Abstract

Glass fiber-reinforced engineered cementitious composite (GFRECC) is being used in this study to repair short square reinforced concrete columns that are structurally weak and measure 100 mm \(\times\) 100 mm \(\times\) 1000 mm. Polypropylene fibers and E-glass rovings are combined in a cementitious matrix to create the composite. Eight columns were cast and tested: two low-strength concrete columns (E-A4), two standard control columns (E-A1), two with inadequate main reinforcement (E-A2), and two with insufficient lateral ties (E-A3). The GFRECC technology was used to repair and retrofit all specimens after they had been preloaded axially until the first obvious cracks appeared. With ANSYS 14.0, corresponding numerical models (N-A1, N-A2S, N-A3S, and N-A4S) were created and examined. To evaluate the restoration of ultimate load capacity, stiffness, energy absorption, and ductility, a parametric study was carried out. Retrofitting has enhanced the ultimate load for E-A2S and E-A3S columns. The increment was noticed as 2.36 and 2.52 times the value for the E-A1 column. A similar improvement of 2.33 and 2.48 times was noticed for N-A2S and N-A3S columns. Compared to E-A1, percentage increase in stiffness modulus for E-A2S, E-A3S, and E-A4S were 114.06%, 89.75%, and 14.19% respectively. Corresponding increment for N-A2S, N-A3S, and N-A4S were 120.5%, 100.1%, and 19.95% respectively. In the case of toughness modulus similar behavior was noticed from experimental and numerical results. Enhancement in energy ductility was 77.36%, 42.95%, and 15.7% for E-A2S, E-A3S, and E-A4S columns, compared to the control column. Corresponding increment for N-A2S, N-A3S, and N-A4S were 64.12%, 44.16%, and 23.14% respectively. Effective grouting in conjunction with extra wrapping layers improved the structural behavior of low-grade concrete columns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reinforced concrete (RC) structures need upgradation of operation in the service life. Since many structures built in the past were not satisfying the present code requirements and accidental loads, it became necessary to strengthen these structures. Many techniques implemented in the past unnecessarily increased the self-weight of the structure and also led to un-preferable corrosion of strengthened members. Usage of FRP is the latest technique which utilizes organic epoxy as a binder. Wide range of FRP composites like glass, carbon, and aramid fibers along with polyester, epoxy, or vinyl-ester matrices were used for retrofitting structural components in earlier research works1,2,3,4,5,6.

