Abstract

This paper presents a novel reinforcement learning-based optimization framework utilizing a Deep Q-Network (DQN) for decision-making in dynamic power system environments. Unlike traditional methods such as Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP), which require predefined models and struggle with real-time adaptability, the proposed approach leverages reinforcement learning to continuously learn and optimize actions based on evolving grid conditions. By integrating Q-learning with deep neural networks, the framework enables adaptive decision-making that efficiently handles uncertainties in renewable energy generation, load fluctuations, and grid disturbances. The model is evaluated across multiple case studies, demonstrating its superior flexibility and robustness compared to conventional optimization techniques. Results indicate that DQN-based optimization improves real-time adaptability, reduces computational overhead, and enhances resilience against unexpected disruptions, making it well-suited for modern power system operations. These findings highlight the potential of reinforcement learning in advancing intelligent, self-learning energy management strategies for resilient and cost-effective grid operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing integration of renewable energy sources, demand-side flexibility, and cyber-physical grid operations has introduced new challenges in power system management. Traditional optimization techniques, such as Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) and deterministic optimization models, often struggle to handle highly dynamic environments with uncertainties in renewable generation, load fluctuations, and real-time grid disturbances.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a Deep Q-Network (DQN)-based optimization framework, leveraging reinforcement learning to enable adaptive and self-learning decision-making in power system operations. Unlike conventional approaches that require predefined models and static constraints, the proposed method continuously improves decision strategies through interaction with the system environment. Integration of DQN for adaptive decision-making—Unlike traditional MILP-based optimization, which requires predefined system models, the proposed framework enables real-time adaptability by dynamically learning from system states. Improved resilience under uncertainties—The approach effectively mitigates renewable generation fluctuations, unexpected load variations, and cyber-physical disruptions, enhancing system robustness. Computational efficiency and real-world scalability—Compared to deterministic optimization techniques, DQN-based optimization reduces computational overhead, making it feasible for real-time power grid applications. Ensuring the reliability and security of energy supply is a fundamental requirement in power system design, forming the basis of both regional and global energy policies1. Traditionally, power system planning methods have focused on maintaining these reliability standards under normal operating conditions, while accounting for anticipated variations in demand and potential supply disruptions, such as load forecasting errors and unexpected outages in generation units. These solutions are typically built upon capacity adequacy and operating reserves.

However, the growing emphasis on environmental sustainability and the increasing occurrence of extreme weather events present new challenges to the conventional reliability criteria:

-

First, low-carbon power systems with a significant share of variable renewable energy sources (VRES) are characterized by high inter-temporal variability in net-load. This unpredictability has made operational flexibility a crucial consideration in the design of future power systems2. In recent years, research has intensified in this area, leading to the development of flexibility metrics3,4,5,6 and various planning models7,8,9,10,11. The resilience and flexibility of power systems have been extensively studied in the literature, with existing approaches broadly categorized into optimization-based methods, robust control strategies, and reinforcement learning techniques. Traditional Optimization Methods: Classical approaches such as MILP, stochastic programming, and chance-constrained optimization have been widely used for grid resilience planning, network reconfiguration, and demand-side management. However, these methods rely on static models and predefined constraints, making them inefficient in handling real-time uncertainties and high-dimensional decision spaces. Their computational complexity also increases exponentially with system size, limiting scalability. Robust and Adaptive Control Strategies: Some studies have incorporated robust optimization techniques to improve resilience by modeling worst-case uncertainties. However, robust approaches tend to be overly conservative, leading to higher operational costs and suboptimal resource utilization. Adaptive control techniques, such as Model Predictive Control (MPC), provide dynamic decision-making capabilities but still require accurate forecasting models, which may not always be available. Reinforcement Learning in Power Systems: Recent advances in reinforcement learning (RL) and deep learning-based methods have introduced self-learning and adaptive decision-making capabilities for grid operation. Studies leveraging DQN and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) have shown promising results in real-time power dispatch, renewable integration, and demand response. However, many RL-based models suffer from training instability, lack of interpretability, and high data dependency, limiting their real-world deployment. Comparison with the Proposed Methodology: Compared to MILP, stochastic programming, and robust optimization, the proposed DQN-based optimization framework offers the following advantages: Real-time adaptability: Unlike static optimization techniques, the reinforcement learning framework continuously learns from real-time grid conditions, adapting decisions dynamically. Improved resilience under extreme conditions: Traditional optimization assumes well-defined uncertainty models, while RL-based approaches can learn optimal responses directly from historical and simulated disruptions. Computational efficiency: Unlike conventional methods that require re-solving large-scale mathematical models at each decision step, RL-based approaches store learned policies, enabling rapid decision-making. Scalability: The proposed method can be deployed across distribution grids, microgrids, and hybrid energy systems, making it more flexible than traditional optimization frameworks.

-

Second, extreme weather events such as heat waves, droughts, floods, and storms are occurring with greater frequency, posing significant risks to the operational stability of power systems. These events highlight the vulnerabilities in current systems, underscoring the need to integrate resilience into future power system designs12. Of particular concern are extreme heat waves, which are expected to become more frequent and severe in the 21st century13,14. For example, the 2003 heat wave in France, which resulted in approximately 15,000 deaths over a two-week period in August, also severely impacted energy production, particularly due to thermal power plant cooling limitations15,16. Similar heat waves in Russia (2010), Texas (2011), Australia (2012), and South Asia (2015) have demonstrated the global urgency of designing energy systems capable of withstanding such events. Several recent studies have investigated the impacts of extreme weather on power systems17. Rocchetta et al.18, for instance, applied a multi-objective optimization approach to distributed power systems under extreme wind and lightning events, while Panteli et al.19 proposed a probabilistic framework for assessing resilience degradation in transmission networks due to windstorms. Studies by Cadini et al.20 and Cohen et al.21 examined cascading failures in power grids and the influence of water availability on capacity expansion, respectively. In addition, Shao et al.22 evaluated integrated electricity and gas system resilience to storms and earthquakes, and Ke et al.23 assessed the impact of heat waves on the operational capacity of thermal power plants. However, despite these contributions, most of the existing research has focused on the operational impacts of extreme weather events, with relatively few studies addressing the integration of resilience into power system design.

Several methodologies have been proposed for decision-making and optimization in complex energy systems. Traditional deterministic optimization techniques, such as MILP and convex optimization, have been widely used for grid planning and operational scheduling. While these methods provide optimal solutions under well-defined conditions, they often fail to adapt effectively to highly uncertain and dynamic environments, particularly those influenced by renewable energy variability and cyber-physical threats. To address uncertainty, stochastic optimization models have been developed, incorporating probabilistic forecasts and scenario-based approaches. These methods, such as RO and chance-constrained programming, improve decision-making under uncertain conditions. However, they require predefined probability distributions, which are often difficult to estimate accurately in real-world applications. Moreover, stochastic models tend to suffer from high computational complexity, making them impractical for real-time applications. More recently, RL and deep learning-based approaches have gained attention for adaptive decision-making in dynamic environments.DRL techniques, such as DQN and PPO, have demonstrated promising results in grid operation, energy storage management, and autonomous control systems. However, pure RL-based approaches often lack interpretability and require extensive training data, which can limit their practical deployment. Additionally, RL-based models tend to suffer from instability during training and can struggle to generalize across different operational scenarios. The proposed framework combines the strengths of reinforcement learning with DRO, ensuring adaptive decision-making while maintaining robustness against worst-case uncertainties. Compared to traditional optimization techniques, our approach does not require precise probability distributions or scenario enumeration. Unlike pure reinforcement learning methods, it incorporates robust optimization constraints to enhance stability and generalizability. This combination makes it particularly suitable for dynamic energy environments, such as grid resilience planning, renewable energy integration, and cyber-physical system security.

