Abstract

One-step button percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (B-PEG) is a method for gastrostomy placement. Few studies have described complications associated with T-fasteners. This study aimed to assess the incidence and risk factors of post-gastrostomy T-bar retention. Children who underwent one-step button percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (B-PEG) placement in our tertiary center between 2009 and 2020 were included in this retrospective study. Patient characteristics, comorbidities, complications, and potential risk factors were analyzed. All post-procedure radiological examinations, T-bar numbers, and durations post-procedure were collected. T-bar retention was considered at least one T-bar after 6 weeks post-B-PEG. A total of 679 children (337 boys; median age at B-PEG, 1.7 years) were included. Among 483 patients with radiological examinations analyzed, 361 (74.7%) had at least one T-bar impaction at the first radiological examination (median time after B-PEG, 0.55 years). Younger age at B-PEG was a risk factor for T-bar impaction (odds ratio [OR]: 2.82, 95% confidence interval [CI]: [1.71–4.66], P < .0001). Nearly 75% of children presented T-bar impaction. These data indicate that to avoid gastropexy complications, discussion of early removal of T-fasteners post-B-PEG is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nutritional support is crucial to preventing malnutrition and its associated complications in chronic pediatric diseases. When enteral nutrition dependence extends beyond 1–2 months1, gastrostomy is indicated. One-step button percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (B-PEG) has emerged as the preferred method for pediatric gastrostomy placement because it offers a lower rate of complications2,3,4 and is more acceptable to both children and their parents5.

The B-PEG push technique was first described in the early 1990s6. This method was updated and has been fully available since 2008 through the development of an introducer kit (Kimberly-Clarck, Roswell, GA, USA®). This kit allows insertion of a button over a guide, directly into the stomach under endoscopic guidance, after placement of three gastropexies.

Gastropexy, a critical aspect of the B-PEG procedure, is achieved using three T-fasteners (Saf-T-Pexy T-Fastener®; Kimberly-Clark). These T-fasteners are preloaded gastrointestinal suture anchor systems consisting of a metal bar with a resorbable suture and external bolster. The T-fasteners are inserted into the stomach under endoscopic control, and the metal bar unfolds in the gastric lumen. The anchors are left in place until the sutures resorb, releasing them into the gastric lumen and subsequently passing through the bowel. Gastropexies are important for securing the stomach wall to the abdominal wall and skin to prevent stomach detachment, which could lead to severe complications such as stomach leakage and peritonitis7.

However, complications associated with gastropexy anchors, including puncture site pain, granulomas, and T-bar extrusions, have been documented4,7,8. A few series have reported T-bars impactions within the gastric or abdominal wall9 over several weeks to months10, but to our knowledge, no studies have explored long-term impactions. Given this background, the present study aimed to investigate the incidence and complications of T-bar retention after gastrostomy.

Methods

This was a secondary data analysis from our previous study of long-term experience with the one-step push gastrostomy technique11. Informed consent was obtained from each patient’s parents or legal guardian. All data were anonymized. This study was approved by the French Data Protection Authority (DEC24-145) and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

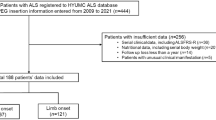

All data from clinical records of children aged < 18 years who had undergone B-PEG placement between 2009 and 2020 at our tertiary center were included. B-PEG was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using three gastropexy T-fasteners. Patient characteristics, comorbidities, and complications through the most recent follow-up were collected from medical records. Undernutrition was defined as a weight for height z-score < 2 standard deviations for age and sex. The presence of T-fastener complications and proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment at the time of the procedure were also recorded.

