Abstract

Integrating palliative care (PC) into the intensive care unit (ICU) can enhance patient quality of life. The knowledge, attitudes, and practices of ICU physicians and nurses in palliative care (KAPPC) are essential for its successful implementation in the ICU. There remains insufficient evidence concerning the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of ICU physicians and nurses in palliative care in China. To investigate the current knowledge, attitudes, and practices of ICU medical staff regarding palliative care, we conducted a study utilizing an indigenized knowledge, attitude, and practice of palliative care (KAPPC) scale. This study aimed to assess the baseline KAPPC of ICU medical personnel in Dalian and explore the factors that influence these aspects in depth. The findings will serve as a reference for medical institutions to develop effective training programs for ICU staff in palliative care. This study uses quantitative and qualitative methodologies with a convenience sampling strategy, focusing on adult ICU medical staff at a tertiary hospital in Dalian. A cross-sectional design was utilized to evaluate the KAPPC of the medical personnel through the adapted KAPPC scale. Quantitative data was collected using the KAPPC scale. Descriptive analysis, linear regression, and Pearson’s (r) correlation analysis were performed to explore providers’ KAPPC, their influencing factors, and their correlations. Qualitative data was collected from participants’ textual responses through an open-ended question, and a content analysis method was employed to code, categorize, and extract themes from the collected text-based content. A total of 220 valid questionnaires were collected, resulting in an effective recovery rate of 84.62%. The overall score for knowledge, attitude, and practice among ICU medical staff in palliative care was 184.75 ± 25.74. The individual scores for knowledge, attitude, and practice were 9.59 ± 2.99, 91.59 ± 12.65, and 83.57 ± 15.49, respectively. The correlation analysis revealed a strong relationship between self-reported practice and confidence. The linear regression analysis demonstrated that several factors, including occupation, professional title, gender, ICU working experience, prior experience in palliative care education, and willingness to engage in palliative care training, significantly affected the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of ICU medical staff about palliative care. To address identified gaps in knowledge, attitudes, and practices, we propose a tripartite enhancement framework: (1) Role-specific competency development through differentiated training for physicians (end-of-life decision-making, multidisciplinary collaboration) and nurses (technical care, emotional support), coupled with palliative care certification; (2) Structural optimization via ICU-specific palliative pathways with rapid-response teams; and (3) Technology integration of Traditional Chinese Medicine techniques and electronic assessment systems for real-time monitoring. This integrated approach targets core barriers to palliative care delivery in Chinese ICUs, with future multi-regional studies needed to evaluate long-term efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intensive care units (ICUs) are specialized hospital wards where seriously ill patients receive treatment from dedicated care professionals and intensive care, primarily aimed at providing life-saving and life-sustaining interventions1. These units are equipped with advanced medical technology and staffed by highly trained personnel2. Advanced life support technology is often utilized to sustain life in the ICU. However, for patients in the late stages of illness, such interventions may not alter clinical outcomes and can increase the suffering of both the patients and their families while diminishing their quality of life. Some studies have shown that up to 75% of ICU patients experience varying levels of pain during invasive procedures or critical illness3. This pain can stem from multiple sources, including pre-existing conditions, medical interventions, and ICU environment. Given this reality, integrating palliative care (PC) is essential to mitigate the limitations of life-sustaining interventions. Research has demonstrated that implementing palliative care in the ICU yields positive benefits for patients and their families4,5.

However, the unique nature of the ICU environment, the complexity of medical decision-making, and the uncertainty of the patient’s illness present challenges for ICU medical staff in providing palliative care6. ICU physicians and nurses are the primary caregivers for patients. Their awareness and services are often regarded as significant facilitators or barriers in the development of PC. It remains crucial for ICU medical staff to strengthen their knowledge and attitudes toward palliative care. Knowledge-belief-action theory suggests that individuals can promote their practice only if they form positive beliefs based on their understanding of knowledge7. A full understanding of the current status of palliative care knowledge, attitudes, and practices of ICU medical staff and the factors influencing them is a prerequisite and foundation for the effective promotion of palliative care in the ICU. However, training in critical care areas predominantly emphasizes active disease treatment, with minimal focus on palliative care (PC)8. Specifically in mainland China, PC training is largely confined to oncology and geriatrics, leaving ICU staff underprepared8. While numerous cross-sectional studies have been conducted both domestically and internationally, these studies often fail to comprehensively cover the dimensions of knowledge, attitudes, and practices8. Additionally, the scales employed are typically self-developed, with their reliability and validity requiring further verification8,9. Research on palliative care knowledge, attitudes, and practices among ICU physicians and nurses in mainland China remains insufficient, warranting further investigation.

