Abstract

Duodenal neuroendocrine tumours (duodenal NETs) are uncommon tumours, accounting for 3% of all duodenal malignancies. They can have varied clinical behaviour and often can have metastatic disease at presentation. Due to the unpredictable clinical behaviour, European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society guidelines recommend the consideration of resection of these lesions if the disease is localised. Endoscopic resection is challenging in the duodenum due to the thin mucosal wall and difficulty with access depending on the location of the lesion. We reviewed our experience of 42 non-ampullary duodenal NETs managed at a single centre. 81% had resection for the duodenal NETs of which 50% were resected endoscopically. Endoscopic outcomes were excellent with macroscopic resection of all lesions, there was 1 perforation and no 30-day mortality. Of cases considered for surgery, 38% had nodal involvement and some metastatic disease. Lesions of grade 2 and those larger than 15 mm in size had a high risk of nodal involvement. A careful selection of cases with accurate staging using EUS, PET imaging and careful lesion assessment enables high success rates for endoscopic resection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Duodenal neuroendocrine tumours (duodenal NETs) account for 2.8% of all the neuroendocrine tumours (NET)1,2,3. Currently available therapeutic options include conservative management, endoscopic resection, limited duodenal resection and pancreatoduodenectomy4,5,6. Duodenal neuroendocrine neoplasms can be classified by their histological type which are neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) and neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC). They can also be further classified as ampullary and non-ampullary duodenal NETs. Ampullary tumours are rare and often can be higher grade and have a generally poor outcome. Non-ampullary duodenal NETs are more common and frequently incidentally found at time of endoscopy for other indications. Duodenal NETs can also be classified as to secretion of hormones as functional or non-functional tumours (The most common hormone secretion being gastrin). There are mainly 5 subtypes of duodenal NETs: duodenal gastrinoma, duodenal somatostatinoma, nonfunctioning duodenal NET, duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma, and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma. VIPoma and GRFoma can also arise from duodenum.

Most duodenal NETs arise in the first part of the duodenum. The behaviour of duodenal NETs can be rather varied7. Key features for the pathological diagnosis of NETs include positive tumour staining for the NET markers Syn and CgA by immunostaining. Tumour proliferative activity clarifies tumour grade, and this is evaluated by the number of mitotic figures, or the Ki-67 index. Based on these indices, NETs are classified into 3 grades: G1 (number of mitotic figures < 2 and/or the Ki-67 index < 2%); G2 (number of mitotic Figures 2–20 and/or Ki-67 index 3%−20%); and G3 (number of mitotic figures > 20 and/or the Ki-67 index > 20%).

It is of utmost importance that a thorough assessment of the lesion and staging of the disease is performed, prior to the decision on therapeutic modality being made. Besides the standard gastroscopy, an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) should be performed prior to considering endoscopic resection to exclude muscle layer involvement. EUS may not be required if there is evidence of metastatic disease, or the lesion is deemed not suitable for endoscopic resection. All patients should have conventional cross-sectional imaging (computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) to stage for evidence of nodal disease. There is a risk of nodal involvement even with small lesions hence, functional imaging (Gallium 68 DOTATATE PET scan or Octreoscan +/− FDG PET) should also be performed for accurate staging8,9,10,11. Ideally, the decision on treatment modality should be made in a multidisciplinary setting, considering the size and location of the tumour, depth of invasion, presence of distant spread, feasibility of resection, patients’ comorbidities and their performance status12,13.

Endoscopic resection is generally indicated for non-functional, non-ampullary lesions which are less than 10 mm in size, limited to the submucosal layer, and do not have locoregional or distant metastasis14,15,16. Surgical resection is generally indicated for lesions exceeding 20 mm in size (i.e. high risk of LN involvement), in the presence of LN metastases, and for peri-ampullary lesions. Whilst the optimum management strategy for lesions of 10–20 mm remains controversial, evidence from a recent meta-analysis suggests that endoscopic resection could be considered as a first line treatment for these lesions17,18. Currently practised endoscopic resection methods are endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), EMR with a ligation device (EMR-L), full-thickness resection via devices such as the FTRD® System (Ovesco Endoscopy AG), EMR after pre-cutting (EMR-P) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)19,20,21,22. Within the anatomical constraints of the duodenum, EMR is relatively straightforward and quicker than ESD. Whilst the complication rates are higher in ESD, it achieves higher en-bloc resection rates in comparison to EMR23,24,25. The choice of endoscopic resection technique largely depends on tumour features, location and the expertise of the endoscopist26.