The wrapping up rectangular short RC columns using CFRP sheets enhanced both the load-carrying ability and ductility7. The experimented with the performance of GFRP-wrapped rectangular RC columns subjected to compression and found that both compressive strength and deflection ductility were improved considerably8. The performance of FRP retrofitted RC column. The different data included in the study are the grade of the concrete and the shape of the column9 .The study reported that the behaviour was enhanced for circular-shaped columns, compared to rectangular columns. Eid et al.10 concentrated on wrapping circular columns through FRP composites as the comparison shows in Table 1. The study was adopted for both normal and high-strength concrete and recommended increased layers for achieving improved compressive strength. It was inferred that ductile behaviour was reported in normal-grade concrete columns. It was reported that the cover concrete was intact without any spalling and debonding of composites. The response of RC columns under eccentric load. The study reported that wrapping was effective even after the concrete reached the ultimate value11. The presence of fiber composites was found to increase the compressive stress and strain in the column. The experimented with the eccentric loading of strengthened columns12. Strengthening was carried out using fiber-reinforced cementitious matrix. It was confirmed that confinement using longitudinal Fiber Reinforced Cementitious Mortar (FRCM) improved the ductility of eccentrically loaded columns. Previous studies have highlighted the advantages of using inorganic binders in fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) composites for enhanced performance13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. The axial performance of FRP-ECC-confined RC columns has not been extensively studied in the past, despite the great potential of these systems. An ECC-carbon fiber sheet composite composed of low calcium fly ash has been discussed23,24 to function well mechanically under saltwater conditions. Similarly, research25,26 has shown that, at comparable confinement ratios, FRP-confined ECC columns are more ductile than traditional RC columns confined with FRP. To ensure the safe and efficient use of FRP-confined ECC columns in structural engineering, more research is necessary to fully comprehend the impact of size on the compressive behavior of these columns.Wang et al.27 concentrated on maximizing the use of concrete by adding gangue aggregate. Their theoretical investigation sought to enhance aggregate concrete performance by thoroughly examining the mechanisms of interaction in hybrid fiber-reinforced polymers. The purpose of this work was to improve the ductility of FRP-confined high-strength concrete (HSC) columns by introducing an engineered cementitious composite (ECC) between the fiber sheet and the concrete. According to the results, the hybrid composite columns (fiber sheet-ECC-HSC) exhibit better confining efficacy and a more even circumferential strain distribution than traditional FRP-confined HSC columns. This leads to enhanced ductile compressive performance, which is ascribed to a higher ultimate axial strain28. Numerical analysis were conducted a of both axial and eccentric loading of concrete columns and reported that retrofit have enhanced the ultimate strength for both types of loading29. Shams AL-Amin and Raquib Ahsan30 carried out the analysis numerically for the RC column for lateral loading. It was reported that the failure of the columns was due to crack formation from the base of the column followed by body cracks. In the past, the efficiency of using ANSYS for carrying out finite element based non - linear analysis of RC beams was proved by many researchers31,32,33. The earlier research involved investigating the efficiency of ANSYS for the analysis of RC beams and the benefit of performing numerical simulation. Different stages of the response of the finite element model of RC beam were examined from initial crack to failure. Numerical analysis of fire-damaged RC columns was carried out by Bhuvaneshwari et al34. It was inferred that the ductility behaviour of strengthened columns gets enhanced due to GFRC wrapping. Experimental and numerical analysis of GFPPECC strengthened fire-damaged beam members were performed22. It was proved that confinement through GFPPECC was effective in strengthening fire-damaged reinforced concrete beam members. A review of the usage of FRC for strengthening RC structures was concentrated35. The efficiency under extreme condition and future scope has been discussed in detail. The effectiveness of different fiber composite systems in columns under seismic excitation was concentrated36. The suitability of each fiber system was discussed in detail for practical applications. The confinement effect of recycled aggregate concrete columns using CFRP wraps was experimented37. The optimum replacement percentage of recycled aggregate was reported as 30%. They also recommended that for similar concrete, design equations available in ACI 318-19 and ACI 440.2R-17 codes38 could be effectively applied. Numerical investigation of pre-damaged RC columns strengthened using FRP was studied39. The hardening/softening rule in the Concrete Damaged Plasticity Model was changed to introduce the preload effect on FRP confinement and found to give satisfactory results.

Research significance

From the earlier research, it was understood that strengthening structural components using FRC composites would be effective. Several constructions carried out in the past failed to meet the present code revisions. The present study will concentrate on introducing an efficient retrofitting technique to retrofit the structurally deficient reinforced concrete columns using the GFRECC technique. The confinement effect of GFRP is strengthened by the strain-hardening and crack-bridging qualities of the ECC, which results in a better load-bearing capacity than TRM systems that are more brittle and prone to debonding. Compared to epoxy-based GFRP or TRM systems, inorganic adhesives combined with ECC offer superior long-term durability by improving substrate compatibility and withstanding high temperatures and harsh conditions.

Experimental analysis

Materials used

The study used OPC 53 grade cement with a specific gravity of 3.13, conforming to IS 12269:201340. Aggregates conforming to IS 383:197041 were used for the concrete mix. Natural sand passing through a 4.75 mm sieve, with a specific gravity of 2.54 and a fineness modulus of 3.27, was used as fine aggregate. Graded coarse aggregate ranging from 4.75 to 12.5 mm in size was used, with a specific gravity of 2.68 and a fineness modulus of 2.92. Table 2 shows the mix proportion for M30 grade concrete (1:0.98:2.43) as per IS 10262:200942, which was used for casting columns A1, A2, and A3. Column A4 was cast using M15 grade concrete (1:2.53:5.3), and the mix proportions are provided in Table 3. Wrapping was carried out using a bidirectional woven roving glass fiber sheet, and its properties (as provided by the supplier) are shown in Table 4. Concrete cubes (150 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm) and cylinder specimens (150 mm × 300 mm) were tested to determine compressive strength. The ultimate strengths obtained were 39.06MPa for M30 and 22MPa for M15 concrete, with split tensile strengths of 3.90MPa and 2.8MPa, respectively. Table 5 presents the mix proportion of ECC.

Direct tension tests on high-yield strength deformed bars (12 mm diameter) and mild steel bars (8 mm diameter) resulted in yield strengths of 422 MPa and 252 MPa, respectively.

