Abstract

Previous studies have revealed that parental psychological control has a significant and lasting effect on increasing anxiety. However, few studies have examined the underlying mechanisms of this relationship from the perspective of positive psychology. The present study aims to explore the mediating role of positive youth development (PYD) and the moderating role of mindfulness in the relationship between parental psychological control and anxiety among Chinese adolescents. Totally 1,752 junior high school students completed questionnaires measuring their levels of perceived father’s/mother’s psychological control (FPC/MPC), anxiety, PYD, and mindfulness. Correlations among the variables were computed using Pearson’s r. Mediation and moderated mediation models were tested by using the PROCESS macro with the regression bootstrapping method. The results showed that: (1) FPC/MPC were positively associated with anxiety; (2) PYD partially mediated the FPC/MPC-anxiety association; and (3) both the FPC/MPC-PYD and FPC/MPC-anxiety relationships were moderated by mindfulness. From the above results, it could be inferred as below. Parents exercising less psychological control over their children in daily life may help reduce the risk of anxiety in adolescents. Cultivating positive youth development is crucial for adolescents’ mental health, as it may play a significant role in the relationship between parental psychological control and anxiety. Mindfulness may buffer the effects of parental psychological control in relation to positive youth development and anxiety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the criticism of rote learning and the implementation of the government’s “double reduction” policy in China, mental health issues among adolescents have become an increasingly significant concern in society in recent years. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, a global study involving 80,000 adolescents revealed that the prevalence of mental health problems, such as anxiety and obsessive–compulsive disorder, has doubled during the pandemic1. Factors such as parental expectations, academic pressure, and social stress contribute to varying degrees of anxiety in adolescents during this emotionally sensitive period. Numerous studies have identified adolescents as a high-risk group for anxiety2,3,4. Adolescents suffering from anxiety often experience excessive worry and fear, accompanied by a range of physical reactions, including palpitations, dizziness, and motor restlessness. Without intervention, these symptoms can persist and are likely to worsen over time. Anxiety not only has immediate negative effects on adolescents, such as reduced learning efficiency and psychological dysfunction5, but it can also lead to long-term consequences, including an increased risk of physical illnesses (such as gastric ulcers), decreased subjective well-being and self-efficacy, substance abuse, and other mental disorders (such as depression)6. Furthermore, anxiety is closely linked to adolescents’ interpersonal relationships, including parent–child relationships, peer relationships, and teacher-student relationships7.

This study focuses on anxiety among Chinese adolescents. Individuals with anxiety symptoms often experience frequent and prolonged negative emotions, which can lead to significant impairment in their daily lives. An in-depth examination of the factors influencing adolescent anxiety is essential for preventing anxiety symptoms and implementing tailored interventions.

Parental psychological control and adolescent anxiety

While genetic predispositions establish biological vulnerability, the operationalization of external factors—particularly maladaptive parenting practices—provides critical intervention targets for anxiety prevention. According to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory8, the onset and development of mental illness are significantly affected by negative relational systems, including the microsystem (e.g., poor family functioning), mesosystem (e.g., school maladjustment and poor peer relationships), exosystem (e.g., harsh parental workplace conditions), and macrosystem (e.g., a depressed culture and social environment). Moreover, parenting is the most fundamental and critical factor influencing individual development. Among various parenting styles, the one deeply rooted in Chinese family culture that profoundly impacts adolescents is passive parental psychological control. Psychological control refers to parental behaviors that manipulate children’s emotions through guilt induction, love withdrawal, and intrusive regulation9. This form of control restricts adolescent autonomy, posing challenges in identity formation and emotional regulation10. According to Self-Determination Theory (SDT), thwarting basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—leads to heightened anxiety and negative emotions11. Once adolescents’ behavior and decisions rely on parental control rather than authentic motivation, this psychological control can obstruct the fulfillment of their basic needs. This obstruction may hinder the development of autonomy and impair social and psychological functioning, ultimately resulting in anxiety12. Social Cognitive Theory suggests that individuals develop coping mechanisms through observation and social interactions, but excessive parental psychological control may lead to maladaptive responses such as avoidance or overdependence among adolescents13. Empirical studies indicate that adolescents experiencing high psychological control exhibit more negative automatic thoughts, increasing their anxiety levels14. Neuroscientific research further supports this view, showing abnormal activity in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex of individuals exposed to psychological control, impairing their emotional regulation capacity15. Additionally, Attachment Theory suggests that parental psychological control weakens the development of secure attachment, making adolescents more susceptible to anxiety when facing challenges16. In conclusion, the impact of parental psychological control on adolescent anxiety is multidimensional, encompassing autonomy frustration, emotional regulation difficulties, and insecure attachment.

Most previous studies have explored the impact of parental psychological control on adolescent anxiety, focusing on adolescents’ perceptions of overall parental psychological control. However, there are significant differences in the psychological control exerted by fathers and mothers in their upbringing of children. Existing research consistently indicates that mothers demonstrate a higher level of psychological control over their children than fathers17,18. Moreover, the psychological control exerted by fathers and mothers has distinct effects on children’s development. For example, father’s psychological control can significantly and positively predict depression in primary school students exhibiting symptoms of Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), whereas mother’s psychological control does not have the same predictive effect19. Using primary school students as research participants, the study found that mother’s psychological control positively predicts children’s anxiety, whereas father’s psychological control does not20. A cross-sectional study found that both father’s and mother’s psychological control were significantly positively correlated with trait anxiety among college students21. In addition to exerting varying degrees of influence on adolescent anxiety, the psychological control exercised by fathers and mothers follows distinct pathways. According to gender socialization theory22, fathers in traditional Chinese families typically assume more “instrumental roles”, and supervision, while mothers take on "emotional roles”, this differentiation in roles results in mother’s psychological control being primarily expressed through emotional withdrawal, which can lead to emotional anxiety. In contrast, father’s psychological control is often manifested through authoritative suppression, contributing to achievement anxiety23. Therefore, in conjunction with the purpose of this study, when exploring the impact path, exploring the role of father and mother psychological control in the path separately may be more helpful for precise intervention in adolescent anxiety.