To investigate the current knowledge, attitudes, and practices of ICU medical staff regarding palliative care, we conducted a study utilizing an indigenized knowledge, attitude, and practice of palliative care (KAPPC) scale. This study aimed to assess the baseline KAPPC of ICU medical personnel in Dalian and explore the factors that influence these aspects in depth. The findings will serve as a reference for medical institutions to develop effective training programs for ICU staff in palliative care.

Methods

Study design

This research employs a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods, using a convenience sampling approach focused on adult ICU medical staff at a tertiary hospital in Dalian. A cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the KAPPC of medical personnel using the adapted KAPPC scale developed by Shuzhiqun et al.10. Quantitative data were collected through the KAPPC scale, while qualitative data were gathered from participants’ written responses to an open-ended question. These qualitative findings complemented the quantitative data, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing ICU medical staff’s knowledge, attitudes, and practices in palliative care.

Questionnaires

The data were collected through questionnaires that were developed by reviewing relevant literature and incorporating the clinical experiences of group members. The questionnaire featured general demographic information as well as a localized Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Palliative Care (KAPPC) scale tailored for ICU medical staff. This KAPPC scale was originally developed by Shuzhiqun et al.10 in 2021. The general demographic characteristics encompass 16 questions related to gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, professional title, occupation, monthly salary, educational background, type of ICU, duration of time spent in the ICU, religious beliefs, participation in palliative care training, the number of terminally ill patients treated in the past six months, experience in caring for a seriously ill immediate relative, and the loss of an immediate family member.

The knowledge assessment consists of five dimensions comprising a total of 15 items: basic concepts and goals (3 items), pain and symptom management (5 items), psychological and spiritual support (3 items), localization issues (1 item), and policy and organizational matters (2 items). Each correct response earns a score of 1, with total scores ranging from 0 to 15. Higher scores reflect a greater level of knowledge in palliative care.

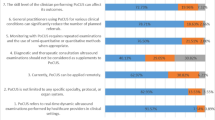

The attitude assessment consists of five dimensions encompassing a total of 24 items: perceptions of the threat posed by deterioration in terminally ill patients (5 items), perceptions of enhanced quality of life (5 items), perceptions of improved preparedness for death (5 items), perceptions of barriers to accessing palliative care (5 items), and perceptions of subjective norms surrounding palliative care (4 items). The attitudes were evaluated using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “totally disagree” (1) to “totally agree” (5). For the negative dimensions (Dimensions 1 and 4), the scores were reversed prior to calculation, ranging from “totally disagree” (5) to “totally agree” (1). The total score can range from 24 to 120, with higher scores indicating more favorable attitudes toward palliative care.

The practice assessment comprises two dimensions—confidence and self-reported practices—each consisting of 11 items, resulting in a total of 22 items. Both sections, confidence and self-reported practices, were evaluated using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “rather confident” (5) to “rather non-confident” (1) and “always” (5) to “never” (1). The overall score ranges from 22 to 110, with higher scores reflecting greater confidence and more palliative care practices. Scores across the three sections varied from 46 to 245, with higher scores indicating greater knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to palliative care among ICU medical staff. The scoring rate is calculated as (actual total score/highest possible score) * 100%. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the knowledge, attitude, and practice dimensions of the questionnaire were 0.686, 0.868, and 0.958, respectively, demonstrating good reliability and validity.

Ethics procedure

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the ethics committees of the First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University (Approval No. PJ-KS-KY-2024-687). All participants provided informed consent after the investigator presented the purpose of the study. Each participant volunteered to participate in this study and the information filled out was confidential and anonymous.

Data collection

A questionnaire survey was conducted using a convenience sampling method among the medical staff in the ICU. The criteria for inclusion in the study were: (1) certified doctors or nurses; (2) at least one year of experience in clinical medical or nursing work in the ICU; (3) willingness to adhere to the research process and provide consent to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were: (1) doctors and nurses undergoing training or internship in the ICU during the survey period. The data were gathered by a well-established survey team. Each team member underwent comprehensive training to ensure consistent and standardized data collection. Before the formal investigation, the team members met with the heads of each ICU in the hospital to explain the survey’s purpose and to emphasize the importance of confidentiality. Following the acquisition of informed consent and with the assistance of the department head, the team members shared the link to the electronic questionnaire with various departmental work groups. The questionnaire utilized a standardized guide to clarify its purpose, significance, and instructions for completion. Team members provided prompt online responses to any inquiries from ICU medical staff. Participants had the option to complete the questionnaire using either a mobile device or a computer. To ensure data quality, each item in the questionnaire was designated as mandatory. Additionally, a set of “test” items was incorporated to assess the participants’ understanding and the consistency of their responses, such as reversed-scored items to detect response consistency, and duplicate questions with inverted wording to assess attentiveness. These test items were strategically placed throughout the questionnaire to verify response validity.