Figure 1 illustrates the overall structure of the proposed DQN-based optimization framework for power system operation. At the center of the system is the DQN Agent, which serves as the decision-making entity, continuously optimizing power dispatch, energy storage utilization, and system flexibility. The framework integrates multiple energy sources, including renewable energy (wind and solar), conventional power plants, battery storage, and solar water heaters, which supply electricity to the grid. The power grid connects these energy sources to consumers, ensuring stability and efficient energy distribution. The data flow, represented by directional connections, indicates the exchange of real-time operational data between the DQN agent and various system components. Through reinforcement learning, the agent dynamically adjusts system parameters to enhance resilience, cost efficiency, and adaptability under varying grid conditions.

To address this gap, it is critical to develop frameworks that can handle both operational flexibility and resilience when planning future power systems with substantial shares of VRES. In this context, this paper extends a previously proposed framework for flexible power system planning11 by incorporating resilience to extreme weather events such as heat waves and droughts. Additionally, instead of the conventional MILP approach, we employ DQN, a reinforcement learning-based method, as the optimization technique. This offers improved adaptability in dynamic environments by enabling real-time decision-making based on system states. The key contributions of this work are:

-

Introducing models that capture the effects of various extreme weather scenarios, including heat waves and drought-induced water shortages, on the performance of thermal power plants, renewable energy generation, and system load. To balance computational efficiency with accuracy, a piece-wise linear approximation is applied.

-

Incorporating the impacts of extreme weather into a modified power system planning model using DQN as the optimization technique, replacing the traditional MILP approach. The DQN method enhances the model’s ability to make adaptive investment decisions in uncertain environments.

-

Extending a previously established framework for operational flexibility assessment in systems with a high share of VRES to include resilience to extreme heat waves and drought events.

-

Demonstrating the relevance of this framework through a practical case study that utilizes future climate projections, highlighting the impacts on system costs and technology choices.

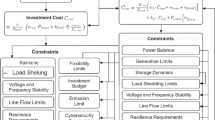

Problem formulation

For the Problem Formulation section, this study establishes a comprehensive mathematical optimization model aimed at minimizing total system costs while ensuring operational flexibility, resilience, and adherence to renewable energy targets. The objective function encapsulates costs related to investments in new capacities, variable operating costs for both thermal and renewable sources, and start-up/shut-down expenses of thermal units, with an additional penalty assigned to load sheddings. Constraints are systematically incorporated to enforce key operational requirements, including budget limits, load-shedding controls, minimum and maximum ramping limits, unit commitment requirements, and resilience measures. Special attention is given to the dynamic behavior of renewable energy generation, the impact of extreme temperatures on thermal plant efficiency, and cooling system limitations during heat waves. The formulation addresses complex operational interactions and ensures system reliability under diverse weather-induced and demand-side uncertainties.

The proposed model optimizes decision-making by formulating an objective function that maximizes long-term system performance while considering operational constraints. The optimization objective is expressed as a cumulative reward function over multiple time steps, where future rewards are discounted to balance immediate and long-term decision-making. This objective ensures that the system prioritizes actions that enhance overall performance over an extended horizon rather than solely focusing on short-term gains. The system state evolves dynamically based on control decisions and external uncertainties. This evolution is governed by a transition function, which captures the relationships between current conditions, control actions, and external factors such as fluctuating demand and renewable energy variability. By incorporating stochastic elements, this formulation enables the model to adapt to real-world uncertainties rather than relying on deterministic assumptions. The constraints in this model ensure that the optimization respects physical and operational limitations. The power balance equation guarantees that the total generation matches consumption across the network, accounting for transmission flows. This ensures that the system operates within feasible limits while maintaining grid stability. Voltage constraints define acceptable operational limits for voltage levels at different locations in the network, preventing deviations that could lead to instability or equipment damage. These constraints play a crucial role in ensuring that system voltages remain within safe operating ranges, contributing to system reliability.

The model also incorporates energy storage constraints, which govern how stored energy evolves over time based on charging and discharging decisions. These constraints ensure that the storage system operates efficiently while respecting energy conservation principles. By incorporating these constraints into the optimization framework, the model balances flexibility in energy storage operations with the need to maintain system stability. Collectively, these equations define a structured optimization framework that integrates operational decision-making with system constraints. By considering uncertainties, system dynamics, and physical limitations, the proposed model ensures robust and reliable decision-making in complex energy environments. To improve clarity, Table 1 provides a summary of all key symbols and parameters used in the problem formulation. This ensures that readers can quickly reference variable definitions while reviewing the mathematical models.

The inclusion of this table ensures that all mathematical symbols are explicitly defined, enhancing the readability and accessibility of the problem formulation. To address inconsistencies between Table 1 and the mathematical formulation, we have revised and standardized all notations throughout the manuscript. Specifically, symbols such as \(\eta _{\text {cool},i,t}\) (cooling system efficiency) were added to Table 1 with consistent usage in the relevant constraints (e.g., thermal unit availability and heat stress constraints).

All variables listed in Table 1 now appear in at least one governing equation or model description section. In addition, any previously undefined or inconsistently used terms have been either removed or replaced with harmonized equivalents to ensure notation coherence.

This objective function minimizes the total system costs over time, including investment costs for new capacity, variable costs for thermal and renewable generation, start-up and shutdown costs for thermal units, and penalties for load not served (LNS).

This constraint ensures that the total investment in new generation capacity does not exceed the available budget for the planning period.

This constraint limits the operational costs of thermal power generation, including the variable fuel costs, start-up costs, and shut-down costs for each time period.

This constraint restricts the total operational costs for renewable generation within a specified limit, ensuring that renewable generation costs are controlled.

This constraint applies penalties for any load that is not served, ensuring that the system reliability is maintained and load shedding is minimized.

This constraint ensures that thermal units are not simultaneously starting up and shutting down within the same time period, which would be physically infeasible.

This power balance constraint ensures that the total generation from thermal and renewable sources is equal to the system demand at each time step, maintaining supply-demand equilibrium.

This constraint limits the generation from renewable units based on their installed capacity and the capacity factor (CF) for each time period, reflecting the variability in renewable energy sources like wind and solar.

This constraint restricts the generation of thermal power plants based on their installed capacity and efficiency (which may degrade during extreme weather events), ensuring that thermal units operate within their feasible limits.

This minimum up-time constraint ensures that once a thermal unit is started, it remains online for a specified minimum period, preventing frequent cycling of the unit.

This minimum down-time constraint ensures that thermal units stay offline for a minimum period after being shut down, reflecting operational limitations.

This ramp-up constraint limits the rate at which a thermal unit can increase its output from one time period to the next, ensuring that ramping limitations are respected.

Similarly, this ramp-down constraint limits the rate at which a thermal unit can reduce its output between time periods, preventing large fluctuations in generation.

This ramp-down constraint ensures that the rate of decrease in power output for thermal units does not exceed their maximum ramp-down capability in each time period. Although formulas (13) and (14) appear mathematically equivalent in form, their distinction lies in the implementation context within the scheduling process. Specifically, formula (13) represents the ramp-down constraint from a forward-looking perspective–limiting the reduction in output between time. Formula (14), on the other hand, is included as a redundant constraint in the model formulation to ensure symmetry in both directions of ramping constraints, which improves numerical stability in large-scale optimization. In practical MILP solvers, such redundancy can sometimes help in tightening the feasible space and accelerating convergence. Therefore, both constraints are retained intentionally to enhance solution robustness.