Our primary goal was to assess the incidence of post-B-PEG T-bar retention in the gastric mucosa. As T-bar are radiopaque, we reviewed all post-B-PEG radiological examinations to determine the prevalence of T-bar impactions in the gastric mucosa and duration of persistence inside the gastrointestinal tract. The number of T-bars and duration from the procedure were recorded. Radiological examinations were performed for various clinical indications, including chest, abdominal, and spine X-rays, computed tomography scans, and opacifications exams. We analyzed all hospital electronic medical records using Picture Archiving and Communication System software (Philips IntelliSpace PACS Enterprise). According to our local protocol, parents were systematically informed that following the B-PEG procedure, external bolsters were expected to dislodge within 6 weeks. They were specifically instructed to contact us if this did not occur.

T-bar retention was defined by the presence of at least one T-bar on a radiological examination more than 6 weeks post-gastrostomy. The first radiological examination was defined as the first imaging performed after B-PEG. The dates of subsequent radiological examinations (hereafter referred to as Examinations 2 and 3) were also collected to track the development of T-bar presence or absence over time.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies (percentages) and continuous variables as means ± standard deviation, or medians [interquartile range (IQR)] in cases of a nonnormal distribution. Normal data distributions were checked graphically and with the Shapiro–Wilk test. The rate of T-bar retentions, associated with gastropexy anchors, at 6 weeks post-B-PEG is described with its [95% confidence interval (CI)].

We evaluated the associations between patient characteristics and B-PEG procedure parameters, as well as retention of T-bars, using logistic univariate regression modeling. Factors with p < .05 were included in a multivariable model, except for suture lockers, as there were too many missing data on this variable. For continuous variables, the log-linearity assumption was verified using restricted cubic spline functions. Results are expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Statistical testing was done at the two-tailed α level, and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software package (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Sample characteristics

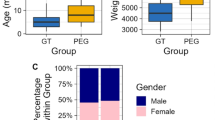

In total, 679 patients (337 boys [49.6%]; median age, 1.7 years; IQR [0.7–6.9]; age range, 0.6 months to 17.7 years) with a median weight of 9.2 kg (IQR [6.2–17.5]; range, 2.8–57.2 kg) at B-PEG were analyzed in the present study. At B-PEG placement, 238 children (35%) included were under 1 year of age.

Among this sample, 207 children were undernourished at B-PEG (35.9%, 103 with missing data). B-PEG was indicated for nutritional reasons in 660 (97.2%) patients. The most common pathology was neurological disorders (43.2%, median age, 3.52 years [IQR [1.47–10.75]). There were 135 patients (30.6%) with at least one anchor complication, including granuloma, pain, T-bar transcutaneous migration, or aseptic abscesses (Fig. 1).

Duration and T-bar persistence

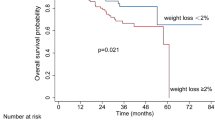

Follow-up radiological examinations was unavailable for 196 patients. A total of 361/483 (74.7%; 95% CI: 70.87–78.62) patients had at least one T-bar retained (Fig. 2) at the first radiological examination, which was performed at least 6 weeks post-B-PEG (Fig. 3).

Among patients with T-bar retention, the median duration between B-PEG and the first radiological examination (examination 1) was 0.6 years (IQR [0.3–2.0]; range, 6 weeks to 12.7 years). Among the 122 patients without T-bar retention, the median duration from B-PEG to first radiological examination was 0.67 years (IQR [0.5–0.8]).

The respective median durations between examinations 1 and 2, and between examinations 2 and 3, were 3.4 years (IQR [1.4–5.2]; range, 4 weeks to 11.24 years) and 2.9 years (IQR [1.0–6.0]; range, 2 months to 10.4 years).

Among the 361 patients with a T-bar retained on examination 1, 209/232 (90%) still had a T-bar present at examination 2, and 19/27 (70.4%) at examination 3 (Fig. 3).

Number of T-fasteners retained

The number of T-bars seen on radiological examinations, dependent on the duration between the procedure and examinations, are shown in Fig. 4.

Six T-bars were observed on the image from one patient who had two successive B-PEG procedures.