Participants completed the questionnaires independently, taking an average of approximately 5 to 10 min. Each IP address was permitted only one response, and any questionnaire completed in less than 5 min was deemed invalid. According to the “Kendall sample size estimation” principle11the recommended sample size should be 5 to 10 times the number of variables. In this study, we examined 16 demographic variables, along with five dimensions, each from the Knowledge and Attitude Scales and two dimensions from the Practice Scale. The minimum sample size was calculated as (16 + 5 + 5 + 2)*5/(1-0.2) = 175, which includes a 20% adjustment for potential invalid responses. During data collection, the researcher reviewed questionnaire completion and submission daily, assessed logical consistency, identified outliers and missing values, documented these, and regularly exported and backed up the data.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were employed to assess the demographic characteristics of the participants as well as their knowledge, attitudes, and practices scores. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were summarized using frequency and proportion. In the univariate analysis, a two independent samples t-test was employed to compare two groups of data that met the criteria of variance homogeneity and normal distribution. ANOVA was utilized to compare multiple groups of data. In cases where the data were not normally distributed, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied for two-group comparisons, while the Kruskal-Wallis test (H test) was used for multiple-group comparisons. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships among the palliative care knowledge, attitudes, confidence, and self-reported practices of ICU staff. Additionally, multiple linear regression analysis was performed to identify the factors influencing the palliative care knowledge, attitudes, and practices of ICU medical personnel. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Content analysis

A content analysis method was employed to code, categorize, and extract themes from the collected text-based content, providing insights into the depth and richness of participants’ understanding and attitudes towards palliative care.

Results

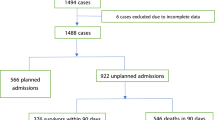

Characteristics of the study population

In this survey, 260 questionnaires were distributed. After excluding those with more than 70% consecutive and repetitive responses, a total of 40 invalid questionnaires were eliminated, resulting in a valid response rate of 84.62%. Among the 220 ICU physicians and nurses surveyed, 83.64% identified as female, 65.45% were aged between 31 and 50, and 25.45% held a master’s degree or higher. Additionally, 72.27% of the respondents were nurses, while only 13.64% had received training in palliative care education. An impressive 86.36% of respondents indicated a willingness to participate in palliative care, primarily because they believed it could enhance patients’ quality of life (78.95%). On the other hand, 73.33% of the respondents indicated that heavy work pressure was the main reason for their reluctance to attend palliative care training (Table 1).

The questionnaire produced a total score of 184.75 ± 25.74, reflecting a scoring rate of 75.41%. The scores for knowledge, attitude, and practice were 9.59 ± 2.99, 91.59 ± 12.65, and 83.57 ± 15.49, respectively, with corresponding scoring rates of 63.94%, 76.32%, and 75.98%.

Knowledge

The mean knowledge score among respondents was 9.59 ± 2.99, resulting in a scoring rate of 63.94%. The three items with the lowest scores in the knowledge dimension were: “Item 1, which states that providing palliative care requires emotional separation,” “Item 10, asserting that men generally process grief faster than women,” and “Item 7, suggesting that the use of drugs capable of causing respiratory depression is an appropriate treatment for severe dyspnea,” with scoring rates of 20%, 23.64%, and 37.73%, respectively. In contrast, the two items that received the highest scores were “Item 2, addressing psychological, social, and psychiatric issues vital to the efficacy of palliative care teams,” and “Item 13, emphasizing the importance of the multidisciplinary composition within palliative care teams.” Physicians demonstrated a higher palliative care knowledge than nurses, with mean scores of 10.39 ± 2.36 and 9.28 ± 3.16, respectively. Additionally, five items had correct response rates below 60.00%, highlighting areas for improvement. (Table 2)