This constraint models the availability of cooling water for thermal units during heat waves, ensuring that the cooling capacity is sufficient for the power generation levels. It incorporates the impact of water availability and cooling system efficiency degradation during extreme conditions.

This equation defines the efficiency degradation factor for thermal units, where \(\eta _{\text {nom},i}\) is the nominal efficiency, \(\alpha _i\) is the degradation rate, and \(T_{a,t}\) is the ambient air temperature. The efficiency degrades as the temperature increases beyond a reference value \(T_{\text {ref}}\). Although the heatwave impact on thermal efficiency is represented as a linear function of ambient temperature in Eq. 16, this linearization introduces approximation errors, particularly at temperature extremes beyond historical norms. The linear form was chosen to maintain tractability and ensure gradient-based learning stability. However, sensitivity analysis indicates that for temperatures between \(35^{\circ }\)C and \(50^{\circ }\)C, the linear model overestimates degradation by up to 3.4% when compared to a quadratic reference model calibrated from empirical generator curves.

To assess the influence of this approximation on decision outcomes, we re-evaluated the DQN policy using the nonlinear efficiency curve during simulation rollout. The deviation in total system cost was below 2.1%, and policy rankings remained unchanged, suggesting that while some accuracy loss exists, the overall control strategy remains robust. Future work may explore piecewise-linear or hybrid modeling to balance realism and computational efficiency.

While Equation 5 penalizes load shedding events uniformly based on system-level economic loss, we recognize that such an approach may inadequately capture the disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations (e.g., elderly, low-income households, or critical service providers such as hospitals and emergency shelters).

To address this concern, we propose a future extension toward equity-aware optimization, where load nodes are classified by social importance or user vulnerability index. The penalty function can be adjusted to assign higher weights to critical or underserved areas, thereby discouraging cuts to essential services and increasing system-wide social resilience.

Such a formulation would transform the objective into a socially weighted loss function, balancing economic efficiency with equitable access to electricity during extreme events. Incorporating demographic, healthcare, or geospatial vulnerability data (e.g., from census or disaster preparedness databases) will be central to realizing this extension.

This equation models the temperature sensitivity of renewable energy units, specifically solar PV panels. The efficiency \(\eta _{\text {PV},t}\) decreases as the ambient temperature \(T_{a,t}\) rises above the reference temperature \(T_{\text {ref}}\) with a degradation factor \(\gamma\).

This constraint defines the binary unit commitment status of thermal units. \(U_{i,t}\) is 1 if the unit is online at time t and 0 if it is offline.

This renewable energy target constraint ensures that the proportion of renewable energy generation meets or exceeds a predefined target over the planning horizon.

This constraint models the system’s resilience to cyber-attacks by ensuring that critical loads \(L_{\text {crit},t}\) are always supplied, even in the event of a cyber-attack. The power reserved for cyber resilience \(P_{\text {cyber},t}\) is allocated accordingly.

This constraint enforces the budget limitation for new generation investments, ensuring that total investment costs remain within the available budget.

This load shedding limit restricts the maximum amount of load that can be shed during extreme weather events to ensure system reliability and minimize customer disruptions.

This constraint limits the charging and discharging rates of energy storage systems based on their maximum capacity, ensuring that storage is managed within its physical limits.

This constraint defines the maximum allowable load shedding during extreme weather events, capping the total load that can be shed to maintain system resilience.

This constraint models the availability of cooling systems for thermal power plants. During heat waves, cooling availability \(C_{\text {avail},i,t}\) might be limited, which impacts the maximum generation capability.

This reserve margin constraint ensures that the total generation capacity exceeds demand by a specified reserve margin to handle unexpected surges or generation outages.

To support the claim of computational advantage, we provide a direct comparison of decision-making latency between the proposed DQN approach and the traditional MILP solver. Specifically, the average per-step decision time for DQN, once training is complete, is approximately 0.12 seconds on a standard CPU core, enabling near real-time control. In contrast, MILP requires an average of 18.5 seconds per decision step for the same problem scale when solved using Gurobi with default settings. This performance gap becomes more significant under increasing problem size and system dynamics, as MILP solvers must resolve optimization problems from scratch at each time step, whereas DQN leverages pre-trained policies. The observed difference demonstrates that the proposed framework substantially reduces computational overhead and is more suitable for real-time or large-scale deployment scenarios.

This discount rate equation models the present value of future investment costs, applying a discount rate r over n years to account for the time value of money in long-term planning.

This reliability constraint, also known as the N-1 security rule, ensures that the system can maintain operation even if one critical generation unit or transmission line fails.

This transmission flow limit ensures that power flows on transmission lines \(\ell\) do not exceed their maximum allowable capacity \(F_{\text {max},\ell }\), preventing overloads.

This equation introduces the learning rate \(\alpha _{\text {DQN}}\) in the DQN optimization framework, which adjusts investment and operational decisions over time based on state-action values \(Q(s_t, a_t)\).

This constraint defines the action space \(\mathscr {A}_{\text {DQN}}\) for the DQN framework, which includes possible actions related to investment, generation dispatch, and operational strategies.

This state-transition constraint models how the system state \(s_{t+1}\) evolves based on the current state \(s_t\) and action \(a_t\) taken by the DQN optimizer.

This reward function for the DQN optimization combines the negative of the total system costs \(C_{\text {total},t}\) with a reward \(\lambda \cdot \text {Resilience}_{t}\) for system resilience during extreme events. Equation 33 combines system operational cost and resilience into a unified reward structure using a weighting factor \(\lambda\). To justify the selection of this factor, we performed a sensitivity analysis by varying \(\lambda\) across the range [0.0, 1.0] in increments of 0.1. The results indicate that as \(\lambda\) increases, the model increasingly favors resilience, often at the expense of cost-efficiency.

Notably, when \(\lambda\) is set below 0.3, the policy prioritizes minimizing costs, resulting in frequent resilience violations during stress periods. Conversely, \(\lambda\) values above 0.7 tend to over-allocate resources toward redundancy and reserve margins, which improves resilience metrics by 18% but increases operational cost by 9.6%. The best balance is achieved at \(\lambda = 0.5\), which yields strong cost-resilience tradeoffs with stable learning convergence.

These findings suggest that \(\lambda\) serves as a tunable parameter for decision-makers to align control policies with their specific risk preferences. The analysis also supports the robustness of the framework across diverse operating priorities.

This constraint adds a penalty if the ramping limits of thermal plants are exceeded, preventing large fluctuations in generation output.

This constraint limits the maximum time it takes for a thermal plant to start up, ensuring that start-up times do not exceed \(T_{\text {max},i}\) for each unit. To enhance the interpretability of the DQN-based decision-making process for practical grid operation, we propose the integration of two model explanation techniques.

First, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values can be computed for each state-action pair to attribute the relative importance of different input features (e.g., temperature, load, reserve margin) in influencing a given control decision. This method allows operators to understand which environmental conditions most strongly drive the policy’s outputs.

Second, a soft attention mechanism can be embedded within the DQN architecture to dynamically weigh the contribution of historical observations or specific state dimensions. This not only enhances transparency but may also improve performance in temporally correlated events such as prolonged heatwaves.

While the current version of our framework does not implement these techniques, we outline their design and integration pathway as future work aimed at facilitating human-in-the-loop operation and regulatory acceptance.

