 (2024).

Jalan, K. Current issues of compassion fatigue in counsellor supervision. Int. J. Indian Psychol. https://doi.org/10.25215/1101072 (2023).

Patsiopoulos, A. T. & Buchanan, M. J. The practice of self-compassion in counseling: A narrative inquiry. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 42(4), 301–307. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024482 (2011).

Aruta, J. J. B. R., Maria, A. & Mascarenhas, J. Self-compassion promotes mental help-seeking in older, not in younger, counselors. Curr. Psychol. 42(22), 18615–18625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03054-6 (2023).

Kariuki, J. N., Munyua, J. K. & Ogula, P. Prevalence of compassion fatigue among counsellors in Uasin Gishu County, Kenya. Afr. J. Educ. Sci. Technol. 7(3), 821–825. https://doi.org/10.36347/sjahss.2023.v11i08.004 (2023).

Adams, R. E., Boscarino, J. A. & Figley, C. R. Compassion fatigue and psychological distress among social workers: A validation study. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 76(1), 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.103 (2006).

Dinç, S. & Ekinci, M. Turkish adaptation, validity and reliability of compassion fatigue short scale. Curr. Approach Psychiatry 11(1), 192–202. https://doi.org/10.18863/pgy.590616 (2019).

Nas, E. & Sak, R. Development of compassion satisfaction scale. Electron. J. Soc. Sci. 20(80), 2019–2036. https://doi.org/10.17755/esosder.910301 (2021).

Nas, E. Development of the adult self-compassion scale. Mehmet Akif Ersoy Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Inst. 40, 19–36. https://doi.org/10.20875/makusobed.1453427 (2024).

Radey, M. & Figley, C. The social psychology of compassion. Clin. Soc. Work J. 35, 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-007-0087-3 (2007).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (Guilford Press, 2018).

Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 (2008).

Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS Program (McGraw-Hill Education, 2016).

Tabachnick, B. G. & Fidell, L. S. Çok değişkenli istatistiklerin kullanımı (M. Baloğlu, Çev.). Nobel Akademik Yayıncılık (2015).

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M. & Williams, J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 39(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901 (2004).

Hayes, A. F. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 50(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683 (2015).

Alkema, K., Linton, J. M. & Davies, R. A study of the relationship between self-care, compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnout among hospice professionals. J. Soc. Work End Life Palliat. Care 4(2), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/15524250802353934 (2008).

Grant, H. B., Lavery, C. F. & Decarlo, J. An exploratory study of poliçe officers: Low compassion satisfaction and compassion. Front. Psychol. 9, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02793 (2019).

Slocum-Gori, S., Hemsworth, D., Chan, W. W. Y., Carson, A. & Kazanjian, A. Understanding compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnout: A survey of the hospice palliative care workforce. Palliat. Med. 27(2), 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216311431311 (2011).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, C., Han, X.-R., Li, W. & Wang, Y. Determinants of compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and bur out in nursing: A correlative meta-analysis. Medicine 97(26), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000011086 (2018).

Decker, J. T., Brown, J. L. C., Ong, J. & Stiney-Ziskind, C. A. Mindfulness, compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction among social work interns. Social Work Christian 42(1), 28–52 (2015).

Papazoglou, K., Koskelainen, M. & Stuewe, N. Examining the relationship between personality traits, compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue among police officers. SAGE Open https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018825190 (2019).

Yılmaz, G. & Üstün, B. Professional quality of life in nurses: Compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue. J. Psychiatric Nurs. 9(3), 205–211. https://doi.org/10.14744/phd.2018.86648 (2018).

Beaumont, E., Durkin, M., Hollins Martin, C. J. & Carson, J. Compassion for others, self-compassion, quality of life and mental well-being measures and their association with compassion fatigue and burnout in student midwives: A quantitative survey. Midwifery 34, 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.11.002 (2016).

MacBeth, A. & Gumley, A. Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32(6), 545–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003 (2012).

Wakelin, K. E., Perman, G. & Simonds, L. M. Effectiveness of self-compassion-related interventions for reducing self-criticism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 29(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2586 (2022).

Neff, K. D. The role of self-compassion in development: A healthier way to relate to oneself. Hum. Dev. 52(4), 211–214. https://doi.org/10.1159/000215071 (2009).

Pauley, G. & McPherson, S. The experience and meaning of compassion and self-compassion for individuals with depression or anxiety. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 83, 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608309x471000 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all the counselors who participated or contributed to the current study. Eşref Nas is a psychological counselling and has been working as an assistant professor at the Department of Guidance and Psychological Counseling, Dicle University, Diyarbakir, Türkiye.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EN designed the study, analyzed the results, and wrote the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures for studies involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments or similar ethical standards. Ethical approval was obtained form Dicle University Social Sciences and Humanities Ethics Committee, Türkiye (Document Date and Number: 06/08/2024-754978).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nas, E. Moderating effect of self compassion on compassion fatigue and satisfaction among counselors. Sci Rep 15, 31020 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15732-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15732-z