The linear regression analysis (Table 6) reveals that the factors associated with higher knowledge scores include being a doctor (β = -0.187, P = 0.012), holding a higher professional title (β = 0.216, P = 0.002), having more ICU working experience (β = -0.298, P = 0.003), participating in palliative care education (β = -0.204, P = 0.001), and expressing a willingness to accept palliative care training (β = -0.233, P < 0.001). (Table 6)

Attitude

The mean score for the attitudes scale was 91.59 ± 12.65, resulting in an scoring rate of 76.32%. Among the various dimensions assessed, “cognition of improving quality of life” received the highest mean score, while the dimension with the lowest score was “cognition of threat to terminal patient deterioration.” Specifically, Item 13, which addressed “better emotional communication with critically ill patients,” achieved the highest mean score, whereas Item 19, concerning “the complexity of symptoms in critically ill patients,” recorded the lowest mean score. In the attitude component, physicians scored higher than nurses on “subjective norms for providing palliative care” (4.18 ± 0.63,3.66 ± 0.82). However, nurses outperformed physicians in “cognition of threat to terminal patient deterioration” (3.52 ± 1.11, 3.11 ± 0.90). (Table 3)

The linear regression analysis indicates that several variables are significantly correlated with higher attitude scores: being female (β = 0.205, P = 0.006), holding a higher professional title (β = 0.270, P < 0.001), having more ICU working experience (β = 0.222, P = 0.006), and expressing a willingness to accept palliative care training (β = -0.211, P = 0.001). (Table 6)

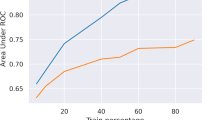

Practice

The study revealed that ICU medical staff achieved a mean score of 83.57 ± 15.49 on the palliative care practice dimension, translating to a score rate of 75.98%. The confidence scores and self-reported practices were 40.63 ± 8.27 and 42.94 ± 8.33, respectively, with corresponding score rates of 73.88% and 78.07%. Item 1, “to relieve pain and discomfort in terminally ill patients,” received the highest mean score. In contrast, Item 11, which pertains to care and support for bereaved families, recorded the lowest mean score. Confidence in palliative care was lower than in self-reported practices. Nurses reported slightly higher palliative care confidence than physicians.(3.71 ± 0.78, 3.65 ± 0.67) (Table 4). Correlation analysis revealed that confidence exhibited a strong correlation with self-reported practice, with a correlation coefficient of 0.743. (Table 5)

The linear regression analysis indicates that a higher professional title (β = 0.167, P = 0.0034) is associated with increased confidence scores. Additionally, being female (β = 0.171, P = 0.030), having a higher professional title (β = 0.189, P = 0.024), and having more ICU working experience (β = 0.172, P = 0.048) are linked to higher self-reported practices. (Table 6)

Discussion

Knowledge

The study found that ICU medical staff had a mean palliative care knowledge score of 9.59 out of 15, equating to a score rate of 63.94%. This score was slightly lower than the 69% reported by Wang Yu12 for ICU nurses in two tertiary hospitals and significantly lower than the 79.68% reported by Le Xiao13 for geriatric nurses. These findings suggest that ICU medical staff possess insufficient knowledge of palliative care. This issue may be attributed to the distinct medical environment of the ICU, where the primary focus is on life-saving interventions. The elevated stress levels inherent in ICU settings significantly impede medical personnel from allocating adequate time and resources to the acquisition of knowledge regarding palliative care, consequently diminishing their capacity to concentrate on palliative care14. The analysis of the highest and lowest scoring items reveals that, although most ICU staff understand the fundamental principles and objectives of palliative care, they struggle with effectively implementing best practices in psychological and psychiatric care, as well as managing complex symptoms. This highlights the pressing need for focused education and training programs that emphasize psychological and psychiatric care, pain management, and the management of end-stage symptoms15. While many respondents indicate that palliative care requires emotional detachment, the research emphasizes that emotional engagement is essential for fostering understanding and support between healthcare professionals and patients16,17. This engagement is critical for effective palliative care. Therefore, medical institutions should improve training for ICU staff in emotional resilience to help maintain their emotional involvement. Mental health support programs, like meditation and mindfulness therapy, enhance stress management, boost confidence, and promote professionalism18.

ICU physicians demonstrated a greater knowledge of palliative care compared to nurses, which is consistent with Li Liumeng’s findings19 regarding palliative care cognition among domestic healthcare professionals. This difference may stem from their distinct educational backgrounds and responsibilities, as doctors concentrate on clinical decision-making while nurses emphasize nursing skills20.

