Abstract

The International Normalized Ratio (INR) is a laboratory test used to monitor and adjust medication with vitamin K antagonists. The alert values of the INR obtained in the laboratory must be managed efficiently to provide the best management for the patient. The aim of the study was to evaluate the risk levels associated with INR alert values for the laboratory in a tertiary care hospital and compare the findings with the established benchmarks. The study was conducted from September 2023 to August 2024 at the Clinical Laboratory from Emergency County Clinical Hospital of Targu Mures. Both risk levels associated with the occurrence of alert values for INR > 4.5 and underlying causes of these values were assessed. Plasma samples collected in all wards were analyzed using Sysmex CS-2500 instrument. The sample’s journey through the laboratory was analyzed. The risk was assessed and a daily probability of alert value occurrence for INR was calculated. A total number of 42,799 plasma samples were analyzed, out of which 347 (0.81%) had INR alert values and were collected from 246 patients, some having more than one sample collected. This study showed that INR alert values > 4.5 represent an Unacceptable risk level, with an expected daily occurrence of λ = 0.95 (61% probability of ≥ 1 event per day). The consequence is critical in the risk assessment matrix that corresponds to a frequent probability. The laboratory considered the risk of INR values > 4.5 to be unacceptable both as frequency and consequences. Incomplete documentations of phone communications and resampling delays (> 6 h in 30% of the samples) were identified as potential failure modes. Therefore, laboratories are expected to implement strict control measures to effectively mitigate this risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The International Normalized Ratio (INR) is a standardized laboratory test used to monitor anticoagulant therapy with vitamin K antagonists (eg. Warfarin) and to guide dosage adjustment1. The INR values also recognized as independent predictors of mortality in cancer patients2.

Alert (also called critical values) indicate potentially life-threatening conditions and require prompt corrective action to ensure patient safety3. The selection of alert values varies between laboratories, depending on guidelines, agreements with the clinicians and patient population patients. Although studies focusing on the occurrence of INR alert values are limited, a tertiary hospital study reported a frequency of 0.61%4.

Risk management in the clinical laboratory is an essential component of quality management system and is mandated by ISO 15189:2022 Standard5 which emphasizes a continuous cycle of risk identification, quantification, mitigation and monitoring5. The acceptability of a given risk depends on both its probability of occurrence and the severity of its consequences6. These consequences may refer to the patient, clinician or the laboratory itself as an organization.

The aim of the study was to assess the risk associated with INR alert values for in a tertiary care hospital laboratory by applying a quantitative probability model within the ISO 15189:2022 framework. Operational metrics including the timing of second sample collection and documentation of phone communications, were also evaluated to provide benchmarks for future risk mitigations.

Material and methods

A retrospective study was conducted from September 2023 to August 2024, at the Clinical Laboratory from Emergency County Clinical Hospital of Târgu Mureș (a tertiary care hospital) with ED (Emergency Department) and ICU (Intensive Care Unit) wards. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee (no. 2045/23.02.2024) of the Emergency County Clinical Hospital of Targu Mures and informed consent was waived because of the retrospective design of the study.

Population

Plasma samples collected in all wards were analyzed using Sysmex CS-2500 instrument. Data were extracted from the laboratory information system (LIS). Demographic data (age, sex), the requesting ward (ED, ICU, or other) and the patient’s primary diagnosis, were recorded from the Laboratory Information System (LIS).

Risk assessment

To quantify the daily probability of INR alert values, we applied a Poisson probability model. The expected daily number of alert values (λ) was calculated as: λ = ndaily*p, where ndaily = Total samples/Days and represents the mean daily number of samples and p = Alert samples/ Total Samples and is the probability of an alert sample. The probability of having at least one INR alert value per day was calculated as: P (≥ 1) = 1 − ℯ(−λ).

Severity and probability categories were defined in accordance with ISO 15189:2022 risk management principles and adapted from laboratory risk assessment literature5,6,7,8. These are presented in Table 1.

Operational matrix

For patients with repeated INR testing, the time interval between the receipt of the first sample and the collection of a second sample was recorded. Cases in which alert values were communicated by phone were also recorded, when explicitly recorded in laboratory records.

Risk assessment was performed using 5 × 5 matrix, assigning risk level based on the calculated probability and the defined severity of clinical consequences. The data were analyzed in Microsoft Office Excel 2016.

