Abstract

To assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) regarding cervical spondylosis (CS) among the general public in China, and to identify factors associated with these KAP components. This cross-sectional study was conducted between January and June 2023 among general public, using a self-designed questionnaire. A total of 536 valid questionnaires were included. The KAP scores were 6 (5–7) for knowledge, 25 (24–39) for attitude, and 25 (23–29) for practice, respectively. Spearman correlation analysis showed positive correlation between knowledge and attitude (r = 0.093, P = 0.030), between knowledge and practice (r = 0.325, P < 0.001). Multivariate analysis showed that sitting time per day (OR 0.371, P = 0.020), household income above 5,000 Yuan per month (OR 0.488 ~ 0.555, P < 0.05), and unclear family history of CS were statistically associated with knowledge. Education (OR 3.577, P = 0.027), household income above 10,000 Yuan per month (OR 2.417, P = 0.012) were independently associated with attitude. Knowledge (OR 1.491, P < 0.001), middle aged participants (OR 1.918, P = 0.011) were independently associated with practice. The general public showed relatively adequate knowledge, and moderate attitude and practice towards CS. Associations were observed between KAP and demographic factors. Due to the cross-sectional design, causality cannot be established. Therefore, implications for health education should be viewed as preliminary and require confirmation through larger, multi-center, longitudinal studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical spondylosis (CS), also known as cervical osteoarthritis or degenerative disc disease of the neck leading to formation of osteophytes, disc herniation, and spinal canal narrowing1. It is an age-related degeneration of the cervical spine that involves the wear and tear of the intervertebral discs, facet joints, and ligaments2. General symptoms of this condition include neck pain, stiffness, limited neck motion, radiculopathy (pain down the arms due to nerve root compression), and myelopathy (weakness, balance impairments, and coordination difficulties)3,4. These clinical manifestations highlight the need to understand the underlying mechanisms and contributing factors of the disease. The underlying pathophysiology of CS involves altered disc cell metabolism, loss of disc height, reduced hydration, and increased collagen content. In addition, inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α, as well as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), contribute to extracellular matrix degradation and accelerated intervertebral disc degeneration5.

It largely affects the aging population worldwide, thus emphasizing the importance of unveiling its background and etiology for developing effective management strategies. Studies have shown that various factors contribute to the development and progress of CS, including the natural wear and tear with aging, genetic predisposition, smoking, lifestyle, and occupational activities (like repetitive neck movement, sitting, heavy weight lifting, etc.)6,7,8. This condition is diagnosed through a detailed clinical history, physical examination, and imaging studies, such as X-ray9, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)10, and computed tomography (CT) scans11. It is managed through a multidisciplinary approach involving conservative measures (use of analgesics, non-steroidal drugs, muscle relaxants), medication, physiotherapy, and in severe cases, surgical interventions (discectomy, laminectomy, or spinal fusion)3. Cervical spine pathology is increasingly prevalent worldwide due to population aging, and it poses a growing public health burden. The World Health Organization projects that by 2050, 22% of the global population will be over 60, greatly increasing the risk of cervical degenerative diseases. Low- and middle-income countries face especially high rates of disability due to limited access to timely care. This highlights the need for improved public awareness and prevention strategies across diverse healthcare settings12. In China, a large-scale epidemiological study reported that approximately 17.6% of adults are affected by symptomatic cervical spondylosis, with even higher rates among office workers and elderly individuals13. These figures highlight the urgent need for public awareness, early prevention, and effective management of this degenerative condition.

The analysis of knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) towards a medical condition is important in medical field. KAP analysis is a useful tool for identifying the factors influencing behavior change14,15,16. These studies aim to understand the awareness, perception, and management of a specific medical condition. The knowledge dimension assesses the general knowledge of the population about the condition and its causes, symptoms, risk factors, and treatment options17. The attitude dimension assesses the general perception of the population towards the disease and its impact on daily life18. The practice dimension examines the approaches individuals take to prevent or manage the condition19. KAP studies aim to identify gaps in knowledge, negative attitudes, and ineffective practices that can be addressed through education or intervention programs20. These studies have shown that medical professionals may have had good knowledge about a disease, but their clinical practice and attitudes may need improvement. Physiotherapist may have adequate knowledge about a treatment21, but their attitude and practice vary22. Patients may have limited knowledge about non-surgical treatment, but their attitudes are generally positive. Access to healthcare facilities is often a barrier to appropriate management23. Understanding KAP can improve disease management and enhance attitudes and behavior towards the disease.