Moreover, there is a noticeable lack of awareness regarding traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) within palliative care. Ning Xiaohong21 highlighted that TCM techniques focus on alleviating patients’ pain and other forms of discomfort through non-pharmacological therapies, which offer significant support in palliative care settings. It is recommended that healthcare professionals in ICU settings receive specialized training in TCM methods and non-pharmacological interventions21,22. Such training would equip them with more effective strategies to alleviate symptoms like pain and discomfort in patients.

Attitude

The study reveals that the mean palliative care attitude scores among ICU medical staff were 91.59 ± 12.65, translating to a score rate of 76.32%. This result exceeds the 69.14% reported in Ren Ying’s survey23 of 425 clinical medical professionals and closely aligns with Teng Xiaohan’s findings24 in Shanghai, which recorded a rate of 74.20%. However, it is notably lower than the 85.4% observed among 210 medical staff in Taiwan25. The dimension with the highest score suggests that a significant majority of ICU medical staff demonstrate a positive foundational attitude toward palliative care and align with its fundamental principles. In the attitude dimension with the lowest score, some respondents indicated challenges in confronting the dying process, underscoring the psychological difficulties in palliative care practices. This reluctance to engage with death has a notable impact on the effectiveness of palliative care. This issue may stem from the influence of traditional cultural values on ICU medical staff, which makes it difficult for them to confront death directly26. It is recommended that death education and training be delivered through courses, lectures, or case discussions to assist medical staff in understanding death appropriately. Moreover, respondents noted that the complexity of symptoms in critically ill patients presents a significant barrier to the provision of palliative care. This corresponds to a lack of knowledge about palliative care. Implementing systematic training on end-of-life symptom management—particularly for issues such as intractable pain, dyspnea, nausea, and vomiting—can enhance healthcare workers’ abilities to recognize and manage these symptoms effectively27. This training not only improves their competency in addressing complex symptoms but also contributes to increased patient comfort and an improved quality of life.

Moreover, physicians display a more favorable view of subjective norms related to palliative care, recognizing its significance and the essential role of multidisciplinary teams more than nurses. This phenomenon may be attributed to the central role that physicians play in the formulation of clinical decisions, whereas nurses tend to concentrate more on the execution of specific technical procedures28. However, nurses generally exhibit a more positive attitude toward recognizing the threats posed by terminal patient deterioration. This may be attributed to their direct involvement in daily patient care, which enhances their appreciation for the value of palliative care and contributes to their sense of professional fulfillment29. In contrast, physicians often find satisfaction in metrics such as “cure rates.” Consequently, they may experience frustration when confronted with patient deaths, which can affect their acknowledgment of the importance of palliative care. Therefore, medical institutions should develop palliative care training strategies tailored to the unique characteristics of physicians and nurses. Facilitate the involvement of nurses in multidisciplinary palliative care teams, define their roles in decision-making, and improve their understanding of palliative care standards. Additionally, it is essential to strengthen medical education regarding the concept of death among physicians.

Practice

The study revealed that ICU medical staff achieved a mean score of 83.57 ± 15.49 in the practice dimension, translating to a score rate of 75.98%. These results closely correspond with those reported by Shenyang30 for nurses working in the tumor ward, ICU, and palliative care ward of a tertiary hospital. The study revealed that while respondents typically managed to reduce pain and discomfort in end-of-life patients, their confidence in doing so was low. A deficiency in professional skills related to pain management among ICU staff may lead to diminished confidence, as suggested by previous research indicating a correlation between healthcare professionals’ knowledge and confidence31. Consequently, managers must enhance training and education in sedation and analgesia31.

Item 11, which pertains to the care and support offered to bereaved families, recorded the lowest scores in terms of both confidence and self-reported practices. This low performance may be linked to the cultural taboo surrounding discussions of death within traditional Chinese culture32. Additionally, ICU staff may not perceive the care and support of bereaved families as part of their primary responsibilities33. Therefore, it is recommended that multidisciplinary collaboration be strengthened, emphasizing the importance of working with social workers, psychotherapists, and spiritual support personnel34.

Nurses generally exhibit higher confidence in palliative care than physicians, likely due to their more frequent exposure to this area of practice. In contrast, physicians often take the lead in making critical treatment decisions, such as determining when to withdraw life support. This responsibility exposes them to significant ethical and legal risks, which can contribute to feelings of uncertainty and, ultimately, diminish their confidence. Future research should prioritize refining measurement scales to include key physician behaviors, such as participation in advance care planning (ACP)35 and decisions regarding the withdrawal of life support in palliative care. Furthermore, it is essential to investigate the disparities in palliative care practices between physicians and nurses to improve interdisciplinary coordination.