Casting and preloading of specimens

A total of eight reinforced concrete square columns were cast. Two columns (E-A1) were used as control columns. According to IS 456-2000, the control column (100 mm x 100 mm x 1000 mm) reinforced with main rebars of 4 # 12mm and lateral ties of 8mm at 200 mm c / c was cast. The column specimens were cast with enlarged areas at the ends. The setup was followed to achieve uniform load distribution as discussed8. Test ends of columns were provided with corbel (100 mm x 100 mm x 300 mm) to have sufficient flexural and shear strengths under the applied load of the column as suggested11. The provision of head and tail increased the shear load capacity of columns under similar repeated loading was also proved.

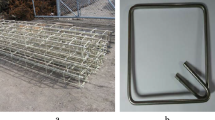

The remaining six columns were used as structurally deficient columns. E-A2 was cast as main-bar deficient columns (4 # 10 mm main bars). E-A3 was cast as lateral tie deficient columns (8 mm dia with 400 mm c/c spacing). E-A4 was cast as concrete grade deficient columns (M15 concrete). The materials and reinforcement detailing used in the study are illustrated in Fig. 1a, b and c respectively. The end conditions for all the columns were followed with one end pinned and the other being fixed. Loading was achieved in a 1000 kN capacity loading frame. The schematic view of the testing of columns and preloading of columns were shown in Fig. 2a and b respectively. LVDT was used to pick the axial and lateral deflection of the columns. Axial loading was applied to the control specimen until it finally failed. The remaining three examples, on the other hand, were preloaded axially until the first obvious cracks developed, which happened at about 30-35% of the ultimate load. The corresponding crack patterns and their locations are shown in the schematic included in the manuscript.

Repairing and retrofitting of preloaded Columns

The preloaded column is shown in Fig. 3a were repaired by using polymer concrete. Cement and tapecrete polymer in proportion 1:0.5 was used for repair works. The repaired columns were water-cured for 28 days. The repaired and cured columns were retrofitted using GFRECC composite. The mix proposition of the ECC composite43 was cement (1 kg): polypropylene fiber (18.75 g): water (0.25 l): and air entraining agent (12.5 ml). Since earlier researchers faced difficulty in achieving ductile behavior of confined components using FRC, work is required to concentrate on fiber-based cementitious binders44. The addition of fiber to the cementitious binder would enhance the ductility of the composites. For applying the composite, the surface of the repaired columns was wetted and the composite was applied over the faces of the columns. Then it was wrapped with glass fiber sheets with an overlap of 100 mm. One more layer of composite was placed and the sheet was pressed to expel air and similar procedure was followed by Tomaz Trapko12. Figure 3b and c show the wrapped column and the axial loading of the retrofitted column respectively.

Numerical analysis

Numerical modeling and meshing

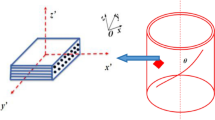

Similar columns were modeled and analysed using ANSYS 14.0. Solid65 element Fig. 4a was used for concrete and ECC binder, Link8 Fig. 4b, a spar element was used for steel reinforcements and Shell93 Fig. 4c element was used for modeling the finer rovings as followed in earlier studies29,30,31,45.

The linear and nonlinear material properties were input. The inputs for linear material properties for concrete, steel, E-Glass sheet, and ECC are displayed in Table 6. A nonlinear stress-strain plot following IS456-200046 was input for concrete Fig. 6a and b The criteria of failure for concrete as per Von Mises failure theory along with the William and Warnke (1974) model was given as input. It should be mentioned that the confinement effect and crack opening behavior are not specifically taken into consideration by the William and Warnke model. It is advised that future research employ sophisticated constitutive models that can capture nonlinear cracking and confinement mechanisms as shown in Table 7, especially in ECC-concrete systems, in order to increase simulation accuracy. The failure behavior of concrete is described by Eqs. (1)–(4).

To get the crack and crush plot in concrete, the shear transfer coefficients have been given as input. The range is from 0 to 1 where 0 mentions a smooth crack and loss of shear transfer and 1 mentions a rough crack without shear transfer. The values given as input for convergence Table 8 are as per the study47. The cracking stress under uniaxial tension as per IS 456-2000 is calculated using Eq. (4). The calculation error percentages between ANSYS and experimental results depict in Table 8 for ultimate load, stiffness modulus, toughness modulus, and energy ductility.

The real constant for the Link8 element was the cross-sectional area and for the Shell93 element was the shell thickness. A total of four columns (100 mm x 100 mm x 1000 mm) along with 100 mm x 100 mm x 300 mm corbel were modelled. Specimen N-A1 was analyzed as a control column. Three columns were modeled as structurally deficient columns (N-A2, N-A3, N-A4). Meshing with appropriate mesh attributes was carried out as shown in Fig. 5. Newton-Raphson nonlinear analysis was performed on all specimens to capture the first crack load. Similar columns were strengthened using shell93 elements (N-A2S, N-A3S, and N-A2S) and analysis was repeated until the failure of the specimens (Fig. 6).