Results

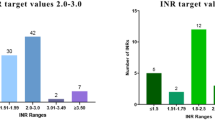

A total of 42,799 plasma samples were analyzed out of which 347 (0.81%) had INR alert values and originating from 246 unique patients. Out of the these, 231 results were between 4.5–7 and 116 results were > 7.

The average number of samples analyzed per day was 117.3. The expected daily number of INR alert values was λ = 0.95, corresponding to a 61% probability of observing at least one such value per day. In the risk matrix, this corresponds to a Frequent probability with a Critical consequence, resulting in an Unacceptable risk level. The risk matrix is shown in Table 2.

Most alert values, (292/347;84%) were obtained from patients older than 60 years; only 7 (2%) in patients under 18. The majority (199/347;57%) were from the Emergency Department with 25 (7.2%) from ICU patients.

For the 42 patients that had a second sample collected, the mean time to repeat sampling was 5.3 h (median 4.2 h; range 0.8–16.5 h). Most samples (23/42) were collected in 2–6 h from the initial collection; 6/42 in less than two hours but 13/42 samples were collected after more than six hours. Although all alert values were flagged in the LIS ensuring no critical results were missed, only 7 cases were explicitly documented as communicated by phone. The true number was likely higher due to incomplete manual recording.

In 30/ 246 (12%) the main cause for ED presentation was bleeding (type of bleeding is shown in Table 2) and six patients presented themselves for INR above 7 at screening tests performed in outpatient units but without bleeding.

The main underlying causes for these values are shown in Table 3.

Out of these, 23 patients received treatment with fresh frozen plasma, 19 received vitamin K and 9 received both.

Discussions

This study assessed the risk associated with INR alert values in a tertiary hospital laboratory using the ISO15189:2022 risk management framework. The analysis demonstrated that INR > 4.5 represent an Unacceptable risk level due to their frequent occurrence and their association with bleedings requiring medical intervention. The consequence for the patient was classified as Critical in accordance with ISO15189:2022 definitions. Although such events occur routinely in the laboratory, their frequency does not minimize their clinical severity. Compared with previously published studies of 0.61% in a tertiary hospital4, our study found a slightly higher proportion (0.81%) of INR alert values. The difference may be partially explained by lower threshold of 4.5 used in our study. This threshold was established in accordance with the clinicians from our ED. In the literature the value of 5.0 is considered as an evidence-based alert value but laboratories should consider this value as a starter list and tailor the list of alert values according to their needs3.

The consequences for the patient may not be similar in all hospitals or laboratories. In the population of our study, all patients needed medical attention since the majority of INR alert values were obtained in patients from ED (57%) and 30 patients (12%) had bleedings as the main presentation cause. In the University Hospital Aga Khan, 25 out of the 240 patients (10.6%) included in the study had bleeding at presentation4.

One of the consequences, beyond medical care needed that in some cases, is sample recollection. The re-collection of samples may have different reasons: for some patients the reason behind this is confirmation of the initial value and for others a re-check after a medical intervention. In our sample population, 17% of the patients had a sample re-collected and most of them (23/42) in less than six hours from the initial sample.

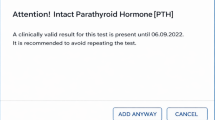

The rationale for this study was to evaluate not only the probability occurrence but also to enable the laboratory to better allocate resources to manage these values. The occurrence of alert INR values triggers a series of events in the laboratory that need clear guidelines and SOP’s similar for all alert values3. In some studies1,3,9 the time spent by the laboratory staff to communicate such values was evaluated and the use of automated alerts systems and direct communication was compared10,11. In our hospital, all alert values were documented in the LIS but only seven were documented as direct communication. The different factors (like the occurrence of alert values during working hours and outside working hours) that may influence communication time was also assessed12,13,14. Since this study was conducted in an Emergency Laboratory, such differences are not expected but the low number of documented communications is likely due to staff diligence on documenting their actions.

Although differences in practice impacts the way clinicians respond to alerts, the use of AI to support these actions was also assessed 14,15, and it has been found that at least for alert values in duplicate measures the computer algorithm support could have averted more than 1900 alerts.

By integrating a quantitative probability model with ISO-based risk classification and operational benchmark, the study provides a methodology that other laboratories may use and adapt for the risk management cycle of risk identification, quantification, mitigation and monitoring.