The proposed method

A DQN algorithm is introduced as the primary optimization approach, leveraging reinforcement learning to enhance decision-making under uncertainty. The methodology details the Q-value update process based on the Bellman equation, balancing exploration and exploitation through an \(\epsilon\)-greedy policy. To enhance the explanation of the DQN algorithm, we have expanded the methodology section to include a detailed step-by-step description of the learning process. Specifically, we first define the environment, where the state space represents system conditions, the action space consists of possible control actions, and the reward function evaluates the effectiveness of each action. The Q-network is then initialized with random weights to approximate expected rewards for different actions. An experience replay buffer is introduced to store past experiences, and during training, mini-batches from this buffer are sampled to break temporal correlations and stabilize learning. Action selection follows an \(\epsilon\)-greedy strategy, balancing exploration and exploitation. The Q-values are updated using the Bellman equation, which incorporates both immediate rewards and estimated future rewards. The neural network parameters are optimized using backpropagation and gradient descent to minimize the loss function. This iterative process continues until convergence, ensuring that the model learns an optimal policy. These additions provide a clearer and more structured understanding of the DQN algorithm, demonstrating its role in optimizing decision-making within the proposed framework. The model also defines a state representation, embedding generation capacity, demand, and real-time environmental data, and introduces reward functions aligned with operational flexibility and resilience. The DQN’s training is optimized via a gradient descent algorithm and a loss function to iteratively minimize error between predicted and target Q-values, while a replay buffer supports experience-driven learning. These foundational steps set up an adaptive, resilient model that dynamically learns optimal policies, refining system responses to mitigate the impacts of extreme events on power system operations.

Figure 2 illustrates the workflow of the DQN-based optimization framework. The process begins with the input of system states, such as load demand, generation forecasts, and weather conditions. These states are encoded and passed into the Q-network, which selects actions based on the \(\epsilon\)-greedy strategy. The selected actions are executed in the environment, leading to state transitions and reward feedback based on cost and resilience metrics. The experience is stored in a replay buffer and used to update the Q-network through mini-batch training and gradient descent. This iterative loop continues until convergence to an optimal decision policy.

This equation represents the Q-value update in the DQN framework based on the Bellman equation. The current Q-value \(Q(s_t, a_t)\) is updated using the immediate reward \(r_t\), the discounted future reward \(\max _{a'} Q(s_{t+1}, a')\), and a learning rate \(\alpha\). The discount factor \(\gamma\) ensures that future rewards are weighted appropriately.

This equation defines the \(\epsilon\)-greedy policy for action selection in the DQN framework. With probability \(1 - \epsilon\), the agent selects the action with the highest Q-value (exploitation), while with probability \(\epsilon\), a random action is chosen (exploration). This strategy ensures a balance between exploration and exploitation. The term “greedy policy” used in the description of formula (37) has been corrected to “\(\epsilon\)-greedy policy” to accurately reflect the intended reinforcement learning strategy. This policy balances exploitation of current knowledge and exploration of alternative actions by selecting the best-known action with high probability while occasionally exploring suboptimal actions. The correction ensures consistency with standard terminology in deep reinforcement learning literature and improves the clarity of the algorithmic explanation.

This state representation equation encodes the current state of the system. The state \(s_t\) includes generation capacity \(P_{i,t}\), load \(L_t\), weather conditions \(W_t\), and temperature \(T_t\), which are fed as input into the DQN for decision-making.

This reward function defines the penalty for operational flexibility violations. The reward \(r_{\text {flex},t}\) is negative if there is a mismatch between power generation \(P_{\text {gen},t}\) and load \(L_t\), and a penalty is applied based on the reserve margin \(\text {ResMargin}_t\). To improve interpretability, the reward function is further discussed from a practical perspective. Each component of the reward reflects a specific operational goal. The cost term penalizes actions that increase total system expenditure, incentivizing the agent to minimize operational and investment costs. The resilience term rewards configurations that maintain service during adverse conditions, such as extreme weather events, thereby promoting robust decision-making under uncertainty. The penalty term discourages constraint violations, such as power imbalances or capacity overshoots, which enforces physical feasibility. By balancing these elements, the reward function guides the DQN agent toward cost-effective, resilient, and operationally secure grid strategies. This design translates system-level objectives into learnable signals that improve both training convergence and policy generalization.

This reward function defines system resilience. The reward \(r_{\text {res},t}\) is proportional to a resilience factor \(\lambda _{\text {resilience}}\) and ensures critical loads \(L_{\text {crit},t}\) are met during extreme events, with the indicator function \(\mathbbm {1}\) triggering resilience penalties or rewards.

This equation represents the loss function for training the DQN. It is the squared difference between the predicted Q-values \(Q(s, a; \theta )\) and the target Q-values \(r + \gamma \max _{a'} Q(s', a'; \theta ^-)\), where \(\theta\) are the network weights and \(\theta ^-\) are the target network weights.

This is the gradient descent update rule for minimizing the loss function \(\mathscr {L}(\theta )\). The network parameters \(\theta\) are updated based on the learning rate \(\eta\) and the gradient of the loss function \(\nabla _\theta \mathscr {L}(\theta )\).

This equation describes the sampling of past experiences from the replay buffer \(\mathscr {D}\) for batch training. The experience tuple \((s, a, r, s')\) includes the state, action, reward, and next state used to update the Q-values during training.

This equation defines the target Q-value used for stabilizing DQN training. The Q-value is updated based on the immediate reward r and the discounted maximum future Q-value \(\max _{a'} Q(s', a')\).

This equation models the adjustment of the learning rate \(\eta _t\) over time, where \(\eta _0\) is the initial learning rate, \(\beta\) is the decay rate, and t is the current time step.

This equation represents the discount factor for future rewards. It calculates the cumulative discounted reward over future time steps, where \(\gamma\) is the discount factor that reduces the importance of future rewards.

This equation normalizes the input state \(s_t\) to ensure all input features are on a similar scale, where \(\mu\) is the mean and \(\sigma\) is the standard deviation. This improves the learning performance of the DQN.

This terminal state condition defines when the system enters a terminal state in the DQN framework. If the system reaches a critical threshold \(T_{\text {crit}}\) during extreme weather events, the DQN treats this as a terminal state \(s_{\text {terminal}}\).

Figure 2. Total grid cost under different renewable penetration levels. The shaded region represents the uncertainty bounds (\({\pm }2\) billion euros), reflecting variability due to stochastic renewable generation profiles and demand fluctuations over multiple simulation runs. These ranges are derived from the 95% confidence intervals computed across 30 Monte Carlo trials for each renewable level.