We have included the data on cases that underwent surgical resection as a comparison in terms of long term recurrence risk and perioperative surgical outcomes. In light of this, we demonstrate that the endoscopic management can be safe and effective for the management of duodenal NETs within a multidisciplinary setting through our experience.

Methodology

Study design and participants

This was a single centre, retrospective, observational study conducted at King’s College Hospital, London, UK. This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki, and the findings are reported in line with Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies27. This study was registered with the Kings College Hospital audit department (Registration number 239). The ethical clearance and informed consent were waived by NHS Health Research Authority.

The inclusion criteria were (1) age 18 years or older (2) had histological confirmation of NET either through a pre-resection biopsy, endoscopy resection or surgical resection (3) had a follow up of at least 12 months following resection. Patients who had ampullary NET were excluded from the study.

A list of individuals, who either presented or were referred with duodenal NETs between 1 st of January 2006 to 31 st of March 2023, was obtained from the local NET database. This list of potential participants was then screened against the inclusion criteria.

Intervention

No intervention was conducted as part of this study. All of the included participants were retrospectively followed up until their last clinic encounter.

Data collection

Data were collected on basic demographics (age, gender and ethnicity), medical history, medication details, findings on endoscopy, imaging performed and their findings, treatments and follow up events. The data were mainly collected from hospital data management system and was cross checked with their general practitioners’ records.

For endoscopy examinations (both gastroscopy and EUS), the electronic reports were reviewed for the following information – size, number, location of tumour, endoscopic appearance, Paris classification and, feasibility of the tumour for endoscopic resection. Endoscopic complete resection was defined as the absence of any identifiable residual tumour on Endoscopy.

All of the cross-sectional and functional imaging (Gallium 68 DOTATATE PET scan or Octreoscan +/− FDG PET) reports, performed both at the time of diagnosis and during follow-up, were reviewed for the presence of lymph node and distant metastasis.

Histological assessment was performed in accordance with WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system28,29. The following data was obtained from the histology reports - histopathological type, tumour size, depth of invasion and presence of lymphatic and blood vessel invasion. Tumours were staged using European Neuroendocrine Tumour (ENETS) TNM classification14.

Statistical analysis

R studio (version 4.3.3) software was used for all of the statistical analysis30. Continuous variables were presented as means or medians with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were described as frequencies and percentages. Descriptive data were summarised using tables and figures. The differences in patient characteristics, resection status and recurrence between endoscopic and surgical resection groups were compared using Fisher’s exact test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Study population characteristics

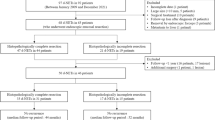

A total of 45 patients qualified for the study. Three patients were removed due to lack of data for analysis. Among those 42 patients who were included in the final analysis, 19 (45.2%) were males. Median age was 69 (IQR, 57–77). The majority of the tumours were found in the first part of the duodenum (78%) and were non-functional (83%). The median tumour size was 12 mm (IQR, 10–15.5 mm) and the majority (62%) of tumours demonstrated Paris Is morphology on assessment. Pre-resection biopsy showed that the majority of the lesions were well differentiated G1 subtype (76.2%). The baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. Figure 1 demonstrates a few commonly encountered endoscopic appearances of duodenal NETs.

Endoscopic appearances of non-ampullary duodenal neuroendocrine tumours (duodenal NET) (a) IIa + c 12 mm lesion in the second part of the duodenum with convergence of folds, these are high risk features for deep invasion and not suitable for endoscopic resection, (b) 1 s lesion in the duodenal bulb with erythematous central ulceration (c) 5 mm submucosal lesion in duodenal bulb.

