Abstract

Lactate anaerobic threshold has been a commonly used metric in the field of training monitoring, however its invasiveness has been overwhelming. Therefore, this study utilized sweat sensors to monitor Na+ and K+ in sweat to investigate the possibility of using sweat for anaerobic threshold monitoring. Fifty-five subjects were asked to complete an incremental load riding test. The test started at 100 W and each level of load lasted 3 min with one minute of rest in increments of 25 W/3min until exhaustion. Sweat collection was performed on the left chest throughout the ride to test sweat Na+ and K+ concentrations at each level, and fingertip blood collection was performed to measure blood lactate concentrations. For high and middle level populations, sST and sPT showed higher correlation and agreement with bLT (HL: sST vs. bLT: r = 0.559 p < 0.05,sPT vs. bLT: r = 0.667 p < 0.05;ML: sST vs. bLT: r = 0.802 ,p < 0.01, sPT vs. bLT: r = 0.723 p < 0.01), whereas for low level populations the method may not predict anaerobic threshold. The findings validates the possibility of sweat monitoring on anaerobic threshold testing, which suggests that sweat metrics are linked to energy metabolism metrics, which could help to advance sweat monitoring in the field of exercise practice. Further research is needed to advance exploration in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human movement is the process of converting biological energy into mechanical energy1. At low power outputs, the body’s energy metabolism predominantly relies on aerobic energy supply. As the power output increases, the contribution of anaerobic energy supply becomes progressively more significant2,3. The transition in human energy metabolism has long been a key focus in exercise physiology research4. In 1964, Wasserman first introduced the concept of anaerobic threshold (AT)5, and in 1979, Kindermann proposed the aerobic-anaerobic transition framework6. Since then, this concept and framework have been widely used for diagnosing endurance performance and prescribing exercise regimens. With the increasing volume of scientific research related to anaerobic threshold, numerous other threshold concepts have been proposed. Among these, the submaximal process of blood lactate concentration during incremental exercise has likely become one of the most important methods for diagnosing endurance performance in sports practice7,8.

Currently, most methods for testing the anaerobic threshold are invasive, typically requiring blood sampling from areas such as the fingertip or earlobe to measure blood lactate levels. This process is costly, time-consuming, and may impose both physical and psychological stress on the subjects9. In contrast, non-invasive methods for determining the anaerobic threshold primarily rely on ventilatory threshold (VT) assessments using gas metabolic analyzers. However, the evaluation of VT is constrained by the high cost of the equipment and the expertise required by the operators10.

Sweat, as a readily accessible biomarker during exercise, has shown significant advantages in the field of training monitoring, and increasing efforts have been made to explore its potential in determining the anaerobic threshold. Tanaka et al.11 measured the concentrations of Na+, K+, and Cl− in sweat during incremental exercise, finding that as exercise intensity increased, the concentrations of electrolytes in sweat also rose, with a trend similar to that of blood lactate. With the development of microfluidic technology, the emergence of sweat sensors has liberated the process from traditional laboratory testing constraints, advancing the application of sweat in exercise monitoring. One study12 used a wearable sweat lactate sensor to visualize changes in sweat lactate during incremental exercise, discovering that as exercise intensity increased, sweat lactate concentration also increased, aligning with the blood lactate trend. Furthermore, the sweat lactate threshold exhibited a high correlation with both blood lactate threshold (LT) and VT. Additionally, Yuki et al.13 used a sweat lactate sensor to estimate the maximal lactate steady state.

Based on this, the present study utilizes the AbsoluteSweat brush-chip smart sweat analyzer to investigate the trends of sodium and potassium ions in sweat during incremental exercise, and to explore their relationship with blood lactate levels. The study also analyzes the differences and correlations between sweat-based anaerobic threshold assessment and the gold standard of blood lactate measurement.