Positive youth development as mediator

Previous research on adolescence has often concentrated on issues that may contribute to negative self-identification among youth. In contrast, the Positive Youth Development (PYD) framework, rooted in positive psychology and Developmental Systems Theory, aims to guide research on adolescents and young adults by shifting the focus from problems to the developmental potential and resources of these individuals24. Recently, the PYD model that has garnered the most empirical support and is widely utilized internationally is the 5Cs model of PYD proposed by Lerner et al. This model encompasses five key components: Competence, Confidence, Connection, Character, and Caring. Additionally, a 77-item Positive Youth Development Student Questionnaire (PYDSQ) was developed based on the 5Cs model25. However, the previous Positive Youth Development Questionnaires include a wide range of items and may not be applicable in certain situations where time or environmental constraints exist, such as in daily use and follow-up studies. Consequently, American researchers developed a 17-item minimalist version of the 5Cs Positive Youth Development Very Short Form (PYD-VSF) based on the original 77-item PYDSQ26, its validity has been confirmed in a longitudinal study of American adolescents27. Chinese scholars Huang et al. also validated the applicability of a minimalist version of the Positive Youth Development Scale among adolescents at various educational stages24.

According to developmental systems theory28, positive youth development (PYD) results from the dynamic interaction between individuals and their environment. When combined with the three basic psychological needs outlined in self-determination theory—autonomy, competence, and relatedness29—parental psychological control can impede the development of the 5Cs traits in adolescents through several pathways. First, by undermining their autonomy and suppressing self-determination, parental control negatively impacts the development of adolescents’ competence and confidence. Additionally, through the use of conditional love, it undermines adolescents’ need for relatedness, thereby affecting their capacity for caring and connection. Excessive parental psychological control can also obstruct the development of adolescents’ psychological functions30, further hindering their positive development. This developmental stunting can leave adolescents without the resources necessary to cope with anxiety31, creating a mechanism of “developmental debt accumulation”.

The existing research has demonstrated that family functioning is significantly related to psychological resilience32 and emotional intelligence33. There is a significant negative correlation between parental psychological control and adolescents’ psychological resilience34, self-efficacy35, and self-compassion36. Based on this information, this study hypothesizes that parental psychological control negatively predicts positive youth development.

Furthermore, several studies have shown that positive youth development characteristics can significantly and negatively predict adolescent anxiety. These characteristics include social support37, gratitude38, empathy39, and self-concept40. It is evident that various dimensions of positive youth development are closely linked to adolescent anxiety. Some studies have also found that specific aspects of positive youth development, such as positive beliefs41, emotional skills39, mental resilience42 and attributional style43, mediate the relationship between family factors—such as parental psychological control, harsh parenting, and family functioning—and adolescent anxiety. These studies indicate that parental psychological control significantly impacts adolescents’ anxiety by influencing specific dimensions of positive youth development. However, most existing research focuses on one or two dimensions as mediators, with few studies integrating multiple dimensions for a comprehensive analysis. A holistic view of positive youth development may better reflect the current realities faced by adolescents. Therefore, this study hypothesizes that positive youth development may serve as a mediating factor in the relationship between parental psychological control and adolescent anxiety, with the goal of providing a comprehensive theoretical framework for future prevention and intervention programs.

Mindfulness as moderator

Although parental psychological control can negatively affect adolescents, individual differences may influence this impact. The Individual-Context Relations Theory posits that the same environmental factors can have varying effects on different individuals, and that the interaction between personal traits and the environment ultimately shapes individual development outcomes44. Moreover, the Relational-Developmental-Systems Model aligns with the perspective of interaction between individuals and their environments. This theory posits that personal strengths and environmental resources positively influence adolescent development, which in turn impacts individual contributions as well as risk and problem behaviors25,45.

Numerous studies have shown that mindfulness, as a positive psychological trait, can serve as a protective factor for individual development. Mindfulness is defined as a state of intentional and non-judgmental awareness of the present moment46,47. Mindfulness can also enhance the mental health of adolescents and alleviate their negative emotional states48. Additionally, mindfulness can mitigate the negative impact of detrimental factors on mental health. Based on the stress buffering hypothesis49, mindfulness mitigates the effects of stress through three primary mechanisms. First, the cognitive dissociation mechanism of mindfulness can reduce over-identification with negative experiences50. Second, according to the emotion regulation mechanism, high levels of mindfulness can enhance the prefrontal cortex’s regulation of the amygdala51. Finally, through the metacognitive monitoring mechanism, a state of mindfulness can promote the selection of adaptive coping strategies52. For example, some studies have found that mindfulness can mitigate the effects of psychological distress on unhealthy eating behaviors53; alleviate the impact of bullying on psychological resilience and depression54; and reduce the effect of online social exclusion on adolescents55. Therefore, this study speculates that mindfulness may play a moderating role in the relationship between parental psychological control and adolescent anxiety, and it may moderate the first half of the path through which parental psychological control affects adolescent anxiety through positive development.

The present study

Despite the extensive research on the relationship between parental psychological control and anxiety, several gaps remain. First, few studies have examined the underlying mechanisms of this relationship from the perspective of positive psychology. From the standpoint of promoting positive youth development, exploring the role of positive factors is more beneficial for adolescent growth. Second, while some individual positive factors have been identified that help alleviate parental psychological control in adolescents, there is a lack of research on the impact of overall positive qualities (e.g., Positive Youth Development) on parental psychological control and adolescents’ anxiety. Investigating the overall context may better reflect the current state of positive development among adolescents. Third, only a limited number of studies have explored the impacts and differences between fathers’ and mothers’ psychological control on anxiety in Chinese adolescents, particularly those attending junior middle schools. These adolescents may face significant challenges during puberty due to the substantial physical and mental changes they experience, as well as the major transition from primary to middle school, which can impose considerable academic and interpersonal pressure.

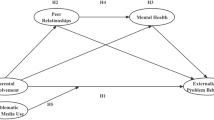

In view of the above, this study hypothesized that positive youth development would play a mediating role in both FPC-anxiety and MPC-anxiety (hypothesis 1&2), and mindfulness would play a moderating role in both FPC-PYD and FPC-anxiety (hypothesis 3&4), as well as the relationship between MPC-PYD and MPC-anxiety (hypothesis 5&6). The proposed moderated mediation model is presented in Fig. 1.