This study aimed to investigate KAP levels regarding cervical spondylosis among the general public in China and analyze associated sociodemographic and behavioral factors. The findings will inform the design of targeted health education programs and preventive interventions for cervical spondylosis. This research provides insights into awareness and understanding of cervical spondylosis and identifies existing attitudes and practices related to the condition. Such information can help develop targeted education campaigns and interventions to improve knowledge, change attitudes, and promote effective prevention and management practices. By addressing existing gaps, this study can contribute to more effective strategies for prevention and management. However, it does not evaluate whether improvements in KAP scores lead to measurable clinical benefits, such as reduced incidence, symptom severity, or disability related to cervical spondylosis. A clear theoretical framework linking KAP to health outcomes is needed to understand the potential impact of educational or behavioral interventions. Future research should integrate behavioral change theories and longitudinal designs to determine if enhanced KAP translates into improved cervical spine health and quality of life.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Dalian Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital, Dalian, China, between January 29, 2023 and June 22, 2023. Participants from the general public aged 18 years and above were included. Inclusion criteria were: (1) aged 18 years or above; (2) able to read and understand Chinese; and (3) voluntarily agreed to participate with informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: (1) individuals with diagnosed psychiatric disorders or cognitive impairments that may affect understanding of the questionnaire; (2) medical professionals or students majoring in health-related fields; and (3) incomplete or inconsistent questionnaire responses. The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Dalian Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital (January 3, 2023), and informed consent was obtained from the all participants involved.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was designed based on the guidelines provided by the Chinese Society of Rehabilitation Medicine: Guidelines for the Diagnosis, Treatment and Rehabilitation of Cervical Spondylosis (2010 Edition) and the North American Society for Spine Surgery: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Neurogenic Cervical Spondylosis (2010 Edition). A pilot study was conducted with 30 participants to assess the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value was 0.833, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (P < 0.001), indicating good structural validity for factor analysis. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.812, confirming acceptable internal consistency of the instrument.

The final version of the questionnaire was in Chinese and consisted of four dimensions with a total of 39 items. The sociodemographic characteristics section included 15 items, the knowledge dimension contained 8 items, the attitude dimension had 8 items, and the practice dimension included 8 items. In the knowledge dimension, questions with correct answers were assigned 1 point for a correct response and 0 points for a wrong or an unclear answer. For the attitude and practice dimensions, a five-point Likert scale was primarily used, ranging from very positive (5 points) to very negative (1 point) based on the level of positivity, resulting in scores ranging from 8 to 40 points. For interpretation purposes, we defined “relatively adequate” knowledge as achieving at least 70% of the maximum possible score in the knowledge dimension, consistent with prior KAP studies that have used similar thresholds for adequate knowledge classification16. In our questionnaire, the maximum possible knowledge score was 8, so a score of ≥ 6 was considered relatively adequate. This threshold allowed for a consistent and literature-based interpretation of participants’ knowledge levels.

To further evaluate construct validity, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Model fit was assessed using standard indices with the following a priori criteria for acceptable fit: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08, incremental fit index (IFI) > 0.80, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) > 0.80, and comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.80. The CFA yielded RMSEA = 0.078, IFI = 0.826, TLI = 0.869, and CFI = 0.824, supporting the factorial validity of the instrument.

Sampling procedure and data collection

A non-probability sampling technique was used. Specifically, convenience sampling was employed, and the questionnaire was distributed face-to-face to participants at the outpatient clinic site by five research assistants. Prior to distribution, the research assistants underwent internal training to ensure they fully understood the significance and importance of the questionnaires. They also familiarized themselves with the specifications for filling out the questionnaires and were trained in maintaining a polite and friendly manner during interactions with participants. During the collection of questionnaires, the research assistants carefully checked for any missing items. To ensure a large diverse sample size, the questionnaires were distributed to cover various age groups, genders, and occupations. Given the high number of people coming and going from the clinic, the questionnaires were distributed randomly face-to-face. Participants were provided a warm, quiet, and comfortable environment in a designated room to fill in the questionnaires. They were reminded to complete the questionnaires in a serious and factual manner with clear handwriting and not to feel apprehensive. To maintain the quality of the questionnaires, missing items were checked upon collection, and the questionnaires were properly numbered and preserved. During the data cleaning process, questionnaires with contradictory information were eliminated. Since participants were recruited at an urban hospital outpatient clinic, the sample may overrepresent individuals with access to healthcare and urban residents, and may not fully reflect the broader general population.

Sample size

The calculation of sample size was based on the following formula employed in the cross-sectional study

.

where n denotes the sample size. Besides, p value was assumed to be 0.5 to achieve the maximum sample size. α refers to the type Ⅰ error, which was set to 0.05 in this case. Subsequently, \(\:{Z}_{1-\frac{\alpha\:}{2}}\) was yielded 1.96. \(\:\delta\:\) represents the effect sizes between groups, which was determined as 0.05, and at least 384 participants should be required. As regards the 20% of non-response rate, a total of 480 participants are required to be involved.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. As all KAP scores (knowledge, attitude, and practice) did not follow a normal distribution (P < 0.001 for all variables), descriptive statistics were reported as median with interquartile range expressed as median (Q1–Q3). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages [n (%)]. To compare differences in KAP scores among subgroups with different sociodemographic characteristics, non-parametric tests were used: the Mann–Whitney U test for two-group comparisons, and the Kruskal–Wallis test for comparisons among three or more groups. Spearman correlation analysis was used to assess the relationships among knowledge, attitude, and practice scores. Additionally, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent factors associated with each of the KAP dimensions. A two-tailed P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Findings or results