Results and discussion

Structurally deficient columns were applied with load up to the first few cracks. then repaired, retrofitted, cured, and loaded under axial loading. Similar columns were analysed using ANSYS 14.0. The load-deflection, ductility ratio, energy ductility, stiffness, toughness, cracking pattern, and stress contours were the different parameters considered for the study and the results were compared.

Load deflection behaviour

Experimental and numerical values of the load-deflection behavior of the columns are compared in Fig. 7 The load resisted by columns is compared in Table 9. A comparison of the values showed that strengthening has enhanced the ultimate load for A2 and A3 by 2.36 and 2.52 times, than control column A1.

Similar behavior was reported from numerical results, the improvement was 2.33 and 2.48 times, compared to N-A1. Based on the eariler report39,48,49,50,51 states that the effect of CFRP wrapping was efficient in enhancing the compressive strength of short columns, for axial and less eccentric loading.

Even a single layer of GFRP wrapping8 improved the strength of columns cast with an aspect ratio of 1.0. Similarly, found that GFRP wrapping9,52 of reinforced concrete columns under axial loading increased the ultimate strength. Also confirmed that GFRP wrapping53 in the shear region of high-strength fiber RC beams enhanced the ultimate strength. It is found that the numerical analysis of FRP-wrapped columns29 showed enhanced ultimate strength. But in the present study, it was found that a single layer of wrapping could only restore the strength characteristics of the grade-deficient (A4) columns. In a similar case, the increased number of layers of wrapping recommended to have increased compressive strength10.

Stiffness modulus

Resistance of the structural components to the applied loading is quantified through stiffness modulus. The stiffness modulus of columns is compared in Fig. 8 Comparing the stiffness of the control column E-A1, strengthened columns showed enhancement in stiffness of about 114.06%, 89.75%, and 14.19% for E-A2S, E-A3S, and E-A4S respectively. Similar results were reported12. It was found that the stiffness of the shear wall was improved by providing four layers of fabric, bonded using the cementitious binder.

Corresponding improvements from the numerical analysis were reported as 120.5%, 100.1%, and 19.95% for N-A2S, N-A3S, and N-A4S respectively. A similar numerical analysis carried54 that prefabricated HSPRCC cement-based composite sheets improved the stiffness modulus of deficient columns.

Toughness modulus

The energy absorbed by the columns up to failure is evaluated through the toughness modulus. Toughness moduli for the columns are compared in Fig. 9 Energy absorption was highly improved in EA2S and EA3S due to strengthening. The retrofitting of partially damaged beams showed improved toughness due to retrofitting6. Similar behavior was noticed in the present study, for both main bar deficient (NA2S) and stirrup deficient (NA3S) columns. Whereas wrapping could not improve the toughness of grade deficient column (A4S). It was reported55, to improve the toughness modulus of reinforced columns, an increased number of layers of Textile Reinforced Mortar (TRM) jacketing was required.

Ductility behavior

Energy ductility is quantified through the ratio of toughness modulus calculated up to ultimate load to that calculated up to yield load. Energy ductility for the columns is compared in Fig. 10. Compared to E-A1, percentage improvement in energy ductility for E-A2S, E-A3S, and E-A4S were 77.36%, 42.95%, and 15.7% respectively. Similar behaviour was reported10,48. It was found that FRP confinement of normal strength concrete columns enhanced the ductility, under axial loading.

Similarly, confirmed that increased wrapping height enhanced the ductility of RC columns56. The failure of both concrete and rebars was delayed due to carbon fiber wrapping, confirming the enhancement of ductility of tested columns49. The increasing the layers for wrapping improved the ductility of axially loaded columns. Omarchaallal7 found that increased layers of wrapping improved the ductility of low-strength concrete columns. Corresponding enhancement for ductility from numerical results were 64.12%, 44.16%, and 23.14% for N-A2S, N-A3S and N-A4S columns. Earlier numerical studies57,58 also reported an improvement in ductility for strengthened specimens.

Failure pattern

Loading of columns E-A1, E-A2S, E-A3S, and E-A4S showed that failure is at the support region due to stress concentration and wrapping was intact without any delamination. Similar behavior was reported10 It was reported that even under ultimate load, the cover concrete was intact in the column, without any spalling and the confinement was effective without any debonding. In other research works carried18,59,60 out earlier, it was found that debonding of composite wrapping occurred with the usage of other organic binders.