Methods

Participants

Randomized cluster sampling was employed to collect data in October 2023 from three public middle schools in Guangdong Province, China. This study selected junior middle school students in Grades 7 and 8 as participants. A total of 1,770 students volunteered to participate in the study. After excluding questionnaires with consistent responses, such as selecting the same option for more than ten consecutive questions or exhibiting a zigzag pattern (e.g., 1–2-1–2), as well as those with missing values for key variables exceeding 30% (in accordance with Enders’ 2022 data processing standards)56, using multiple imputation for small amount of missing data, a total of 1752 qualified respondents remained. We conducted comprehensive power analyses to ensure adequate sensitivity. Based on the mediation effect sample size table developed by Fritz and MacKinnon57, a sample size of 442 was necessary to detect a medium effect size (κ2 = 0.13) at an alpha level of 0.05 and a beta level of 0.2. Moderation effect analysis was conducted using GPower 3.1 (with three predictors and an f2 of 0.02), which indicated that a sample size of 788 was required to achieve 80% power58. Our final sample (N = 1,752) provides 95% power to detect indirect effects as small as 0.015 (using PROCESS v4.3), offers 90% sensitivity for interaction effects with f2 ≥ 0.01, and maintains type I error control at α < 0.05 through the Westfall-Young permutation59. The participants comprised 926 (52.85%) male students and 826 (47.15%) female students, aged between 11 and 16 years old (M = 12.78, SD = 0.53). Among the participants surveyed, 17.8% are only children, while 82.2% are not. Additionally, 83.1% reside in urban areas, compared to 16.9% who live in rural regions. A significant 90.5% have married parents, with 6.3% experiencing divorce, 2.5% having remarried parents, and 0.7% living with a widowed parent. Furthermore, 52.1% come from two-parent families, while 5.3% are from single-parent households, 1.9% belong to reconstituted families, and 40.7% are part of large families consisting of three generations or more. In terms of upbringing, 70.2% were primarily raised by their parents, 18.3% by their grandparents, and 11.5% by other relatives. Lastly, 50.1% of respondents feel that their family environment is harmonious and peaceful, while 46.4% report occasional quarrels, and 3.5% experience frequent conflicts.

Procedure

The study was approved by the relevant school boards, principals, and teachers as well as the Human Research Committee of University (PSY-2023–077). Informed written consent was obtained from all study participants and their guardians. Data collection was conducted during the regular teaching hours of the participating schools. Each class, consisting of approximately 40 to 50 students, was tested independently in their own classrooms. All students participated voluntarily. An informed consent statement was read aloud before the questionnaire was distributed: "This survey is completely voluntary. You may stop answering or leave the classroom at any time without affecting your rights and interests in school." This study utilized a standardized training manual to ensure that all research assistants received uniform training. The manual emphasized the importance of consistent guidelines and assessment procedures while addressing some key points that should be considered during the distribution of the assessment. Participants received the same verbal and written instructions from the trained research assistant and were given ample time to complete the questionnaires. They were assured of the strict confidentiality of the collected data, with access to the completed questionnaires restricted to research personnel only.

Measures

This study utilized the Depression-Anxiety-Stress Scale (DASS-21) anxiety subscale to measure state anxiety60, which evaluates the acute anxiety symptoms experienced by individuals over the past week (e.g., "I feel short of breath" and "I experience body tremors"), reflecting situational emotional responses. In contrast to trait anxiety scales, such as the STAI-T, the DASS-21 does not assess stable anxiety tendencies60. The scale has been rigorously validated across cultures in Chinese adolescents and demonstrates strong reliability and validity61. The anxiety subscale is a 7-item scale. All items were rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 ("Not at all") to 3 (“Almost always”). Higher total scores reflect greater anxiety severity. The Chinese version of this subscale demonstrated good reliability in our sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.85).

Parental psychological control was assessed using the Chinese version of the Parental Psychological Control Scale, which was originally compiled by the Hong Kong scholar Shek62. It has successfully undergone cross-cultural testing in mainland China and demonstrates strong reliability and validity.63. The scale has 10 items and is used to measure the degree of parental psychological control perceived by adolescents (e.g., my father/mother often wants to change my thoughts or feelings about things.). All items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = “Very inconsistent”, 5 = “Very consistent”). The level of perceived parental psychological control is reflected by a total score of the 10 items, higher scores indicate greater levels of perceived parental psychological control. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the father’s psychological control scale in this study was 0.89, the mother’s psychological control scale in this study was 0.90.

This study utilizes the Chinese version of the Positive Youth Development-Very Short Form (PYD-VSF-C), revised by Huang et al.24. This version has been cross-culturally adapted from the original 17-item scale developed by Geldhof (2013)26. Following the International Testing Council (ITC) cross-cultural adaptation guidelines64, the research team conducted a two-stage optimization process24. In the first stage, the 12th item ("I am good at making plans for my future") was removed from the original scale. Pre-experimental findings indicated that this item exhibited cross-cultural ambiguity within the Chinese adolescent sample, as their understanding of “future planning” tends to emphasize academic planning over holistic development. Additionally, this item demonstrated low factor loading (λ = 0.32, below the 0.40 threshold) and a high correlation with the academic stress scale (r = 0.61), which could introduce common method bias. In the second stage, model optimization was performed. The resulting 16-item version exhibited improved fit indices (ΔCFI = + 0.03, ΔRMSEA = -0.02) compared to the original version, while preserving the integrity of the theoretical structure (5-factor model χ2/df = 2.11). The scale consists of 16 items within 5 domains: Competence (three items), Confidence (three items), Character (three items), Caring (three items), and Connection (four items). All items are rated on a 5-point Likert type scale (1 = “Very inconsistent”, 5 = “Very consistent”). Positive youth development is expressed by mean value of total scores of all five subscales with higher scores indicating higher level of positive development. The scale demonstrated good internal reliability (α = 0.82) and good fit indices in confirmatory factor analysis (CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.04) in this study.

The Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM) was used to assess mindfulness, which originally developed by Greco et.al65. The Chinese version has undergone cross-cultural validation and demonstrates strong reliability and validity66. The scale consists of 10 items. All items are rated on a 5-point Likert type scale (0 = “Never”, 4 = “Always”). The level of mindfulness is reflected by a total score of the 10 items, for all items are reverse scored, a higher total score indicates a lower level of mindfulness. In order to facilitate understanding of data presentation, all items in this study will be reverse scored. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.80.

All the scales and scores administered in the present study are publicly available and widely used in academic research, thus, no special permission was required.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 25). Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for father’s psychological control, mother’s psychological control, positive youth development, mindfulness, and anxiety. Correlations were computed using Pearson’s r. Mediation and moderated mediation models were using PROCESS67 with 5000-iteration bootstrapping to compute standardized Betas with 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals. Confidence intervals not containing zero are statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 25 and PROCESS v4.3 (Model 4 for mediation; Model 59 for moderated mediation) with the following specifications: (1) Mediation Analysis: father’s/mother’s psychological control (X) → Positive Youth Development (PYD, M) → Anxiety (Y) relationships were examined using 5000 bias-corrected bootstrap samples. Standardized indirect effects were considered significant if 95% CIs excluded zero, and proportion mediated (PM) was calculated per Lachowicz68; (2) Moderated Mediation: Mindfulness was tested as a moderator among the pathway of FPC/MPC-anxiety and FPC/MPC-PYD using mean-centered variables. Johnson-Neyman technique identified regions of significance69, with Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons70; (3) Post-hoc Analyses: Conditional indirect effects were plotted at ± 1SD mindfulness levels, supported by 5000-iteration bootstrapping67, to explicate the moderating effect of mindfulness.

Results

Common method biases

Harman’s single-factor method71 was used to conduct exploratory factor analysis on all variables. The results indicated that there were 10 factors with characteristic roots greater than 1, with the first factor explaining 21.04% of the variance, which is below the critical threshold of 40%. Consequently, there was no significant common method bias in this study.

Descriptive statistics and correlations analysis

The results of the descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) and correlation analysis for the major variables are presented in Table 1. Significant bivariate correlations emerged among all study variables: father’s psychological control, mother’s psychological control, anxiety symptoms, positive youth development (PYD), and mindfulness. Father’s psychological control (FPC) and mother’s psychological control (MPC) were positively associated with anxiety and negatively associated with PYD and mindfulness. Conversely, PYD was negatively correlated with anxiety and positively correlated with mindfulness. Additionally, mindfulness was negatively correlated with anxiety. Gender was positively associated with MPC and anxiety, while it was negatively associated with PYD and mindfulness.

Mediation model (FPC)

As demonstrated in Table 2 and Fig. 2a, FPC was positively associated with anxiety in the absence of the mediator (β = 0.31, p < 0.001). Additionally, FPC was negatively associated with PYD (β = -0.30, p < 0.001). When FPC was controlled, PYD was negatively correlated with anxiety (β = -0.17, p < 0.001). Subsequently, when PYD was included, the positive association between FPC and anxiety remained significant (β = 0.25, p < 0.001). Finally, as shown in Table 3, the indirect effect of PYD was 0.06, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.03, 0.07], indicating that PYD partially mediated the association between FPC and anxiety, thereby supporting Hypothesis 1. By calculating the effect ratio using the indirect effect divided by the total effect, the mediation effect accounted for 19.35% of the total effect of the association between FPC and anxiety.

Mediation model (MPC)

As demonstrated in Table2 and Fig. 2b, MPC was positively associated with anxiety in the absence of the mediator (β = 0.36, p < 0.001). In addition, MPC was negatively associated with PYD (β = -0.23, p < 0.001). When MPC was controlled for, PYD was negatively correlated with anxiety (β = -0.17, p < 0.001). Next, PYD was included, and the positive association between MPC and anxiety was still significant (β = 0.32, p < 0.001). Finally, as shown in Table3, the indirect effect of PYD was 0.04, and its 95% confidence interval was [0.03, 0.06], suggesting that PYD partially mediated the association between MPC and anxiety, thus the hypothesis 2 was supported. Using indirect effect divided by total effect to calculate the effect ratio, the mediation effect accounted for 11.11% of the total effect of the association between MPC and anxiety.

Testing for moderated mediation model

As described in Fig. 1, we hypothesized that PYD would mediate the direct and indirect association between FPC/MPC and anxiety.

Table 4 illustrated the results of the conditional process analysis. As can be seen from the dependent variable model that predicts PYD, FPC/MPC was negatively associated with PYD (β1 = −0.28, p < 0.001; β1 = −0.21, p < 0.001), and the interaction between FPC/MPC and mindfulness was negatively associated with PYD (β2 = −0.07, p < 0.01; β2 = −0.06, p < 0.01). It indicated that mindfulness moderated the relationship between FPC/MPC and PYD, the hypothesis 3&5 was supported. In addition, FPC/MPC was positively associated with anxiety (β1 = 0.11, p < 0.001; β1 = 0.17, p < 0.001), and the interaction between FPC/MPC and mindfulness was negatively associated with anxiety (β2 = −0.06, p < 0.001; β2 = −0.16, p < 0.01). Namely, mindfulness moderated the relationship between FPC/MPC and anxiety, such that the hypothesis 4&6 was supported.

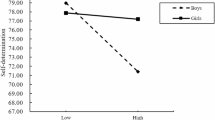

To explicate the moderating effect of mindfulness, the plot of relationship between FPC/MPC and PYD at two levels of mindfulness (1SD below the mean and 1SD above the mean) was described in Fig. 3a and b. For adolescents with low mindfulness (1SD below the mean), there was a strong negatively correlation (β2 = −0.34, p < 0.001; β2 = −0.27, p < 0.001) between FPC/MPC and PYD. For adolescents with high mindfulness (1SD above the mean), the association between FPC/MPC and PYD was still significant and negative but weaker (β2 = −0.21, p < 0.001; β2 = −0.15, p < 0.001).