The questionnaire was distributed among 536 participants, with a 100% return rate with their responses. The median (interquartile range) KAP scores were 6 (5–7) for knowledge, 25 (24–39) for attitude, and 25 (23–29) for practice, respectively, indicating sufficient knowledge, moderate attitude and practice. In addition, knowledge score was significantly varied by their education (P = 0.025), sitting time per day (P < 0.001), household income per month (P < 0.001), drinking (P = 0.004), family history (P < 0.001). Attitude scores were significantly varied by their age (P = 0.049), education (P < 0.001), sitting time per day (P = 0.007), household income per month (P < 0.001), CS or not (P < 0.001), family history (P < 0.001). Practice score was significantly varied by their age (P < 0.001), residence (P = 0.041), sitting time per day (P < 0.001), household income per month (P < 0.001), marital status (P = 0.031), smoking (P < 0.001), medical insurance (P = 0.009), CS (P < 0.001), and family history (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

The results on the distribution of correct, wrong, and unclear answers for questions K1-K8, indicating the level of knowledge about CS among the general public. The results show that majority of participants answered correctly to question K1-K7, ranging from 94.4 to 73.13%, while only 52.8% answered correctly for question K8. Only a small portion of participants answered ‘wrong’ (1.31–15.67%) and others answered ‘unclear’ (3.73–31.53%) to all questions (Table 2).

The results on the distribution of ‘Strongly agree’, ‘Agree’, ‘Neutral’, ‘Disagree’, and ‘Strongly disagree’ answers for questions A1-A8, indicate the attitude of general public towards CS (Table 3). The results reveal a wide spectrum of responses to the ‘agree’ option among participants. Notably, question A1, which pertained to the association of CS with work and lifestyle, garnered the highest agreement rate at 62.31%. In contrast, question A3, which focused on basic knowledge about CS, received the lowest agreement rate at 24.44%. Conversely, only a minority of participants (23.88%) expressed strong agreement with question A1, while an exceedingly small percentage (0.75%) disagreed with it. The ‘neutral’ response exhibited substantial variation among participants, ranging from 51.31% for question A2 (addressing the impact of physical stress on CS) to 27.61% for question A4 (centered on the belief in prevention as a key factor in dealing with CS). Notably, there were no participants who chose the ‘strongly disagree’ option for questions A1, A4, and A7 (related to CS patients actively seeking standardized treatment). However, a few individuals did strongly disagree with other questions.

The results from Table 4 indicate the distribution of responses for questions P1-P8, which assess the practice of CS among the general public. The findings reveal that the highest percentage of respondents answered ‘always’ for question P5 (16.04%), which pertains to the suitable height of a pillow, while the lowest percentage was recorded for question P8 (7.09%), which involves taking rest or seeking medical attention for neck discomfort. Question P5 also yielded the highest percentage of ‘often’ responses (36.38%), whereas question P4 had the lowest ‘often’ response rate (21.64%). For the ‘sometimes’ category, the largest percentage was found for question P6 (50.37%) regarding engagement in moderate exercises, whereas the lowest percentage was observed for question P1 (34.89%), which addresses seeking knowledge about preventing CS. When it comes to the ‘rarely’ responses, question P4 had the highest percentage (29.29%) concerning maintaining a parallel line of sight or a 5°-10° angle to the screen while using electronic devices. Conversely, the lowest ‘rarely’ response rate (5.97%) was recorded for question P5 relating to suitable pillow height. Lastly, the ‘never’ response rate was highest for question P8 (3.92%) concerning rest or medical attention for neck discomfort, while the lowest ‘never’ response rate (0%) was found for questions P5 and P6, which pertain to suitable pillow height and engagement in moderate exercises, respectively.

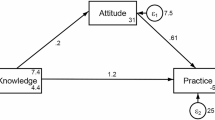

Spearman correlation analysis showed a weak positive correlation between knowledge and attitude (r = 0.093, P = 0.030) and a modest positive correlation between knowledge and practice (r = 0.325, P < 0.001) (Table 5). Multivariate regression analysis showed that sitting time per day (OR = 0.371, 95%CI: 0.16–0.858, P = 0.020), household income between 5000 and 10,000 (OR = 0.555, 95%CI: 0.317–0.972, P = 0.039) and above 10,000 (OR = 0.488, 95%CI: 0.242–0.984, P = 0.045), and unclear family history of CS were independently associated with knowledge (Table 6). Education (OR = 3.577, 95%CI: 1.157–11.056, P = 0.027), household income above 10,000 Yuan per month (OR = 2.417, 95%CI: 1.213–4.815, P = 0.012) were independently associated with attitude (Table S1). Knowledge (OR = 1.491, 95%CI: 1.264–1.759, P < 0.001), middle aged participants (OR = 1.918, 95%CI: 1.162–3.165, P = 0.011) were independently associated with practice (Table S2).