Intervention

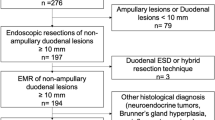

Overall, thirty-four (81%) patients had resection for their duodenal NETs. Amongst those, 21 (50%) underwent endoscopic resection whilst 13 had surgical resection. The types of endoscopic and surgical resections performed are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Table 2 presents the comparison between endoscopic and surgical resection with regards to the tumour characteristics and follow up events. The majority of the endoscopic resection was performed under general anaesthesia (n = 12, 57.1%). Nearly half of the patients who underwent endoscopic resection had tumour size of > 10 mm (n = 9, 42.9%). Surgical resection was commonly performed for tumours > 10 mm (n = 11, 84.6%) and for those who had locoregional metastatic disease (n = 5, 38.5%).

One (4.8%) patient suffered perforation during the endoscopic resection (recognised intraprocedurally and was closed with clips) who required 2 days of in patient stay following their procedure. The median length of inpatient stay following endoscopic resection was zero days whilst for surgical resection, it was 10 days. Macroscopically complete resection margin was observed in all of the patients who had endoscopic resection. Among them, 12 (57.1%) had histologically confirmed R0 resection.

For those who had surgical intervention, macroscopically complete resection was achieved in 11 (84.6%) patients whilst 9 (69.2%) had histologically confirmed R0. Details of lymph node involvement on CT, EUS and post resection histology are summarised as Supplementary Table 1. In two patients (15%), the lymph node involvement was detected on post resection histology although the staging CT did not detect lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis. It is noteworthy that both of these patients did not have EUS prior to their resection.

Eight (19.1%) patients were managed conservatively; the majority of them had multiple comorbidities and were deemed high-risk for either endoscopic or surgical intervention. Three patients were kept on endoscopic surveillance and three received PRRT/SSA. Two patients received symptomatic management only.

Follow up and recurrence

All of the patients who underwent resection had their first follow up at 6–12 months. Patients who had endoscopic resection and had positive/unclear margins (R1 and RX (n = 7, 33.7%) were kept under annual endoscopic surveillance and cross-sectional imaging, where deemed necessary. Patients who underwent surgery, received surveillance through cross-sectional imaging (see Table 3).

Median duration of follow up for endoscopic and surgical resection groups were 1135 and 1389 days respectively. The overall recurrence in the endoscopic group was 14.3% (n = 3) and in the surgical group it was 30.8% (n = 4).

At first follow up (6–12 months), two (9.5%) patients developed recurrent disease following their endoscopic resection (local recurrence) whilst only 1 (7.7%) had recurrence in the surgical group. Of the endoscopic recurrence, both cases had undergone cold snare polypectomy for removal of the duodenal lesion with an R1 resection. None of the cases having undergone advanced endoscopic resection techniques, such as EMR, ESD, FTRD have developed local recurrence. The local recurrence was managed with EMR and endoscopic surveillance.

The endoscopic and histological characteristics of the tumours which had disease recurrence are presented in Table 4.

Disease recurrences were observed in tumours which were larger than 10 mm, metastasized at the time of diagnosis, had high mitosis per high power field and high Ki67 index and had invasion beyond muscularis propria at the time of resection.

Discussion

ENETS, North American Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (NANETS) and other neuroendocrine societies recommend resection of non-metastatic duodenal NETs. The choice of resection method, whether it be surgery or endoscopy depends on a number of factors. For lesions > 20 mm there is a high risk of nodal involvement and so surgical resection is recommended. This was demonstrated in our cohort of patients. However, it is important to highlight that 85% of the surgically resected cases in our study had tumours > 10 mm and that careful staging investigations identified evidence of nodal involvement or unsuitability for endoscopic resection. It is important to ensure that endoscopic assessment of the lesion is carried out to assess characteristics concerning for invasion or unsuitable for endoscopic resection and such an assessment is performed as part of the staging process. The endoscopic features, that would be a concern for deep invasion, include: a Paris IIa + c morphology, central ulceration and convergence of folds, see Fig. 1. EUS is important for lesion characterisation and size. EUS will be able to determine if there is invasion to the muscle layer, any concerning nodal disease and accurate sizing of lesion. If there are no adverse findings and the staging scans have not demonstrated locally advanced disease, then resection can be considered. The choice of optimal resection techniques is unclear; there have been advances in terms of full thickness resection devices and modified EMR technique. The endoscopic expertise is important and having support from hepatobiliary and pancreatic services (in case of a complication) should be present. In our study, those who underwent endoscopic resection had tumour size of < 15 mm without any evidence of nodal involvement on cross sectional or functional imaging. A considerable proportion of tumours were found incidentally in those who underwent gastroscopy for other reasons hence did not have EUS. Further, our study dates back to 2006 where EUS service was not well established.