Plot of relationship between FPC/MPC and PYD as well as FPC/MPC and anxiety at different levels of mindfulness. (a) plot of the relationship between FPC and PYD at diffferent levels of mindfulness, (b) Plot of the relationship between MPC and PYD at different levels of mindfulness, (c) Plot of the relationship between FPC and anxiety at different levels of mindfulness. (d) Plot of the relationship between MPC and anxiety at different levels of mindfulness. Note. FPC = father’s psychological control, MPC = mother’s psychological control, PYD = positive youth development.

In addition, the plot of relationship between FPC/MPC and anxiety at two levels of mindfulness (1SD below the mean and 1SD above the mean) was displayed in Fig. 3c and d. As can be seen from Fig. 3d, for adolescents with low mindfulness (1SD below the mean), the positive association between MPC and anxiety was stronger than adolescents with high mindfulness (1SD above the mean) (β2 = 0.23 vs. β2 = 0.11). There was a strong positively association between FPC and anxiety for low-mindfulness adolescents (β2 = −0.17, p < 0.001), however, the correlation between FPC and anxiety was not significant among adolescents with high mindfulness (β2 = −0.05, p > 0.05).

Discussion

In the present study, we proposed a moderated mediation model to examine the relationship between parental psychological control, anxiety, positive youth development, and mindfulness. Our findings have both theoretical and clinical implications for the prevention and treatment of anxiety among adolescents who perceive high levels of psychological control from either their father or mother.

This study found that positive youth development partially mediates the relationship between parental psychological control (from both fathers and mothers) and adolescent anxiety. According to self-determination theory, parental psychological control undermines adolescents’ sense of autonomy and diminishes their intrinsic motivation during self-development. This, in turn, negatively impacts their positive development and contributes to increased anxiety72. From a cognitive perspective, adolescents who are restrained and controlled by highly authoritarian parents during their formative years may experience negative impacts on their self-perception and understanding of their environment. This can hinder their ability to engage in positive social interactions and impede their cognitive development, ultimately affecting their emotions and behaviors73. The emotion regulation theory posits that in a family environment characterized by high psychological control, adolescents may develop a distorted sense of control and a misperception of reality. This can hinder their ability to respond effectively to developmental challenges, ultimately leading to anxiety74,75. From a developmental perspective, junior high school students are at a stage characterized by self-identity exploration and role confusion. Parental psychological control can hinder their ability to explore their identities and establish a stable sense of self, which may prevent them from developing a positive self-perception and contribute to increased anxiety76. All of the above indicates that parental psychological control can lead to the emergence and development of anxiety by negatively impacting the positive development of adolescents. However, adolescence is the most malleable period of human development45, protection for adolescents against parental psychological control, as well as interventions aimed at promoting positive development among adolescents in high-control families, are equally important for their mental health.

On the other hand, this study found that mindfulness moderates the direct influence of father’s/mother’s psychological control on adolescent anxiety through positive youth development. Specifically, the direct effect of mother’s psychological control on adolescent anxiety is stronger among adolescents with low levels of mindfulness. As mindfulness levels increase, the negative predictive effect of mother’s psychological control on adolescent anxiety shows a significant downward trend. The role of mindfulness in the relationship between father’s psychological control and adolescent anxiety is somewhat different. Father’s psychological control does not lead to increased anxiety in adolescents with high levels of mindfulness. This suggests that higher levels of mindfulness can effectively buffer the negative impact of father’s psychological control on adolescent anxiety. The reason may be that mothers have more mental and emotional interactions and connections with their children than fathers do in daily life. Mothers are often more inclined to provide emotional support and discipline to their children, both psychologically and emotionally. For example, Chen and Cheng17 found that mothers exert a higher level of psychological control over primary school children compared to fathers. Our study also suggests that mother’s psychological control has a more significant impact on adolescent anxiety than father’s control. Therefore, fostering positive personal traits, such as mindfulness, may help mitigate the effects of father’s psychological control. In contrast, to alleviate the influence of mother’s psychological control, additional support may be necessary, including maternal awareness, peer support, and psychological counseling.

Moreover, this study found that mindfulness moderates the impact of father’s or mother’s psychological control on positive youth development. Specifically, higher levels of mindfulness are associated with a reduced negative impact of father’s/mother’s psychological control on the positive development of adolescents. This suggests that mindfulness may serve as a psychological resource that can buffer against the adverse effects of inadequate parenting. These findings align with the results of previous studies53,77,78. This result may be explained by several factors. First, mindfulness offers a non-judgmental and accepting approach for individuals to engage with their current experiences, which can help reduce rumination79. Therefore, adolescents with high levels of mindfulness may not be significantly affected by the negative consequences of a poor family environment for extended periods. Additionally, mindfulness enhances coping skills80. Adolescents with high levels of mindfulness are better equipped to cope with negative environmental influences, such as parental psychological control and poor parent–child relationships. This enhanced mindfulness allows them to continuously improve their adaptability81 and, in turn, reduce the risk of experiencing negative emotions, such as anxiety. Third, mindfulness can enhance individual psychological resources by improving psychological resilience, self-efficacy, and self-esteem82,83, which are crucial for the positive development of individuals84. Research indicates that the greater the psychological resources an individual possesses, the more effectively they can cope with negative influences from the external environment85. Hence, the negative impact of parental psychological control on anxiety, as mediated by positive youth development, may be mitigated, as adolescents with high levels of mindfulness possess greater psychological resources. This study highlights the protective effect of mindfulness on both physical and mental health.