Discussion

This study found that general public in China might have sufficient knowledge, moderate attitude and practice towards CS. Various demographic characteristics such as age, education, sitting time per day, household income, and family history were found to be statistically associated with KAP. Given the cross-sectional nature of the study, these associations do not imply causation, and the observed relationships should be interpreted as correlations rather than direct causal effects. These findings suggest that targeted educational campaigns, programs, and interventions could be developed for CS prevention and management, while acknowledging the need for longitudinal research to clarify causal pathways. In light of these methodological constraints, recommendations for health education and prevention should be regarded as hypothesis-generating and subjected to pilot testing and rigorous evaluation before wider implementation. While our study provides valuable baseline data, caution is needed when extrapolating these results to the entire Chinese population. The relatively small and geographically limited sample may not fully reflect the diversity of demographic and behavioral characteristics present across the country. Future studies should include larger, more stratified samples from multiple regions to improve representativeness.

The younger individuals may be more proactive in implementing recommended practices for managing medical condition23. Residence was also found to be significantly associated with knowledge and practice scores, with participants living in rural areas having higher mean knowledge scores. This indicate that rural residents have more exposure to information or healthcare services, leading to a better understanding of the condition24. Education was significantly associated with KAP scores. Participants with postgraduate education were over three times more likely to have a more positive attitude toward CS (OR = 3.577), indicating a strong and clinically meaningful effect, possibly due to better health literacy and awareness. This suggests that higher levels of education may contribute to better knowledge, more positive attitudes, and better practice habits when it comes to managing a medical condition25. Sitting time was found to be significantly associated with knowledge and practice scores, with participants sitting for less than 4 h having the highest mean knowledge and practice scores. This indicates that individuals who spend less time sitting may have better knowledge and implement better practices for managing CS26. Household income significantly influenced KAP scores, with participants with a household income of more than 10,000 having the highest mean knowledge and attitude scores. This could be due to better access to healthcare resources and information among individuals with higher incomes27. Marital status showed a significant association with practice scores, with married participants having higher scores than unmarried. This suggests that married individuals have more support and motivation to engage in recommended practices for managing CS28. Drinking was significantly associated with knowledge scores, as reported previously29. Although the nature of this association is not clear from the given information. Further details from the study would be needed to understand the relationship between drinking and knowledge about CS. Medical insurance significantly influenced knowledge and practice scores, with participants having both social and commercial medical insurances having the highest mean scores. This indicates that having comprehensive medical insurance coverage may lead to better knowledge and adoption of recommended practices for managing a medical condition30. The presence of CS itself significantly influenced attitude and practice scores, with participants having confirmation of the condition having the highest attitude and practice scores. This suggests that individuals with a confirmed diagnosis of CS may have a better understanding of the condition and be more proactive in managing it. Family history was also significantly associated with KAP scores, which is in accordance with previous reports. Overall, these findings highlight the importance of considering various demographic factors when assessing KAP related to CS, which can help inform targeted interventions and educational strategies to improve outcomes for individuals with CS.

The results from the knowledge assessment on CS indicate that the majority of respondents have a good understanding of the condition. Most respondents correctly identified that CS is caused by degenerative changes in the cervical intervertebral discs and recognized the main symptoms of the condition, such as neck and back stiffness, pain, and radiating pain in the upper limbs3,4. They also acknowledged the variety of symptoms associated with CS, including numbness and weakness in the limbs, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, blurred vision, tachycardia, and difficulty swallowing17. Furthermore, the respondents were well aware of the causes of chronic strain of the cervical spine, with a large majority identifying poor sleeping positions, improper work and posture, excessive physical exercise, or neck movements as the main reasons31. They also recognized that both excessively high and low pillows can contribute to poor sleep posture. Additionally, the majority of respondents understood that poor posture during desk work or constantly looking down at a phone can lead to strain on the neck muscles and ligaments, increasing pressure on the cervical intervertebral discs31. They also correctly recognized that direct exposure to cold air from air conditioning is not a direct cause of CS32. However, there was some variation in responses to the question about the necessity of surgical treatment for a complete recovery from CS, with only about half of the respondents correctly understood that surgical treatment is not always necessary, and non-surgical treatment can provide relief33. Overall, these results suggest that the respondents generally have good knowledge of CS, but there may be some areas where further education or clarification is needed, particularly regarding the necessity of surgical treatment.