Result

The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to analyze the relationship between sST, sPT, and bLT in participants with different fitness levels. The detailed results are presented in Table 1. HL: sST vs. bLT: r = 0.559 (p < 0.05), sPT vs. bLT: r = 0.667( p < 0.05) both implies a moderate positive correlation, statistically significant for high-level performers. ML: sST vs. bLT: r = 0.802 (p < 0.01), sPT vs. bLT: r = 0.723 (p < 0.01) both implies strong positive correlation, highly statistically significant for mid-level performers. However, different results were observed in low-level populations. LL: sST vs. bLT: r = 0.524 (p < 0.05) implies a moderate positive correlation, statistically significant for low level performers. sPT vs. bLT: r = 0.47 (p = 0.123) implies low positive correlation, but this was not statistically significant for low-level performers.

Consistency analysis was performed using Bland-Altman plots, as shown in Fig. 1. For the high-level fitness group, the mean difference between bLT and sST was 20.67 W, and the mean difference between bLT and sPT was 9.09 W. The differences for all samples fell within the consistency range, demonstrating good agreement. For the medium-level fitness group, the mean difference between bLT and sST was 15.47 W, and the mean difference between bLT and sPT was 8.33 W. Although one sample showed a large difference between bLT and sST, 95% of the samples still fell within the consistency range, indicating good agreement. For the low-level fitness group, the mean difference between bLT and sST was − 3.125 W, and the mean difference between bLT and sPT was − 8.33 W. One sample showed a large difference between bLT and both sST and sPT, with fewer than 95% of the samples falling within the consistency range, suggesting that sST and sPT are not suitable for anaerobic threshold testing in low-level fitness individuals.

Discussion

Sweat threshold, compared to lactate threshold, offers advantages in terms of ease of operation, real-time monitoring, and non-invasiveness. According to the results of this study, for the high-level and medium-level fitness groups, the sweat anaerobic threshold and blood lactate anaerobic threshold demonstrated good correlation and consistency. However, for the low-level fitness group, the sweat anaerobic threshold testing method may not be as applicable. The correlation between sodium and potassium ions in sweat and blood lactate was first observed by Tanaka et al.11. To achieve continuous sweat collection, they used a glass cylinder to cover a clean sweat collection area, then introduced 2 ml of deionized water. After one minute, the cylinder was removed, and the subsequent electrolyte concentration analysis was performed14. This study used the same exercise protocol as in the present study, and the results indicated a significant positive correlation between the electrolyte concentrations in sweat and blood lactate concentrations. The inflection points for Na+, K+, and Cl− in sweat corresponded to blood lactate concentrations of 4.04, 3.61, and 3.83 mmol/L, respectively, which corresponded to exercise intensities of 64.42% VO2max, 61.96% VO2max, and 62.14% VO2max. These findings suggest that in incremental exercise protocols, changes in electrolyte concentrations in sweat are closely related to changes in blood lactate concentrations, and the inflection points of the electrolytes occur near the OBLA (onset of blood lactate accumulation) exercise intensity.

It is well established that during muscle contraction, the concentration of K⁺ in both blood plasma and interstitial fluid increases15,16. Moreover, the amount of K+ released from active muscle fibers rises with increasing exercise intensity16, a phenomenon attributed to complex mechanisms including action potential–mediated efflux17, voltage-dependent K+ channels18, osmotic concentration shifts19, and adrenergic‐driven transport16. In addition, the total quantity of K+ released by active muscle has been shown to exceed the net increase in extracellular K+, because a portion of the K⁺ entering the interstitium is rapidly reabsorbed into muscle cells via the Na⁺–K⁺ ATPase pump20. Activation of the Na⁺–K⁺ pump is modulated by both changes in extracellular K⁺ concentration and adrenergic stimulation18, and may be further enhanced by exercise‐induced hyperthermia. However, elevated intracellular inorganic phosphate levels inhibit Na+–K+ ATPase activity, suggesting that plasma K⁺ concentration during exercise may reflect intracellular energy fluxes16 Because muscle K+ uptake and the resulting shifts in extracellular concentration occur on a very rapid timescale, conventional sampling methods—which require several minutes—may fail to capture these transient changes. In contrast, the sweat sensor employed in the present study provides measurements at one‐minute intervals, a high‐frequency sampling rate that may account for the differences observed when compared with earlier work11. Furthermore, athletic training status has been shown to influence Na⁺/K⁺ ATPase activity: well‐trained individuals exhibit greater pump activity, thereby enhancing K+ reuptake21,22,23. This training‐related modulation of ion transport may help explain why the sweat‐based threshold detection method is less applicable to low‐fitness participants.