Implications

This study systematically elucidates the mechanism by which parental psychological control influences adolescent anxiety and highlights the protective role of mindfulness through the construction of a moderated mediation model. At the theoretical level, this research is the first to integrate Developmental Systems Theory and the Stress-Buffering Model, proposing a dynamic balance framework of “family risk-development resources”. The findings indicate that parental psychological control indirectly exacerbates anxiety by undermining the 5Cs traits (Competence, Confidence, etc.) that are essential for positive development. This supports the core hypothesis of self-determination theory, which posits that the obstruction of basic psychological needs leads to developmental debt29. Additionally, the study expands the explanatory scope of ecological systems theory regarding micro-system mechanisms, demonstrating that father’s and mother’s psychological control function as independent risk factors with differentiated transmission pathways. The moderating effect of mindfulness exhibits a "dose–response" gradient: low levels of mindfulness can only mitigate the negative impact of father’s psychological control on adolescents, while high levels of mindfulness can completely block the pathway through which father’s psychological control affects adolescent anxiety. In contrast, mother’s psychological control does not exhibit this blocking effect, instead, mindfulness can only serve to buffer its impact. These findings validate the theoretical premise of conservation of resources theory86, which asserts that the accumulation of psychological resources has a nonlinear protective effect, and provide critical mechanistic evidence for the individual-environment interaction model of developmental contextualism45. In terms of practical application, this study proposes a three-tier intervention roadmap based on its findings. First, leveraging the "complete buffering effect" of mindfulness, a school-based mindfulness training program can be implemented to address fathers’ psychological control, enhancing core skills in emotion regulation through an 8-week course87. Second, a "joint intervention strategy" should be employed to target mothers’ psychological control, leading to the creation of a Maternal Mindfulness-Based Parenting Program that integrates cognitive dissociation training with the enhancement of parent–child communication skills88. Finally, a Positive Youth Development (PYD) promotion system for home-school collaboration should be established, aimed at bolstering adolescents’ psychological resilience through strengths-based interventions, such as the VIA character strengths assessment89. At the policy level, it is recommended to incorporate mindfulness literacy assessments and PYD development files into mental health services for primary and secondary schools.

Limitations and directions for future research

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the results of this study. Firstly, the current research employed a cross-sectional design, which does not fully establish causal relationships between variables or elucidate the mechanisms of mediation. Longitudinal studies are necessary to gain a deeper understanding of the relationships among these variables. Secondly, this study only considered gender and age as control variables. Future research should incorporate additional control variables, such as socioeconomic status, to provide a more comprehensive analysis. Theoretically, family socioeconomic status exacerbates parenting pressure through mechanisms of resource deprivation, such as inadequate investment in education and low community safety. This, in turn, increases psychological control90. Empirical evidence indicates that the incidence of parental psychological control in low-SES groups is significantly higher than in middle- and high-SES groups91. Therefore, future research should systematically measure multidimensional indicators of SES, including family income, parental education, and occupational prestige. Thirdly, although the sample size of this study is relatively large, all participants are from Guangdong Province, China, which limits the representativeness of the sample. It is necessary to extend the survey to a national sample in future studies. Furthermore, the association between FPC/MPC and anxiety may differ between adolescent boys and girls. Examining the factors that play varying roles in the underlying mechanisms will further enrich empirical research and provide a foundation for understanding gender differences in this relationship, as well as offer new insights for designing targeted intervention programs. For instance, boys may be more sensitive to the threat of autonomy from father’s psychological control due to an enhanced stress response mediated by testosterone levels92. In contrast, girls may exhibit unique vulnerability pathways stemming from the internalization of mother’s emotional withdrawal during gender socialization93 and the reinforcement of the cultural script of “filial piety identity”94. In the future, functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) technology should be utilized to explore gender-specific neural pathways. Finally, this study utilized the DASS-21 anxiety subscale, which primarily measures state anxiety and may not adequately reflect the stable trait anxiety characteristics of adolescents. Future research could integrate physiological indicators, such as cortisol levels, and employ longitudinal designs to differentiate between situational anxiety and long-term anxiety tendencies.

Conclusion

This study systematically elucidates the mechanisms of parental psychological control and anxiety in Chinese adolescents by constructing a dynamic model of "family risk-developmental resources". (1) Father’s and mother’s psychological control indirectly exacerbates anxiety by undermining the 5Cs traits of positive youth development (PYD), thereby supporting the basic needs blockage hypothesis of self-determination theory; (2) Mindfulness can mitigate the negative impact of father’s and mother’s psychological control on adolescents’ positive development; (3) Mindfulness exhibits a differentiated buffering effect on mother’s and mother’s psychological control: high levels of mindfulness can completely block the anxiety transmission pathway associated with father’s psychological control, while it only weakens the intensity of the effect related to mother’s psychological control.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the first author (Mingshi Du, dms0217@163.com) on reasonable request.

References

de Figueiredo, C. S. et al. Covid-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Progr Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 106, 110171 (2021).

Hu, M. et al. Investigation on the current status of anxiety among middle school students in Hunan Province and analysis of related factors. Chin J Clin Psychol. 06, 592–594 (2007).

Xie, Z., Hong, W., Zhao, N. & Yin, J. The mediating role of social support in the relationship between biological desire motivation and anxiety in high school students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 19, 528–530 (2011).

Costello, E. J., Foley, D. L. & Angold, A. 10-year research update review: The epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: II. Developmental epidemiology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 45, 8–25 (2006).

Last, C. G., Hansen, C. & Franco, N. Anxious children in adulthood: A prospective study of Adjustment. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 36, 645–652 (1997).

Woodward, L. J. & Fergusson, D. M. Life course outcomes of young people with anxiety disorders in adolescence. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 40, 1086–1093 (2001).

Li, Y., Zhang, S. & Wang, J. Model construction of middle school students’ trait anxiety and its influencing factors. Acta Psychol. Sin. 03, 289–294 (2002).

Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory Annals of child development: Theories of child development. (1989).

Barber, B. K. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 67, 3296–3319 (1996).

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M. & Luyten, P. Toward a domain-specific approach to the study of parental psychological control: Distinguishing between dependency-oriented and achievement-oriented psychological control. J. Pers. 78, 217–256 (2010).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. The, “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268 (2000).

Grolnick, W. S. & Pomerantz, E. M. Issues and challenges in studying parental control: Toward a new conceptualization. Child Dev Perspect. 3, 165–170 (2009).

Bandura, A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory (Prentice-Hall, Hoboken, 1986).

Kins, E., Beyers, W., Soenens, B. & Vansteenkiste, M. When the separation-individuation process goes awry: Distinguishing between dysfunctional dependence and dysfunctional independence. J. Adolesc. 36, 1025–1037 (2013).