The results showed that CS is mainly related to work and lifestyle habits. This aligns with existing literature that highlights the role of occupational and lifestyle factors in the development of CS13. Psychological stress did not show any significant impact on CS; however, existing literature shows mixed findings regarding the association between psychological stress and CS34. The study showed a lack of knowledge towards CS, highlighting the need for more education and awareness about this condition among the general population. Studies have emphasized the importance of patient education and awareness programs for the prevention and management of CS19. Prevention is key in dealing with CS, highlighting the importance of preventive measures such as maintaining proper posture, regular exercise, and ergonomic adjustments in preventing CS31. The study showed varied response to treatment, indicating uncertainty or lack of awareness among respondents about the effectiveness of treatment options for CS. Existing literature suggests that treatment approaches for CS can vary and depend on the severity of symptoms and individual patient characteristics35. CS was shown to significantly impact work and quality of life. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have reported the negative impact of CS on work productivity and quality of life13. The participants with CS should actively seek standardized treatment. This highlights the importance of seeking appropriate medical care and adhering to recommended treatment guidelines for CS. Literature supports the use of evidence-based and standardized treatment approaches for better outcomes in CS8,35. A considerable portion of participants ignored this condition in case of no evident symptoms. This finding suggests a lack of proactive care-seeking behavior among respondents in the absence of symptoms. Studies have emphasized the importance of early detection and intervention for better management of CS33. In conclusion, these results highlight varying attitudes towards CS among respondents. These findings reflect the complexity of this condition and the need for comprehensive education, supportive interventions, and standardized care for better prevention and management of CS.

The study also investigated the impact of seeking knowledge, paying attention to posture and movement, avoiding certain behaviors, using electronic devices correctly, choosing suitable pillows, engaging in exercise, keeping the neck and shoulders warm, and addressing discomfort in the neck. Majority of respondents reported actively seeking knowledge on preventing CS, suggesting that a significant proportion of the respondents engage in behaviors related to acquiring knowledge about preventive measures for CS17. They get involve in standing up and moving their neck after sitting for a long time, indicating that they are aware of the importance of posture and movement in preventing CS. Some participants responded that they avoid lying in bed while reading, watching TV, or using a phone, indicating that they make efforts to avoid such behaviors which may contribute to CS. A small percentage of respondents reported that they always or often keep the line of sight parallel or at a 5°-10° angle to the screen when using electronic devices. This finding suggests that a majority of the respondents do not consistently follow this practice, which may increase the risk of CS. Many participants were using a suitable pillow height when sleeping, indicating that they are aware of the importance of pillow selection in preventing CS. Besides, they also engaging themselves in moderate exercise to prevent CS. Exercise has been reported as a preventive measure for CS36. Keeping the neck and shoulders warm to avoid direct exposure to air conditioning or fans in daily life is also a useful approach to prevent CS37,38,39. Addressing discomfort in the neck is also considered a proactive approach for preventing CS. These findings align with previous research on preventive behaviors for CS. For example, studies have found that practicing good posture31, regular exercise36, and avoiding excessive use of electronic devices were important preventive behaviors for CS. Other studies emphasized the importance of neck care practices, including pillow selection, avoiding prolonged static positions, and maintaining warmth in the neck and shoulder area32,38. These findings provide insights into various practices related to preventing CS which could be used in understanding and analyzing the behavior and attitudes of general public towards preventive measures for CS.

Spearman correlation analysis showed a weak positive correlation between knowledge and attitude, indicating that individuals with higher knowledge levels may hold more positive attitudes towards CS. This correlation is statistically significant but lacks practical significance, suggesting that increases in knowledge may not lead to meaningful attitude changes. Additionally, multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that knowledge was not an independent predictor of attitude, highlighting that knowledge alone may not influence attitudes without other factors. There was a moderate positive correlation between knowledge and practice, but it still represents a modest association with limited clinical implications. Conversely, attitude and practice showed a weak negative correlation, indicating that attitudes may have some influence on behavior, but this is not strong or significant. Other factors may be more influential in shaping behaviors or practices. These results align with findings from various studies. For example, a study on maternal health knowledge, attitude, and practice also found a positive correlation between knowledge and attitude, as well as between knowledge and practice39. Another study on hand hygiene knowledge, attitude, and practice among healthcare workers reported a significant positive correlation between knowledge and practice, but a weak negative correlation between attitude and practice40. These findings support the idea that knowledge plays a key role in shaping attitudes and practices, but attitudes may not always directly translate into behaviors. These findings have important implications for designing interventions and educational programs to improve individuals’ KAP related to CS. However, our findings were not directly compared with results from validated international KAP studies or interpreted within the context of established health behavior models, such as the Health Belief Model or Theory of Planned Behavior. Such comparisons could provide a broader perspective, highlight similarities or differences across populations, and improve the interpretability of our results. Although studies specifically examining KAP toward cervical spondylosis are limited, previous KAP research on chronic neck or musculoskeletal pain has revealed similar gaps between awareness and actual practice. For example, individuals may have general knowledge about posture and prevention but fail to implement recommended behaviors consistently32. While specific KAP studies on cervical spondylosis are limited, research on low back pain (LBP) offers valuable parallels. For instance, a study conducted in Malawi revealed that a significant proportion of patients with LBP lacked comprehensive knowledge about the condition and held negative attitudes, which adversely affected their management practices32. These findings underscore a common trend across musculoskeletal disorders: adequate knowledge does not always translate into positive attitudes or effective practices. This pattern aligns with our study’s observations on cervical spondylosis, emphasizing the need for targeted educational interventions that not only impart knowledge but also address attitudes and promote best practices. This study expands this area by focusing specifically on CS, and provides baseline data for future research and intervention planning in the general population. Educational and awareness campaigns can serve as critical tools in bridging the gap between knowledge and practice. Tailored health education interventions, delivered through schools, workplaces, or digital platforms, may effectively enhance public understanding and encourage behavior change related to cervical spine health. These suggestions are exploratory; their effectiveness should be tested in well-designed, theory-informed, and adequately powered studies. Nevertheless, without a clear theoretical framework connecting improved KAP to actual reductions in disease burden or functional impairment, the extent of potential clinical benefits remains uncertain.