Risk factors for T-bar persistence

Age < 1 year at gastrostomy was a significant risk factor for T-bar persistence (OR: 2.82 [1.71–4.66]) in the logistic univariate regression model. By contrast, neurological disorder was significantly protective against T-bar retainment on univariate analysis but not on multivariate analysis (Table 1). No other potential risk factors, including undernutrition or PPI treatment, were significantly associated with T-bar persistence. However, with marked data missing, suture lockers dropping after 2 weeks was also a significant risk factor for T-bar persistence (Table 1).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first pediatric study to report T-bar retention several years post-B-PEG, which was associated with a higher risk of complications (e.g., transcutaneous migration, granuloma) (Fig. 1). Sydnor et al.9 demonstrated, in 71 patients, that more than half of T-bars migrated after more than 3 months, with most migrations occurring within the first 4 weeks; however, they did not assess longer-term follow-up.

Herein, nearly 75% of children had at least one T-bar retained in the abdominal or gastric wall. This could be explained by the fact that in our center, suture locks are not removed if they do not spontaneously drop before 6 weeks, consistent with the manufacturer’s protocol. The notion is that cutting suture lockers earlier would prevent gastric retention of the T-bar and reduce complications. The optimal timing for cutting T-fasteners remains unclear. From one perspective, T-fasteners permit the gastropexy to secure the stomach to the abdominal wall until adherences between the stomach and abdominal wall are fixed, avoiding major complications such as peritonitis and accidental intraperitoneal button migration7. Yet, removing suture locks in the first few weeks post-procedure appears to reduce the retention of T-bars and associated complications10,12. A Norwegian study in adults reported that the rate of migrated T-bars was significantly reduced when cutting suture locks after 2 weeks, compared with 3–4 weeks, postoperatively12. Controversially, two other studies showed no difference in complication rates between immediate T-fastener removal and removal at 2 days post-gastropexy13,14. However, these studies included only adults and had a short follow-up period of only 1–2 months.

A 2011 porcine study examined the characteristics of gastropexy at 1-, 2-, and 3-weeks post-procedure through fluoroscopic evaluation and histological analysis, revealing comparable outcomes among the examination weeks. That group observed that no T-bars were retained once the absorbable sutures were released15.

Herein, early suture lock removal (before 2 weeks) appears to protect against T-bar migration. However, numerous data were missing from this analysis, particularly regarding the exact timing to the external bolster falling out. It would be of interest to conduct a prospective study comparing complication rates, including T-bar persistence, after cutting the anchors after 2–4 weeks.

In this study, we found that infants aged < 1 year presented an increased risk of T-bar migration, possibly because of their thinner tissue layers compared with older children10, or because of their higher degree of tension during the B-PEG procedure.

Controversially, patients with neurological disorders had a trend of fewer T-fastener complications and less gastric or abdominal wall impaction. This could be explained by the reduced mobility among most of these patients, which may lead to less tension and traction on the anchors post-B-PEG.

Our findings also indicate that T-bars may be retained in the gastric or abdominal wall for several years, with a maximum follow-up of 12.7 years in one case. The T-bar is a foreign body, similar to a surgical clip. Even if complications appear minor, it is prudent to investigate whether this persistence leads to long-term complications such as pain, discomfort, or late migration.

Several procedural measures could reduce T-fastener complications: (1) during B-PEG placement, applying less traction in T-fasteners, and (2) removing the external bolster earlier, at 2 or 4 weeks post-procedure. The efficacy of such measures should be evaluated through appropriate studies. In our study, suture lockers drop after 2 weeks was associated with T-bars retention, but this data could not be confirmed as there were too many missing data on this variable.

Finally, other gastropexy systems have been developed16,17,18. These should be studied to find a balance between effective gastropexy and reduction of minor long-term complications.

Our study has strengths and limitations. The retrospective design may have underestimated the prevalence of T-bar persistence, as some patients were followed at other hospitals or did not undergo radiological follow-up examinations. The strengths of the study include the relatively large cohort and the fact that all procedures were performed using the same protocol, with standardized follow-up.