Influencing factors of KAPPC

The heightened attitudes and practices related to palliative care observed among female ICU medical staff may be a result of the significant representation of female participants (83.64%) in this study. Future research could broaden the sample size to further explore the palliative care performance of female ICU medical staff using qualitative methods. Professional title significantly influences the KAPPC of ICU medical staff. It might be because higher professional titles are associated with greater work experience and advanced professional skills. These findings are consistent with Zhao Jing’s survey36 of 307 nurses in tertiary hospitals. Participants in palliative care education exhibited a significant enhancement in KAPPC, suggesting that structured educational interventions not only augment knowledge and attitudes toward palliative care but also markedly improve the clinical performance of healthcare professionals. This finding underscores the critical role of systematic training in fostering proficiency in palliative care practices among medical personnel. A significant 86.36% of respondents expressed a desire to enhance their professional knowledge through education and training. However, 13.64% were reluctant to participate in palliative care education and training. This hesitation was largely attributed to high work pressures and the difficulties associated with finding time to dedicate to palliative care-related learning. Medical institutions ought to implement flexible learning modalities for ICU personnel, incorporating online courses and case studies to mitigate the pressure posed by extended centralized training programs. Furthermore, it is essential to enhance participation incentives, such as the provision of post-training certifications and opportunities for career advancement, to foster greater engagement and professional development among staff37.

The analysis of textual content derived from open-ended questions

Through the process of encoding and classifying the text data while excluding irrelevant information, two primary themes and nine sub-themes were identified. In terms of the management system, 21.4% of participants expressed a desire for enhanced hospital resource support and palliative care clinical guidelines. Significantly, over 80% of those advocating for this initiative held higher professional titles, such as senior physicians and nurse supervisors, indicating that individuals with substantial clinical experience prioritize systematic improvements. 15% of participants recommended implementing flexible course formats, such as case discussions, experience exchanges, and online micro-videos, to improve the dissemination of palliative care knowledge. Moreover, it is crucial to integrate palliative care education into the core curriculum of medical colleges to establish a strong theoretical foundation for its advancement38. Two participants notably proposed the integration of traditional Chinese medicine techniques, specifically acupoint application analgesia, into clinical training programs39,40. Furthermore, one participant recommended the incorporation of palliative care screening assessment forms into hospital electronic medical records, aimed at improving the early identification of patients requiring palliative care in the ICU41. Additionally, it is advisable for medical institutions to mitigate the workload of ICU personnel and to establish incentive frameworks that actively encourage the promotion of palliative care within the ICU setting.

Critically, these qualitative insights synergistically enhanced quantitative findings through three evidence integrations: (1) Explaining practice-confidence discrepancies via participant narratives contextualizing low bereavement support scores (e.g., “After pronouncing death, we must immediately prepare for the next critical admission” - Nurse, 15 years ICU); (2) Operationalizing professional title-KAPPC correlations by demonstrating how senior clinicians drive systemic change—quantified by 80% of high-title staff demanding resource/guideline optimization; (3) Validating TCM integration as a strategic priority despite knowledge deficits, evidenced by unsolicited emphasis on acupoint analgesia.

Conclusion

ICU medical staff exhibit limited knowledge alongside moderate attitudes and practices in palliative care, with key influencing factors including occupation, gender, professional title, ICU experience, palliative care training exposure, and willingness to pursue further education. To bridge these gaps, we recommend a tripartite strategy: First, implement role-specific competency development through advanced physician training in end-of-life decision-making, multidisciplinary collaboration, and death education, complemented by enhanced nursing training in technical care, emotional support, and clinical decision-making participation, all reinforced by palliative care certification linked to career advancement; Second, optimize structural frameworks via ICU-specific palliative care pathways incorporating rapid-response teams (e.g., social workers, psychologists); Third, deploy technology-enabled solutions through integration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) techniques (e.g., acupoint analgesia) into standardized curricula and enhancement of electronic health records with automated palliative care assessment modules for real-time monitoring. Collectively, this integrated approach targets knowledge deficits through stratified education, systemic barriers via workflow redesign, and quality gaps via digital innovation—establishing a transformative foundation for palliative care delivery in Chinese ICUs. To validate and scale these initiatives, future multi-regional studies should evaluate long-term training efficacy.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author, without undue reservation.