The results of the multivariate regression analysis indicate that several factors are associated with KAP towards CS. The results show that education level is significantly associated with knowledge scores, with higher education levels are associated with a higher knowledge score on a medical condition41. Sitting time was also found to be significantly associated with knowledge scores, implying that prolonged sitting may be linked to lower knowledge about a medical condition42. Household income was another significant factor associated with knowledge scores, with higher household income was associated with a high knowledge score, suggesting that socioeconomic status plays a role in knowledge about CS. Participants with an unclear family history had a high knowledge score compared to those with no family history, suggesting that having a family history of CS is associated with higher knowledge about the condition. Education was also directly associated with the attitude of participants towards CS, as reported previously41. Participants with a household income above 10,000 Yuan had significantly more positive attitudes toward CS (OR = 2.417, P = 0.012), a result that suggests economic status has a meaningful impact, potentially through greater access to information, care, or health-promoting environments27. Furthermore, participants who were unwilling to disclose their household income had a significantly higher attitude score, suggesting that privacy concerns may have an impact on attitude towards CS. Knowledge remains significantly associated with practice scores (OR = 1.491, 95% CI: 1.264–1.759, P < 0.001), indicating a modest increase in the likelihood of engaging in preventive behaviors. However, the effect size was relatively small, suggesting that knowledge alone may not be sufficient to drive behavioral change without the support of other factors such as motivation, awareness, or healthcare accessibility. Age was also found to be significantly associated with practice scores, with middle-aged and elderly participants having higher scores compared to young participants, which is in accordance with previous reports33. Overall, these findings indicate that education level, sitting time, household income, family history, and age are important factors associated with KAP scores towards CS.

Although studies specifically examining KAP toward cervical spondylosis are limited, previous KAP research on chronic neck or musculoskeletal pain has revealed similar gaps between awareness and actual practice. For example, individuals may have general knowledge about posture and prevention but fail to implement recommended behaviors consistently43. While specific KAP studies on cervical spondylosis are limited, research on low back pain (LBP) offers valuable parallels. For instance, a study conducted in Malawi revealed that a significant proportion of patients with LBP lacked comprehensive knowledge about the condition and held negative attitudes, which adversely affected their management practices44. These findings underscore a common trend across musculoskeletal disorders: adequate knowledge does not always translate into positive attitudes or effective practices. This pattern aligns with our study’s observations on cervical spondylosis, emphasizing the need for targeted educational interventions that not only impart knowledge but also address attitudes and promote best practices. This study expands this area by focusing specifically on CS, and provides baseline data for future research and intervention planning in the general population. Educational and awareness campaigns can serve as critical tools in bridging the gap between knowledge and practice. Tailored health education interventions, delivered through schools, workplaces, or digital platforms, may effectively enhance public understanding and encourage behavior change related to cervical spine health. These suggestions are exploratory; their effectiveness should be tested in well-designed, theory-informed, and adequately powered studies. Nevertheless, without a clear theoretical framework connecting improved KAP to actual reductions in disease burden or functional impairment, the extent of potential clinical benefits remains uncertain. Future studies should incorporate established health behavior models, such as the Health Belief Model or Theory of Planned Behavior, to clarify mechanisms by which changes in KAP may influence preventive actions and clinical outcomes.