In conclusion, the findings herein could be expected to prompt practice changes toward the systematic removal of T-fasteners after 2–4 weeks. It would be valuable to conduct a comparative study using the same criteria before and after the implementation of these practice changes to assess reduced T-bar impaction and complications, including gastrostomy leaks and peritonitis.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Homan, M. et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children: an update to the ESPGHAN position paper. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 73, 415–426 (2021).

Jacob, A. et al. Safety of the One-Step percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy button in children. J. Pediatr. 166, 1526–1528 (2015).

Cave, J. J. et al. Percutaneous endoscopic primary gastrostomy button (PEG-B) is safe and significantly reduces the need for general anaesthetic tube changes in children when compared to the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube (PEG-T): a prospective study. J. Pediatr. Endosc Surg. 1, 143–148 (2019).

Castrillo, A. et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with T-Fasteners versus pull technique: analysis of complications. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. a-2340-9475 https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2340-9475 (2024).

Brinkmann, J., Fahle, L., Broekaert, I., Hünseler, C. & Joachim, A. Safety of the one step percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (Push-PEG) button in pediatric patients. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 77, 828–834 (2023).

Ferguson, D. R., Harig, J. M., Kozarek, R. A., Kelsey, P. B. & Picha, G. J. Placement of a feeding button (‘one-step button’) as the initial procedure. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 88, 501–504 (1993).

Thornton, F. J. et al. Percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy with and without T-fastener gastropexy: a randomized comparison study. Cardiovasc. Intervent Radiol. 25, 467–471 (2002).

Ho, T. & Margulies, D. Pneumoperitoneum from an eroded T-fastener. Surg. Endosc. 13, 285–286 (1999).

Sydnor, R. H., Schriber, S. M. & Kim, C. Y. T-Fastener migration after percutaneous gastropexy for transgastric enteral tube insertion. Gut Liver. 8, 495–499 (2014).

Kvello, M. et al. Initial experience with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with T-fastener fixation in pediatric patients. Endosc Int. Open. 6, 179–185 (2018).

Jean-Bart, C. et al. Complications of one-step button percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 182, 1665–1672 (2023).

Dahlseng, M. O. et al. Reduced complication rate after implementation of a detailed treatment protocol for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with T-fastener fixation in pediatric patients: A prospective study. J. Pediatr. Surg. 57, 396–401 (2022).

Sanogo, M. L., Cooper, K., Johnson, T. D. & Shields, J. Removal of T-Fasteners immediately after percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement: experience in 488 patients. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 211, 1144–1147 (2018).

Foster, A. et al. Removal of T-fasteners 2 days after gastrostomy is feasible. Cardiovasc. Intervent Radiol. 32, 317–319 (2009).

Ci, M. et al. Evaluation of gastropexy and stoma tract maturation using a novel introducer kit for percutaneous gastrostomy in a Porcine model. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr 35, (2011).

Shastri, Y. M. et al. New introducer PEG gastropexy does not require prophylactic antibiotics: multicenter prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 67, 620–628 (2008).

Durgin, J. M. et al. The paired T-Fastener technique: A Bolster-Free gastropexy for laparoscopic gastrostomy tube placement. J. Laparoendosc Adv. Surg. Tech. 31, 1431–1435 (2021).

Seifarth, F. G., Dong, M. L., Guerron, A. D., Lozada, J. S. & Magnuson, D. K. Endoscopic gastrostomy button with double-lasso U-stitch in children. JSLS 19, (2015).

Funding

No financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Juliette Viart, Maxime Leroy, and Frédéric Gottrand contributed to the study conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Juliette Viart and Frédéric Gottrand and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Viart, J., Antoine, M., Aumar, M. et al. Gastropexy device impaction in children with push percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Sci Rep 15, 34605 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18169-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18169-6