The crack pattern and stress values of strengthened columns were compared with unstrengthened columns in Figs. 11a–d and 12a–d respectively. Similar results were reported8,30 that failure of wrapped columns occurred near the ends, followed by crushing and separation of concrete. In the present analysis, the strengthening showed improved first crack load and the first crack appeared from the base and progressed toward the end of the column. Stress values were increased by 10-15 times for strengthened columns N-A2S and N-A3S, compared to unstrengthened columns (N-A1). The corresponding increment in strain values for N-A2S and N-A3S was 5–10 times. Earlier studies11 reported that wrapping resulted in about 124% increase in ultimate compressive strain in eccentrically loaded columns. The grade deficient column (N-A4S) showed a less enhancement of 1.25 times, for stress values.

Due to stress accumulation at the base, the crushing of retrofitted columns occurred at the base50. It was found that the provision of a double layer for confinement increased the stiffness of the composites, resulting in the crushing failure of concrete. Studies have reported that columns retrofitted with GFRP exhibited sudden brittle failure accompanied by an explosive sound52. High-stress concentration resulted in the tearing of FRP composites. In the present work, the higher stress value in strengthened column A3S showed that the fiber composite took an additional load after the concrete had reached the ultimate stress value.

Analytical equations for confinement ratio (ACI 318, Yung-Chih Wang)

The compressive load-carrying capacity of both unconfined and confined columns was calculated based on ACI 318 and design equations61. The parameters calculated for various columns are displayed in Table 10 and Table 11. The values from design equations are compared with those of experimental and numerical values in Fig. 13 and the confinement ratio is compared in Fig. 14. The confinement ratio (CR) values show that the confinement was effective for A2 and A3 columns. Whereas for A4 columns the confinement has restored the columns to resist the load higher than the unconfined columns.

Conclusion

Experimental and numerical analysis of strengthened preloaded structurally deficient square reinforced concrete columns was carried out. Based on the results obtained following conclusions were arrived.

-

Retrofitting has enhanced the ultimate load for E-A2S and E-A3S columns. The increment was noticed as 2.36 and 2.52 times the value for the E-A1 control column. A similar improvement of 2.33 and 2.48 times was noticed for N-A2S and N-A3S columns compared to the control column N-A1

-

Compared to control column E-A1, percentage increase in stiffness modulus for E-A2S, E-A3S, and E-A4S were 114.06%, 89.75%, and 14.19% respectively. Corresponding increment for N-A2S, N-A3S, and N-A4S were 120.5%, 100.1%, and 19.95% respectively , compared to control column N-A1

-

In the case of toughness modulus similar behavior was noticed from experimental and numerical results. There was significant improvement for E-A2S, E-A3S, N-A2S, and N-A3S columns, compared to the control column

-

Enhancement in energy ductility was 77.36%, 42.95%, and 15.7% for E-A2S, E-A3S, and E-A4S columns, compared to the control column E-A1. Corresponding increment for N-A2S, N-A3S, and N-A4S were 64.12%, 44.16%, and 23.14% respectively compared to N-A1

-

All the columns N-A2S, NA3S, N-A4S failed due to stress concentration and simultaneous crack formation at the ends, without any debonding of fiber composite

-

The stress value for N-A2S and N-A3S columns was increased by 10-15 times more than the N-A1 column. The higher stress value shows that the confinement offered by fiber composite was efficient to take additional load, at the instant when concrete has attained the ultimate stress value The parametric analysis shows that confinement provided by GFRECC retrofitting was effective for damaged reinforced concrete columns with inadequate reinforcement. Whereas increasing the number of layers of the sheet along with the varied orientation of the fiber sheet may lead to positive results for axial loading of preloaded and repaired low-grade columns.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- f :

-

Applied stress in the material (MPa)

- \(E_a\) :

-

Modulus of elasticity or initial stiffness of the material (MPa)

- \(\varepsilon\) :

-

Strain corresponding to the applied stress f (dimensionless)

- \(\varepsilon _0\) :

-

Reference strain at which the peak stress \(f_a\) occurs (dimensionless)

- \(f_a\) :

-

Maximum or peak stress attained by the material (MPa)

- \(f_t\) :

-

Tensile strength of concrete (MPa)

- \(f_{ck}\) :

-

Characteristic compressive strength of concrete (MPa)

References

Xiao, Y. & Wu, H. Compressive behaviour of concrete confined by carbon fiber composite jackets. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 12, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2000)12:2(139) (2000).