This study has shown that with endoscopic expertise and careful patient selection, endoscopic resection can be performed safely for duodenal NETs. Whilst the reported incidence of perforation of significant endoscopic complications like haemorrhage is up to 10%, in our series this was much lower. Furthermore, a macroscopic clear resection can be achieved in all cases. The significance of an R1 resection is somewhat unclear with these small lesions. We report three cases of recurrence, however, on review of these cases none had EUS assessment prior to the endoscopic resection. Two of these three patients had polypectomy and the diagnosis of dNET was incidental on histology.

There are several limitations which could have influenced the outcome of this study. Firstly, it is a single centre retrospective study with relatively small sample size. Considerable proportion of the study population was referred from local centres. Secondly, the endoscopic resection methods were not randomised and chosen in line with the local expertise. These could have posed selection bias and affected the generalizability of the findings. However, since duodenal NETs are relatively rare, our study findings still provide pertinent real- world data.

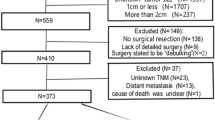

In conclusion, duodenal NETs are uncommon findings at endoscopy. When diagnosed, careful work up including histological grade, stage of tumour and suitability for endoscopic resection should be performed prior to determining resection modality. See Fig. 3. If adverse endoscopic or EUS findings, then surgery should be considered in appropriate patients. The optimal resection technique is yet to be defined, however, modified EMR, ESD and FTRD all can be performed safely by an experienced endoscopists. These resections should be performed in centres with access to HPB services. Further, prospective multicentre studies would be helpful to determine disease related mortality for patient undergoing conservative management and also to determine if an R1 resection impacts on recurrence and survival.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

Fitzgerald, T. L., Dennis, S. O., Kachare, S. D., Vohra, N. A. & Zervos, E. E. Increasing incidence of duodenal neuroendocrine tumors: incidental discovery of indolent disease? Surgery 158 (2), 466–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SURG.2015.03.042 (2015).

O’connor, J. M. & Bestani, M. A. R. M. I. S. S. O. L. L. E. F. Observational study of patients with gastroenteropancreatic and bronchial neuroendocrine tumors in argentina: results from the large database of a multidisciplinary group clinical multicenter study. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2 (5), 673–684. https://doi.org/10.3892/MCO.2014.332 (2014).

Dasari, A. et al. Trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the united States. JAMA Oncol. 3 (10), 1335–1342. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAONCOL.2017.0589 (2017).

Shroff, S. R. et al. Efficacy of endoscopic mucosal resection for management of small duodenal neuroendocrine tumors. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc Percutan Tech. 25 (5), e134–e139. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLE.0000000000000192 (2015).

Nabi, Z., Lakhtakia, S. & Reddy, D. N. Current status of the role of endoscopy in evaluation and management of Gastrointestinal and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 42 (2), 158–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12664-023-01362-8 (2023).

Rossi, R. E. et al. Risk of preoperative understaging of duodenal neuroendocrine neoplasms: a plea for caution in the treatment strategy. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 44 (10), 2227–2234. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40618-021-01528-1 (2021).

Massironi, S. et al. Heterogeneity of duodenal neuroendocrine tumors: an Italian Multi-center experience. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 25 (11), 3200–3206. https://doi.org/10.1245/S10434-018-6673-5 (2018).

Sundin, A. et al. ENETS consensus guidelines for the standards of care in neuroendocrine tumors: radiological examinations. Neuroendocrinology 90 (2), 167–183. https://doi.org/10.1159/000184855 (2009).