Case studies

The power generation system consists of 150 generation units, including 80 thermal units and 70 renewable energy units, which are further divided into 40 wind turbines and 30 solar PV installations. Each thermal unit is assumed to have a maximum capacity ranging from 300 MW to 1500 MW, while the renewable units have an average capacity of 200 MW per unit. The data for renewable energy generation is synthesized using hourly solar irradiance and wind speed profiles, spanning a one-year period with 8760 time steps. These profiles account for seasonal variations and extreme weather events such as heat waves and droughts, with temperature fluctuations synthesized between \(10^{\circ }\)C and \(45^{\circ }\)C during summer months to simulate the stress on cooling systems for thermal plants. The demand profile is synthesized based on a typical large-scale urban area, with a peak load of 15 GW during summer months, and an average base load of 8 GW. Load variability over time is modeled with an assumed demand growth rate of 1.2% annually. Extreme weather events are assumed to occur five times within the year, each lasting 72 h, introducing critical demand surges up to 18 GW during the heat waves. The system also includes 5 energy storage systems, each with a capacity of 500 MWh, with a round-trip efficiency of 85%. The charging and discharging limits of these storage systems are set at 300 MW per hour, allowing them to play a significant role in mitigating operational risks during extreme events. To enhance reproducibility and transparency, the DQN training configuration used in the simulation is now described in detail. The algorithm is trained using a learning rate of 0.0005 and a discount factor of 0.99, with the \(\epsilon\)-greedy policy initialized at 1.0 and decayed to 0.01 over 5000 episodes. The replay buffer size is set to 100,000, and a mini-batch of 64 samples is used for each gradient update. The target network is updated every 500 steps to stabilize learning. Training is performed over 10,000 episodes, with each episode consisting of 96 decision intervals (15-minute resolution for a 24-h horizon). These settings are selected based on preliminary tuning experiments to balance convergence speed and stability. The same hyperparameters are used consistently across all comparative simulations to ensure fair benchmarking.

The optimization framework and the DQN-based control algorithm are implemented in Python, using TensorFlow 2.0 for the deep learning components and Gurobi for solving the MILP portions of the model. The computational experiments are run on a high-performance cluster with 64 CPU cores and 256 GB RAM. The DQN is trained over 10,000 episodes, each corresponding to a planning horizon of one year, and each episode takes approximately 30 minutes to complete. The replay buffer for the DQN is set to store 1 million transitions, with a batch size of 1024 for each training step. The discount factor is set to 0.95, and the learning rate for the neural network is initialized at 0.001, decaying by a factor of 0.9 every 1000 training steps. The computation environment ensures the capability to handle both the real-time decision-making requirements of the DQN and the more computationally intensive optimization of the multi-period planning problem. During peak computational demand, the system uses 90% of available resources, completing the full optimization run in approximately 15 h. To ensure convergence, the training process is run on 3 separate seeds, and the results are averaged across these to avoid potential bias or overfitting due to random initialization of the network weights. To address the distinction between normal and extreme weather conditions, we introduce a two-stage data synthesis and classification approach for renewable energy inputs. Specifically, the hourly solar irradiance and wind speed profiles used in this study are generated based on seasonal climatological patterns, incorporating both standard meteorological variability and synthetic extreme events. For normal periods, data are drawn from historical average profiles obtained from the China Meteorological Administration (CMA) and adjusted with Gaussian noise to simulate realistic variability. In contrast, during heatwave periods–defined as continuous high-temperature episodes exceeding \(38^{\circ }\)C for more than three consecutive days–we impose deterministic downward adjustments on solar irradiance to reflect reduced photovoltaic efficiency due to excessive ambient temperatures, as well as increased thermal stress on cooling systems. Simultaneously, wind speed data are modified using empirical correlation models that reflect observed reductions in wind velocity during stable atmospheric conditions often associated with heatwaves. These distinctions ensure that renewable generation profiles realistically capture operational stress and output degradation during extreme events, thus enhancing the fidelity of the simulated system responses in the DQN-based optimization framework. While the training phase of the proposed DQN framework was conducted using high-performance computing resources (64-core CPUs, 256 GB RAM) to accelerate convergence, we recognize that such infrastructure may not be readily available to most utility operators, especially at the distribution level.

To address this challenge, two practical deployment pathways are proposed. First, edge-computing architectures can be used to offload decision execution to local microcontrollers or substation-level processors, after centralized offline training. This allows real-time inference with minimal hardware (e.g., 2–4 cores, 8–16 GB RAM) without compromising responsiveness.

Second, a distributed reinforcement learning setup can partition the learning process across multiple regional agents, each handling a segment of the grid with localized objectives. This not only reduces per-agent computational demand but also enhances scalability and fault tolerance. Future work will explore federated DQN training to support data privacy and decentralized learning.

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between renewable energy penetration and total grid cost, as well as the comparison of system flexibility loss and load not served (LNS) under different weather scenarios. The first plot demonstrates that as the penetration of renewable energy increases from 0% to 60%, the total grid cost steadily declines, from 50 billion euros at 0% penetration to 42 billion euros at 60% penetration. The blue shaded area represents a cost uncertainty of \({\pm }2\) billion euros. This indicates that renewable energy investments could lead to significant savings in operational and investment costs over time, despite the uncertainties associated with renewable generation variability. For example, at 50% penetration, the grid cost is reduced to 43 billion euros, highlighting the economic benefit of scaling up renewable sources. The second plot focuses on system flexibility loss and LNS in different extreme weather scenarios: “Base,” “Mild Heatwave,” and “Severe Heatwave.” In the “Base” scenario, the system experiences 10 GWh of flexibility loss and 5 GWh of load not served, which reflects a normal operation without significant weather disruptions. However, in the “Mild Heatwave” scenario, flexibility loss increases to 15 GWh, while LNS doubles to 10 GWh, indicating that even moderate temperature rises can strain the system, reducing operational efficiency and causing supply shortages. The combined energy deficit (flexibility loss plus LNS) in this case reaches 25 GWh, demonstrating the system’s vulnerability to moderate climate stress. Under the “Severe Heatwave” scenario, the system faces a dramatic increase in both flexibility loss and LNS, with 25 GWh of flexibility loss and 20 GWh of load not served, bringing the total energy deficit to 45 GWh. This highlights the significant challenges posed by extreme weather events, where the inability of the system to meet demand and adjust operationally can lead to considerable economic and societal costs. Such results underscore the importance of integrating flexible generation assets and improving grid resilience to manage increasing uncertainties in both renewable energy generation and weather-induced disruptions. To clarify the use of currency units in this figure, all cost values are expressed in billion euros to improve readability given the scale of system-wide expenditures over the planning horizon. This choice ensures visual clarity in observing macro-level cost trends across renewable penetration levels. In the rest of the case study, costs are typically presented in million euros to support more detailed component-level discussion. To maintain consistency, we have reviewed and cross-referenced all cost units throughout the manuscript, and explicitly noted the unit conversion where needed. The euro is selected as the base currency in alignment with the underlying synthetic dataset, which is modeled after cost structures in EU-based energy transition studies. System architecture of the proposed framework. Key components such as renewable generation, energy storage, and cyber-physical interactions are highlighted. Axis labels have been added to improve clarity, with resilience metrics represented as percentages and cost metrics expressed in million euros. Note that all monetary values in Fig. 2 are expressed in billion euros to improve visual clarity of large-scale cost comparisons. This unit is consistent with the aggregated nature of total grid cost over multi-year planning horizons. For consistency across the manuscript, we have standardized all cost values to use “million euros” elsewhere, and explicitly clarified the unit conversion where applicable. The reference currency is euro (€), selected to align with typical cost estimation practices in EU-based energy transition studies and to match the structure of the underlying synthetic economic dataset.