Whittle, S., Yap, M. B., Sheeber, L. & Allen, N. B. Family influences on adolescent depressive symptoms: The role of emotion regulation. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 45, 698–710 (2014).

Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books. (1969).

Chen, H.-Y. & Cheng, C.-L. Parental psychological control and children’s relational aggression: Examining the roles of gender and normative beliefs about relational aggression. J. Psychol. 154, 159–175 (2019).

Liu, Y. & Chen, J. The nonlinear relationship between parental psychological control and adolescent risk-taking behavior: the moderating role of self-esteem. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 35, 401–410 (2019).

Lin, X. et al. The relationship between parental psychological control and depression and aggressive behavior in children with ODD symptoms. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 30, 635–645 (2014).

Xu, F., Cui, W. & Lawrence, P. J. The intergenerational transmission of anxiety in a Chinese population: The mediating effect of parental control. J. Child Fam. Stud. 29, 1669–1678 (2019).

Seibel, F. L. & Johnson, W. B. Parental control, trait anxiety, and satisfaction with life in college students. Psychol. Rep. 88, 473–480 (2001).

Bussey, K. & Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychol. Rev. 106, 676–713 (1999).

Cheung, R. Y. M. & Wang, I. Y. Parents’ gender role attitudes and child adjustment: The mediating role of parental involvement. Sex Roles 89, 425–441 (2023).

Huang, L., Liang, K., Chen, S., Kang, W. & Chi, X. Validity and reliability testing of the Chinese version of the minimalist positive youth development scale. Chin J Mental Health. 36, 445–450 (2022).

Lerner, R. M. Developmental science, developmental systems, and contemporary theories of human development. Handbook of Child Psychology. (2007).

Geldhof, G. J. et al. Creation of short and very short measures of the five cs of positive youth development. J. Res. Adolesc. 24, 163–176 (2013).

Geldhof, G. J. et al. Longitudinal analysis of a very short measure of positive youth development. J Youth Adolesc. 43, 933–949 (2014).

Lerner, R. M. et al. Positive youth development in 2020: Theory, research, programs, and the promotion of social justice. J. Res. Adolesc. 31, 1114–1134 (2021).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness (Guilford Publications, New York, 2017).

Flamant, N., Haerens, L., Vansteenkiste, M. & Soenens, B. A daily examination of the moderating role of adolescents’ coping in associations between psychologically controlling parenting and adolescents’ maladjustment. J. Youth Adolesc. 51, 2035–2049 (2022).

Geldhof, G. J., Bowers, E. P. & Lerner, R. M. Thriving in context: Findings from the 4-H study of positive youth development. J Youth Dev. 17, 15–34 (2022).

Ng, Y. Y. & Wan Sulaiman, W. S. Resilience as mediator in the relationship between family functioning and depression among adolescents from single parent families. Akademika. 87, 111–122 (2017).

Cigala, A., Venturelli, E. & Fruggeri, L. Family functioning in microtransition and socio-emotional competence in preschoolers. Early Child Dev. Care 184, 553–570 (2013).

Li, R. The relationship between parental psychological control and adolescent depression: a study on the mediating role and intervention of psychological flexibility (Master’s thesis, West China Normal University) (2023).

Yan X. The impact of parental psychological control on personal growth initiative: the mediating role of self-efficacy and the moderating role of self-compassion (Master’s thesis, Shenyang Normal University) (2022).

Lai, L. The relationship between parental control and depression among junior high school students: the. Mediating role of self-compassion and the moderating role of friendship quality (Master’s thesis, Guangxi University for Nationalities) (2023).

Wang, L., Jia, J., Lei, Q. & Jianh, Q. The impact of family function on the anxiety level of junior high school students whose parents migrate to work: Understanding the mediating role of social support. Mod Prim Second Educ. 01, 69–74 (2024).

Tang Y. The impact of mindfulness on the mental health of junior high school students: the mediating role of gratitude (Master’s thesis, Nanning Normal University) (2023).

Peng, Y. et al. The impact of family function on adolescents’ internalizing problem behaviors: The multiple mediating effects of empathy and emotional ability. J Sichuan Univ (Med Ed). 55, 146–152 (2024).

Li, X. The relationship between parental harsh discipline behavior and adolescent internalizing problems: a moderated mediation model (Master’s thesis, Qingdao University) (2023).

Zhou, P. & Liu, Y. The impact of rough parenting on adolescent anxiety: A moderated mediation model. Chin J Health Psychol. 02, 290–295 (2024).

Zhou H. The relationship between parental psychological control and social anxiety among high school. Students: the chain mediating role of parent-child relationship and positive psychological capital (Master’s thesis, Hebei University) (2023).

Schleider, J. L., Vélez, C. E., Krause, E. D. & Gillham, J. Perceived psychological control and anxiety in early adolescents: The mediating role of attributional style. Cogn. Ther. Res. 38, 71–81 (2013).

Lerner, R. M. Diversity in individual-context relations as the basis for positive development across the life span: A developmental systems perspective for theory, research, and application. Special Issue: Risk and Resilience in Human Development, 327–346 (2018).

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., P. Bowers, E., & John Geldhof, G. Positive youth development and relational‐developmental‐systems. Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science. 1–45 (2015).

Bishop, S. R. et al. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 11, 230–241 (2004).

Brown, K. W. & Ryan, R. M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84, 822–848 (2003).

Chen, S. et al. Revision and reliability and validity test of the mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS). Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 20, 148–151 (2012).

Cohen, S. & Wills, T. A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310–357 (1985).

Tsai, N. et al. Dispositional mindfulness: Dissociable affective and cognitive processes. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 30, 123–134 (2023).

Tang, Y.-Y., Hölzel, B. K. & Posner, M. I. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 213–225 (2022).

Ortner, C. N. M. & Zelazo, P. D. Mindfulness meditation and reduced emotional interference on a cognitive task. Motiv. Emot. 31, 271–283 (2007).

Pidgeon, A., Lacota, K. & Champion, J. The moderating effects of mindfulness on psychological distress and emotional eating behaviour. Aust. Psychol. 48, 262–269 (2013).