Conclusions

This study showed that INR alert values > 4.5 represent an Unacceptable risk level, with an expected daily occurrence of λ = 0.95 (61% probability of ≥ 1 event per day). Although frequent, these values retain clinical severity as they often require medical intervention. Incomplete documentations of phone communications and resampling delays (> 6 h in 30% of the samples) were identified as potential failure modes. To mitigate the risk laboratories should adopt automated alert systems and prospective monitoring of time-to-communication to complete the risk management cycle.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed in the presented study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Arbiol-Roca, A. et al. Analysis of laboratory critical values at a referral Spanish tertiary university hospital. Biochem. Med. 29, 010704 (2019).

Liang, J.-D. et al. Association between PT, PT-INR, and in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with tumors: A retrospective cohort study. Front. Public Health 11, 1036463 (2023).

Truijens, K., Frans, G. & Vermeersch, P. Critical results in laboratory medicine. Clin. Chem. 70, 1220–1230 (2024).

Hussain, S., Moiz, B. & Afaq, B. Quality indicators for critical international normalized ratio measurements in a hemostatic laboratory. Clin. Biochem. 48, 483–488 (2015).

ISO. 15189: Medical Laboratories: Particular Requirements for Quality and Competence. International Organisation for Standardisation (2022).

Jayamani, J., Janardan, C. C., Appan, S. V., Kathamuthu, K. & Ahmed, M. E. A practical tool for risk management in clinical laboratories. Cureus 14, e32774 (2022).

CLSI. Laboratory Quality Control Based on Risk Management: Approved Guideline. CLSI Document EP23-A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2011).

ISO. 31000:2018 Risk Management—Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization (2018).

Howanitz, P. J., Steindel, S. J. & Heard, N. V. Laboratory critical values policies and procedures: A College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study in 623 institutions. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 126, 663–669 (2002).

Etchells, E. et al. Real-time clinical alerting: Effect of an automated paging system on response time to critical laboratory values—a randomised controlled trial. Qual. Saf. Health Care 19, 99–102 (2010).

Etchells, E. et al. Real-time automated paging and decision support for critical laboratory abnormalities. BMJ Qual. Saf. 20, 924–930 (2011).

Korn, D., McMurtry, M. S., George-Phillips, K. & Bungard, T. J. Critical international normalized ratio results after hours: To call or not to call?. Can. Fam. Physician 63, e170–e176 (2017).

Agarwal, R., Chhillar, N. & Tripathi, C. B. Study of variables affecting critical value notification in a laboratory catering to tertiary care hospital. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 30, 89–93 (2015).

Baron, J. M., Huang, R., McEvoy, D. & Dighe, A. S. Use of machine learning to predict clinical decision support compliance, reduce alert burden, and evaluate duplicate laboratory test ordering alerts. JAMIA Open 4, ooab006 (2021).

Hylek, E. M., Chang, Y. C., Skates, S. J., Hughes, R. A. & Singer, D. E. Prospective study of the outcomes of ambulatory patients with excessive warfarin anticoagulation. Arch. Intern. Med. 160, 1612–1617 (2000).

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support were received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Oana Roxana Oprea, Ana-Maria Fotache, Corina-Maria Rus, Minodora Dobreanu; Methodology: Oana Roxana Oprea; Formal analysis: Oana Roxana Oprea, Minodora Dobreanu; Investigation: Ana-Maria Fotache, Corina-Maria Rus; Data curation: Ana-Maria Fotache, Corina-Maria Rus; Project administration: Oana Roxana Oprea; Writing—original draft preparation: Oana Roxana Oprea; Writing—review and editing: Oana Roxana Oprea, Ana-Maria Fotache, Corina-Maria Rus, Minodora Dobreanu; Funding acquisition: /Resources: Oana Roxana Oprea, Minodora Dobreanu; Supervision: Minodora Dobreanu; Validation: Oana Roxana Oprea, Ana-Maria Fotache, Corina-Maria Rus, Minodora Dobreanu; Visualisation: Minodora Dobreanu; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Emergengy Clinical County Hospital Targu Mures no. 2045/23.02.2024.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oprea, O.R., Fotache, AM., Rus, CM. et al. Laboratory risk management for INR alert values. Sci Rep 15, 31800 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16944-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16944-z