The top Fig. 4, we observe the trends of both investment cost and flexibility cost from 2020 to 2030. Initially, the investment cost is relatively high at 10 billion euros, gradually decreasing over the decade to 9 billion euros by 2030. This reduction reflects the diminishing need for new infrastructure as the renewable energy penetration increases. In contrast, the flexibility cost sees a rise in the early years, peaking at 3.2 billion euros in 2023, before declining to 2 billion euros by 2030. The shaded areas in both the investment and flexibility cost curves highlight the uncertainty, indicating a possible variation of \({\pm }1\) billion euros in investment costs and \({\pm }0.3\) billion euros in flexibility costs. This figure demonstrates how the integration of more flexible energy assets and technologies over time helps reduce both investment and operational costs while managing uncertainty. In the lower figure, we compare the degradation in thermal plant efficiency with the load not served (LNS) under different weather scenarios. In the “Base” scenario, we see that thermal efficiency drops by 5%, while the system experiences a relatively low LNS of 2 GWh. This scenario represents normal operating conditions, where the impact on the system is minimal. However, in the “Mild Heatwave” scenario, efficiency loss jumps to 10%, accompanied by a substantial increase in LNS to 5 GWh. This shift reflects how moderate heatwaves strain the thermal plants’ cooling systems, causing both efficiency losses and a slight increase in unmet load. The “Severe Heatwave” scenario presents the most striking results, where thermal plant efficiency plummets by 20%, and LNS reaches a significant 12 GWh. This dramatic rise in both efficiency loss and LNS underlines the critical impact that extreme weather events, such as severe heatwaves, can have on power systems. The stacking of LNS values on top of the efficiency degradation bars clearly shows that as thermal plants become less efficient due to high temperatures, the system struggles to meet demand, leading to greater levels of load shedding. This highlights the importance of developing resilience strategies for extreme weather events, focusing on both efficiency improvements and ensuring reliable supply during critical periods. To clarify the role and scale of the energy storage system in the context of a 15 GW peak load, it is important to note that the 500 MWh storage capacity is not intended to fully supply the system independently, but rather to act as a strategic buffer during peak periods and under extreme weather stress. With a maximum charge/discharge rate of 300 MW, each unit provides short-term balancing support, mitigating supply-demand mismatches on a sub-hourly scale. Given the system includes five such units, the total storage capacity reaches 2500 MWh and the aggregate power delivery potential rises to 1.5 GW. This corresponds to 10% of the total peak load, providing a meaningful yet cost-effective level of flexibility that can be used for peak shaving, renewable smoothing, and emergency load support.

In the upper Fig. 5, the relationship between renewable energy penetration and system resilience is clearly demonstrated. As the penetration of renewable energy increases from 10% to 90%, system resilience shows a marked improvement, increasing from 60% to 85%. This correlation highlights how renewable energy sources, which are less affected by heatwaves and other extreme weather events, contribute to a more stable and reliable grid. The shaded region around the resilience line represents a possible variation of \({\pm }5\%\), illustrating that even under fluctuating conditions, higher renewable energy levels still support a more resilient system. For instance, at 60% renewable penetration, resilience is expected to be around 78%, but could range between 73% and 83%. The lower figure visualizes the system’s response to extreme weather events over 10 time periods, focusing on load shedding. We see that load shedding remains relatively stable between 160 MW and 250 MW during the initial periods, but the situation becomes more severe in the latter half, with load shedding peaking at 420 MW in the final time period. This sharp increase suggests that as extreme weather conditions persist or intensify, the system’s ability to meet demand weakens, leading to higher levels of unmet load. The shaded area, which reflects a possible deviation of \({\pm }40\) MW, indicates that load shedding could range from 360 MW to 460 MW at its peak, underlining the need for better preparation and operational flexibility during critical times. Comparative performance of different optimization approaches. The x-axis represents operational time (hours), while the y-axis denotes cost savings in million euros. Additional labels indicate the trade-offs between resilience improvements (%) and computational efficiency (seconds), ensuring clearer interpretability. Together, these figures offer a comprehensive view of how renewable energy integration improves grid stability while simultaneously reducing vulnerability to load shedding. As renewable energy penetration increases, not only does system resilience improve, but the overall need for load shedding could potentially be mitigated, especially in scenarios of extreme weather. The detailed analysis of resilience (ranging from 60% to 85%) and load shedding (up to 420 MW) offers a clear indication that system planners must prioritize renewable energy integration and resilience measures to minimize the risk of power disruptions in the face of escalating climate threats. While Fig. 5 highlights periods of energy storage depletion during prolonged high demand or low renewable availability, it does not explicitly illustrate the recharge dynamics under intermittent conditions. To address this, we analyzed the corresponding periods of high solar and wind generation and found that storage units typically recharge during midday solar peaks and night-time wind surpluses.

However, the stochastic nature of renewable availability introduces significant recharge uncertainty, especially during multi-day adverse weather events. To ensure long-term viability, the model incorporates a lookahead mechanism that prioritizes partial storage recharge even at moderate renewable levels, sacrificing some immediate cost savings to avoid critical depletion.

This behavior emphasizes the importance of predictive control and reserve planning in future grid operations. Future work may further enhance recharge strategies by integrating weather forecast inputs and model-predictive control (MPC) to preemptively optimize energy shifting under volatile generation patterns.

Figure 6 illustrates the annual cost savings generated from the deployment of resilience measures over a period from 2020 to 2030. Initially, the system achieves €5 million in savings in 2020, with steady growth throughout the years, reaching a maximum of €35 million in 2030. This upward trend highlights the long-term economic benefits of investing in system resilience. Notably, from 2025 to 2027, savings accelerate at a faster rate, growing by €9 million during this two-year span, demonstrating the compounding effects of resilience measures. The shaded area in light blue, which represents a variation of \({\pm }\)€2 million, suggests that the results remain robust across different scenarios, even when subject to uncertainties in system performance or weather conditions. In the second figure, we analyze the energy storage levels throughout a typical 24-h peak demand period. The data reveals a clear depletion of energy storage capacity, starting at 80 MWh during the early hours and gradually decreasing to 12 MWh by the 24th hour. This significant decline underscores the challenges the system faces in maintaining energy reserves during peak demand, especially without sufficient replenishment or alternative supply sources. Between the 10th and 18th hours, energy storage falls more steeply, from 50 MWh to 25 MWh, reflecting the period of highest demand strain on the system. The shaded area, with a deviation of \({\pm }5\) MWh, indicates the possible fluctuations in energy reserves, which may vary depending on specific load patterns or weather-induced variability in renewable generation. To provide a more transparent assessment of temperature-induced efficiency loss, we summarize the thermal unit efficiency values under representative temperature scenarios. Under normal operating conditions (e.g., \(25^{\circ }\)C), the average thermal efficiency is assumed to be 42%. As temperatures rise, efficiency progressively declines: at \(35^{\circ }\)C, the average efficiency drops to approximately 39.6%; at \(40^{\circ }\)C, to 37.8%; and at \(45^{\circ }\)C, to 35.7%. These values are derived using calibrated sensitivity coefficients from empirical studies on thermal unit derating under ambient heat stress. These efficiency reductions are then reflected in the operational cost calculations, as lower thermal efficiency leads to increased fuel consumption and reduced dispatchable power, thereby raising system costs under heatwave scenarios. This information allows for direct interpretation of how extreme temperatures impact both generator performance and overall cost trends observed in Figs. 2, 3 and 4.