Antonopoulos, C. & Triantafillou, T. Experimental investigation of frp-strengthened rc beam-column joints. J. Compos. Constr. 7, 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2003)7:1(39) (2003).

Pantelides, C., Okahashi, Y. & Reaveley, L. Seismic rehabilitation of reinforced concrete frame interior beam-column joints with frp composites. J. Compos. Constr. 12, 435–445. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2008)12:4(435) (2008).

Ilki, A., Bedirhanoglu, I. & Kumbasar, N. Behaviour of frp retrofitted joints built with plain bars and low-strength concrete. J. Compos. Constr. 15, 312–326. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CC.1943-5614.0000156 (2011).

Obaidat, Y. T., Heyden, S., Dahlblom, O., Abu-Farsakh, G. & Abdel-Jawad, Y. Retrofitting of reinforced concrete beams using composites laminates. Constr. Build. Mater. 25, 591–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.06.082 (2011).

Haddad, R., Al-Rousan, R. & Al-Sedyiri, M. Repair of shear deficient and sulphate damaged concrete beams using frp composites. Eng. Struct. 56, 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2013.05.007 (2013).

Chaallal, M. O., Shahawy, M. & Hassan, M. Performance of axially loaded short circular columns strengthened with carbon fiber-reinforced polymer wrapping. J. Compos. Constr. 7, 200–208. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2003)7:3(200) (2003).

Kumutha, R., Vaidyanathan, R. & Palanichamy, M. Behaviour of reinforced concrete rectangular columns strengthened using gfrp. Cement Concr. Compos. 29, 609–615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2007.03.009 (2007).

Ilki, A., Peker, O., Karamuk, E., Demir, C. & Kumbasar, N. Frp retrofit of low and medium strength circular and rectangular reinforced concrete columns. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 20, 169–188 (2008).

Eid, R., Roy, N. & Paultre, P. Normal- and high-strength concrete circular elements wrapped with frp composites. J. Compos. Constr. 13, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2009)13:2(113) (2009).

El Maaddawy, T. Strengthening of eccentrically loaded reinforced concrete columns with fiber-reinforced polymer wrapping system: Experimental investigation and analytical modeling. J. Compos. Constr. 13, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2009)13:1(13) (2009).

Trapko, T. Behaviour of fiber reinforced cementitious matrix strengthened concrete columns under eccentric compression loading. Mater. Des. 54, 947–954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2013.09.008 (2014).

Kurt, S. & Balaguru, P. Comparison of inorganic and organic matrices for strengthening of rc beams with carbon sheets. J. Struct. Eng. 127, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9445(2001)127:1(35) (2001).

Badanoiu, A. & Holmgren, J. Cementitious composites reinforced with continuous carbon fibres for strengthening of concrete structures. Cement Concr. Compos. 25, 387–394 (2003).

Bournas, D. & Triantafillou, T. Innovative seismic retrofitting of old-type rc columns through jacketing. textile-reinforced mortars (trm) versus fiber-reinforced polymers (frp). In Proceedings of the 14th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, 1–8 (Beijing, China, 2008).

Täljsten, B. & Blanksvärd, T. Mineral-based bonding of carbon frp to strengthen concrete structures. J. Compos. Constr. 11, 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2007)11:2(120) (2007).

Blanksvärd, T., Täljsten, B. & Carolin, A. Shear strengthening of concrete structures with the use of mineral-based composites. J. Compos. Constr. 13, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2009)13:1(25) (2009).

Toutanji, H. & Deng, Y. Comparison between organic and inorganic matrices for rc beams strengthened with carbon fiber sheets. J. Compos. Constr. 11, 507–513. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2007)11:5(507) (2007).

Wu, H., Sun, P. & Teng, J. Development of fiber-reinforced cement-based composite sheets for structural retrofit. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 22, 572–579. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0000056 (2010).

y Basalo, F. J., Matta, F. & Nanni, A. Fiber reinforced cement-based composite system for concrete confinement. Constr. Build. Mater. 32, 55–65 (2012).

Bhuvaneshwari, P. & Mohan, K. S. Strengthening of shear deficient reinforced concrete beams retrofitted with cement based composites. Jordan J. Civ. Eng. 9, 59–70 (2015).

Bhuvaneshwari, P. & Saravana Raja Mohan, K. Strength analysis of reinforced concrete beams affected by fire using glass fiber sheet and pp fiber ecc as binders. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. 8, 579–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40996-016-0029-9 (2017).