Zhou, Z.-K., Liu, Q.-Q., Niu, G.-F., Sun, X.-J. & Fan, C.-Y. Bullying victimization and depression in Chinese children: A moderated mediation model of resilience and mindfulness. Personal Individ. Differ. 104, 137–142 (2017).

Lei, Y. et al. The impact of online social exclusion on depression: A moderated mediating effect model. Psychol. Sci. 41, 98–104 (2018).

Enders, C. K. Applied missing data analysis 2nd edn. (Guilford Press, New York, 2022).

Fritz, M. S. & MacKinnon, D. P. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol. Sci. 18, 233–239 (2007).

Aguinis, H., Beaty, J. C., Boik, R. J. & Pierce, C. A. Effect size and power in assessing moderating effects of categorical variables using multiple regression: A 30-year review. J. Appl. Psychol. 90, 94–107 (2005).

Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J. & Short, S. D. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 8, 379–386 (2017).

Lovibond, P. F. & Lovibond, S. H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 33, 335–343 (1995).

Gong, Y., Xie, X., Xu, R. & Luo, Y. Test report of the simplified Chinese version of the depression-anxiety-stress scale (DASS-21) among Chinese college students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 18, 443–446 (2010).

Shek, D. T. Perceived parental control and parent–child relational qualities in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Sex Roles 53, 635–646 (2005).

Nie M. Parental psychological control and autonomy support and college students’ future planning: the mediating role of dual autonomy (Master’s thesis, East China Normal University) (2018).

Hambleton, R. K. The international test commission guidelines for test adaptation. Psychologia 61, 101–118 (2018).

Greco, L. A., Baer, R. A. & Smith, G. T. Assessing mindfulness in children and adolescents: Development and validation of the child and adolescent mindfulness measure (CAMM). Psychol. Assess. 23, 606–614 (2011).

Liu, X. et al. Testing the reliability and validity of the child and adolescent mindfulness. scale (CAMM) among Chinese adolescents. Psychol Explor. 39, 250–256 (2019).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (The Guilford Press, New York, 2013).

Lachowicz, M. J. A general measure of effect size for mediation analysis (Doctoral dissertation). Vanderbilt University. (2018).

Johnson, P. O. & Fay, L. C. The Johnson-Neyman technique, its theory and application. Psychometrika 15, 349–367 (1950).

Holm, S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 6, 65–70 (1979).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903 (2003).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78 (2000).

Bandura, A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory (Prenctice Hall, Hoboken, 1995).

Gross, J. J. Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychol. Inq. 26, 1–26 (2015).

Chorpita, B. F. & Barlow, D. H. The development of anxiety: The role of control in the early environment. Psychol. Bull. 124, 3–21 (1998).

Erikson, E. H. Identity, youth, and Crisis. W.W. Norton. (1994).

Barnhofer, T., Duggan, D. S. & Griffith, J. W. Dispositional mindfulness moderates the relation between neuroticism and depressive symptoms. Personal Individ. Differ. 51, 958–962 (2011).

Liu, Q.-Q. et al. Mobile phone addiction and sleep quality among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 72, 108–114 (2017).

Williams, J. M. Mindfulness, depression and modes of mind. Cogn. Ther. Res. 32, 721–733 (2008).

Akin, A. & Akin, U. Mediating role of coping competence on the relationship between mindfulness and flourishing. Suma Psicológica. 22, 37–43 (2015).

Masten, A. S. & Narayan, A. J. Child development in the context of disaster, war, and terrorism: Pathways of risk and resilience. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63, 227–257 (2012).

Bajaj, B., Robins, R. W. & Pande, N. Mediating role of self-esteem on the relationship between mindfulness, anxiety, and Depression. Personal Individ. Differ. 96, 127–131 (2016).

Keye, M. D. & Pidgeon, A. M. Investigation of the relationship between resilience, mindfulness, and academic self-efficacy. Open J. Soc. Sci. 01, 1–4 (2013).

Luthans, F. & Youssef, C. M. Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management. Organ. Dyn. 33, 143–160 (2004).

Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 84, 116–122 (2011).

Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513–524 (1989).

Tang, Y.-Y. & Leve, L. D. Enhancing emotion regulation through mindfulness training: A promising approach for improving mental health. Trends Cogn. Sci. 26, 5–8 (2022).

Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D. & Greenberg, M. T. A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 12, 255–2704 (2009).

Peterson, C. & Seligman, M. E. P. Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004).

Conger, R. D. & Donnellan, M. B. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 58, 175–199 (2007).

Luthar, S. S. & Latendresse, S. J. Comparable, “risks” at the socioeconomic status extremes: Preadolescents’ perceptions of parenting. Dev. Psychopathol. 17, 207–230 (2005).

Gettler, L. T., McDade, T. W., Feranil, A. B. & Kuzawa, C. W. Longitudinal evidence that fatherhood decreases testosterone in human males. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 16194–16199 (2011).

Chaplin, T. M. & Aldao, A. Gender differences in emotion expression in children: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 139, 735–765 (2013).

Bedford, O. & Yeh, K. H. The history and the future of the psychology of filial piety: Chinese norms to contextualized personality construct. Front. Psychol. 10, 100 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the leaders and teachers of the three schools who helped and coordinated in this testing process, as well as the adolescent students who volunteered to participate in this study. The authors confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The authors confirm that all experimental protocols were approved by institutional research ethics committee of the South China Normal University. The authors confirm that informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardian(s).

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171091), and Graduate Research and Innovation Fund Project of School of Psychology, South China Normal University (PSY-SCNU202205).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. (Mingshi Du) and Y.G. (Yongshi Guo); methodology, M.D. and Z.W. (Zhonglin Wen); investigation, M.X. (Minli Xuan) and J.X. (Jing Xia); writing—original draft preparation, M.D. and Y.G.; writing—review and editing, M.D., Y.G., Z.W., M.X. and J.X.; project administration, Z.W., M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing of interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by institutional research ethics committee of the South China Normal University.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, M., Guo, Y., Wen, Z. et al. The mediating role of positive youth development and the moderating role of mindfulness in the relationship between parental psychological control and anxiety. Sci Rep 15, 39210 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18810-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18810-4