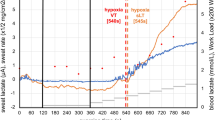

Several studies have reported a correlation between sweat Na⁺ concentration and sweat rate24,25. Of particular interest is one investigation into how a sweat ion concentration index varies with sweat rate under passive heat stress26. In that study, eight participants underwent 50 min of passive heating by immersing their lower limbs in a 42 °C water bath. Sweat ion concentration was estimated by measuring the conductivity of perfusate mixed with sweat, sweat rate was determined via the ventilated capsule method27, and core temperature was monitored sublingually. Results showed that both the sweat ion concentration index and sweat rate began to increase almost simultaneously, exhibiting two distinct linear relationships. In the low sweat-rate phase (sweat rate < 0.30 ± 0.08 mg cm–2 min–1), the relationship was relatively gradual, with a slope of 0.02 ± 0.01 V per (mg cm–2 min–1). In the moderate sweat-rate phase (sweat rate ≥ 0.30 ± 0.08 mg cm–2 min–1), the relationship became markedly steeper, with a slope of 0.30 ± 0.08 V per (mg cm–2 min–1), a statistically significant change from the low-phase slope (P < 0.05). The core temperature thresholds at which the ion concentration index and sweat rate began their sharp increases were 37.78 ± 0.08 °C and 37.71 ± 0.08 °C, respectively—indicating that around 37.7 °C core temperature, both measures rise concurrently. The authors explained these findings by noting that at low sweat rates, the sweat gland ducts have sufficient ion-reabsorption capacity to buffer changes in sweat electrolyte concentration. Once a critical sweat-rate threshold is exceeded, reabsorption capacity becomes saturated, leading to a rapid rise in sweat ion concentration. This mechanism is supported by Slegers et al., who found that while increasing sweat secretion is accompanied by increased Na⁺ reabsorption, the reabsorption rate reaches an upper limit28. Although the study did not employ exercise-induced sweating, it provides evidence for an inflection point in sweat ion concentration dynamics that is closely linked to both sweat rate and core temperature. Given that exercise similarly elevates core temperature and sweat rate—and that these effects become more pronounced with higher exercise intensities—these passive-heat findings likely translate to exercise settings as well.

Conclusion

In this study, wearable sweat sensors were employed to successfully predict the anaerobic threshold in medium- and high-level fitness groups, demonstrating strong correlation and agreement with the lactate-based anaerobic threshold. These findings indicate that sweat monitoring holds considerable promise for physiological performance assessment. With further technological advancements, more comprehensive and diversified sweat-based testing protocols may be developed in the future.

Methods

Participants

Fifty-five male university students with varying levels of physical fitness were invited to participate in this study. The basic information of the participants is presented in Table 2. Body fat percentage was measured using the American GE Lunar iDEXA dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Hologic QDT-4500, Hologic, USA), with testing conducted in the morning after an overnight fast. All participants were provided informed consent during the study. All participants were healthy, with no history of cardiopulmonary disease, and had no major injuries or illnesses within the month preceding the test. Additionally, participants were prohibited from consuming alcohol during the week prior to testing. Based on the participants’ fitness levels, we divided them into high-level(HL), medium-level(ML), and low-level(LL) groups. The high-level group had undergone more than three years of endurance training, the medium-level group had undergone more than one year of endurance training, and the low-level group had undergone no more than three months of training. As shown in Table 2, the maximum load values for the three groups indicate significant differences in physical fitness among the groups.