Mohammedameen, A., Çevik, R., Alzeebaree, A., Nis, M. & Gulsan, M. Performance of frp confined and unconfined engineered cementitious composite exposed to seawater. J. Compos. Mater. 53, 4285–4304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021998319857110 (2019).

Palanivelu, R., Panchanatham, B. & Eszter, L. E. Strengthening of axially loaded rc columns using frp with inorganic binder: A review on engineered geopolymer composites (egc). Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 23, e01803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e01803 (2025).

Yuan, W., Han, Q., Bai, Y., Du, X. & Yan, Z. Compressive behavior and modelling of engineered cementitious composite (ecc) confined with lrs frp and conventional frp. Compos. Struct. 272, 114200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2021.114200 (2021).

Dang, Z., Feng, P., Yang, J. & Zhang, Q. Axial compressive behavior of engineered cementitious composite confined by fiber-reinforced polymer. Compos. Struct. 243, 112191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112191 (2020).

Wang, J., Xia, J., Chang, H., Han, Y. & Yu, L. The axial compressive experiment and analytical model for frp-confined gangue aggregate concrete. Structures 36, 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2021.12.013 (2022).

Hariaravind, G. et al. Behaviour of frp-ecc-hsc composite stub columns under axial compression: Experimental and mathematical approach concrete filled steel tubular columns. Constr. Build. Mater. 408, 133707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133707 (2023).

Hajsadeghi, M. & Alae, F. Numerical analysis of rectangular reinforced concrete columns confined with frp jacket under eccentric loading. In 5th International conference on FRP composites in Civil Engineering (Beijing, China, 2010).

Al-Amin, S. & Ahsan, R. Finite element modelling of reinforced concrete column under monotonic lateral loads. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 42, 53–58. https://doi.org/10.5120/5676-6412 (2012).

Santhakumar, R., Chandrasekaran, E. & Dhanaraj, R. Analysis of retrofitted reinforced concrete shear beams using carbon fiber composites. Electron. J. Struct. Eng. 4, 66–74. https://doi.org/10.56748/ejse.442 (2004).

Dahmani, L., Khennane, A. & Kaci, S. Crack identification in reinforced concrete beams using ansys software. J. Strength Mater. 42, 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11223-010-9212-6 (2010).

Majeed, H. Q. Nonlinear finite element analysis of steel fiber reinforced concrete deep beams with and without openings. J. Eng. 18, 1421–1438 (2012).

Bhuvaneshwari, P., Vijay Mannaar, S. & Saravana Raja Mohan, K. Numerical analysis of strengthening of fire damaged rc columns using gfrp and pp fibre based cementitious composites. Chem. J. 8, 1296–1303 (2015).

Naser, M., Hawileh, R. & Abdalla, J. Fiber-reinforced polymer composites in strengthening reinforced concrete structures: A critical review. Eng. Struct. 198, 109542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2019.109542 (2019).

Choi, D., Hong, S., Lim, M. K., Ha, S. S. & Vachirapanyakun, S. Seismic retrofitting of rc circular columns using carbon fiber, glass fiber, or ductile pet fiber. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 15, 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40069-021-00484-7 (2021).

Khan, A. & Fareed, S. Behaviour of recycled aggregate rc columns wrapped with cfrp under axial compression. In Ilki, A., Ispir, M. & Inci, P. (eds.) 10th International Conference on FRP Composites in Civil Engineering. CICE 2021, vol. 198 of Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, 475–486, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-88166-5_46 (Springer, Cham, 2022).

Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318-19) and Commentary (American Concrete Institute, Farmington Hills, MI, 2019).

Lu, S., Wang, J., Yang, J. & Wang, L. Numerical analysis of preloaded frp-strengthened concrete columns under axial compression. Constr. Build. Mater. 357, 129297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129297 (2022).

Specification for 53 Grade Ordinary Portland Cement (Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, 2013). IS 12269:2013.

Specification for Coarse and Fine Aggregates from Natural Sources for Concrete (Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, 1970). IS 383:1970.

Recommended Guidelines for Concrete Mix Design (Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, 2009). IS 10262:2009.

Zhang, R., Matsumoto, K., Hirata, T., Ishizeki, Y. & Niwa, J. Shear behavior of polypropylene fiber reinforced rcc beams with varying shear reinforcement ratio. J. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. 2, 39–53. https://doi.org/10.2208/journalofjsce.2.1_39 (2014).