This study has a few limitations. First, the study was conducted at a single hospital in a specific city, using convenience sampling at the outpatient clinic, which may have introduced selection bias. The sample may overrepresent individuals with higher education levels, urban residence, and greater health awareness, thus limiting the representativeness and generalizability of the findings to the broader general population and other healthcare settings. Second, the study participants were recruited from the general public, which may introduce selection bias and limit the representativeness of the sample. Third, the cross-sectional design nature of the study making it difficult to establish causal relationship, or assess changes over time. Finally, the data collection relied on self-reporting, which may introduce recall bias or social desirability bias. In addition, some important potential confounders—such as physical activity level, specific occupational exposures, and comorbidities—were not included in the regression analysis due to data limitations. This may have influenced the observed associations and should be addressed in future studies through more comprehensive data collection and model adjustment. Consequently, the empirical basis for specific education strategies is limited; interpretation should be cautious until validated in multi-center, longitudinal research with stronger analytic designs. Additionally, the lack of direct comparison with international KAP studies or integration with recognized behavioral theories limits the contextual interpretation of our results. Incorporating such comparisons and theoretical frameworks would enhance understanding of how our findings align with or diverge from global KAP research patterns. Furthermore, the precision of certain odds ratio estimates was limited, as indicated by wide confidence intervals, reducing certainty of these associations. The categorization of continuous variables such as age and household income, while consistent with other KAP studies, lacked specific theoretical justification for cervical spondylosis and may have introduced bias. Future research should consider alternative analytic strategies that retain the continuous nature of these variables or use evidence-based cutoffs to enhance validity.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the general public in China showed relatively adequate knowledge and moderate levels of attitude and practice towards CS. Demographic and behavioral characteristics (e.g., age, education, sitting time per day, household income, and family history) were statistically associated with KAP; however, given the cross-sectional, single-site design and other methodological limitations, these findings should be considered preliminary. Any health education implications derived from this study are tentative and warrant confirmation through larger, multi-center, longitudinal studies before informing policy or practice.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dydyk, A. M., Khan, M. Z. & Singh, P. Radicular Back Pain. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Mohammad Zafeer Khan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Paramvir Singh declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. ( StatPearls Publishing LLC, 2023).

Nayak, B. & Vaishnav, V. A. D. & R. Y. An overview on cervical spondylosis. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 5312–5316 (2022).

McCormick, J. R., Sama, A. J., Schiller, N. C., Butler, A. J. & Donnally, C. J. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: A guide to diagnosis and management. J. Am. Board. Fam Med. 33, 303–313 (2020). 3rd.

Garg, K. & Aggarwal, A. Effect of cervical decompression on atypical symptoms cervical Spondylosis-A narrative review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 157, 207–217e201 (2022).

Choi, S. H. & Kang, C. N. Degenerative cervical myelopathy: pathophysiology and current treatment strategies. Asian Spine J. 14, 710–720 (2020).

Kanbara, S. et al. Zonisamide ameliorates progression of cervical spondylotic myelopathy in a rat model. Sci. Rep. 10, 13138 (2020).

Aljuboori, Z. & Boakye, M. The natural history of cervical spondylotic myelopathy and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: A review Article. Cureus 11, e5074 (2019).

Theodore, N. Degenerative cervical spondylosis. N Engl. J. Med. 383, 159–168 (2020).

Chen, X., Xue, P., Shi, Y. & Chen, S. The role of digital X-ray in curative effect and nursing evaluation of cervical spondylotic radiculopathy. J. Healthc Eng. 5666136 (2021).

Park, W. T. et al. High reliability and accuracy of dynamic magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a multicenter study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 23, 1107 (2022).

Schoenfeld, A. J. et al. Utility of adding magnetic resonance imaging to computed tomography alone in the evaluation of cervical spine injury: A propensity-matched analysis. Spine (Phila Pa) 43, 179–184 (2018).

Waheed, M. A. A. et al. Cervical spine pathology and treatment: a global overview. J. Spine Surg. 6, 340–350 (2020).

Lv, Y. et al. The prevalence and associated factors of symptomatic cervical spondylosis in Chinese adults: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 19, 325 (2018).

Palati, S. et al. Attitude and practice survey on the perspective of oral lesions and dental health in geriatric patients residing in old age homes. Indian J. Dent. Res. 31, 22–25 (2020).

Peng, Y. et al. A cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitude and practice associated with COVID-19 among undergraduate students in China. BMC Public. Health. 20, 1292 (2020).

Wani, R. T., Rashid, I., Nabi, S. S. & Dar, H. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of family planning services among healthcare workers in Kashmir - A cross-sectional study. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 8, 1319–1325 (2019).

Alsan, M. et al. Comparison of knowledge and Information-Seeking behavior after general COVID-19 public health messages and messages tailored for black and Latinx communities: A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 174, 484–492 (2021).

Freiermuth, C. E. et al. Attitudes toward patients with sickle cell disease in a multicenter sample of emergency department providers. Adv. Emerg. Nurs. J. 36, 335–347 (2014).

Salas-Zapata, W. A. & Ríos-Osorio, L. A. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of sustainability: systematic review 1990–2016. J. Teacher Educ. Sustain. 20, 46–63 (2018).

Bhalla, D. et al. Population-based study of epilepsy in Cambodia associated factors, measures of impact, stigma, quality of life, knowledge-attitude-practice, and treatment gap. PLoS One. 7, e46296 (2012).

Venkatakarthikeswari, G. V. B. A. Knowledge attitude and practice of yoga as an alternative therapy for treatment of occupational hazards among dentist In Chennai. NVEO-Natl. Volat. Essent. Oils J. NVEO. 6122–6135 (2021).