References

Bowker, S. L. et al. Incidence and outcomes of critical illness in Indigenous peoples: a systematic review protocol[J]. Syst. Reviews. 11 (1), 65 (2022).

Firissa, Y. B. Critical care service transformation at the ALERT comprehensive specialized hospital, A case study. Pan-African J. Emerg. Crit. Care, 2(1). (2024).

Adineh, M. et al. I was lying on a bed just like the wounded in the war: A qualitative study explaining the experiences of brain injury patients hospitalized in ICU[J] (2023).

Poi, C. H. et al. Palliative care integration in the intensive care unit: healthcare professionals’ perspectives–a qualitative study[J]. BMJ Supportive Palliat. Care. 3 (e3), 14 (2023).

Michels, G., Schallenburger, M. & Neukirchen, M. Recommendations on palliative care aspects in intensive care medicine[J]. Crit. Care. 27 (1), 355 (2023).

Ito, K. et al. Primary palliative care recommendations for critical care clinicians[J]. J. Intensive Care. 10 (1), 20 (2022).

Sitompul, A. Correlation And Integration Between Faith, Knowledge And Behavior. (2020).

Shiju, W. & Gong Guomei. Research status quo of knowledge,attitude and practice of nursing staff in China on hospice care [J]. Chin. Nurs. Res. 32 (21), 3372–3374 (2018).

Pan Qini, H. H. et al. Tao Pan Xiao, Survey on knowledge,belief and practice of hospice care among hospice care workers:the influencing factors [J]. Journal of Nursing Science 36(15):20–22,26 (2021).

Shu, Z. et al. Instrument development of health providers’ knowledge, attitude and practice of hospice care scale in China[J]. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 36 (2), 364–380 (2021).

Wang, X. & Ji, X. Sample size Estimation in clinical research: from randomized controlled trials to observational studies[J]. Chest 158 (1), S12–S20 (2020).

Wang, Y., Pengfei, S. & Xiujun, L. Wang guiying.the status quo and influencing factors of core competencies of ICU nurses in palliative care [J]. Chin. J. Mod. Nurs. 29 (6), 728–734 (2023).

Le Xiao, W. et al. Status and influencing factors of knowledge, attitude and practice on palliative care of geriatric nursing staffs[J]. Chin. Nurs. Res. 36 (21), 3884–3889 (2022).

Alshehri, H., Olausson, H. & Öhlén, S. Factors influencing the integration of a palliative approach in intensive care units: a systematic mixed-methods review[J]. BMC Palliat. Care. 19, 1–18 (2020).

Doherty, C. et al. Easing suffering for ICU patients and their families: evidence and opportunities for primary and specialty palliative care in the ICU[J]. J. Intensive Care Med. 39 (8), 715–732 (2024).

Moens, K., Bilsen, J. & Zambrano, S. How do palliative care clinicians use their emotions during end-of-life encounters? [J]. Eur. J. Pub. Health. 34 (Supplement_3), ckae144 (2024).

Espejo-Fernández, V. & Martínez‐Angulo, P. Psychosocial and emotional management of work experience in palliative care nurses: A qualitative exploration[J]. Int. Nurs. Rev. 72 (1), e13006 (2025).

Lovell, T. et al. Fostering positive emotions, psychological well-being, and productive relationships in the intensive care unit: a before-and-after study[J]. Australian Crit. Care. 36 (1), 28–34 (2023).

Li Liumeng, G. et al. Meta-analysis of the Study on Cognition and Attitude of Domestic Medical Staff to Hospice Care,Medicine & Philosophy, 42 (15):45–50 (2021).

Adda, M. et al. Organization of clinical research in intensive care units: A scoping review[J]. Australian Crit. Care (2024).

Ning Xiaohong. Research on hospice/palliative care in Mainland china: current status and future development Direction[J]. Palliat. Med. 33 (9), 1129–1130 (2019).

van Veen, S. et al. Non-pharmacological interventions are feasible in the nursing scope of practice for pain relief in palliative care patients: a systematic review[J]. Palliat. Care Social Pract. 18, 26323524231222496 (2024).

Ren Ying, Y. et al. A survey of medical staff’s attitude towards palliative care and hospice care behavior[J]. J. Nurs. Sci. 39 (5), 66–69 (2024).

Xiaohan, T., Liei, J., Zhiqun, S., Xiaoming, S. & Yifan, X. Survey on attitude and influencing factors of hospice care among health providers in Shanghai[J]. Chin. J. Gen. Practitioner. 20 (5), 556–561 (2021).