Pasquali, C. et al. Neuroendocrine tumor imaging: can 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography detect tumors with poor prognosis and aggressive behavior? World J. Surg. 22 (6), 588–592. https://doi.org/10.1007/S002689900439 (1998).

Sundin, A. Radiological and nuclear medicine imaging of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 26 (6), 803–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BPG.2012.12.004 (2012).

Varas, M. J. et al. Usefulness of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) for selecting carcinoid tumors as candidates to endoscopic resection. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 102 (10). https://doi.org/10.4321/S1130-01082010001000002 (2010).

Magi, L. et al. Multidisciplinary management of neuroendocrine neoplasia: A Real-World experience from a referral center. J. Clin. Med. 8 (6), 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM8060910 (2019).

Kunz, P. L. et al. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas 42 (4), 557–577. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0B013E31828E34A4 (2013).

Panzuto, F. et al. European neuroendocrine tumor society (ENETS) 2023 guidance paper for gastroduodenal neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) G1–G3. J. Neuroendocrinol. 35 (8), e13306. https://doi.org/10.1111/JNE.13306 (2023).

Panzuto, F. et al. Gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasia: the rules for non-operative management. Surg. Oncol. 35, 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2020.08.015 (2020).

Panzuto, F. et al. Endoscopic management of gastric, duodenal and rectal nets: position paper from the Italian association for neuroendocrine tumors (Itanet), Italian society of gastroenterology (SIGE), Italian society of digestive endoscopy (SIED). Dig. Liver Disease. 56 (4), 589–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2023.12.015 (2024).

Rossi, R. E. et al. Endoscopic Resection for Duodenal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms between 10 and 20 mm—a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 13 (5). https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM13051466 (2024).

Dell’Unto, E. et al. Clinical outcome of patients with gastric, duodenal, or rectal neuroendocrine tumors after incomplete endoscopic resection. J. Clin. Med. 13 (9). https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM13092535 (2024).

Hoteya, S. et al. Delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for non-ampullary superficial duodenal neoplasias might be prevented by prophylactic endoscopic closure: analysis of risk factors. Dig. Endosc. 27 (3), 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/DEN.12377 (2015).

Matsumoto, S., Miyatani, H. & Yoshida, Y. Future directions of duodenal endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 7 (4), 389. https://doi.org/10.4253/WJGE.V7.I4.389 (2015).

Kim, G. H. et al. Endoscopic resection for duodenal carcinoid tumors: a multicenter, retrospective study. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 29 (2), 318–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/JGH.12390 (2014).

Yi, K. et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic resection for duodenal neuroendocrine tumors. Scientific Reports 13 (1), 1–7. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45243-8

Chen, X. et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors: a 10-year data analysis of Northern China. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 54 (3), 384–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2019.1588367 (2019).

Nabi, Z. et al. Outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection in duodenal neuroendocrine tumors. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 26 (1), 275–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11605-021-05133-8 (2022).

Nishio, M. et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for non-ampullary duodenal neuroendocrine tumors. Ann. Gastroenterol. 33 (3), 265. https://doi.org/10.20524/AOG.2020.0477 (2020).

Esposito, G., Dell’Unto, E., Ligato, I., Marasco, M. & Panzuto, F. The meaning of R1 resection after endoscopic removal of gastric, duodenal and rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17 (8), 785–793. https://doi.org/10.1080/17474124.2023.2242261 (2023).

STROBE - Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology. Accessed May 10. https://www.strobe-statement.org/ (2024).

Bosman, F. T., Carneiro, F., Hruban, R. H. & Theise, N. D. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System (IARC, 2010).

Nagtegaal, I. D. et al. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology 76 (2), 182–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/HIS.13975 (2020).

R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Accessed April 28, https://www.r-project.org/ (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SC- data collection, data analysis and manuscript drafting, ST & RS- intellectual content, manuscript conceptualisation and manuscript editing. BH, AH, SG, AE, DR & JR – proof reading and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chandrapalan, S., Thrumurthy, S.G., Hayee, B. et al. Non-ampullary duodenal neuroendocrine tumours – a tertiary referral centre experience. Sci Rep 15, 34805 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19088-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19088-2