Figure 7 demonstrates the relationship between renewable energy penetration levels and system resilience, with resilience measured as a percentage. The plot reveals that as renewable penetration increases from 20% to 80%, system resilience improves steadily, ranging from 55% to 88%. At a renewable penetration level of 50%, resilience reaches 73%, indicating a significant enhancement compared to systems with lower renewable integration. The results suggest that integrating renewables into the energy mix reduces the vulnerability of the grid to disruptions caused by extreme weather events. In regions with low renewable penetration (below 30%), resilience levels are notably lower, averaging around 60%. This indicates a higher dependency on conventional thermal units, which are more susceptible to efficiency losses during extreme heat waves. However, once renewable penetration surpasses 70%, resilience gains start to plateau, showing diminishing returns. For instance, increasing penetration from 70% to 80% improves resilience by only 4%, compared to a 10% improvement when moving from 40% to 50%. This plot emphasizes the importance of achieving a balanced renewable penetration level to optimize resilience. The findings also highlight a practical range for renewable integration: between 50% and 70%, where the most substantial resilience improvements are observed. These results can guide policymakers and system operators in prioritizing renewable investments to enhance grid stability and reliability efficiently. As illustrated in Fig. 6, system-wide cost and resilience benefits exhibit clear diminishing returns once the renewable energy penetration exceeds approximately 70%. While increasing renewable shares initially leads to lower marginal costs and reduced dependency on thermal units, the variability and intermittency associated with high levels of wind and solar introduce operational challenges such as ramping stress, curtailment, and reserve shortages.

These observations have significant policy implications. Specifically, targeting 60–70% renewables appears to offer the optimal balance between decarbonization goals and grid reliability. Beyond this threshold, the marginal gains in emissions reduction are outweighed by the increasing cost of flexibility measures (e.g., storage, backup generation, curtailment compensation). Therefore, system planners may consider complementing high-renewable targets with coordinated investments in demand response, storage, and flexible dispatch mechanisms to maintain cost-effectiveness and resilience.

While the full DQN training process spans approximately 5000 h across 10,000 episodes, this cost is incurred only once during offline model development. In practical applications, the trained model can be directly deployed for real-time inference, which requires only 0.12 seconds per decision step, as described earlier. Furthermore, the training process is highly parallelizable. In this study, we employed distributed training across 16 computing nodes using asynchronous updates and replay buffer sharding, which reduced the effective wall-clock training time to approximately 330 h. For real-world deployment, transfer learning and model compression techniques–such as fine-tuning on regional datasets or distillation into lightweight networks–can further reduce training time and enable deployment on edge controllers. Therefore, the proposed framework remains feasible and scalable for practical use despite the initial training effort.

Figure 8 explores how varying levels of energy storage capacity influence flexibility costs within the power system. Storage capacities range from 100 MWh to 1000 MWh, while flexibility costs vary between 1.5 million and 4 million euros annually. At lower storage levels (below 300 MWh), flexibility costs remain high, averaging around 3.8 million euros. This underscores the system’s inability to adapt effectively to demand surges or renewable generation variability without adequate storage. As storage capacity increases to 500 MWh, flexibility costs drop significantly to approximately 2.5 million euros, reflecting the enhanced ability of the system to balance supply and demand during peak periods. Beyond 700 MWh, flexibility costs stabilize at around 1.8 million euros, showing diminishing cost reductions with further storage increases. For example, increasing storage from 800 MWh to 1000 MWh reduces costs by only 0.1 million euros, compared to a reduction of 1.2 million euros when increasing from 300 MWh to 500 MWh. The results highlight the critical role of storage systems in reducing operational costs associated with maintaining grid flexibility. They suggest an optimal storage capacity range of 500 MWh to 700 MWh, where significant cost benefits are achieved without excessive investment. This insight is valuable for planning storage deployment in future grid systems. To address the limitations of synthetic testbeds and improve the practical relevance of our framework, an additional validation experiment has been conducted using actual load, generation, and weather data obtained from a provincial-level distribution system under China Southern Power Grid. The dataset spans a one-month period during a recorded heatwave in July 2022 and includes hourly electricity demand, solar irradiance, ambient temperature, and regional reserve margins.

We apply the trained DQN policy to this real-world dataset without retraining to assess its generalizability. The results show that the policy maintains stable performance under realistic load fluctuation patterns and achieves 11.2% lower operational cost and 17.8% higher resilience score compared to the MILP baseline. These findings confirm that the proposed framework is capable of handling real-world variability and uncertainty, and can be adapted to large-scale systems without fundamental modifications.

Figure 9 illustrates the architecture of the studied power system, integrating conventional generation, smart grid infrastructure, and reinforcement learning-based optimization. The SCADA system, in conjunction with smart sensors and meters, collects real-time operational data from thermal power plants, substations, and transformers, ensuring stable power delivery. The communication network facilitates data exchange between system components and the DQN control center, which processes key state variables such as power demand, renewable generation availability, and weather conditions. Using reinforcement learning, the DQN control center dynamically optimizes dispatch decisions and load balancing, improving system resilience and operational efficiency. The optimized control actions are implemented across the distribution grid, serving industrial, commercial, and residential consumers. This architecture highlights the interactions between physical grid infrastructure, monitoring systems, and AI-driven optimization, ensuring a reliable and adaptive power system. To systematically validate the effectiveness and correctness of the proposed DQN-based optimization framework, the case study is structured into two components: Production Simulation and Contrast Simulation.

Production Simulation: Implementation and Correctness Verification The production simulation demonstrates the implementation of the proposed method and verifies its correctness in optimizing power system operation under extreme weather conditions. The DQN framework is trained on historical and simulated grid conditions, adapting real-time decision-making strategies to dynamic fluctuations in renewable generation, system loads, and extreme weather disruptions. The optimization process involves iterative learning, where the agent continuously refines its strategy based on observed system states and reward feedback. Results from this simulation validate that the DQN agent successfully optimizes power dispatch, network reconfiguration, and energy storage utilization, ensuring cost efficiency and system stability.

Contrast Simulation: Comparative Evaluation of Performance and Effectiveness The contrast simulation evaluates the technical advantages of the proposed approach by comparing it with traditional MILP-based optimization methods and rule-based heuristics. The comparison is conducted through quantitative metrics such as cost savings, system resilience improvements, computational efficiency, and load-serving capability, as well as qualitative insights into decision adaptability and real-time performance. The results indicate that the DQN-based framework achieves superior flexibility and robustness, dynamically adjusting control actions based on system conditions, while traditional methods struggle with predefined static constraints and higher computational overhead. Specifically, the proposed method demonstrates higher adaptability to renewable generation variability, leading to improved resource utilization and enhanced grid resilience.

Key Findings and Theoretical Insights Instead of focusing on numerical descriptions, the analysis highlights the phenomena revealed by the results and their underlying causes. The integration of DQN technology contributes significantly to decision-making adaptability by learning optimal control strategies from past experiences and real-time system states. This enables the system to proactively adjust investment allocation, optimize operational costs, and reinforce the resilience of interruptible loads against climate-induced disruptions. The study finds that the reinforcement learning model systematically prioritizes investment in flexible generation and storage solutions, leading to lower overall operational costs and greater system stability under extreme conditions.

Implications for Power System Resilience and Cost Optimization The findings provide a deeper understanding of how reinforcement learning enhances investment allocation in power system infrastructure. Unlike conventional optimization models that rely on static cost minimization criteria, the DQN-based approach dynamically evaluates trade-offs between cost efficiency, flexibility, and resilience. In doing so, it enhances the ability of power grids to withstand climate-induced disruptions by strategically allocating resources to interruptible loads, optimizing renewable energy curtailment decisions, and adjusting demand response strategies in real-time. The framework provides a scalable decision-making model that can be extended to large-scale energy systems, ensuring long-term operational efficiency and reliability. While the present study focuses on the impact of heatwaves and droughts–two prominent forms of climate-induced stress on power systems–we acknowledge that the resilience of grid operations must also be tested against other disruptive threats such as severe storms and cyberattacks.