Huang, L. C., Tung, H. J. & Lin, P. C. Associations among knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward palliative care consultation service in healthcare staffs: A cross-sectional study[J]. PLoS One. 14 (10), e0223754 (2019).

Barnett, M. D., Reed, C. M. & Adams, C. M. Death attitudes, palliative care self-efficacy, and attitudes toward care of the dying among hospice nurses[J]. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings. 28, 295–300 (2021).

Araujo, M. C. R., da Silva, D. A. & Wilson, A. Nursing interventions in palliative care in the intensive care unit: A systematic review[J]. Enfermería Intensiva. 34 (3), 156–172 (2023).

Braam, A. et al. Similarities and Differences between Nurses’ and Physicians’ Clinical Leadership Behaviours: A Quantitative Cross-Sectional Study[J]. Journal of Nursing Management, : 8838375 (2023). (2023)(1).

Moran, S., Bailey, M. E. & Doody, O. Role and contribution of the nurse in caring for patients with palliative care needs: A scoping review[J]. Plos One. 19 (8), e0307188 (2024).

Shen, Y. The Study of Nurses’ Hospice Knowledge and Behavior Scale Construction and Application [D] (Clinical Medicine University, 2020).

Hou Chunlei, Z., Die, D. & Yingchao Sudan. Nurses’ knowledge,attitudes,and behaviors toward the ABCDE Bundle nursing for sedation and analgesia in Intensive Care Units[J]. Chinese Journal of Nursing, 54 (10):1529–1534 (2019) (2019).

Hahne, J. et al. Chinese physicians’ perceptions of palliative care integration for advanced cancer patients: a qualitative analysis at a tertiary hospital in changsha, China[J]. BMC Med. Ethics. 23 (1), 17 (2022).

Renckens, S. C. et al. Experiences with and needs for aftercare following the death of a loved one in the ICU: a mixed-methods study among bereaved relatives[J]. BMC Palliat. Care. 23 (1), 65 (2024).

Stilos, K., Takahashi, D. & Nolen, A. E. The role of the social worker at the end of life: paving the way in an academic hospital quality improvement initiative[J]. Br. J. Social Work. 51 (1), 246–258 (2021).

Yamamoto, K., Yonekura, Y. & Nakayama, K. Healthcare providers’ perception of advance care planning for patients with critical illnesses in acute-care hospitals: a cross-sectional study[J]. BMC Palliat. Care. 21 (1), 7 (2022).

Zhao Jing, Z. et al. Current situations and influencing factors of hospice care-related knowledge, attitude and practice of nurses in general hospitals [J]. Mod. Clin. Nurs. 19 (08), 13–19 (2020).

Periyakoil, V. S. et al. Incentives for palliative care[J]. J. Palliat. Med. 25 (7), 1024–1030 (2022).

Xue, B. et al. Attitudes and knowledge of palliative care of Chinese undergraduate nursing students: A multicenter cross-sectional study[J]. Nurse Educ. Today. 122, 105720 (2023).

Yang, Q. et al. Summary of evidence on traditional Chinese medicine nursing interventions in hospice care for patients with advanced cancer[J]. Geriatr. Nurs. 61, 240–249 (2025).

Jin, H. et al. External treatment of traditional Chinese medicine for cancer pain: A systematic review and network meta-analysis[J]. Medicine 103 (8), e37024 (2024).

Zhang, M., Zhao, Y. & Peng, M. Palliative care screening tools and patient outcomes: a systematic review[J]. BMJ Supportive Palliat. Care. 14 (e2), e1655–e1662 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the physicians and nurses who took time out of their busy schedules to participate in this study. We would like to thank all the.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Scholarship Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SRH and BW conducted the study conception and design. BW, MC, and XML collected the data. SRH, BW, MC, and XML analyzed the data. SRH drafted the initial manuscript, and Majima tomoko and TYS revised and polished it. All authors were responsible for critical revisions and approval of the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical issues

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the ethics committees of the First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University (Approval No. PJ-KS-KY-2024-687). All participants provided informed consent after the investigator presented the purpose of the study. Each participant volunteered to participate in this study and the information filled out was confidential and anonymous.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, S., Wang, B., Chen, M. et al. Current status of knowledge, attitudes, and practices among ICU physicians and nurses regarding palliative care in China. Sci Rep 15, 34954 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18909-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18909-8