Mohammed, T. J., Abu-Bakar, B. & Bunnori, M. Strengthening of reinforced concrete beams subjected to torsion with uhpfc composites. Struct. Eng. Mech. 56, 123–136. https://doi.org/10.12989/sem.2015.56.1.123 (2015).

Vasudevan, G. & Kothandaraman, S. Rc beams retrofitted using external bars with additional anchorages-a finite element study. Comput. Concr. 16, 415–428. https://doi.org/10.12989/cac.2015.16.3.415 (2015).

Plain and Reinforced Concrete - Code of Practice (Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, 2000). IS 456:2000.

Kachlakev, D., Miller, T., Yim, S., Chansawat, K. & Potisuk, T. Finite element modeling of reinforced concrete structures strengthened with frp laminates. Tech. Rep. SPR316, Oregon Department of Transportation (2001).

Siddiqui, N. A., Alsayed, S. H. & Yousef, A. Experimental investigation of slender circular rc columns strengthened with frp composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 69, 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.07.053 (2014).

Muhammad, I. Axial and flexural performance of square rc columns wrapped with cfrp under eccentric loading. J. Compos. Constr. 16, 640–657. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CC.1943-5614.0000301 (2012).

Ombres, L. & Verre, S. Structural behaviour of fabric reinforced cementitious matrix (frcm) strengthened concrete columns under eccentric loading. Compos. B Eng. 75, 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.01.042 (2015).

Abdel-Hay, A. S. Partial strengthening of r.c square columns using cfrp. HBRC J. 10, 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hbrcj.2014.01.001 (2014).

Palanivelu, R. & Panchanatham, B. Strength and durability characteristics of basalt fiber-based engineered geopolymer composites under elevated temperature. Matéria (Rio de Janeiro). 30, e20250066. https://doi.org/10.1590/1517-7076-RMAT-2025-0066 (2025).

Vinodkumar, M. & Muthukannan, M. Structural behavior of hfrc beams retrofitted for shear using gfrp laminates. Comput. Concr. 19, 79–85. https://doi.org/10.12989/cac.2017.19.1.079 (2017).

Bedirhanoglu, I. Prefabricated -hsprcc panels for retrofitting of existing rc members- a pioneering study. Struct. Eng. Mech. 56, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.12989/sem.2015.56.1.001 (2015).

Al-Salloum, Y. A., Siddiqui, N. A., Elsanadedy, H. M., Abadel, A. A. & Aqel, M. A. Textile-reinforced mortar versus frp as strengthening material for seismically deficient rc beam-column joints. J. Compos. Construct. 15(6), 920–933 (2011).

Abdel-Hay, A. S. Partial strengthening of rc square columns using cfrp. HBRC J. 10, 279–286 (2014).

Kheyroddin, A., Naderpour, H., Ghodrati Amiri, G. & Hoseini Vaez, S. Influence of carbon fiber reinforced polymer on upgrading shear behavior of rc coupling beams. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. 35, 155–169 (2011).

Greene, C. E. & Myers, J. J. Flexural and shear behaviour of reinforced concrete members strengthened with a discrete fiber reinforced polyurea system. J. Compos. Constr. 17, 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CC.1943-5614.0000308 (2013).

Bournas, D., Lontou, P., Papanicolaou, C. & Triantafillou, T. Textile-reinforced mortar (trm) versus frp confinement in reinforced concrete columns. ACI Struct. J. 104, 740–748. https://doi.org/10.14359/18956 (2007).

Babaeidarabad, S., De Caso, F. & Nanni, A. Out of plane behaviour of urm walls strengthened with fabric-reinforced cementitious matrix composites. J. Compos. Constr. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CC.1943-5614.0000457 (2014).

Wang, Y.-C. & Hsu, K. Design of frp-wrapped reinforced concrete columns for enhancing axial load carrying capacity. Compos. Struct. 82, 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2007.04.002 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere thanks to the laboratory facilities provided by the School of Civil Engineering, SASTRA Deemed University, Thanjavur, for carrying out this research work successfully.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ruba P.: conceptualization, writing review and editing, and visualization. Vigneshpandian G.V: Data curation, Formal analysis, and validation. Bhuvaneshwari P.: methodology, supervision and review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All authors have read, understood, and have complied as applicable with the statement on “Ethical responsibilities of Authors” as found in the instructions for authors and are aware that with minor exceptions, no changes can be made to authorship once the paper is submitted.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruba, P., Vigneshpandian, G.V. & Bhuvaneshwari, P. Strengthening of structurally deficient and partially damaged short square columns using GFRECC retrofit technique. Sci Rep 15, 33375 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17970-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17970-7