Boakye, H., Quartey, J., Baidoo, N. A. B. & Ahenkorah, J. Knowledge, attitude and practice of physiotherapists towards health promotion in Ghana. S Afr. J. Physiother. 74, 443 (2018).

Baskaran, S. & H. S. Evaluation of knowledge, attitude and practice of endodontic postgraduates towards preference of surgical vs non-surgical management of large periapical lesion-A survey. J. Pharm. Negat. Results (2022).

Yue, S., Zhang, J., Cao, M., Chen, B. & Knowledge Attitudes and practices of COVID-19 among urban and rural residents in china: A Cross-sectional study. J. Community Health. 46, 286–291 (2021).

McCormack, J. C., Chu, J. T. W., Marsh, S. & Bullen, C. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder in health, justice, and education professionals: A systematic review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 131, 104354 (2022).

El-Sallamy, R. M., Atlam, S. A., Kabbash, I., El-Fatah, S. A. & El-Flaky, A. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards ergonomics among undergraduates of faculty of dentistry, Tanta university, Egypt. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 25, 30793–30801 (2018).

Lau, L. L. et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of COVID-19 among income-poor households in the philippines: A cross-sectional study. J. Glob Health. 10, 011007 (2020).

Harapan, H. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding dengue virus infection among inhabitants of aceh, indonesia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 18, 96 (2018).

Passmore, H. M. et al. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD): knowledge, attitudes, experiences and practices of the Western Australian youth custodial workforce. Int. J. Law Psychiatry. 59, 44–52 (2018).

Sulistyawati, S. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, practices and information needs during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Risk Manag Healthc. Policy. 14, 163–175 (2021).

Wang, X. D., Feng, M. S. & Hu, Y. C. Establishment and finite element analysis of a Three-dimensional dynamic model of upper cervical spine instability. Orthop. Surg. 11, 500–509 (2019).

Pienimäki, T. Cold exposure and musculoskeletal disorders and diseases. A review. Int. J. Circumpolar Health. 61, 173–182 (2002).

Isogai, N. et al. Surgical treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy in the elderly: outcomes in patients aged 80 years or older. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 43, E1430–e1436 (2018).

Ma, H., Liu, T. & Liu, L. Modelling and analysis of fatigue physiological parameters of all tissues of football athletes under cervical vertebral stress based on Biomechanical analysis. Int. J. Nanotechnol. 19, 906–923 (2022).

Yin, M., Xu, C., Ma, J., Ye, J. & Mo, W. A bibliometric analysis and visualization of current research trends in the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Global Spine J. 11, 988–998 (2021).

Chung, S. & Jeong, Y. G. Effects of the craniocervical flexion and isometric neck exercise compared in patients with chronic neck pain: A randomized controlled trial. Physiother Theory Pract. 34, 916–925 (2018).

Stjernbrandt, A. & Hoftun Farbu, E. Occupational cold exposure is associated with neck pain, low back pain, and lumbar radiculopathy. Ergonomics 65, 1276–1285 (2022).

Atkins, P. A. & Voytas, D. F. Overcoming bottlenecks in plant gene editing. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 54, 79–84 (2020).

Chuang, C. H., Velott, D. L. & Weisman, C. S. Exploring knowledge and attitudes related to pregnancy and preconception health in women with chronic medical conditions. Matern Child. Health J. 14, 713–719 (2010).

Ango, U. M. et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of hand hygiene among healthcare providers in semi-urban communities of Sokoto state. Nigeria Int J. Trop. Dis. Health. 26, 1–9 (2017).

Ghezeljeh, T. N. & Soltandehghan, K. The effect of self-management education on the quality of life and severity of the disease in patients with severe psoriasis: A non-randomized clinical trial. Nurs. Pract. Today. 5, 243–255 (2018).

Mazzuoccolo, L. D. et al. WhatsApp: A Real-Time tool to reduce the knowledge gap and share the best clinical practices in psoriasis. Telemed J. E Health. 25, 294–300 (2019).

Vigier-Fretey, C. S. et al. Beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors of physical therapists towards differential diagnosis in chronic neck pain etiology. Hospitals 2, 7 (2025).

Tarimo, N. & Diener, I. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs on contributing factors among low back pain patients attending outpatient physiotherapy treatment in Malawi. S Afr. J. Physiother. 73, 395 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xudong Che, Wenming Xiu and Yang Qin carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. Ruitong Che, Xudong Che and Hong Zhang performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. Xudong Che Leijiang and Ruitong Che participated in acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical review committee statement

This work has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Associatio. This study was approved by Medical Ethics Committee of Dalian Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Che, R., Xiu, W., Qin, Y. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of cervical spondylosis in the general public. Sci Rep 15, 32870 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18501-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18501-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Perceived knowledge and attitude towards blended learning in pharmacology among medical students

Scientific Reports (2025)