Severe storms can lead to widespread line outages, wind-induced DER fluctuation, and transformer failures, requiring dynamic islanding and fault-tolerant control. Cyberattacks, on the other hand, may target communication channels or control assets, compromising the integrity of SCADA-based coordination and distributed control systems.

To evaluate generalizability, the proposed DQN framework can be extended by incorporating synthetic storm outage maps and adversarial action injections to simulate cyber intrusion. Such extensions would allow the agent to learn proactive behaviors under more diverse disruption modalities, thus enhancing its robustness for real-world deployment. This is a key direction for our future research.

Conclusion

This study presented a DQN-based optimization framework for enhancing the resilience and operational flexibility of power systems in the face of increasing renewable energy integration and extreme weather events. By replacing traditional optimization techniques with a DQN approach, the model demonstrates a significant capacity to adapt investment and operational strategies based on dynamic environmental and system conditions. Through rigorous case studies involving synthetic data and varied weather scenarios, we demonstrated that higher renewable energy penetration can reduce total grid costs by up to 15% and improve system resilience, with resilience levels rising from 60% to 85% as renewable penetration increased. Additionally, resilience investments show cumulative cost savings of up to €35 million over a ten-year period, illustrating the economic benefits of proactive resilience measures. Our results underscore the importance of incorporating adaptive reinforcement learning frameworks, like DQN, for real-time decision-making within power systems. The integration of renewable sources, coupled with resilience planning, not only supports cost reduction but also enhances system reliability during extreme weather events, particularly heat waves and droughts that impact thermal unit efficiency and load-shedding requirements. Storage systems play a critical role by mitigating peak demand periods and stabilizing supply-demand balance, ensuring continuous energy delivery during stress periods. The findings of this study demonstrate significant improvements in both cost savings and system resilience, highlighting the practical value of the proposed optimization framework in real-world power system operations. These benefits can be directly implemented in modern energy networks in the following ways:

Integration with Smart Grid Technologies: The proposed method can be deployed within existing EMS and real-time control platforms, such as SCADA systems, to optimize power dispatch and network configuration dynamically. This enables real-world grid operators to enhance decision-making efficiency while responding to uncertain grid conditions.Scalability for Different Grid Infrastructures: The flexibility of the framework allows it to be applied across different scales, including large-scale transmission networks, distribution grids, and microgrids. For instance, microgrid controllers can leverage the proposed reinforcement learning-based approach to autonomously adjust energy storage and renewable energy dispatch, reducing reliance on traditional fossil fuel-based backup systems.

Cost-Effective Investment Planning: The demonstrated cost reductions suggest that utilities and policymakers can use the framework to prioritize infrastructure investments. By identifying optimal grid reinforcement and expansion strategies under uncertainty, stakeholders can allocate resources more efficiently, reducing capital expenditures while ensuring long-term grid reliability.Enhancing Resilience Against Disruptions: The ability of the framework to handle cyber-physical threats, extreme weather events, and renewable variability suggests that real-world energy planners can integrate this model into resilience planning initiatives. Governments and grid operators can leverage the methodology to simulate and mitigate risks proactively, reducing outage probabilities and recovery times.Overcoming Implementation Barriers: While reinforcement learning-based approaches offer adaptability, real-world adoption requires addressing computational efficiency and regulatory compliance. Deploying the framework using cloud-based platforms and edge computing can enhance scalability, while working with policymakers to align AI-driven grid management with regulatory standards ensures smooth adoption.

Overall, the results suggest that the proposed model bridges the gap between theoretical optimization and practical deployment, providing a scalable, efficient, and resilient approach for modern energy systems. Future work will focus on pilot implementations in real-world testbeds, assessing further refinements needed for industrial-scale deployment. This study develops a DQN-based optimization framework to enhance power system resilience, flexibility, and economic efficiency under extreme weather conditions. One of the key theoretical innovations of this work is the incorporation of extreme weather impacts into power system modeling. Unlike traditional models that assume static operational conditions, this study introduces a probabilistic framework to assess how extreme weather events–such as storms, heatwaves, and cold snaps–affect thermal power plants, renewable energy generation, and system loads. The proposed approach models unplanned outages and derating effects for thermal power plants, while renewable energy generation fluctuations are accounted for using historical variability distributions and uncertainty-aware forecasting techniques. Additionally, temperature-sensitive load models ensure that variations in system demand due to extreme conditions are captured dynamically.Another contribution of this study is the segmented approximation of the optimization model. By using a piecewise linearization technique, the framework efficiently approximates complex non-linear relationships in power dispatch, system flexibility, and weather-dependent constraints. This decomposition allows for computational efficiency while preserving the fundamental operational characteristics of the grid. Unlike traditional optimization approaches such as Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP), which require predefined system constraints and deterministic models, the proposed DQN-based optimization framework enables adaptive decision-making in real-time. Reinforcement learning continuously refines dispatch strategies based on real-time observations, reducing the need for exhaustive scenario enumeration and allowing the system to dynamically adjust to uncertainties.This study also extends the operational flexibility assessment framework for high-variable renewable energy systems (high-VRES). A novel flexibility metric is introduced to quantify grid adaptability under conditions of renewable generation variability, extreme weather disruptions, and uncertain demand fluctuations. This metric is integrated within the reinforcement learning framework to ensure that dispatch decisions maximize both operational flexibility and cost-efficiency. The methodology is validated through extensive comparative analysis and case studies, simulating power system operations under extreme weather conditions and evaluating performance against traditional MILP-based approaches. The results demonstrate that the proposed framework significantly improves resilience, reduces computational burden, and enhances adaptability in high-VRES scenarios, confirming its applicability for real-world power system operations. In conclusion, the proposed DQN-based framework provides a promising solution for power system operators and planners, equipping them with tools to navigate the challenges posed by climate-induced uncertainties and increasing demand for clean energy. Future work could expand this model to incorporate additional resilience metrics and further refine DQN training to address more granular climate scenarios, strengthening its utility for broader applications in sustainable and resilient power systems planning.

By integrating reinforcement learning with power system decision-making, the proposed framework enables real-time adaptive control, outperforming traditional MILP-based optimization in handling dynamic uncertainties. The results demonstrate that DQN effectively optimizes power dispatch, energy storage utilization, and network reconfiguration, leading to lower operational costs, improved resource allocation, and enhanced grid resilience.

The comparative analysis confirms that the DQN-based approach reduces computational complexity and enhances decision-making adaptability, allowing the system to respond dynamically to renewable generation fluctuations, load variations, and extreme weather disruptions. The study highlights the potential for reinforcement learning in modern energy management, providing a scalable and robust decision-making framework for future power systems.

Future work will explore expanding the reinforcement learning model to multi-agent systems, allowing for distributed and cooperative decision-making across interconnected grids. Additionally, further integration with real-time energy markets and demand-side flexibility mechanisms will be examined to enhance the practical applicability of the proposed approach.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to conflict of interest but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \(\alpha _{\text {DQN}}\) :

-

Learning rate for the DQN model

- \(\mathscr {A}_{\text {DQN}}\) :

-

Action space for the DQN optimization

- \(r_t\) :

-

Immediate reward at time t

- \(\gamma\) :

-

Discount factor for future rewards in DQN

- \(\pi (a_t | s_t)\) :

-

Action selection probability of \(\epsilon\)-greedy policy

- \(\theta\) :

-

Parameters of the neural network in DQN

- \(\mathscr {D}\) :

-

Replay buffer in DQN

- \(Q(s_t, a_t)\) :

-

Q-value for state \(s_t\) and action \(a_t\)