Procedures

All participants were required to complete an incremental load cycling test on a power cycle, with venous blood samples collected three times: before, during, and after the test. During the exercise, the concentrations of Na+ and K+ in sweat were measured. Blood lactate, heart rate, and Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) were recorded at each load stage to determine when the participants reached exhaustion. Participants were instructed to select a comfortable pedaling cadence between 70 and 95 rpm and to maintain a stable cadence throughout the entire test.The research methods used in this experiment have been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Sport University, and all methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

-

(1)

Incremental load cycling test.

The incremental load testing protocol is illustrated in Fig. 2. Participants first warm up for 10 min at 50 W, during which an appropriate pedaling cadence is determined. Afterward, they perform a 5-minute stretching session, following which the formal experiment begins. The starting power is set at 100 W, with each load stage lasting 3 min, followed by a 1-minute rest. The intensity is increased by 25 W every 3 min until the participant reaches exhaustion. Exhaustion is defined as the point at which the participant is unable to maintain the determined cadence for 10 s or subjectively no longer wishes to continue cycling.

-

(2)

Lactate threshold assessment.

Blood lactate was collected using the EKF Lactate Scout4 portable lactate tester. The test strip is first inserted into the lactate meter according to the indicated direction, with the droplet shape displayed to signal that measurement is possible. A blood sample is then collected from the fingertip using a lancet, with the first drop of blood wiped away. The second drop is placed onto the test strip for measurement, and the blood lactate value is recorded. Blood lactate samples are collected at the end of each load stage.

The blood lactate threshold (bLT) is defined as the point at which blood lactate levels first rise significantly. Two experienced researchers visually assess the data to identify the first point of increase from baseline levels. If there is any disagreement between the two researchers in determining the lactate threshold, a third researcher independently reviews the data. The final lactate threshold is determined through consensus among all three researchers.

-

(3)

Sweat threshold assessment.

Sweat collection was performed using the AbsoluteSweat brush-chip smart sweat analyzer (Shenzhen Refresh Biosensing Technology Co., Ltd.). The left chest of the participant was selected as the site for the sweat sensor placement. Prior to testing, the left chest area was cleaned with alcohol and hair was removed. The sweat patch was then connected to the sweat sensor, and once the software displayed a successful connection, the sensor was applied to the participant’s left chest. Afterward, the participant completed the warm-up, and once the application software displayed successful sweat detection and showed values for Na+, K+, and sweat rate, the formal testing began. The procedure is outlined in Fig. 3.

The sensor provides one data point per minute. At the end of each load stage, the immediate concentrations of Na+ and K+ in sweat are recorded. The sweat sodium threshold (sST) and sweat potassium threshold (sPT) are defined as the points at which the first significant upward deviation of sodium and potassium ions in sweat occurs relative to baseline levels, obtained using graphical methods. The sST and sPT points are confirmed through consensus among three researchers.

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS 22.0 and GraphPad Prism 9 software. All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check for normality of the data. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to examine the relationship between sST, sPT, and bLT. If the data did not conform to a normal distribution, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used instead. The strength of the correlation was classified into four levels: very weak (r ≤ 0.3), weak (r = 0.3–0.5), moderate (r = 0.5–0.7), and strong (r > 0.7). The consistency between different anaerobic threshold detection methods was further validated using Bland-Altman plots.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Li, Y. M., Ji, X. N. & Zi, W. Nature of human science. China Sport Sci. 34 (02), 11–17 (2014).

Li, Y. M. & Mao, C. Energy contribution in competitive sports-error in need of correction. China Sport Sci. 34 (10), 93–97 (2014).

Gastin, P. B. Energy system interaction and relative contribution during maximal exercise. Sports Med. 31 (10), 725–741 (2001).

Poole, D. C. et al. The anaerobic threshold: 50 + years of controversy. J. Physiol. 599 (3), 737–767 (2021).

Wasserman, K. & Mcilroy, M. B. Detecting the threshold of anaerobic metabolism in cardiac patients during exercise. Am. J. Cardiol. 14, 844–852 (1964).

Kindermann, W., Simon, G. & Keul, J. The significance of the aerobic-anaerobic transition for the determination of work load intensities during endurance training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 42 (1), 25–34 (1979).

Faria, E. W., Parker, D. L. & Faria, I. E. The science of cycling: physiology and training - part 1. Sports Med. 35 (4), 285–312 (2005).

Atkinson, G. et al. Science and cycling: current knowledge and future directions for research. J. Sports Sci. 21 (9), 767–787 (2003).

Nikooie, R. et al. Noninvasive determination of anaerobic threshold by monitoring the %SpO2 changes and respiratory gas exchange. J. Strength. Cond Res. 23 (7), 2107–2113 (2009).

Belardinelli, R. et al. 10-year exercise training in chronic heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 60 (16), 1521–1528 (2012).

Tanaka, H. et al. Changes in the concentrations of Na+, K + and Cl- in secretion from the skin during progressive increase in exercise intensity. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 64 (6), 557–561 (1992).

Seki, Y. et al. A novel device for detecting anaerobic threshold using sweat lactate during exercise. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 4929 (2021).

Muramoto, Y. et al. Estimation of maximal lactate steady state using the sweat lactate sensor. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 10366 (2023).

Tanaka, H. et al. Dependence on exercise intensity of changes in electrolyte secretion from the skin sampled by a simple method. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 60 (6), 407–411 (1990).

Buono, M. J. & Sjoholm, N. T. Effect of physical training on peripheral sweat production. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 65 (2), 811–814 (1988).

Busse, M. W. & Maassen, N. Effect of consecutive exercise bouts on plasma potassium concentration during exercise and recovery. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 21 (5), 489–493 (1989).

Sjøgaard, G., Adams, R. P. & Saltin, B. Water and ion shifts in skeletal muscle of humans with intense dynamic knee extension. Am. J. Physiol. 248 (2 Pt 2), R190–R196 (1985).

Juel, C. et al. Lactate and potassium fluxes from human skeletal muscle during and after intense, dynamic, knee extensor exercise. Acta Physiol. Scand. 140 (2), 147–159 (1990).

Wilkerson, J. E. et al. Plasma electrolyte content and concentration during treadmill exercise in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. Respir Environ. Exerc. Physiol. 53 (6), 1529–1539 (1982).

Clausen, T., Everts, M. E. & Kjeldsen, K. Quantification of the maximum capacity for active sodium-potassium transport in rat skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 388, 163–181 (1987).

Nielsen, J. J. et al. Effects of high-intensity intermittent training on potassium kinetics and performance in human skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 554 (Pt 3), 857–870 (2004).

Murphy, K. T. et al. Effects of endurance training status and sex differences on Na+,K+-pump mRNA expression, content and maximal activity in human skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol. (Oxf). 189 (3), 259–269 (2007).

Clausen, T. Effects of age and exercise training on Na+-K + pumps in skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 285 (4), R720–R721 (2003).

Nose, H. et al. Shift in body fluid compartments after dehydration in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 65 (1), 318–324 (1988).

Verde, T. et al. Sweat composition in exercise and in heat. J. Appl. Physiol. Respir Environ. Exerc. Physiol. 53 (6), 1540–1545 (1982).

Shamsuddin, A. K. et al. Changes in the index of sweat ion concentration with increasing sweat during passive heat stress in humans. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 94 (3), 292–297 (2005).

Kondo, N. et al. Function of human eccrine sweat glands during dynamic exercise and passive heat stress. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 90 (5), 1877–1881 (2001).

Slegers, J. F. A mathematical approach to the two-step reabsorption hypothesis. Bibl. Paediatr. 86, 74–88 (1967).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The research idea was proposed by Z L, and the pre-feasibility analysis was completed by Z L, M C, L Y and J W. The experimental design and execution were done by Z L , L Y, J W and M C. Data analysis was done by M C. The thesis was written by Z Land M C. The review of the paper was done by L Y and J W.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, Z., Cao, M., Yan, L. et al. Feasibility study of a novel wearable sweat sensor for anaerobic threshold determination. Sci Rep 15, 30467 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16559-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16559-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Potential Mechanisms of Exercise-Mediated Ferroptosis Regulation in Central Nervous System Diseases

Molecular Neurobiology (2026)